In her article on Graphic Journalism, Erin Polgreen states that:

“[Travelogues] are often meditative explorations of a foreign landscape in which the reader unpacks their cultural baggage with the author, exploring a strange land with them. The key here is in viewer identification: The comics creator has a strong voice leading the narrative, and we trust them to impart facts and dissect stereotypes for us. Sarah Glidden’s How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less is a near flawless example of the travelogue. Glidden isn’t going for an objective non-fiction work here, which can seem counter-intuitive to journalists. Rather, she’s looking to use her experiences as a lens for dissecting her own cultural (mis)perceptions and takes the reader along for the ride.” [Emphasis mine]

There are many words which come to mind when I think of Sarah Glidden’s How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less, but “flawless” doesn’t even come close to capturing the essence of any of them.

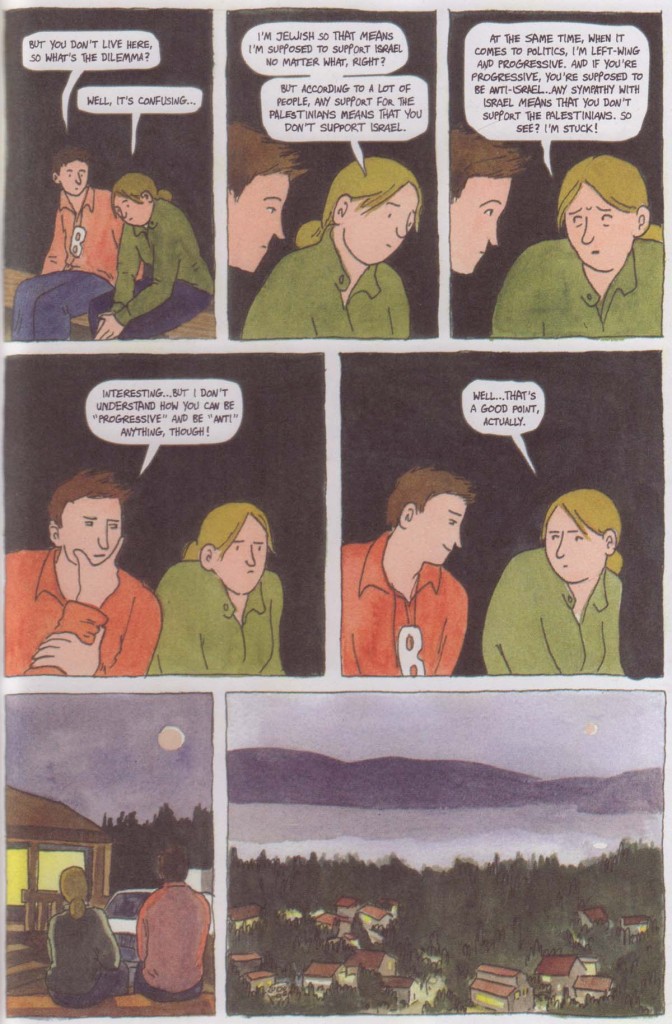

An overwhelming emptiness developed in my gut as I was reading this slim volume of tightly arranged panels depicting a young woman’s frankly insipid account of her first trip to Israel on a “Birthright Israel” tour. Glidden’s comic condenses the “promised land” into a series of flat, non-descript images and dialog sequences. Hence Masada becomes a mound of amorphous light brown soil, its history and controversies distilled to a shallow recital comparing the works of Josephus to her guide’s Zionist spiel. Would that she had read better books and developed a better mind for such analysis.

Where Matisse once suggested that “one square centimeter of any blue is not as blue as a square meter of the same blue,” Glidden proposes that a systematic dabbing of color will do the trick. Her vistas are almost infallibly debased to non-entities. Here a village landscape becomes only a momentary pause — an empty space — and quite secondary to the dialog preceding it.

