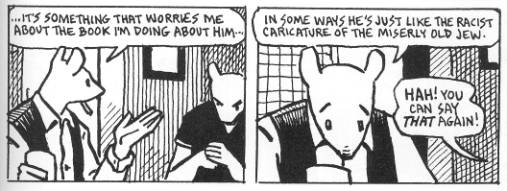

I’ve been tussling with a blog full of academics over at the Comics Grid (they even quoted my brother at me!) on the subject of Maus and metafictional conceits. Ernesto Priego in the post argued that Maus smartly employs self-reflexivity and irony, particularly in its use of comic-book tropes like caricature.

Priego:

In the panels above, Artie expresses the melancholia caused by the double bind in which he is trapped by trying to deal with his father’s story (and, as we know, with his own story with his father) through comics. The ironic effect provoked by the juxtaposition of the word “caricature” in a dialogue uttered by a cartoon character unavoidably indicates an illuminating self-reflexivity.

By blurring (and deliberately confusing) the distinction between empirical author and fictional persona, Spiegelman appears conscious that every representational practice implies a distortion (“caricature” is indeed understood as the graphic distortion of recognisable features, usually to achieve a humorous, ironic or parodic effect) and that this is problematic when one is attempting a narrative which makes “truth claims” (Ricoeur 1988:188-192), like the testimony of a Holocaust survivor.

So caricature emphasizes the inevitable distortion of representation; thus comics is especially suited to exploring the problematic nature of truth claims.

I think this pretty much gets things completely backwards. To see why, here’s a poem by Paul Celan (translated by Michael Hamburger.)

It is no longer

this

heaviness lowered at times together with you

into the hour. It is

another.It is the weight holding back the void

that would

accompany you.

Like you, it has no name. Perhaps

you two are one and the same. Perhaps

one day you also will call

me so.

As with Celan’s poetry in general, this is mysterious — or, to put it another way, fucking confusing. There is a heaviness…then there is another heaviness….there is a you without a name. Which hour? Which weight? Who is me? The “heaviness” and “lowered into” suggest a coffin or death, but only elliptically. And there are two deaths? Or perhaps a dead person and his (or her?) death? The weight of the void, the void in the weight, press on each other, and something escapes. The poem ends up as an elegy for its own meaning. The heaviness is gone; a void slips in. The “me” at the end is not a self so much as a wavering echo of self; the shadow of an ego that hopes to be called, perhaps, by a friend, a voice, that cannot even be named, much less remembered.

Celan’s work is often seen as a long struggle with the problem of meaning and representation following the Holocaust…which is also the problem of meaning and representation in the face of death. Language in his poems doesn’t so much crack as scuttle to the side. The heaviness of speech is not the heaviness of reality; one can call the other, perhaps, but not be it, and that distance is a pain that can itself barely be expressed. Celan is always on the verge of fading into silence; his poems careful scrawls surrounding their own inevitable dissolution.

The tension in Celan’s writing, then, is precisely because of the inadequacy of his resources. Language can only guess at identities (“Perhaps you two are one and the same,”) but language is all he has.

Spiegelman claims a similar kind of tension, a similar difficulty of representation. But his art does not justify the claim. On the contrary, the use of caricature, which Priego sees as emphasizing the problems of communication, actually finesses it.

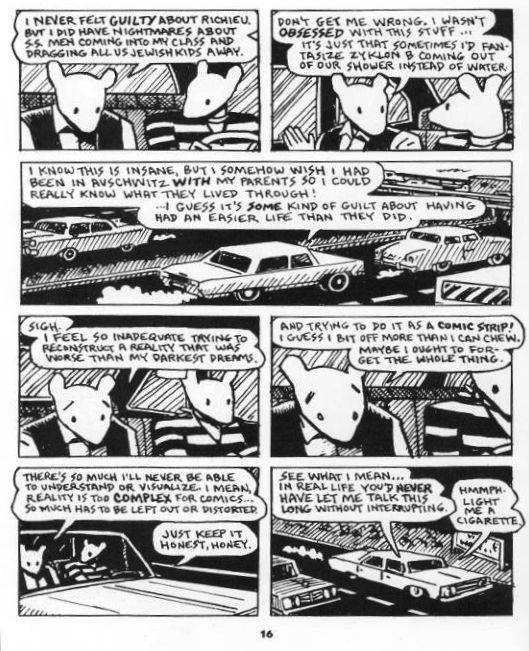

The characters here talk about the inadequacy of comics representation. Caricature — the way Vladek is portrayed and, of course, the fact that the characters are drawn as mice — is discussed as false. But that falseness is represented unproblematically through language. You can see this even more clearly in another page Priego reproduces:

The last panel comments on the fact that this is a comic strip; what you see is not reality. But the very fact that what you see is not what you get actually underlines the truth of the final panel, where Artie says, basically, “this is not reality.” That statement, the accuracy of that representation, is not questioned. Language in Maus can, and often does, tell the truth, a fact continually emphasized by the fact that images do not.

In short, caricature is an easy out. Spiegelman’s mice offer a comfortable answer to the question of “what is real.” That answer is, not the surface, but the essence; not the caricature, but the language telling you it is not the caricature. Spiegelman questions whether he is telling the story right, but that’s a methodological, not an ontological question. Indeed, the methodological questions allow him to avoid the ontological ones. Spiegelman questions cartooning in order to avoid more difficult questions. Which is why, despite all its vaunted self-reflexivity, Maus is consistently and cripplingly glib.

I have no comments on Maus (I think like superhero comics, I’m calling a moratorium on my participation in anything involving them), but I love that Celan poem. Thanks for sharing it.

It’s such a fantastic translation too. I think my favorite part:

“Like you, it has no name. Perhaps

you two are one and the same. Perhaps”

is kind of great because of the name/same rhyme, which isn’t in the original as far as I can tell.

The Celan poem is, as far as this reader is concerned, a red herring. “What’s he to Hecuba?” What’s Celan to Spiegelman? Nothing.

There’s an additional layer of irony in play because Noah has quoted a translation: so it’s OK to transpose Celan into another language, but not OK for Spiegelman to do the same visually with his father.

The ‘caricature’ referred to in the text has nothing to do with the visual depiction of Vladek, but rather with Spiegelman’s presentation of Vladek’s modern-day actions.

Spiegelman’s “mousing” of his dad is, in fact, anti-caricatural– rendering generic what caricature emphasises: individuality. Caricature is about revealing: this “mousing” is about masking.

The “meta” in Maus is coolly, and (I would say) courageously assumed; there aren’t many artists who would so willingly invite the reader to doubt his approach. Spiegelman is the Brecht of comics, inviting a cerebral, detached judgment of an intensely emotional story.

Celan’s a writer who is fascinated by questions of representation and the Holocaust. If you can’t see why that relates to Spiegelman, I can’t help you.

Translating always loses something, obviously. It’s a necessity to allow a broader audience. As I said, I think Hamburger’s translation is bautiful. Spiegelman’s transposition of his father is just dumb. It’s not hypocritical to say one person did something well and another did something poorly, unless you resent the whole idea of comparison…which of course comics fans often do.

Every single fucking post modern writer is willing to invite the reader to doubt his approach. Celan does it, for one. Borges, Nabokov, Barth, and on and on. It’s de rigeur. There’s nothing either original or courageous about it. Suggesting it’s original and courageous, as Spiegelman does, is, I would argue, tiresome and ridiculous. But that’s me.

Finally, Spiegelman specifically links his portrait of his father to caricature, which has to be seen as about visual depiction in the context of a comic.

How would YOU know that Hamburger’s translation is beautiful?

Parlez-vous français, Noah?

For all you know, the translation is a travesty. Original, please.

“Finally, Spiegelman specifically links his portrait of his father to caricature, which has to be seen as about visual depiction in the context of a comic.”

Except– as I pointed out, this being obvious– it isn’t. It is the exact opposite.

“Every single fucking post modern writer is willing to invite the reader to doubt his approach. Celan does it, for one. Borges, Nabokov, Barth, and on and on.”

Pretty terrific company to be grouped with, Noah.

Yes. But Spiegelman doesn’t look very great compared to them, unfortunately.

