Charles Hatfield’s Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature, published in 2005, arrived at a time of immense excitement in the comics culture. The international new wave of comics had been changing the way we read and thought about comics for a good decade and were gaining an increasing institutional foothold, most notably in the cultural consolidation of the so-called ‘graphic novel.’ These developments are continuing, and comics, though increasingly visible institutionally, are still in a state of evolutionary flux. Hatfield’s book promised an in-depth analysis of this remarkable development, the objects of which he terms ‘alternative comics.’ But for all the book’s qualities, it did not fully to deliver on this, frankly seeming a bit of a missed opportunity. Books stick around however, and good books continue to inform and raise questions—a fact this ongoing re-evaluation at Hooded Utilitarian happily bespeaks.

But let me back up a bit and explain briefly the disappointment occasioned by the book’s promise. In surveying the emergence of this new ‘literature’, in the second chapter, Hatfield seems to stop just as he is getting to the interesting bits. Due perhaps to the relative lack of strong historical accounts of the last thirty years of comics history, he spends an inordinate amount of time discussing the underground and post-underground movements, from Zap to Love & Rockets, one could say. While these are of crucial importance to the emergence of the new wave, they are still arguably its constituents rather than its substrate. Perhaps Hatfield reasons otherwise, wishing to antedate ‘alternative comics’ by a decade or two, but if so, he does not fully explicate why we should collapse the distinction between periods that are usually seen to be connected but also somewhat distinct on grounds that range from the commercial to the social and the aesthetical.

This tendency is perpetuated through the book, which though showing an awareness of the new work that had been making waves for more than a decade at the time of publication—from Dan Clowes, Debbie Drechsler and Chris Ware to Julie Doucet, David B. and the Amok collective—concentrates largely on long-established underground/post-underground creators: Harvey Pekar, Gilbert Hernandez, Justin Green, Art Spiegelman. And as excellent as the individual analyses of their works are, they cannot help but make the book feel a bit retrospective.

Also, the fact that such large parts of the book are devoted to careful readings of a few select works takes away the momentum and sense of scale promised in the introduction and initial chapters. The importance of the featured creators is incontrovertible, and the issues Hatfield raises in his readings have been important to the development of alternative comics, but he seems reluctant to step back and diagnose larger trends or to exemplify them more broadly. This shortcoming is most apparent in the final chapter, which ostensibly joins the threads spun through the book and makes prognostications, but ends up getting lost in discussions of format that are no doubt important, but occlude the more pressing social and aesthetic discussion that at least this reader was hoping for.

Ultimately, the book reads like a reworked Ph. D. dissertation supplemented by disparate articles and conference papers—which I gather is what it is. It never satisfyingly coheres or expands in accordance with its promise. Since its publication, however, Bart Beaty has helpfully released his more tightly organized Unpopular Culture – Transforming the European Comic Book in the 1990s (2007), which despite its selective European focus does much to make up for the lack of a (roughly) contemporary critical history of comics’ new wave. And in any case, Alternative Comics contains such a profusion of illuminating analysis and compelling argument that it would be a mistake to dismiss for not being a different book than it is.

An obvious starting point for a critique of Hatfield’s book is its refreshingly trenchant and intelligently modulated, but also problematic casting of alternative comics as a ‘literature.’ I will refrain from debating the fundamentals of this issue, since Hatfield and Beaty have already discussed it in detail elsewhere, but I would like to point to some of its discontents as they manifest themselves in Alternative Comics.

Longtime HU readers will not be surprised at this, but it is my distinct impression that Hatfield’s literary point of departure blinkers him somewhat to the visual nature of comics. He is very sensitive to the medium as a narrative form, and to how both plot and character unfold sequentially in comics, but less to questions of how individual images work. In his elaborate chapter on Hernandez, for example, he emphasizes the artist’s “approach to drawing characters, which, though broadly stylized, nonetheless captures subtle nuances of expression and body language”, along with his panel compositions and transitions. But in his subsequent analysis Hatfield pays attention mainly to the latter, while composition is considered only fairly briefly, using basic cinematographic terminology, and style and graphic expression hardly discussed at all. Reading this lengthy and insightful essay on Hernandez’ work, the reader may be forgiven for forgetting repeatedly that she is reading about comics, not prose fiction.

