This essay first appeared on Splice Today.

_____________________________________

In D. H. Lawrence’s short story, “The Border Line,” Katherine Farquhar travels back to her native town on the French/German border while musing about her manly and unyielding ex-husband Alan, who died in the war. At the beginning of her journey she thinks of Philip, her second, insistently yielding husband as a better catch, since Alan was “too proud and unforgiving.” But over the course of the trip she begins to wonder…and finally at a train stop along the way Alan’s spirit comes to her and claims her. She swoons before him and becomes a true woman to his true man:

Now she knew it, and she submitted. Now that she was walking with a man who came from the halls of death, to her, for her relief. The strong, silent kindliness of him towards her, even now, was able to wipe out the ashy, nervous horror of the world from her body.

Soon Katherine learns to despise Philip, sneering at him as she looks to catch glimpses of her spirit lover and/or of various phallic symbols that Lawrence thoughtfully places in her way. For example, there’s the

great round fir-trunk that stood so alive and potent, so physical, bristling all its vast drooping greenness above the snow. She could feel him, Alan, in the trees’ potent presence. She wanted to go and press herself against the trunk.

Inevitably, beside such hard, straight thrusting, Philip’s potency flags. He becomes whiny, then ill, and then mortally ill. On his deathbed, he reaches out to Katherine, but Alan’s spirit comes in, his bits swinging beneath a kilt. He pulls Katherine away as Philip ignominiously expires. Then the true man makes necrolove to her “in the silent passion of a husband come back from a very long journey.”

_____________________

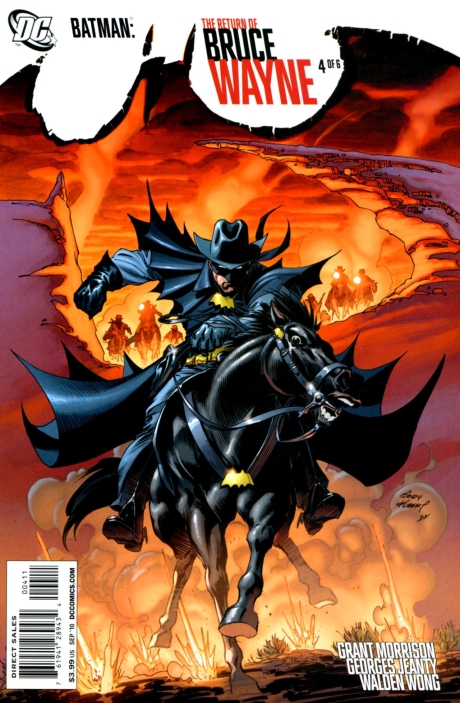

Grant Morrison’s Batman: The Return of Bruce Wayne also revolves around death, journeys, and mastery. Batman/Bruce Wayne is killed, but not really killed; instead he’s sent back in time. Robbed of his memory, he has to travel through the ages to his own era — except that the villainous Darkseid has rigged things so that when Batman gets back to the present the world will end. The superhero’s return from death is an event of such supreme awesomeness that it causes the apocalypse — except, of course (spoiler!) Batman figures out a way to save the world. Phew!

