I wanted to comment on Matt Seneca’s blog about this picture , but the site or my browser is wonky so I couldn’t, so what the hell. We’re not at tcj any more; I can do short posts twelve times a day if I want. Who’s to stop me?

Anyway, Matt argues that Eisner’s use of Ebony White is comparable to Mark Twain’s use of “nigger” in Huckleberry Finn.

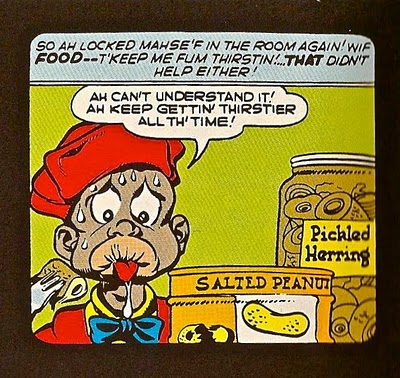

When I try to think of a comparison for the comics field’s benign neglect of Eisner’s Spirit work, the first thing that jumps to mind is the recent, much-maligned “New South” edition of Huckleberry Finn, which replaces all Mark Twain’s original-text uses of the word “nigger” with “slave”. New books for a new world. But it’s not a perfect comparison because Ebony White, the ridiculously offensive racial caricature above, was the Spirit’s sidekick for the better part of a decade — and this being comics, there’s no easy way to replace Eisner’s cringe-inducing pickaninny with a more palatable depiction of the black kid who helped Denny Colt’s alter ego out of many a jam when he wasn’t commenting wryly on the hero’s tangled love life. Instead, The Spirit remains shielded by comics, never really put forward as a sterling exemplar of the form by its critical community or marketed with the aggression the material deserves by DC, who own the trademark. There’s a very real fear that comes into play when the medium’s spokesmen, whether aesthetic or commercial, deal with Eisner’s masterpiece — a nervousness that the wider world simply won’t be able to take the skeletons in comics’ closet.

Matt goes on to compare Ebony to Huck Finn, and argues that the character is vital and funny enough that you can almost forget the racism.

I’m pretty sure I immediately think of the New South Twain book when I think about Ebony because he just might be the closest thing to Huck Finn that 20th century pop culture produced, a gutsy, vulnerable, melodramatic, flawed, truly good kid trying to find his way in a world that’s thrown him into an array of increasingly outre characters. He’s the most fun part of pretty much every Spirit story he appears in, the “kid sidekick” archetype done better than anywhere else; driving the action forward with youthful impulsiveness here, saving the day with a child’s wisdom there, and providing a steady stream of arch, borderline satirical meta-commentary whenever else. It’s also interesting to see the way that Eisner’s playing to reprehensible stereotypes works as effective character construction in a world that no longer traffics nearly as heavily in overt racism. Ebony’s grossly patois-laced dialogue, his minstrel-show pratfalls and caricatured appearance and body language serve to give him more sheer personality than any of the numerous ciphers that filled up the rest of Eisner’s stories. Ebony was a springboard for some of Eisner’s funniest humor material — humor material, let me add, that never succumbed to racial jokes, which supports the view that Eisner was simply blinkered by his times and harbored no particularly intense prejudicial malice — and the subject of his most affecting and least cloying paeans to the freedom of boyhood. He’s always the thing on the page that’s most alive, most unpredictable (by comparison the Spirit is little more than a one dimensional wind-up fighting machine) — and it’s a testament to Eisner’s strength as a storyteller that you can almost forget all that energy is generated by pure racism during the best sequences.

I’m not super familiar with the old Spirit stories. When I’ve read them they tend to bore me; fairly tame genre stuff, it seemed like. But I’m willing to accept for arguments sake that they’re better than I thought, and that Ebony White is a great, funny character despite being a disgraceful racial caricature. I’m willing, too, to accept Matt’s argument when he says that Eisner’s was a “casual racism”, more about prevailing cultural mores (which were very racist indeed at the time of the writing of the Spirit) than about strong personal animosity.

The problem here is…well, none of this actually makes Eisner look anything like Twain. Twain wasn’t a casual racist. He was an ideologically committed, angry, courageous anti-racist. The whole point about the “nigger” controversy in Huck Finn, the reason it’s so wrong-headed is that the book is about the fact that slavery is evil and black people deserve to be treated as human beings. Twain’s later masterpiece, the searing “Puddin’head Wilson,” is even more explicit and devastating. A black light-enough-to-pass slave switches her own son with the lord of the manor’s child; the black child grows up to be a swaggering, evil bastard, and the cause is pinned firmly not on the fact that he’s (nominally) black, but on the fact that owning slaves is evil and corrupts everyone it touches.

This isn’t to say that Twain had no touch of racism; the slapstick end of Huck Finn comes close at points to forgetting that Jim is human, turning him into a carnival butt and almost ridiculing his desire for freedom. But the point is, Twain actively struggled with the evils of racism, and mostly came out on the side of the angels.

This is very different from Will Eisner. And it’s part of the reason why this is just wrong:

Eisner has an alright case as comics’ Twain, to be honest, a massively influential yarn-spinner whose tendency toward painting in broad strokes may get in the way of his status as a true master of his medium, but whose ability to entertain keeps him deeply relevant while veiling a massive amount of nuance.

Twain isn’t just a influential yarn-spinner; he didn’t paint in broad strokes — at least not always — and there is nothing and no one who stands in the way of his status as a true master. Twain wasn’t an entertainer in Huck Finn and Puddin’Head Wilson — he was one of the most honest, most perceptive, and fiercest critics of America’s original sin. That’s (one of the many reasons) why he’s considered a great writer; because of his treatment of race, not despite it.

And that’s why this summing up is deceptive as well:

But as an expurgated Huck Finn is, so is a whitewashed comics history that shies away from confronting the sins of the past, especially when it happens at the expense of great work. Strangely, perversely, Ebony White is one of the most interesting parts of Eisner’s Spirit, a look into that textured, carnivalesque America of yesteryear that reminds us it wasn’t all unambiguous heroics.

Cutting out “nigger” from Huck Twain defaces one of the great anti-racist texts we’ve got; doing so lies about the nature and the contours of the struggle against. On the other hand, Ebony White doesn’t show Eisner struggling with racism. It just shows him being racist. And when you talk about Ebony White as part of a “textured, carnivalesque America of yesteryear,” you come really close to celebrating it for its racist caricature. Because that textured, carnivalesque America? It was really racist — more racist than Mark Twain’s America, in many ways, which still had a strong strain of racial idealism and hope which got crushed after massive Southern resistance to Reconstruction.

The point is, The Spirit is significantly more racist than Huck Finn, as America in Eisner’s time was more racist than America in Twain’s. For his time, too, Twain was anti-racist, while Eisner was, for his, just casually, everyday racist. I don’t think that means that Ebony White should be censored, and I don’t think it means that no one should enjoy reading the Spirit. But I also think that if someone were to look at The Spirit and say, “fuck this racist shit” — well, that would be a really, really defensible position, because that shit is racist. America still needs anti-racism; it still needs Huck Finn and Mark Twain. Ebony White though? Even if he’s all that Matt says he is, I think the culture is probably paying the Spirit’s sidekick just about as much attention as he deserves.

Update: If wading through the comments is too much, I’d encourage you to at least read what Jeet Heer has to say about Ebony White.

…yeah there we go, I was waiting for this response. Glad it was as eloquent as your article, Noah. That’s why I said the analogy isn’t perfect, and that I just THINK OF Twain when I THINK OF Ebony White. For all Twain’s anti-racism (and I’m not denying that aspect of his work by not discussing it in my article), he did write some pretty racist caricatures in his day too — Jim may be human in Huck Finn, but he’s at least as bad as anything Eisner did in Tom Sawyer Abroad, for example. Similarly, Ebony’s a more human character than pretty much any other of the racist stereotypes he shared a face with. I was trying to talk about how there can be redeeming value under the obvious surface of racism. Yeah, “fuck this shit” is a perfectly valid response to the Spirit, and I’m not saying people shouldn’t be allowed to have it. But… I dunno, “fuck this shit” is a response a lot of people have had to reading Huck Finn too, and just as there’s something beneath Twain’s use of a racial slur, I think there’s more to Eisner’s Ebony than simple racial malice. Not sayin’ that something is the same thing in both cases, just that they’ve got something in common.

