In last week’s thread on definitions in comics, DerikB posed the question whether print advertisements count as comics. Sam Delany makes a convincing case that the question itself is impossible and probably shouldn’t even be asked, but he makes an exception for specific functional contexts where the project of definition works primarily to describe. On a case-by-case basis, examining whether or not a given definition describes a particular print advertisement (or anything else) can illuminate the strengths and weaknesses of the definition as well as the advertisement.

I responded to Derik’s comment by saying that I had a print advertisement I thought should count as comics. I called it a “found comic.” Wikipedia, not nearly as averse as Delany to defining things, observes that “the term found art…describes art created from the undisguised, but often modified, use of objects that are not normally considered art, often because they already have a non-art function.”

My usage recasts this definition for the present context: “found comics describes comics that emerge out of the juxtaposition of elements familiar from comics into material forms and contexts not normally considered comics, often because they have a non-comics function.”

Of course, the two definitions are not truly parallel: a definition of found comics that fully corresponded to found art would require that the elements of the comic be “readymade,” pulled from another context and different use, retaining the traces of that use, and making meaning through the resonance and/or contrast between the original and the artistic use. Found art depends upon that trace of the original context remaining, because the impact of found art is in the dissonant resonance between the original context and the art context.

Found art exposes the ways in which context – not form, not content, but the wall of the museum and the association with the artist – transforms a thing from an object into an art object. The sense of this depends on a cult of “the original” that is very powerful in visual fine art and less so in comics art.

Comics and literature are arts where reproductions retain the artistic value of the original (although not the historical value). They thus depend less on physical materiality and more on the creative generation and juxtaposition of ideas and images. Bricolage in comics, as in literature, pulls “objects” out of their original context and recasts them, and the act of recasting is so powerful that it transforms the meaning.

We don’t really have a concept of “found literature” because literature depends upon the context and presentation to a far smaller extent than visual art. The cut-ups of William Burroughs could be shoehorned into some definition of found literature – but it is essential to note that the conceptual signification of a cut-up novel is very different from that of found art. For this reason, although comics can certainly be made with readymade images using techniques of assemblage and collage and bricolage, I don’t see any particular analytic value in thinking of such comics as found comics.

Comics that can properly be called “found comics,” like found art, are objects whose very existence forces us to re-imagine the varied critical and cultural narratives that demarcate and generate the boundaries of what we think of when we think of comics. In that respect, they gesture toward critical positions and practices that are increasingly more and more inclusive of a broader artistic conversation, more engaged with liminal and marginal comics, more engaged with the normative critical practices of other art forms, while simultaneously allowing us, through comparison, to more finely tune our awareness and understanding of the comics at the center (a center that includes both conventionally defined art comics as well as “mainstream” comics, but not print ads).

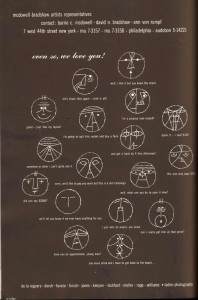

Here’s that advertisement I think qualifies as a found comic. (To read, click and zoom in.)

This advertisement appeared in the rear section of the 1950 New York Art Directors’ Annual of Advertising and Editorial Art. The last section of each year’s annual was a showcase for the trade: everything from ad agencies to typographers to paper companies took the opportunity to link their name and an impressive image in the consciousness of the most savvy and successful advertising and publishing professionals.

The agencies surely put their best foot forward in these ads, but as they were also selling a product, the work represented in that context necessarily reflected the company’s overall brand image. So to no small extent this ad represents the level of craft expected from a major advertising house, and it’s a pretty high level of craft. The faces are cubism in the guise of ‘50s flat-affect; the captions make the art director into a sort of “bogeyman wizard,” equal parts magic and intimidation. Representing the litany of criticisms and complaints the artist hears from the art director every day, each “panel” is so unique that it becomes easy for the viewer to imagine, to narrate, the day-to-day struggles of professional interaction and office life (this even without the suggestive resonance with Mad Men).