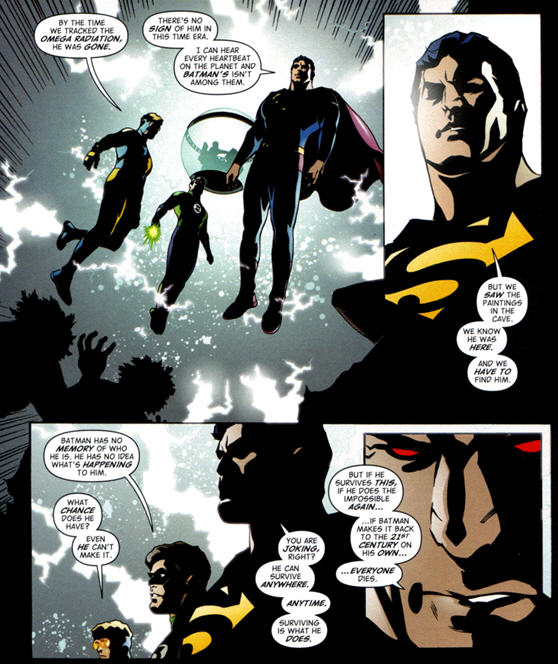

As the above paragraphs indicate, there’s something more than a little ridiculous about both the Lawrence story and the Morrison story arc. They both seem to be trying a little, or a lot, too hard — with “too hard” having the obvious Freudian implications, at least in Lawrence’s case. There’s something farcically desperate about the insistence that time and death are no barrier to the truly masterful man, whether wearing a kilt or a cowl. One of the most over-carbonated moments in The Return of Bruce Wayne occurs when the minor super-hero Booster Gold dares to question Batman’s absolute competence, and is immediately slapped down by a face-shadowed, sententious Superman:

Green Lantern: Batman has no memory of who he is. He has no idea what’s happening to him.

Booster Gold: What chance does he have? Even he can’t make it.

Superman: You are joking right? He can survive anywhere. Anytime. Surviving is what he does.

As Superman’s hagiographic paean suggests, there’s something of love in Morrison’s relationship with Batman. That fits with Lawrence’s story, in which there’s little doubt that the author is enamored with Alan’s potency. And by enamored, I mean in the precise sense, as a lover. Lawrence doesn’t so much want to be Alan as he wants to be with Alan; the story is told from Katherine’s point of view, and Alan is a mysterious, unspeaking spectral figure. In some sense he’s Lawrence’s avatar, penetrating the diegesis and the women in one fell swoop. But in another sense, he’s as inaccessible to Lawrence as to Katherine; both of them know him only when he enters them as lover. The power fantasy isn’t to be the master but to be the one mastered.

Batman’s not as unknowable as Alan, exactly — the text shifts in and out of his amnesiac consciousness. But the storytelling is so fractured (with art by fully a dozen artists) we never really get much of a sense of who Batman is as a person except through his amazing feats — the superhero substitute for Alan’s sexual oomph. Even those feats are often presented as an aura more than as specifics. When a possessed Batman beats the Justice League, we don’t even see much of the fight; it’s just assumed that he’s so cool he can obviously whip Starfire, so we don’t need to see how he’s doing it.

Before Lawrence, most romances were interested in showing courtship and love; Lawrence shears all that away so he can get to the good bits; i.e. power. Similarly, old superhero comics were interested in the mechanics of the fights and how the good guys defeated the bad guys. Morrison downplays that in order to emphasize the totality of Bat competence. We’re not with Batman as he figures things out or struggles to overcome the odds, the way we’re with Spider-Man in classic Lee/Ditko stories. Instead, we’re outside, looking on with awe as he outthinks Darkseid and Wonder Woman and Superman and everyone else who happens by. If this is an adolescent power fantasy, it’s not of being Batman but of being swept away by him.

Maybe. Sort of. More or less. The fact is, it’s difficult to figure out what exactly you’re supposed to feel or get out of The Return of Bruce Wayne. That’s because the book’s a sprawling mess. Lawrence’s story is elegant in its monomania; love of masterful potency runs through it as straight and rigid as that phallic tree. Morrison doesn’t trade in such universal symbols. Instead, his book is stitched together with semi-obscure ingroup icons. Bats, of course, pop up all over the place, and bells ringing, because in a mini-series several decades ago Frank Miller had Bruce Wayne ring a bell to summon Alfred to tell him that he planned to become a bat to fight criminals. And then there’s random cameos by old comics heroes like Jonah Hex and the Black Pirate and cameos by old comics villains like Vandal Savage, and then the historical Blackbeard shows up and a Cthulhu monster and of course Kirby’s New Gods walk on and Rip Hunter and Thomas Wayne, Bruce’s dad, who wore a bat costume at one point (which I knew) and seems to be some sort of evil witch doctor which maybe is canon now and I missed it? All in all, I could barely follow the story for all the intertextual comics references and fan service fan scruff — and I’ve been reading comics for three decades, and write about them professionally. There’s no doubt that, in terms of comics knowledge, I’m the whining Philip to Morrison’s all-powerful Alan. Hell, Morrison’s even Scottish. Maybe he has a kilt.

