This was first published on Splice Today.

_________________________

Johnny Cash has been my favorite performer pretty much as long as I’ve had a favorite performer. When I first heard those bleeps on the Folsom Prison album, I was young enough that I actually didn’t know what was being excised. I first learned what “curfew” meant when I asked my parents what Johnny Cash was getting arrested for in “Starkville City Jail.” I’m not certain at this late stage, but I think that same song was the occasion for my first introduction to the concept of controlled substances (“he took my pills and guitar picks/I said, “Wait my name is….”/”Aw shut up”/”Well I sure was in a fix.” And no, I didn’t look the lyrics up.)

As a kid I was, like lots of kids, given to some fairly abstract daydreaming, and Johnny Cash figured in those as well. Specifically, I spent a certain amount of time wondering why people thought musicians in general, and Johnny Cash in particular, were cool. Obviously, Johnny Cash sang about shooting people and getting into fights and getting thrown in jail, and at that time he was associated with the outlaw country movement. But I knew he wasn’t actually an outlaw — he was just a singer. He didn’t even always sing about being a tough guy; sometimes, for example, he sang about political squabbles among bandmates (and yes, “The One On the Right Was On the Left” was how I learned that left and right were ideological as well as directional.) So…if he was just a guy standing up there with a guitar, what was so mysterious or special about that? I turned it over in my head on long car trips while we listened to his cassettes in the back seat, thinking of him standing on stage (I didn’t know he wore black then) and of people watching him, and wondering what, exactly, they saw when they did.

I’m a lot older now, obviously, and know my political left from right and why a sheriff might take your pills and what shit precisely you bleep. But why we idolize musicians, or artists of any sort, remains in many ways a mystery. What is it about art that commands worship? Why do we want to reverence somebody because they happen to be able to sing? It’s a particularly open question with someone like Johnny Cash, who was neither a musical innovator — like, say, Elvis — nor, in any sense, a vituoso — like say, Merle Haggard or Willie Nelson, both of whom could sing rings around Cash.

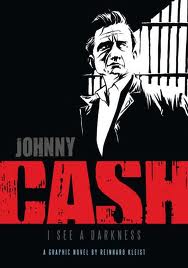

Of course, there are various ways to explain the glamour of Cash — or indeed of any artist. Reinhard Kleist’s graphic biography, Johnny Cash: I See a Darkness dutifully deploys most of them — a number in the first few pages. Right off the bat we hear from the lips of prisoner and singer-songwriter Glen Shirley that Cash “is our guy.” “The man is a story-teller. He lives his songs,” Shirley gushes. “And in them you can find every chasm an’ every low of this shit life.”

That’s actually Kleist speaking through Shirley, no doubt; the book casually attributes dialogue where it’s convenient, and makes no pretense to any sort of scholarly accuracy. Still, I doubt the real-life Shirley would have minded too much; Kleist’s summing up of Cash’s appeal is familiar country music boilerplate (“he’s authentic!” “he’s honest!”) Other standard tropes wander through the book as well — Cash is bold and uncompromising! He understands darkness because there is darkness within him! He has suffered!

It’s not that I think any of this is wrong exactly. Often though, it begs the question —I mean, lots of people have withering drug addictions and do stupid crap, which does maybe qualify as darkness but doesn’t necessarily qualify as special or interesting.

Moreover, in Kleist’s hands, what insights there are all fall flat. This is most painfully evident in the numerous illustrated songs. Kleist provides images limning the narratives of a number of Cash’s big hits, from “Ghost Riders in the Sky” to “A Boy Named Sue” to “Ira Hayes.” The point, I guess, is that since Cash lived through his songs like Kleist/Shirley said, it makes sense to include them in his biography.

The exercise does affirm Cash’s power as a story teller, mainly through contrast. Kleist is a pretty good artist — his drawing of a young Johnny standing at the microphone, head cocked, preparing to deliver “Big River” is lean and striking, for example. But the effort to show the narrative itself is determinedly bland — images of the mooning swain and his traveling lover lack the lonesome sparseness of the sung original, not to mention its barely contained, self-parodic humor. The pictures seem generic, taken out of any Twainesque riverboat setting, where the original reveled in its specificity as Cash’s deep baritone caressed each place name and ventrioloquized voice, (”A freighter said, ‘She’s been here, but she’s gone boy she’s gone.’”) It’s like Kleist decided to draw the sequence without ever stopping to wonder what made the song worthwhile in the first place, with the predictable result that he gets the general framework and leaves out the soul.

The failure to think things through is evident in the narrative proper as well, in both large ways and small. The decision to mostly skip the 70s, 80s, and 90s, ending the story with a reverent glimpse of Cash chatting with the sainted Rick Rubin is, I guess, inevitable, but still irritating. Similarly, a brief sequence with Bob Dylan had me gritting my teeth. The dialogue itself, seemingly lifted from session tapes, was interesting enough (after hearing “A Boy Named Sue” Dylan calls it “funny but a little silly.” Pompous prick.) But the context of the encounter, and the work it does in the story, is facile. Dylan points out the evils of Vietnam and attempts to get Cash to smoke some pot. Cash defends the G.I.’s , avoids the philosophical discussion, and sticks with pills.

