Interview: CF x Matt Seneca

If I had to pick a creator who best exemplifies the present moment in the comics medium, it would be Christopher “CF” Forgues. CF’s work encompasses the bleeding-edge immediacy of the most innovative art-comix while retaining the universal themes and broad appeal of classic genre, creating a space for itself that can’t really be forced into any of comics’ established stylistic categories. There’s a nearly unparalleled intensity of personal expression to his pages, but the elegance of CF’s graceful, delicate pencil lines and the bold directness of his design and color sense often completely transcend the subjective, calling up an archetypal feeling of comics’ essence, as well as a roll call of the medium’s past greats. As a visual stylist, CF is massively influential; echoes of his emphasis on harmonious forms and his use of raw, unadorned pencil and paint as drawing tools are visible in recent work by many promising newcomers to the field, not to mention a few old masters.

It would appear that, like Chris Ware and Gary Panter before him, CF is being absorbed by the comics medium itself, the particular language he uses the form to create bleeding from his books into the general idiom of comics shorthands and techniques, pointing toward the way of tomorrow by inventing the way of today. Coming off a star showing in his most recent graphic novel, Powr Mastrs 3, CF has transcended influence and inflection, reaching a purity-in-comics that only a handful before him have; but there’s also a distinct sense that his best work is still ahead of him.

CF is one of our most articulate artist/talkers, a fascinating explicator of his own work and of the medium in general. I was thrilled to interview him, and I hope you’ll enjoy reading what he had to say.

*******

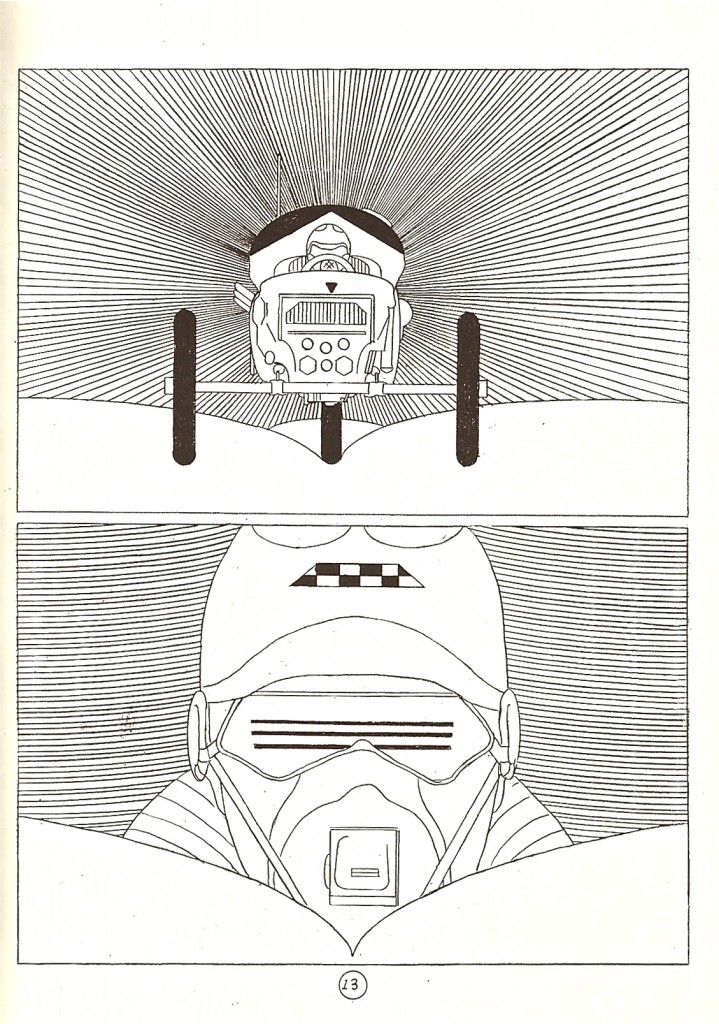

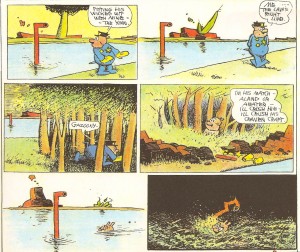

From Powr Masters 3

MS: So, you gave a pretty rousing slideshow presentation on the book release tour for Powr Mastrs 3. One of the things you mentioned that I was most struck by was that drawings can contain different forms of energy. What are these energies, and which ones do you try to make a part of your work? Do the drawings capture them or create them?