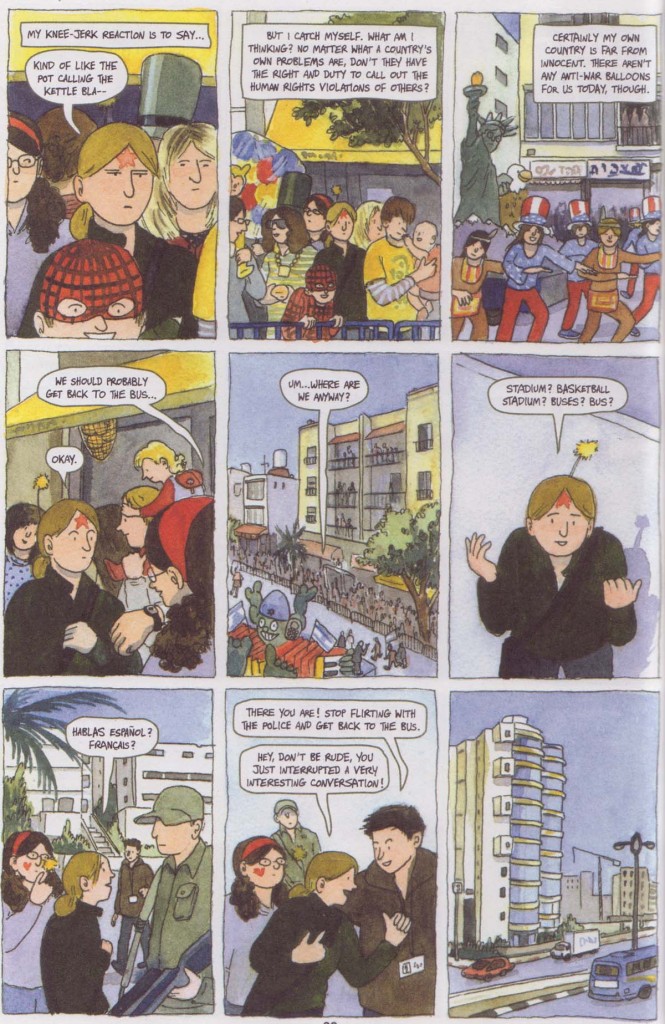

The following montage of a street parade has much the same problem, passing fleetingly before our eyes like a colleague’s holiday slideshow.

