Last week I posted a lecture I gave on the importance of, and suppression of, male-male bonding and obsessions in comics. (Part One, Part Two.)

Some interesting comments and criticisms were brought up in the comments to those posts, particularly questions about Freud and why on earth I thought writing about this sort of thing was a good idea. I’m going to try to address some of those questions here. The result is going to be a bit rambling, but hopefully not completely uninteresting. So with that endorsement — off we go.

To do a quick recap of the argument: my basic point was that Western comics are obsessed with male-male relationships and heterosexual identity. That obsession is structured by homosexuality and the closet; maleness is always furtively in danger of splitting into a hypermasculinized overman (and hypermasculinity equates with gay) and into a feminized underman (which again, can be equated with gayness.) The fraught, agonized tension of of male-male desire becomes both the emotive force and the excuse for self-pity, and ultimately for violence, directed at women (who are despicably feminine and constantly interfering in all the male-male bonding) and towards other men (as objects of desire who can only be furtively embraced through physical chastisement.) Homophobia, misogyny, and violence, in other words, are motivated by a crisis in heterosexual male identity — a fear of an inescapable homosexuality, which becomes more inescapable the more (or less) male one becomes. I argued that this dynamic was present in classic super-hero comics like Superman, Batman, and Spider-man, and that it also existed in more well-respected indie comics like Cerebus and Jimmy Corrigan. Finally, I suggested that shojo manga dealt with gayness and emotional bonds in rather different ways. (Many of these ideas are adapted from Eve Sedgwick, who I’ll discuss some in this post as well.)

So that basically bring us up to date. The essay provoked a certain amount of skepticism, most notably from Pallas, a frequent commenter. He eventually asked a series of perceptive questions, among which were these:

What “erotic” means?

Is there such a thing as platonic friendship, or only “erotic” friendship?

Is the appreciation of a parent towards a child inherently “erotic”? (Hey, you brought up the Batman surrogate father examples, not me!)

Is it possible to appreciate aesthetic qualities without that appreciation being “erotic”?

I think, as Pallas suggests, these questions are central to my argument. They’re also, though, rather more broadly important; they’re essentially questions about how human beings interact with each other, whether as lovers or family or political actors.

I do have a couple answers for Pallas, I think. To start at the beginning:

“[Explain] What erotic means.}

I think “erotic” in this context means touched by, or having to do with, desire. So, for example, Clark Kent’s relationship with Superman can be seen as erotic, in that Superman can be seen fairly easily as a power fantasy; Clark desires to be Superman. That’s erotic — and since they’re both men, it can be read as homoerotic (and when I say “can be read” I mean it can be read that way not just by me but by Clark and to some extent by his creators.) Similarly, Lois desires to humiliate Clark — that’s erotic. Superman desires to humiliate Lois — again, that’s erotic — and, obviously, sado-masochistic. Or, as another for instance, Joker desires to destroy Batman; Jimmy Corrigan desires to become powerful like Superman; Cerebus desires to remain continent. Desires are erotic — and desire, in one form or another, exists in all human relationships. Thus, to answer Pallas’ second question, there is no clean “platonic” friendship, because all friendship is involved with desire.

This isn’t an original insight; most obviously, it’s associated with Freud, who argued that all human relationships, even the most sacrosanct (as, for example, those between mother and son) were charged with erotism and desire. He was roundly hooted for being a dirty old quack — and the scientific certainty he brings to his more outlandish theories is, I have to admit, kind of hard to take. When Freud insists “all human beings are bisexual…Psychoanalysis has established this fact as firmly as chemistry has established the presence of oxygen, hydrogen, carbon and other elements in all organic bodies,” it’s hard not to respond with a heartfelt, “You wish psychology was chemistry, Ziggy.”

I think the scientific foderol can obscure the fact, though, that when he argued that desire was central to human existence, Freud wasn’t just making shit up; he was restating a very old truth. Desire is, I think, a fairly good shorthand, secular definition of sin — a fairly important concept before the Enlightenment declared we were all clean, rational, democratic automatons. Freud was a benighted heir of the Enlightenment too, in his own way — thus his insistence that he was doing science instead of theology. But I think there’s a fairly strong argument to be made that he was a theologian in spite of himself; that, in focusing on desire and eroticism, he was simply (or not so simply) reintroducing sin as a motivating force in the affairs (variously defined) of human beings. Freud says this himself, when, for example, he points out that “prohibited impulses are present alike in the criminal and in the avenging community. In this, psycho-analysis is no more than confirming the habitual pronouncements of the pious; we are all miserable sinners.”

