The roundtable isn’t over for another day or so, but let’s go ahead and talk about endings.

Watching The Wire the first time through, I came away with the belief that it had ended on a suitably even-handed emotional note. The systemic problems in Baltimore were far from fixed, but most of the main characters had personal happy endings. McNulty may have lost his job, but he got a heartfelt speech from Landsman, he’s back to sobriety, and he’s salvaging his relationship with Beadie. Pearlman is a judge and Daniels is a practicing attorney and they’re just so cute together. Lester’s retired and making doll furniture with Shardene. Carver, Kima, and The Bunk are all comporting themselves expertly and ethically in their successful professional lives. The heartbreak of Duquan becoming a junkie is counter-balanced by Bubbles pulling himself out of the same hole — sure, it could be read as “for everyone who’s saved, there’s more heading down the same road,” but it also implies that Duquan might someday come out the other side, just like Bubbles. The tragedy of Randy in the group home is counterbalanced by Namon becoming a success under the care of Mr. and Mrs. Bunny Colvin. And even though Michael is surely doomed to a short life of violence and pain much like Omar’s, for the time being his final scene is as badass as any of Omar’s first scenes, and Omar was always everyone’s favorite character.

The final montage round-up of everyone’s status, bookended by McNulty on the overpass, is wistful but celebratory. The audience is invited to their own sort of detective’s wake, where instead of another round of “Body of an American” we all join in the chorus of “Way Down in the Hole,” the “original” version from the opening of the first season (though the actual original recording is used for the second season) for maximum nostalgic value. It’s a gesture for the people who stuck with the show for the entire run, and as one of those people, I actually appreciate the gesture. While I could criticize it for self-satisfaction or something similar, I think it’s actually one of the nice things about serial television that you can take an audience through so much with a number of characters that a montage of “where are they now?” is more than just informative closure. I like a certain amount of ritual and observance, cheesy or conventional as it may be, and so the ending of The Wire left me feeling satisfied and pleased.

The ending(s) of The Wire are actually much more depressing, and since I’m a little bit stupid, I didn’t key into that until the second go-round with the series. All of the happy endings are, actually, escapes. Every character that we see smiling in the ending montage has gotten the fuck out of the drug war in Baltimore (or, in the case of Herc, decided to profit unethically from it). McNulty, Lester, Daniels, Prezbo, all of them have left the police force to happier lives. Bunk and Kima are minding business as usual in the Homicide unit, working their cases and not fighting to try and tackle the bigger problems. Bubbles has escaped in a literal and immediate way. And Pearlman may still technically be in the system, but as a judge, she sits apart from the fray. Every single one of the beloved characters we’ve followed since the beginning have abandoned the mission, because that’s the only way they can achieve fulfilling, happy lives as people.