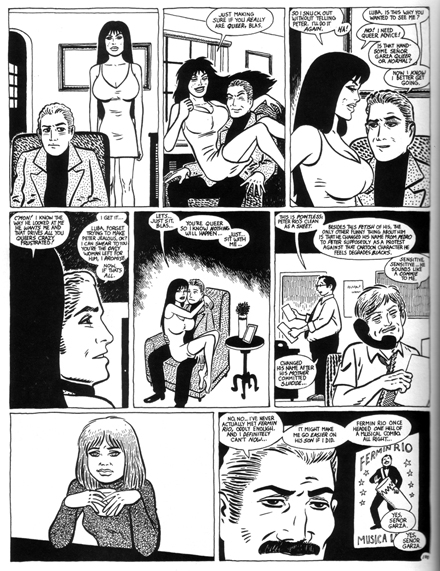

A more in-depth examination of Hernandez’ drawing style and visual choices could serve to address the charges of fetishization of women often leveled at the artist (in this debate by Noah), inserting it more fully into the context of masculine Latino culture, examined so compellingly especially in Poison River. This could be matched against similar emphasis on male genitalia in that and other stories or tempered by showing to what extent Hernandez suffuses his idealization with observation, suggesting in a few, deftly placed lines such physical features as flabby thighs, pocked cheeks, or tensed shoulders (all in the supposedly exploitative figure of Luba). It could be used to indicate how, by following the physical expression of a character like the ambiguous Blas of Poison River, one might sense the complex emotional motivations for his duplicitous behavior. Such examination of Hernandez’ visual understatement could then be seen in relation to his suggestiveness as a writer, and also to his simultaneous broadness as a cartoonist, which could again inform one’s interpretation of his constant insertion into Poison River of the racist cartoon stereotype of Pedro Pacotillo.

Hatfield’s literary bias has its most interesting consequences in his discussion of authenticity in autobiographical comics in chapters 4-5—arguably the richest part of the book. Because of comics’ history as a medium concerned almost exclusively with stereo-/archetype and the fantastic genres, realism and the notion of authenticity have been fundamental to the redefinition of the medium since the 60s, and remain a central concern for creators today, whether working with fact or fiction. This is potently evinced by the continued centrality of autobiography in the new wave of comics. Although he could have stated it more clearly and exemplified it more broadly, Hatfield is clearly aware of this and his analysis offers a valuable inroad into a discussion of how comics engage these qualities.

Having established the inherent fictitiousness in any attempt at autobiography, he argues that comics offer a special challenge to the idea of non-fiction, in that their narrative visuality literalizes its constructedness—the “original sin of logical coherence and rationalization” as he describes it, quoting George Gusdorf—by making immediate and graphic the artist’s self-/world-image and repeating it in sequence (as “multiple selves”). The inward takes outward form, impression and expression merge.

In what seems to me a misleading distortion, he then goes on to connect this to the concept of irony, analyzing a handful of meta-reflexive works by Pekar, Clowes, Crumb, Hernandez, Green, and Spiegelman. Cartoonists with claims to authenticity, he asserts, tend to express their truth through self-abnegation: by making apparent their subjectivity and the artifice of their voices—what Hatfield calls “ironic authentication.” In the midst of this, he evokes Merle Brown’s distinction between the fictive and the fictitious, assigning to the former works that ‘imply the art of their making’ and to the latter—which we sense to compromise artists claiming authenticity—those that ‘strive for transparency.’

Hatfield is on to an interesting aspect of how comics approach reality, both historically and currently. Since their modern beginnings comics have candidly integrated meta-reflexiveness into their concerns—from the zephyr blowing away the sketches at the start of Rodolphe Töpffer’s M. Pencil (1840), to Winsor McCay’s Little Sammy Sneeze breaking the panel borders (1905), to the implication of the authorial hand in Moebius’ Hermetic Garage (1976-80). Hatfield’s analysis is valuable for the way it highlights this remarkable aspect of comics as they have evolved historically, and how it is currently being employed in the service of newfound authenticity.