In short, the statement “all people are bisexual” is not a scientific truth. But that doesn’t make it false — and, in fact, since desire is part of all human relationships, I, at least, think that the statement “all people are bisexual” is, in fact, true.

So on to Pallas’ next question:

“Is the appreciation of a parent towards a child inherently “erotic”?”

…which lands us neatly in the Oedipal complex. Both Freud and Christianity, I believe, would answer Pallas’ question with an affirmative; the love of parent and child is erotic; it is charged with (selfish) desire, just like every other human relationship since the Fall.

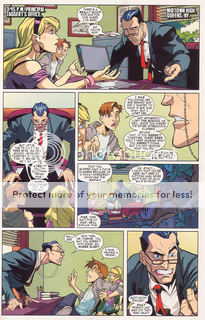

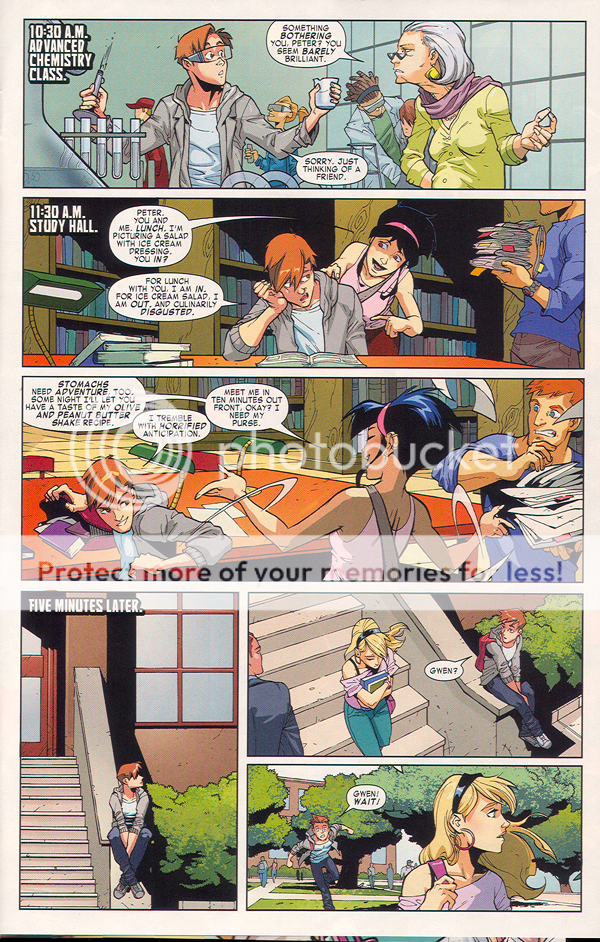

Freud would illustrate this with the Oedipus drama. But comics fans don’t need to go so far afield. Consider, for example, Spider-Man. Peter Parker is, like all super-heroes, surely a power fantasy; he’s a nerdy, nebbishy, feminized nothing who, though the miraculous oral intervention of an insect, is transformed into a paragon of masculinity, able to beat up professional wrestlers and earn money with a single upgraded chromosome. He changes, in short, from pitiful son to masterful father. In doing so, he also, inevitably, kills his own father (“Uncle” Ben)— and all the guilty emoting can’t quite erase the fact that the death of the father is not the end of the fantasy, but a continuation of it. To be a man is not just to have great power, but great responibility (for protecting the womenfolk, among other things); Peter can’t take his father’s place as protector of the weak (i.e., the women) if his father is still there.

(I googled Spider-Man and Oedipal conflict, incidentally,and was kind of startled not to immediately discover, like, 50 people making the same points above. Despite my failed googling, though, I am sure as sure can be that I am Not The First Person to Think of This — it’s pretty blatant after all. I’d imagine it at least occurred to Lee and Ditko themselves, for that matter.)

