Others have already pointed out that The Wire isn’t as realistic as it seems. Jimmy McNulty (Dominic West), for instance, is the hero of the American Monomyth. Here’s how the latter is summarized in the link above:

A community in a harmonious paradise is threatened by evil; normal institutions fail to contend with this threat; a selfless superhero emerges to renounce temptations and carry out the redemptive task; aided by fate, his decisive victory restores the community to its paradisiacal condition; the superhero then recedes into obscurity.

The Wire revises the myth thus: a community in hell (Bubbles – Andre Royo: “it’s a thin line between heaven and here.”) is threatened by some of hell’s inhabitants; normal institutions, paralyzed by red tape, political agendas, and business as usual, fail to contend with this threat; a self-aggrandizing supercop emerges to be afflicted by temptations and fails to carry out the redemptive task; bumping his head against the system the supercop recedes into obscurity.

That’s quite good. It revises the myth until it lies there, almost unrecognizable. Here’s my version though: in its mythology of being the only possible system (in the best of all possible worlds as Pangloss would say; at the end of history as Fukuyama would add), and in its sanctification of profit (the market will provide), global capitalism transferred labor to developing countries where the wages are low (Walden Bello):

The extreme international mobility of corporate capital coupled with the largely self-imposed national limits on labor organizing by the Northern labor unions (except when this served Washington’s Cold War political objectives) was a deadly formula that brought organized labor to its knees as corporate capital, virtually unopposed, transferred manufacturing jobs from the North to cheap-labor sites in the Third World.

Under these conditions a parallel economy thrives (mimicking the mainstream economy with its power struggles, cut-throat wars and iron clad hierarchies); those who are unprepared and uneducated, the poor, have no other option than to go underground; everything becomes simulacra in order to keep up appearances.

Hostage to the worlds of finance and economics politics is reduced to being a sport (I love the scene in which Carcetti campaigns in an elderly home: we can hear the crickets chirping because the seniors in there couldn’t care less for this kind of sport); the police are a political tool; the education system is a dead end (and the students know it – Howard “Bunny” Colvin – Robert Wisdom: “I mean, they’re not fools these kids. […] [T]hey see right through us.”). That’s why Marcia Donnelly (Tootsie Duvall), the Assistant Principal of Edward J. Tilghman Middle School says to Bubbles that Sherrod (Rashad Orange) is going to be “socially promoted” after missing school for three years. In the end, everybody knows that it doesn’t matter (those who do matter aren’t in that kind of school). Everybody has some reason to pretend that it does though. I’ll give the last word to David Simon:

Baltimore’s dying port unions, is a meditation on the death of work and the betrayal of the American working class, it is a deliberate argument that unencumbered capitalism is not a substitute for social policy, that on its own, without a social compact, raw capitalism is destined to serve the few at the expense of the many.

My problem with this statement is that David Simon should be saying it about the series as a whole. Why just season two? I hope that there isn’t a hint somewhere suggesting that, given the chance, black people would still prefer the world of the corners instead of being part of the mainstream economy.

Another instance where the creators of the series juggle dangerously with cliché is in season four (my favorite, pardon the personal note). The aforementioned season includes a kind of Teacher Movie. It’s true that, again, the writers do a good job of transcending the pernicious genre (the teacher, Roland “Mr. Prezbo” Pryzbylewski – Jim True-Frost – doesn’t win the trust of his most difficult students completely alone). But he also conveys what I call the flawed Sesame Street Syndrome (or SSS). That is, students can learn while playing. In the link above, the reporter, Nicholas Buglione, wrote:

Dr. Robert Helfenbein, an education professor at Indiana University who specializes in urban education issues, believes these films trivialize the learning process and present an erroneously simple solution to what’s really a far more complex problem: Closing the achievement gap in inner-city schools.

That goal can’t be achieved by any superhero teacher or caped crusader. It can only be achieved by closing the parallel gap between the wealthy and the poor.

The image above shows Bubbles pushing his peripatetic business. The original is a print on a t-shirt. I chose it because it is semiotically fascinating. On one end it’s the perfect symbol of the parallel economy I talked about above. On the other end it shows the absolute base of the social pyramid, the junkie that is everybody’s victim (I’m aware that Bubbles is a fictional character, mind). And yet… it’s in a t-shirt… for sale! Grammar mistakes and all!… Capitalism appropriates everything by selling everything.