For Lawrence, mastery is maleness. You’d think that would be the case for a Batman story as well; this is pulp fiction for men, after all. But something else seems to be going on. Morrison doesn’t fetishize Batman’s manliness; he fetishizes his Batmanliness. Superman talks lovingly about Bruce’s Supersurvival skills — but what’s Superman doing there in the first place? He’s a deus ex machina that does nothing but sit there being Superman, just like Metron wanders on just to be Metron and Jonah Hex is there mostly just to be Jonah Hex. Morrison’s love is directed not so much at Batman as at the whole sprawling history of Batman comics. All the stupid minor DC characters, the incredibly, numbingly intricate, revised and re-revised origin stories, even the silly sound effects from the Batman TV show — that’s where Morrison’s heart is at. What maleness is for Lawrence, seventy-odd years of interconnected pulp backstory is to Morrison — the mystical heart of the world, which he kisses in fealty and grasps in a bid for mastery. “Whatever they [superheroes] touch turns to myth.” Morrison writes, and he seems to believe it.

The only problem is…this costumed genre clusterfuck? Mythic? It’s certainly not as mythic as Lawrence’s desperate love affair with manliness. Worshipping your dick isn’t ideal, but it has at least the virtue of being soul-killing and evil. Worshipping longboxes full of back issues, though, just suggests that you’re really confused.

Alan’s spirit making love to Katherine reminds me of a vampire in several earlier (’80’s or ’90’s) Anne Rice books. Actually, I think this might be a part of the common vampire lore, which is all about sex, forbidden attraction, and power. There might even be a name for it–have you heard of this? A vampire, in an invisible state, makes love to a human woman?

Simple. Put the Dick Back in Grayson

Or pull out. Or whatever

Abortion is mean / let a febus live / feed it to your kid

Hey Christina!

I think you’re right that it’s a not uncommon vampire trope (more or less.) And just in general as a fantasy the invisible lover is definitely something I’ve seen done before. I don’t know that there’s a particular name for it though….

Fandom circles sometimes refer to this as fucking on the astral plane, but I doubt that’s what lit-crit calls it. Heh.

I may be remembering it wrong, but I think that trope is used in Carmilla, one of the first European vamp stories (about women, btw!).

Man, I went to a few blog annotations of Bruce Wayne and still couldn’t make heads or tails of it. All the other heroes keep repeating how great Batman is at getting out of traps, but his ingenuity has shit to do with the eclipses that push him forward through time. And then the solution to this metaphysical caper is that he has to die again due to some 5th dimension Venom like costume that he wears after returning from the end of time. Fuck this crap. No more superhero books from Morrison. If I need annotations, then I’m going to read Kant, not some DC comic book.

Yeah…he’s lost his way in fairly spectacular fashon, has Grant. A real shame. That’s what you get for hanging out with Geoff Jones though, I guess…

“Worshipping longboxes full of back issues, though, just suggests that you’re really confused. ”

Morrison is willing to take the piss out of superheros from time to time, with the zombie Batman or the clone Batman’s and whatnot. It’s like he vacillates from “Superheroes are crap and I am like, so above this!” to “Superheroes are the true religion, descended from the myths of old!” That tired cliche is witnessed in this miniseries, with the cave man story which seems to be saying, when man first evolved to create the first totems, they were deities that now exist in the form of today’s comics. (Never read beyond issue 2, so I can’t put it in any context)

One could almost imagine Morrison is just cynically pandering to his audience in search of an easy buck.

An audience that repeatedly wants to be told, apparently, that their obsession with big media cartoon characters is very sacred, deep and important.

I don’t think he’s cynically pandering… I don’t think he ever is really taking the piss out of super-heroes exactly. Affectionately ribbing them maybe. Parodies are kind of part of the super-hero thing, and Morrison probably gets that.

This was a fascinating read, in a grad-school sort of way. Isn’t Grant Morrison supposed to be a lunatic? I’m not sure. My knowledge of superheroes doesn’t stray far beyond my boyfriend summarizing X-Men storylines from the ’80s, especially the ones where Dazzler fights the Hulk with prison lesbians or something.

Superman and Batman sittin’ in a tree… etc.

“Affectionately ribbing them maybe. Parodies are kind of part of the super-hero thing, and Morrison probably gets that.”

