Alan Choate left a long series of comments on Suat’s discussion of R. Crumb’s Genesis. Alan is actually going to post some additional thoughts on the blog here next week, so in preparation for that I thought I’d move his initial discussion into a post where it would be more easy to access.

The discussion of Genesis has turned into a kind of slow motion roundtable, so I thought I’d put it under one rubric. You can read all of Suat’s discussions and Alan’s (and maybe others if they pitch in!) Under the header Slow-Rolling Genesis.

So here are Alan Choate’s original comments.

_________________________________________

Hi, Suat. I want to answer your review at some length because I have a lot of problems with it. I see numerous errors, a casual reading of the book, and some shaky assumptions supporting the whole thing. You make a number of dismissive remarks in the review and the comments that strike me as haughty, unfair, and wildly off-base. The biggest problem is that you’re falling readily into a basic error for a critic: refusing to assess a work on its own terms.

I should add immediately that I have an indirect entanglement with this (as they say.) You mention my suggestion “…made in all seriousness” in the comments to Heer’s post that Robert Alter, in his review for the New Republic, “would feel threatened (the words used are ‘nervousness’ and ‘professional jealousy’) by Crumb’s awful biblical scholarship,“ calling it ”laughable if not symptomatic of a deranged comics provincialism.“ It’s not right for me to get after you for saying things I find arrogant without apologizing for that. ”Professional jealousy“ was way too strong, and I take it back.

What I said was that Alter seemed nervous about the use of his translation- he spoke of his ”entanglement“ in the project, and the man’s job is choosing words- and may have nursed what I did call a professional jealousy between one exegete and another. I found Alter gracious and full of biblical insights, saw that he made a good effort to engage Crumb, but my reason for saying that was that he treated the adaptation as a failure because it couldn’t be regarded as definitive. I thought he was basically telling us why we should still read the Bible (preferably with his notes), and didn’t seem to grasp that Crumb was suggesting possible interpretations in much the same way he did, though his commentary did have the advantage of being able to list several at once. I‘d never say ”Crumb’s awful biblical scholarship“ was threatening to him, rather the rampant popularity that defenders of the canon ascribe to comics, and the notion that youngsters who read it might assume they’d read Genesis itself because the comic book has every word.

I am honestly not bothered by being called a ”deranged provincial“- feel free to look at me that way- and I hope it will be apparent that my issue is with other things you’ve said. According to you, Crumb did not ”read closely and with an intent to understand,“ his adaptation was ”stripped of emotional and mental investment,“ it suffered from ”artistic lassitude“, ”awful biblical scholarship,“ and an ”almost anti-intellectual approach“. You even pull ”half-digested pabulum“ out of the Comics Journal grab-bag. (Could it also be pernicious, odious, fatuous, and supererogatory?) ”Those with a serious interest in the original text and the rich tradition of biblical illustration“ can only find the book a ”well-crafted curiosity,“ and it ”might be of greatest use to readers whose minds are in a more formative state.“

This is strong stuff. I want to examine it by looking at the same parts you do and I’ll try to build into an overall assessment of your approach. I hope to also answer not just your review but a certain strain of commentary I’ve seen about the book.

The creation and fall of man are ”the two most famous chapters in Genesis… these factors will make the ascertainment of the extent of Crumb’s achievements in The Book of Genesis that much easier.“

This convenience is significant. My unscholarly sense is that visual adaptations of Genesis tend to fall back on the Garden of Eden and the Flood, with the second rank including the Tower of Babel (one famous image), Sodom and Gomorrah (fiery rain and pillar of salt), the sacrifice of Isaac, and Jacob’s ladder. Creations have been done but seem a bit vague for most artists; I think I should be able to call a famous Cain and Abel to mind, but can’t. Much of Genesis, as with the rest of the Old Testament or Hebrew Bible, is unfamiliar in visual art or dramatization, and parts may never have been depicted. (Anybody can scrape up examples with an image search, but let’s play fair; you know what I mean.) Jesus and Mary have been the stars of Western art, and the Hebrew Bible is recalled in a sprinkling of highlights.

