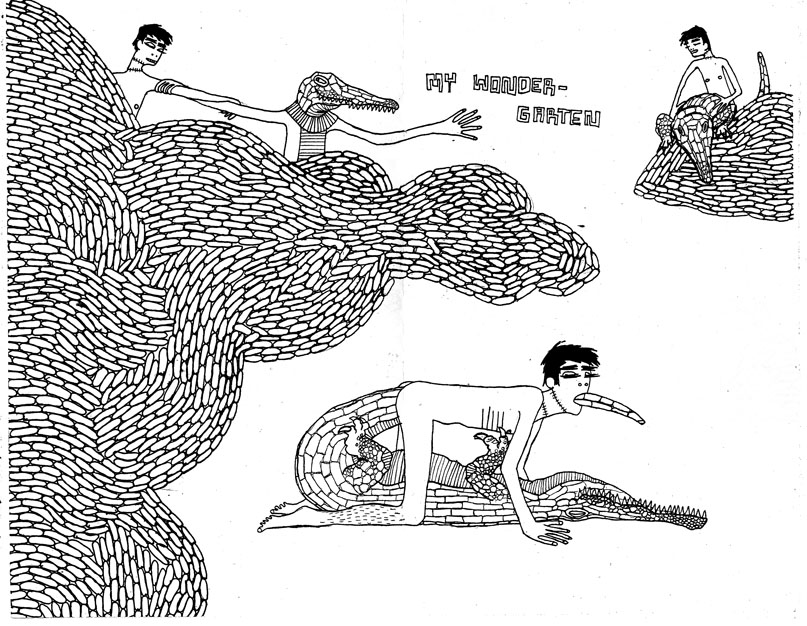

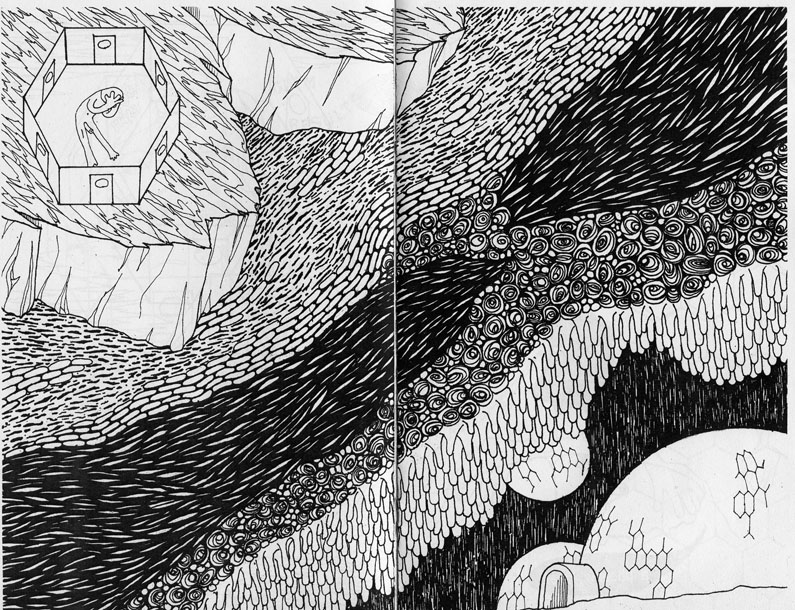

This is a work of pornography — not erotica — which also presents itself as a work of art. The graphical style is gorgeous and distinctive, the characters have individual personalities, and their relationships are respectfully and realistically explored in a way designed to appeal to women as well as men. The sex is violent, complicated, straight, gay, sadistic, very occasionally vanilla, and woven seamlessly into the storyline. I’m talking, of course, about Michael Manning’s *Spidergarden* series.

All right, it’s my little joke —I’m reviewing *Lost Girls,* just like everybody else. But one of the things that has annoyed me about the hype surrounding Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie’s book is the suggestion — promulgated by both authors and reviewers — that our culture is somehow starved for aesthetically pleasing, intellectually serious stroke material. Granted, there is a lot of crappy porn out there — but then, there is an almost unlimited quantity of *every* kind of porn out there. Underage porn? Sure. Porn with people dressed up in bunny suits? Check. Porn created by surprisingly clever people with humor, insight, wit and taste? Yes, indeed, grasshopper, for the Internet is vast, and most of it is devoted to smut. (As just one example, check out EyeofSerpent.) Even the use of pre-existing characters in compromising positions has become common — though, to be fair, slash fiction was a lot less high-profile when Moore and Gebbie first decided to, er, fool around with Wendy, Dorothy, and Alice 15 years ago.