CF: Drawings of course can have energy of any kind… every drawing is an evocation of a spirit, not really “capturing or creating” but manifesting, more like “both”.

My work is investigating where these different energies meet in familiar and unfamiliar places, and the moments or places in which they transform. Looking at these things teaches us about our work, our loves, everything, what we have to do right now in our lives. Nothing is inadmissible evidence, I try to look at “everything”.

MS: Have the energies your work is manifesting been manifested by comics before? Are there any artists whose work you look at for inspiration along those evocative, totemic lines? Anyone who you want to capture the same energies as?

CF: All creative work is about energy, so yes, I would say every comic and more has explored these things before. Some cartoonists you can feel a lot of shapes in: Kirby, Herriman, Mazzuchelli, Gould. When it comes to raw shapes I’m influenced by music a lot, many many underground bands, pointless to list. Just a few artists that impress me in this way are Frank Stella, Morris Lewis, Tony Smith, Lawrence Weiner.

MS: There’s been a tendency toward the abstract in your work for a long time, but in the new Powr Mastrs it seems like it’s taking a more prominent stage, both in the penciled and painted sections. Is that accurate? What do you hope to achieve with your abstract, shape-based sequences as opposed to your more representative ones?

CF: Well, all cartooning is an abstraction. Cartoons tend to be easy to relate to because the character’s personalities and appearances are (at worst) reduced or (at best) refined to an abstraction. So there you have Andy Capp or Charlie Brown. I guess to me these things are already happening in cartoons so it’s not such a leap to employ the whole toolbox of shapes. These shapes are literally universal, and can speak to ideas or feelings that are “beyond human” or maybe “beside or beneath” human. I’m not sure what the most appropriate preposition is there, ha ha.

Our response to these things can be visceral, nonverbal, or hardwired from ancestral memories and associations. I believe these shapes have a power that’s inherently cosmic. Shapes go right to the heart of mystery. The basic things a shape can represent… numbers for instance…. these things seem to be indestructable, principles that were here before us and will be after we are gone. “1”, “2”… these are ideas so basic it’s hard to escape them. We barely can see them as ideas but they are. In that way they are “the ultimate”. However, they are also very mundane, and even boring, “nothing special”. We are surrounded by them everywhere we go, in buildings, clothing, furniture and of course in nature. So the spirit world is the normal world too.

I use elements like this in a story to talk about states of mind and being that are not so easily explained with a normal representative signifier. To me it’s not much different than the stars when someone gets hit, or a cloud when someone’s supposed to be depressed, it’s just a bit more exploded on the pages, and a bit more obtuse. The difference is, these shapes are the subject and the object simultaneously. In this way they remain accessible — you see a square, and that’s it… there’s nothing more to understand.