A comprehensive visual dramatization of Genesis is unprecedented. This is a major part of this project’s reason for being. As Crumb says, “they gloss over it. When you’re a kid, they don’t inform you that Lot has sex with his daughters. Or that Judah slept with his daughter-in-law. Those parts are just glossed over. In illustrating everything and every word, everything is brought equally to the surface. The stories about incest have the same importance as the more famous stories of Noah and the Flood or the Tower of Babel or Adam and Eve or whatever. I think that’s the most significant thing about making a comic book out of Genesis. Everything is illuminated.”

There are other virtues to the adaptation, which will hopefully emerge in my examination and will be discussed as I wrap up. But the glaring obviousness of this one makes me wonder how seriously you’re taking this when you say things like ”there seems little point in retreading ground your artistic betters have fully exploited half a millennium ago.“

Your choice to focus on the Garden of Eden is itself interesting, since it’s highly atypical. It is the only part shorn of costume, tools, man-made structures, and any human culture at all. The characters are ideal ”types“. Visually, the rest of the book is astonishing in its quotidian detail, and one can find new delights on any page even after multiple readings, but the relentlessly straight-on layouts and total commitment to a credible milieu for the patriarchs create a rigorous visual style that could be considered as much a demand on the audience as classic art-house cinema. You can dismiss it as boring (for devil’s advocacy, here’s Johnny Ryan), but there’s also a seriousness to it.

By contrast, the Garden of Eden scenes are playful and fanciful. You point out this lightness, comparing the moment when Adam and Eve cuddle next to God and the woodland creatures to Disney. And you’re not wrong. (Though this is right before a startling tonal and narrative shift when it to a different version of man’s creation, this one primal and stark, right on the same page- a bold feature that I’ve never seen in an adaptation.) But your handling suggests that the tone of these parts is consistent with the rest of the book. You even point to the Adam and Eve scenes to answer Ken Parille’s description of the book’s aesthetic, without any hint of their difference:

”Crumb’s illustrations assume a sort of perfection of human form and behavior as far as Adam and Eve are concerned. I presume that this is one example of the “beautiful” materiality of The Book of Genesis which Ken mentions in the excerpt above. There is certainly a degree of exaggeration and a filtering through the artist’s eye but this is not a particularly earthy version of Eden… There is very little of that grimy commonness which we see in the Gospel adaptations of Pasolini or Chester Brown.“

You write of Crumb’s drawing of the creation of Adam,

“His solution was not an uncommon one during the Italian Renaissance, here made fresh by showing the stages in this act, in particular the breath of life given to Adam (the word “breathed” or “blew” here suggesting the intimacy of a kiss). Crumb’s adaptation is also notable for showing Adam in his clay-like state, a reminder of the Egyptian (see The Hymn of Khnum and Hekat) and Mesopotamian (see Enki & Ninmah, and Bel) myths which carry the same motif.

“As articulated in his short commentary found at the end of The Book of Genesis, Crumb is particularly interested in these ancient tales of creation and periodically inserts them while neglecting to emphasize the many internal consistencies, dilemmas and word plays in the Biblical narrative. Thus, for example, the “dirt of the ground” is linked to pagan tradition and not to a play on the words “man” (adam) and “ground” (adama) where “man is related to the ‘ground’ by his very constitution (Genesis 3:19), making him perfectly suited for the task of working the ‘ground,’ which is required for cultivation…his origins also become his destiny” (Kenneth A. Matthews).“

Where do you see a pagan tradition being inserted? The text specifies that God blows life’s breath into the man’s nostrils. Adam’s constitution from the ground is vividly illustrated. It could be reminiscent of Mesopotamian or Egyptian motifs but Crumb never mentions this in his notes, and the Bible does say “the Lord formed the man from the dirt of the ground.” It’s not clear what suggests to you that the artist is unaware of the link between man and ground or his destiny to work it, or what kind of signal you were hoping Crumb would send.

