In Caro’s recent post she argues that Asterios Polyp fails to deliver a kind of literary complexity.

The result is the reiteration – on the level of performance if not assertion – of a hierarchical division between “the literary” and the “graphical”: a dichotomy that is aggressive and dismissive in precisely the same way as Asterios’ treatment of Hana. It is completely uninformed about how literary fiction works. It creates a destructive incoherence at the center of the book.

I’ve probably bashed Asterios Polyp enough for one lifetime at this point. But I thought it might be interesting to look at a couple of examples of works that I think demonstrate the kind of literariness Caro is looking for.

I’ve been rereading Wallace Stevens recently, and I’m quite taken with this poem, the first in his first collection:

Earthy Anecdote

Every time the bucks went clattering

Over Oklahoma

A firecat bristled in the way.Wherever they went,

They went clattering,

Until they swerved

In a swift, circular line

To the right,

Because of the firecat.Or until they swerved

In a swift, circular line

To the left,

Because of the firecat.The bucks clattered.

The firecat went leaping,

To the right, to the left,

And

Bristled in the way.Later, the firecat closed his bright eyes

And slept.

As with a lot of Stevens’ poetry, nobody seems all that certain what the fuck this means. I’ve seen various efforts to parse it as some sort of allegory (the firecat means “change” was one particularly painful example.) But none of them are very convincing. Even the relation of title to poem seems maddeningly obscure. How is this earthy? Is there some sort of bizarre sexual double entendre known only to Stevens? That seems fairly unlikely — and yet, no other explanation presents itself.

The confusion here is, I think, on one hand simply a result of looking too deeply, or of coming at the poem from the wrong perspective. A lot of Stevens’ writing seems to me to be inspired not by abstruse epistemological theories or Romanticism, but by children’s poetry. “Earthy Anecdote” makes most sense if read not as allegory or complicated symbol, but as nonsense verse. Dr. Seuss’ battling tweetle beetles aren’t symbols of the futility of martial endeavor. They’re just goofy fun for kids. Similarly, the clattering bucks and the firecat are entertaining images. It’s fun to say “bucks went clattering over Oklahoma.” (Go ahead, try it. I’ll wait.)

At the same time…Stevens was also, and undoubtedly, inspired by abstruse epistemology and Romanticism. And he was writing verse for adults, not kids. Starting his first volume of poetry off with a bit of extravagant silliness is a fairly dramatic line in the sand — even if the line is curved. It’s a certain kind of statement; an elliptical declaration of love for the earthy, clattering bucks rushing about in glorious, purposeless panic — metaphors in frantic search for a meaning. In that vein, perhaps you can see the firecat as Stevens himself, leaping here and there to goad his images (and perhaps his readers) into a lather, before closing his bright eyes in self-satisfied pleasure. Or, alternately, Stevens might be the bucks, thrashing this way and that in an effort to avoid a meaning which is always leaping to thwart them — and which, in lazy triumph, curls around the poem at the end despite every horse’s best efforts.

None of these explanations are “right”, I don’t think. Rather, the point of the poem is the pleasurable possibilities of the point of the poem. That’s how the modernist puzzle works; the poem is playing with its own interpretation. Form and content (buck and firecat?) aren’t separated, or even separable; the content of the poem is its own metaphors. The reader doesn’t so much understand the poem, as shuttle about inside it. It’s a joke where the punchline is that the form of the joke is the punchline.

There are not a ton of comics that play these kinds of shell games with meaning, form, and content. But one example that does spring to mind for me is Yuichi Yokoyama’s Travel. In my review on Comixology I wrote:

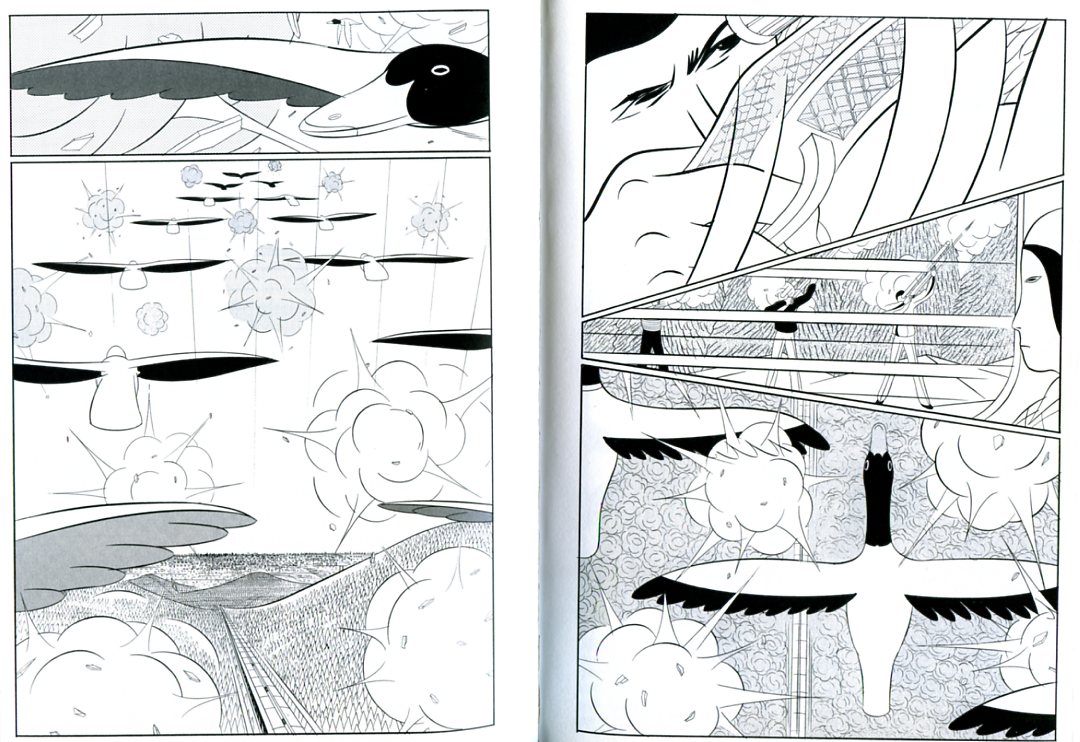

Yokoyama had wrong-footed me. I was looking for realism, and so I found the epistemological uncertainty frustrating. But the book isn’t realism — or not exactly. It’s pomo; Yokoyama’s tongue is in his cheek the entire time. Take the scene of ducks flying over the plane as hunters shoot at them. The footnote points out that the hunters all miss, and indeed, you can see the ducks traveling in a perfect V, not even disturbed by the shells exploding in pristine, regimented bursts all around them. The demands of narrative (somebody shoots, somebody hits) are sacrificed, with a wink, to the exigencies of layout. It’s as if the hunters and the ducks are not adversaries at all, but part of some single great mechanism, controlled by one guiding hand. As, of course, they are.

In Travel, as in Stevens, the sleight-of-hand manipulation of the tropes of the medium, the formal elements of the work, are themselves the content. As a result, modernist works like this are like two facing mirrors; absolutely flat surfaces leading into infinite depths.

I’m not saying that this is the only kind of worthwhile art by any means. I don’t want all art to be playful modernist puzzles anymore than I want all art to be slasher films or shojo. Still, Stevens and Yokoyama are great, and I wouldn’t at all mind seeing more comics that followed in their hoofprints.

The one other comic I think of immediately when this kind of conversation comes up is “Driven By Lemons”. It seemed like nobody wanted to talk about that book when it came out, though.

It’s not hard to rekate Stevens to art like Gauguin (exotic colors and peoples), or fiction like Kafka (inscrutable parables of the ancient modern unconscious), or music like Ives or Shostakovich (fluid but melodic), or philosophy like Heidegger or Deleuze (dissolving boundaries, heroic egoes, vibrant vitalism). But he’s just basically about the semiotic, the awesome power of the arbitrary framed by a vision of pastoral pantheism, the way that words clash together without the necessity of a narrative– except the ideological narrative implied in mythological motifs.

Hey Noah, great stuff — I love Wallace Stevens and really dig Yokoyama. What I’m not sure I buy is your assertion that this is merely post-modern formal equilibrism. Isn’t what both of them do merely what poetry and art have always done — suggest moods, places, emotions, etc. by way of their form, without pinning down specifics?

It’s hard to imagine Keats titling a poem in such an aggressively unhelpful way; it’s hard to imagine, say, Rackham providing deliberately obscurantist annotations to his pictures. The evocative use of form to suggest emotion is certainly of long pedigree; the self-conscious reinscription of the lack of specifics as a joke/evocative moment in its own right seems very modernist to me.

Absolutely. The form is highly spontaneous, and wedded to the supremely abstract subject matter, irregular decoration around a deliberately empty core, unfinished thoughts and hanging conclusions. Twentieth century post-metaphysical profundity to the max.

Hey, if you’re into Stevens, Matthias, we should do a Stevens roundtable! That would alienate our core audience….

That might be fun!

It would be fun. I kind of want to do one on Reinhold Niebuhr too…. We’ll see. Don’t want to presume on the patience of the comics fans too much….

——————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

As with a lot of Stevens’ poetry, nobody seems all that certain what the fuck this means. I’ve seen various efforts to parse it as some sort of allegory (the firecat means “change” was one particularly painful example.) But none of them are very convincing…

——————–

Humph! I dunno much about his work, but it sure seems to me that he’s describing a fire sweeping across the prairie, with the animals trying to avoid its changes of direction. Until the flames finally die down and “sleep.”

After writing the above, I tried a search to see if my assumption was on-target or not; among other suggested meanings, the entry at http://knitandcontemplation.typepad.com/dao_wallace_stevens/2004/09/earthy_anecdote.html ends with:

———————

Stevens’ daughter, Holly Stevens, writes about ‘Earthy Anecdote’ in her retrospective book on her father “Souvenirs and Prophecies”: “(quoting his letter home): ‘Thence I went through Nebraska and Iowa (which is a superb state) and on to Niagara Falls and to New York and home. The best thing I saw was a lightning storm on the prairie. I leaned out of the smoking-room window and watched the incessant forks darting down to the horizon. Now and then great clouds would flare and the ground would flash with yellow shadows.’ The geography he traversed put him near, if not in, Oklahoma and, in his reference to ‘a lightning storm,’ perhaps the background for ‘Earthy Anecdote’ where ‘Everytime the bucks went clattering/over Oklahoma/a firecat bristled in the way.’..

———————-

Cuteness alert — photos of Fire Cats! AKA, Red Pandas:

http://tomclarkblog.blogspot.com/2011/01/firecat-in-nature-theatre-wallace.html . Where it’s also put forth…

————————

…the mistress of the manor has suggested, with characteristic sensibleness, that Stevens may have been thinking about wild fires moving across the prairie, and thus using “firecat” metaphorically.

————————-

That’s a nice reading, and possibly an inspiration….but it doesn’t exactly explain the title, and doesn’t really explain the action of the poem…(for example, the lightning ceasing or fires ceasing doesn’t really work with a cat going to sleep — the cat is still there when it’s asleep, after all, but the fire is gone when it’s “asleep.”)

i agree with the MotM. you’ve been overthinking perhaps. fire is of the earth (hence ‘earthy’ anecdote), and preys on the bucks like a cat; he “closed his bright eyes” meaning the flame goes out, but the wildfire’s potential remains in the slumbering cat, a perennial condition of the prairie.