It’s not the exact opposite. Spiegelman uses the caricatures to show that the comic isn’t true. He also refers to himself as caricaturing Vladek, which he says isn’t true. But he doesn’t question the words he uses to tell us it isn’t true.

Seeing caricature as about individuality flies in the face of hundreds of years of caricature, which tend to emphasize racial stereotypes. They emphasize generic qualities, masking individuality. Thus, Spiegelman’s masking of his father works quite well with traditional anti-semitic depictions, which also emphasize genericness and downplay individuality. Spiegelman is quite correct to link the history of caricature to the history of anti-semitic potrayals. His mistake (from my perspective) is to suggest that by pointing out the caricature/mask he is revealing the real. Celan’s is a much fiercer and much more uncompromising take on the tragedy of language and of the real.

Noah, ach, this is more of your tendentious, hammer-blunt, idol-toppling perversity at work.

Your method, from my POV, is to work by comparison/contrast to things you esteem, find fault on the basis of those personal points of reference (as in, Spiegelman isn’t Celan), then point out that, besides the much-idolized comic in question, lots of other artists, in other media, other forms, have engaged in the same things — in this case, self-reflexive and metanarrative feints — so that these are, ho hum, hardly new (even though Spiegelman’s way of doing them was decidedly new to comics). Then you elevate the comic’s use of such common devices to a moral failing, as in, Spiegelman is glib. Then, when confronted, you persist in dissing the comic in question as, here you go again, “tiresome,” old hat, and inferior to works in wholly other forms, works whose agendas and burdens and formal affordances are light years away from the comic in question.

FWIW, you’re entirely wrong about Maus being merely glib. This was the tack I took as a reader initially, back in the mid-80s, due to my own initial resistance to work that exploded or ignored the boundaries of comic book culture as I, an ardent fan, understood it. But when I finally read, years later, the completed Maus, I realized that this was a moving, indeed for me deeply affecting, work that used intellectualized conceits and circuitous method to earn, and make the reader earn, a stunning emotional effect. Maus moves many people for a reason, something your dismissive posturing cannot account for.

In hindsight, there’s nothing glib about Maus at all, and you’re condemning it (condemning is not too strong a word) precisely for its use of the comical, its word/image tensions, its aesthetic effects. You’re condemning it for not rising to the ontological heights, or depths, of Celan, for being something other than what your straw argument insists that it must be. You’re faulting its medium-specific complexities as simplicities. In essence, you’re adding your voice to the chorus of shallow ad hominem criticisms based on a dislike of Spiegelman’s persona, the kind of obtuse, tone-deaf criticism seen in, for example, Harvey’s willful misreading of the book in his The Art of the Comic Book.

Spiegelman will always be subject to arguments that he is “glib.” His refusal to tack away from the comical, his refusal to deliver what others expect of a Holocaust account, and his deeply fraught portrayal of his father are bound to rub a few readers raw. But the charge is itself glib, unearned.

Note that Spiegelman never affirms that his portrayal is “real” in any straightforward, uncomplicated sense. Not even his words do this. Attention to the text, the whole text, verbal and visual, reveals that, as Vol. 2 speeds to its end, Maus unpacks layer after layer of hopeful artifice, and ends on a deliberately deceptive note, whereby father and son together fantastically reconstruct the absent mother who, we know full well from earlier chapters, cannot be restored, indeed is the irrevocable and constitutive absence, or loss, around which the book is built. You haven’t even begun to plumb the depths of this layering.

Again, from my POV your considerable writerly gifts are being sabotaged by your crushingly obvious yen for idol-toppling. The way you swing that truncheon of ideological criticism, in predictable and predictably unsympathetic ways, is a stone cold drag. You’d give us much more if you stopped trying to enrage fans and instead applied your needle-sharp intelligence to actually reading the comics with due attention, without trying to make the alleged limitations of the comics into a warrant for swinging that stick.

Hey Charles! Figured you’d show up!

First, I’m not trying to enrage anyone. Comics fans are just really easy to enrage. That’s not my fault.

I kind of think your comment deconstructs itself nicely here:

“even though Spiegelman’s way of doing them was decidedly new to comics”

Indeed. Why should this be at all a point in his favor exactly?

And many things aren’t really worth that much attention, you know? I read a bit of John Grisham recently. Do I need to read the entire work to determine that it sucks? Maus is better than John Grisham, I’ll admit. But not so much better that I need to reread it infinitely to determine that it’s mediocre.

Also…you seem upset that I should compare comics I don’t admire to work I do. See what I said earlier about comics fans really quite embarrassing discomfort with comparisons.

Oh, and since we’re taking out the knives…your reiterated defensiveness around the low status of “comicalness” and your equally defensive claims of expertise do you, your writing, and comics no favors. I understand that it’s important to raise comics status and usher them into the shining halls of academe. But turning your loves into idols is no particular kindness, and codifying disciplinary boundaries is a way not to protect the work, but to consign it to irrelevance. Comparing Spiegelman to Celan, even to condemn him, is much more respectful than your really ridiculous plea that what he’s doing is worthwhile because it’s new to comics.

Though…as always, I appreciate you coming by, and find your different approach stimulating as well as maddening.

Wait till Eddie Campbell next week, though…

That ends on an ominous note. I take it me and Charles (or me, at least) are going to be whaling the crap out of you about Campbell?

Funny somebody was quoting me at you, Noah. In my revised reading of mouse, I actually kind of disagree with my 2003 self–but I’m not agreeing with you either (no shock there, I guess). To me, the notion that Spiegelman’s use of animal faces and masks is obvious and hamfisted is just wrong. This was a clever way of exploring the tension between notions of biological race and social construction and how those play out in both Nazi Germany and contemporary Catskills (and environs)…The use of animal masks then complicates the already clever animal metaphors. It is a deceptively simple ploy, but one that plays big dividends. The comparison to Sterne, Nabokov, Borges, etc. isn’t always flattering to Spiegelman, admittedly, but he does, in some ways, have bigger fish to fry than they usually. Nabokov and Borges make the formal play the central point of their narratives quite often–while Spiegelman wants to (and probably psychologically needs to) take on one of the biggest historical tragedies of the twentieth century (no, I’m not going to make a ranked list–but it’s a biggie). Nabokov’s playful revealing that Kinbote’s Zembla AND his own novel are not “real” doesn’t have the same potential disturbing relevance of suggesting that eyewitness holocaust testimony is “not real.” Likewise, Borges’ personal presence in something like “Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis, Tertius”–and its collision of “real” and fictional worlds–is only philosophically invested in the questionable “reality” of our world–it does not explore the social and political ramifications of revealing “historical” reality to be construction. There are other books that are more similar to Maus in this regard (“historiographic metafiction” is a genre of its own), but Sterne, Nabokov, and Borges, while flattering, may not be the best comparisons. I agree with some of the above (and Charles’ book) that the metafictiveness of Maus is somewhat paradoxical–working to simultaneously disavow the reality of the narrative–and to lay claim to historical reality–but this kind of playfulness seems less “playful” and lighthearted (as in Sterne–one of my all-time favorite books btw). It does work for different purposes, however, without undermining Vladek’s narrative. Spiegelman’s a very cerebral and clever creator (as the Breakdowns stuff makes abundantly clear)– and applying that kind of mentality to his father’s Holocaust narrative combines strong emotional experience with interrogation of that experience. Maus is, in the end, a pretty great book, although I have never really embraced it fully myself, being raised on Holocaust guilt in Hebrew school–and never having really wanted to go back there. I try not to let my ethnic self-hatred completely dictate my response to the book, however.

Hey Eric!

I think your 2011 self is more convincing than your 2003 self also. However!

First, I think you’re somewhat underestimating some of the political and moral elements in Borges and especially in Nabokov. They’re not as obvious (some might say leaden) about is as Spiegelman, but…Tlon is arguably about totalitarianism, and Lolita is definitively about child abuse. Not to get too Domingos on you, but serious artists do tend to engage with serious issues. Spiegelman’s really, really ostentatious about it, but I don’t think that actually means that he’s more serious or more insightful. Quite the reverse, in fact.

Second…the main comparison is to Celan, who is as enmeshed in the Holocaust and its aftermath as Spiegelman is. The difference is that Celan’s take on the ontological issues is really subtle and weird and haunting, whereas Spiegelman’s comes down to little more than the hopelessly cliched “dare we talk about the Holocaust?!” (Charles seems ready to dismiss Celan…which I’d actually be pretty interested to see. I presume it’s on the grounds of being too confusing or inaccessible?)

