A Single Match is an anthology of short stories by Oji Suzuki published by Drawn and Quarterly. This is a review of the title story. The pages read from left to right.

“I had just seen, standing a little way back from the hog’s-back road long which we were traveling, three trees which probably marked the entry to a covered driveway and formed a pattern which I was not seeing for the first time…Where had I looked at them before? …Was I to suppose, then, that they came from years already so remote in my life that the landscape which surrounded them had been entirely obliterated from my memory…?…Were they not rather to be numbered among those dream landscapes, always the same, at least for me in whom their strange aspect was only the objectivation in my sleeping mind of the effort I made while awake either to penetrate the mystery of a place beneath the outward appearance of which I was dimly conscious of there being something more…Or were they merely an image freshly extracted from a dream of the night before, but already so worn, so faded that it seemed to me to come from somewhere far more distant?”

In Search of Lost Time, Marcel Proust

Where this story begins and ends is simple yet ambiguous.

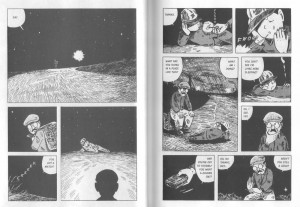

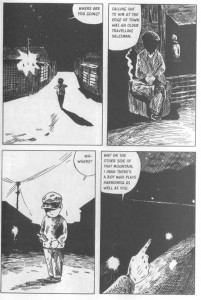

A middle-aged salesman is making his way down a country road when a young boy asks him for a match. The salesman supplies this readily; the match is lit, and he sits down for a rest and a fag with the boy.

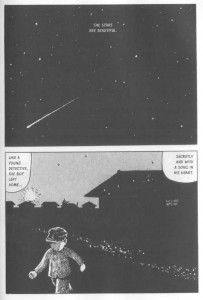

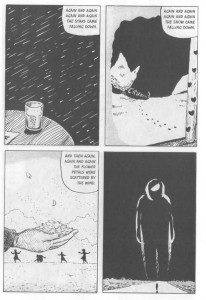

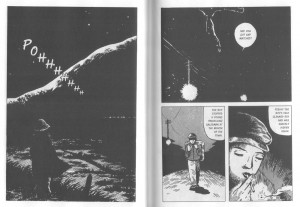

A shooting star streaks across the night sky like a flint strike.

An age and half a thought ago, and another boy is moving through the darkness like a “detective” in search of a life already led. On the face of things, he would appear to be the old salesman at the beginning of his journey through life, a premise which proves progressively more intricate the further we venture into Suzuki’s tale.

Suzuki’s conception of memory here is of a waking dream without beginning or end. The boy is a traveler in search of old, familiar memories; …

…these reminiscences not viewed as a cadaverous past fixed in amber but a world of possibilities slowly rediscovered; circuitous, mangled, confused, and yet real.

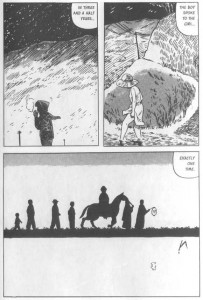

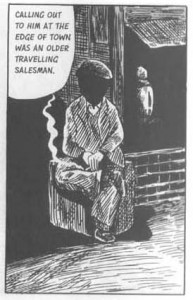

The “older traveling salesman” the boy meets at the edge of town is fully illuminated except for his face, a stranger to us on our first reading, but then perceived as a shade of his older self on our reattendance.

He gives the boy directions to an isolated farmstead and another boy who used to play the harmonica as well as he does.

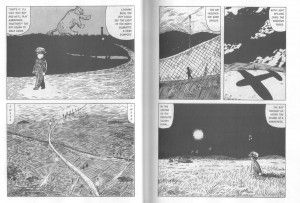

His guiding light is the single match struck at the beginning of the tale. A stuffed bear sits on the horizon like a constellation and the shadow of an airplane obscures familiar fields and byways; all these recurring images in the comics of the artist, and reiterated throughout the anthology both directly and tangentially in the form of curios and strangely reduced objects.

