Fashion, Fighting and Literature: Hana no Asuka-gumi

Sometimes, the power of a series is in the details. The subtle moments, the deft stroke of a brush or subtle camera-work, the sound of a voice catching at just the right moment.

In Hana no Asuka-gumi, the power of the series is in the grand scheme, the wide-angle view of a world that, whether it truly exists or not, will never be seen by those unaware of its existence.

We all know that in every great city, in every country, there is an underworld organization that runs the illicit businesses humans require. But what if there was, behind even that, another world, an even more obscure world, of gangs and drugs and phone texting competitions and boy bands – a world that extends through middle and high schools country-wide?

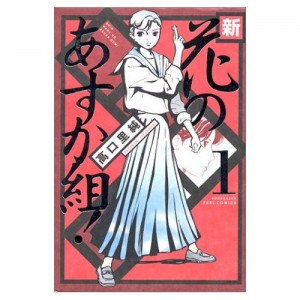

In Hana no Asuka-gumi, Asuka is both part of and an outsider to a pervasive underground organization that runs all the girl gangs of Tokyo. “Gumi” here means gang, so the translation can be “Asuka of the Flowers Gang.” However, the “Hana no” is most often translated as “Magnficent” as in the “Hana no Nijuuyo-nen Gumi,” the “Magnificent 49ers” the name used to loosely identify the mothers of girls’ manga in Japan. It would not be out of the pale to translate the series “The Magnificent Asuka Gang.”

Asuka was, despite her small size and age, before the series even begins, the second-most powerful person in this organization. The organization, known as the Zenchuu Ura, is run by the mysterious and charismatic Hibari-sama and closely resembles the organizational structure of the Imperial Court of Japan. Hibari-sama, veiled, curtained off from her court, is assisted by her Minister of the Left (Tactical) and Minister of the Right (Strategic.) As the story begins, Asuka has already left Hibari’s “court.” In the new series, one of her former body doubles has taken over as Minister of Left.

The gangs of Tokyo are arranged in 23 Wards, each with a Area Master, the daimyo of the organization, and there are four directional “Outside Groups.” Away from the direct influence of the Ministers and Area Masters is a group known as the Hibari SS, (nothing to do with the Nazi SS. It’s an Advisory Council that deals with non-gang projects like the Ranjuku Detention Center, fundraising through creation of Boy Band Mikoto 5 and…other projects.)

The series includes run-ins with the local “Business Group” – i.e., the local Yakuza gang, and other criminal types on the periphery of society. If this all feels a bit contrived and complicated then you can congratulate yourself on being sane. The series is indeed contrived, complicated and congested with characters.

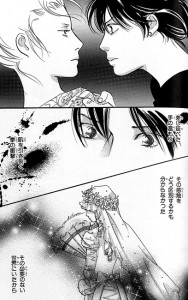

The original Hana no Asuka-gumi ran for 28 volumes, 6 supplementary volumes, and two novels, over 10 years, from 1986-1995. It ended with Asuka leaving Tokyo to go to America to get away from all this craziness. 18 years later in our time it picked back up – 4 months later in series time. Asuka has returned from America and with her return, everything explodes. Hibari-sama seeks to draw Asuka back into her clutches (literally, it’s well-established that Hibari-sama desires Asuka physically) and wants to punish her for not playing along. The new series ran for 8 volumes, from 2004-2009.

For all of the complexity, for all the longevity of the series, non of these are why I consider it “literature.” For that, I turn Umberto Eco who, in his book On Literature defines as Literature any written work that surpasses its original medium. Hana no Asuka-gumi did that when it was turned into two OVAs and a Drama CD. OVA is short for Original Video Animation. OVAs were straight-to-video (now, DVD) releases that bypass any Television or theatrical release. Drama CDs are voice-only performances of the story…and my particular fetish. My Hana no Asuka-gumi Drama CD is one of my prize obscure possessions, with a cast of amazingly talented voice actresses. Ogata Megumi voices Asuka perfectly while Soumi Yoko voices Hibari-sama, her voice dripping with sweet poison…. The series was also turned into a live-action TV show and a movie…and recently a second movie was made starring the manga creator’s own daughter as the lead character.

None of this why I consider it “literature.”