Thanks for writing about me!

Matt and Noah:

Have either of you looked at Chinua Achebe’s critique of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness? Conrad’s diminished standing in literary criticism post-1975 (when Achebe gave his speech on it at U Mass Amherst) might be useful for comparison with the Eisner situation because it gets at the specific issue that Matt raises about The Spirit — that it deserves critical engagement despite the racial issue, but that it doesn’t really get it. I am failing to quickly find a copy of the talk (although I’m sure it’s online) but wikipiedia did yield up this quote from Achebe when asked about it:

It should be possible for The Spirit to have the same ambivalent critical standing, where sophisticated readings that emphasize its achievement stand next to the reading that calls it out on its racism — but I’ll offer up for the sake of argument that Achebe’s critique really did damage the standing of Heart of Darkness among the literati, and that you’re kind of in a critical pickle when the critique of racism precedes the criticism pointing out what’s good about the work.

It’s already pretty much not done to say positive things about even a relatively well-respected work without pointing out any racism, so to try and rehabilitate an underappreciated work that has racist overtones or elements is almost impossible. There are comparable situations to the Eisner with Disney’s Song of the South, or minstrelsy…the rights owners of that material are hesitant to promote it too…

Hey Matt! It was fun to think about Twain again! I haven’t read Tom Sawyer Abroad…but surely it’s lack of cachet has something to do with its racism as well?

I think I get where you’re coming from…I don’t think it really works quite the way you want it to though. I wonder if the one-panel critique is really the best way to get at this issue? Racism is really complicated, and I’d be interested to see how precisely over his work Eisner deals with it. You’re trying to get the Twain analogy to do too much work for you, especially since Twain really did confront racism in a way that I don’t think Eisner does. You end up saying something like, “we shouldn’t forget racism, in part because it’s colorful and textured,” which isn’t where you want to be, I don’t think — at least not without a lot of ambivalence.

I think the comparison with Herge works a lot better, though you don’t follow up on it exactly. And a discussion along the lines of what Alex did with Herge, talking about how Eisner responded to charges of racism and tried to adjust over time, could be interesting. But you don’t really make the case that there’s something beneath Ebony other than racial malice, I don’t think. I mean, you make the case that Ebony is a funny character, and you make the case that Eisner’s racism was pretty casual, but neither of those add up to an engagement with the issue of race like Twain’s or (over time) like Herge’s.

I mean, you could say what I’ve said about McCay — which is basically that the racism is casual and tangential and there are formalist elements you can enjoy instead; that is, really an argument that there’s worth despite the racism. But you seem to want to have the handling of race itself be worthwhile and interesting — and as I said, I don’t think you really close the deal.

But it was interesting to think about, in any case. And thank you for stopping by the new site! It’s nice to know we’re findable!

Here’s the essay although I’d copy it into a Word document because it’s formatted awfully. The beginning is compelling, as one would expect from Achebe:

Read the essay if you haven’t. It’s quite marvelous, and its impact is easy to understand. But then think about how extraordinary an literary achievement Heart of Darkness is, and if even a work of that standing was susceptible to the power of this argument, AFTER the arguments for its significance had been made and accepted, I think it’s easy to see why The Spirit is underappreciated…

There’s also a recent interview with Achebe on this here: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=113835207

Noah,

longer post coming at some point. but it takes a long time to read back through all those spirit archives

I’m pretty sure I’ve read the Achebe…or read so much about it I think I have, anyway.

Heart of Darkness is still pretty solid. It’s also much, much more sophisticated in its handling of issues of race than the Spirit is, at least from what I’ve seen or read about the Spirit. Heart of Darkness is about race, and about the evils of colonialism and racism. I think Achebe’s got him dead to rights in saying that the racism is still there and still important…but there’s just an ambivalence and an engagement that isn’t there in Eisner, I don’t think. (I mean, you could argue me out of that position in theory, but Matt doesn’t do it here.)

Oh, cool Matt. I’ll look forward to the longer post!

Pretty solid — but still susceptible to the critique…

I’m not sure the relative sophistication of the racism in a book makes a lot of difference in how this plays out. There’s a certain extent to which racist imagery is a mark that just makes people step away from the work. Achebe says in the NPR interview that if people “want to go on enjoying the presentation of some people in this way — they are welcome to go ahead.” Nobody wants to be the person who “enjoys the presentation of some people in this way.”

So you might get an academic appreciation of The Spirit by people who are comfortable finessing the notion that appreciation isn’t the same thing as enjoyment, but I think it’s gonna be a high hill to climb for anything else.

Twain doesn’t trigger that situation, because you’re so clearly not supposed to enjoy the racist representation…

Well…and also because there’s a decent case to be made that the representation isn’t racist in Twain (I really don’t think it is in something like Puddin’Head Wilson.)

I guess there’s a question for me of whether it’s really wrong or a problem that the Spirit isn’t more appreciated. Eisner’s quite appreciated…and I find his work fairly tedious for the most part, even absent the race problems. Lovely drawing and design often; I can enjoy that. But overall; eh. So given that and given the racism…it’s just not clear to me that this material should be more appreciated than it is, you know?

I’m waiting for Domingos….

Some of the lack of real critical engagement with The Spirit could be the lack of affordable editions. Those DC Archives are expensive.

Yeah, in Twain it’s a “representation of racism” more than a “racist representation.”

Derik, I think Matt is arguing that there aren’t cheaper editions because no one but collectors wants the stuff because the racism makes it unmarketable. Which seems believable.

I really don’t who Achebe thinks “enjoys” the imagery of slow-motion genocide that Conrad depicts. I guess he feels those who find that imagery horrifying are masochists getting off on our “bleeding-heart sentiments.”

Of course Conrad depicts the Congo as “the other world.” The story is told from the perspective of a European! A story about a Nigerian who suddenly found himself transplanted to, say, London, would depict England as “the other world,” too. And his discomfort would likely be expressed in negative attitudes towards his new surroundings as well. The story would probably ring false if this weren’t the case.

What Achebe is essentially complaining about is that Heart of Darkness is about one thing and not another. Its subject is the evil colonialist exploitation engenders, and it reserves its greatest “horror” for the moral vacuum that this evil arises from. Conrad takes considerable care to render the atrocities colonialism inflicts. What Achebe doesn’t like is that it’s not Conrad’s primary subject. But that attitude should be an impetus for his own work, not an effort to delegitimize Conrad’s.

To the best of my recollection, Conrad does not invite one to hate or sneer at Africans. His attitude is at worst patronizing, and all that does is mark him as a product of his times. I’m sure Chinua Achebe has done things that might be viewed with disdain by the standards of the 22nd century–for example, I’m sure he’s made use of such pollution-creating transportation as automobiles or airplanes. However, it’s ultimately fatuous to criticize him for it. Thomas Jefferson is a great man regardless of whether he owned slaves.

Robert — none of it changes the fact, though, that the essay really did a number on Conrad’s standing, or that people rarely talk about HoD anymore without mentioning the ways in which the representation of Africa is problematic…

And it was an impetus for his own work! Things Fall Apart is a response to Heart of Darkness; he did write the “other thing” that you’re suggesting he write.

The essay isn’t in the least bit fair to Conrad, though; you’re right. But it’s thesis is overtly that Conrad doesn’t deserve to be treated fairly, that the “patronizing” attitude is a more insidious kind of racism than the overt kind. It’s certainly an arguable point, but it’s influence is pretty hard to dispute…

Has it brought him down all that much? He’s still so widely taught, and it’s usually that book that gets assigned. I can only speak anecdotally, but I think everyone I knew at NYU English had read it for class at some point.

Noah: Oh, I missed that. Didn’t realize Ebony was that prevalent in The Spirit. I have one greatest hits type book that DC put out. I think he is completely absent from it… which I guess speaks to the point. There are a few stories with the annoying big-faced white kid they replaced Ebony with later in the run.

Derik, I may be wrong, but I think the greatest hits volume you are mentioning recolored Ebony in whiteface. At least a colleague who used a relatively affordable trade told me this was so… perhaps extending in unfortunate ways the analogy to Twain given recent news.