Or, to put it in less psychoanalytic and more Christian terms — children and parents envy and compete with each other; their love for each other is stained with desire. Even Peter’s noblest impulses (his desire to take responsibility and do good) are in part a selfish desire to be perceived as being as powerful as and as good as his father; to set himself up as an idol and take the place of God. (Probably the basic sin of the super-hero genre in general.)

Another way to look at this dynamic is through the work of Eve Sedgwick. I talked about Sedgwick a good bit in my original posts; she was a feminist and queer theorist, who (like a lot of feminist theorists) took Freud’s scientific/psychological ideas and recast them in a social/cultural context. In comments, Eric B (also known as “my brother”) provided a good summary:

Sedgwick’s point (derived partially from Claude Levi-Strauss’ account of kinship systems) is that we live in a patriarchal culture, where men have the power and are interested in maintaining that power. One of the ways in which this done is in the “trading” of women. Marriage serves a central function in cementing bonds between two families, consolidating patriarchal power, by joining two or more men in “homosocial” bonds. Women traditionally had no power in marriage (obviously this changes post 19th century) and so become “objects of exchange.” So…marriage itself is a weird structure–less about sex than about power and perpetuating bonds between families “ruled” by men. So…women become mediators of “relationships” between men. This reverses some old second-wave feminist accounts of “feminism is the theory, lesbianism is the practice.” Instead, its “patriarchy is the theory, homo- bonds is the practice.” This is how she links homophobia with misogyny. Women are treated as object in this model…but necessary objects. Without marriage (and therefore love and heterosexuality), you have no consolidation of power. Because of this “necessity” (just a structure–no “natural” reason why its necessary other than reproduction, which doesn’t require marriage, just sex)–homophobia develops as a part of patriarchal culture. Once marriage becomes important to power/economic structures, it must be maintained by powers-that-be and one of the ways that happens is a discouragement of same-sex relationships. So…misogyny and homophobia are linked…but they are also linked to homoeroticism (which isn’t always erotic, but often is), since the system requires (yes) the repression of homosexual sex, but also requires close bonds “between men.” It’s convincing to me more because of the links to Levi-Strauss account of kinship…an anthropological theory that is fairly widely accepted as helping to explain various “taboos” against certain kinds of marriage in a variety of different cultures/societies. I think there is some reliance on Freud, but the “repression” is less internal/psychological and more “socially necessary” to perpetuate a certain kind of culture. We don’t repress homosexual desires because of an overactive superego–but because we know society frowns on it and we can be gay-bashed for it, etc.

From Sedgwick’s perspective, then, the Oedipus story, and the Spider-Man origin, can be read (without too much of a shift from Freud’s version) as a fantasy, not about the infant’s love/hatred of his father, but about a man’s love/hatred for patriarchal power. Aunt May ends up as a chit in the power exchange between Uncle Ben and Peter. Peter’s feelings for his father — the patriarchal bonds of affection — are dangerous and inexpressible. Thus, Ben gets put out of the way, so that Peter can express his power fantasies (taking his father’s place in the patriarchy) through the safer medium of loving Aunt May on his dead father’s behalf. (Obviously, Peter isn’t marrying May — though it’s interesting that MJ is introduced to Peter by May. And it’s also interesting how important evil fathers are in those early stories; Norman Osborne, obviously, but also Doc Ock, who engages in an odd courtship with May.)

In any case, the Spider-Man story also shows pretty clearly how the Oedipal conflict, especially as interpreted by Sedgwick, ends up being structured by closeted homosexuality. Peter’s desire, his libido in Freud’s terms, is directed towards male power — the story is a power fantasy. As such, Peter is split in two; on the one hand, he’s the uber-father, with hyper-masculine powers, taking on the patriarchal father. On the other hand, he’s still a weak, helpless kid. This is what Sedgwick means, I think, when she talks about bifurcated identities — masculinity is always split like this, between absolute patriarchal power (which can perhaps be embodied momentarily, but is never absolutely attainable) and the individual self, (which always falls short of patriarchal ideals/responsibility/power.) It’s Spider-Man who takes the place of Uncle Ben…Spider-Man’s who signals that Peter has taken on the power and responsibility of the patriarch, or the father. But though he’s a man, Peter’s still also a frightened child.