Don’t get me wrong. I liked a lot of things about Lost Girls, even if it doesn’t exactly reinvent porn as we know it. It’s an ambitious and often bizarre undertaking, produced with obvious care. Moore’s decision to refer to it as pornography rather than erotica is admirable, and it is refreshing to see a book with this kind of aesthetic cache and marketing budget present itself so directly as an aid to orgasm, complete with contortionist sex positions, multiple partners, full-frontal everything, and even the occasional gratuitous slurping. In that vein, and purely as porn, it worked for me in the utilitarian way that such things do — there were scenes I found stimulating, they occurred with relative frequency, and the action that happened in the intervals wasn’t so off-putting that it killed the mood. I found the adult Wendy’s progress from buttoned-up, repressed Victorian housefrau to insatiable, big-bosomed tart particularly scorching. (Which means, I suppose, that, like Alan Moore, I enjoy the idea of fucking with the bourgeoisie.)

Despite its pleasures, though, there are some serious problems with the book. Moore and Gebbie clearly have an encyclopedic knowledge of Edwardian smut, but they have some trouble translating that into formal mastery. Gebbie’s artwork is hard to evaluate in the black-and-white photocopies we were sent for review, but the color panels I have seen are underwhelming. I admire her ambition, and I’m all for ravishing confectionary art, but Gebbie just doesn’t have the chops to pull it off. Her drafting isn’t strong enough to render anatomy convincingly, nor is it stylized enough to make up for the deficiency. Her color sense is erratic — some of the panels really work, but others are garish and even ugly. Her designs and layouts are okay, but hardly arresting. When Moore’s script calls for her to mimic the styles of artists like Aubrey Beardsley or John Teniel, her limitations become painfully obvious.

Like the art, the plot and writing both creak audibly. Moore has always been a heavy-handed writer, but in books like Halo Jones and Watchmen, he had such a thorough grasp on the genre material that it didn’t matter. At his best, even his clumsiness takes on meaning, irony, and resonance — the pirate sequence in Watchman, for example, is both ridiculously over the top and cool as hell, just like the pulp masterpieces it draws on.

There are great moments in Lost Girls too: I love the scene where Wendy, says goodbye to her husband from an upper-story window; he thinks she’s wailing in despair at his departure, when actually a bellhop is fucking her from behind. In general, though, throughout the book, Moore seems ever so slightly — well, lost. The idea of sexualizing famous children’s stories is a good one: I certainly found the transformations in the Alice tales weirdly erotic when I was a kid. Moore’s follow-through, however, is only sporadically successful. The Jabberwocky as a giant penis is funny — but it’s ruined when Moore has to tell us that it’s going to “jab” Alice. Dorothy masturbating while the tornado hits is okay; the labored metaphors which transform her subsequent lovers into the scarecrow, lion, and tin woodsman, on the other hand, wander dangerously close to the earnest pretension of literary fiction. In fact, much of Dorothy’s dialogue sounds like it was written in a college creative writing workshop by a Reynolds Price wannabe. One colorful, earthy metaphor per page is plenty, thank you very much.

Moore also has trouble with another of the goals he and Gebbie set for themselves; that is, creating pornography which will appeal to both genders. Women like all different kinds of porn, just as men do, of course, and I’m certain that there are many women besides Gebbie who will get off on Lost Girls. But there is, in fact, a lot of porn (not erotica, please note) written by women, for women out there, and it has tropes which distinguish it pretty clearly from porn designed for men only. Lost Girls does make some effort to incorporate a few of these: for instance, there is some male/male sex, which (as yaoi teaches) many heterosexual women like. But it’s not very central to the action; certainly it’s much less prominent than female-female sex, which (as most all porn teaches) heterosexual men like. Gebbie’s lacy, pastel artwork is very femme and may well entice some female readers, as may the fact that the protagonists are drawn to look like people, rather than blow-up dolls or supermodels.

But in all porn that has successfully connected with a large female audience, there is one common ingredient which is conspicuously absent from Lost Girls: romance. The possibility of love is only even hinted at a couple of times, and then it’s quickly dropped in the interest of further zipless fucks. Dorothy, Wendy, and Alice may like and care for each other, but they’re not “in love” with each other — they’re friends with benefits, which is to say they all behave like stereotypical male fantasies, not like stereotypical female ones. In Lost Girls, sex is about getting off, not about a particular partner — there’s no jealousy, not a whole lot of idealization, and almost no unrequited anything for even a panel. As a result, the fulfillment of every desire — for a stranger, for a friend, for a mentor, even for a father — feels more or less the same as the fulfillment of every other desire. That’s not the case in romance novels (which can be extremely explicit); it’s not the case in yaoi, or in slash fiction, or in virtually any other subgenre of porn that targets women. It’s consistent enough that I’m willing to go out on a limb and state in print that I am sure that Michael Manning’s hardcore fetish comics — which are all about relationships, relationships, relationships — have a significant female readership. (I do have some anecdotal evidence to back this up; my wife is a big Michael Manning fan.)