Noah, re:

I always have assumed that the treatment of Jim at the novel’s end was to demonstrate how things go so horribly wrong once Tom arrives and imposes his Walter Scott fantasies on events, and Huck’s weakness for allowing himself to be so dominated– not, that is, as an invitation to anything like enjoyment in the way Jim is treated.

Noah: “I’m waiting for Domingos…”

I don’t have much to say, really. _The Spirit_ is quite mediocre and its canonical status is just prof of the indigence of comics criticism.

“But then think about how extraordinary an literary achievement Heart of Darkness is, and if even a work of that standing was susceptible to the power of this argument, AFTER the arguments for its significance had been made and accepted, I think it’s easy to see why The Spirit is underappreciated…”

Caro, I think the mistaken impression here (and in Matt’s piece) is that Eisner’s Spirit is under appreciated. Almost all of Eisner’s later work (that hopeless flailing about that has been labelled “adult”/”mature”) has fallen by the way side and it is The Spirit which holds a central place in his oeuvre in this day and age. Groth dismantled Eisner’s post Contract of God work in the 80s and The Comics Journal’s position as evidenced by their TCJ 100 list (concocted by a group of critics with a more traditional bias) is that The Spirit is far superior to anything he did. This has become the dominant position outside of fannish circles. Hence Domingos’ statement above. Very few critics are exercised by Ebony White who remains pretty impotent as a racist caricature, the product of a very ordinary mind when it came to cultural issues. People are way more interested in Eisner’s formal abilities.

>>People are way more interested in Eisner’s formal abilities.>>

Interesting how a few of these formal abilities were in actuality the abilities of his associates. I consider the expressive lettering the real visual contribution of the Spirit to comics culture, and I was shocked to find out only a few years ago that it was the work of one of his many assistants. I’ll touch on this briefly in a post tomorrow.

Yeah, I would second Suat: The Spirit is definitely not underappreciated. It’s one of the canonical American comics and the main reason why the most prestigious industry awards are named after its creator.

But for all that, the comic is remarkably understudied. In terms of its racism, which is undeniable (although I agree with Matt that the ubiquitous Ebony is its most interesting, even vibrant, recurring character), and has never really been examined in depth.

But also in terms of its creation: *how exactly was that strip created and what was the contribution of Eisner’s collaborators? As with Hergé, it’s clearly Eisner’s work — his auteurial presence is undeniable — but at the same time many of its great stories and formal inventions seem to have been thought up and executed by others. Eisner has been so good at propagating his own myth that these issues have rarely been addressed more than superficially.

And for my part, I actually miss an effort to articulate just why the strip is deserving of its status: its alleged greatness is generally taken for granted amongst the fans, while most of its, and Eisner’s, critics have basically taken Domingos’ position. I believe there is clearly another way of looking at it and justifying its value as a work of art beyond those rather trenchant receptions.

Matthias: “Eisner’s, critics have basically taken Domingos’ position.”

Who are they? I’ve never met one…

By the way: I meant “proof,” not “prof,” and I meant “evaluative criticism.” I have a lot of respect for comics scholarship in academia.

How ’bout “I think it’s easy to see why The Spirit could be underappreciated…”

I was just taking Matt’s word for it…

It’s not Achebe, but I find her interesting: http://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story.html

Hasn’t Gary gone after Eisner in the past? DId I hallucinate that?

No, you didn’t, but he didn’t touch _The Spirit_ which is untouchable.

Yup, what Domingos said.

The screed was mainly against his “graphic novels”. Eisner’s Spirit pops up at #15 on the TCJ 100 list which was voted on by Gary, Kim, Robert Boyd, Charles Hatfield, RC Harvey and Ray Mescallado. Gary put Eisner at #23 on his personal list.

So *nobody* thinks the Spirit is kind of dull?

Maybe I looked at the wrong ones or something, but I found it pretty unreadable. Nice art though.

The Spirit sections don’t read well in large chunks, and the Archive collections qualify as large chunks. I have every single one of them. Don’t test your patience with them or listen to people who tell you that the Outer Space Spirit (for example) is some sort of “masterpiece”. Get the primers and “best of” collections (the old Kitchen Sink ones are fine). Might be better to see The Spirit as a high jinx adventure serial with a conglomeration of formal tricks; you have to be attuned to the times and the nostalgia I suppose.

You have all of them! Good lord. I think I’d rather undergo some sort of minor surgery than read the entire collected Spirit….

Nah, you don’t have to read all of them. You can use them as reference books or just flip them for the art if you feel lazy. There are “famous” periods of The Spirit like when Eisner was doing most of the drawing duties or when major characters are introduced or recur. But you are correct in implying that the Spirit Archives is a bad place to start for newbies. Having said this, I wouldn’t want to read 10+ years of Peanuts without break either. Those digest size editions are just right (particularly for kids I think).

Oh! Being as I am quite DEEPLY attuned to the time, I think I really REALLY need to read Outer Space Spirit. I mean, ’52, an experimental moon mission, written after Eisner had been working on instructional and commercial material for the military…that sounds like the absolute ultimate ’50s space kitsch.

(And do, please, imagine my saying “absolute ultimate” in my absolute best Judy Jetson voice.)

Speaking of mid-century space not-kitsch, it’s the 50th anniversary of Gagarin’s flight and there’s a comic to commemorate it:

http://www.themoscowtimes.com/arts_n_ideas/article/gagarin-blasts-off-comic-book-style/431022.html#no

Oh dear, that does not look like a very well drawn comic. I was at Star City last year and did the usual tourist things (visited the centrifuge, underwater-weightlessness training centre, Gargarin museum etc). Quite run down as you would expect but that only made it seem more real (not Disney-fied yet). People still seem to live and work there, and the Russians seem quite proud of their achievements (as they should be) – lots of history.

I won’t talk about the Outer Space Spirit since you’re going to read it…and write about it (??)

Pingback: Comics Time: “Flash Roughs/In a Hole: Jul-Aug 2010″ « Attentiondeficitdisorderly by Sean T. Collins

Was Eisner involved with The Outer Space Spirit? I thought that was Jules Feiffer and Wallace Wood working on their own. I think Feiffer’s on the record as having hated working on it. What I’ve seen of Wood’s art in it is really gorgeous, though.

—————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

I’m not super familiar with the old Spirit stories. When I’ve read them they tend to bore me; fairly tame genre stuff, it seemed like.

—————–

Oy! It’s as if – as was the case with some old Hitchcock you dissed – you only notice the nothing-special genre plot, and not the delicious artistry and wit with which it’s executed; brought to the screen/comics page.

—————–

Domingos Isabelinho says:

I don’t have much to say, really. _The Spirit_ is quite mediocre and its canonical status is just prof of the indigence of comics criticism.

—————–

Same case here, from the “Jack Kirby’s comics don’t feature ‘serious,’ adult themes, therefore Kirby can be dismissed as artistically worthless” chap…

—————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

I’m willing, too, to accept Matt’s argument when he says that Eisner’s was a “casual racism”, more about prevailing cultural mores (which were very racist indeed at the time of the writing of the Spirit) than about strong personal animosity.

—————–

I’d argue, instead of there being any racism involved, that Eisner was simply following the cartooning tropes of the time, which dictated that blacks should be depicted in that fashion. (Any examples of “period” cartoons which did not follow that custom?)

Why, hideously, there was a time when blacks onstage were required to put on blackface…

—————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

The problem here is…well, none of this actually makes Eisner look anything like Twain. Twain wasn’t a casual racist. He was an ideologically committed, angry, courageous anti-racist.

——————

Indeed, he’d be called a far-leftist these days. Was a member of the Anti-Imperialist League, which opposed the U.S. taking over the Philippines, for instance…

And yes, Twain wasn’t calling Jim “nigger Jim” with unthinking usage of the popular term of the time; he was deliberately contrasting the ugly word with a nuanced portrayal of a richly human character.

But, now that I think of it; isn’t Eisner’s usage of the period’s visual jargon for depicting blacks, when contrasted with the often resourceful and heroic qualities which Ebony showed on many an occasion (“He was even a skilled pilot and flew the Autoplane on various missions for the Spirit,” reports http://www.comicvine.com/ebony-white/29-27735/ ), have a similar effect? In other words, one character may look clownish, another be referred to as “nigger,” yet both are – subversively – depicted as fully-rounded human beings.