I guess I’ve kind of hit the third point, which is just that, despite reading you and Charles, I don’t find Spiegelman’s questioning of reality in any way insightful or provocative. The beginning of the second part, where he’s got the mask on sitting atop the pile of corpses complaining about his success…I just found that unendurably pompous, clumsy, and obvious. I mean, like, throw the book across the room unendurable. And all the little details in that vein — “just keep it honest, honey” — I mean, fuck off. I have no desire to see you patting yourself on the back, and/or chastising yourself in the same tones of reverential self-revelation as every other half-assed confessional nitwit who’s ever come down the pike.

I didn’t hate all of Maus. Like I said, there’s an interesting story there, and Spiegelman tells it well enough. I wish the art were better, but it could be worse too. But the metafictional stuff is just really not very clever, to put it kindly.

Rober — yes, you and Charles and everyone else are going to beat me bloody. Even Suat likes that book! I am doomed.

Huh? I like the book (i.e. The Years Have Pants)? There are parts I like and there are parts I like less. Maybe Caro will be on your side…

I definitely don’t think Maus is a great work of art though.

Oh, that’s comforting. I thought you were more enthusiastic.

Caro’s at least fairly positive, from what she’s said.

What are your reservations about Maus?

I agree that Borges’ work, in general, has some interesting things to say about authoritarianism…and especially about the disturbing human need for “order” and for things to “make sense”–Tlon fits into that pattern, admittedly—but, as with much of his work, somewhat obtusely–He was unlikely to take flack from the broad(er) public for his somewhat ambivalent attitudes towards these things in his fiction. Likewise, Lolita, obviously, has something to say about pedophilia–although Lolita wasn’t the example I was using for selfish reasons (i.e., I haven’t read it in awhile and am not prepared to launch a lengthy argument about it). Still, while Nabokov does address social and political realities, particularly in his Russian novels, which I’ve been working my way through of late–his reputation as a master of formal tricks at the expense of “serious” content, is not totally unearned. I’m not trying to say Spiegelman is better than Borges or Nabokov, though, as they’re both favorites of mine (and I tend to be a sucker for formal tricks myself)–All I was saying is that using self-reflexivity in the context Spiegeman does leads to different effects—and that the comparison is therefore flawed. I can’t speak to the Celan, really—as I haven’t read much Celan–and I didn’t even read this article of yours! Having seen your spiel on Spiegelman before—a few lines allowed me to comment freely. Just hewing to Berlatsky family logic.

“and I didn’t even read this article of yours!”

Hah! Well, it’s true we’ve had this conversation before! You should read the Celan poem though; it’s pretty great.

Yes, I am positive about Alec. I’m still working out exactly what I’m going to say, though.

What the literary critic in me likes least about Maus is that it is so reliant on symbolism that the symbols remain inescapably, insistently symbolic throughout. They never stop being marked by their symbolism, so the non-symbolic significance never quite “lives” for me.

This is exacerbated by the fact that there’s not much contrast between the story-without-the-symbol and the story-with-the-symbol. The predator:prey::Nazis:Jews analogy is so simple, so straightforward itself, that once it’s established you can’t really step away from it and experience the story without it, so you can’t get that nice doubling effect that you get in narratives where the conceit is more subtle and less integral to the narrative.

That doubling effect is like shining a pointer on an aspect of the concept that you never would have noticed (so that you suddenly see two things where before you saw one, like those visual games — is it faces or a vase?). The symbolism in Maus doesn’t do that — you always saw the Nazis and the Jews in this predator/prey relationship; so Maus just makes palpable and emphatic something that you knew anyway. It’s an effective symbol for genocide, one that really drives home the point, but it’s not a surprising one. Making it so tangible through the imagery is an achievement, but it’s not the imaginative and uncanny sort of achievement that makes writers like Nabokov and Borges so satisfying.

I can get past all that though and recognize a successful symbol of that ilk, although my preference is for the trickier stuff. But I actually just find Spiegelman’s prose absolutely, utterly intolerable. Even reading the excerpts above makes me shudder.

@Noah. “Also…you seem upset that I should compare comics I don’t admire to work I do. See what I said earlier about comics fans really quite embarrassing discomfort with comparisons.”

Noah, the problem with your comparative approach (and I’d also add the similiar comparative approach that Ng Suat Tong often uses) is not that it’s unfavorable but that it’s ahistorical and inattentive to formal questions. If you had said Spiegelman was better than Celan, Borges and Nabokov, your comments would be equally obtuse. There were a lot of old line fans who would compare Caniff with Rembrandt and Hal Foster with Michelangelo. I found their criticism as callow and unhelp as yours is, for the same reason even though they celebrated Caniff and Foster. These kinds of comparisons across forms and across historical eras and cultural barriers need to be done with a great deal more intelligence and care than you’re willing to apply, with a due acknowledgement of the differences at work. (An example of someone who does it well is Will Pritchard who has an interesting comparison of Boswell with Crumb — but this works because Pritchard is careful to situate both Boswell and Crumb in their artistic and historical contexts. See here for an earlier post calling attention to Pritchard’s work: http://comicscomicsmag.com/2010/06/doing-justice-to-crumb.html)

Because you’re impulse to sneer is stronger than your impulse to read or analyze, these posts always sound like childish taunting rather than criticism: The child’s argument that “My dad is stronger than your dad” is transformed into “My Celan is stronger than your Spiegelman.” These are among the most unhelpful bits of criticism I’ve ever read.

The original poem:

Es Ist Nicht Meher

diese

zuweilen mit dir

in die Stunde gesenkte

Schwere. Es ist

eine andre

Es ist das Gewicht, das die Leere zurückhält,

die mit-

ginge mit dir.

Es hat, wie du, keinen Namen. Vielleicht

seid ihr dasselbe. Vielleicht

nennst auch du mich einst

so.

Paul Celan was a great poet, a great artist. From the top of my head I can only think of one truly great comics artist in the restrict field. His name isn’t Art Spiegelman.

Comics fans have very good reasons to be essentialists. The art form almost never attracted great artists. Not even in a parachute, falling off route, did they fall in the comics field.

…I mean Yoshiharu Tsuge above, of course…

Ah, well, Jeet; I often (though not always!) find your writing quite unhelpful as well. Different strokes, and all that.

I mean, to me, Jeet, you often seem absolutely paralyzed by your own pedantry. You’re so determined to be careful, and often so determined to be reverent, that you won’t actually say what you think. You say it’s important to make “due acknowledgment of the differences at work,” but important for what? So that you can carefully slot everyone into their exact place of worth, doling out praise and blame in exactly proportioned measures? Who does that benefit? Are you engaged with the living world of art or are you compiling the Key to All Mythologies?

Celan and Spiegelman are both dealing with issues of representation in relation to the Holocaust. I think Celan does a better job. I said so. I explained why. You disagree? Disagree. But don’t tell me that I’ve violated some tenet of scholarship or criticism because I’m unwilling to qualify my opinions with hemming and hawing and pleas for other critics to go say something substantive because I can’t be bothered now.

And as for sneering — sneering is fun! You and Charles think so as well; you’re just more comfortable sneering at fellow critics than at artists. I’m not interested in making that distinction…but as I said before, different strokes.

Caro, that’s pretty much where I’m coming from as well. I just didn’t feel that Spiegelman, when he goes metafictional, ever teaches me anything, or tells me anything I didn’t know, or gives me the little oooh! of awe or wonder that I want from my art. It’s just really flat.

I think Charles (and perhaps Matthias) would say that we’re ignoring the comic qualities, the tension between picture and word. I don’t buy it, but I think it’s the counter-argument.

On the other hand, I think I actually may like his prose more than you do…at least the Vladek narration part. I read all the way through Maus without much trouble because of that. I don’t know that I exactly enjoyed it, but I did finish it (it’s like Y the Last Man in that way for me.)

@Caro:

What the literary critic in me likes least about Maus is that it is so reliant on symbolism that the symbols remain inescapably, insistently symbolic throughout. They never stop being marked by their symbolism, so the non-symbolic significance never quite “lives” for me.

