I plan to do a number of posts blogging my way through n Moto Hagio’s Drunken Dream, released recently by our kind hosts at Fantagraphics. I’m a fan of Hagio’s work…or of as much of it as I’ve seen. (See my review of AA’.) And I have great, great respect for translator and editor Matt Thorn, (who was kind enough to facilitate the inclusion of this piece in an online project I did some years back.)

So basically I was hoping to be wowed by this book. And I don’t think that that’s entirely impossible even still — I skimmed ahead to reread “Hanshin: Half-God,” the one story here that was reprinted in TCJ #269, and that’s still awfully, awfully good (and I’ll discuss it in order in the next post or so.)

However, the first four stories do not live up to expectations. Because they kind of suck. And not just “suck in comparison to what I was hoping for.” They’re out and out crap — presuming you drew little hearts and flowers on your crap and maybe put a little schoolgirl dress on it, and then nailed it to a tree and sang to it odes about the transcendent power of art as it oozed with limpid bonelessness down the trunk to finally crunch ineffably on the leaf-strewn forest-soul.

Anyway. We’ll take them in order. (There are lots of spoilers here, if that concerns you. In fact, I pretty much spoil everything. Fair warning.)

Bianca

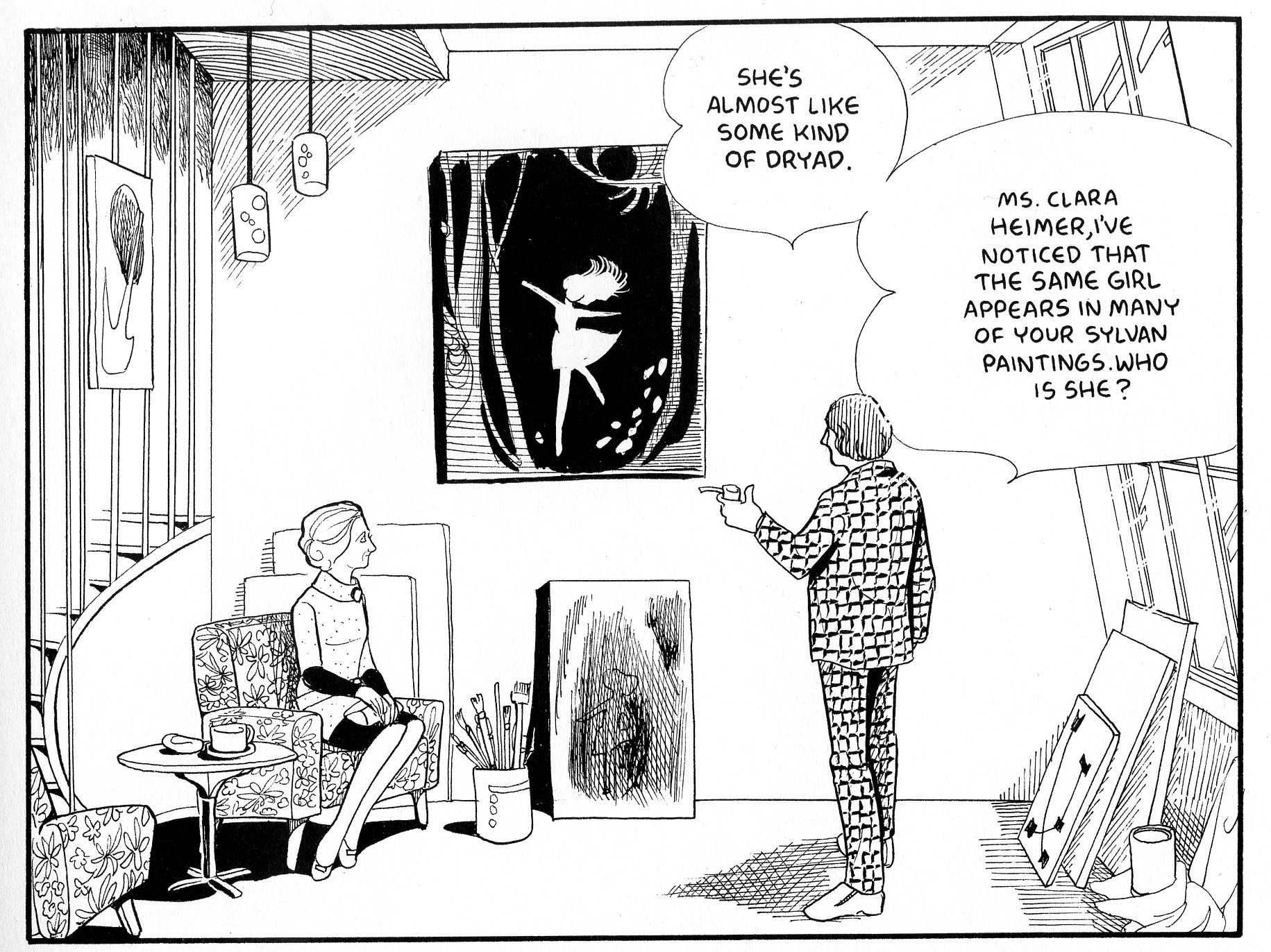