So this particular professional context certainly passes the criteria of “not usually thought of as comics.” I think I’m safe calling it “found.”

But does the ad fit any definition of comics previously advanced?

It would certainly be easy to think of it as a “single-panel cartoon.” But Scott McCloud tells us in Understanding Comics that single-panel cartoons don’t count as comics because they aren’t sequential. McCloud’s definition, building on Will Eisner’s simple “sequential art,” is “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer.” Does my “found comic” fit that?

I think I’d say the intended response is not so much aesthetic as meta-aesthetic, but that could arguably count. It’s definitely not in deliberate sequence. It does, however, in contrast to McCloud’s example of Family Circus, have some of the narratological elements usually associated with sequence.

RC Harvey gives us a slightly more fitting definition (copied from Wikipedia for expedience): “Comics consist of pictorial narratives or expositions in which words (often lettered into the picture area within speech balloons) usually contribute to the meaning of the pictures and vice versa.” But it still doesn’t quite work. In my advertisement, the narrative emerges as a resonance, but it’s not IN the comic, explicitly. There’s no direct reference to it. The advertisement is allusive rather than illustrative.

Both words and pictures contribute to this resonant allusive meaning, which is other than both. So the meaning is not cycling in between the words and the pictures in some interdependent “vice versa” relationship described above; instead it’s located in this third term (which I’m sure narratology has a word for that I don’t know). The text in the ad functions less to “contribute to the meaning of the pictures” as it does to anchor and restrict the meaning of the pictures, preventing a completely visceral resonance with the drawn faces –the simplistic “identification” with cartoons that McCloud talks about – and instead directing the reader to interpret the face, not only as a specific, identifiable expression but also as a moment in a narrative that the reader can fill in from general knowledge. These are clearly cartoons, but they are not “stripped down to their essential meaning” (McCloud, Understanding Comics, p. 30.)

I don’t think this is really a problem with my print ad being considered comics. I think it’s pretty obviously comics. I think this is just a problem with the definitions – they are not functional descriptions of this thing. Yet it’s not news that resonant, allusive meaning is part of comics, or that not all characterization in the cartoon form works via a very personal “identification” with an abstract face. Meaning in The Bun Field for example is located entirely in metaphor and resonance.

If you’re “in the know,” if you’re already a comics reader, it’s clear that Harvey’s definition refers to, well, things that meet Noah’s criteria of “things we all agree are comics.” But if you’d never seen a comic, what does that definition make you imagine? What do you imagine reading Scott McCloud’s definition – or at least, what would you imagine if you encountered the text pulled out of Understanding Comics without the pictures to clarify? Is it possible that comics can only be defined by showing a picture of them? And if that’s the case, why is McCloud’s definitional project so entirely unsatisfying?

Personally, I think that McCloud’s definition is perfectly suitable for describing the interior design of the hotel restaurant where I ate at on my last business trip:

Remember the definition was “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer.” I realize the obvious response is that the definition doesn’t fit because sculpture – in this case vases, mosaic, and a light differential – are not pictorial or images. But sculpture is visual art, so there is no real reason why someone who wasn’t already familiar with comics would immediately understand this distinction. And that objection becomes irrelevant once the design is photographed. Even if the design doesn’t strictly meet the definition, the photograph does.

Both the design and its photograph are sequential because of the light differential, getting brighter moving to the right in the vases and to the left on the blue lap. There are gutters and panels. You could argue that the sequence is not “deliberate” – but there’s also no way to determine conclusively that the effect wasn’t intentional. And it certainly provokes an aesthetic response.

I’m not implying that this hotel display is comics, or even found comics, necessarily. I feel certain that McCloud didn’t really intend for his definition to include it. Definitions that emphasize the print medium certainly exclude this design outright – but I nonetheless think it’s perfectly illustrative of the inadequacies of McCloud’s definition, and surely of many others.

To come up with a definition that actually fits my “found comic” advertisement, I have to go to the barest pared-down definition: Wikipedia’s page on comics uses the phrase “interdependence of image and text” to describe comics. (Their actual definition replays the “sequential art” line.) But honestly, that’s so vague that it’s not really functionally useful for understanding anything — it’s obvious just from looking at the page, so it doesn’t add any understanding to comics, and a illustrated newspaper article technically fits.