But the grounding and function of the symbol keep changing; that’s the thing about Maus. Spiegelman keeps working on, fussing with, questioning, challenging, the foundation of the house even as he lives and works in it. His relationship, and therefore the reader’s, with the symbol keeps modulating, particularly in Vol. 2, in ways that make its function dynamic, not static. Indeed Vol. 2 betrays quite a bit of aggravated anxiety around the symbol itself, which finally works out as an overspill of self-parody, self-reflexive excess. This is a process, not a gimmick that keeps working exactly the same way throughout.

But I actually just find Spiegelman’s prose absolutely, utterly intolerable.

It’s not prose, exactly. It’s comics dialogue and comics narration. (It’s no more prose than are the long, hanging silences of Pinter.)

Noah, I do not presume to judge or dismiss Celan, about whom I know very little and whose work I have sampled in only an iceberg’s-tip sort of way.

Comparing Spiegelman to Celan, even to condemn him, is much more respectful than your really ridiculous plea that what he’s doing is worthwhile because it’s new to comics.

It’s not ridiculous. It’s an important historical point. I happen to value — not to the exclusion of other considerations, but highly nonetheless — formal innovation in art. Formal innovation emerges against the background of an art form’s specific history, and, yes, doing in a given form what no one has done in that form before, and doing it in such a way as to profoundly influence, even reroute, what follows, is an important and noteworthy achievement. I’m hardly alone in this view; indeed the history of art forms is routinely told in terms of formal innovation. That’s not an exhaustive way of looking at art; indeed, being something of a materialist, I’d argue that privileging formal innovation alone is inadequate to the history of forms. But it is an important and inevitable way of talking about changing values in art. Formal innovation is important to me, and it is widely important critically. Arguments about innovation must reckon on the specific historical development of forms, and, in comics criticism, Maus is a necessary part of the historical narrative.

You have a tendency, notable in your responses to Jeet, to dismiss these specificities as not only irrelevant to your interests (fair enough) but also as a kind of oppressive disciplinary boundary-drawing (unfair). I don’t believe it’s oppressive of me to insist on closeness and rigor in the critical interpretation of a comic. At times you seem so determined to demonstrate your independence of the so-called comics fan POV (which you construct monolithically) that you engage in a kind of slash-and-burn criticism that is not only ungrounded in but adverse to careful reading of the material.

But don’t tell me that I’ve violated some tenet of scholarship or criticism because I’m unwilling to qualify my opinions…

Criticism, no, you have not violated a tenet of criticism by venting your opinions without qualification. You may have violated, or more accurately disappointed, my expectations of criticism, but you have violated any sacred tenet.

However, scholarship is another matter. If you insist on trumpeting your refusal to spend more time with the work, then, yes, you are violating one of the tenets of scholarship as I understand it. Of course HU does not propose to be scholarly, usually (I’d say the same about most of the work @ The Panelists), so that’s no big sin. In another context, it might be.

BTW, no one said anything about rereading Maus infinitely. Just more carefully, and with less of an obvious, foregone determination to pillory it.

You may have violated, or more accurately disappointed, my expectations of criticism, but you have violated any sacred tenet.

Error! That line should read:

You may have violated, or more accurately disappointed, my expectations of criticism, but you have NOT violated any sacred tenet.

Ack! You just reminded me Charles to try to get an edit function in the redesign.

Charles, the problem with trumpeting Spiegelman’s formal innovations in terms of comics is that (a) comics has long been fairly backwards aesthetically, and (b) comics, and especially what Spiegelman does with comics, is closely related to prose narratives, so lifting techniques doesn’t look especially impressive. It’s certainly fine for you to point it out, and it’s interesting from a comics-centric point of view if what you’re interested in is disciplinary history. But to say that what he’s doing is great because of those factors; it just seems really condescending to me. It’s like praising Duke Ellington because he was the first (more or less) to use complicated arrangements in jazz. If that was Ellington’s achievement, he’d rightly be forgotten. HIs achievement was what he did with the arrangements, not that he had them.

As I’ve said before, there are different contexts in which to place art. One of them is by looking at the specific disciplinary history. Another is to compare to artists in different disciplines. One way is to look carefully at an entire work. Another is to look at and think about smaller pieces, perhaps in the context of an ongoing dialogue.

In this case…I mean, I have read Maus, some sections of it many times. I’ve read your book with its discussion of Maus. I’ve read Eric’s essay on Maus (a while ago, but still.) I’ve read Ernesto’s essay on Maus. I’ve read other books by Spiegelman. I’ve read autobio comics influenced by Maus. What exactly is the cut-off where I’m empowered to talk about it, Charles? Do I need a degree in Mausology? Or is the issue instead (as I suspect) that I have to talk about it, negatively or positively, in a certain way and with a certain level of respect?

You claim I’m constructing the comics canon monolithically. That’s bullshit. It’s you who claim that I’m out to enrage; it’s you who claim that I”m out to topple idols. I know lots of people who think that Maus is lousy, boring, ham-fisted, poorly written, pompous, and cliched. It’s no big thing to me to say it. Again, if it’s a big thing for you to hear it, that’s not my fault.

And I’m still interested in why you don’t like Celan. Just go ahead and tell us! Celan’s dead, you can’t possibly hurt his reputation, nobody thinks you’re an expert on him…but you’re a smart guy interested in culture and writing, and we’re having a discussion about him. Get out of your comfort zone for once, man.

Charles, I didn’t mean that it was a gimmick or immutable, just that it wasn’t subtle. Because it’s so explicit and because it’s an analogy/symbol, it’s always very foregrounded. It never slips into the background for me. Mutable, but not doubled. I agree with you that he explores the symbol and its complexity and that his treatment isn’t static, but it’s still a pretty direct, pointed symbol and one that isn’t terribly obscure. I also agree it gets at something big and essential and explores that — but aesthetically for me the result of that is something very blunt and loud.

I think this is a risk you always run when you put a symbol in an image. It’s very characteristic of cartooning, but it’s a GENRE of cartooning, not an inevitable choice. European cartooning does it far less. It’s because the symbol saturates the image that it doesn’t work for me. It’s related to Alter’s point about Genesis: it’s too concrete and tangible. Symbols are more concrete than many other devices even when they’re verbal, and when you make them into pictures, and make those pictures so central to the work, I find that overwhelming.

We’ll just have to disagree that it’s not prose! It may be a specialized kind of prose (in which case I would say it’s probably TOO specialized), but film dialogue is prose, newspaper writing is prose, tv talking heads speak in prose. If it’s “ordinary grammatical structure and the natural flow of speech” (per, pathetically, wikipedia) it’s prose. But to be clear, I find representational orality like Speigelman’s intolerable in film too. I’ll be writing about this more in my Alec piece — I find Campbell’s prose utterly delightful.

Well, Caro, what does that do to three thousand years of iconography?

Absolutely nothing, Alex. Iconography is strong symbolism too: it’s iconography because the symbol is foregrounded (although some of it is more subtle than Spiegelman’s, but it’s a related genre.)

Iconography, however, tends to be punctuated into single images or small groups of images, not pages upon pages of narrative. I think when you use iconography as the structuring principle for a long-form narrative, you get something inherently strong, loud, and overt, that I find highly aesthetically unpleasant.

I disagree in the particular instance of Maus. Once you have digested the conceit of animal people, I find that it recedes into the background and is forgotten.

But as Charles suggests, Spiegelman makes a concerted effort to foreground it again once it’s receded. He constantly talks about it, pushes at it (having the characters in Maus masks) etc.

I don’t think it’s a very good defense of the book to say that it’s central conceit doesn’t matter or is forgettable. (And in this case I don’t think that’s actually true.)

Darn; this was on the wrong thread:

Oh. And Hamburger’s translation is beautiful to me because I can read it. A translation is it’s own work of art, and can be evaluated as such. Whether it’s accurate is a separate matter. Celan wrote in German though, Alex, not French.

It does matter, and it’s not so much forgettable as lost to our conscious attention, but remains to color our perception.

Spiegelman’s decision to foreground the conceit every now and then stems, I think, from a very contemporary impulse to lay bare the artifice at the heart of art; if John Fowles or Italo Calvino can, why not he?