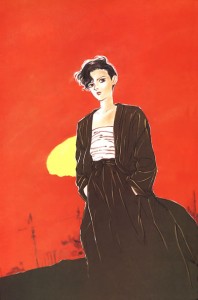

I consider it “Literature” because in an discussion with a Japanese friend who is my age, she mentioned that when the original series ran, it was *so* popular that girls on the streets of Tokyo started to dress like the characters in the book. When a manga affects popular fashion…now *that’s* Literature. Ichiko from Kamikaze Girls for instance, owes some of her bad-ass looks to Asuka. Sadly for teen fashion, when Asuka returned this century, Hibari-sama had succumbed to the lure of Goth-Loli and girl gang couture has not caught on again.

Hana no Asuka-gumi is over now – for good – but its spirit lives on everywhere gang girls with extra-long school uniform skirts, faces hidden by medical face masks and sarashi-bound chests can be found.

“defines as Literature any written work that surpasses its original medium.”

What a bizarre definition! That makes Twilight and Superman and anything that’s ever had a movie version into literature.

I like the idea that only those works which have influenced popular fashion count as literature. That would means the Beatles are literature but not John Updike. I can definitely live with that.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Overthinking Things 12/5/10 « The Hooded Utilitarian -- Topsy.com

This is why sweeping definitions of Literature frustrate me. Literature, for me, is sort of one’s personal mental “display shelf” – works that are so good, so deep, so impactful, so beautiful, so memorable and enjoyable, so innovative, so well-made that you want them to stare at you every time you wake up, or every time you walk into your office or studio.

For me, this includes some canon lit (Sinclair Lewis’ Arrowsmith, for example, and The Story of O, and Gravity’s Rainbow) as well as some speculative fiction (Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, William Gibson’s Neuromancer, The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. LeGuin), plenty of comics (Acme Novelty Library and, recently, Asterios Polyp), and plenty of movies and animation (Woman In The Dunes, the Ghost In The Shell franchise, the original Nosferatu and Metropolis).

The boundaries for this personal category are fuzzy and emotional. Clearly, we need communal, public definitions of what is good and worth reading, lionizing and celebrating – people would be lost in the sea of information without them – but doing so is such a messy and difficult business that it seems impossible to come up with such definitions that are fair, objective, and inclusive.

I don’t think it’s fair to popular taste and popular needs to completely dismiss popular works. I also don’t think it’s fair to intelligent people to assume that they’re all contained in the academy, or that their views would all be consistent with those prevalent in the academy (and the upmarket publications as well, New York Review of Books for example). However, the resources of known and respected Intelligent people we have are deeply important, and I have far too much respect for intelligence to classify as literature something which makes smart folks everywhere cry at the sheer, blinding awfulness of it, no matter how popular (Twilight, for example – although I’ll happily admit that Harry Potter is more than literary enough for me).

This sort of exercise is enough to get me running around in circles with my hands in the air. Storytelling and its relatives (poetry, the stuff in the Abstract Comics anthology, whatever Gravity’s Rainbow is) serve all sorts of different needs and can succeed or fail in all sorts of different ways. Need-specific judgment may be, in the end, more useful than the establishment of an overarching Canon of Literature. Clearly (to me, at least) the act of canon-making is a natural process, but a canon of feminist speculative fiction, or a canon of gothic fiction or experimental puzzle-narratives or bildungsromans, may be more useful (and more able to recognize the diverse needs of human beings) than The Canon, as artificial as those boundaries are. The Canon will probably continue to exist anyway, though, officially or not (so Harold Bloom can rest easy).

I’m not happy to turn the whole thing over to market-dictated popular taste. I’m not THAT anti-intellectual.

I DO have a pet interest in narratives about Japanese girl gangs, though, which is why I ended up bloviating in circles about Teh Literatchers on this post anyway.

tl;dr – An overarching Canon is of limited use, and is inherently biased towards those with intellectual power and station. The market is an even faultier indicator, though. Storytelling serves many needs, and canons geared to those various needs, while also flawed, are probably more useful than a big-C grand Canon of Literature. Also, Japanese girl gang stories are awesome.

Is there a whole genre of Japanese girl gang stories?