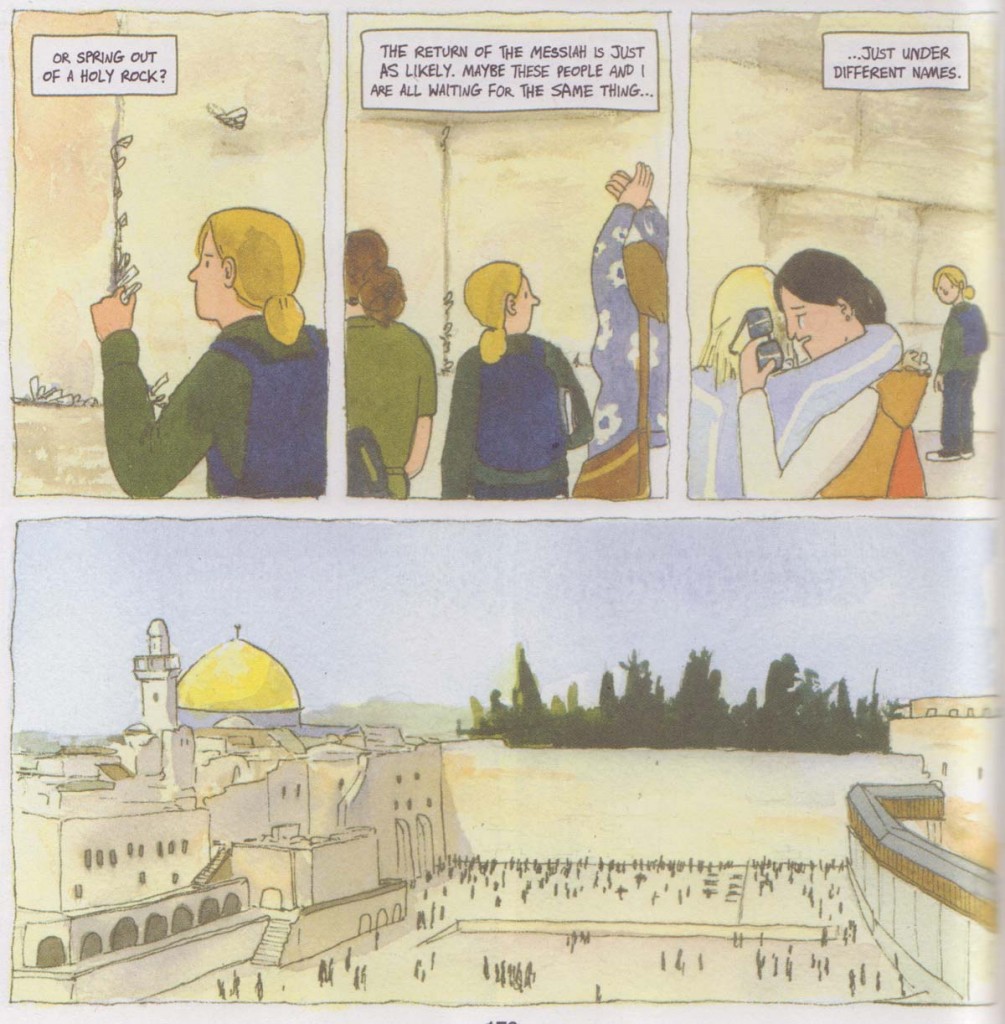

Only close to the Western Wall and the Dome of the Rock do we see a some recourse to the establishment of atmosphere and place, though still to somewhat hollow effect.

Once free of the strictures of the tour (and in the final chapter of the book), the cartooning which was once crudely serviceable begins to display a bit more polish, a dividend from weeks of practice and, perhaps, a process of trial and error. A more skillful practitioner might have used variations on the nine panel grid to engineer some points of conjunction and disjunction between text and image, but Glidden uses this device largely to preserve the steady voice of the storyteller and hence an effortless flow in her account. This is a hallmark of the plain narration advocated by autobiographical stalwarts like Harvey Pekar and his ilk. As such, Glidden’s authorial voice resides largely in her simple drawings and not in whatever talent she has for narrative or language.

What follows is a summation of Glidden’s entire experience (and conclusions) in the form of a series of conversations between the author and various people: citizens, both young and old, who have made Aliyah; a progressive rabbi delivering a message of reconciliation and calling for a striking of archaic laws from the Talmud; and, finally, an Israeli with whom she finds the peace to disagree. Those who have a place in their hearts for Glidden’s comic will undoubtedly point to these exchanges as the basis for their affection; the author’s heart always on her sleeve, her emotions ever on tap, her youthful idealism and barely formed intellect crushing all before her. This is a vision of comics journalism as a mediator for those who have little interest in reading.

I was about three quarters of the way through this comic before I realized that there was a fatal flaw in my approach to this comic. I was half expecting a travelogue in the tradition of Theroux if not Levi-Strauss. But the potential reader will need to reorient herself to the requirements of this cartoon journal for the best results. It is altogether more pleasing if one sees it as a self-lacerating memoir impaling the author’s younger and more foolish self (of course, Glidden recently celebrated the revolution in Egypt with all the superficiality of a 10 word Twitter missive, but I suppose that too could be seen as self-satire.)