I also think he is aiming at a Brechtian Verfremdungseffeckt, not allowing us the comfort of a nice wallow in story. the climax is, of course, when he includes Vladek’s actual photograph at the end of the book– blowing his whole conceit to smithereens. That’s quite daring.

Yeah; Charles makes much of the photograph too, and has a nice bit where he points out the artificiality of the photograph itself (it’s a restaging, and clearly posed.)

I’m not a huge fan of Fowles either, and am ambivalent on Calvino. I tend to think they’re both more subtle and thoughtful in the way they foreground artifice (and not artifice) than Spiegelman is.

As Caro says, and as I argue in the post as well…I don’t’ think Spiegelman manages to figure out a way to translate the things he’s picked up from literary fiction very effectively into visuals. The central visual symbol comes across as very heavy-handed, and undercutting it (often verbally) tends to just call into question the drawn representation rather than getting at ontological questions. The picture too…there’s just something very obvious and leaden about introducing a photograph as real into an illustrated work — and even if it is posed, I think the emphasis is still very much on the idea that *this* is Vladek, posing, as opposed to an illustrated mask.

I think there are comics artists who are more sophisticated in the way they use visuals to ask questions about reality and knowledge. Moto Hagio, for instance, since I’ve been thinking about her recently…in Hanshin she uses repetition of images and elision of images to shuffle identity and exterior and interior; you’re never really sure what is true and what isn’t. The result isn’t unlike Celan; it opens up holes in interpretation which are not so much playful as unsettling…and for me, poetic.

Spiegelman never does that. He asks questions, but they don’t really open up interpretation. They close it down, if anything; as Caro says, the visual tropes are deployed in one-to-one way that is insistent and loud. The line between real and representation is pointed to, insisted upon, but never crossed or blurred.

In terms of Brecht; I think your comparison doesn’t hold up here either. Brecht insisted on presenting the action on stage as false, in order to reveal ideology. You were meant to be alienated from the characters on stage. Spiegelman works in the opposite way. He tells you the action he is presenting is false…*in order to make you sympathize more fully with his dilemma as a writer and a victim.* Maus does not alienate through highlighting artifice. It points to artifice in order to further engage your sympathies.

Only vaguely a propos, but one of my favorite essays on translations, by Harry Mathews http://www.altx.com/ebr/ebr5/mathews.htm

Noah, I disagree with your final paragraph. If Spiegelman wanted sympathy, there are far subtler and more effective ways to get it than depicting yourself as a manipulator and possible profiteer.

Alex…actually that’s false. Rogues and scoundrels are more lovable than just about anyone. Turn on any television drama if you don’t believe me.

Showing your flaws in order to get points for honesty and humanity is basic, basic confessional literature 101.

Spiegelman isn’t bad at it or anything, but it’s neither especially novel nor especially brave.

I think it takes a feat of dulling your senses to not notice that symbolism all the time…but even in more subtle works, if something is coloring my perception, I stay aware of it.

Noah, I never said I don’t like Celan! I’ve just not engaged his work to the degree you have.

The poem you cited deals with such ontological and epistemological difficulties that I think it far exceeds Maus, and also tacks in a different direction. Maus frankly needs straightforward representation to make its points accessible, meaningful, comprehensible. It is doing something far different than the Celan poem.

I don’t fault either Celan or Spiegelman for that.

Reading Celan, really reading him, will have to be a future challenge for me.

BTW, saying that comics have had a history of being backward aesthetically neither elevates nor denigrates Spiegelman. What’s at issue for me is the way he engages comics form and comics history. I find it brilliant. I can see that you don’t.

Hey Charles. Yes, we may just have to agree to disagree. Engaging comics form and comics history is certainly a worthwhile thing for a comic to do. I don’t find Spiegelman’s solution to those issues especially winning. (Alan Moore, on the other hand….)

“The poem you cited deals with such ontological and epistemological difficulties that I think it far exceeds Maus”

That was basically my point…specifically in response to the Priego essay, which was praising Maus (at least in my reading) for its treatment of ontological and epistemological difficulties. I think making a case for Maus on those grounds is really dicey, and I think a comparison with Celan suggests why.

And actually I think you’re comment here suggests why in other ways as well. Maus is, as you say, interested in accessibility and “straightforward representation.” I actually like it most when it just embraces that and tells its story. The self-referential moves seem tacked on, and not very skillfully. But…obviously mileage differs. I think I’d find it easier to buy a defense of the book which argued that it serves to popularize the ontological/epistemological issues in the context of an important and interesting narrative. That makes it a solidly middle-brow work, though…which could be folded into an idea of comics as the current laymen’s literature, in contrast to irrelevant high-brow poetry/lit-fic, etc.

I’ve probably read less Celan than you’re assuming. He’s great fun, but maddening, obviously. On the other hand, there’s something freeing about reading something that you know you’re never going to understand….

I’m coming to this discussion a bit late, and I’m certainly not going to be able to keep up with these early morning salvos (7am? Good Lord!), but the talk has gotten me worked up over some issues.

The idea that Spiegelman emerges from his therapy session “more mature” is a fundamental misreading of that scene. (I’m referring to the discussion that began over at The Comics Grid, but it has its function here. And to be fair, I disagree with both Noah and Ernesto on this.) He returns to what he was before he went to Pavel’s; the mask is still there, the representation of his character changes back from a toddler to an adult, and though he may feel somewhat less anxious, there’s no sudden maturity. In fact, the “Pavel” section ends the most self-consciously meta-textual portion of the book. Spiegelman returns to work, Vladek’s story continues. Pavel might as well say, “Get on with it.”

@Noah: “Spiegelman works in the opposite way. He tells you the action he is presenting is false…*in order to make you sympathize more fully with his dilemma as a writer and a victim.* Maus does not alienate through highlighting artifice. It points to artifice in order to further engage your sympathies.”

If you read that moment when “Artie” leaves Pavel’s as a moment of advancing maturity instead of an ambiguous return to functionality, I can understand why you’d see these tactics as some kind of plea for sympathy instead of a layer of self-interrogation. But for me, the self-consciousness of the book is not soliciting pity and adulation, but criticism and judgment of its author, encouraging the very alienation you experienced, Noah. That is the risk of his use of self-reflexivity, and there’s a strong example of it at the end of the very first chapter—hardly tacked on. Spiegelman critiques his own “cleverness” as the book proceeds, and as he has said often, the point of the cat/mouse metaphor is that it’s ultimately a failure. It falls apart upon closer examination and narrative propulsion.

The use of admitting and even highlighting one’s own weaknesses is certainly used often in any number of art forms, but equally as often—especially, it seems, in memoir—there is ultimately a redemptive moment in the narrative for that character or person, which often to me does seem cloying and self-aggrandizing. What here would be Spiegelman’s redemption? Finishing the book? That’s some pretty shaky extracurricular ground to be standing on.

I don’t see the benefit of making formal comparisons between a once-serialized graphic novel and a poem. A book-length comic will almost always seem leaden and clumsy compared to a poet like Celan, indeed, to just about any good poet, even if there are theoretical and thematic similarities between the two. (Hell, especially if.) Comparisons to prose are only a little better, but my beef with so much comics studies and criticism comes from this kind of reaching for supportive legitimacy on the one hand, and for baseball bats on the other, ignoring the formal uniqueness of comics. Maus and its caricature/iconography certainly calls back to Herriman and the anthropomorphic traditions in popular culture more than it does either Celan or someone like Borges, and there’s plenty to unravel there. Herriman had a taboo subject he couldn’t speak to, as well.

Sorry, but this kind of reductive either/or thinking strikes me as myopic and impotently hierarchical. The Ellington comparison is particularly short-sighted here, since The Duke is remembered for both his formal innovations and what he did with them, at least among the musicians and music critics I know. I suspect it will be same with Spiegelman. I fail to see the interest in arguing whether or not Spiegelman’s use of counterpoint was better than Ellington’s. It’s even worse, I think, to apply this approach to a reading within a work as is going on here with Spiegelman. I’m perfectly content with acknowledging his solipsism, sympathizing with his grief, and criticizing his perception of his own victimhood all at the same time, and I’m grateful to him for writing a work of art that gave me such a rich experience.

