What if Ord Resurrected Jean Grey instead of Colossus? Written by Jim McCann, Art by David Yardin, Ibraim Roberson, and Kai Spannuth. February 2010 One-shot. (It contains two other stories, but I don’t care one way or another about them, so I’m leaving them out.)

I admit that I didn’t read the story about Ord resurrecting Colossus (whenever that was…), and I have only vague white-noise understanding of the main plot points here, but it didn’t matter. I’ve gotten a certain amount of flack for failing to understand continuity plot points in the past, and I maintained then and maintain now that if comics are to get new readers, they’re going to have to accept that some folks won’t have read all 80-gazillion crossover title storylines, and that a good, a strong comic will clue in new readers or find other ways to engage them besides the longer plot throughlines.

And this comic is a perfect example.

We start off with a lovely page explaining the set-up of the one-shot story. In our world (the main continuity world), Colossus was resurrected instead of Jean Grey, and he united the X-Men. In this alternate world, it works differently. Dun-dun-dun.

I’m going to mangle this, because I have bare-minimum knowledge, but it seems to be: The planet Breakworld has a prophecy about a world-destroying force tied to mutants. Sensibly, they’d rather not be destroyed, and this ends up in some sort of complex involvement with Jean Grey and Phoenix and the X-Men. And Emma Frost thinks that Jean Grey is going to kill the planet and–look, it’s all too complicated, I’m sorry. There’s a baddy named Cassandra who looks like one of those old pickleheadjar people, and a dude/lady named Ord with a white sausage wrapped around their head who they’re interrogating. Just go with it.

Let the plot flow about your heart like a river, it’s relaxing. Promise.

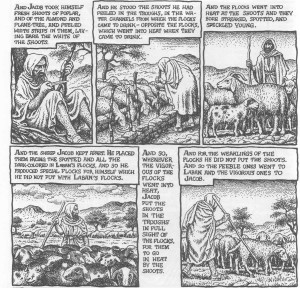

So, we’re following this inner X-Men fight. Look at this composition:

See how the colors shift from warm, muted tones to icy gray at the bottom? The figures are lovely, well drawn with interesting poses and good features, but it’s the colors that caught my attention.

While there is linework here, it’s in a very painterly style. The colors of the lines shift with the colors of the painting–in the top panel, the lines are soft, warm browns but at the bottom, there is cool gray and even white. Lovely stuff.

That’s a pretty obvious example, and is the one that first caught my eye, but as we move through the story there are other examples. Flashes of cool gray taking over everything, dark icy eyes turning into fiery hot flames when Phoenix starts possessing Emma. I wish I could scan the whole darn thing, but there’s those pesky copyright issues, and besides, I want everybody and their cousin to rush out and buy this thing. (Go, I shall wait right here until you’re done. Have it in hand? Good.)

So in the plot, Emma holds hands with three hot blonde schoolgirls in cute preppy schoolgirl skirts, as if this was a twisted porno. They all channel the Phoenix, and then the power turns the pretty girls into zombie looking corpses. At which point….

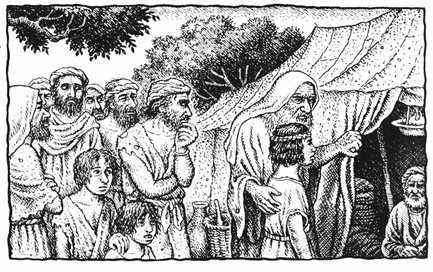

The girl heroine is awoken by her plucky dragon! And my heart soared. This is what comics is about folks. Awesome girl, plucky dragon, great art, cool things happening. Check out the more subtle color shifts in this one. We start with darkness, but it’s tinted with the warmth of the sky. The girl is soft brown and her dragon is soft red, and it’s all sweet and warmth, slowly awakening…and then, as they encounter the horror, the colors shift to pale grays. Neat!

The girl heroine is awoken by her plucky dragon! And my heart soared. This is what comics is about folks. Awesome girl, plucky dragon, great art, cool things happening. Check out the more subtle color shifts in this one. We start with darkness, but it’s tinted with the warmth of the sky. The girl is soft brown and her dragon is soft red, and it’s all sweet and warmth, slowly awakening…and then, as they encounter the horror, the colors shift to pale grays. Neat!

Also, check out the beautiful painted slouchy socks next to the harsh metal surfaces. Really, really well done, I thought.

So, this being a comic, Kitty runs to check out the problem, Jean Grey awakens, and there is a big battle with Emma Frost, who is possessed by the Phoenix. There’s some awesome shots of Jean and Emma fighting, and Jean’s pink power makes for a wonderfully feminine power touch to the fierceness and the battle. But Jean and Wolverine and the X-Men can’t fight her completely, and Kitty… Well, let me show you.

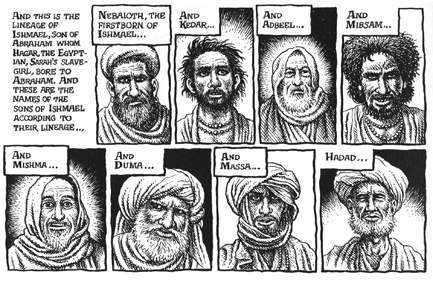

She rips out her heart.

It’s gorey and fierce and wonderful. I was talking a bit about the heroines of comics in my WonderWoman pants rant, and one of the problems I see is that the women aren’t allowed to be as fierce in their defense of worlds as I would like. Now, I’m not saying that, oh violence is hunky dorey per se, but I am glad to see that in this case, a young woman, with the help of her female mentor, did what needed doing to take out a planet-killing monster. This particular comic is a battle of females, and it was beautifully done. Kitty looks powerful and good, strong and young and feminine, saving the world.

There’s a kind of warmth and sweetness in the painting of Kitty.  Powerful, violent, but sweet and tough. The expression and curves reminds me of the best of the Pepper Project series.

Powerful, violent, but sweet and tough. The expression and curves reminds me of the best of the Pepper Project series.

Which means, naturally, that she dies. Freaking bad villains and their stupid power backlashes, dammit. (Since it’s the Phoenix that killed her, I’m just going to assume that she gets to come back. Don’t disabuse me of this notion, OK?) Anyway, the whole comic really has a lovely feel to it, a warmth and intensity that I deeply enjoyed. I’m sure that since it’s a painting style that it must have taken a gazillion hours to do, but I hope that more like these come out. I’d buy them in a heartbeat. Highly, highly recommended, even if you don’t know the plot.