Denny O’Neil, Mike Sekowsky, others

Diana Prince: Wonder Woman vol. 1-4

DC Comics

$19.99 each

Wonder Woman is virtually impossible to write well. The problem isn’t that the concept is dumb — on the contrary, the difficulty is that it’s not dumb enough. Most superheroes are artistic nonentities. Superman, Batman, Spider-Man, Wolverine — they’re defined by their powers and their backstory and maybe by one or two dabs of easily reproduced personality (Batman’s grim; Spider-Man’s down on his luck, Wolverine’s mean.) You can put them in different narratives because they aren’t integrated into any narrative. They aren’t the product of a coherent individual aesthetic in the first place, so imposing a different vision on them isn’t especially hard.

Wonder Woman’s different. Her creator, William Moulton Marston (with the help of his wife, Elizabeth Holloway Marston, and their lover, Olive Byrne) created the character to fulfill very specific political and sexual fantasies. Marston wanted to create a strong icon of femininity, so girls would be inspired to embrace feminine virtues, like love and… submissiveness. The result was Wonder Woman, a powerful heroine of justice who would preach about female empowerment in one panel, bash a bad guy in the second, and find herself trussed up like a turkey in the third. Harry G. Peter rendered Marston’s inspirational, fetishistic fantasies in one of the most distinctive styles of the golden age; his stiff figures, active lines, frilly imagery, and distinctive stylization gave Wonder Woman an outsider-art look somewhere between Fletcher Hanks and Henry Darger.

Together Moulton and Peter created a comic that had self-conscious ideological and aesthetic content. They set out, quite deliberately, to reconcile and explore binaries involving fetish and feminism, submission and strength, peace and violence, masculinity and femininity. Those contradictions, and the passion with which they were handled, give the early Wonder Woman stories an energetic, absurd sublimity like very little else in super-hero comics. But those same factors have made it extremely difficult for anyone else to use the character. Just as the most obvious example: how do you present Wonder Woman as an icon of strong womanhood when her costume is a ridiculous swim suit tricked out with fairly explicit bondage iconography (the rope, the metal bracelets)? Or, as another for instance, if Wonder Woman’s mission is supposed to be to bring peace and love to man’s world, how do you make that work with the fact that she spends most of her time hitting people? Moulton had specific answers to these questions because he was a crank and, I would contend, because he was a great artist. But if you’re not both a crank and a great artist, and you try to write Wonder Woman, you’re pretty much screwed. Which is why, while lots of people have written great Batman stories or Superman stories, I have yet to see a great Wonder Woman story written by anyone other than William Moulton Marston.

The one possible exception to that is “Wonder Woman’s Rival,” by Denny O’Neil and Mike Sekowsky. Initially published in Wonder Woman #178 way back in 1968, it’s the first story O’Neil and Sekowsky worked on, and thus the first entry in DC’s four volume “Diana Prince: Wonder Woman” reprint series.

Those four volumes are, by the by, utterly lacking in any contextual material; there’s no introduction, no commentary, no nothing. But, from what I’ve been able to determine from other sources, it seems that in the late ‘60s Wonder Woman was not selling especially well. DC was therefore open to letting Mike Sekowsky, the new editor and artist on the title, take some chances with the character. As a result, O’Neil and Sekowsky clearly feel liberated from any need to treat Wonder Woman with reverence or even respect, and the result is exhilarating. O’Neil turns in a script which is positively mean-spirited in its desecration of the Wonder Woman mythology. Steve Trevor, upright military man, is portrayed as a slimy, brutish, insecure Neanderthal. One particularly ludicrous scene shows him adopting hippie lingo to pick up some anonymous and much younger girl. Later, when he’s arrested on false murder charges, he behaves like a whiny baby-man, sneering at Wonder Woman when she, obviously heart-broken, is forced to testify against him. Meanwhile, Wonder Woman herself is depicted as deeply, weirdly insecure; “I’m not a woman, but a freak,” she cries after Steve has rejected her.