Also, I like Twilight. More than Sinclair Lewis, probably, but not as much as Ursula K. Le Guin.

While I would never presume to interpret for Umberto Eco, it has always seemed to me to be sensible to think that if a series (and its characters) is compelling enough to be turned into fan art, stories, novels, movies, etc, then it is indeed Literature – whether it is a popular series, a literary series or something else.

@Noah – There is not a specific named genre, but during the 80s, there were several insanely popular manga series: Hana no Asuka-gumi, Sukeban Deka (probably the one of the three best known on western shores) and YajiKita Gakuen Douchuuki.

Sukeban Deka was turned into an anime, and a series of insanely popular live-action TV series that passed the name Asamiya Saki down to next generations as if it were a title. (In one memorable episode of, I believe, the third Sukeban Deka TV series Saki fights a Darth Vader-like being. That was pretty great.) The series has also been turned into a number of movies, the most recent of which “Yo-yo Cop: Codename Asamiya Saki” was released here by Media Blasters – it’s damn good. Another nice bit of meta – the character of “Saki’s” mother is played by a woman who played Saki in the original TV series.

YajiKita is by its very nature a fanfic/meta-version of a piece of classic Japanese literature, as Yaji and Kita are characters from “Shank’s Mare,” the comedic Edo-period novel. Where the originals traveled from town to town being embroiled in idiot plots and getting taken for the fools they were, this Yaji and Kita are girls who travel from school to school (like Saki) and fight off the Yakuza and other underground organizations that have taken over the school. YajiKita Gakuen Douchuuki has a short anime and, like Hana no Asuka-gumi started up again 20 years after it stopped at 22 volumes of manga, ran another 8 or so volumes and wrapped up again.

I consider each one of these Literature, by my and Eco’s definitions. :-)

Hey Erica, great post. Could you maybe pinpoint the quote you’re talking about from “On Literature” (maybe on Google Books)?

I ask because that’s also the book where he says “Literary works … offer us a discourse that has many layers of reading and place before us the ambiguities of language and of real life” (p. 4), that they perform a “true educational function” (p. 13), and that one of literature’s “[principle functions] lies in … lessons about fate and death” (p. 15).

Not to suggest that any of that is contradictory with the bit you quote, but it’s so much more conventional. So I’m curious to compare (and the keyword search has failed me)…does he keep going and eventually end up refuting the definitions in the first chapter?

I love the idea of literature as a work that influences fashion, too.

I think I need this manga. It looks soooooo good. And I love the pictures of the girl gangs. Awesome!

@Caro – the book is a collection of essays and presentations over time, so he provides a number of perspectives. When I get a chance I’ll dig out the bitI was referring to.

@VM – It is so good. Absolutely cracktastic stuff.

HnA-g also has a special place in my life because long after the first series ended, but long before the new one began I wrote a fanfic for it. Three times in the new series, something happens that I had written about in that fanfic…and it’s not conventional stuff either. I wrote that a dead character was talking to Asuka in her head. When, in Volume 5 of the new series, she did, I actually ran around the house screaming “I KNEW IT!!!” or something equally as dignified.

I am WAY too stuffy to like Twilight more than Sinclair Lewis (or AT ALL, for that matter), and I have a hot pink mohawk. I’m much more in line with the Eco quote Caro brought up about literature providing multiple levels of reading and a glimpse of the ambiguities of life, etc. I think that it’s more complicated than that, I allow for a multi-layered approach with different types of work serving different needs (I’ve been known to watch Buffy and I do love me some vintage boys’ and girls’ manga), I will happily include some “genre” works in my personal canon and exclude various highbrow material, but the top tier of my favorites will almost always be occupied by works that satisfy Eco’s criteria in some capacity.

That’s not to say that I need or want all of my intake to consist of such material, or that I cannot appreciate, say, Plan 9 From Outer Space or Spaceballs, but Great Works for me usually have to resonate on some deep level, which involves ye olde ambiguity and multi-level reading. Usually.