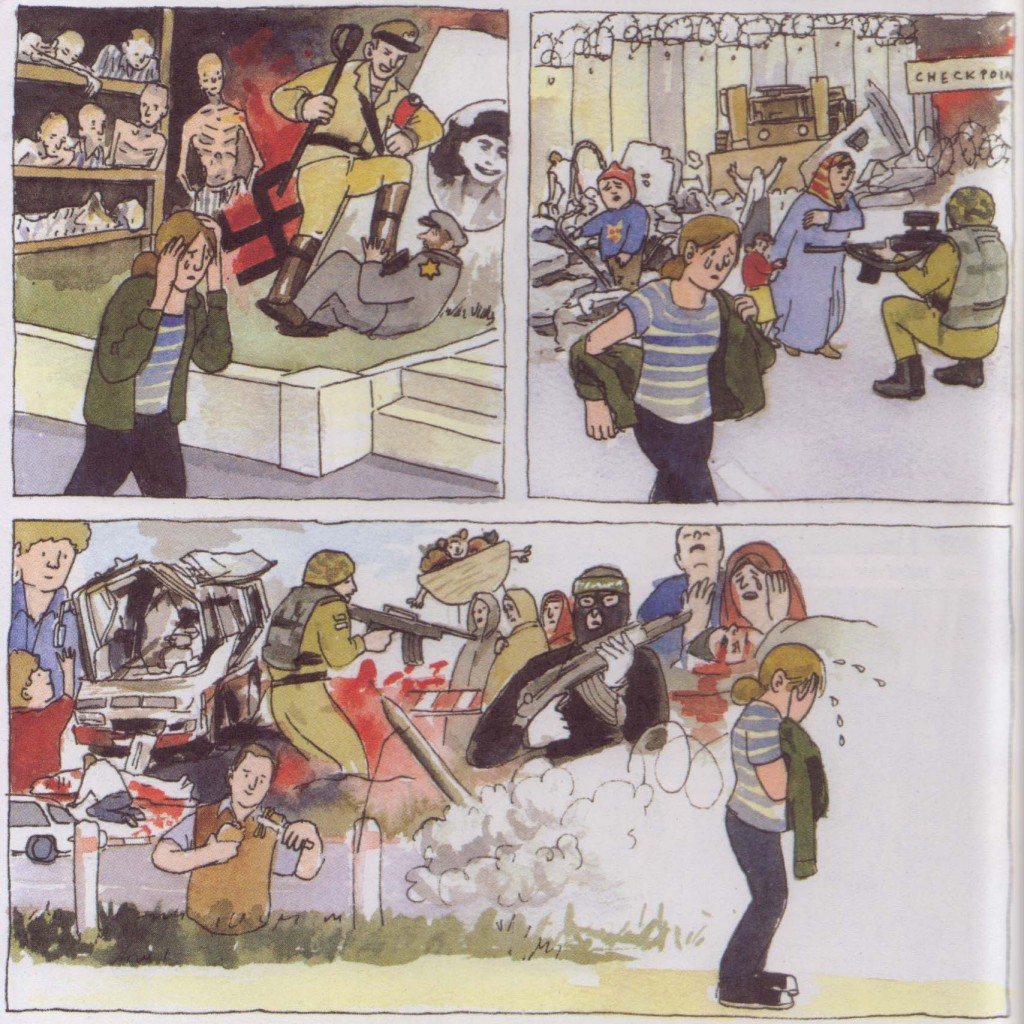

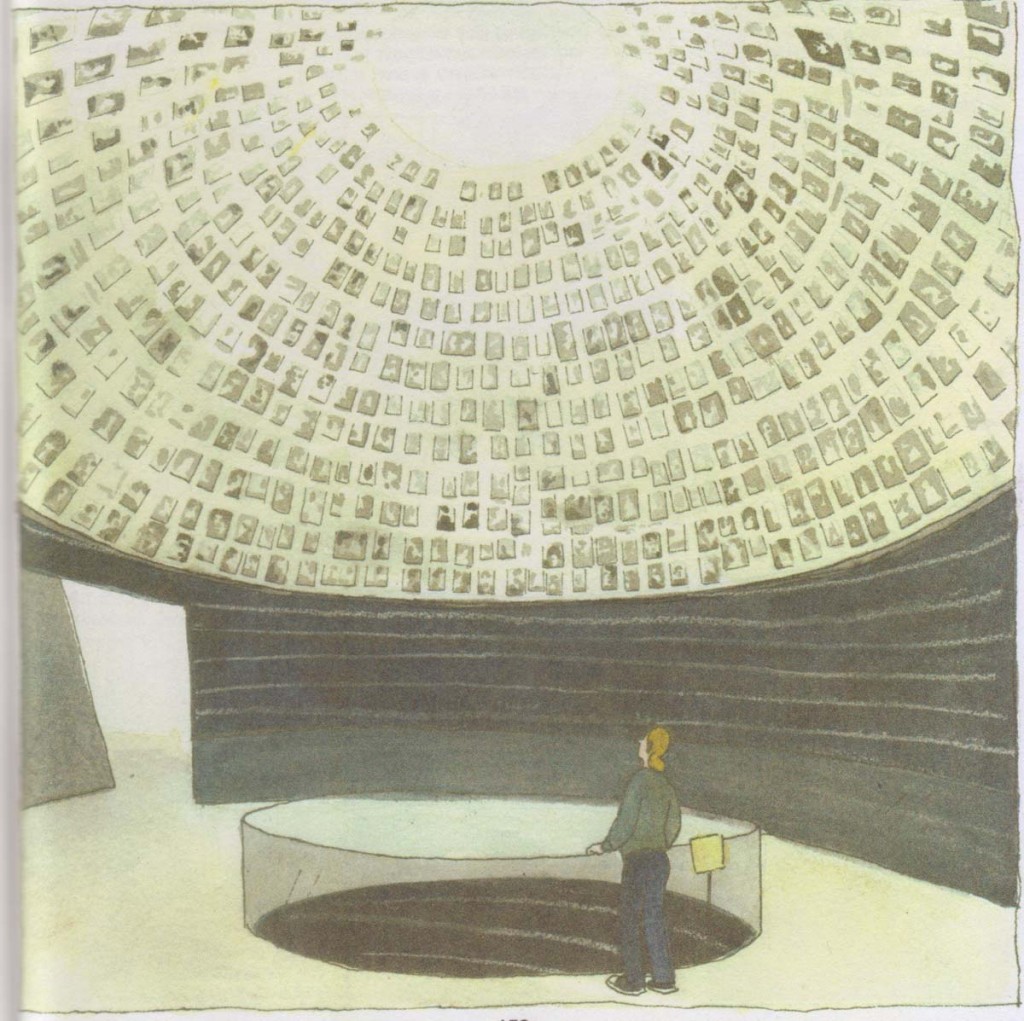

Nowhere is this more evident than in Glidden’s visit to Yad Vashem. The author is justifiably irritated by one of the more prevalent experiences you might find on a package tour — the headlong rush through a famous museum in order to get to a meal (or some shopping). Yad Vashem is quite naturally reduced to that complaint, probably a purposeful disclosure of her rather mean spirit at that point in time.

The guide’s voice becomes a consistent drone, and the sights and sounds of the Holocaust distilled into an understated bitching session.

When all is over and she is given some time to herself, a moment of tranquility in the Hall of Names; Glidden’s tribute to what the Holocaust experience is all about:

What lies beneath this is of course much more insidious and encapsulated in the following sequence of panels:

Here Glidden yearns for the “true” Holocaust experience; to connect and emote with the inhumanity dealt to some 6 million Jews — she wants to be that crying child in the group in front of her. Perhaps she wanted to be struck with awe at the incalculable evil and misery; to feel deep in her heart of hearts the tragedy of it all.

Like a friend who once told me eagerly about his tour of Auschwtiz, this is Yad Vashem as an amusement park ride; that all too familiar cry of, “What can I get out of it,” from cattle on a drive through unfamiliar territory. More damning than the reams of sexposès or masturbatory fantasies in the indy comics of the early 90s, for here Glidden reveals herself as a tourist and travel writer with absolutely nothing to say. That dullness captured in the ironic title of her book — How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less — for the creator knows full well that the country of her visitation is impossible to capture in that period of time. Glidden’s comic is a work of self-condemnation; a “warts and all” cautionary to all those who would seek to traffic in their trifling insights, for therein lies undistinguished banality. It is the rotting carcass of the autobiographical genre in comics.

Oh god. When I read that panel “how can a progressive be ‘anti’ anything?” I wanted to hurl the copy of the book I had borrowed from the library against a wall.

Unfortunately, by posing as a “skeptic” Glidden’s complete purchase of what the Zionist propaganda machine is selling is somehow given the mark of authenticity.