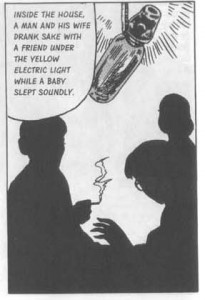

The boy finds the house is in the middle of the “Suzuki plain”. There is the sound of a harmonica playing as he approaches at a distance but only silence when he reaches the front gate. A couple is attending to a baby and he is greeted warmly by figures who remain indistinct despite the glare of an electric light.

He is given bread and information: the boy passed by that house a long time ago. In return, he leaves his harmonica in the couple’s mailbox, a token to his younger self and the songs he left behind. The rest is mystery, the darkness between points of remembrance.

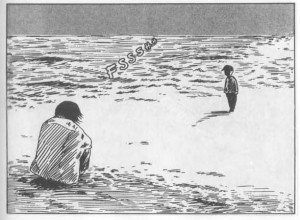

The boy is grasping for an image fully known yet out of reach. Just like the woman which he encounters on a beach, seemingly youthful when seen from behind…

…then blind, senile and covered in sand as we look her full in the face.

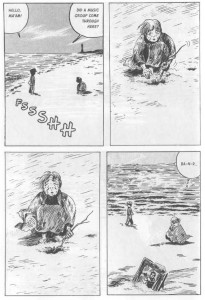

Another time, another memory, and the moment before a match is struck.

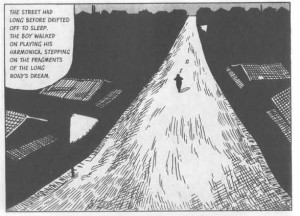

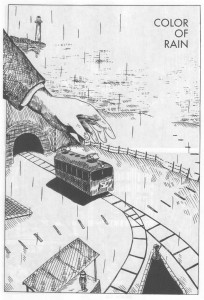

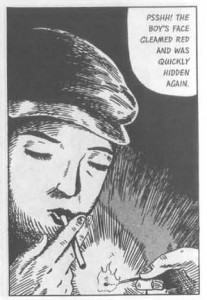

The man begins to remember his first love; her image retained though the most affectionate of gestures: a young girl’s “fearful way” of striking a match. When the editors of the anthology allude to the “elliptical” nature of Suzuki’s stories they mean to evoke not only the shape of these stories but also the spaces which fill the narrative; their labyrinthine form, the chronological jumps between pages and the gaps in logical sense between panels.

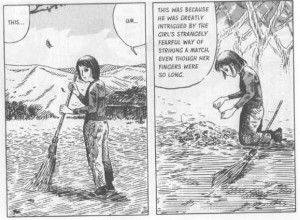

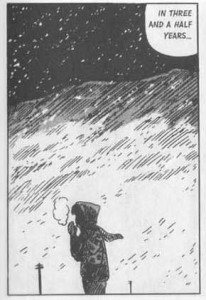

The images which close this three page sequence are presented with a minimum of narration. Everything is suggested by a simple statement of times past: “In three and a half years…the boy spoke to the girl…exactly one time”.

Three and a half years: a winter chill; …

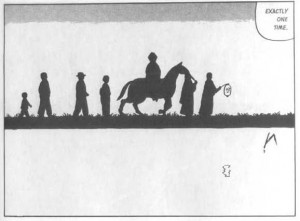

…a summer breeze; …

…an autumn festival (a wedding procession?) presaging the raking and burning of leaves.

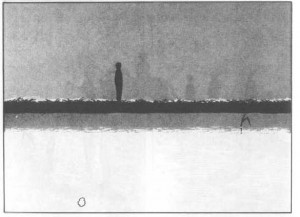

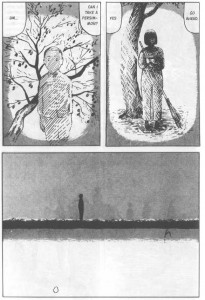

The boy first seen in silent harmony, then alone on the page following. A faint glow (a disembodied memory) is reflected in the river; soon to be left behind at the left trailing edge of the panel.

The faces of the boy and girl are barely discernible during their first and only conversation. The inked is scraped from their forms, the emotions uncertain from the imagery yet all too evident from the collage of recollections.

The seasons pass in a single page. The stars reflect his memories; the roads become familiar, dull and treacherous.