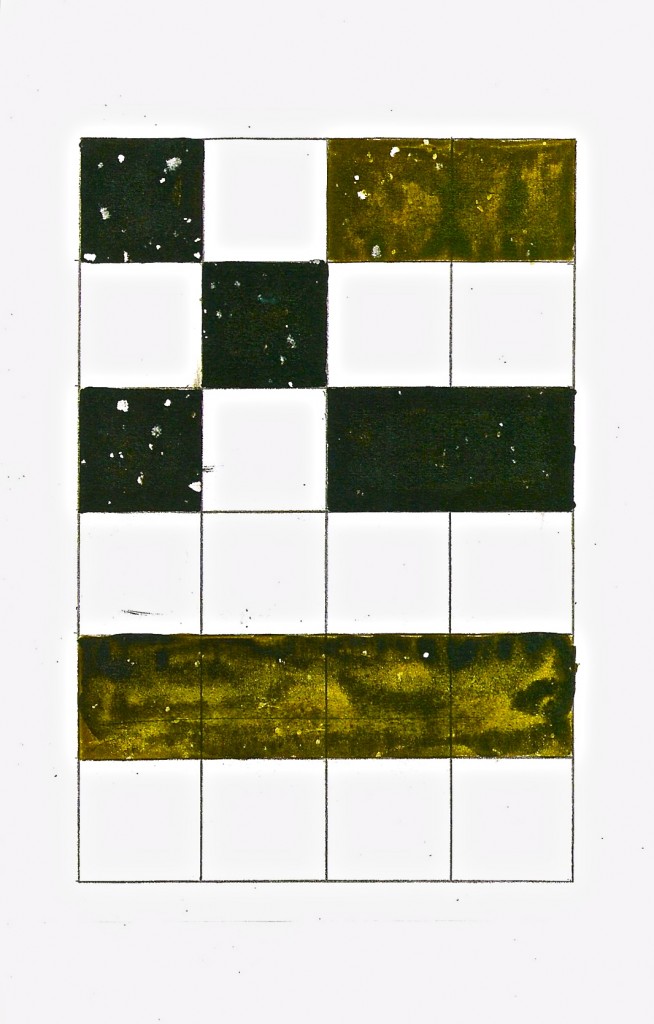

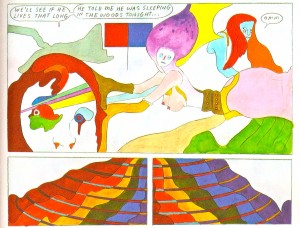

An abstract page from City-Hunter Magazine

MS: Those more obtuse meanings your shapes and marks carry — they’re not yet agreed upon in the way comics readers instinctively know what pain-stars or depression-clouds mean. Still open to interpretation. Do you think there’s any common effect they produce across the spectrum of your readers, or do you think everyone will take them in totally different ways?

CF: Getting hit on the head is a pain we feel on the surface of our body. There are other pains too, harder to describe, but it’s tedious to assign meaning; meaning already exists on its own. These forms talk in a mysterious way to everyone, you can call it unconscious, intrinsic, or ancient. But like I said, it’s nothing special. What makes it so mysterious is that it’s so obvious, so plain. It’s so simple that it seems hard to penetrate, but actually it’s just what it is, very simple, sitting where you left it before you started to try getting clever. Just a triangle, or what have you. To me, that’s the mystery of life!!! Ha ha ha.

MS: Do different shapes hold more or less meaning, or more or less powerful ones? If simplicity is what gives shapes their importance, what about more complex shapes? I was especially noticing how the “Black Tarp” sequence in your new book starts out with very intricate forms and then simplifies itself down until only squares and emptiness are left on the page. Do you think there’s a greater appeal to simple shapes?

From the “Black Tarp” sequence in Powr Mastrs 3

CF: Everything has its purpose. It’s not that simplicity gives shapes importance, it just makes them more universal. Different things “appeal” at different times for different reasons, there is no one right way.

MS: How much storytelling potential do you think these abstract shapes have? To what degree do the meanings in them need the straightahead meaning of more relatable, figurative drawing in order to carry a narrative?

CF: Simple shapes can tell a simple story. Figurative and abstract create an electricity between them, between understood and not understood.

MS: You mentioned evoking spirits with your drawings. Especially in talking about shapes coding for more nonverbal ideas, my immediate thought is religious iconography and the way shapes like a cross or the lines of Islamic calligraphy (just to name two more obvious examples) can serve as visual conduits to the spirit world. Is any of your work explicitly “spiritual” in the meditative, rapturous sense of the word — designed to produce a transcendent effect?

CF: Everyone seems to be waiting to hear that I’m using intentional code parented by a world tradition of spirituality, numerology, astrology, cartography, whatever. The subtext is that this makes what I’m doing more valid or authentic, less a story about something, and more the thing itself. I don’t subscribe to this philosophy whatsoever. When I draw I open myself up, I’m not fully in control. I have to give up or nothing will happen. If I try too hard, I’m deluded, and I think I’m doing one thing when I’m actually doing another. This delusion is a lot of the world’s history of religion. If you want to feel the universe move through you, you have to make a space.

Imagine inviting someone over and taking their coat, then offering them snacks, then getting them a drink, then putting a blanket on them and putting their feet up for them and asking them if they’re comfortable, then telling them where the towels are and so on. By trying so hard to be a good host, you become the worst host ever.