This is the last thing Moulton would have had the character say, obviously; for him, Wonder Woman was a paragon, not an aberration. But I think the outburst pretty clearly captures O’Neil and Sekowsky’s position; they want nothing to do with this nightmarishly outré heroine, nor with her ridiculous costume, nor with her unworkable mythos. Instead, they want to groove, baby. In an antithesis to Wonder Woman’s usual World War II honor-and-military associations, O’Neil sends the plot cavorting through hippie hang-outs, and sprinkles it with wannabe up-to-the-minute patois like “the fuzz frowns on chicks cruising in this pad solo” and “Yeah, man! We need some hens for a party!” Sekowsky, too, seems to be having the time of his life; the art is relentlessly modern retro-chic, with over-saturated psychedelic colors and bold, off-center constructivist layouts. The high-point is a full-page makeover sequence, where Diana Prince, preparing to infiltrate the burn-out underworld, goes on a shopping spree to get that happening look. Sekowsky uncorks everything he’s got: full-bore kaleidoscope effects, fabulous fonts, and dramatic patterned clothes. “Wow!” Diana declares when she’s done. “I…I’m gorgeous! I should have done this ages ago!” I guess, in O’Neil/Sekowsky’s world, Diana always secretly thought that the stars made her ass look big.

The comic is a mess, continuity-wise; Wonder Woman seems to completely forget that she even has a magic lasso when she’s interrogating people, for example. But that’s part of the charm; O’Neil and Sekowsky seem, not only not to care about the character, but to actually be contemptuous of her and her milieu. “Wonder Woman must change…!” Wonder Woman herself mutters at the end, and you get the sense that O’Neil and Sekowsky really believe it. They. Want. To. Do. Something. Else! They’re going to be modern, they’re going to be hip, they’re going to be different, and no stupid canon left to them by some decade-dead crank is going to stand in their way.

Alas, while a barbaric yawp is certainly good fun, it’s hard to build on it for the long term. O’Neil and Sekowsky are great when they’re gleefully leaping about on Marston’s corpse. As soon as they try to create something of their own, though, things quickly go to hell.

In issue #179, O’Neil, in the space of about three pages, strips Diana of her powers and sends Paradise Island into another dimension. Shortly thereafter, he shoots Steve Trevor, putting him safely out of the way in a hospital bed, where he is quickly and summarily forgotten (you never even learn if he recovers or not.) So far, so good. Wonder Woman is now Diana, a non-super civilian, struggling to adjust to her new humanity.

But then O’Neil introduces I Ching (groan) a blind (groan) martial arts master (groan) who trains Diana in his techniques while spouting (you guessed it) wise parables that appear to have been lifted directly from fortune cookies. Diana and her attendant master/racial stereotype then head off to battle Dr. Cyber, a typical evil genius whose sole distinguishing characteristic appears to be that she is a woman. Along the way, Diana encounters and semi-falls for a disreputable private detective named Tim who is just about as familiar as I Ching, though less viscerally offensive.

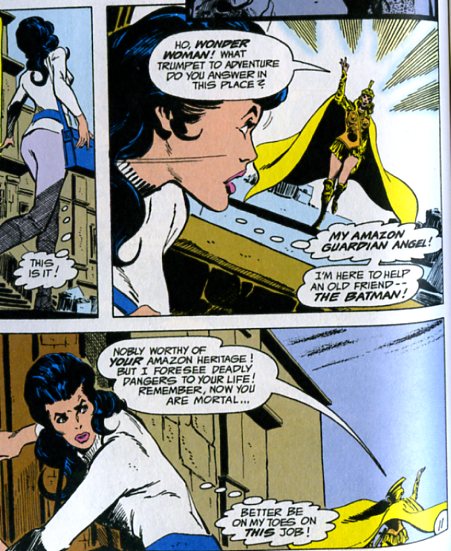

Sekowsky took over the writing chores himself with #182, zapping Wonder Woman back to Paradise Island for a sword-and-sandal battle royale. As the title staggers on, there are a few other one-shot exercises — a fantasy adventure, a ghost story, a couple of street-level helping-the-colorful-neighbors-with-their inner-city problems stories — interspersed with further campaigns against the inevitable Dr. Cyber. The different genres allow for some playful stories: one comic has an entertaining battle with a witch summoned by some neighborhood kids; another, by the irrepressible Bob Haney and Jim Aparo, features the bizarre appearance of a pint-sized “Amazon guardian angel” with whom Diana communes in a Gotham alley.