Yet, my advertisement really does look and feel like comics. I’m sure it’s some subset, like the single-panel cartoon, but it surely belongs in the comics universe. There’s definitely something else, something not captured in any of these definitions, that makes comics comics.

I love that ad — it really captures the visual style and sense of humor from that era.

It seems to me that your analogy to “found art” works because the answer to the question “What is a comic?” has been changing and expanding over time. The commercial artist who drew that piece in 1950 might well have been offended at the suggestion that he was working in the same medium as Joe Shuster or Mort Walker. His arty doodles reference Picasso and attempt to create a visual metaphor for the professional world of Madison Avenue. They aren’t crammed into sequential panels and tailored to provide campy entertainment for kids and working stiffs, which would likely have been the prevailing view of what “comics” were for a man in his field at that time.

At the same time, he would also be surprised to learn that anyone would be talking about it a year later. It was an inside joke for a trade publication. Purely ephemeral. Not to be taken seriously. Disposable in much the same way as comics were considered to be at the time.

But comics and visual culture have evolved in some very interesting ways over the past 60 years. So here we are.

I dunno… I tend to think Noah’s “Ed Meese” definition wins. I think public perception more than anything else is the deciding factor, and most people have a perception based upon 100 years of comics as a popular art. Anything remotely in that ballpark would pass the sniff test.

And I do think that most people would grok that ad as comics. It’s in the cartoon idiom, it does have a narrative (one that kind of sneaks up on you; a casual reader would be tickled by that), and it’s charming as all hell. Comics!

Most people are not going to split hairs with Scott McCloud over “Family Circus” not being comics (“It’s on the comics page, ain’t it?”), let alone read Thierry Groensteen. It’s not an argument that a lot of people (myself included, I admit) are really interested in having.

The side-effect of this is: if someone wants to claim something as comics, hey, no one’s going to stop you. I’ve been meaning to read that “Abstract Comics” book for a while now; I’m sure I will find stuff in it that doesn’t meet my personal traditional perception of “comics.” I doubt very much that I’m going to get personally upset about that and I’m likely to find something cool I wouldn’t have found on my own specifically because of that. (You can submit your photo for volume 2.) I’m personally not going to deny any work a spot at the definitional table. And I think a casual reader of that book would have the same attitude.

I’m not sure I really have a point here. But I’m also not sure I understand exactly who is so interested in nailing down a definition of comics (or any genre, really) and why.

–Chris K

(Footnote for clarity: I mention narrative as a criterion in my second paragraph; I know it’s not a necessity – McCloud sez so! – my point is that most people would see it as such)

Chris, you can’t imagine how thrilled it makes me that you just compared Noah to Ed Meese. (wink)

You’re right to pick up on the narrative stuff: I probably should have made that more prominent in this so it was more clearly a focus. I find it really curious how many people in comics see narrative as an absolute necessity. It’s like there’s this deep anxiety: “the text is what makes comics different from ordinary painting and drawing; without it they’d be plain old visual art, so they must tell stories.” And yet cartoonists are doing such interesting things graphically while the stories are often much less sophisticated: creators are less interested in the intricacies of prose, readers are less demanding, there’s just so little space for text in the books. But, then again, the narrative in this ad is pretty sophisticated…

Groensteen says comics are visual art, period, and I think he’s right. But I’m not convinced that he successfully pins down why, and I think it’s awful that so few people pay attention to the kinds of issues he raises, or talk about him!

It’ll probably be a months long project, and I might change my mind at some point in the process, but a lot of what’s at stake in the definitions for me is not “nailing down” some particular definition that works for all comics but in nailing down a “next step” after Groensteen. I hope at some point I’ll “get smart with the criticism” (to paraphrase Jerry Moriarty) enough that it becomes interesting to you!