Poetry to me isn’t about understanding only. One of my favorite poets is Herberto Helder. He said that: “The Truth is the permanent repositioning of the enigmas.” Poetry is a feeling provoked by words. If we understand these words completely we’re having an intellectual experience, not a spiritual one. I don’t know if I’m making any sense though. Paul Celan thought that his most famous poem said too much. These (illustrations) paintings by Alselm Kiefer: http://tinyurl.com/68q2a3t http://tinyurl.com/4qwyl9n http://tinyurl.com/4ncxhk8

say too much too, maybe, but I like the materiality of the straw (followed by an index of combustion) and the referentiality of the painted flames. Maybe we can read something here that’s not quite so obvious: painting stands for the mythological quality of ideology. In the end Shulamith was killed by ideas as much as by Zyclon B. Here’s the poem: http://tinyurl.com/4m6btnl

That said I like _Maus_ enough to put it in my personal comics canon. I’m not deluded about its greatness though…

Hey Robert. Thanks for correcting me about the maturity bit. It has been a while since I read Maus.

I wasn’t kidding when I said that showing your faults is confessional writing 101. I was literally told to do just that in my creative writing course at Oberlin. Amy Hempel was visiting; she had us read a story in which she betrayed her best friend who was dying. There wasn’t any redemption especially; story ended when she left her best friend to die. She explained that you engage the reader’s sympathy more when the protagonist is flawed. I see nothing in Maus which contradicts that procedure.

You’re not at all alone in your belief that comics should only be compared to comics; I mentioned that this is a common prejudice above. I think it’s an attitude which is defensive, self-defeating, and depressing. Are comics their own little ghetto, where only comics standards can apply? Or do they have something to say to art and the world outside their particular fiefdom? Why anyone who cares about comics would choose the first over the second is something I have difficulty understanding.

The interest in comparing Spiegelman to artists in other arenas and eras is to better understand what he’s done and how successful he was at doing it. Celan confronted similar problems of tragedy and representation; Duke Ellington confronted similar problems of working in a despised medium with (by some standards) relatively undeveloped formal qualities.

The point about Ellington, incidentally, is that nobody praises him for being the first to bring classical elements into jazz. (Or not many people anyway, thank goodness.) The reason they don’t praise him for that is that that would be condescending to him and to jazz. They praise him for adapting some elements into a new idiom…an idiom which, not incidentally, has had a huge effect on the classical music he borrowed from.

Do you believe that Maus’ innovations (if such they are) are going to have a profound effect on the literary tradition that he borrowed them from? Have they done so already? Do they have any sign of doing so in the future? A conversation in the arts that is all one way is not a conversation of equal partners. And comics will never be an equal partner as long as it sees any comparison with any other art as an unfair demand, rather than as a challenge to rise to.

Domingos, I think your take on poetry makes sense. And I think I agree with Celan too; I like his shorter more elliptical poems better (though that one is nice too.)

Thanks, Noah, for your reply. Your explanation of the Duke comparison made more sense the second time around, though I’m still not entirely in agreement. Certainly no one should praise him for making jazz “better” by making it more classical; not only is it, as you said, insulting, it’s also pretty short-sighted about the brilliance of his fusion. But he is still appreciated for his formal innovations, just in the more nuanced way you describe, and there’s no reason this appreciation can’t comfortably stand next to the success and qualities of, as you said, the new idiom he created.

I’m not against comparison between the arts. As I said in my post, I’m leery of “formal comparisons” between those forms when there’s no recognition about what’s unique in each, and I’m particularly perturbed when one “fails” to do what the other can, and when that “failure” is used to place an artist on the leader board. If avoiding these tactics is too-careful criticism, so be it.

The way out of the fiefdom is not necessarily to make war with the king. To even see it as a fiefdom is basically a perception guided by profession and media, and not by what I’d consider particularly good criticism. If comparing comics to only other comics is defensive and self-defeating–which it is–then might not the same be said about valuing comparisons of comics to prose-only forms of literature, fiction or memoir? In that same post about Ellington, you said that “comics, and especially what Spiegelman does with comics, is closely related to prose narratives”. In the broadest sense, yes. So do movies and television. But movies have actual speech, and television is decidedly episodic. Must we always find some literature reference by which to judge them?

Do I believe that Spiegelman’s innovations are going to have a profound effect on the literary tradition he borrowed them from? Forgetting for a moment my hesitations about what we mean by profound, my answer is yes. They already have. But the literary tradition I have in mind is the graphic narrative/comic book/whatever we’re calling it today. I know this plays a bit into your argument. But even if Ellington had a profound effect on classical music, we wouldn’t say he had a profound effect on rock music, let alone film or the visual arts. And we certainly wouldn’t devalue his work because of this.

The bottom line for me is simply that comics have a unique language due to their blending of word and image. This doesn’t mean they must exist in their own little codified world, but neither does it mean that they have to match up against Borges.

As for Amy Hempel, I’m envious you were in a workshop of hers. But I have to ask, the story you mention, was that fiction or non-fiction? There again the expectations, conventions, etc., are different. And you and I may agree, perhaps, that the word she ought to have used was empathy?

Noah:

My take on poetry is also my take on painting. That’s why we can’t judge a painting by a small image on our small screen, let alone by how we translate its ideas into words. Those Kiefer paintings need to be seen to be believed. I also thought a little about why does he paint a plowed field? Maybe because the ashes have fallen to earth long ago?…

Robert:

When I participated on TCJ’s messboard I always compared comics artists to artists in other fields. The answer always was: you’re comparing apples and oranges (and they would say this even when I compared some hack to an alternative comics star). That may be, but my answer was (and is): why not?, they’re both fruits. To be an artist (and I’m including writers and musicians) means to create something and achieve some goal. People may disagree about what these goals are, but they shouldn’t look for them in one artist and not the next one. This means double standards. For instance, when people look for complexity of the characters in alternative comics (dismissing the cardboard) why do they say nothing about the subject when they’re writing about a superhero comic? Apples and oranges? Really? I didn’t know that there were no characters in mainstream comics… (Adrian Tomine has been consistently a victim of this.) Some devices cross art forms and genres.

Well, the TCJ messboard will do without you. It will in fact, do without anyone. It’s dead.

The Hempel piece was I think technically fiction, but it was confessional and heavily based on life. (And while I was wowed at the time, I really don’t like her writing at all anymore. Spiegelman’s better, I think.)

Ellington’s had more of an effect on rock music and than you’re letting on. Huge influence on Steely Dan, for example; a really central and seminal rock band. I’m pretty sure he’s influenced film as well. Jazz rhythms and aesthetics have been a mighty inspiration across pretty much all the arts. Certainly for film and visual art.

It’s somewhat like hitting a gnat with a bazooka to compare Spiegelman to Ellington, admittedly. But…Spiegelman has a comparable stature in comics that Ellington does in music. They both work in a mixed low art/high art idiom….. I don’t think it’s so unfair.

Comics may have a unique language. But you have to prove it, baby. And you can’t prove it without comparison, can you? How would you know it’s unique if you don’t look at other art forms? If Maus has a unique innovation to offer, then it has to show it’s doing something different, and presumably better, than other art forms. To see that you have to put it next to, for example, literature. I don’t see what Spiegelman is doing as a unique innovation. Neither have literary artists, as near as I can tell. Comics certainly may make unique contributions…and I think some have. Maus? I’m not convinced.

Can we have an HU thread with an overall look at the history of the TCJ message board? It was a pretty important and vital part of comics discussion for many years. Where aficionados could start their own threads on whatever subject caught their interest. Instead of waiting to give feedback on whatever a small group of chosen contributors decided to write about.

It had dwindled significantly, yet its being rendered inaccessible for what felt like an eternity (weeks?) during the transition to the new online “Comics Journal” is what really made activity there plummet.

Its killing goes along with the inexorable tide that sweeps away public spaces where messy, freeform engagements and discussions can take place, for far more controlled ones… (Some related thoughts at http://curiouscatherine.wordpress.com/2010/12/05/networked-publics-and-civic-spaces-or-why-i-dont-want-to-end-up-making-important-decisions-while-avoiding-adverts-for-viagra/ )

Guys, I think it’s still there, just without a link from the homepage at the moment. I don’t have a link, but I got incoming traffic from there after the new site launched….