Not that I think Eisner was necessarily consciously plotting to fight racist attitudes, the way Twain surely was. But let’s not forget that Jews used to be on the forefront of liberalism, and in supporting the struggle for civil rights, so Eisner was likely to be – if hardly a committed anti-racist like Twain – no unthinking supporter of racism.

Milton Caniff’s buck-toothed Connie seems a similar stereotypically-rendered, yet overall positive character, as well.

——————-

Ng Suat Tong says:

The Spirit sections don’t read well in large chunks, and the Archive collections qualify as large chunks. I have every single one of them. Don’t test your patience with them or listen to people who tell you that the Outer Space Spirit (for example) is some sort of “masterpiece”…

——————–

Good grief! The Outer Space Spirit – written by Jules Feiffer, as I recall, much art by Wally Wood – is awful; gloomy and morose; utterly lacking in the delight in the art form and exuberant inventiveness of the classic strips.

Dunno how affordable or “findable” they are, but Warren published a series of magazine-sized, b&w reprintings (with new color covers by Eisner) of the Spirit stories, too. Lemme Google an’ see: http://www.mycomicshop.com/search?minyr=1974&maxyr=1974&TID=183251 , http://www.wildwoodcemetery.com/publishers.shtml .

Speakin’ of Google’ing, check out “Addressing Ebony White — Was Will Eisner Racist?” – http://www.comicscube.com/2010/05/addressing-ebony-white-was-will-eisner_26.html – featuring a brain-blasting scene of Billy Batson disguising himself with burnt cork…

Duy, the site’s author, mentions:

———————-

And actually, in later strips, Eisner actually introduced a black detective who was neither in blackface nor was he in there for comic relief. (I can’t, however, for the life of me, remember his name, or find an image of him, so if anyone can refresh my memory, I’d appreciate it.) That was more progressive than just about anything else they were doing then, so even if Eisner is responsible for the creation of, to hardcore liberals, one of the most racist characters ever, he was also one of the first to actually portray blacks as competent and intelligent. That last part, of course, isn’t as publicized or as well-known, because, of course, it’s controversy that actually goes around and talked about, and I think that those who boycott The Spirit because of Ebony White are really doing themselves a disservice. Things were different back then. I wonder if they would boycott Peter Pan too for its portrayal of Native Americans?

————————–

Domingos, I haven’t seen a lot of people take down The Spirit in print — as I said, I haven’t seen much quality criticism of the strip at all — but I’ve spoken to quite a few comics people who aren’t all that impressed and more or less could be described as being in line with you.

I don’t know if it’s “untouchable” so much that no-ones really bothered to write negatively about it. There’s still so relatively little comics criticism around that many such “holes” appear. Another canonized strip which could benefit from a critical reassessment in this way is Harvey Kurtzman et. als. Mad.

You should do both Matthias! I would love to print such things….

Maybe we could convince Domingos to do a rebuttal….

Suat did critique Mad in TCJ.

During the 1970s, I read most of “The Spirit” strips that were reprinted up to that point, and, while I’m going strictly by memory here, it was not the primarily the writing that made Eisner’s work so ground-breaking, it was the way he combined words and pictures to TELL a given story.

In short, in most cases, the basic story itself, and even the characters themselves, DIDN’T MATTER.

Eisner’s story-telling genius was primarily in his unique visuals and ability to manipulate story flow and timing, NOT so much in his basic literary chops.

That said, as I recall, about a half-dozen or so of the strips I read in the 1970s could arguably be referred to as literary masterpieces.

Eisner, like any artist (or artistic discipline, for that matter), should only be judged by the best examples of his work. Consider the rest to be nothing more than the chaff that was necessary to create the wheat.

There’s no justifying Ebony, or the actions of any of Eisner’s characters — all of whom were stereotypes of their era (I mean, c’mon — look at Commissioner Dolan!). Writers and artists then, as now, often relied on contemporary stereotypes to appeal to, and strike a chord of familiarity with, their target audience.

By the same token, art, literature and popular culture today are rife with stereotypes — stereotypes that will no doubt be glaringly evident to audiences 100 years hence. So I think it’s unrealistic to single out and fault Eisner for his use of stereotypes 60-70 years ago.

I don’t know, Russ. Ebony is a really invidious, racist stereotype. It’s explicable as part of the mental furniture of the age…but that mental furniture was really racist, and it’s not excusable. It mars the work for many, including myself. That doesn’t mean there’s nothing else about the work that’s worthwhile, or that it can’t be enjoyed…but I don’t see making excuses for it as very useful.

“Derik, I may be wrong, but I think the greatest hits volume you are mentioning recolored Ebony in whiteface.”

Jared: I don’t think so, not the one I have at least (from DC). I don’t see any indication of Ebony, and at the end there are a few stories with Sammy the little white kid. He’s definitely not a white-faced Ebony… well, he kind of is, in that he was (as I understand it) the white kid who replaced Ebony, but it’s not a reprint editorial thing. (The total removal of Ebony from the book sure seems like it is.)

Personally, I find the Spirit pretty blah. Sure, there are formalist reason to read (or better just look) at the art/layouts/etc, but the stories themselves alway seem like pretty trite genre exercises.

Noah: If you haven’t read Groth’s takedown of the later Eisner works, I can send you a pdf of it.

Oh yeah, Suat’s piece on EC was excellent. I’d forgotten that it also addressed Mad. Maybe it could be reprinted here?

I’d love to write something on Eisner — I’ve long wanted to — but I don’t have the time to commit right now. Perhaps later in the year.

RSM: “Was Eisner involved with The Outer Space Spirit? I thought that was Jules Feiffer and Wallace Wood working on their own. I think Feiffer’s on the record as having hated working on it.”

Yes, the version I’ve heard is that Eisner suggested the idea, Feiffer hated it but eventually decided to do it. When Kitchen Sink released their collected Outer Space Spirit, they included Feiffer’s name on the inside title page but not on the cover. Just about says it all, doesn’t it? According to Eisner he talked a lot with Feiffer about his ideas for the storyline before Feiffer broke it down into layouts/script, hence the double credit. He concludes:

“…but it didn’t work…in the end I was back inking the figures as well as penciling, and Wally was doing backgrounds, which he did not want to do. It was a short marriage.”

Matthias, later in the year would be great. No rush!

Also, I’ve tried repeatedly to get Suat to reprint some of his old Journal pieces. No luck as of yet, but…Suat, what say you?

Probably not. Even the acceptable ones need a bit of rewriting/reworking before being acceptable.

That’s a pity. I was mulling a post on superheroes before comics– starting from Monte-Cristo on up, an idea suggested by Umberto Eco– and your article on superheroes after comics would have made a good bookend.

See! See! This is the sort of thing he always says.

I need to lock you and Bill Randall in a room, Suat; you can force him to publish his old writing and he can force you to publish yours.

This whole having standards thing; it’s death, I tell you, death. We’re on the internets! People tweet about the state of their bowels in barely coherent sentences! Embrace your inner Kerouac, damn it!

Noah wrote: “It’s explicable as part of the mental furniture of the age…but that mental furniture was really racist, and it’s not excusable.”

I think it is. Do you think Eisner died a “racist”? I sure don’t.

I’ve said this before and I’ll say it again, during that era, I’d argue that EVERYONE was a racist by today’s standards — and, as odd as it may sound, they were racists regardless of their race.

For example, revisionists today look back at period American charicatures of the Japanese with horror, forgetting that the Japanese viewed us with equal racism, along with practically every other culture in the world. The Japanese did not set out to conquer Asia simply to grab raw materials, they did so because they thought all the cultures around them were inferior and did not deserve them.

Come on, even Eisner found Ebony embarassing as the 40s rolled on.

I didn’t mean that Eisner died a sinner and should never be forgiven. I meant that the racist caricatures in his work should not be excused or brushed aside in an evaluation of his work (that is, of the work in which they appear, not of all his work forever.)

The Japanese had (and still have, to some extent, like us) serious problems with ethnocentrism and imperialism. I don’t think anyone denies that. I don’t see why that excuses our treatment of Japanese-Americans during the war, though (to cite the most egregious example.) Two wrongs, etc.