Of course, there are other useful ways of reading a piece than looking for that sort of “literary power” in it, and there are works out there that try so hard for such power that they suffocate the reader in the process. A work which is completely unambiguous but personally relevant and incredibly crafty and funny may float my boat a great deal more than a try-hard ambiguous/multi-level-reading novel tailored for academic critics which is dry as sawdust. I may love a piece for its craft, or for its invention, or simply for its weirdness or unintentional humor. I LOVE Asterios Polyp, which is highly formally inventive, reads on multiple levels and is filled with puzzle-solving, schematic Ideas, artistry and all sorts of goodies, but is hardly what I’d call “ambiguous” at its core.

So again I get to this place where the traditional definition is useful, but doesn’t quite hold up.

I’m really reaching here.

Ultimately, I’ve got an internal emotional model – when I read or watch something, I have an intuitive sense of how it impacts me, what it means for me, where it sits in my personal universe of stories. All of this grasping at a coherent model of some kind only serves to hopefully make some tenuous sense of that process, not to replace (or even really supplement) it.

Alas, poorly written sparkling Mormon vampire stories have no place in my story-verse. Girl gangsters, on the other hand…

It’s entirely possible that my simultaneous love of works that strike me in a “literary” way and works that are shamelessly genre and simple great fun is weird or incongruous, but to me they just occupy different places in my life. That means that I wouldn’t really want to put Twilight up against Sinclair Lewis even if I *liked* Twilight. It’s a bit like comparing a wine to a steak – it doesn’t quite work.

I do love when those different itches are scratched by the same piece, though, especially if that multi-scratchular quality makes a poetic sort of internal sense for the work.

Bloooooviate! Bloooooooooviate!

It’s been a long time since I read Sinclair Lewis. I just found him simplistic and boring. Sneering at middle-class Americans — way to go out on a limb there. But there’s a lot of canonical literature I love. Stephen Crane’s a genius, for example.

Twilight isn’t that poorly written, I don’t think. Certainly no worse than Rowling. It’s politics aren’t any worse either. And it’s weirder and more perverse, which I appreciate.

Did you see the Asterios Polyp roundtable here?

Stephen Crane’s poetry is wonderful because it can be simultaneously blunt and ambiguous, which is quite a feat. It’s also quite often not beautiful, which is a refreshing change from the poetry of the time.

I feel like, in Arrowsmith at least (which is what I’ve read of his work), he significantly complicates the sneering-at-middle-class-Americans routine. I’ve heard that his earlier works are quite simplistic, though.

If I want weird and perverse, I don’t read YA vampire novels. That’s what Octave Mirbeau, Rampo Edogawa, Marquis de Sade, Pauline Reage, Jean Genet, William S. Burroughs, J.G. Ballard, Shintaro Kago, Maruo Suehiro and my own daily life are for.

I actually have a nice little shelf of such material; you could say I’m fond of it.

I haven’t read Twilight, like most of the people who trash it loudly on the Internet. You’ve gathered that already, right?

Still, no Mormon sparkle-pyres for me, thanks.

I did see the roundtable, as well as read critical reviews and discourse elsewhere on the Webs. I actually ingested a good deal of the less friendly Internets discourse on the book before I read it, which is surely inadvisable, but it in no way interfered with my ability to adore the book to no end.

Twilight’s weirder in a lot of ways than de Sade, and certainly than Ballard. I think it’s weirder than the Burroughs I’ve read too. Haven’t read enough of the others to say for sure. But, near as I can tell, in the present climate, sparkly Mormon vampires are a lot more controversial than sadism or evocations of atavism or avant garde prose. If you’re looking for perversion, there’s something to be said for repression.

Not that you should read it if you don’t want to. It’s not great or anything. It’s much odder and more interesting than most people give it credit for though.

Have any of you read Dave Barry’s parody of Twilight?

Ah, now I think I see where you’re going. In that light, I suppose a reading of Twilight might actually be interesting fun.

I’ve got to say, though, that I take issue with the idea that serious, edgeplay kink is in any way uncontroversial with the vast majority of the Earth’s populace, or even the majority of first-world citizens or Westerners, the prevalence of dangerously cheap made-in-China furry handcuffs aside. I think there’s a dark, absurd, embarrassing heart to the polymorphous perversion of the erotic imagination that discomforts and confuses the hell out of almost everyone.