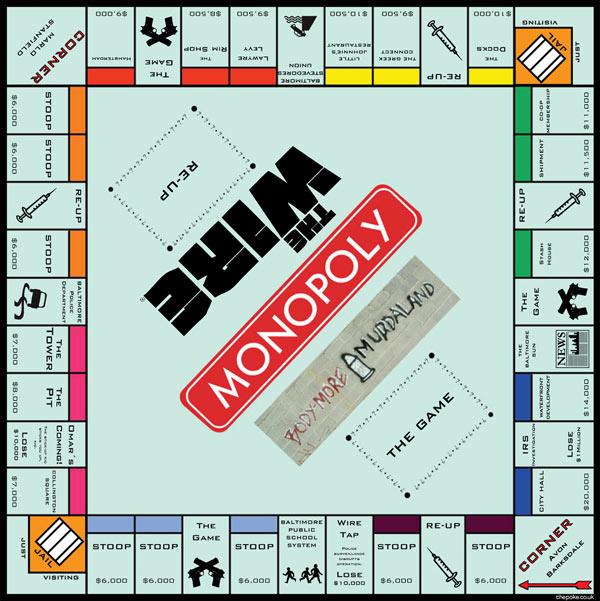

What’s missing above is the real one.

In conclusion, the use of parallel montage gives the impression of a kaleidoscopic and complex view of the city. That’s not untrue, but it just gives us the street level (in today’s world of virtual politics, even the temples of infotainment and city hall are at street level). What really affects these people’s lives is happening elsewhere.

I actually thought there were some problems with Prez’s teaching career. His whole problem with being a policeman was that he had a serious problem controlling his temper; he blinded a 14 year old, hit his commanding officer, and shot a fellow policeman. Then, he goes to become a teacher and his problem is that he’s too mild-mannered and not a stern enough disciplinarian.

It just seemed like his former personality didn’t fit the teacher movie they had going. So they changed it.

Domingos,

Good piece. For what it’s worth, I know I’ve read Simon making the capitalism argument about the series as a whole, and I’ve very clearly read him apply across racial barriers. If I can dig out the quotes, I will…

Noah,

I disagree. Prez’s arc is not just about temper, and I think they play him out very well over a measured space. I have to run out the door right now, but I’ll be back later today, and this is my placeholder declaration of my intention to deliver my Unified Theory of Pryzbylewski. Watch for it.

Yeah, there’s no shortage of quotes where Simon describes the entire series as a criticism of unregulated capitalism, like this Salon interview:

“Thematically, it’s about the very simple idea that, in this Postmodern world of ours, human beings—all of us—are worth less. We’re worth less every day, despite the fact that some of us are achieving more and more. It’s the triumph of capitalism. […] Whether you’re a corner boy in West Baltimore, or a cop who knows his beat, or an Eastern European brought here for sex, your life is worth less. It’s the triumph of capitalism over human value.”

The insinuation that Simon even hints that blacks would prefer the world of the corners is belied by, you know, pretty much every moment in the series. Poot seems a lot happier at the shoe store.

I’m also curious why you say that McNulty is a hero of the American monomyth even as you show that he undermines or deviates from virtually every aspect of it (other than the failed institutions). It’s one thing to say that The Wire dismantles that myth of the loner hero, quite another to suggest that this makes it less realistic.

As for Prez, I agree that his story isn’t about temper. It’s mostly about mentoring. He’s been trained to shoot first and ask questions later; he initially thinks that being a police is about going in guns blazing, a mode of violent authoritarianism the series would later brand “the Western district way.” But he’s a terrible beat cop who should never be issued a gun; he doesn’t come into his own until Daniels and Freamon find a better use for his talents. After Prez has learned all he can from them, the writers take him out of the major crimes unit and drop him into Tilghman Middle, a nice reversal that puts him in the spot of the mentor while he’s trying to learn the ropes of a new profession. And it’s not surprising that, having spent the last three years learning under Lester, he would be too mild-mannered. I had a few (very minor) problems with the school arc, the mysterious absence of any really awful teachers foremost among them, but I didn’t miss Prez’s itchy trigger finger.

Yeah, I’m still not convinced. Prez’s problem was a lack of mentoring…but he remains prone to anger. He deals poorly with stress. It’s why he shouldn’t have been a cop — I don’t think he would have been a good teacher either.

Noah: re. Prez, I agree, he would have been eaten alive, but most importantly, schools are part of the community; the community’s problems are the school’s problems. No individual has the power to change anything.

Thanks Jason!

Thanks Marc for your great Simon quote. I was almost certain that the hint I talked about didn’t exist. That part of my post is poorly researched. My excuse is that I wasted too much time watching season four while the deadline approached.

McNulty is an American monomyth hero. It seems to me that the authors started with some structures frequently used in the entertainment industry (they didn’t want to be Home Box Office poison) subverting and transcending the genres that they used.

Pryzbylewski: not about temper, not about mentoring. Anger plays into it, but not in the heat-of-the-moment uncontrollable way. It’s a deeper anger, an anger of resentment and insecurity. Prez in his early days is not acting out of raw temper, or assuming a learned mode of behavior; he is lashing out from a volatile mixture of fragile ego and stark fear. In short, Prez is Ziggy.

If Ziggy’s family connection had been to police rather than stevedores, he’d have shot up his patrol car, put a slug in the wall of his unit’s office, and he damn sure would have clocked a project kid in the eye with the butt of his gun. But Ziggy wasn’t a creature of temper. Ziggy was desperate for respect in the only milieu he knew to look for it. Ziggy was terrified of being proved a failure, a fuckup, a geek, and so he formed a thick layer of humor, bravado, and rage.