This is framed as a conversation between some guy with an aggressively patterned suit and the great painter Clara Heimer. Aggressive suit guy asks Heimer who that little girl is in all her paintings and she says it’s her lovely inner-child/nature spirit and then she looks up meaningfully as an infinite number of self-help books fall from the sky and crush her and the guy dead, leaving only the empty and aggressive suit to dance wildly, desperately, transcendently upon their moldering corpses.

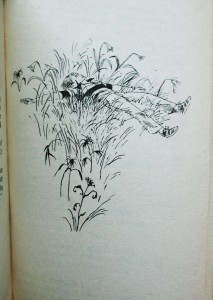

I wish. Actually she says the girl in the pictures is the titular Bianca, a young ten-year old cousin Heimer met for the first time when she was 12. Said cousin is a free spirit who cannot be contained, which translated means that she likes to run outside and dance in the forest “like some kind of dryad” as aggressive suit guy says. Clara doesn’t understand her free-souled cousin and makes fun of her dreams, causing said cousin to lash out and go dance in the forest some more. But, hark! Free-souled cousin also has a Dark Secret, which is that her parents are breaking up. The final news of their divorce sends free-soul (you guessed it) back out into the forest, where she is so distracted that she falls off a convenient cliff, taking herself mercifully out of the story. But she has, alas, inspired Clara forever. Or as Clara says, “I saw the wind. I saw a dancer. I saw the world of a girl who became one with the forest.” So Clara goes on to spend the rest of her life drawing trite dryad pictures about the wounded child inside all of us and how the trembling spirits need to be free and how you shouldn’t make fun of people’s dreams no matter how clichéd and irritating they are. Let’s…let’s save all the children. Save the babies…save the babies…