Claiming that it was just the way it was at the time is really unhelpful, I think. First of all, it’s important to recognize that it was worse when Eisner was writing than it is now — and especially that it was worse than it had been in the past. America made a decision to abandon racial idealism. Eisner’s work was part of that decision; a small part, but still reprehensible as such (which isn’t to say it can’t have other good qualities.)

Also, it’s simply not true to say that everyone at the time was equally culpable or equally to blame. There were people and artists around that time, even in the pulp field, who were committed to working against the racial stereotypes of the time. Moon Mullican, for example, recorded in interracial settings. Slightly later, Wanda Jackson had an integrated band, for which she took a certain amount of shit. Or there’s Artie Shaw. And that’s just white people; obviously folks like Langston Hughes (who wrote in popular venues) and Billie Holiday were much more aware of these issues (it’s kind of insulting to them to even put it like that, really.)

And as Alex I think indicates, it’s kind of disrespectful to the later Eisner to argue that there was no problem with Ebony White. Eisner repudiated the figure, rightly and I think honorably. Insisting that there was nothing to repudiate in the first place robs his later change of heart of meaning, which I think diminishes him.

Tangentially related, but as we’re on the topic of racially charged imagery — The Russian animator Ivanov-Vano did an interesting propaganda piece on race in the US in 1933:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3YHE1w0v5H8&playnext=1&list=PL9AD8230EF189190E

Just to expand a little…pointing as a comparison to music is interesting I think. There has been a (vacillating, imperfect, but still) strain of integrationist idealism in popular music for more than a century, from jazz to early rock to today’s r&b and hip hop. That’s adamently not the case in comics, which has had historically few black creators and (probably not coincidentally) a lot of racist depictions. I think it’s important to think about Ebony White in that context, rather than just saying, “well everyone was racist back then.”

I’m on deadline so can’t respond at length right now but basically Noah is closer to the mark on this than Matt is. Eisner was no Mark Twain; in creating Jim Twain was able to do something miraculous: take a minstrel stereotype and imbue him with human feelings (most of the time: Huckleberry Finn is a very uneven work). Ebony White was closer to Amos and Andy than to Jim: i.e., not a malicous or hate-filled stereotype but just a condescending one.

One other point: it really doesn’t work to say that Eisner was a product of his time: the civil rights movement was already challenging stereotypes in that era and many cartoonists responded by trying to create more believable black characters. By the late 1930s in Gasoline Alley Rachel stopped being and maid and set up her own household; in Little Orphan Annie circa 1942 Harold Gray created a very smart, non-stereotypical black boy named George who befriended Annie; and in his Our Gang stories Walt Kelly took Buckwheat (who started off not dissimilar to Ebony White) and made him an equal to the other white kids. So Eisner didn’t represent the way everyone was in the 1940s; in many ways he was behind the times. And he got rid of Ebony because black readers complained and also his very young assistant Jule Feiffer didn’t like Ebony. Again, a sign that Eisner wasn’t leading the pack but rather responding to other people who were more progressive than he was.

I’ll add that in addition to Ebony White, Eisner also created Chop-Chop (the very stereotypical chinese cook of Blackhawk) and Blubber the Eskimo boy. So there was something in Eisner that responded to stereotypes of ethnics. And again, he was behind the times because other cartoonists (see Milton Caniff in Terry in the early 1940s) tried to portray the Chinese (although not the Japanese) in a more respectful way.

Noah wrote: “I didn’t mean that Eisner died a sinner and should never be forgiven. I meant that the racist caricatures in his work should not be excused or brushed aside in an evaluation of his work (that is, of the work in which they appear, not of all his work forever.)”

When evaluating exactly what it was about Eisner’s work that makes it special, I think the whole Ebony White issue is irrelevant. Now if you were doing a comprehensive essay about racial stereotype depictions in popular culture in the past 100 years, I think Ebony White would be fair game and very relevant.

Noah wrote: “The Japanese had (and still have, to some extent, like us) serious problems with ethnocentrism and imperialism.”

I call bullshit on this one.

First, the U.S. and Japan have almost no vestige left of the imperialistic tendencies both nations had in, say, 1900 – particularly when it comes to the desire to gobble up territory. One may argue that U.S. actions in Afghanistan and Iraq were “imperialistic,” but I don’t think so – at least not in the pre-21st Century traditional sense.

Second, while the U.S. still may be wrestling with some ethnocentric (and gender) issues, we are light years ahead of Japan.

Noah wrote: “Also, it’s simply not true to say that everyone at the time was equally culpable or equally to blame. There were people and artists around that time, even in the pulp field, who were committed to working against the racial stereotypes of the time. Moon Mullican, for example, recorded in interracial settings. Slightly later, Wanda Jackson had an integrated band, for which she took a certain amount of shit. Or there’s Artie Shaw. And that’s just white people; obviously folks like Langston Hughes (who wrote in popular venues) and Billie Holiday were much more aware of these issues (it’s kind of insulting to them to even put it like that, really.)”

Again, I think you’re going down a rat-hole here with your argument. The worth of Eisner’s contribution to comics has nothing to do with Ebony White. It’s a side argument related to a totally different issue.

Hey Jeet! Thanks for stopping by the new site, and for the thoughtful comment.

It’s interesting in light of Eisner’s own explorations of his ethnic identity — and maybe a reminder (in response to Mike above) that being Jewish really doesn’t make you any likelier than anyone else to be especially thoughtful about these issues.

I wouldn’t consider this a defense, but rather an observation- Jeet said “So there was something in Eisner that responded to stereotypes of ethnics.” Could this be related to the tendency in his cartooning towards exaggeration and theatricality?

Sean…I think that’s reasonable. Also I think, as I said above, comics history with this stuff is just terrible, even compared to other entertainment industries.

Still, as Jeet points out, even in the cartooning industry there were people who did better than Eisner.

Hey Russ. Japan’s imperialism has been strongly curbed by the fact that they have no military anymore — though I think there are still imperialist fantasies in their art, certainly. America’s imperialism is no longer about gobbling territory so much as controlling it; it’s economic and military hegemony, rather than territorial. I think it’s a similar impulse though. (Lots of folks on the right agree with me here as well, I think.)

The U.S. has a very honorable tradition of anti-racism and anti-imperialism. I don’t really know enough about Japanese culture to know how they compare there, honestly.

About Eisner, I think you may be misunderstanding me. I’m not claiming that his work is worthless. I don’t like it a ton, but that’s not really because of Ebony White per se. I’m open to the argument that Eisner is worthwhile despite Ebony White. That’s not exactly the argument Matt was making though.

It seems to me a lot of Eisner Jewish characters were pretty stereotypical too. Could the whole issue be a case of Eisner just not being good at character, thus drawing so extensively on the stereotype/caricature?

…And Sean beat me to it…

Yeah,Sean (and Derik) are right: Eisner’s racial stereotyping is related to his affinity for caricature and theatricality (wasn’t Eisner’s dad involved with the Yiddish theater?). This actually makes Eisner distinctive in a current sense: more contemporary cartoonists like Spiegelman and Ware tend to eschew the tradition of theatrical histrionic, preferring comics were the range of gestural expression is more muted. And, of course, as Noah says, comics have a long history of this. In part, I’d argue, because their is an affinity between caricature and stereotyping.

I think the formalist link between caricature and stereotyping is right. I think there’s also a historical issue involving the segregation of the American comics industry — a segregation which hasn’t entirely disappeared by any means.

Noah: Yes, I’m sure there are some in Japan who pine for the imperialistic days, but my gut feeling is that the Japanese, as a whole, would no longer stomach it.

Regarding racism, I lived in Japan from 1985-1991, and even that late in the game, some manga was being published with depictions of black Americans that were little more than stereotypical throwbacks.

I grew up in Chicago and lived there until I was 24, and Chicago was (and still is) a very diverse and multi-cultural city. That did little to temper racism throughout most of its history, but the fact remains that Chicago is very diverse.

Which is why, when I got to Okinawa, Japan, I was so surprised by how little diversity there was off of the U.S. installations. Of course, the (xenophobic?) fact that if you were not a Japanese citizen back then you could not own property may have had something to do with it.