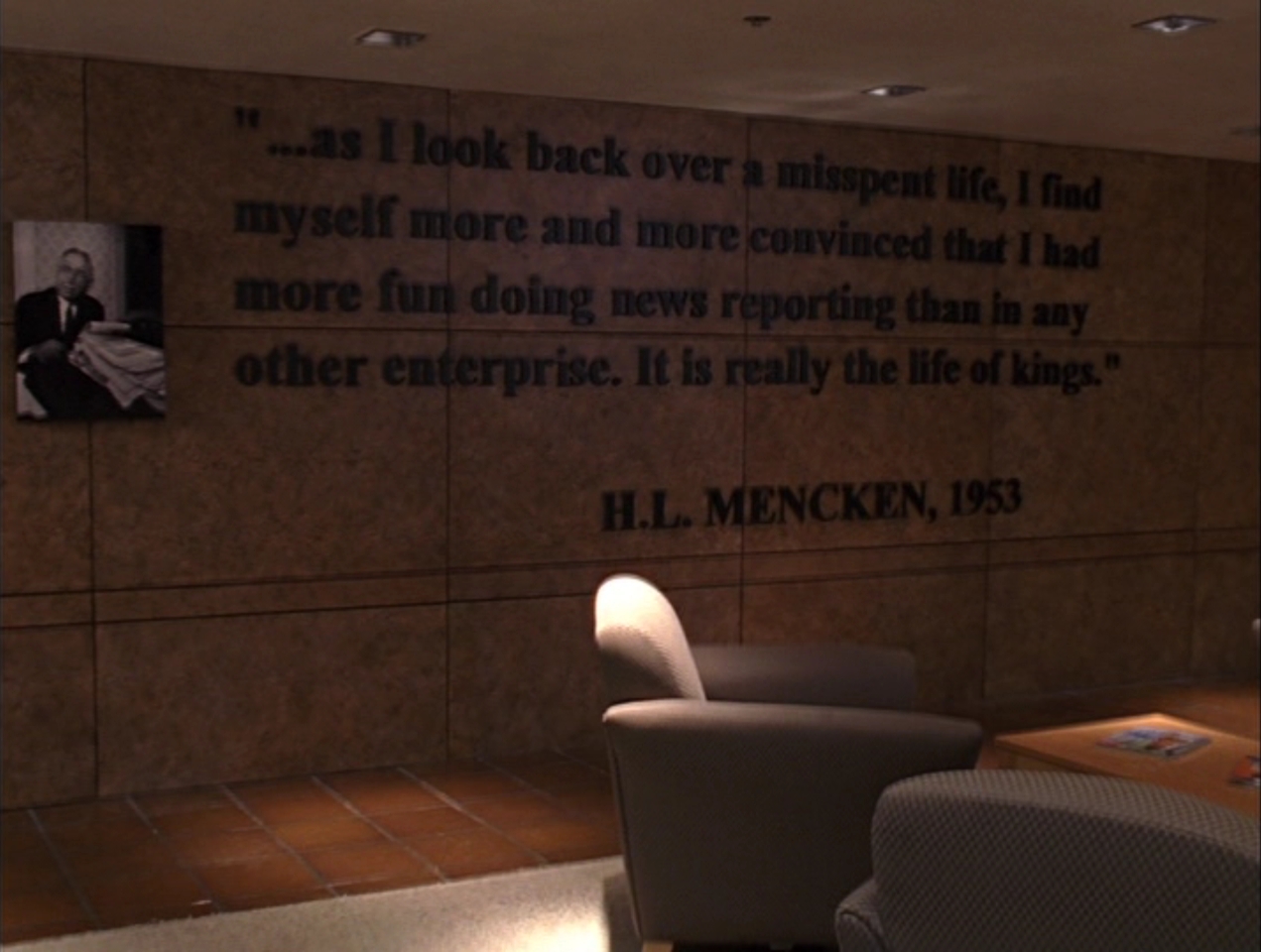

The importance of this is compounded by the fact that David Simon did the same thing. “I got out of journalism because some sons of bitches bought my newspaper and it stopped being fun.” That’s a quote from Simon that tends to make the rounds (I found it on Wikipedia, but it’s orginally from an interview in the Baltimore City Paper). Simon was once a part of the system, working as a reporter for The Baltimore Sun, someone in a position to strive and fail to change things just like all the characters on The Wire. Simon got his own happy ending, though: he escaped reporting to become a book author and TV creator. In a way, the entirety of The Wire is David Simon reveling in his escape, and showing us what he escaped from. Not the streets, or the day-to-day of the drug trade, but the system as a whole. He’s now outside of it, looking back in. And while The Wire may be a multi-faceted, complex show full of characters and viewpoints that contradict one another, the end of the show and the life of its creator point to a single, unmistakable message: You better get while the getting’s good.

I’m not sure if it’s a compliment or criticism of the show, but I can’t think of a more depressing or terrifyingly bleak moral than that. It might be the truest sentiment ever expressed on television — but I don’t like to think about that any more than I absolutely have to. I’d much rather escape.

_________________

Update by Noah: The entire Wire roundtable is here.

This almost makes me like the ending of the wire. Not sure it quite manages it…it’s not clear to me that they quite saw the bleakness you do, and just in general montages give me pains….but it’s close.