But you miss the way Crumb does emphasize Adam’s name and connection to the ground after these three panels. You’re not much impressed with the high-volume dressing down Crumb has God give Adam and Eve: “The entirety of God’s judgments from Genesis 3:14 to 19 are depicted without comment or analysis. The artist’s hand here is as distant as a machine-operated drafting tool.” But surely you noticed God’s jabbing finger. He does it a lot in that scene. The action through the Creation has been led by what God does with his hands- always with open palms, arranging things, introducing people to each other and their habitat. The only time until now that he pointed was to identify the forbidden tree. The only other pointing was Adam’s, naming the animals. Now God points at him: “To Adam he said… Cursed be the ground because of you!… By the sweat of your brow you shall eat bread, till you return to the ground, for from there you were taken! For DUST you are, and to DUST you shall return!” (Crumb’s emphasis.)

It’s easy to miss, but until now Adam has been “the man.” This is where he is named- named earth, or dust. Crumb has associated pointing with forbidding, punishment, and naming. For the expulsion from the Garden, God sends “him”- not “them“- “forth to till the ground from which he had been taken,” and Adam is shown carrying a tool. They’re in new, uncomfortable clothes, distressed, and getting ready for a life of work. On the next page we meet Cain, “a tiller of the soil”- who is constantly shown flushed and sweating. Crumb is recalling God’s line that “by the sweat of your brow you shall eat bread.” Cain’s offering to God is “from the fruit of the soil”- unspecific, but Crumb shows it as a basket of grain. (Jacob is also shown pounding down what might be grain or flour with his mother- is Crumb using Esau’s skill in hunting to set up a parallel?) The meaning of all this would take us into Biblical analysis, but Crumb has helped guide us to these issues.

“The stated “literalness” of Crumb’s adaptation as well as its generally bland imagery will lull many readers into the false impression that Genesis intends a deep consideration of centuries old biblical scholarship. It doesn’t, an important point which I will address in more detail later.“

It gives me the impression that he intended to consider the Bible. I don’t see how later scholarship is suggested, and surely Crumb wasn’t surprised to read these lines on the inside front cover: ”Using clues from the text and peeling away the theological and scholarly interpretations that have often obscured the Bible’s most dramatic stories, Crumb fleshes out a parade of biblical originals.“ This is an important point which I will address in more detail later.

I pointed out some interesting things in Crumb’s depiction of God in the comments section over at Blogflumer, and defended it as the kind of subtle commentary and exploration of the text that people are claiming he doesn’t make. To address some of your points here:

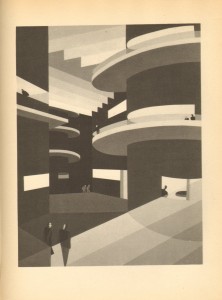

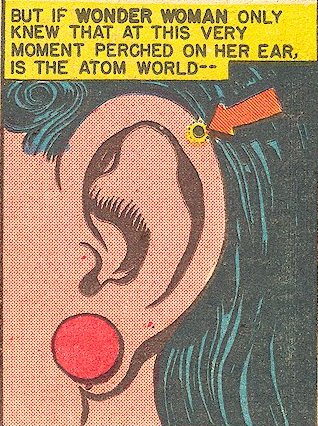

You claim that this line in Crumb’s notes: “after closely reading the beginning of the Creation, I suddenly imagined an ancient man standing on the shore of a sea, and gazing out at the horizon, and seeing only water meeting the sky”- is “an explication of his choice to so portray the Almighty.” It’s not. Crumb’s “ancient man” is not God, but to a man of ancient times trying to figure out his world. Crumb is describing the Hebrew vision of the universe (diagrammed here) and speculating about how they might have come up with it.

You say “one glaring problem” with Crumb’s traditional image of God is that “it conjures up all kinds of unflattering comparisons to his artistic forebears.” But I don’t find the examples you cite so unflattering; painters generally seem a bit uneasy with God the Father, which probably reflects a sense that the Almighty is not really like that, and the need to use the figure to tell the story.