Hi AJ: I wouldn’t be surprised at all if you’re right about the artist’s prejudices and influences; I really really REALLY want to find more out about the artist “Moller” who drew it, but so far no luck.

Pingback: Everyone’s A Critic | A roundup of comic book reviews and thinkpieces | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

In reply to A.J., I actually think it even more specifically references William Steig referencing Picasso and Klee. (The Steig of “All Embarrassed, “The Lonely Ones,” etc.)

Andrei and AJ: I’m going to dig through a couple of annuals; I know that many cartoonists did work in advertising (as well as other artists you may have heard of, like Andy Warhol). I’m curious now to see if I can locate anything by Steig, and even more curious whether artists with different backgrounds thought differently about ad work, if they were just paying the bills or if they saw any value in it. I’m wondering where it parallels and diverges from the ways artists working in comics thought about those gigs.

My quest for source materials on the history and culture of commercial art in this period is going slowly, so any and all recommendations are welcome.

Well, the connection to Klee’s faces is very direct:

http://www.westbynorthwest.org/spring00/pualklee.jpg

(compare with the “and get it back by 4” face)

And here is a Klee-influenced Steig drawing from “The Lonely Ones”:

http://www.michaelspornanimation.com/splog/wp-content/j/Lonelyones%201.jpg

Can’t find online a good drawing from “All Embarrassed,” but here is the cover of “Agony in the Kindergarten,” from 1950–which is, actually, even closer:

http://ic2.pbase.com/v3/89/475089/2/50050662.DSCN1279.jpg

I could even imagine “Moller” as a pseudonym Steig used for commercial work, though it’s probably just someone working under his influence.

Andrei! Those are fantastic; thanks so much.

Do you have any thoughts on how I might go about finding out who Moller was, Steig or otherwise? I’m not finding much secondary material on the commercial art business in this period, so I’m guessing I’ll have to dig in an archive, but I don’t have any idea how to track archival sources for commercial entities. I thought I’d check the ad archive at the NYPL, but otherwise I’m at a loss.

I see the Klee image is not opening… Anyway, here’s the search with which I found it:

http://images.google.com/images?q=klee+face&um=1&hl=en&safe=off&client=firefox-a&sa=N&rls=org.mozilla:en-US:official&tbs=isch:1

As for how to find any more info, I have no idea… I tried googling “Moller” and a variety of qualifiers that might get to “the” Moller, but nothing worked. I suppose the NYPL might work, but it would be a huge slog… And still it might not yield anything but other ads signed “Moller.”

Well, I *thought* I had left a reply… Let’s try again. I have no idea why the Klee image is not opening, but here is the search with which I found it:

http://images.google.com/images?q=klee+face&um=1&hl=en&safe=off&client=firefox-a&sa=N&rls=org.mozilla:en-US:official&tbs=isch:1

Caro–

this looks promising:

http://www.artnet.com/Artists/LotDetailPage.aspx?lot_id=2086D7A0DBF27F254C5B02EB917429BA

Oh, h*** yeah. VERY promising; it led me to this:

“In 1936, graphic designer Hans Moller and his wife, Helen, fled Hitler’s Germany for New York City. He easily found employment at an advertising agency but soon became fascinated by the Surrealist art of the New York galleries. In 1942, after several years of experimentation, Moller gave the first exhibition of what would be a career lasting nearly six decades.”

That’s gotta be him.

I can’t get that search result to come up when I put “Moller” into artnet, though. I’m not a subscriber; is there a more powerful search engine that I’m not accessing or do you just know tricks (i.e., do I need to pay, or practice)?

Smithsonian has a couple of great photographs of your Moller (who is hopefully also my Moller).

There are also some miscellaneous papers of his in the archive, so looks like there might be some clues just down the street…

That artnet link is the best Easter present ever, Andrei. :-)

And a search of google.de yields this obituary, which has birth info, some advertising career info, and more details on his fine art career.

This makes me suspicious, however, whether he actually drew my ad, because it implies he did not work in advertising after his first fine art exhibit in 1942. Could have been a one-off assignment, though, although it doesn’t sound like he needed the money.