Hmmm, I guess it depends on how much you want to make of lines like “That’s all Batman is now- a brand, a logo, an idea gone past its sell by date”

A line frorm the Red Hood arc- he throws stuff like that in from time to time.

I recall, Morrison actually made John Bryne furious over some bits in New X-men making fun of the X-men costumes. I remember Bryne posting on his web site about how, in the superhero universe, the costumes were the equivalent of athletic costumes worn at the olympics, nobody should ever think they were funny in a non parody book, and fans who like Morrison are all full of self loathing.

I actually remember Morrison being sort of controversial among X-men fans on the internet back when he was writing that book, but now I don’t get that sense at all with his DC stuff. Everyone seems to eat up the “swooning at the sight of Batman’s awesomeness” bits, while not being offended at the gay jokes, and marketing jokes, or whatever.

The “Batman is so AWESOME!” scenes Morrison writes are trite formula stuff, so I guess I’m inclined to see it as pandering when I think about it, but I guess if Morrison is squeeing along with his audience, it isn’t pandering.

That’s pretty interesting. I see where you’re coming from; in his JLA run, the villains often had kind of the best lines — a lot of stuff about how the JLA were pompous stuffed suits, more or less. I liked that about it — that there was an articulation of why the characters were stupid and kind of intolerable, even if the genre formula always had to play out in the end. And Animal Man and Doom Patrol were kind of deconstructions of super-heroes in their way; both about marginal super-heroes, essentially, and how things looked somewhat different on the periphery. Not exactly critiques, but different perspectives.

I guess my feeling is that he used to have more of an edge…but fannishness was always a big part of where he was coming from. So his skepticism always, but more and more these days, ends up being used in the service of the fannishness — Batman always wins as a trope so ridiculous that it gets used against him…but then Batman’s even more cool than that and he still wins even when he’s going against the trope. Or the marketing jokes being actually part of the mythos. Or what have you.

Alan Moore’s an interesting contrast; somebody who certainly has fan impulses in him, but who started on the margins and sort of went further away. And even as early as something like Miracleman, the fannishness fueled the critique rather than the other way round. Even in Morrison’s most idiosyncratic work, like the Invisibles, I don’t think he’s ever really willing to suggest that the heroes are really maybe a bad idea the way Morrison does with some frequency.

Actually–Invisibles does have quite a bit of an interrogation of heroism–insofar as everyone’s a double or triple-agent, making it impossible to really sort out hero from villain.

Return of Bruce Wayne was really an unmitigated disaster from beginning to end, for the most part (I kind of vaguely remember liking one of the issues in the miniseries and thinking, “Ah, things are turning around!”–Then it got worse.

The new “Batman Incorporated” is enjoyable (after two issues)– as it seems free of the kind of hagiography and self-importance of “The Return” storyline. Morrison’s record on the Batman books tells me that it will eventually decline, though. He seems like he’s decent with beginnings of these superhero arcs, but the closer one gets to the hero’s inevitable victory the more masturbatory praise of Batman (or heroism in general) sinks in. One of these days, I’ll learn to give up.

Sadly, the story in Joe the Barbarian isn’t much better–but the art is beautiful.

The Invisibles has villains who turn out to be heroes (more or less.) He never really makes the case that the heroes are villains, or that the concept of superheroes is in itself morally problematic the way Moore has routinely in his superhero books. At least, that was my impression (there is that one story from the perspective of the villain shot by King Mob…that may be the closest he comes.)

I really enjoy the thematic of emo-boy deferred sadism versus a celebration of force that ends up being masochistic at its core.

Any thoughts on how that relates to V For Vendetta? I haven’t read the comic in forever, but really hated the movie– not for the point it tried to make, but for disavowing the point it seemed to me to really be making. The dictator, to me, stayed alive by learning how to pander to the cosmopolitan libertarian-anarchist-democratic aspirations required for a more modern puppet regime (the kind of cynical conservatism, incidentally, that I think is much more explicit in the Dark Knight movie).

V’s interesting. I think there is some of the mastery/desire to be mastered switching going on. We identify with Evie who is abused/used by V. And there’s masochistic hints of gender reversal too; undermining the big daddy by feminizing him, but then the undermining is in the interest of another indistiguishable daddy….