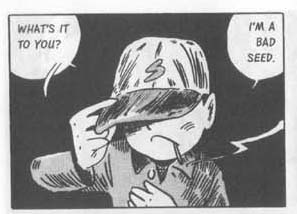

He is back where he began; indiscernible to us except in an ageless silhouette, still a boy if only in his mind. He stops “a young traveling salesman” at the mouth of a town; a figure which looks all too familiar, the man who gave him directions at the start of his journey so many years ago.

[The boy meets a familiar figure]

[From an earlier encounter]

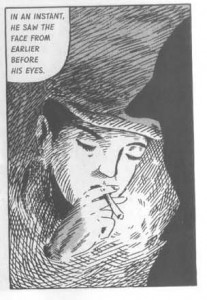

A vision of his younger self traveling the paths of memory, suddenly seen in luminous detail by the glow of a single matchstick now that he is “bent” down with years of remembering.

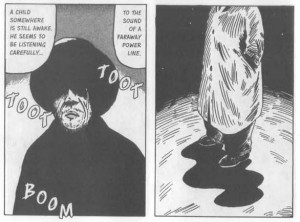

In the background, he has the vague inkling that another boy sits beside him, “still awake” and “listening carefully to the sound of a faraway power line”; the boy who he met at the start of his tale who now appears less abstruse, less curious, and less separate from himself.

* * *

Suzuki’s mingling of reality, memory, and fiction follows a tradition which can be traced back two thousand years to Zhuangzi’s butterfly dream; a theme further elaborated in the literature of 17th century China where we find a story in Pu Songling’s Liaozhai Zhiyi titled, “Sequel to a Dream”. A simple synopsis follows.

Having passed the imperial examinations, a man named, Juren Zeng, accompanies some of his comrades to consult an oracle about his future prospects. He is informed that he will be appointed Prime Minister and govern for “twenty peaceful years.” Zeng is pleased by this pronouncement but is suddenly caught in a drizzle on his way home, forcing him to take shelter in a monk’s chamber. Here a monk sits in meditation ignoring the intruding men. Zeng isn’t pleased by this behavior but decides to lie down to rest in view of his fatigue.

Moments later, he is approached by two eunuchs carrying a summons from the emperor. Once at the palace, he quickly rises to the high ministerial position foretold by the oracle, and manages to dispense kindness and evil in equal measure to his past acquaintances, indulging himself as his heart leads him.

Years pass and Zeng’s influence wanes. Following accusations of corruption, he is sent into exile in Yunnan. He encounters some bandits during this journey and is decapitated due to his belligerence. This is merely the start of his troubles. Zeng soon finds himself in hell and is tortured by the demons residing therein. He is then reincarnated as a baby girl belonging to a family of beggars. After several years of hardship, she is sold as a concubine to a scholar’s family which proceeds to ill treat her. When her husband is killed by some thieves, she is accused of his murder, tortured to extract a confession, and then sentenced to death. Zeng’s cries of injustice at this are heard by his companions who awake him from his nightmare.

As with Zhuangzi’s butterfly dream, this tale represents not only an examination of dharma but also an inquiry into the borders of reality. As Judith T. Zeitlin states in Historian of the Strange:

“I believe that it may be possible to see in the writings of a number of 17th century authors, commentators, and publishers and attempt to work out a new understanding of fiction and drama as a special sort of discourse with its own rules and properties. One of the chief attractions of the dream for writers like Pu Songling and his contemporaries was that it allowed them to explore their interest in the paradoxical nature of fiction — If fiction, like dream, is by definition “illusory,” “unreal”, in what sense may it be understood to exist?”

Suzuki’s “A Single Match” is just such an exploration but even more than this, a reverie where dreams and fiction are as real as memories, perhaps as real as life itself. Hence the figures in the “narrator’s” dream are etched and shaded to give the illusion of life, …

…while the storytellers which began the tale are delineated in a more cartoonish fashion.