A lot of porn for guys is struttingly, or gleefully, or brutally loveless, without any aesthetic disjunction. But in Lost Girls the lack of love creates a sense of strain, and is responsible, I think, for the comics most noticeable and surprising failure, given its source material — a lack of magic. Moore and Gebbie try diligently to suffuse their world with a mystical significance, where bodies and identities fuse and flow. But all of their efforts — from the full-page fantasy money-shots to the game of dress-up the protagonists play at the end — seem didactic and forced. Again, a comparison with Michael Manning is instructive: in Manning’s work, characters change into furniture or animals, change loyalties, change genders, change personalities, duplicate themselves and lose themselves in a seamless erotic blur. Shojo manga too (though often less sexually explicit) projects a sense of trembling possibilities, as if every character is constantly on the verge of dissolving in a wave of longing and desire, It’s romance, of course, with its destruction of proportions and its vertiginous assault on the self, which drives the femme polymorphism of both Manning and shojo; and it’s the absence of romance which makes Lost Girls so frustratingly literal. With love, the most mundane incident can be charged with meaning and pleasure; without it, even meaning and pleasure lead only to a mundane contemplation of genitalia.

With its insistent cultivation of a female aesthetic, the decision to leave romance out of Lost Girls altogether seems strange. Even 15 years ago, before yaoi was around to show the way, a dollop of romance would have seemed a natural solution to the problem of creating artistic porn for all genders. Peter Pan, especially, is at least as much about repressed romance as it is about repressed sexuality — and Moore has said that he’d been turning over the idea of a pornographic Wendy long before he contemplated adding Dorothy and Alice. We know, too, from the rest of his oeuvre that Moore can do romance if he wants — Abby and Swamp Thing remain one of the most affecting couples in the history of mainstream comics, as far as I’m concerned.

The difficulty seems to be that Moore has very specific ideas about what pornography is and what it should do, and those, not coincidentally, happen to be precisely the things romance isn’t, and which it can’t accomplish. Romance is a genre devoted to a celebration of interconnection and complicated ties; it’s not just because he’s into bondage that one of Michael Manning’s books is titled In a Metal Web. For Moore, on the other hand, pornography is about splendid isolation. In a passage that is certainly intended to apply to Lost Girls itself, Moore has his lascivious hotel owner declare that, “Pornographies are the enchanted parklands where the most secret and vulnerable of our many selves can safely play…. They are the palaces of luxury that all the policies and armies of the outer world can never spoil, can never bring to rubble.” Sexual imagination, for Moore, is outside the demands and regulations of our government, our society, and even of ourselves. It is a means of experiencing freedom, both personal and political; an escape from entanglements.

Pornography does presuppose at least one connection, of course — that between the creator of the pornography and its consumer. This bond is to Lost Girls what love is to romance: the central, endlessly fascinating theme, both engine and end of the action. Instead of talking to a psychoanalyst, Dorothy, Alice and Wendy talk to each other, turning their traumatic Freudian relationships with various father-figures into deliberately arousing, pornographic narratives for the delectation of their friends — and, of course, for the reader as well. In repeated and insistent asides, each of the women talks about how turned on she is by the others’ narratives: Wendy, for example, admits that, “The more awful and dangerous these stories get, the more I want to play with myself.” This talking cure liberates not through simple revelation, but by turning an unmanageable network of relationships and desires into a single bond of functional arousal.

Freudian psychoanalysis is supposed to treat sexual neurosis and allow the patient to become reintegrated into society. Similarly, in Lost Girls pornography fixes various ailments, most involving a reluctance to have intercourse of one sort or another. There is a certain logic to this, anyway — if pornography is the cure, too little sex must be the disease. [Pre-Freudian therapists may even have agreed with Moore’s prescription. Hysteria, a commonly diagnosed ailment afflicting females in 19th century Europe, was often treated by bringing the patient to orgasm, sometimes through the use of vibrators, which were invented for the purpose.) Through profligate intercourse, Wendy ceases to be frigid. Alice is cured of her lesbianism, at least to the extent that she is now willing to have sex with men as well. Dorothy gets over her father fixation and talks, semi-seriously, about starting a family: I guess the fact that she’s the only one in the book who ever mentions birth control is supposed to suggest that, before dirty stories set her free, she was unreasonably worried about becoming pregnant.