I viewed what Glidden was doing in this book as a form of conversion experience narrative. From my review at tcj.com:

“As a result, Glidden feels both shame and comfort in her trip to Israel. Comfort in traveling to a foreign land yet being welcomed as One Of Us, and shame that she actually feels that way, that she in some respect has fallen prey to the “magical thinking” of being in the Holy Land. The philosopher Slavoj Zizek has a concept that he calls “belief before belief,” in which we set out to rationally construct beliefs or examine beliefs while in fact we have already come to believe in them already. It seems that Glidden didn’t go on the birthright tour and then conclude that her feelings about Israel (and her own identity) were more complicated than she initially thought, especially with the way she wound up being drawn to the country. Instead, this is an issue she had grappled with and already subconsciously decided before she even set foot in the country. Her self-appointed guise as the “progressive American” was simply the mechanism that allowed her rational self to make the trip, even if she had been warned (and even thought herself in the past) that these trips are propaganda tools. Glidden’s narrative has all the earmarks of a conversion experience. Here the conversion is not to a religion, but rather to a frame of mind surrounding the need for communitarian experience. That desire is a basic human need, and one of the great pulls of Evangelical Christianity (as an example of a belief system that encourages rapid conversion) is the opportunity to instantly become part of a community and feel connected. Even for a non-religious Jew, the idea of an entire state welcoming them “home” with open arms, instantly accepting them because they are already part of the fold due to birth (or prior conversion to the faith), has to be an equally enticing lure.”

I go on to say: “What led to this heightened desire to feel a part of something larger than herself? At the risk of further psychoanalyzing the text (as opposed to the author; I have no idea what form her current belief system takes) too much, Glidden once again provides clues. She speaks of her disgust for living in the U.S.A. under George W. Bush and flirting with being an ex-pat in Barcelona, an indication that her nationalist identity is very much in flux. That experience didn’t work out, in part because she didn’t find herself part of a community just because she left one. Glidden talks about being a restless world traveler, seeking out new experiences and cultures but constantly feeling like an outsider. Being on a trip where one’s hosts explicitly welcome them “home” must be a tremendously powerful experience, especially when it is tethered to several thousand years of ethnic and religious tradition. The most important part of a conversion experience narration is that by its very nature, it must be told; hence, the comic itself.”

One more note related to the conversion experience: “She finds the group’s stay at a Bedouin encampment to be enraging, yet she’s successfully rebuffed again and again by statements like “you don’t have to agree with everything” and “it’s complicated.” The scene where she breaks down after hearing a woman play to her emotions in her passionate retelling of Israel’s “War of Independence” story is the classic conversion experience “dark night of the soul,” where one’s sense of doubt inhibits one’s journey through conversion and comes out the other side into a new steady state, where cognitive dissonance has faded at last.”

This is why she depicts her “younger” self as being judgmental and short-sighted…it’s a classic conversion narrative strategy to impugn one’s own old identity/beliefs in an overblown manner.

That sounds like you masturbating yourself over your hatred of a genre you don’t quite understand the point of.

What do you think about the book exactly ?

I see comments about how this or that panel is colored, and why you don’t like it.

But not much else.

This reads to me like a long hating blog-comment more than a professional book review.

“more than a professional book review.”

FWIW, nobody here is getting paid.

Glidden isn’t covering Israel for the AP; she’s recounting the idealistic young political traveller/tourist’s experince, and Israel is simply the setting.

This is a classic narrative structure. The traveller embarks full of piss and vinegar and conviction, torn between maintaining a veneer of inoffensiveness and attempting to re-educate those around her. At the start of the trip she thinks she is at an advanced stage of personal political and intellectual development. By the trip’s conclusion she’s realized that she’s barely begun to assemble the pieces of a servicable framework for understanding Israel and the Palestinian territories in particular, much less the world in general.

Glidden the character has a consciously assembled list of beliefs to be reinforced or demolished on the trip, but also an unconscious itenerary of anticipated psychological experiences. She expects to be moved by Yad Vashem, for example, and not to be moved by the Western Wall. She pre-plans her outrage at crass cultural appropriations. She regards herself as a sophisticated, modern, moral person who should have a certain set of sophisticated, modern, moral emotial responses to stimulii she already knows will be designed to manipulate her; like so many travellers, she’s later surprised and frustrated by some of her own gut reactions.

For better and for worse, for many young Americans it is a psychological and intellectual rite of passage to progress through the following stages. (A) Become interested in the Israeli/Palestinian “situation.” (B) Become obsessively interested in and fired up about that situation. (C) After what feels like exhaustive (but is actually superficial) study, develop with feels like a nuanced (but is actually an absurdly dichotomistic) position on the situation. (D) Annoy the living hell out of friends and family with deadly earnest talk and/or activism in support of your position. (E) Visit the region in question. (F) Either accept and rejoice in only affirmations of the position you held before your trip, or take Glidden’s route of wrestling with reality.