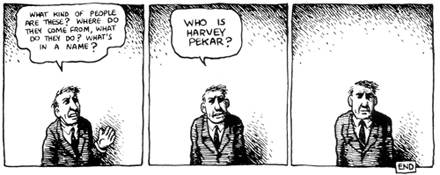

But at the same time it seems an overly theoretical explication for how and why most reality-based comics aspire to authenticity. These comics are not always as meta-reflexive as the ones cited by Hatfield. While such stories as “The Harvey Pekar Name Story” (1977; excerpted at top) and “A Marriage Album” (1985), mentioned in the book, are, most of that autobiographical pioneer’s work is not ironic or even particularly self-critical in its presentation. And Chester Brown, in his I Never Liked You (1991-94) especially, relates intimate emotional truths without a hint of irony of self-abnegation. Following Hatfield, this should compromise the feeling of authenticity in their work, relegating it to mere ‘fictitiousness,’ while the self-parodic exercises of Crumb, Clowes and Hernadez feel more real, but this seems to me wrong. Despite the inherent theoretical difficulties of doing so, might it not be that the former simply convey their sense of authenticity through more traditional means, such as evocative description and emotional resonance?

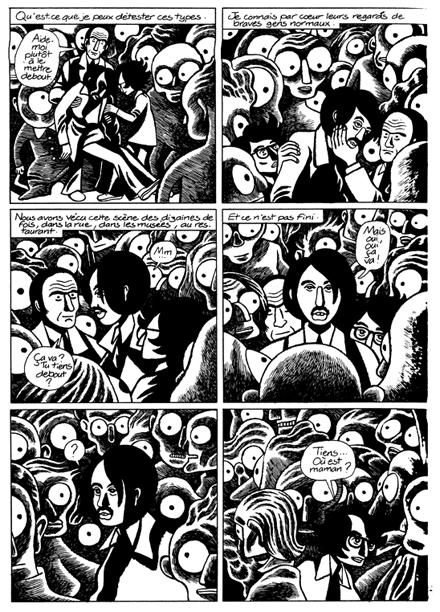

Furthermore, irony—while apt for several of the works cited by Hatfield—is simply too limited and loaded a concept adequately to describe the self-representation in many reality-based comics. In the present debate Caro has shown persuasively how this notion of constitutive irony collapses when applied in a female context, and I would argue that it is also problematic in the case of many male cartoonists, such as the almost entirely unironic David B., Fabrice Neaud and (the mature) Joe Sacco.

The basic problem with the hypothesis is that it assumes some kind of neutral, or ‘transparent’, mode of representation, which is supposedly subverted by comics’ graphic and narrative revelation of the creator’s hand. It is unclear how Hatfield conceives of such representation in visual form. It appears that he considers visual art as basically mimetic, i.e. imitative of the exterior world, which means that an artist or cartoonist aspiring toward self-expression must work “from the outside in.”

This seems to imply that naturalistic rendering, such as Neaud’s, for example would be closer to this neutral ground than cartoony drawing such as David B’s. There is some truth to this—Neaud’s reliance on photographs and his apparently accurate portrayal of friends and acquaintances contribute substantially to the feeling of authenticity of his autobiographical comics, but for this reader David B’s portrayal of his inner life seems equally authentic. Moreover, Neaud is, if anything, much more overtly occupied with his role as artificer than David B., who—while emphatically internal and symbolic—rarely expresses concerns about authenticity. And in any case, the work of both artists—and indeed any visual representation—is quite obviously subjectively constructed. In other words, the hypothesis of “ironic authentication”, as illuminating as it is and as useful as it might be, is founded in sand.

Again, I suspect that this has to do with Hatfield’s literary bias. His neutral ground, really, seems ultimately to be language, which he asserts works “from the inside out.” To be sure, the abstraction of language is less directly tied to visual phenomenological reality than images, and it is clearly ‘internally’ constitutive to our experience of same, but why visual experience would be less internal or why linguistic formulation of autobiographical narrative, or whatever else, would be less obviously artificial than visualization is unclear.

To round off: none of this is written to disparage what is a consistently thought-provoking book, which not only makes a strong case for comics as a complex art form—or literature—worthy of sustained study, but engages intelligently with many of the central problems faced by such study—not the least comics’ nature as visual language, or linguistic visualization.

__________________

Update by Noah: The entire roundtable on Charles Hatfield’s book is here.

Also, for those following the whole discussion — the roundtable is going to go dormant for a couple of days while Charles gathers his thoughts, and then he’ll reply to the points raised in a series of post at the end of the week.

