In which I blather on at length about the five-act structure and complain about a prologue. Plus a craft tip! You can follow along with the comic at http://www.elfquest.com.

You’ll have to forgive my lousy photos, as I’ve recently upgraded to 64-bit Windows 7 and Epson hasn’t put out a driver for that version suitable for my scanner yet, so a point-and-shoot camera it is.

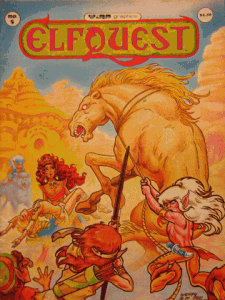

Issue #5 –“Voice of the Sun” Recap

This issue brings us to the end of the first story arc. When I think about it, it seems deceptively slight, but there’s a lot of story and denouement packed into its 32 pages.

This issue brings us to the end of the first story arc. When I think about it, it seems deceptively slight, but there’s a lot of story and denouement packed into its 32 pages.

It begins with the Wolfriders adapting to life in the Sun Village. Redlance’s tree-shaping powers finally emerge, and Skywise begins to greet the day with Sun-Toucher on the bridge where Cutter won his challenge. Back in a cave, Dewshine and Scouter, the two young lovers of the tribe, wonder at the physical and emotional toll that unfulfilled Recognition is taking on Cutter. The Wolfriders don’t understand Leetah’s viewpoint, that Recognition takes her autonomy away. He confronts her as she waters a zwoot, one of the Sun Village’s giant beasts of burden, attempting to persuade her that Recognition is like joining two handfuls of water into one. They’re interrupted by Leetah’s sister Shenshen and Cutter stalks off.

Nightfall offers her friendship to Leetah, because Leetah saved Redlance, her lifemate. Leetah asks her what a soul name is, leaving Nightfall nonplussed, when the Smoking Mountain, a distant volcano, rumbles.

Skywise, up on the Bridge of Destiny with Sun-Toucher, howls for Scouter to come. Scouter’s sharp eyesight discerns the riot of a zwoot stampede coming from the volcano’s base, stirred up by the volcano’s tremors. The Sun Villagers drop what they’re doing and head for the hills, to the mystification of the Wolfriders.

In the caves where the Wolfriders live and sleep, Cutter seeks counsel from Treestump, the oldest member of the tribe. Treestump is saying that he’s got reason to believe that Cutter’s troubles aren’t as bad as he thinks (a reference to issue #4, where Treestump spotted Leetah sneaking away from overhearing the tribe’s howl ), but is interrupted by the villagers. The Wolfriders who were down in the village explain to Cutter that when the zwoots stampede, a canyon funnels them right into the Sun Village, and they trample the crops and huts. Rayek has, in the past, tamed a few zwoots with his mental powers, but against the entire herd, there’s nothing they can do. Cutter complains that the villagers just let the zwoots trample their village without trying to stop them, and Leetah rebukes him, asking “What would you suggest, Wolfrider? A net?” – referencing what she head in Issue #4 – leaving Cutter confused.

The Wolfriders decide to turn the herd before it reaches the village. Dewshine arrives with rope she found in a hut, suggesting they catch a few zwoots. Leetah is horrified that Dewshine, a young and delicate maiden, would go with them, and Dewshine chides her with “*tsk* Shame on you, Leetah! Don’t you know your own mind about anything?”

The Wolfriders meet the herd, and harry the zwoots until they turn from the village, rejoicing in finally running free with their wolf brethren again. The Sun Folk take a lesson from this – that things don’t need to be accepted gracefully, but that you can change events if you choose to. Leetah confides to the elder Savah her conflicting feelings about Recognition. Savah explains that Recognition serves the elfin race by ensuring that the elves with the best qualities reproduce, and points out that while Leetah fears for her freedom, Cutter values his freedom as well, and that perhaps this may not be such a bad thing after all.

The Wolfriders call from the entrance to the cave. Several of them have caught a zwoot and are bringing it to Savah, who tames it with her mental powers. Scouter and Dewshine ride up, with a tired-out zwoot who suddenly gets a second wind and bucks, tangling Scouter up in the ropes that he was holding. Dewshine leaps to cut the ropes and is bucked off and knocked unconscious on a rock. Leetah acts without thinking, for the first time in her long life, rushing out and picking Dewshine up so she wouldn’t be trampled, running from the zwoot, until Strongbow drops it with an arrow to the head.

Leetah is angry at what happened, at first silently blaming the Wolfriders for not protecting Dewshine, but as the narrative says, the answer is in Dewshine – “She is not a child, but a Wolfrider, free to run and hunt with the pack as she wills!”