The same seemed true during the year I lived in Korea in 1998. Koreans were everywhere, but little else. If you were a non-Korean, you were most likely an American assigned to a military installation there — even in big cities like Seoul.

In both places I often heard about the historical animosity between the Japanese and Koreans that apparently was still quite prevalent even during the 1990s.

So while some in the U.S. like beated us all over the head telling us how racist we are, the fact is that the U.S. is actually one of the most pluralistic societies on the planet.

I get that maybe some people were “better than” Eisner, but Eisner was simply part of popular culture in a day when such broad cultural and ethnic stereotypes weren’t such a big deal and were often used to create stock characters and maybe it took some people longer to read the changing times or to give up such easy stock types that could easily be used to create broad comedy. These stereotypes and characters just weren’t seen to be as big of a deal as we see them today in partly the same way my 60+ year old mother has no problem attributing parts of her personality to genetics/country of origin but I just don’t see it. It’s not PC for her to say it but I don’t think it’s outright malicious racism either.

Also, it’s interesting how many whites are so shocked and appauled at these caricatures and stereotypes yet many black people now collect such memoribilia. Sometimes these conversations seem to be more about white guilt that anything else.

On P’head Wilson— Actually, the question of where the baby-switched child/man gets his distasteful personality is not as clear cut as Noah makes it. One of the interesting things about the book is how it is ultimately (I think) undecidable if he is rotten because of his race/biology or because of the way he is raised as a “master of slaves.” Twain is known to be anti-slavery and anti-racist so it’s perhaps assumed that the question is clear cut by some…but having taught the book (years ago now) and thought about that very question quite a bit for classroom reasons—I don’t think it’s quite so clear. Biology, for instance, is what identifies the baby-switched boys as switched—Wilson has a record of everyone’s fingerprints as a hobby (a relatively new thing to do at the time the novel was written–to take fingerprints). There is also a “twins” subplot which might give credence to the “nurture over nature” element of the novel–but that subplot was intended for another novel and grafted on somewhat incongruously (or perhaps the choice to graft it on is significant). So… I’m not saying Twain is not “anti-racist” in many ways, but that book (and Huck Finn) actually have their racist moments–and might be considered to partake of racial stereotypes as well. The Twain/Eisner comparison doesn’t hold because Eisner makes no pretensions for the Spirit to be an anti-racist strip (or to be publicly anti-racist himself). Twain has that quality, but that doesn’t mean his work doesn’t have some racist elements…even in P’head Wilson.

As for Conrad’s critical fortunes. H of D is taught as much as ever, if not more, thanks to its amenability to some of the more recent iterations of literary criticism. Achebe’s is basically a lead-volley (or one of…) in treating the work in a “postcolonial studies” context…But that context hasn’t eliminated Conrad from critical interest—Just the opposite. It opens up “new ways” of thinking about and discussing Conrad. The notion of “universally great” works of literature is all but dead anyway in academic circles…so the fact that the racism in the book weakens its artistry as purveyor of the universal human condition is kind of irrelevant. It’s still a great book to read and study, both for its politics and for its aesthetics. (Students tend to hate it though, admittedly). Edward Said’s discussion of Conrad is also important in this regard..since Said is one of the lead voices in postcolonial studies (or was, before his death). His focus on Conrad definitely made H of D (along with The Tempest, Robinson Crusoe, Jane Eyre, and Kim) one of the most important of the “big monuments” of Western literature that must and do undergo interrogation from a poco studies perspective.

I think Achebe has some important things to say—as Conrad definitely does portray his Africans as subhuman…but Achebe pretty much ignores the degree to which the book is an attack on imperialism, colonialism, and capitalism. In the end, the most “savage” figure in the book is Kurtz, a white man–and so, if anything, the idea is more along the lines of how all humans are “dark,” corrupt, savage, stupid, greedy (or, possibly, how capitalism and capitalist exploitation make us so). The problem Conrad has is in using the African natives as a metaphor for that potentially “universal” tendency–using black Africans to signify a more metaphorical “darkness” and “savagery.” There is some evidence in the book, though, that the Africans are only “savage” because of their mistreatment by the colonizer, so it’s a bit more complicated than Achebe allows. In the end, though, I do think there’s enough in H of D to suggest that it does have racist portrayals of the African natives–but the attack on imperialism is also present, which complicates Achebe’s fairly straightforward attack. Said’s essay on Heart (in the book Culture and Imperialism) is more attentive to the complexities of the issue.

Twain is more a parallel to Conrad in this regard than to Eisner—as both have racist qualities and anti-racist qualities…while The Spirit’s racist qualities are not balanced by a passionate attack on racism….

As for Eisner being boring…I’m not so into his work, although I do see the formal attractions of The Spirit. One thing that is prevalent throughout the work, however, is a preoccupation with bondage, masochism, and submission to powerful women. Given your Marston interest, Noah, you might be intrigued by this recurring theme. I have a student who’s writing a thesis about it, and it makes The Spirit more interesting to me.

There’s a good chapter on The Spirit in Robert Harvey’s book, The Art of the Comic Book, which at least explains what all the fuss is about in regard to Eisner.

Russ, no one doubts that the U.S. is more pluralist than Korea or Japan. Being pluralist doesn’t obviate racism though. I live on the south side of Chicago now, in Hyde Park, probably one of the most integrated communities in the country. Yet the south side’s educational system and housing remains incredibly segregated and racist.

Pluralism can increase certain kinds of racism, is the point. America’s racial idealism is a great tradition, but it doesn’t negate America’s racism. The two often exist side by side.

Joe…you need to see Bamboozled. Beyond that…the ethnic caricatures you’re talking about were part and parcel of the nadir of american race relations. They tied into and were used to promote an ideology of white supremacy. They weren’t seen to be as big a deal because people didn’t think black people were human.

They are part of the history of African-Americans in this country, so I’m sure there are some black people who are interested in them. Often it’s in the context of critique, however. However, seeing that as an endorsement seems simplistic.

It’s a little depressing that this is still even an issue, I have to say. Eisner repudiated his own racial caricatures. So did Herge. If they can do so, why is it so hard for their fans to admit that this was not ideal?

Oh…and I should reread Puddinhead Wilson. I do think it’s awesome…but it makes sense that it’s racial idealism is tempered with a downside.

What you don’t see anymore, though, Eric, are treatments of Conrad that avoid poco interrogation altogether. You point the racism out, you qualify the “appreciation” — it’s that very characteristic academic ambivalence.

Maybe such an ambivalent treatment is all Seneca is calling for, but it doesn’t sound like it, and that approach is problematic in a popular context — witness Gary Groth’s critique that academics don’t make it clear whether or not they admire a work.

This kind of sentence, from Matt’s review: “The Spirit, especially the late-’40s run this panel’s pulled from, is one of the very best comics of all time, period. As an example of sustained artistic brilliance, of formal innovation, of serial narrative, it’s close to peerless.” I just don’t think you could get away with saying that about Heart of Darkness now, but I’m sure you COULD have prior to 1975.

Mistah Eisner-he dead.

Apologies if this is referenced above – don’t have time to read the thread carefully – but here’s an excerpt from a blog post in which James Smith recounts confronting Eisner over this issue (full post is at: http://tilthelasthemlockdies.blogspot.com/2008/04/false-hero-worship.html):

“As it happened, I had the opportunity to ask Eisner about this both one on one in a hallway conversation, and later at a panel sponsored by the convention folk. In the personal conversation, I quickly came to understand that he’d been asked this question quite a number of times and that he was a bit weary of it. But he sighed and hemmed and hawed and finally gave me the following excuse:

“Those were different times.”

Indeed. I know those were different times. My own parents were victimized for not succumbing to such racist thoughts and images and for standing against them in their southern community. I was well aware of the “different times”, and I was also aware that not everyone took part in such moral crimes. But our conversation was at an end and he wandered off.

Later in the day, at the panel, I was determined to ask him if he was at least sorry for the way he had portrayed Ebony White. I raised my hand a number of times and there were always others doing the same and being chosen. But I kept at it. Finally, a young man—a black man—raised his hand and asked the specific question I wanted to pose.

“I find the character of Ebony White to be very offensive, Mr. Eisner. Are you sorry for the way you portrayed him?”