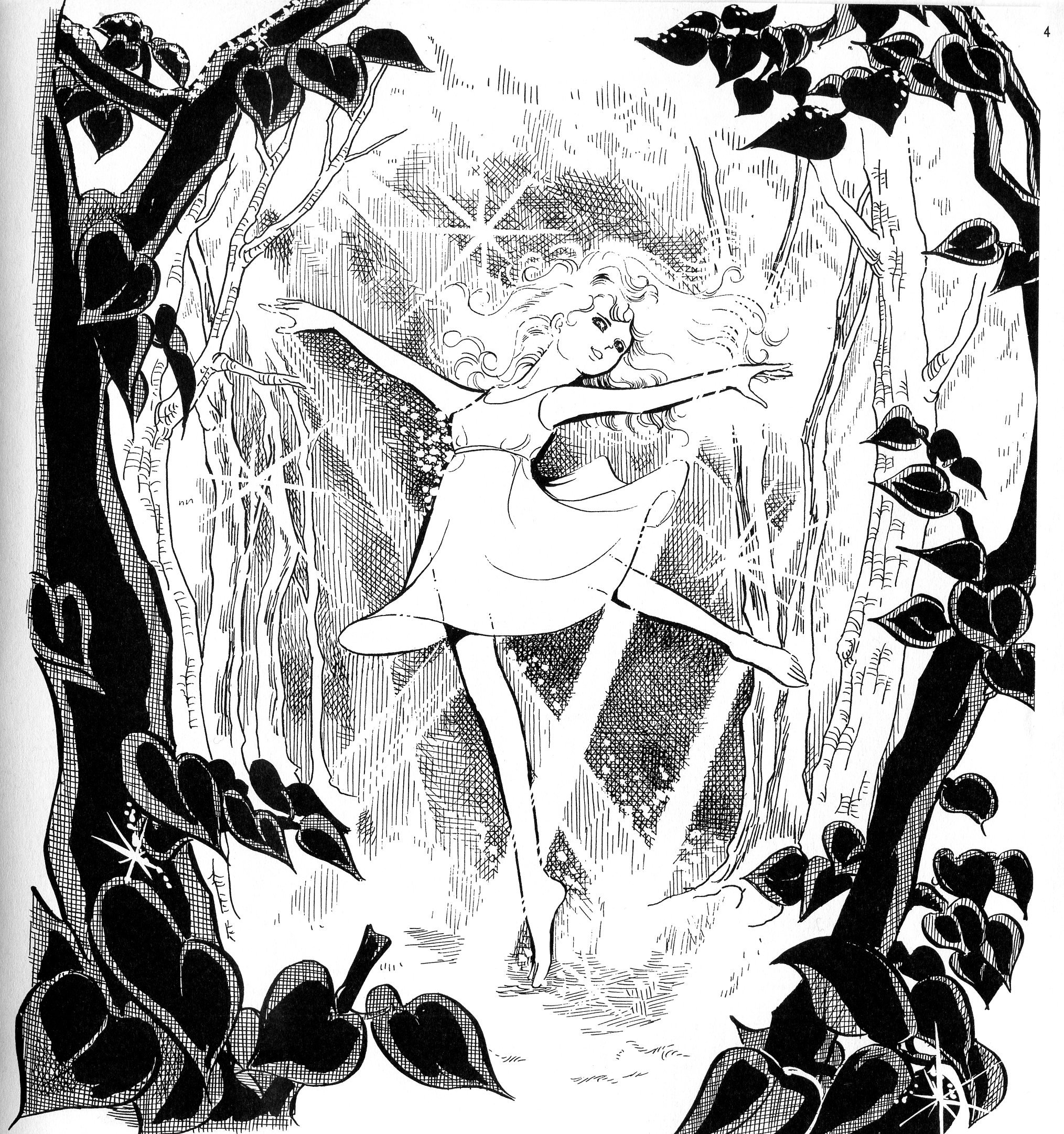

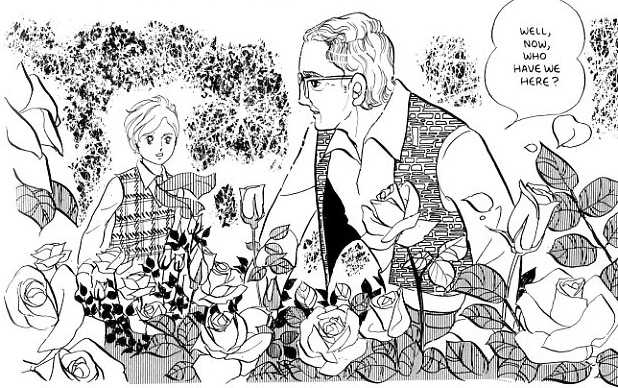

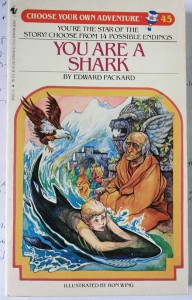

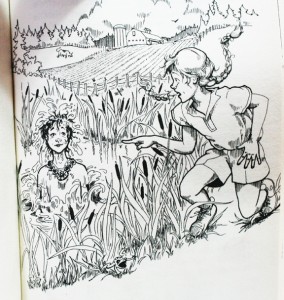

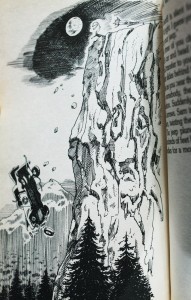

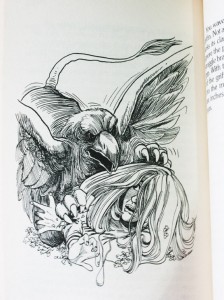

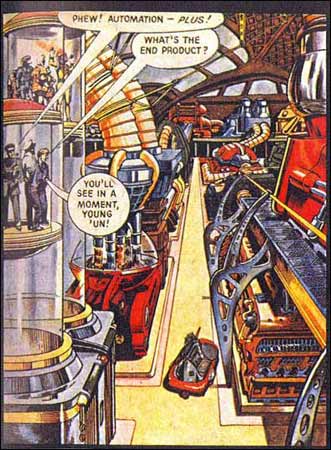

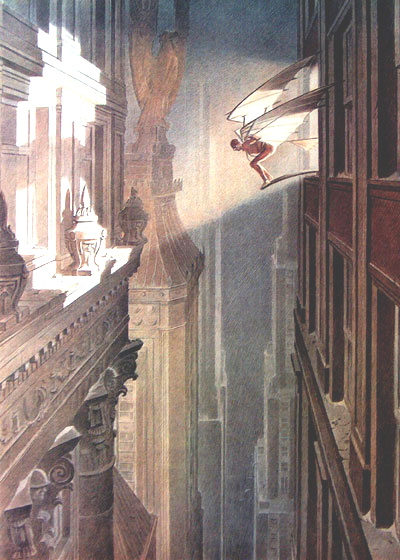

Here, look. Save this, damn it!

The light and trees criss-crossing; Bianca in the center with the airy thin lines of her dress — it’s impressively designed. But it also seems too perfect, with those trees at the side conveniently framing the imge, and Bianca herself stuck dead center. Her pose even makes her look like she’s a decoration on a cake. Hagio’s style is delicate and pretty; layered on this delicate and pretty narrative, it just makes the whole thing so precious it’s hard not to gag.