Leetah is angry at what happened, at first silently blaming the Wolfriders for not protecting Dewshine, but as the narrative says, the answer is in Dewshine – “She is not a child, but a Wolfrider, free to run and hunt with the pack as she wills!”

Cutter, distraught, offers to go away forever if Leetah will heal her, but Leetah cries that she doesn’t care what Cutter does, and takes Dewshine to her hut, where she heals her.

Later, after Dewshine awakens, Leetah watches her and Scouter, musing on their youth and her age – more than six hundred years – and feeling a loneliness in her heart. She asks where Cutter has gone, and Skywise tells her that he’s left, as Leetah’s made it clear that she doesn’t care if he stays or goes. Leetah calls him an oaf, and runs after Cutter, as Skywise smiles slyly.

When Leetah catches up to Cutter, she walks with him a while, chatting uncomfortably. Cutter says that he knows Rayek would be better for her, and she rebuffs him, telling him not to think for her. Cutter confesses that he can’t live without her, that for him, Sorrow’s End is Sorrow’s Beginning. Leetah then speaks his soul name for the first time, and embraces him. She says that now she has spoken it, she knows what a soul name is – that the one simple word encompasses all of his being. Cutter admits that he searched for her soul name, but couldn’t find it. Leetah reminds him that except for Savah, the Sun Folk have mostly forgotten how to send, and that they don’t need soul names to guard their private selves from others. As they banter, Cutter places Leetah on Nightrunner, his wolf, who takes off running, with Leetah on his back.

Later that night, Cutter arrives at Leetah’s hut. Wordlessly, she emerges, with a blanket. Together they walk in silence to the Bridge of Destiny, where the consummation of their relationship is marked with a single, sent, “Yes.”

The next day, Savah sends to Rayek, who is far away from the village, and tells him that Cutter and Leetah have become life-mates. Rayek muses that it was unlike Leetah – he’d thought that she’d have led Cutter around for at least a year. He tells Savah of his intention to leave. She mentions that in the past, others in the Sun Village have taken more than one mate, but Rayek dismisses that suggestion as he rides his zwoot out into the desert, saying that he will find his place, which is not in the village.

That evening, the Sun Folk and the Wolfriders hold a festival, celebrating the union of their tribes, and the issue ends with several Wolfriders showing Cutter and Leetah their present – a dreamberry bush grown by Redlance from seeds that Pike stuck in his pouch as they left the Holt.

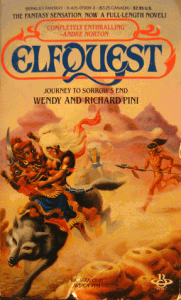

Elfquest: Journey to Sorrow’s End

Consider yourself saved: I’m not going to recap the novel here, and instead direct your attention to my previous columns, if you’re forgotten the plot. :) The novel was published first by Playboy in 1982 and republished by Berkley Books in 1984, which is the vintage of my current copy. I must have either bought it at or brought it to the Quest’s End con in Austin, TX in 1984, as it’s signed by both Pinis. I had a copy of the Playboy edition that fell apart due to multiple rereadings; I remember attempting to glue the pages back into the spine of the book with a bottle of Elmer’s Glue I’d dyed green some time previously, so it was an awful-looking but well-loved book.

Consider yourself saved: I’m not going to recap the novel here, and instead direct your attention to my previous columns, if you’re forgotten the plot. :) The novel was published first by Playboy in 1982 and republished by Berkley Books in 1984, which is the vintage of my current copy. I must have either bought it at or brought it to the Quest’s End con in Austin, TX in 1984, as it’s signed by both Pinis. I had a copy of the Playboy edition that fell apart due to multiple rereadings; I remember attempting to glue the pages back into the spine of the book with a bottle of Elmer’s Glue I’d dyed green some time previously, so it was an awful-looking but well-loved book.

(To dye glue: Disassemble a felt-tip marker. Snip off a length of the felt nib and drop it into a bottle of Elmer’s Glue. Let sit for a few days, and the color will diffuse through the glue. Et voila!)

Discussion

The one thing that’s bothered me for years is that on the cover of issue #5, Strongbow’s got his arrow on the wrong side of the bow! (Which I know is definitely correct, despite the idiot who attempted to mansplain the wrong way to shoot at ten-year-old me at a Renaissance Festival and refused to shut up even when I pointed out that I had been shooting for two years and owned a compound bow of my own! Cue outrage over my choice of terms.)