Eisner was quiet for a while. After a bit he muttered the same thing about those having been “different times”. The man who’d asked the question asked again.

“Yes. But are you sorry for the way you drew Ebony White? To look like a monkey?”

Eisner lowered his head, considered for just a second, and said, “No.””

Whoops! Well so much for my crediting him with having gotten more thoughtful about these things. What a schmuck (as my people say — and his!)

I’m pretty sure Herge would have answered “yes.” And if not I probably don’t want to know!

Bah – the commenting system included a parenthesis and broke the link to Smith’s full post – here it is again: http://tilthelasthemlockdies.blogspot.com/2008/04/false-hero-worship.html

Noah: the whole thing is unreadable, believe me.

As for “different times” I heard that one when I mentioned Hergé’s racist imagery. Someone said that I needed to contextualize it, so I did: “at that time there were lots and lots of racist people and Hergé was one of them. Contextualizing complete.” Same goes for Eisner… Whitewashing by the usual team comics notwithstanding.

I’m a little skeptical about the caricature/stereotyping business. It’s obviously not wrong to recognize the relationship, but it’s also not an answer. If you can’t caricature without stereotyping, then how valuable is the distinction?

Coincidentally, this happens to be the explanation that the Obama Nation cartoonists are invoking against charges that their recent cartoon of the Obamas is racist:

http://bigjournalism.com/hudlash/2011/02/15/our-response-to-the-cartoon-controversy/

I’m not suggesting they’re wrong, just that it kind of avoids the point. Maybe there’s also a related problem with caricature…

Yeah, I think my response to that would be that political cartooning is a largely worthless art form that has to its credit two and a half centuries of failure.

Caro,—point being that the kind of academic critique which merely and only sings the praises of a work’s aesthetics is mostly gone…esp. for texts where that kind of praising has been so thoroughly “done” as in Conrad’s case. Still–plenty of people are willing to defend Conrad’s racial politics (claiming Achebe got it wrong)–and to claim that his formal strategies are part and parcel of a more laudatory politics. Praise for Conrad has not disappeared–nor has praise of literary works in general in the academic world. Often things are praised for their politics–but also for their aesthetics. Admittedly, the “job” of an academic critique is not, typically, to “recommend” a text, or point out its brilliance…but, in many cases, praise or critique is pretty clear. People have defended Conrad explicitly against Achebe on the basis of aesthetic grounds (see the Norton edition of Heart for some examples). Groth oversells his argument, though, admittedly, there is some element of truth in his claim.

One useful point to make is that H of D and The Tempest have been so thoroughly explicated and praised over the years, that it’s hard to know what else one could say about them from a purely aesthetic/formal perspective that hasn’t already been said. The political/racial/social angle keeps the texts alive in critical circles at least partially because that is what is left to say about them (although increasingly those avenues too seem exhausted).

This might also help explain why criticism of comics may be overly focused on the formal. Particular monuments of comics history have been discussed in terms of formal and aesthetic concerns–but there is still much to say about them in those terms in many cases. Critics of The Spirit can still explicate/explain its formal innovations because those have not yet been completely exhausted…and since people are talking about The Spirit (or whatever other example) because they like something about it…they’re more likely to talk about what they like. Most academic interrogation begins because somebody likes something…They may see problems with said aesthetic object, but usually people won’t devote months/years of their lives to exploring/uncovering texts or objects that they detest. There are exceptions to this, of course…but I do think, in general, that that is true. Given that, it seems natural to focus on that which attracts you (form, in this case) and not that which repulses (racial stereotypes)— Eventually, though, these things inevitably come to the fore, especially for texts that become canonized. Once H of D hits “sacred cow” status, it invites an ideological critique insofar as its status means it is taught and disseminated and read. If someone sees its dissemination as dangerous, then it’s more likely to be attacked ideologically (why attack something with no cultural importance?)–

So, the treatment of Eisner follows a well-established critical trajectory. Someone canonizes it on aesthetic grounds…once it’s a sacred cow, it’s time to point out and elaborate on its ideological failings (as we are doing here). I don’t see this as a problem necessarily–but given the nascent state of comics criticism, it’s no real shock that treatments of Eisner’s form are not exhausted…nor is it a shock that interrogations of its ideology are underway.

DC’s Best of the Spirit includes no appearances by Ebony White. So…Ebony is not whitewashed, but the book is.

Eric — I think this is almost entirely a question of inflection and emphasis ’cause I really don’t disagree with you. When I compare the way pre-theory Literature talked about HoD and the way Literature talks about it now, I think there’s been a greater drop in its standing than for books that have less of this particular kind of baggage (like, say, Ulysses or Invisible Man). It’s not reviled, by any means, but I think people are more suspicious of it. The interrogation is just a little more heated.

But beyond that I think my emphasis is just different. Take this: “the ‘job’ of an academic critique is not, typically, to ‘recommend’ a text, or point out its brilliance…”

This is completely right, but there was a time in the history of literary history where academics did consider pointing out the brilliance of a work to be part of their mission.

So what if a critic wanted to make such a claim, say in the kind of extended for-the-public article that Trilling used to publish in the Partisan Review or Kermode in the LRoB? Other than the fact that it wouldn’t help you get tenure, what’s stopping you?

Part of what’s stopping you, especially in cases like Heart of Darkness or The Spirit, is postcolonialism. Questionable representations of marginal groups aren’t something critics get to set aside when we look at a work. It’s a mark that you have to deal with. Texts that don’t have that mark are vastly easier to love — and to canonize.

(Of course as Suat points out what I originally wrote assumed that The Spirit wasn’t canonized, per Matt’s assertion, so my original formulation totally doesn’t fit this specific case anymore…but moving right along anyway.)

Your argument aligns with the one that Ana Merino made in response to Gary — that selecting a work for academic scrutiny is a signal of somehow appreciating that work. He didn’t buy it. He’s got a committment to evaluation that academics don’t have anymore — to the idea that a critic should possess an overt, acknowledged aesthetic agenda, and that criticism should measure art against that aesthetic agenda.

So in that context, the degree of enthusiasm you have for a “marked” work can cast your aesthetic agenda under suspicion. I made a quip on this blog about this, saying that I didn’t think Merino did a good job of arguing against Gary’s position, and one reason I think the argument you and she make isn’t enough is precisely this issue — academic ambivalence in some respect is a shell game that allows academics to avoid confronting the difficulty of formulating an aesthetic agenda at all in a critical landscape where considering a pluralist perspective is de rigeur.

The difficulty of dealing aesthetically and critically (in the old fashioned sense) with marked texts lurks in the ambivalent “interrogations” of academic reading, but ultimately, I think there is a broad aesthetic agenda in academic literature, one that requires a self-consciousness of these issues on the part of the text itself. But we have not been at pains to address this directly in aesthetic terms, so the places where aesthetics and theory collide are largely elided in academic writing.

In that hybrid popular/academic context like the one Gary loves so much, where overt evaluation and an aesthetic agenda just aren’t avoidable, this problem of dealing with “marked” texts becomes much more pronounced and difficult to finesse. Even in comics circles where canonization isn’t at all outdated a practice, it’s harder for a marked book.

Matt seemed to be calling for a kind of critical canonization of this book that would require comics to take a really iconoclastic aesthetic agenda — one that does not demand pluralist consideration of the representation of race. I think that’s impossible to sustain, I think. I just don’t think critics would be able to successfully canonize anything that requires this kind of justification, even if the work really deserved it on formal grounds. The problem of racial representation is just too mainstream.

Hah! I’m always telling Eric he’s too mealy-mouthed about these things!

Ebony White (a joke!, get it?) isn’t the only problem with _The Spirit_. The characters are cardboard and the stories are trite. Eisner at his best (worst?) was kitschy and sentimental (e.g: Gerhard Shnobble).

How about misogyny, by the way? http://tinyurl.com/68o2n3m

Domingos, if you applied the same artistic judgment criteria you use to critique Eisner to your fine art heroes, you wouldn’t have any heroes left.

Question: Was Rembrandt a misogynist?

Answer: Who the hell cares?

Question: Was Michelangelo a racist?

Answer: Don’t make me repeat myself, muttonhead!