For the most part though, there’s little effort to experiment, either for thrills or laughs. Instead the four collected volumes read suspiciously like hack-work, created by folks who aren’t paying too much attention for an audience that they distantly hope isn’t paying too much attention either. Nobody, for example, ever bothers to give Diana a personality. Sekowsky supposedly based her wardrobe on that of Diana Riggs in The Avengers…but it wasn’t the clothes that made Mrs. Peel, but the wit and sophistication. Diana has neither of these, nor, indeed, any consistent character at all. There is one interesting issue where she’s presented as advocating torture; a vicious Diana Prince might have been kind of fun. But the trope is dropped, and Diana drifts back to the blandly heroic default.

Not that it’s all bad. A Rober Kanigher-penned Superman/Wonder Woman team-up, where Wonder Woman and Lois Lane vie for Superman’s love, has the requisite Superman-is-such-a-dick Silver Age appeal — plus you get to watch Supes and WW dance together at a space-age hippie shindig (Supes sets the floor on fire — darn super powers.) Sekowsky’s Wonder Woman/Batman team-up seems to reignite his creative juices somewhat, with Bruce Wayne alternately leering over Diana and worrying about his male ego (“I can’t let a woman and a blind man rescue me!”) Throughout the run, too, Sekowsky’s art remains enjoyable; he has a gift for pretty female faces, and the fact that Diana stays in civies gives him a chance to design a plethora of outfits for her. But even he never really regains the dynamism of that first issue, with its hippie coloring and in-your-face modernism.

Sekowsky eventually got moved off the title; Denny O’Neil came back for a bit, and finally sci-fi master Samuel R. Delaney showed up for two issues. In the first of these, Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser make a cameo because, apparently, Delaney wanted to prove that he could be boring with a whole range of other’s copyrighted properties. In the second story, Diana has her consciousness raised by a women’s lib group. I guess this last was somewhat controversial, and seeing Wonder Woman utter the words “for the most part, I don’t even like women!” is definitely jarring. But the whole thing’s so stupid anyway it’s hard to get too exercised about it. To say Delaney was phoning it in here is a disservice to telecommunications technology. The scripts read more like he leaned out the window and casually hawked them out between brushing his teeth and shaving.

The final story in volume 4 is the predictable reboot. Robert Kanigher, who’d written Wonder Woman stories through much of the fifties and sixties, came back to write another, while Don Heck supplied some strikingly awkward and ugly art. I Ching gets shot by a sniper, which is a lot less satisfying than you’d think it would be. Diana gets amnesia, Paradise Island is inexplicably back from its dimension- hopping, Wonder Woman regains her “special outfit.” It’s all so rote it’s hard to see why they even bothered; obviously continuity doesn’t really matter, so why even pretend to have a transition issue? Couldn’t you just put her back in the swimsuit without any explanation at all? Who would care?

I guess maybe somebody would have. Gloria Steinem cared that Wonder Woman had lost her powers, apparently; she’s supposed to have been the one responsible for getting DC to go back to the original, powered-up, scantily-clad version of the heroine. Soon thereafter WW was once more regularly appearing in tied-up bondage poses on her covers, something Sekowsky had kept to a minimum. A return to submissive cheesecake probably wasn’t exactly the outcome Steinem had hoped for, but you fool with Marston’s character at your own risk. O’Neil and Sekowsky had the right idea in trying to get as far from the original version as possible…even if, unfortunately, that was the only idea they had.

____________________

This essay first appeared in the Comics Journal.

Update: This is the latest in a series on post-Marston takes on Wonder Woman. The rest of the series can be read at our old blogspot address here.