So if I were to make a comic full of intentional occult (or what have you) references it would make my work “just a book” full of tools that aren’t mine, that I don’t know how to operate… I would look like a fool and I would deserve it. As it stands now, my work has dynamicism, and rings with a sincerity towards the “spiritual” exactly BECAUSE I have kept all this second-hand claptrap out of it. There’s me, the work, and a third mysterious thing. I’m not opposed to these things showing up of their own accord, I welcome it, but I’m not trying to make a show. The energy of the universe is (naturally) “universal”. It will power a swastika, a cross, or a gag cartoon. One is not necessarily better than the other, by which I mean the point is not the symbol — it’s what’s behind it, what’s “universal”. If someone is trying hard to convince you that their vessel is better than any other, they have a horse in the race… they’re a politician, police, or a baby brained baloney peddler. And they will continually be looking for victims.

Comics can transport people to another place entirely… if it’s done well, that’s transcendent enough!

MS: Is that abandon — that willingness to relinquish control and let the other things in the work speak for themselves — something that you try to employ in your use of comics’ picture-making tools? Are there tools you like to establish different amounts of control with?

CF: Pencil is very versatile. I only try to be sincere in the moment of the creativity — control is almost irrelevant in a way, or at least too complex to quantify.

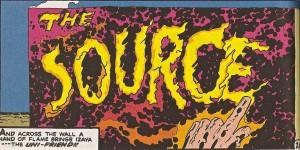

Kirby draws divinity

MS: You mentioned Kirby as an influence. Now there was a guy who really did use comics with the intent of creating hermetic, or even straight up religious texts. I think his raw abstract shapes definitely carry that telegraphing, spiritual power, but I think your analogy about being too good a host is spot-on where his attempts at more explicit mythology are concerned. He showed too much, explained too much a lot of the time. Do you have an opinion on how successful Kirby was at putting spirituality on the comics page?

CF: He certainly transmitted his deepest thoughts and feelings. I think his world was pretty black and white, or he wanted it to be. He seems to have had a burning rage for answers, and he asked questions on a monthly basis. Kirby had an acute sense of just who he was in life and in society, he had a great self-awareness. I don’t think he was trying to offer answers for all of time, it’s more like he was asking questions in a proud notebook series. He related to things in a big, bold way, and it comes through naturally on the page… the consummate American warrior.

MS: How about Herriman? Even though he was less overt about transcendence and spirit worlds than Kirby was, I think his shapes and spaces can often put across more meaning than Kirby’s. What hits home with you about his work?

CF: Herriman was a free spirit, plain and simple. He was nothing like Kirby, his whole angle of quest was different. His whimsy belies a patience and acceptance of ignorance, even a celebration of it. I think he had a keen sense of how small we all are, how little we actually know. His landscapes compete with the figures in almost every panel. You don’t need to read into his work very much to see that that says a lot. He could have drawn anything, but that’s what he drew… he was a very special artist, very generous and humble.

Herriman figures, Herriman landscapes

MS: You tend to ground all the comics pages you draw, no matter how far-out the subject matter gets, in relatively basic, simple layouts. What keeps the abstraction mainly in the pictures and less in the sequencing?

CF: Well, I am trying to make a readable comic after all. Comics are meant to be read. You can push, but you need to have something to hold onto or you’re not transported, you’re back in a chair, looking at a piece of paper, and you’ll lose a lot of readers that way because you’ve broken your contract with them.

MS: Color definitely plays a strong role in your work, but it isn’t something you use all the time. What dictates where you choose to use it and not use it? What purpose does it serve that your black and white linework doesn’t?

CF: There’s always a threshold to be played with in terms of how much we can tell an audience and still be understood. Some radio plays shine brighter than a movie because they leave things to the imagination. This is the basis of eroticism and a lot of religious tradition as well… “the unseen hand”. So it’s not always so great to use color. Also I find it refreshing to be reading in black and white, and then come to some color, and then go back to B&W. It reminds you in the story and in life that there’s more we could be seeing, or more to imagine than what’s in front of us. There’s things beyond color, too, that we can imagine.

It’s really American to think “more is better, lets do everything we can, all the time”. When I use it, it’s because “I’m inspired to”. Usually I “see” the colors on the drawings and it makes sense, so then I know to paint it. Ha ha — not a very good answer, but an honest one. Maybe I’m too ignorant to answer well. Some things look better in color!

Color panels from Powr Mastrs 2

MS: Your stories also carry more abstraction, or at least non-linearity, than a lot of comics, but they’re pretty much always still solidly narrative. Powr Mastrs, especially, seems to be shaping up as something of an epic. Is there a reason you’ve chosen to utilize narrative in your work? What about the form attracts you?