I’d say that V works similar to some Morrison work; there’s a discourse of revolution which is well-articulated and calls some of the super-hero tropes in question — but those are ultimately folded back into a superhero victory. The undermining is used to reify the tropes it’s supposed to be undermining. In Lawrence the worship of force ends up as a kind of wish to be weak; in V the attack on force ends up as an adolescent power fantasy.

I think Moore got smarter about this over time, though; Morrison’s gotten dumber.

Lawrence also was sometimes aware of his own dynamic too. There’s at least one story in the collection I read where the desire for mastery explicitly leads to absolute isolation and death. That is, the masochistic fantasy is deployed as a critique, rather than as a guilty, repressed excuse….

In Simone Weill’s essay on the Iliad she talks about force making a human into a thing, which is certainly the omnipotent view of ceaselessly inflicting pain, the viewpoint that Moore ends up ultimately subscribing to in the stories of his that I know– Watchmen being the one I have the most familiarity with. There is a Last Judgment, but it’s basically a hoax. Power exercises itself both glacially and catastrophically, but in no way can be touched by time.

I don’t think it’s right to say that Moore subscribes to the idea that humans are things, or that omnipotent force ceaselessly inflicts pain…. The last judgment is a hoax…but not just because someone planned it. It’s a hoax in part despite Adrian, because it’s not last (nothing ever ends….) Adrien’s effort to control the universe — to be the omnipotent force — is seen as ultimately futile, and likely to be washed away by eternity and chance (he’s called Ozymandias, after all.)

Well, except for our respective takes on Moore, I don’t think we disagree. Power turns its wielders into objects just as much as its victims (shades of Foucault), just as the monument of Shelley’s Ozymandias is reduced to a great stone leg. There’s something Viking-like about that view- there is glory and chaos, but fundamentally, endless war. Pretenders to omnipotence are just more victims. The false modesty of the dictator is actually a part of his rapture– the endless repetition of destruction and torture required to feed the unslakeable euphoria of power lust is a constant signification of death. But the rapture of the bolt thrower is still different from the rapture of the author or monk who must assert himself through continuously annihilating himself.

Yeah; the D.H. Lawrence story I was talking about (“The Island” I think? Or maybe “The Man Who Loved Islands”? ) makes that point; the need to control ultimately renders the protagonist beyond love or human feeling, which ends by making him dead.

It’s a pretty great story….

About V: Moore himself notes that he was quite careful not to take sides too overtly. He opposes Fascism and Anarchism while being careful to note the arguments for and against each side. V is nominally the hero, but he’s also a murderous, torturing bastard.

Anyone else notice how popular V masks have become at demonstrations? Even the Tea Party has adopted them.

I don’t think Moore really sells the ambivalence in the book, whatever he says in interviews…..

We’ve had the V debate before—I think the ambivalent is actually quite clear in the book. 1) V’s torture of Evey can’t help but be taken as problematic. 2) V basically takes over for Susan, manipulating all events, watching everyone with his TV cameras, etc. He becomes the fascist that he’s aiming to destroy. 3) There are several episodes (both early and late) that explicitly link V with Susan (the “Versions” chapter)–and V’s repeated comments about “bedding” Susan’s lady (Fate), and how Susan stole his (Justice). 4) Finch is as much hero/protagonist as Evey—and his solution is not to replace V, but to walk away from the whole mess. 5) Nobody talks about this, but I’m semi-convinced that the book is explicitly linked to Conrad’s Secret Agent, where anarchy is repeated referred to as equivalent to its obverse–anarchist bombers with “V” names is the connection that seems too obvious to be coincidence (although, admittedly, it could be). Just taught the book, so I’m even more convinced that the ambivalence of V’s heroism is both emphasized and, in some ways, obvious.

Using the superhero genre problematizes things, since the genre is, by its nature, “fascist” in certain ways– and celebrates power/dominance, etc. V is not Moore’s most effective interrogation of heroism and “ubermenschery”–but it is part of his general commitment to doing so, at least in the work of the ’80s.

As usual, Bert makes little sense to me…But, I would say, at least partially, “the rapture of the author” is about playing God and exerting control. Admittedly, there’s no “real” violence in the author’s role, but there’s still something “fascist” about it–an intoxication in power and control that is not so different from that of the dictator. In many ways, V is an author figure, for instance–controlling and setting up all events, etc.