It wouldn’t be such a constantly-hinted-at-but-never-spoken thing otherwise. Insofar as eroticism is everywhere, hinted at, implied, half-illustrated, blushed at, screamed about, and insofar as it all bleeds together at the center, much of humanity’s expressive activity seems to be taken up with dancing around the edges of polymorphous perversity. We get excited and uncomfortable when it’s there – see debates about porn, censorship, appropriate clothing, what should be shown to children or in movie theaters – and just as much when it’s not there – try to explain asexuality to people, and watch them get all flushed and confused.

Girl gang stories are great fun because they plug into that Erotic Imagination Thing in such an interesting way. Hell, maybe Twilight does too.

@Anja – You’ve hit the nail on the crumpet for me, at least. Asuka, Sukeban Deka and YajiKita indeed have that Erotic Imagination Thing. In Asuka, her love interest is another girl, a hoodlum and a sociopath who uses her in horrible ways, and of course Hibari-sama has practically fetishized the idea of Asuka to the point of obsession. There’s a guy whose in love with her toom, but no one takes Yasuhiro seriously, least of all, Asuka.

In YajiKita, Kita is the object of many a girl’s fantasy, while Yaji attracts boys, both pretty and petty. But they belong together in a partnership neither enjoys, but they can’t give up.

And in Sukeban Deka, Saki is hit on and adored by characters male and female throughout, but her true love is her mentor Jin. Jin’s a cool half-Japanese guy and much too old for Saki so nothing comes of it until they are both dead. But they are a great dead couple.

I love these series with all my Erotic Imagination Thing Love. ^_^

“much of humanity’s expressive activity seems to be taken up with dancing around the edges of polymorphous perversity.”

Not on the internet so much. Bucketfuls of explicitness wherever you want to point your browser…..

I take your point to some degree, but remain skeptical. If you have a few hours and want to see my more extended take on this, you could check out this project I edited some years back, which has various takes on the subversiveness/non-subversiveness/posibilities/limitations/etc. of the polymorphously perverse.

The one actual review of it I ever got was mostly cranky because I didn’t fully embrace the kink-is-subversive stance which is where I think you’re coming from. But anyway, you can browse around in it and see what you think.

Just to be a little clearer; I have sympathy for the kink is subversive stance too; I’m just really ambivalent about it. Ambivalence being my demographic destiny as middle-class wishy-washy liberal….

@Noah – I would argue that a good deal of that Internets explicitness is still dancing, excited-uncomfortable-wise, around polymorphous perversity, yelping about it frantically, diving in and running out to get a towel, dumping other people in without their consent, and generally doing everything other than calmly, happily immersing it and remembering to obey SSC/RACK and use proper protection.

Not that I really expect anything else, of course. An attitude that chill and mature around one of life’s primary founts of passionate emotion is a borderline-utopian tall order.

@Erica – There’s a great book you might enjoy called Behind The Pink Curtain: The Complete History of Japanese Sex Cinema, by Jasper Sharp. It’s detailed, annotated history of the pinku eiga (pink film), roman porno (romance porn) and related genres – erotic story-films, too sexy for regular theaters but not “porn” in the conventional sense, shown in a special network of seedy theaters across Japan. It’s a great story, filled with gangsters, 1960s Communist student revolutionaries, terrorism (yes, actual terrorism!) and exploitation of every kind: historical bondage, geisha and samurai films, topless pearl divers, yakuza, nuns, fallen pop stars, women in prison, student revolutionaries, train molesters, schoolgirls, girl gangsters, and general lewdness of every kind. A few remarkable directors have emerged from the field, including Koji Wakamatsu, Takahisa ZeZe and Mitsuru Meike.

In completely unrelated news, I just got Acme Novelty Library no. 20 and will be spending the next couple weeks recovering from reading it.

Anja, I can see why you’d want your kink to be safe and happy in real life. In imaginative representations, though…I don’t really see why nonconsensual or nonsafe or even frantic stories or dreams mean that people are avoiding the power and the glory of their ids. Anyway, if you want people talking about safe, happy kink in a mutually positive consensual relationship, I’m sure the internet has scads of it. If it’s porn, it’s out there.

I’m generally with Foucault on this; I don’t think there’s too little discussion of sex, of any kind.