Well, like Simon’s escape, or McNulty’s escape–if we want to call it that–or Bubbles’s escape, the end of The Wire isn’t something I think of in terms of “liking” or “disliking.” Plot lines aren’t neatly concluded. I don’t love montages, either, but they seem somewhat necessary at times in this series.

I agree with Jason that it is sort of a disturbing ending. You either “get out” having had a fucked up life, or you may have died if you were part of the drug game, or you’re sort of left suspended where you were, like Kima, Bunk–even Mrs. Sobotka and other characters we didn’t get to know well.

Well, this comment is kind of all over the place. Appreciate the conversation, anyway.

Good summary of the final moments.

The “appearance” of closure & personal happy endings did involve most everyone either abandoning the “institutions” of police or drug dealing/selling – walking away from a war that can’t be won, and won’t end.

Though they didn’t make it into the montage I’m thinking too of Bodie in the shoe shop; he escaped from the corner, got out of the Barksdale/ Marlo institutions. But poor old Nick Sobotka, last spotted demonstrating at the port development and getting arrested, still fighting the institution, still losing, still suffering.

Those who remained “inside” at the end Pearlman & Daniels, Greggs & Moreland, had me feeling like the story was rewinding – The Wire started with a pissed off Homicide Cop deciding to prod a judge into action. Would these guys, so burnt, ever try again? Or would they just try and survive the institution?

Simon has said The Wire is based on Greek tragedy – where once individuals were subject to the whims of the Gods, in The Wire the are at the mercy of institutions. To escape from these institutions is, then the only action that makes sense.

I spent 13 years as a cop (not in Baltimore but in Sydney, Australia) and I walked away burnt out, depressed and despairing. I explain it this way: I got tired of constantly meeting people for the first time on the worst day of their lives.

From where I sat, I couldn’t help but cheer the decisions to walk away.

I’ve only just discovered the site – congratulations, it’s truly fabulous, and, er, um, sorry ’bout crashing it by retweeting your Dickensian Wire earlier today.

Hey Pam! Nice to see you here as well as on twitter. And don’t apologize! Everyone linked it — and we were happy to have the traffic!

Stupid pedantic correction: it’s Poot in the shoe shop. Bodie gets murdered.

Well if David “escaped”, he escaped from the jailhouse to the super-max…straight into another dozen years of telling those same tough Baltimore stories that weren’t being told, this time in a more complex and rich format that would reach a whole new audience. Then, when the Wire had reached it’s pinnacle, he “escaped” to tell the stories of a city that was literally washed away by government greed, incompetence and neglect and then abandoned by the richest, most powerful country in the world. New Orleans was the home of the first daily black newspaper and one of the first cities to allow black people to own homes. The depth of historic, intact, generational cultural traditions and complexity of racial conflict and peaceful multiculturalism intermingling in this city is a block by block phenomena that makes the geometry of Baltimore’s subtle cultural exchanges seem like basic arithmetic by comparison. I don’t love David’s bulldog interviews and they certainly open him up to the critique of being a reactionary over-simplifier. That said, the most surface viewing of his work puts the lie to the idea that he approaches anything in a manor that is less than three dimensional. And people who think telling the defiant and often tragic stories of New Orlineans is an “escape” have never set a foot off of Bourbon street.

He’s famous; he’s rich; he doesn’t have to screw with the institutions he despises (or at least can do so from a position of power.) I think that’s an escape.

So we only like it when people go after unfair power structures and bureacratic institutions from a position of powerlessness?

Cool, I get it. Shake that Fist!

Still, I don’t see this David, as escaping.

http://weblogs.baltimoresun.com/news/crime/blog/2011/01/simon_responds_to_bealefelds_c.html

Thanks Noah – and d’oh, of course! Poor Bodie never did make it off the corner.

Poot and Bodie, both there with sad, scared little Wallace at the end, and back then, if you’d had to pick who was going to be the “harder” man, it would’ve been Poot.