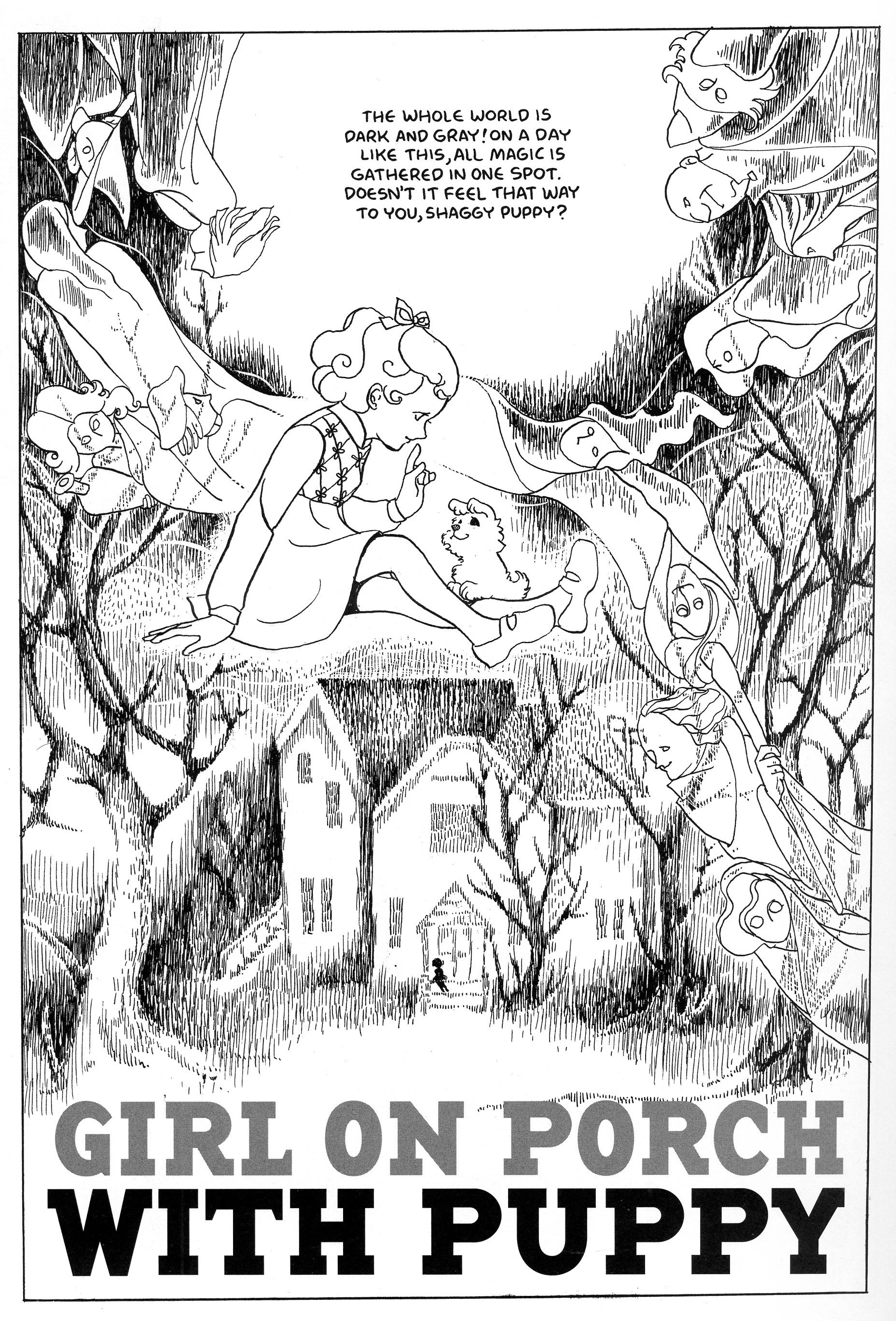

Girl on Porch with Puppy

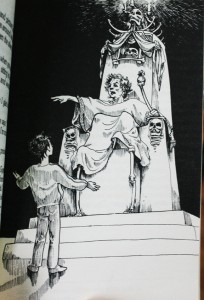

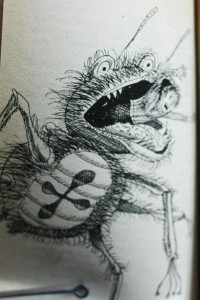

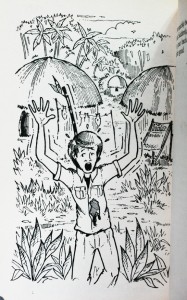

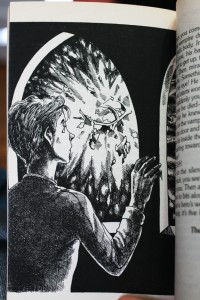

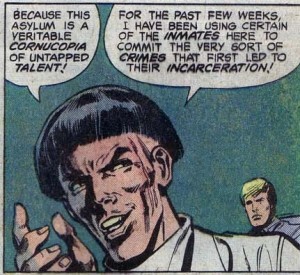

The opening visual here, on the other hand, uses pretty to contrast with creepy — which only makes the whole thing more disturbing.