So we’ve got the liberal rebel who knows the world and the more plodding everyman with a conscience, the two burying their differences and making common cause across the bridge of music. Which, again, isn’t categorically wrong, but does finesse the point that they’re crossing that musical bridge in no small part because Cash was a humongous Dylan fan. In one of his autobiographies, in fact, Cash talked about playing The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan over and over obsessively — listening to it all day up to the moment he went on stage to do his own show, coming off stage, and immediately putting it on again. Cash covered a number of Dylan songs too, and his version of “It Ain’t Me Babe” is, to my mind, inarguably better than the original, veering, from bleak poetry to overemoting silliness in a way that the supposedly-mercurial-but-actually-in-general-fairly-monotonous Dylan never did.

Dylan’s a recognized genius if anyone in pop music is, and putting Cash next to him is clearly supposed to be validating. But, at least for me, the whole sequence actually obscures what’s worthwhile about Cash. I guess that’s inevitable. The reason you like an artist is their art; staring at the man or woman behind it is kind of the definition of missing the point.

Still, I wish Kleist had managed to get at a little more of what I love about Cash— the achingly sublime contrast of jaunty banjo and Cash’s halting hum on “Any Old Wind That Blows;” the bizarre detour into aborted self-immolation while wearing duck-head overalls in “Beans for Breakfast”; the way his deep, ragged, almost spoken vocals contrast with Anita Carter’s angelic tone to make his version of “Were You There” one of the two or three greatest country gospel songs of all time; the way his deep, ragged, almost spoken vocals contrast with June Carter’s sexy growl to make his version of “What’d I Say” perhaps the most gloriously, hilariously failed white soul song ever. And, yeah, the way that a seven year old could learn right from left and what a curfew or an amphetamine was by listening to him, just because his music was so filled with stuff and so engaged with the world.. I See A Darkness sounds sexy and cool and all, but really the guy saw all sorts of things. That doesn’t make him a romantic icon to reverence necessarily, but it sure makes his songs fun to listen to.

I wonder if the Dylan/Cash conversation is based on fact. It’s hard to imagine Dylan talking about the evils of Vietnam to anyone.

You think so? Dylan was a protest singer after all….

No, no, no. His earliest stuff showed a vague sympathy for black people and poor whites, but Dylan 101 is that the guy is fundamentally apolitical.

I don’t think that’s right. Blowin’ in the Wind and Masters of War are both antiwar songs. His Christian period was basically protest music too. He vacillated, but I don’t have any real doubt that he opposed Vietnam and would be willing to argue about it.

I’m a big fan rather than an unquestionable expert, but my impression is that he basically didn’t care about Vietnam and probably wouldn’t have been willing to argue about it. There are some lines in “Tombstone Blues” that might possibly be about the war, but he never sang about it explicitly and I don’t think he ever discussed it in an interview. In fact, I saw a Vietnam-era interview where he was asked about Joan Baez’s anti-war activities and had absolutely nothing to say about them.

Dylan rejected the protest singer label and politics in general very aggressively early on, as you can see with some of his interview tantrums in Don’t Look Back and his liner-notes refrain, “I tell you there are no politics.” He’s also downplayed the political content of his earliest work–I know he said something like, “Masters of War was not an anti-war song. I’ve always said that everyone has the right to defend himself. I was just talking about what President Eisenhower called the military-industrial complex.” Okay, there are a few glimpses of politics here and there in his later work, like Union Sundown and Neighborhood Bully, but overall he’s against it.

I think looking for programmatic statements — even anti-programmatic programmatic statements — in Dylan is probably a mistake. Just because he irritated reporters by refusing to take a stand on Vietnam doesn’t mean he wouldn’t irritate Johnny Cash by poking at him about it.

That being said, the dialogue could be made up for all I know. There aren’t any sources given, I don’t think.

People worship musicians because they communicate something. It’s not that every person who suffers is an artist, but every person who suffers, and is able to communicate their suffering so that other people feel it, too, is an artist.

And it’s no good pointing to musicians who write really banal lyrics and saying, those people don’t communicate anything, because the music itself can communicate emotion.

I more or less agree with your assessment of the book, Noah. Here was my take:

http://tinyurl.com/2f75o6w

Kleist’s book only skims the surface of Johnny Cash, the man, focusing instead on the “Man in Black” legend. Still, the artwork is excellent, and the inky style is particularly well-suited to its subject matter.

Subdee, communication in and of itself isn’t enough to explain it. After all, people communicate with each other all the time, but only sometimes does that turn into idolization. It has something to do with beauty, I think, and something to do with our particular (secular) culture.

Marc, that’s a nice review. Thanks for the link.

Dylan also admired Cash. He loved ‘I walk the Line’.

Dylan’s denial of politics had more to do with personal issues. When turned into a hero and “voice of a generation,” people chased him around, tried to worship him, and generally turned him into a “celebrity.” He tried to get away from that by denying the political affiliations, disappearing off the map at times, making radical shifts in his self-presentation (including away from folk music and protest music), etc. None of that really tells us much about what his politics supposedly were/are. I would note that he continued to sing many of his most protest-y songs even through to the present day. Masters of War, Times, etc. Even in the ’70’s, he was writing songs like Hurricane, which is certainly a political song.

I have no idea about the conversation with Cash, however.

I’m with subdee on this one. When we understand the artist and feel what they’re feeling, we feel understood ourselves, and that’s a deep human need. We end up thinking of them as some kind of beloved kin, because they say what we can’t articulate in a way that makes you feel it, and it’s validating and comforting and…well, that’s all I’ve got.

I bet Johnny Cash sang some song about the minstrel and his power. If he did, it was better than anything I could write.