Jenny, what are you talking about? Neither Jason nor I said that Simon was wrong for escaping, I don’t think. And obviously fighting the power is a lot easier if you have power yourself. But Simon’s still escaped, and that particular escape is not easily generalizable; most people (even most reporters) aren’t going to become star TV creators. If that’s the only option out, it’s not a very happy ending for most people in Baltimore or the country.

Jenny,

I’m not criticizing Simon for escaping. In many ways I’m glad he did — I got some amazing television out of it. But “The Wire”, as good and as truthful as it is, is still not journalism. He’s not dealing with the day-to-day of the death of his city, he’s writing about it as fiction from a distance. Which is a totally noble thing to do, but is also a form of escape, in that instead of actually living the hell he depicts, he’s rich and famous and making a television show about the hell he escaped, which resonates with all the happy endings on the show involving people turning away from the central conflict of the show and giving up on it. Do you see what I’m saying?

One of the things that’s particularly hitting me about this “escape” question is how much it drives home the power of television and the impotence of contemporary journalism: if Simon had stayed in Baltimore, writing for the increasingly corporate and co-opted Sun, would he actually have been able to do any more for urban inner city issues than he did via the Wire?

I guess I’m skeptical that anybody inside of that situation can actually ever do anything to affect it, because the power disparity is so structural and so obscuring. As much as I like the romance of the idea that people in a situation are the best people to transform a situation, in this case escape might actually be a pre-requisite for action.

Jenny’s link is interesting with regards to that: the Commissioner saying that the show is a smear on Baltimore. I don’t get that — it sounds like something the head of tourism for the city would say. Does he want Baltimore’s crime problems swept under the rug so nobody but the police know they’re happening? Is that really an attitude that’s likely to build the political will to make the situation better?

I am talking about the meaning of the word escape.

Calling what Simon did “escape” implies that the fight is only happening in one dimension. The newspaper reporter is no longer fighting at the newspaper level but he has moved the fight to a different place, to the crime drama Homicide, where he showed a bit of real life in a sort of generic show. From there he used his “power” and moved the fight to a place where he could increase the depth and complexity of the stories he told, (Wire). From there he moved the fight to another even more fkd up, and more complex city which further universalizes the challenge from one “broken city’s problem” to systemic failure across borders.

Your argument that in the narrative of the final episode only the people who walk away from the systemic fights survive and thrive is one I need to look at more closely and that would take watching that episode again which I haven’t done in years. You might be right. If it wraps up that uniformly, (happy people walk away/escape from the fight and others are ground up within it)that could be that David is justifying his own escape through his characters just as you say.

Personally i don’t think he is escaping and I don’t think he thinks he is escaping and I think he probably doesn’t think that his characters are escaping but we can differ about that and that’s what I’m talking about.

I’m also asking a more complex question. If the characters can only have incremental wins (and losses) in their day to day fights in a corrupt and entrenched system. Then maybe the real fight isn’t in the incremental fights (or it isn’t only there)? Maybe the more important fight is fighting at a higher level. If they were to keep up with the Sisyphean task of working the corners or arresting the corners in some ways they would simply be “escaping” the higher purpose of true change.

This also speaks to the challenge of focusing on only a handful of characters and sticking with them. We either believe that there is only one McNulty (to take one example) and once he’s gone no one will ever go to the extreme lengths he went to in fking with the machine. Or we can believe that he is an archtype and that there are other McNulties in the system that were not the subject of the story and that the Wire is telling a larger story about individuals struggling with power and institutions through a handful of individuals, in one city over one series of years.

I think that the overwhelming feeling that I got from the last episode is that the people change, and transform, (some good, some bad) but the system remains. I think it’s less a story about how nothing people do works, so the only option is escape, and more a story about how big the problem is and how big the solution is going to have to be. IMHO

If Simon wanted to walk away he’d be doing something very different to what he is doing.

“If the characters can only have incremental wins (and losses) in their day to day fights in a corrupt and entrenched system. Then maybe the real fight isn’t in the incremental fights (or it isn’t only there)? Maybe the more important fight is fighting at a higher level.”