Oh, that’s not what I meant at all! I didn’t mean that there’s too much consensual-nonconsent or extreme material. It’s just the attitudes I see in a lot of it… it’s like people have to stop being grown-ups the moment they start delving into the sexual id. There’s this sort of leering, drooling atmosphere around most of pornography and a lot of sexual imagery out there period. It’s what Sallie Tisdale calls “cultural puberty: lewd, leering, intensely curious and ashamed and prudish all at once.”

The places on our beautiful Internets I don’t find this sort of cultural-puberty glaze over things are niche sites devoted to kink-knowledgeable people, those in the community, and people involved some tiny, rare, specific fetish.

It’s like people have to pass through the Uncanny Valley of pubescent sexuality in order to come out the other side a calm grown-up about the whole thing, and as far as the Internets is concerned (not that I think it’s really representative), only electricity-play enthusiasts, balloon fetishists and creators/consumers of underground queer porn have as yet climbed up the other side.

Aaaanyway.

Foucault said that? Foucault, the inveterate kinkster?

For reals?

History of Sexuality is basically arguing that Freud got it backward; sexuality isn’t repressed and needs to be revealed through talking; rather, sexuality is manufactured and controlled through compulsive discussion of it. He thought kink should occur in silence. He’s really, really not Susie Bright.

I’m not convinced that being calm or grown-up about sexuality is necessarily something to strive for in either life or porn…but that’s me….

I’m quite convinced that being mature about and respectful of the erotic imagination in the same way that people generally are of the creative imagination is crucial to gender liberation, ending (real, non-kinky) sexual violence and coercion, validating and including sexually marginalized people, doing right by sex workers, alleviating body image problems, and all sorts of good, politically correct, gobsmackingly warm and fuzzy causes besides.

That doesn’t mean taking an unemotional attitude, but working on and maturing the emotions. I think that much better, more grown-up – and no less free and fun – sexual culture is possible, much more respectful and productive than the one we’ve got. I say this especially as a transgender person who’s sick of “she-male” tropes being the loudest consistent cultural voice on what trans people are. Porn means that transmen and genderqueer/genderfluid folks are invisible or marginal (with the sole exception of Buck Angel), while transwomen are portrayed as extreme reifications of patriarchal, heterosexist ideas of what female sexuality is or ought to be, shaped into a sort of third-genderedness that binary transwomen don’t want but that nonbinary trans/genderqueer people are denied by way of invisibility.

Also, kink is either full of communication or is simply unsafe. I’ve not read Foucault, but if he thought otherwise, he was naive and wrong (like he was in his politics, maybe?). Kink in silence can be wonderful, but if “silence” means “absence of language,” and “language” includes body language, safe signals, subverbal cues, etc., then I’m glad I never played with the guy (not that he would’ve been interested in me).

One thing I don’t get is how silent, or even wholly noncommunicative, kink would somehow escape the all-powerful shaping hand of discourse and power which he was so fond of finding under beds, stashed in closets, hiding in the rafters, clogging the pipes and wedged under people’s fingernails. Isn’t the kinky desire being acted upon in silence itself a product of discourse and power?

I’m not Susie Bright either, thank goodness. I don’t think I could handle being her.

I might be able to handle being Patrick Califia…

What exactly Foucault is advocating is hard to say. His politics may have been wrong, but I don’t think you can say they were naive. He thought abstract concepts like justice and freedom were cloaks for power. I think he’d probably say the same about safe consensual kink; he’d see it not as liberating but as a way to tame and control bodies and pleasures. Or at least that’s my sense of him. He was pretty radically antihumanist.

Is being mature and respectful of the erotic imagination the same as having mature and respectful imaginative representations of kink, though? You brought up de Sade and Ballard; neither of them is particularly mature or respectful, are they?

Yeah. I find Foucault interesting, at the very least because of his stature as a queer intellectual icon, but I’m afraid I’m pretty radically not much of a radical antihumanist.

Being mature and respectful -of- the erotic imagination is not the same thing as constraining one’s erotic imaginings to be “mature and respectful” (i.e., dead). De Sade certainly wasn’t mature and respectful in any sense, but I still enjoy his work; Ballard, maybe, maybe not. Neither engaged in the sort of puerile idiocy that’s so rife now, though, even if de Sade may have at times gotten close.