If that’s a little snide — well, art as therapy has that effect on me. And while pornography as therapy at least has the benefit of novelty, I don’t see that it’s much different in kind. The tedious work of healing grinds on, and every encounter, whether with lover, enemy, wizard, elf, or double, is perceived through the monochrome fish-eye of self-actualization. As I noted above, sexualizing Oz, Wonderland, and Never-Never-Land doesn’t bother me, but turning these bizarre stories of nonsense and adventure into another pedestrian opportunity for personal growth is simply egregious. Moore has said he wanted to explore childhood sexuality without the hypocritical judgments usually attendant on such an exercise, but when it comes time to do so, what he comes up with is a bundle of trauma and some lame platitudes about embracing your inner lost girl.

Self-help manifestos are solipsistic by nature; nonetheless, they often try to present themselves as offering solutions to macrocosmic problems. After all, if everybody were happy within themselves, the world would be a better place, wouldn’t it? Moore buys the logic, anyway . Fucking and sucking in a heap of bodies and pleasures may seem politically innocuous — but Moore thinks otherwise, and to prove it he’s willing to drag an entire World War onto the scene. As German tanks roll towards the girls’ erotic idyll, the mere act of exchanging sexual fantasies and bodily fluids becomes pregnant with gynocentric political meaning. It’s brave little Eros vs. big bad Thanatos, and you’ll never look at an orgasm in quite the same way again.

I’m a good little liberal myself, and as such I’d much rather read Lost Girls than bomb Iraq. But to suggest that the first is some sort of meaningful resistance to the second seems kind of ridiculous. Sure, if you’re jerking off you’re not likely to be shooting anyone at the same time (though I guess you could if you were really determined). But you could say the same thing about shopping at Wal-Mart or taking a dump. So what?

Even if you want to see some sort of profound Jungian psycho-social link between creativity (sexual or otherwise) and violence, that link doesn’t have to be oppositional. Moore likes to quip that “War is a failure of imagination,” but why should we let imagination off the hook so easily? It’s hard to see, for example, how World War I could have happened without the help of a lot of violent fantasies filled with heroic nonsense — the exceedingly militaristic Peter Pan not least among them. Sexual imagination itself has led to preposterous amounts of violence, as Homer tells us. And you don’t have to be a fan of Andrea Dworkin to note that pornography may, occasionally, have something to do with the more unpleasant aspects of the sex industry.

Moore’s a thoughtful writer, and whatever his broader ideology, there are several instances in Lost Girls where porn and sexual imagination are shown to have a down side. Moore’s Peter Pan analogue, for example, grows from an over-sexed young urchin into an unpleasantly hardened male prostitute. And in Dorothy’s narrative, she realizes that her “horny little daydreams” about incest have ruined her step-mother’s life. This moment of clarity even contributes to Dorothy’s decision to stop fucking her father and leave home for Europe — though once there it doesn’t seem to have any moderating effect on her sex life.

Perhaps Moore’s most focused discussion of the damaging possibilities of erotic narratives involves Wendy. After fantasizing about sex with a dangerous child molester (Captain Hook), she semi-unconsciously seeks him out, and is almost killed as a result. In Faulkner’s novels, this sort of collaboration between victimizer and victim is a recurring theme, and is used to raise questions about how our dreams, identities, and destinies are attached to cultural expectations that we often can’t control, even when we recognize them. Led to the brink of such a depressing insight, Moore backpedals frantically, assuring us that Wendy’s real nemesis is not her fantasy per se, but rather her misguided feeling of responsibility for it. This is a big fat cop out, and the immediately following scene, wherein Wendy scares off the rapist by thrusting her cunt at him, was for me the least convincing in the whole book, and perhaps the only one that felt genuinely exploitative.

This failure of nerve is emblematic of the book as a whole. Moore and Gebbie make extravagant claims for pornography, but (or perhaps because?) they don’t really seem to have faith in the genre. Do readers really need to be constantly assured that they’re fighting the man and/or finding themselves in order for it to be okay to read a book with explicit sex in it? Porn has some ugly implications, but so do most genres and mediums, from the police state paranoia of superheroes, to the militarism of science-fiction, to the casual disregard of life in mystery novels, to, for that matter, the gushy disempowerment of romance. It would be a surprise if they didn’t, considering that all are part and parcel of a reality, which is, after all imperfect. Despite what some critics of porn might tell you, that’s not a reason to stop imagining (as if such a thing were possible), or to endorse censorship, or even to wallow in guilt. But it is something to think about before you ram a dildo up your ass and call it freedom.

A version of this essay first ran in The Comics Journal.

***************

Michael Manning is going to contribute to a symposium on the Gay Utopia which I am organizing. The symposium should be online in late January or early February. Other contributors will include Ursula K. Le Guin, Johnny Ryan, Dame Darcy, Neil Whitacre, Lilli Carré, Bert Stabler, and lots of other folks.