Mike, if you want to put together something on the tcj.com messageboard history, I’m game. You can email me: noahberlatsky at gmail.

No, Dan Nadel made it clear in an interview at Comics Reporter that the messboard was kaput for good.

The TCJ messboard was where I first yelled at Noah…sigh…

Ah, my mistake. Seems like a shame….

I’m all for messy, free-form discussions. Sounds like I missed something grand at TCJ.

Again, I’m all for comparisons between artists and their work, and Domingos, I’m not in favor of just shutting down a conversation with some generic “apples and oranges” claim. I hope I haven’t given that impression. I just believe formal comparisons need to be made with distinctions in mind as well.

Your example about alternative and mainstream characterization is far more applicable and relevant, I think, than comparing a graphic memoir to a poem. There’s no reason why a certain audience shouldn’t want for richer characterization in mainstream comics, even if the market and its other audiences don’t mind the lack thereof. But Love and Rockets has different goals in mind than, say, The Incredible Hulk. Just like Sarah Glidden’s How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less has different goals in mind than L&R. I just think those should be recognized in the discussion, too.

If you visit the blog linked to my name here, you’ll see a recent post I made about Strangers in Paradise and dialogue. (Keep in mind, please, that the site is at this point mainly a supplement to the undergraduate class I teach.) I’m discussing the attributes of dialogue we tend to value in most contemporary American fiction and how SiP, and maybe comics, resists those. But I make a crucial distinction that comics can do this because of their imagetextual nature. I’m also borrowing from some basic feminist theory in that article. I hope it’s an example of what I’m talking about here, making distinctions and connections without being too narrow, or too broad.

Noah: Methinks you overestimate the Dan’s place in rock, but that’s a minor quibble. I do hear some of Ellington’s influence in their work, which I hadn’t thought about before, so thanks for pointing that out.

Again, I’m not against the comparison-making, and of course you need to look at other forms in order to understand the innovation. I’m less interested in “better”, though, and I think that’s where we part ways on this particular subject.

“I don’t see what Spiegelman is doing as a unique innovation. Neither have literary artists, as near as I can tell.”

Click here to listen to a discussion between poets Norman Finkelstein and Harvey Shapiro talking about the legacy of Objectivist poets (Zukofsky, Oppen, Reznizoff, etc.): http://www.writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/x/Finkelstein-and-Shapiro.html

In the last ten minutes theres a discussion about the difficulty of creating art about the Holocaust. Finkelstein particularly commends Maus as a solution to the well known Adorno problem of creating an aesthetic work about the Holocaust. This is one example of many that can be pointed to.

Yeah; academics often aren’t so interested in better/worse. I think that’s a problem with academic criticism, actually.

Steely Dan is huge! Massively popular, and I think still an important influence on lots of alternative bands. Waylon Jennings covered them; Faith Evans name-checked them. That’s a pretty broad reach, I think.

They cover an Ellington tune on one of their albums…can’t remember which one right now though….

Thanks for the link Jeet. That just kind of depresses me, though…but I guess I shouldn’t expect more from contemporary poets. Compared to Carolyn Forche, Spiegelman looks like a genius, sure enough.

To sum up the debate so far:

Noah: Litarary artists don’t think Spiegelman has made an artistic innovation.

Jeet: Here are some literary artists — poets — praising Spiegelman for making an important artistic innovation.

Noah: Poems suck.

It’s always good to change the terms of discussion. You don’t have to think about your original position that way.

Also: “Comics may have a unique language. But you have to prove it, baby.”

Um, there have been many attempts to prove it, most notably Charles Hatfield’s Alternative Comics. I’m pretty sure you’ve heard of this book, since HU hosted a long (and at times very useful) discussion about it. But that’s the problem with your position in this post and others of this sort. I’ts predicated on pretending that the vast body of criticism discussing these matters doesn’t exist and doesn’t need to be taken into account.

It’s East St. Louis Toodle-oo on Pretzel Logic.

Clever reference to the album title by Jeet.

Also, the debate isn’t between people who think comparisons between forms should be done (Noah, etc.) and those who think they shouldn’t be done. That’s a false dichotomy. The argument is that comparisons when done should be done carefully and with an appreciation of historical and formal differences. To my mind the Celan/Spiegelman comparison makes no sense for two reasons:

1. Maus is a narrative while the Celan poem is a meditation.

2. Celan lived from 1920 to 1970 (in Europe). Spiegelman was born in 1948 and has lived most of his life in America. So for Celan any poem he writes is a reflection of events in his own lifetime. Spiegelman narrative of the Holocaust is explicitly a narrative of an event that happened before he’s born, of a tale he heard from his parents and their generation (which is one of the many reasons behind the anthromophism: the Holocaust first came to Spiegelman as a story heard as a child.)

This doesn’t mean that any comparison between Celan and Spiegelman is impossible, only that it requires a far greater historical and cultural sensitivity than you are willing to deploy. Given the larger tenor of your criticism it’s hard to escape the feeling that you don’t deploy such a sensitivity because you have a pre-determined judgement that you’re going impose no matter what the evidence. A hanging judge rarely makes for a good critic.

I like Charles’ book! I think it has interesting contributions to make on that front, and it certainly focuses in interesting ways on the back and forth between text and image. However…I don’t think it actually works to put Maus in the context of comparable works of literary fiction. As a result, I don’t think it actually makes the case for Maus as “unique” — other than in the trivial sense that any work is unique. I think Eric’s book may try to make more steps in that direction (though I haven’t read it; need to wait for publication just like everyone else.)

I’m still not especially convinced that contemporary poetry or literature has looked to Maus for guidance in anything in particular…especially not on a level comparable to Ellington’s influence. But! I’ll try to listen to your link, and maybe it’ll convince me. And yes, I’m conceding your point; poetry really would be helped by being more like Maus. That’s as much a comment on the state of contemporary poetry as on the greatness of Maus, but I think it is useful to be reminded that sometimes you can set the bar too high in these matters.

And come on Jeet — there’s not a “vast body” of worthwhile criticism on comics. Would that there were.

Well, the whole question of “influence” is a bit of a red herring in a way. I think a work of art can have a wide influence without being very good. You’ve expressed disdain for Hemingway but there’s no denying that Hemingway’s stripped down writing and dialogue had a huge influence not just on fiction but also film and theatre (and perhaps even comics).

Arguably the most influential cartoonists in terms of changing other forms were Ernie Bushmiller (Nancy is everywhere) and the nameless hacks who did the covers of romance comics (which are also everywhere).

1. I don’t see why narratives and meditations shouldn’t be compared. Especially when the question at hand is ontological and epistemological complexity, issues which can be addressed in either.

2. Yes, Celan is closer to the events. So this means Spiegelman should be given more credit for a less searching examination of ontological and epistemological issues why exactly? He can’t possibly be as insightful because he didn’t live through it? Or what?

I was discussing a particular issue brought up in a particular analysis. The comparison works perfectly well for those purposes. You don’t need to talk about everything in one blog post.

Just to return to something Charles said; I have no problem with careful scholarship. I think deploying it in order to suggest that only scholars can talk about art is deadly for scholarship and for art. As an example, if you have an actual argument based on either of your two points which contradicts or addresses what I said in the post, by all means bring it out. Otherwise, you’re just a wikipedia article crossed with a school marm, you know?

Along those lines, it’s true that a hanging judge rarely makes a good critic. Are hanging judge’s less likely to make good critics than sycophants? Less likely than even-handed, impartial observers? Good criticism’s just rare in general I think is probably the issue.

Jeet — yeah, that’s an interesting point about influence. Of course nameless pop can be very influential in various ways….

Comics has had a far more powerful effect on visual art, I’d say, than it has on literature. I have really mixed feelings about Chris Ware, as you know, but he’s huge; definitely an important figure in the visual arts. And comics in general are picked up in various ways by that world.

Spiegelman’s just a much more literary figure, for all sorts of reasons. And the arguments about his worth (like Priego’s) tend to focus on literary qualities. I think those qualities tend to pale if you look at actual literary works, is the thing.

I find Ariel Schrag much more sophisticated and interesting in those terms — which I know will provoke howls of rage from everyone. But there it is. (Charles Schulz too.) (I mean, I find Charles Schulz more sophisticated, not that he will howl in rage.)