I hope there are more comments on this; it’s a lovely essay.

I think you’re maybe not giving Charles enough credit in terms of his sensitivity to images. His chapter on form is at least as much focused on visuals as on language, and his discussion of the different modes of representation in Maus seems quite well done to me. Even the Hernandez bit — he really does discuss the iconographic fetishization. He does so in ways that I don’t find wholly satisfactory, but you seem to be saying that he just ignores it, which really isn’t the case.

Thanks for the link to the Beatty/Hatfield discussion too. I hadn’t seen that; hope to read through it in the next day or two….

Thanks, Matthias, for this extraordinarily well written and provocative response. In particular, I’m grateful for the discussion of problems or entanglements inherent in the notion of “ironic authentication,” a theme I’ll take up again next week in response to Caro’s post as well as your own. I believe that this roundtable has brought together some important objections or reservations on that score, and I know that my thinking on the subject will be importantly modified from this point forward.

If I may, I’d like to question your insistence on the book’s “literary bias,” which I believe is something of a straw target. Alternative Comics certainly is informed by the methodologies and aspirations of literary studies; there’s no denying that. In fact the literary “bias” of the book is not simply a bias, but an constitutive and defining perspective, that is to say, the disciplinary ground for the study. I can no more deny that, nor wish to, than I can deny that I went to graduate school in English and am an English professor. Alternative Comics had to be written first and foremost to a disciplinary audience.

But (and I’ve seen this not only in your response, Matthias, but also in other discussions among comics critics) I think that the concept of the “literary” is being invoked here as ipso facto proof that I must be blind to comics’ essentially visual character, and that is, I have to say, neither accurate nor quite fair. I believe that the way “literature” is construed in the book does not foreclose the possibility of examining comics’ visuality, a claim I’ve also discussed with Beaty in our Comics Reporter exchange at

http://www.comicsreporter.com/index.php/briefings/commentary/3370/

and in my newly published essay in the journal Transatlantica at

http://transatlantica.revues.org/4933

(in a special issue on comics studies co-edited by Beaty and Jean-Paul Gabilliet).

The book’s essential grounding in literary study (yes, it began as a PhD thesis in English) does not preclude it giving considerable attention to the visual, as indeed some reviewers have noted. Some readers don’t think it reads much like a conventional literary study at all! So what I want to suggest here is that there is a tendency to flatten out, or underestimate the scope of, literary studies and to assume that the book cannot cover important visual matters simply because it’s “literary.” Not so.

Any unanswered questions or shortcomings or gaps in the book are frankly due to my own work, not to some essential literary incapacity to discuss visuals. What I’ve found, along the fragile disciplinary borders, or stitches, that are necessarily a part of comics studies, is that there is tendency for readers to locate their dissatisfaction with the book in the fact that its perspective is literary. But in fact the book does considerably more with visuals than most such literary studies up to that point had done. So I think this invocation of a “literary bias” is a canard, and that the book’s silences or failings say more about the inevitable incompleteness of any single monograph than they do about the capacity of English profs to think visually!

I have always tried to take the most inclusive perspective possible, within the disciplinary parameters that I must work, and so I get particularly heated when it comes to fencing with accusations of “bias.” :)

Regarding the book’s take on history:

Perhaps Hatfield reasons otherwise, wishing to antedate ‘alternative comics’ by a decade or two, but if so, he does not fully explicate why we should collapse the distinction between periods that are usually seen to be connected but also somewhat distinct on grounds that range from the commercial to the social and the aesthetical.

Actually, I do explicate this at some length, though not in terms, I gather, that you find entirely convincing or adequate to the problem. I posit a historical continuity between underground comix and alternative comics but also note some of the signal differences between one era and the next, differences that make them “somewhat distinct.”

Here’s the thing: I continue to be bothered by a near-complete erasure in academic study of the underground comix, or rather an only glancing, semi-embarrassed acknowledgment, typically parenthetical or prefatory, of the underground comix. This to me represents a problem in the historiography of comics and graphic novels that my book set out to address. The prominence of the underground in my study, besides reflecting my genuine understanding of the movement’s importance, is also frankly a polemical move designed to foreground what academia has thus far been reluctant to deal with.