So Peter is split. Oedipally, one part of him identifies with the powerless child, one part with the all-powerful (all-responsible) father. That split is charged with homoerotic desire; Peter desires the power of Spider-Man, which is also the power of his father, or of the patriarchy. I think too, contradictorily, Spider-Man desires the powerlessness of (ahem) Peter — the lack of responsibility. The Peter Parker/Spider-Man relationship is homoerotic — it’s about men’s desire for certain kinds of maleness.

At the same time, this relationship (and not coincidentally) is structured around the closet. The closet is about repressing male-male desires; presenting a united patriarchal front of power and responsibility to the world while concealing potentially dangerous emotions. The Spider-Man/Peter relationship is gay, and that gayness — or that feminization — has to be concealed. Spider-Man wears a mask because masculinity has no face; it’s an anonymous power. Beneath that mask is the face of someone who is not a man — a child — but the mask erases the child’s face. To become the patriarch is the desire and also the fear — the strength of the patriarch is also the strength of a monster: Thing, Hulk, Spider. The mingled desire and fear is why these relationships are agonized — to take on great power and great responsibility, you must be split. I discussed this in the context of the Friday the 13th films here.

All of which is to say, you can’t undermine masculinity by cutting it apart, or by pointing out that this or that person doesn’t measure up. Jason isn’t less of a man because he’s actually a child — or rather, he is less of a man, which is what masculinity is all about. Masculinity is always already bifurcated. On the one hand you have the Law — pitiless, perfect, unattainable. On the other hand, you have the implementer of the Law, the person the Law inhabits. That person is inevitably stunted, powerless, pitiful — feminized. The Law uses imperfect bodies, but that doesn’t make it less perfect. On the contrary, it merely emphasizes its disembodied perfection.

Again, you can see this in a Christian context as well — where too, obviously, father-son dynamics are fairly important. In some ways, Christianity is an effort to get out from under the Law; to replace the law with platonic love. Humans aren’t capable of platonic love, though. Instead, such love as humans are capable of (like Peter’s love for his father-figure) leads, via desire, back to a wish for power and thus to the law. That’s why Jesus has some harsh things to say about treating family bonds as more important than salvation, and why, ultimately, you need grace. (It’s interesting in this context that Spider-Man, Superman, et. al. were created by Jewish creators — “with great power comes great responsibility” is not exactly a Christian sentiment.)

Anyway, on to Pallas’ next:

“Is it possible to appreciate aesthetic qualities without that appreciation being “erotic”?”

If “erotic” is seen as meaning “desire”, I think the answer is no. Art is tied up in desire — the desire of the creators and the desire of the audience. This isn’t surpsing, since art is a human product meant to communicate with human beings,

The irony, of course, is that a lot of aesthetic criticism is tied to determining whether a given piece of art is free of desire, or pure, in particular ways. Art that seems clearly intended to make money, for example, is often denigrated as being inauthentic or impure. Similarly, art that caters to observers’ prurient interests (which is clearly erotic, in other words) is often downgraded.

Nonetheless, I don’t see how you separate aesthetics and desire. You identify with a character because you like something about him or her, and affections are (for humans) tied to desire. Even if you’re talking about abstractions, you’re talking about beauty, which is certainly linked to desire. There’s almost always, too, something compulsive about art — collecting, viewing, knowing, discussing — which seems inextricable from the mechanics of desire.

I think to me this is a big part of why art is worthwhile, or interesting. Desire — according to Christianity, according to Buddhism, according to Freud, according to innumerable pop songs — is at the heart of the human experience. If art isn’t erotic — if Spider-Man doesn’t satisfy and address desires — what would be the point, exactly?

Gene Philips correctly points out that there are types of desire other than homosexual or homosocial which can be dealt with through art, and, sure, I don’t have any problem with that (I talk at great length about bondage on this site for instance.) But relationships between men — tinged as all relationships are with desire — seem to me to be especially important, inasmuch as men, even now, play a disproportionate role in running the world.

___________

Update: More on this topic here.