“It also conveys an all too facile understanding of Adam being made in the “image of God” (imago dei), whether this is rooted in the theories and debates surrounding the terms “likeness” and “image” (e.g. in the writings of Irenaeus and Thomas Aquinas), the existential and relational readings of Karl Barth or the functional readings which altogether dispense with the idea that the “image” must consist of non-corporeal features [I think you mean “corporeal”] (i.e. the “image of god” as seen in man’s dominion over the earth and animals). This is but one indication that Crumb’s journey through Genesis was more personal and instinctive than cerebral.“

I must confess I didn’t reread my Irenaeus, Aquinas, or Barth for this, but could it be that their efforts to expand the meaning of “image” and “likeness” had more to do with a desire to reconcile their own idea of God with an ancient text than it did with determining the original meaning of the words? Whether or not you agree with Crumb’s references to the description of God walking in the Garden or sitting under the Terebinths of Mamre, or his assessment that “the God of Genesis is severe and patriarchal… he’s older than the oldest patriarch,” are they evidence of a “personal and instinctive” rather than cerebral approach?

You see his patriarchal vision of God as influenced by “the capricious Mesopotamian gods the artist is so enamored of” (lovely wording), but there’s nothing in his statement to suggest that, although the view that the Hebrew’s God had its roots in such figures is that of historians and Robert Alter. (Many Christians don’t have a problem with the notion that humanity had an evolving idea of God.)

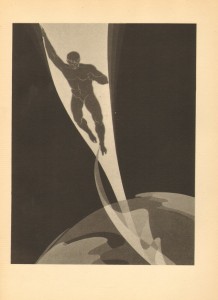

However, there is a sense in which his choice is personal, as he’s said this God resembles his father and came to him in a dream. (From the Paris Review: “He was warning me about something… about some destructive force that was getting stronger… he was enlisting me to be one of the people to protect this reality from that force. When I was trying to figure out how to draw God I remembered that image, which I could only look at for a split second, it was painful to look at this face, it was so severe and anguished… I tried to [give him that face in Genesis]. It doesn’t quite capture it. That was my reference point. All the way through I would go back and rework the face, I kept whiting it out and redoing it, to try and get it right.” This actually resembles the last appearance of God in the book, to Jacob in a dream- see if you agree.) But can you reconcile that with your claim that Crumb had no emotional investment?

Finally, can we admit that Crumb could plausibly have had an interest in using this figure, with his unusual physical presence that I’ve described elsewhere, to startle us and make us consider our own concept of God, and what the concept, and the idea of having encounters with him, might have meant for these people at the time? Or is “deconstructive” a credit we only give to dystopian superhero comics?

You write,

“Crumb’s almost anti-intellectual approach to Genesis continues to pose difficulties throughout the rest of these two chapters.

“While few would question the rigor with which the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is drawn, it remains at best only a fruit bearing tree. One might view the central image of the tree of life (many branched, filled with knots and ramrod straight) as a representation of the masculine ideal and the tree of knowledge in the background as the curvaceous and deadly feminine, but there is little beyond this to recommend it.”

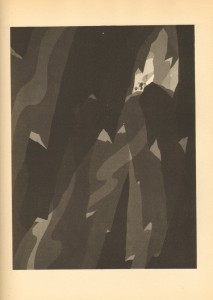

Let’s look at the illustration more closely. It’s arresting. The tree of life centrally and powerfully dominates the composition, with a “ramrod straight” trunk, as you say, until it reaches a mass of exposed branches, each vivid and separately delineated- so clear, in fact, because they are bare of foliage. The leaves only appear around the outer edge, like a brush. This is such an unrealistic effect that it’s obviously deliberate.

So why do you think Crumb did it? To me, the image suggests a genealogical table. By contrast, the tree of knowledge of good and evil squats in the corner, visible but less differentiated from the dark woods. It’s low, undulating and twisty, with a negligible trunk and branches that cover one another before they’re cloaked with a huge mass of leaves. What might that say about “knowledge of good and evil”? We don’t have to treat this like an English class, but surely he wants to make us consider the issue. Is “only a fruit-bearing tree” fair? (You suggest it’s a contrast of masculine and feminine, but that might be a mistake to see in an artist who’s stated his intention to bring out the buried evidence of a matriarchy that lived on equal footing with the patriarchy [shown in his repeated drawings of Adam & Eve standing together with God behind them]- although I agree the trunk for the tree of life is phallic.)