Yeah…still not convinced. For example, the links with Susan are all in V’s favor. V undermines his power and steals his thunder, but V is not implicated in his sexual perversion (for example.) And it’s Evey who’s the emotional heart of the book, and she becomes V.

As I think I said before, you’d be on much firmer ground if anyone in the book ever explicitly made the case against V; if Evey, for example, managed to articulate a convincing “you’re another” critique. But she doesn’t, and nobody does, and he gets a viking funeral and deliberately lays down his power, demonstrating that it *isn’t* about power for him and he isn’t a fascist.

There’s some effort at balance…but the genre tropes ultimately defeat Moore, I think, and he ends up canonizing V. Miracleman is much more successful in undermining its heroes…and Watchmen is more successful than that.

When V orders everyone to be free in the TV Studio, the irony drips. “You have one year to do what I say–and be free!”

But yes—the fact that V gets to remove himself, abdicate his fascist throne, and all that, does place him back in the hero role. I don’t think the genre tropes defeat Moore so much as Moore really does advocate anarchy over fascism—so tries to make that “side” win, despite his simultaneous (and somewhat contradictory) effort to make it clear that V’s methods are problematic–and even linked to fascism.

So–there’s a bit of backtracking at the end. I’d agree with that. But there is definitely ambivalence toward V built in to the majority of the narrative.

Watchmen’s ending is much more “up for grabs” obviously…and endings can’t be disregarded.

“V undermines his power and steals his thunder”. Ok…but since “power” and hierarchy are exactly what is under critique, when V steals it, he taints himself.

I also am not so sure that V is completely desexualized. He’s a daddy figure for Evey—as is Gordie, whom she ends up sleeping with. Indirectly, it’s fairly clear that Evey “gets off” on the hierarchical power relationship with V (in masochist fashion)—She even offers herself to V. Just because he doesn’t jump at the chance doesn’t mean it doesn’t appeal.

In fact, V’s “chastity” links him to Susan as much as it separates them.

Anyway, you’re wrong—but I know you’ll never admit it!

I think it’s a mistake to view V through the superhero template.

As Moore himself points out, that’s an American, not a British, archetype; the corresponding British archetype is the uncatchable villain: Dick Turpin, Varney the Vampire,Sweeny Todd, Raffles, Spring-Heel’d Jack, the Spider, the Claw…even Robin Hood, when you stop to think.

V was very deliberately modelled on this British villainous template.

It’s in a comicbook; he’s got superpowers; he’s got a superhero origin. Whatever Moore may want him to be, he’s a superhero.

You could say the same for Adrian Veidt. He is a superhero. But he’s also a supervillain. Why is that V can’t be both as well?

He could be; it just happens to be he isn’t. Moore makes it clear that Veidt is fallible; includes explicit critiques of him in the story; and generally challenges his perspective. That doesn’t happen with V.

Doesn’t it? What would V’s new world be like? In the book there’s a subplot involving gangsters that implies that along with anarchy murderous chaos looms.

And the British supervillain tradition also involved super-powers and comics.

Remember, V started as a serial in a British b&w newstand comic, so its intended readership was very familiar with the villain-strip tropes.

I don’t know that Morrison has gotten better or worse over time. It’s always been a very mixed bag. “Doom Patrol” did have its share of worthwhile cleverness, but overall storywise it was a train wreck especially as time went on. “Animal Man” also had its moments, but I don’t know if its even worth wading past such terrible stories (like the “dolphin” one) to get to the best parts. His current run on “Batman”…… Let’s put it this way: the opening storyline from some years back ended with that hoariest of cliches- the adversary causes an explosion leaving no trace of her whereabouts. I guess that’s what he’s willing to settle for….

I don’t think he’s cynically pandering… I don’t think he ever is really taking the piss out of super-heroes exactly. Affectionately ribbing them maybe. Parodies are kind of part of the super-hero thing, and Morrison probably gets that.

Perhaps, but do the artists he work with get that? The Superman page above does nothing but pile on the portentousness and fascism that comes naturally from that character…

I love Animal Man. Though the dolphin story probably does not hold up. The Coyote Gospel is still probably the best thing he’s done though.

I don’t think Morrison is trying to do a parody in that panel….