CF: I’m aware that there are young people right now trying to make moves in comics and deny the story, but comics are a storytelling medium, more or less. They can be poetic in the hands of one who “knows” (John Porcellino), but comics are designed to tell stories of some kind. So in a way you’re asking “why comics?”.

Stories are actually our history, our knowledge, our wisdom. We can’t live without them! Stories are unique in their ability to speak on many levels at once in a very intimate way. I’m drawn to that infinity of possibility. I want to talk about “everything” with my work, but in an elegant and economical way. Comics are perfect for this. So we have funny jokes, economics, significant and insignificant events, cruelty, violence, eroticism, death, and tranquility within one work. It’s a visual world, with exclusive abilities, living in time…. and still so simple. That to me is very beautiful. This is what comics are for… if I want to do other things, I make a painting, a sculpture, or music. There’s no excuse for abusing comics. Of course we can play with the idea of “story”, and I think that’s a great, worthy thing to do, but I want the characters and ideas to always remain legible within that experiment.

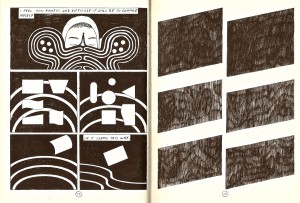

From Monster

MS: So how do the stories come about? It seems like Powr Mastrs is somewhat improvisatory, following more of an internal logic than a rigid set of plot points. How much do you compose the specifics of your stories before you start drawing them? Does a lot change in between the original idea and the finished page?

CF: Yes, a lot changes. It’s really funny when you’re young, because you think a great idea is all it is. You think if you can imagine something terrific it’s just a hop skip and a jump until the book’s done. Ha ha, but that’s not so, it’s hard work, and there’s a lot of ways to skin a cat; which one is the best? You can spend the rest of your life trying to find out.

Also when you prepare for a story, that’s one moment in time. By the time you’re finishing it, that’s another. So it’s always going to change substantially. But you can always hold the first moment, like that shudder when you see something for the first time, your first impression. There’s nothing quite like that undeveloped glance, that’s pure magic. And I try to keep that in mind as I develop something, big or small, whether I’m moving away from or towards it.

As far as composing stories, I get the major points or inspirations at the ready. Then I improvise to bring point A and point B together…. So you know you want to go from the apartment to the store, you know what to buy, you might even know what road you’re taking, and maybe you’ve taken it 100 times, but you never know what’s going to happen on the road, not really. Different stories have different amounts of freestyling in them.

I used to feel a little sad or embarrassed about working like that — i.e. “That’s not how real writers work”. But then I heard an interview with Cormac McCarthy, and he said his process was very similar, that if he knew everything about the story before he began, he would quit writing out of boredom. So making stories is a way for the author to learn. In a way I think this might be their raison d’etre.

MS: How separate are the characters from the ideas in your stories? Do you see your characters more as embodiments of abstract concepts, or as “personalities” that just do what they will — like, how rigid is the “logic” governing your characters’ actions?

CF: Certainly they are personalities and simultaneously embody abstract concepts as everybody does. They work to different ends, and on different levels at the same time, playing their roles to form a complete circuit. So you have a transistor here, a resistor there, a capacitor somewhere else… if one part moves, it changes the whole relationship and the machine works differently. Just very basic things like this. Basic, but potent. Maybe you’re trying to ask where they come from?

It’s not dogmatic if that’s what you mean. The characters represent themselves. I never tell them what to do, I don’t control them in the normal way of force. They each have their own logic and agree, conflict, or neither, or both. That’s pretty close to a logic gate, i.e. “if A, then C and G” “if C, then not B”. These nuances are not necessarily very predictable though, because it’s a complex mesh of these devices, all superimposed. And there is a random number generator in there too, so there’s chance. This is how creatures are made! And after they’re made they begin to fall in love, and that changes everything too, so you see it’s not so simple to bully characters into being what you want, and saying everything you think like a puppet. Like any good creator, you have to be patient and generous with them, and try to have some broad understanding.

Comments have been closed by request; read it again!

Pingback: Tweets that mention “You Have To Make A Space” « The Hooded Utilitarian -- Topsy.com

Pingback: Carnival of souls: Joyce Farmer, CF, Comix Cube, more « Attentiondeficitdisorderly by Sean T. Collins

Pingback: Secret Door Projects » delights of working