Another interesting feature is that only the tree of knowledge of good and evil has fruit. Like so many details, this is founded in the text. God commands Adam, “From every fruit of the garden you may surely eat. But from the tree of knowledge, good and evil, you shall not…” There is no prohibition against eating from the tree of life. There is also no reference to its having fruit. God says, “Now that the human has become like one of us, knowing good and evil, he may reach out and take as well from the tree of life and live forever.”

A less attentive artist would simply have drawn the tree of life with fruit, but Crumb has addressed a textual problem. If God didn’t want them to eat from the tree of life, why didn’t he forbid it? Why did he tell them they could eat from every fruit in the garden but that of the tree of knowledge? Another telling detail is that the tree of knowledge is quite low, with fruit that’s easy to grab. But whatever the humans might take from the tree of life, they’d have a hard time, because the branches are so far off the ground. God never prohibits them from eating from the tree of life, although he fears it after they take from the tree of knowledge. Did it not occur to him because they wouldn’t have been able to?

His answer doesn’t quite solve the problem, is not the only possible one, and may just address a meaningless oversight of the writers. But Crumb caught it and attempted to make a coherent story the story from the words (something you repeatedly claim he doesn’t do.) The reader can accept or reject this explanation as he pleases; after all, every word is right there, and I think that’s important to Crumb’s method of exegesis. (It’s not the clamping down on possibilities Alter describes.) Crumb offers a possible answer while calling attention to the problem- I’d never noticed it.

Back to you: “What we don’t find in these illustrations is any evidence of the speculative richness the idea of the tree of knowledge has evoked through the ages; be they the ideas concerning sexual awareness proposed by Ibn Ezra, the capacity for moral discrimination, the granting of paramount knowledge or the bestowal of a divine wisdom.”

But Crumb did not set out to address the speculations of Ibn Ezra and the ages, he set out to explore the original text. You appear determined not to perceive this.

“All that we find in The Book of Genesis is a personal mythology influenced in sections by the somewhat discredited theories of Savina Teubal (which I should add is still preferable to the alternative of unthinking transcription…“

I could have done with less Teubal myself, but I think I’m showing how Crumb’s work is hardly “unthinking transcription”. “Personal mythology” is wildly inappropriate given Crumb’s minute fidelity to the text.

“In much the same vein, the encounter with the serpent in Genesis chapter 3 is reduced to a flaccid conversation with a walking reptile. Adam is absent throughout this version of events, though the presence of the plural form of “you” in 3:1-5 suggests he is with Eve but not deceived like she is.“

I’m no expert, and certainly the kind of beginner you concede might like the book, but couldn’t the serpent’s plural address refer to God’s having given them a command that applies to them both? (“Though God said you shall not eat from any tree of the garden-”) I can easily imagine a conversation with a lone Eve where he addresses her this way. If Adam was present, why does God tell him, “Because you listened to the voice of your wife and ate from the tree…” If he was there to hear the serpent, wouldn’t he have been listening to his voice? Likewise, he defends himself by saying “the woman gave me from the tree”, and the story describes her giving it rather than his taking it from the tree. In any case, it all starts with “The serpent said to the woman…” There are many suggestions that Adam is not present, and we’d need a Hebrew scholar to settle the one that might.

“Crumb sticks to his vow of straight illustration, refusing to explore the reasons for Adam’s acquiescence despite his absence from the serpent’s exchange with Eve in this account.”

True, he could have shown Eve caressing and tempting him, although that would have been more in line with later portrayals. Instead the panel is as direct as the line. What I like about it is that the ease with which Adam breaks the prohibition (“Oh, OK”) leaves Adam looking rather childlike, which I think is appropriate. It’s like two kids in the backyard; you run to answer the phone and when you get back they’re playing with a broken bottle.