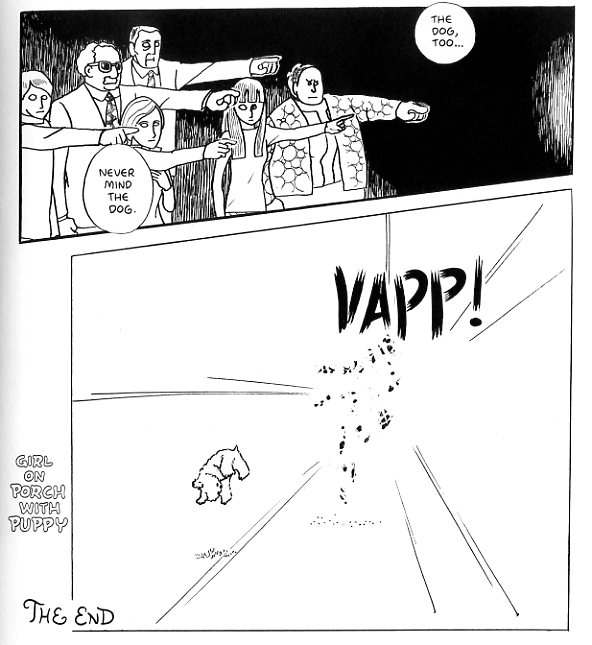

I wish those weird, semi-faceless ghosts hung around for the whole story. Unfortunately they don’t. Instead, as far as narratives go, this is basically more “Bianca”, except worse. Like the title says, a sweet little girl sits on the porch and communes with her sweet little lap dog. Various adults (doctor, mother, father, etc.) wander past and wonder what’s up with her and/or express disapproval because she likes to sit outside in the rain. She muses self-consciously about vapidly trite saccharine hallmark card drivel and about how much more wonderful she is than boring old adults (“I don’t know what the doctor’s thinking either. But I don’t think it’s about the sky or windows or flower buds or the fairies behind the leaves”).

So the boring old adults get together and decide “we can’t have one person thinking differently from everyone else like that.” Then they point at her and she explodes. Admittedly, it would have been better if they did that on the first page rather than the twelfth. But beggars can’t be choosers: it’s an unexpected but welcome happy ending as far as I’m concerned.

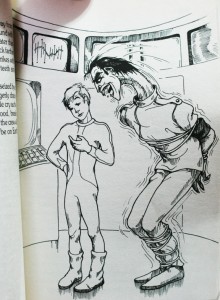

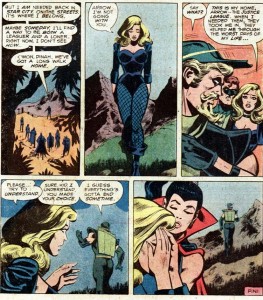

Autumn Journey

A young boy named Johann sets off to meet his favorite author, Meister Klein. He ends up hanging out with Klein’s daughter, and there’s some romantic tension, until…she discovers Johann is Klein’s son, from a family Klein abandoned. Johann isn’t mad at Klein, though, because he read one of Klein’s books and realized that “He had lived so much longer than I, known so much sorrow, and yet he told his stoires with such warmth, such sincerity.” You can tell he’s sincere because…flowers!

In short, if you’re a great artist, you can’t be a complete asshole and moral failure — an insight flagrantly contradicted by everyone from Pablo Picasso to Ezra Pound to Kanye, but what the hell. Johann’s enormous eyes leave little room in the skull for grey matter, so I guess he can’t really be held responsible for lapses in logic. Anyway, at the end his father runs after him as he rides away on a train. That’s redemption, kiddies.