The issue is almost all dénouement – the first story arc seems to follow a classic five-act structure: Issue #1, the introduction of the Wolfriders and their quest, #2 rising action as they find Sorrow’s End and Cutter and Leetah Recognize each other, #3 the action climax as Rayek challenges Cutter (with the final result of that challenge right at the beginning of issue #4, as issue #3 needs to end on a cliffhanger, not a resolution), issue #4 the falling action as Rayek leaves and Leetah eavesdrops on the Wolfriders’ howl, and #5 the dénouement as the dangling emotional plotlines are tied off.

This appeals to me, as I like works that contain an extended dénouement – Lord of the Rings is a classic example of this, with several chapters devoted to tying ends up after the final battle and the defeat of Sauron. Terry Pratchett spends quite a bit of time wrapping up his loose ends as well, which I never really noticed until I started listening to Discworld audiobooks, in which you may have 45 minutes to an hour of story left after the climax. I think that most modern novels follow more of a three-act structure, with setup, confrontation (repeated as the tension grows), and then a resolution containing the climax and a small dénouement. Admittedly, I haven’t read many treekiller novels lately, but judging by the number of unfinished Big Fat Fantasy Series out there at the moment, I think we may have to modify the structure to something like introduction -> rising action -> rising action -> rising action -> author’s death.

(I would insert a photo of the shounen-story Plot Shish-kebab [Introduction – Fight – Fight – Fight – Fight – End] in Even a Monkey Can Draw Manga, but I sold it to Half-Price Books during a mad, futile attempt to reclaim shelf space.)

The extended dénouement of the five-act structure is something I haven’t often noted in comics, with one exception that suckered me into reading the X-books for a few years*, probably because with most monthlies, you’ve got to grab readers who pick up books and keep them on the edge of their seats, and never quite finishing a story up may do that. I expect that extended closing sequences may be more the domain of one-shot graphic novels and miniseries, if utilized much.

*(When the X-Men cartoon came out in the early 90s, two (female!) friends of mine sat me down and made me watch it, pausing the tape every time a new character came on and explaining who they were and how they fit in. That intrigued me enough that I picked up that month’s issue of X-Men, which turned out to be a quiet dénouement issue after a huge battle that mostly consisted of characterization and characters musing on life. It grabbed me in a way that big battles never did, and I read a lot of the X-books until I went to grad school and had no more money to buy comics.)

The novel follows this same structure, as it sticks closely to the comics, expanding and deepening the world, the characters, and their motivations instead of rewriting them or adding plotlines. It does spend more time on the events in issues #1-3 than 4 and 5, which together occupy about fifty pages of a 320-page book.

I noticed more visual description in the book than I usually find in the novels I read, and I wonder if that’s due to its comic origins – setting the stage in a highly visual manner as you would draw an establishing panel – or just me seeing it more because I know the comics already?

The social strata of the Sun Village is more pronounced here – I could probably whip up an argument that the Wolfrider/Sun Villager conflict represents primitive communistic equality meeting and tangling with a bourgeois stratified society if I really wanted to, but you shall all be spared that. Being a healer, Leetah is very much an elite in her 40-person-strong village, and used to getting her own way. The primal urge of Recognition really knocks her for a loop in a more complex way than in the comic, and her fear of loss of autonomy is explored in more depth.

One advantage the comic has over the novel is that it starts with a present-day conflict – Redlance tied to a sacrificial stone – then flips to a three-page flashback setting up the world and how the elves got there before slamming you back into the action. The novel, on the other hand, starts with an 18-page deadly dull prologue (it’s labeled “Chapter 1,” but it’s a prologue) that explains how the humans greeted the elves when they arrived on the World of Two Moons in excruciating detail. If I picked up this book without having read the comics and read that first chapter, I’d put it back down – if I were an editor, I’d tell the Pinis to excise that section and start right in on the action and feed it in later, perhaps when Savah is telling the Wolfriders how she and her companions settled Sorrow’s End.

I’ll bring this to a close now and look forward to next month’s column, in which a new quest begins and dreamberry wine is drunk!

I also meant to say something about how the role of women in the Wolfrider society is still equal to the men, except in one important case, which actually makes sense when you think about it: in both the comic and the novel, during the Wolfriders’ raid on the Sun Village, only the men take part, and the woman stay behind. In the novel this is commented on, with Dewshine chafing at the bit to join in the fun, and Clearbrook explaining that as the tribe is so small, the women must stay behind this time, as they are the future of the tribe. Clearbrook believes she will have no more children after Scouter, but she stays behind also in case she is wrong.

Later on with the zwoot hunt, when the danger of tribal extinction isn’t quite as high, the adult elves who wish to participate do so without regard as to their gender: both Rainsong (female) and Woodlock (male) stay behind, while the other Wolfriders hunt.