“Comics has had a far more powerful effect on visual art, I’d say, than it has on literature.”

In general that’s true but it’s also the case that there hasn’t been as much attention to the actual impact that comics have had on literature. I’d argue that there is a tradition of highly visual writing that has been strongly influenced be comics (and also film): Nabokov, Updike, Davenport, Flannery O’Connor, Tom Wolfe, Nicholson Baker, Chabon, Lethem. It’s not just that these writers incorporate comics thematically (although some like Chabon and Lethem do) but rather that their way of writing takes its coloration and verbal zest from comics. Just as theire is such a thing as “Pop Art” I also think there is a thing as “Pop Lit”. Often these writers create “flat” secondary charcters who are very comic strip like.

I’ve written about this a number of times. See here: http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2004/mar/20/fiction.johnupdike

and heer http://sanseverything.wordpress.com/2008/01/30/guy-davenport-the-writer-as-cartoonist/

As for Spiegelman’s influence on literature — perhaps hard to trace althought I think he was an inspiring force behind Yann Martel’s (not very good, alas) Holocaust novel Beatrice & Virgil. Perhaps one place to look for Spiegelman’s impact would be in the general trend towards post-modern Holocaust fiction, much of which was written in the wake of Maus (and again, as with Martel, I’m not saying this stuff is good).

I’ve written about that too:

http://www.walrusmagazine.com/articles/2010.06-books-shoah-business/

Finally — I don’t think Spiegelman’s impact has been purely literary. There’s a whole tradition of formalism in comics which owes a lot to Spiegelman’s various storytelling strategies: Ware, Richard McGuire, and even lan Moore (whose work from the 1980s can be seen as a popularizing of Breakdowns in the same way Dashiell Hammett popularized Hemingway).

Finally — really finally this time — it occurs to me that you’re in the weird position of arguing that Spiegelman is over-rated and that he’s not been influential. It seems to me that these two claims work against each other.

Schulz is the Ellington of comics.

So there.

Robert, could you say a little bit more about the feminist theory in your post on Strangers in Paradise, pleasethanxmaybe?

Robert–

I’m curious, too. I look at that page you focus on, and I keep getting distracted by the expectation that I’m going to see some naughty bits–either the blonde’s towel is going to fall off, or the brunette’s nightie is going to get ripped in a revealing fashion. And I don’t think that response is divorced from the cartoonist’s intent.

Noah- Steely Dan is huge! Massively popular, and I think still an important influence on lots of alternative bands.

Steely Dan certainly has plenty of fans among the general public and musicians. But as far as critics goes, they may be praised to an extent but they’re not part of the central pantheon. And for good reason, I think. Their overly-polished sound belies their sincere jazz influences, pretty much to their music’s detriments. But I may be in the minority about this.

Okay, see, if you’re going to dis Steely Dan, you’re not allowed on the blog. I’m sorry, but I have to have some standards.

Jeet; Spiegleman’s over-rated in comicdom, and hasn’t been very influential outside comicdom. No contradiction!

Otherwise, thank you for those links; I’ll try to get to them. I’m badly backed up today….

I don’t know what Noah was meaning by influence, but for me there’s a difference between the claim that comics has influenced “literature” and the claim that comics influenced a specific literary writer. For the more general claim, I’d want someone to identify a modality of literature that wouldn’t be possible without comics having come first.

Like Beat writing’s relationship to jazz. Beat writing is jazz in prose. What’s the literary phenomenon that’s “comics in prose”?

Not that there has to be one, but that’s what I’d mean by “influence on literature.”

(I’m personally hesitant to draw parallels between comics and jazz because I think jazz is more specific than comics. I’m very resistant to critical and theoretical efforts to make comics as specific as jazz: I find understandings of comics that emphasize how dynamic and flexible the form is, how different they can be from each other, more compelling than understandings that try to identify some common aspect that connects them all.)

So while I think it’s certain valuable to know that a specific artist was influenced by comics (even specific comics), I don’t know that we can make any general claims from that. There’s no reason that a writer (such as, say, Delillo, or Dos Passos) couldn’t be inspired to highly visual prose by looking at painting or film…

There’s no reason that a writer (such as, say, Delillo, or Dos Passos) couldn’t be inspired to highly visual prose by looking at painting or film…

The poet John Ashbery certainly did it with Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, which is one of his most lauded efforts.

Yeah; Ashberry has a sestina about Popeye too. (And no, I don’t like Ashberry especially, though he’s certainly impressive.)

The pop art appropriation thing is pretty different than the beats and jazz though, right? I guess because it feels like appropriation rather than inspiration; the sense of taking something you found lying around and repurposing it, rather than being mentored by another artist.

Comics has long been the first; instances of the second are dicier.

Noah- Okay, see, if you’re going to dis Steely Dan, you’re not allowed on the blog. I’m sorry, but I have to have some standards.

Great! Let me escalate this further- Tom Petty > Steely Dan

I believe it was William Burroughs who told them they’re too smart for the idiom they’re in. But it’s not that that’s necessarily the heart of the matter or even the problem. Even to this day listening to their LPs it’s readily apparent how state of the art their productions were at the time. And definetly to a fault.

Now I suppose if I knew how to read music or if I paid closer attention to their lyrics maybe I would warm up to them, but there would still be their overly precise musical approach to deal with. Are they better live?

I think Joni Mitchell remains the nonpareil example on merging modern pop high values and technique without choking the life out of her music. For one thing, a lot of the musicians she used were even more accomplished than the ones SD used.

Yeah, see, I love the precision; the ridiculous artificial soulless sheen. Whether it’s the long vacuous emptiness on Aja or the funky burned out ironies of some of their other albums…

I much prefer my soulless white rockers to embrace their soullessness. This is why Tom Petty is such a wretchedly abysmal travesty. He’s trying to imitate the Byrds imitating Bob Dylan imitating some quavering icon of authenticity; barf barf barf.

Steely Dan, though, says fuck the authenticity. We are going to take this and transcribe it and polish out all the joy, and the polishing will be a joy in itself.

They remind me of June Christy a little, in a roundabout way. So does Joni Mitchell, more directly. Both favorites as well.

All better than Maus! (Well, not Tom Petty. Tom Petty really is utter crap. But even he is better than Shadow of No Towers.)

It’s official: from now on at TCJ site every newspaper comic that was published, say, until the forties, is a work of genius. Art Spiegelman will be pleased.

But how do they compare to Steeley Dan, is the question? Or Tom Petty?

Oh, they’re much, much, better! We’re not allowed to compare though, so, we’ll always be in dark ignorance of the fact. It’s a real shame!…

“Yes, Celan is closer to the events. So this means Spiegelman should be given more credit for a less searching examination of ontological and epistemological issues why exactly?” It’s not a question of more credit or less credit, it’s a question of differences of experience. An “ontological and epistemological” examination of your own experience is going to be different from an “ontological and epistemological” examination of stories that you heard from your parents. That explains the narrative strategy the Spiegelman adopted. Also, because he’s writing a long narrative rather than a focused meditative poem, Spiegelman’s examination of “ontological and epistemological” are threaded through the work rather than focused and localized in a single spot. To put it another way, both the Celan poem and Maus are about what gets necessarily repressed even in the act of telling or how representation creates its own silence. But Spiegelman’s dealing with these issues comes in a variety of narrative forms, not just the now familiar use of animal characters but also in things like the stylistic contrast between the the “Prisoner of the Hell Planet” sequence and the rest of the work, the diary like hand-writing (evoking the missing testimony of his mother which is destroyed), the use of photos or evocation of familiar photos in the drawings. Maus is a very complicated work and the best criticisms of it — I’m thinking here of Hillary Chute’s essays — grapple with the complexity. Your post by contrast is just a typical example of jerk-off blogging. Perhaps I went too far in speaking of a “vast body” of worthwhile criticism, but the fact is there are worthwhile critics like Chute and you’re postings are notable for their complete unwillingness to engage thoughtful with the writings of writers like Chute. It’s easy to win arguments in your own head if you don’t actually engage with real opponents. As I’ve noted above, you did host a (sometimes) useful symposium on Alternative Comics, but I’ve never seen any evidence that you’ve internalied any of Hatfield’s arguments or integrated them into your critical practise.