It is true that it would be a distortion simply to collapse alternative comics of the 1980s and 90s into the underground without observing their crucial differences; but it is also true, not so much in fan discourse perhaps but in academic study, that the undergrounds have been effaced, neglected, under-studied, perhaps even disavowed as an important point of origin. (The happiest sign of change in this department was the U of Florida “Undergrounds” conference in 2003,

http://www.english.ufl.edu/comics/2003/ ,

which happened during the late revisions of my book.)

So, in a nutshell, I see my emphasis in this area as a corrective to a willed oversight. Bear in mind that Alternative Comics was meant to be an intervention in an academic discourse as well as a contribution to a more general critical one.

…though showing an awareness of the new work that had been making waves for more than a decade at the time of publication—from Dan Clowes, Debbie Drechsler and Chris Ware to Julie Doucet, David B. and the Amok collective—concentrates largely on long-established underground/post-underground creators: Harvey Pekar, Gilbert Hernandez, Justin Green, Art Spiegelman.

Ahem! More defensiveness here:

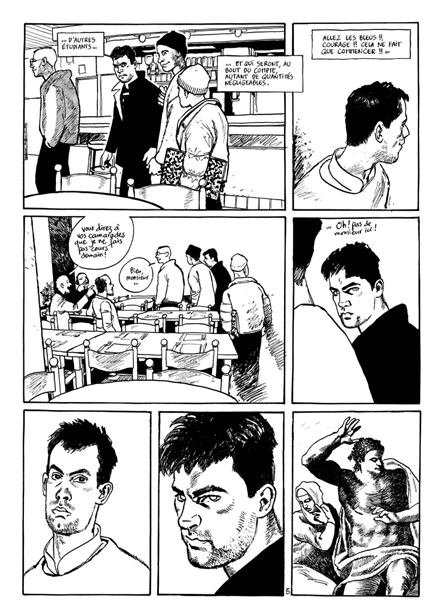

At the time of the book’s drafting, figures such as David B. and the Amok collective were virtually unknown in anglophone academic study despite their tentative inroads (particularly David B.’s) into the US alternative comics market. Indeed I was exposed to Amok via direct experience at the International Comic Arts Festival (now Forum), which hosted Yvan Alagbé and Olivier Marboeuf in 1998 (and, as an aside, was also instrumental in introducing alt-comics/SPX fans to other important artists such as Dupuy-Berberian, Rutu Modan and the rest of the Actus group, Martin Tom Dieck, and Anke Feuchtenberger). At that time only a small handful of North American comics shops carried work from alternative European publishers such as L’Association, Amok, or Cornélius, and such works’ exposure even through critical outlets such as The Comics Journal was minimal, though by the late 90s Beaty’s essential “Euro-Comics” column was doing important work that influenced me greatly. I took great pride in selecting and seeking permissions for images from untranslated European BD in my book.

I agree that Alternative Comics has a retrospective quality now, a topic I’ll address again next week, but (a) retrospection is not necessarily a bad thing, if one’s aim is to set forth a history, a context, a narrative of a field’s growth; and (b) the book does pay attention to many more recent comics than those of Crumb, Green, Pekar, etc. I would have thought that this integration of the (then) “new” with the “old” would be one of the book’s strengths.

For me the single biggest irritant in the discussion of Alternative Comics is the criticism of its selectivity and omissions. I won’t deny that there are omissions in the book, but since I such took such pride in its inclusiveness, it’s always a blow to be told that it wasn’t inclusive or current enough. :)

LOL, Charles said:

I’ve been trying to burn this straw man for months.

Matthias, if I ever meet you face-to-face, I’m gonna buy you a great big flaming tiki drink in order to ritually burn it once and for all.

:)

My interest in the undergrounds as a whole is pretty much nonexistent…but I found you’re discussion of them pretty fascinating Charles. Particularly the link you made between the undergrounds, fan collectors of older material, and the creation of the direct market made a little light bulb go on in my head. Now I get why I’m supposed to love Kirby *and* Crumb….

Charles discussion of the Undergrounds was way more interesting than that found in the Abrams book on underground “comix” (Underground Classics Transformation of Comics into Comix by James Danky & Denis Kitchen) which I found really banal. (I was reading to try to gain some context/appreciation, but it failed to convince me.)