That’s what Carcetti says. I don’t think we necessarily are supposed to trust him, though.

“Maybe the more important fight is fighting at a higher level.”

I think the disagreement is on whether or not getting oneself to that higher level is a form of escape. Once you’re at the “higher level” (arguable term — I would say “separate space” or something similarly neutral in judgment) of TV Dramatist, you no longer have to worry about institutional retribution or dysfunction affecting you personally or your work. Simon no longer worries about a Baltimore Sun editor spiking a piece of journalism because it’s too complex and not Pulitzer bait. He may need to negotiate with HBO Execs, but that’s a completely different system, which is my point — he is now separate from what he is looking back and commenting on.

I’m a huge fan of The Wire and I’m coming aboard the chat for the first time… Great give and take here… If I might ask–Any chance we’re talking about three different things? First, we seem to be talking about aesthetics. Was the ending of The Wire aesthetically rich/successful/moving…whatever word you want to apply. Second, we’re also talking about morality. Is making art as moral/important/noble/enlightened as trying to improve the system while living within it? Finally, we’re blending two other questions. On one hand, we’re asking if The Wire is journalism. On the other hand, we’re asking if The Wire is as noble or philanthropic as the best journalism can be. All seem to be entirely separate subjects, I think, that happen to overlap because this show is so brilliantly complex.

As for the first subject, I think the ending is even-up. Which makes it pretty good. Poems can end well; movies are novels rarely do—even the best good ones. (Two exceptions: Casablanca and the Great Gatsby.) This ending is more like Stephen Crane naturalism, not Mark Twain realism. Everyone is caught in the grip of fate and genetics. Baltimore goes on, not worse or better. Some get out, some don’t. Some will live improved lives, some won’t. We get to like the fact that some of the characters, including my personal favorite Lester, find some kind of happiness. But, as Willa Cather said, the journey is all, the goal (substitute “ending”) is nothing. Ultimately, we have to accept the diminuendo of the last montage (with the original version of the song) as a kind of a downer swoon, something like the endings of Casablanca and The Great Gatsby. We will never get a chance to be carried away for the first time by this particular art piece again.

The second question about art and morality is impossible to settle, of course. Eye of the beholder and all that. For me, I think we good citizens do service in the local community as much as possible, while also taking care of our deepest aspirations. If you’re an artist, the aspiration is clear. You make the art. If you’re lucky, the art may help to improve the world. I can tell you that The Wire improved mine, though I make a good wage in America, which is to say, I’m privileged.

Which brings me to the blurred questions involving art and journalism. The first issue here seems clear to me: The Wire is not journalism?though to a small degree, like a rare and powerful piece of journalism, it may have had some social impact on the way a few people in power see the inner city, the drug trade, policing, journalism itself, education, etc. Still, it’s primary function is as art. I take this to mean that it is intended as an expression of the imagination, a work meant to entertain on a visceral and ideational level.

Finally: Is The Wire as high a calling as something equivalent in journalism? I believe both are “high” callings. Oddly, in the U.S. it’s possible to make “good” money while not selling out your soul in some boring business career you regret. Just because you’re making a TV show doesn’t mean you’ll get rich doing it. If in the beginning of your career you aspire to journalism or art, you MAY get rich, but you understand that the odds are you won’t.

The Wire has been watched by a relatively small percentage of viewers. Still, the writers and directors and producers are doing very well, I’m sure… Does The Wire have as great an effect as journalism? There again, hard to say. Let’s assume this: The more people who encounter a powerful journalistic or artistic statement, the greater the odds of social improvement. If we go by the numbers, we know that most moviegoers prefer the fictive over documentaries. Then again, most readers prefer non-fiction to fiction. Some movies cause a shift in national or community conscious, but most, even the very best, do not. Most Pulitzer Prize winning articles or documentaries are the same. Over a lifetime, a journalist may be able to compel change here and there. Over its lifetime as a film, the same can be said for The Wire. Seems to me a draw.

Pingback: links for 2011-04-26 « Embololalia