This book rings true because of its narrator’s naivete, frustration, alternating sophistication and shallowness, alternating ephiphanies and feelings of being hopelessly mired, and youthful attempts to manage her own growth. The book does not pretend to be a treatise on modern Israel or an instruction manual on dignified emotional comportment for tourists. It’s the chronicle of a young idealist trying to use the tools she has to wrangle an unmanagable volume of intersecting historical and moral considerations, and the start of her attempts to forge more mature tools.

To see this book as attempted journalism or a celebration of emotional theatre is to miss the point by a mile.

Peter: It *is* a “long hating blog comment”. You think this comic deserves better? It’s also a long consumer warning. Any HU readers foolish enough to buy and read this book after this have only themselves to blame. But perhaps you’ve already bought it and read it? No wonder you’re disgruntled.

“What do you think about the book exactly?”

Some words from the beginning and end of the blog entry: “insipid” “rotting carcass”. Clear enough?

“It’s also a long consumer warning.”

You’ve written some poisonous stuff over the years, but in casting yourself as a consumer watchdog, you have tipped over into the psychotic.

I think there was a bit of sarcasm.

Well, the consumer warning worked for me, thanks! Given the state of the alternative “graphic novel” these days, I’d say we could use a whole lot more of this kind of vitriolic reviews.

Writing a review and putting it up for debate is one thing. Hanging around in the comments and gleefully quoting your own words as further discouragement to buyers is mean spirited and undignified in the extreme.

That’s not how the game should be played.

It’s debate, Eddie.

Eddie, do you like the book?

Now I’m worried that was too confrontational.

I realize you may not have read it. But if you did…Suat raised a bunch of points in his review that I thought were worth thinking about — particularly about the ethics of travel and the appropriation of grief as a commodity. If you had a different take on those issues in the context of this book, I’d be interested in hearing them.

I’d read a library copy of How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less a few months back. It made very little impression, one way or the other, but Suat’s “frankly insipid” is a fair enough assessment.

Can’t help but be reminded of Thomas Pynchon’s finding fault with tourism because it encourages a shallow experience of other countries; a quick look at strange clothing, buildings, customs and foods, without going into a deeper understanding of the meaning and purpose behind all that.

Here, Glidden attempts to take a deeper look, but her own limitations ensure that, as Suat put it, only “trifling insights” result.

Which, ironically, means those of a similar mindset would find her book much more appealing. Far more palatable than the harsh complexity, tangled historic background, emotionally powerful incidents of brutality, richly realized persons in Sacco’s books covering that bit of geography.

It’s not just youthful naiveté and circumscribed perceptiveness to blame; that How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less is far more part of the autobiographical, rather than journalistic, genre of comics makes it “me centered” in its approach. The Pekaresque “plain narration” autobio tactic works against deeper insights. Of course her “how can a progressive be ‘anti’ anything?” conversation takes precedence over the entire village Glidden & co. are overlooking. Because she was involved in that bit of dialogue, while the village may as well be a painted backdrop.

Sacco jabbed at this “me centeredness” with his story (How I Loved the War)about how a tooth he’d chipped took on as much importance in his own mind as the buildup to the Gulf War…

I just wanted to add, since I didn’t say it earlier, that Rob’s comment on the fulcrum upon which the book turns (i.e. the “conversion experience”) holds water.

Indeed it does!

With apologies to Steinberg; a quick n’ sloppy visual analogy:

http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/mecenteredcomics.jpg

I enjoy checking out Jen Sorensen’s “Slowpoke” cartoons on her site ( http://www.slowpokecomics.com/index.html ).

There, I just found “Jen’s graphic travelogue that recently appeared in The Oregonian.” An interesting comparison: http://www.oregonlive.com/travel/index.ssf/2011/02/on_the_prowl_for_snow_ghosts_i.html .

A.E.F., sorry your comment got trapped in the filter. I don’t know why it does that…it might help to create an account (scroll down to the bottom right to find the sign in.)