The mysteries in Suzuki’s story resist sentimentality, the weaving and layering of images forestall the tedium of a mere recitation of biographical detail. This involuntary memory which in Proust was triggered by smell, taste and texture is for the protagonist of the manga elicited by sight, inanimate sounds and the spoken word: a request for a cigarette light; the myriad stars which seem like match flames; the lamps which flicker over streets and conversations…

….before fading and trickling into the night sky; a world of darkness filled with the periodic illumination of recollection; a magical evocation of remembrance at once strange, meaningful and “true”.

NOTES

Pingback: Tweets that mention Oji Suzuki’s “A Single Match” « The Hooded Utilitarian -- Topsy.com

Suat, so was this released recently? And was it just flipped, or did they do their reconstruction thing? And why are they still Westernizing the sequence anyway?

Yup, this was just released in January 2011 I think. Very little publicity from both the publisher and the usual blogs at present, but this might be due to the recent release. Most of what’s online is publisher’s ad copy.

I’m going to presume that D&Q flip their manga because their retail sales are mainly through book stores and the target audience is not your typical manga reader(?). I presume they’ve done the usual market research. On the other hand, they might just have a very low opinion of their customers.

I honestly can’t blame them – my prediction is that the book will sell badly (it’s a “tough” read from a manga perspective). I say this despite my opinion that this collection is in many ways superior to the recent Moto Hagio one in terms of artistic value. At least, many of the stories don’t need any special pleading from historical context to appreciate.

Okay, now you’re just trying to make me mad….

Huh? You didn’t like most of the Moto Hagio book yourself so it’s hardly some sort of high bar as far as you’re concerned.

Or are you expressing outrage at D&Q?

Thanks for writing about this Suat. I’ve been curious about it, but have seen nothing about it at all. I saw some of the artist’s work at that Garo show that was up in NYC last year, and it did look interesting.

Nah, I was teasing. I like the Moto Hagio stories I like a whole lot, even if some of the rest aren’t so hot….

Pingback: Links: The “Obamacare” Comic

What Noah was asking was whether D & Q has simply mirror-reversed the entire page, or whether it has left the panels unflipped but rearranged them on the page to make it read from left to right, as they did with the Tatsumi collections and Red Colored Elegy.

I’d like to know too, because if it’s the latter I’m not buying it. (Though, to be honest, I might not buy it anyway.)

Yeah, I know what he was asking but I’m in no position to comment definitively since I don’t have the originals. If you listen to Sean, the answer would be be “yes” (I think he’s of the opinion that D&Q do it to all their manga). Actually, Adam, you would be in a far better position than me to make the determination in view of your access to the material and command of the language. Some of the books do appear to be long out of print from the websites above though.

To use an example from the movies: Antonioni’s Red Desert was for years only available in a terrible DVD (which went for multiples of its retail price). If you wanted to see the film outwith the film societies, you would have had to make do with that copy. I would say the same applies to the manga above for readers who can’t read Japanese. I doubt if any one would be foolish enough to publish such a non-commercial book in the near future. Tatsumi is definitely the safer bet for American publishers. His middle-of-the-road stories would appear to sell well even though he’s a far less interesting manga artist in my view.

Pingback: New manga, old manga, vintage manga, overpriced manga? « MangaBlog

Suzuki would probably do with a bump from some American cartoonist, the way Tatsumi did from Tomine.

There should be an “adopt an obscure Japanese manga-ka” program. (Though, come to think of it, isn’t there a Chris Ware designed manga book coming out soon from… someone…)

Actually I don’t have any more access than anyone who lives near or regularly visits a city with a Japanese bookstore. And of course you don’t need to know Japanese to tell if a panel has been flipped or not.

Obviously, for those who don’t know Japanese, this collection is their only means of access to Suzuki. For many of the stories, it’s probably the only means of access for those who do know Japanese. And if the book looked indispensible, I’d grit my teeth and buy it. But from what you show it doesn’t, although Suzuki is a good artist.

Finally, I’m not sure why you’re so pessimistic about the future of non-commercial manga. There are several publishers aside from D & Q publishing “art manga,” some of which (e. g. Yuichi Yokoyama) is a lot less commercial than this book. And none of these other publishers find it necessary to do what D & Q does. In any case, as I’ve said before, it’s not the fact that D & Q’s books read left-to-right that I mind so much; it’s the cut-and-paste job they do.