Question: Wasn’t the subject matter for Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” painting trite?

Answer: Subject matter? Are you nuts? Look at that brushwork!

Question: Don’t the people in Da Vinci’s “Last Supper” look posed?

Answer: Who cares about the poses? It’s a masterpiece of design!

One of the foundation principles of cartooning is caricature. Stereotypes, whether they be soccer moms, republican blowhards, Italian mafia types or thick lipped blacks are part of that. In order for a stereotype to be racist (as opposed to racial) there has to be evil intent behind it.

The history of cartooning has several under appreciated geniuses… Eugene Zimmerman, Will Eisner, Milton Caniff… who interestingly enough were recognized as such when they were alive, but have fallen in popularity only in reconsideration. Ironically, the people who label them with the term “racist” usually are the ones who only look at the surface of the work, and don’t have an understanding of the real reasons why these artists were the leaders in their field.

Will Eisner was not racist. He was a cartoonist using stereotypes that were familiar to audiences of his time in a largely sympathetic way. Ebony was a character intended to supply a character that younger people in his audience could enjoy and identify with. As such, he serves pretty much the same purpose as Billy Batson. But the real heart of the Spirit is the masterful drawing, the film noir settings, the brilliantly designed splash pages, the great business acumen of creating a self owned strip for newspaper supplements, and the overall adult feeling of it compared to the one dimensional “underwear heroes” that were the norm at the time.

Stephen, I just find this to be complete and utter nonsense.

“In order for a stereotype to be racist (as opposed to racial) there has to be evil intent behind it.”

That’s really wrong-headed. The issue isn’t what Eisner intended. The issue is what he created. Part of what he created was a surface. That surface is a disgraceful racist caricature that employed white supremacist imagery to paint a black character as a figure of mockery.

You want to say that there were wonderful formal elements to the Spirit? That’s fine; an utterly reasonable thing to say. You want to argue that Eisner (and his studio assistants) were innovators? Again, perfectly reasonable argument. You want to say that the heart of the Spirit is that formal innovation? That’s a reasonable opinion.

But the fact that Eisner was talented and innovative doesn’t change the fact that he created a racist stereotype (or a few of them) and put it at the center of his work. It doesn’t change the fact that that’s a really morally problematic thing to do. And when people look at it and say that’s racist — that is not the fault of the people doing the looking. It’s Eisner’s fault because he made a fucking racist image and used it in a racist way in his comic book.

If you like his work, you like his work. There’s a lot to like; I can see that even though I’m not really a fan myself. But pretending the racism doesn’t exist and then sneering at people who are bothered by it — I’m sorry, that doesn’t wash.

And you know what? The fact that it was better than the underwear heroes? Nobody cares. Why not just dig a hole for the bar before you jump over it, huh? (And it isn’t necessarily better than a number of them either; not better than Wonder Woman, damn it.)

Sorry — I know this comes off as fairly aggressive. But I just feel it can’t be okay to tell people who don’t like Ebony White that the problem is that they are philistines. It’s embarrassing to even make that argument. I beg you to think it through again. Eisner can be great despite his racism, but making excuses for the racism, or blaming the people who point it out, is dishonorable — not least to the work itself.

Just one more thing:

“Will Eisner was not racist. He was a cartoonist using stereotypes that were familiar to audiences of his time in a largely sympathetic way.”

The stereotypes of that time were racist. Black people were treated really crappily in this country. White people didn’t believe they were human. One of the ways they showed that and arguably reproduced that ideology was through images like this. Eisner reproduced the ideology uncritically, though other cartoonists at the time, and other artists at the time did not. That doens’t make him irredeemably evil. It means though that he trafficked in racist imagery. And people who point that out aren’t fools. On the contrary, they’re right.

Russ, are you just generally uninterested in content?

I mean, I’m interested in Rembrandt’s portrayals of women (John Berger has a nice discussion of at least one picture); I’d be interested in how Michelangelo delat with race, if he ever did; Van Gogh’s triteness is a reason he’s not one of my favorite artists (though I do like him); and I kind of like the stiffness of the Last Supper — it seems like part of the point. All of the issues you raise seem valid and even interesting. If they aren’t the things you want to talk about, that’s cool, but it seems odd to assume that anybody who did want to talk about them was misguided or foolish. If art is great or interesting, it seems like it should be able to engage a lot of perspectives or conversations. It seems odd to insist that there’s only one thing to say about Da Vinci, or about Eisner, for that matter.

“I’m not suggesting they’re wrong, just that it kind of avoids the point.”

If they’re right, what is the point that they’re avoiding?

I’ve been a fan of Eisner since about 1972 or so, and while I dutifully read all “The Spirit” reprints I could lay my hands on, Eisner’s dialogue, and the “depth” of his characters never really interested me.

What I really captured my attention was how Eisner moved his stories sequentially (including the masterful way he was able to manipulate time for his audience), and how he created a then-unique noir universe that had character, mood and a depth that only a tiny handful of cartoonists before him had been able to convey (McCay immediately springs to mind).

I never really cared about Ebony, Ellen, Commissioner Dolan, P’Gell, or most of the other characters. They were so shallow they were almost like props to move Eisner’s “film” along. Even the Spirit was merely window-dressing in some stories, standing Watcher-like in the background while the story rolled along.

In this regards, I viewed the best installments of “The Spirit” as I did Fritz Lang’s film “Metropolis.” The visuals and flow enthralled me, but I did not care a whit about the two-dimensional characters in either.

THAT’S why when I examine the artist merit of Eisner’s work, I don’t CARE about the whole Ebony issue, or whether or not Eisner was a misogynist, etc.

I just don’t think it’s relevent.

It’s an entirely formalist appreciation, then.

That’s kind of where I”m coming from with Winsor McCay. McCay doesn’t have any pretense of telling pulp stories though; it’s all dreams and fabulous fantasies — there aren’t even pasteboard characters, often. It just seems more self-consciously hollow; the content is the absence of content for McCay, so I don’t feel I have to trip over the fact that it’s so empty-headed.

Eisner’s hollowness seems less thematized; more just conventionally vacuous. Which doesn’t mean you can’t just enjoy the formal elements, but I think explains why I haven’t ever been able to do that in the way I can with McCay’s work.

I’d say there’s a sliding scale to racism, and that while Eisner’s using racist imagery, it’s possible that the effect of the character wasn’t completely racist. I find his stuff pretty dull, too, but if it’s true that Ebony is one of the more nuanced character’s in the comic, then that could be a way of moving away from racist ideology at the same time as participating in it. I think this is what occurred to some degree with getting whites into black music via blackface and, even, the imagery used to sell someone like Leadbelly. And a similar argument could be made about Amos and Andy. Getting over racism isn’t some line that needs to be crossed, but a gradual shift in attitudes about a whole variety of things.

Tom – the question of whether the exaggeration that they claim is intrinsic to caricature is linked to stereotype in a way that casts suspicion on caricature itself.

Or, more broadly, Jeet talks about the “affinity between caricature and stereotyping”…what exactly is that affinity, in formal terms, and at what point do they no longer hold hands?

If it’s just a historical association, it’s not a justification for caricature that trafficks in stereotypes, because that would imply a formal separation, the availability of formal choices that result in caricature but not stereotype. But if it’s more than a historical association, then what makes one caricature of a given object a stereotype and another not a stereotype? If there’s a formal association between caricature and stereotype, how do you tell the difference?

The problem with the common answers to that — context, intent, external social reference — is that it becomes arbitrary: “one man’s caricature is another’s stereotype.” That’s that same quagmire of ambivalence…the flattening and equalizing of all perspectives, with no committed aesthetic (and in this case, also socio-political) agenda.

I think it’s worth avoiding a situation where people can defend any cartoon stereotype on the grounds that it’s “caricature.” If our theory of caricature allows for that, we aren’t done yet. We should have a way to respond back, “no, that isn’t caricature; that’s stereotype.”

Stereotypes, like the ones I show in the image linked to below, or other familiar shorthand images, have historically been a crucial part of the cartoonist’s communication process to his/her audience.

Stereotypes are a kind of shorthand that the audience can understand with little or no extra explanation. Some are designed to strike a universal chord where the collective audience knows, on sight, the established characteristics of the stereotype.