Heh, I knew bringing up that particular subject would seem a bit predictable. Sorry about that, I shall perhaps try to place a moratorium on myself for a while.

For the record, however, I never said I believed someone working from a literary perspective is inherently unable to comment intelligently on the visual aspects of comics, and in any case I appreciate the strongly stated position you’re taking in the book, Charles.

The sense I got from reading the book, and from your talking about your motivations with Bart, is that your interest in comics was (is?) primarily oriented towards storytelling. You pay a lot of attention to storytelling and braiding throughout the book, but I missed a little more sensitivity to how the images look and work. Especially in the Hernandez chapter, where the passage I quote is never really followed up or exemplified.

Sure, you mention often *what’s depicted in a given panel or sequence, but don’t really discuss *how it’s depicted more than superficially. This is less pronounced in other sections of the book, such as chapter 2 and the section of Maus, but I still thought that overall the book could have benefited from greater attention to this aspect of the comics.

My impression was that your ‘literary’ focus on plot and sequence perhaps occluded those aspects in your analysis, but that is of course merely my supposition.

As for your selection of artists and works it is indeed very broad, and I wasn’t so much complaining specifically about who made it in or not, but rather that the book seemed to promise a more in-depth analysis of what I describe as the ‘new wave’ of comics in the 90s onward, rather than the comics — underground and post-underground — that preceded them. You do mention a lot of the 90s artists and their works, but mostly in passing, and end up focusing much more on their predecessors. This is not just me rationalizing now, five years later — I remember distinctly having this feeling when the book came out.

I sympathize a lot with your agenda to revive academic interest in the undergrounds and, as I wrote, can only applaud your work in this regard — the result is just another book than the one I had initially hoped for. Which is really no problem, since what’s there is both necessary and good.

Matthias:

“This tendency is perpetuated through the book, which though showing an awareness of the new work that had been making waves for more than a decade at the time of publication—from Dan Clowes, Debbie Drechsler and Chris Ware to Julie Doucet, David B. and the Amok collective—concentrates largely on long-established underground/post-underground creators: Harvey Pekar, Gilbert Hernandez, Justin Green, Art Spiegelman. And as excellent as the individual analyses of their works are, they cannot help but make the book feel a bit retrospective.”

In other words, why waste time on the old-timers? Why not seek out the newest, hippest artists instead?

Not your finest moment, Mr Wivel. I can assert that Green’s ‘Binky Brown’, Spiegelman’s ‘Maus’, Pekar’s ‘American Splendor’ and Beto’s ‘Palomar’ have already given robust evidence of standing the test of time. Whether your counter-examples will do as much is up in the air.

Fashion and trendiness are poor guides for scholarship.

Alex, you misunderstand me — those are all great comics. The problem I had was that the book seemed to be/was promising a treatment of the new wave of comics, not an account of how the underground/post-underground movements made it possible, which it was it ended up being (and re: the underground; Patrick Rosenkrantz’ great book had just come out, covering that better than anything else).

But as I said, it’s fine — it’s a deserving subject and those are all deserving works/authors, so I have no problem with it per se. It just appeared like faulty declaration to me.

Matthias, can you clarify for me what you mean by this statement?

“Constituents” and “substrate” is a little bit of a mixed metaphor and I’m not sure whether I’m mapping it right. Do you mean that these are actually part of the new wave rather than its antecedents? That doesn’t quite make sense with your saying there’s a retrospective quality.

=================================

As much grief as I give you about your use of “literary”, I do feel that in what you perceive as “something missing” there’s a legitimate pedagogical issue, at least for me personally: literary scholars learn the toolkit of literary formalism and close reading very systematically and from certain types of books: glossaries of literary terms, applied grammars, and the New Criticism. Art history doesn’t appear to have a similar literature that can be put to similar pedagogical purposes.

When I first started working in visual culture, I asked art historians for recommendations of comparable books, and by in large, with very VERY few exceptions, what they recommended was history. History isn’t formalism — formalism is specifically not historical. In comparison with, say, Cleanth Brooks, art historical writing about the “visual elements” of art seems arbitrary. And yet the neophyte art critic is expected to cull the “proper” vocabulary and descriptors out of these articles that focus not only on a narrow set of images at the same time (as opposed to a glossary that covers a full range of literary devices and techniques) but also heavily on non-formal elements, treating formal elements “in context” and in a less systematic way (less in comparison with New Criticism, I mean).