Perhaps it’s not fair, but I’ll admit this is kind of a pet peeve of mine. Maybe it’s because I have a number of friends whose fathers walked out on them; maybe it’s because I’m a dad myself. In any case, leaving your kid flat in order to go start a new life strikes me as one of the most contemptibly loathsome things a person can do, definitively worse than any number of minor felonies. The idea that all is well if you write good novels and shed a few tears a bunch of years down the road — that’s just not okay. I mean, is this guy going to start coming through with child support or what? I know, I know — Hagio doesn’t actually care about such mundane issues, or, for that matter, about the characters or the moral issues as long as she can have her final tear-stained moment of sentiment and reconciliation. And you know what? That’s not okay, either.

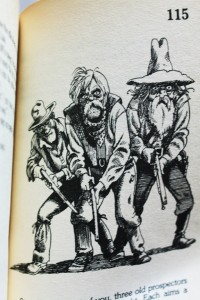

Marie, Ten Years Later

This is a classic love triangle; nerdy guy loves girl; hot guy loves girl; hot guy gets girl; girl dies mysteriously and conveniently; hot guy and nerdy guy get together and dance around the fact that they actually love each other and never really cared all that much about the dead girl; cue reminiscences about how happy they all were when they were young; fade out.

If this were by a guy, I’d definitely be pissed off by the way that the girl in question is reduced to a cipher for male (heterosexual and homosexual). But you know, since it’s by a woman — I’m still kind of pissed off actually. I guess maybe what saves it is the fact that the two guys are also utterly uninteresting, so even though we learn nothing about the girl except that the guys desire her, it doesn’t really feel like Hagio shortchanged her all that much. The insistent nostalgia by vapid characters for a vapid ill-defined past is irritating, but so empty it’s hard to get worked up about it. The first three stories really made me angry; this was just boring. So maybe that means this was my favorite of the four?

__________________

I’d like to think these were all juvenelia, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. The first three were from 1977 and the last from 1985 — Hagio wrote them in her late 20s and early 30s, by which time she was already an established and lauded mangaka. I’m forced, therefore, to conclude that Hagio is capable of producing dreck, at least some of the time. [Update: JR Brown in comments points out that the stories were actually printed earlier, before Hagio was established.]

Still, the kind and heft of the dreck are interesting. Sometimes you can get more insight into an artist from her failures than from her successes. Reading these stories it became clearer to me than it had before how much of Hagio’s work (or at least what I’ve read) seems to be about not just repression, but displacement. She’s obviously obsessed with themes of child brutalization and abandonment, the pressures of social conformity, and illicit love. But she explores these ideas through deliberate misdirection and metaphor, cutting the core of the stories loose from the material that inspired them so that the emotions suffuse the material, breaking through at unexpected moments or in odd ways.

For instance, in that first story, “Bianca,” the tragic dryad cousin who dies when her parents are breaking up — it seems likely that the break up problem stands in other problems, specifically physical abuse (which is much more likely than divorce to lead to a child’s death.) And, as I suggested above, Bianca is clearly meant to be the artist’s own traumatized childhood; a childhood linked, through the artist’s powerful feelings for Bianca, to repressed same-sex emotions. And love the can’t quite speak its name surfaces as a trope in virtually all the stories; the girl in the second is reprimanded for kissing her dog; in the third Johann is linked, teasingly but still, to a girl who is his foster sister; in the last, as I said, there are intimations of homoeroticism between men.

The point, for Hagio, then, are the buried meanings and how they resonate. This worked well in AA’, where the vague sci-fi setting turned everything into a metaphor; the world didn’t need to hold together since the world wasn’t real in any case. In contrast, the stories here are all too specfic; she doesn’t seem to have room to move around in them. “Bianca” and “Girl on Porch With Puppy” make their metaphors too straightforward, trilling “Flower Power!” over and over in piercingly crystalline tones. “Autumn Journey” and “Marie”, on the other hand, exist too firmly in the real world — they demand some sort of actual psychological insight on the level of character, while all Hagio wants to do is get to the darned emotional catharsis. Hagio is an artist who thrives on spaces and emptiness — she goes astray when, as in these stories, she tries to say what she means.