Culling that perspective to the point that one can speak to visual elements at a sufficiently in-depth level to satisfy what you seem to be asking for is extremely difficult. There’s a territory between the technique-focused vocabulary of studio art and the history-focused context of art history that appears to be not nearly as well documented in art criticism’s pedagogical texts — or if it is well-documented, nobody’s given me the right recommendation yet!

I’m happy to be corrected on this as I’d dearly love to read those texts and up my chops on writing about those elements! But I think its an extremely important issue that your cry of “too literary” gestures toward but doesn’t actually solve…

Hi Caro, thanks for pointing to that vague formulation — “constitutive” and “substrate” would tend to get confused — I should have been clearer; what I meant was that the ‘new wave’ wouldn’t have happened if there hadn’t been an underground and a post-underground, but that they are not directly part of the ‘new wave’, they are not integral to it.

As for formalist terminology for art history, there is plenty, although you’re right that it’s nowhere near as consolidated as in literature studies. This probably at least in part has to do with images being harder clearly to describe in formalist terms than language. And yes, in many cases, it is best to read what you call “histories”, or at least subject-specific texts: Meyer Shapiro and Roger Fry on Cézanne, John Berger on Picasso, Kenneth Clark on Rembrandt, John Shearman on Raphael, Martin Kemp on Leonardo, Michel Fried on Manet, etc. etc. (not all of this is formalist, of course, but all offer inspirational writing about images).

But: I would begin with the founders of art historical formalism: Alois Riegl (esp. “Problems of Style”, “Late Roman art industry” and “The Group Portraiture of Holland”) and Heinrich Wölfflin (esp. “Principles of Art History” and “Classic Art”). These are all published in English in various editions. Both scholars were exceptionally sensitive analysts of visual art and well worth reading, and much of their terminology is still in use.

The field of iconography of course is also crucial to the development of art history as a discipline, and here Panofsky is obviously your first stop: I would suggest “Perspective as Symbolic Form” and “Studies in Iconology”. Much has happened since then and the approach has been heavily problematized, but no one integrated encyclopedic knowledge with visual intelligence like Panofsky.

Beyond that Gombrich’s many books are great for their synthesis of solid old school art history and a more theoretical approach that provides a bridge to the theoretical directions of the latter half of the 20th century.

That’s what I can think of at the spur of the moment — there’s much more naturally, but those remain foundational.

As far as I remember, Donald Preziosi’s “Rethinking Art History: Meditations on a Coy Science” is a good overview of the tradition and an signature work in the 80s efforts to open art history to the wider theoretical field that it had largely been ignoring until then (his “The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology” is also a good overview os possible directions anno 1998).

One of the essential differences between the study of literature and visual art, of course, is the latter’s foundation in concrete objects. There’s a whole literature out there dealing with technique and such, but that takes us beyond your question I guess.

Caro,

I’m not sure of the extent to which literary scholars (i.e., at the graduate level) learn “the toolkit of literary formalism,” etc. I suppose it varies between graduate programs.

On the question of “toolkits” for the analysis of pictures, John Willats’s “Art and Representation” is worth a look. Also, Patrick Maynard’s “Drawing Distinctions.”

At the same time, it seems that many items from the classic literary toolkit that one finds, e.g., in M. H. Abrams or Northrop Frye — metaphor, synechdoche, allegory, allusion, etc. — have been made to work for visual analysis as well.

Jonathan, considering that I had a colleague in my PhD program in English who was specializing in English Composition and rhetoric but had not learned what a participle was, I’d say you’re exactly right. :)

Thanks to both you and Matthias for the excellent reference. Some but not all of Matthias’ are ones other art historians pointed me to but there’re definitely some new ones there, and the Willats and Maynard are both new. Thanks!

I wonder how Matthias feels about adapting the literary toolkit to visual analysis…is that “too literary”?

You’re welcome.

In principle I have no problem with adapting terminology — it depends on how you do it. I haven’t seen a whole lot of it in art history, I don’t think, beyond very general terms such as “allegory” and “metaphor”, which are used widely, and then of course the whole structuralist/post-structuralist apparatus, the application of which I’ve generally been less impressed with.

But yeah, anything that works is good in my book, as vague as that sounds :)