A cop acquaintance of mine once said this to me about his profession, and I take it to be true. He said, “About a third of the guys out here, they’re like me. They just want to help people. All the rest of them are the kid that got picked on at school and now he’s got a gun.” When Prez takes that kid’s eye out in the projects in Season One, he’s not doing it because the kid pissed him off. He’s doing it out of anger at the world, and to prove to the world and to himself that HE’S in control now.

It’s only later, after Lester has shown him how he can be competent and respected through the wiretap, that Prez is then confronted by the kid he hurt, and he realizes that he was not in control at all.

And that isn’t the end of his journey, because while Prez finds a new well of confidence and self-respect in his work with Lester, he’s still a cop, and he still carries a gun, and he has not recognized his own flaws sufficiently to make him safe with that responsibility. And so his renewed confidence leads to overconfidence, and in the chase with McNulty, some part of him (subconscious, surely) sees an opportunity to finally achieve that original goal of respect through “manly” police work. That it goes so horribly wrong is Prez’s second wake-up call, the one that finishes the job that the kid with the eyepatch started of shocking Prez into self-awareness. At that point, Prez knows he shouldn’t have been a police, with the power of life and death.

Prez is driven to teaching primarily out of his guilt over the kid from the first season (though there is also an element of him needing to have a career that feeds his ego’s need to be in control. Cops and teachers both wield big swinging dicks, even, or maybe especially, the good ones. And Prez, like all the major characters on the show, is complex. Nothing he does has only ONE motivation).

The Prez that shows up in that classroom, though, has had two huge blows to his sense of self that have resulted in him making an absolute resolution to himself to never let something like the blinding of the kid or the shooting of the cop happen again. Prez’s arc as a teacher is not a wimp learning to be a disciplinarian. It’s someone who has seen what can happen when he lashes out getting over his fear of ever doing so again and learning how to instead exert force (either verbally or physically) in a safe, mature manner. When he disciplines the snatchpops kid in the last episode, it’s through a controlled hand on the shoulder and a stern and unwavering voice of authority.

All of the preceding is why Pryzbylewski’s character arc is my absolute favorite from the show, and why I could not let stand the dismissal of his intense personal growth as mere plothammer.

Jason, I really like that description of Prez. I just didn’t see that in the actual show though. That is, I didn’t see the show link his changes to his earlier experiences in the way you’re describing.

But…mileage differs, obviously.

For me it’s all in the way he looks at the kid who walks by while he’s talking to Freamon on the bench at the end of Season 3, and it’s resonance to the look on his face in Season 1 when he realizes who the kid in the eyepatch is. It’s subtle. But I think it’s undeniably intentional.

That’s a thoughtful, persuasive flowchart of Prez’s motivations, Jason. But I still can’t fully believe in the redemptive power of Prez’s new self-awareness. His need for control–and self-control–will still be thwarted by the gritty reality of the public schools. In my inner city high-school classroom I had to be foster parent, social worker, cop-on-the-beat, mentor, Socratic interlocutor, referee, disciplinarian, diplomat, stage manager and standup comedian all at the SAME TIME to maintain any control at all over my restless audience of thirty, a third of whom were talking out of turn or texting surreptitiously, a third falling asleep, and a third having a bitchin’ sexual fantasy. Days of good-natured, exploratory banter as seen in Prez’s classroom were few and far between. I don’t think I was an unresourceful or cynically detached teacher, but unless I picked my fights very carefully, it felt more like that scene at the towers late at night when Prez did lose control, with bottles, TVs, and air-conditioners raining down. My stress was frequently off the scale. Subject matter? What subject matter? Well, maybe on a good day…

And then you still lose Dukie to the dark corners of the Arab camp.

Nah. If Prez hadn’t blighted his record as a street cop and gone on to the rank of detective, there he would have found his calling. Remember how he raved excitedly to Valchek about following the bread crumbs to Stringer’s money? That’s real control, not puppetry.

I agree with you that Prez is arguably the most compelling of the wire’s flawed charatters. I just think–and this occurs to me just now–that he’s finally unknowable.

Does it make a difference to your valuation to remember that Prez isn’t teaching high school? Even in my white bread middle class public school, there was a huge shift in demeanor of students from middle school to high school, and the show goes to great lengths to show that Prez is teaching at essentially the point of no return — the last chance to reach a lot of the kids, or to interact with them as kids or at least in transition instead of as full blown young adults.

I think it’s also worth noting that Prez’s first year is a disaster. He’s only saved by the fact that Bunny’s Corner Kids program takes some of the worst behaved kids out of his class. But the fact remains that he isn’t able to really teach them anything other than dice statistics (which isn’t NOTHING, but is more of a survival technique by Prez than an actual learning opportunity), the standardized tests ruin even that glimmer of hope and also end in mass failure, there’s a stabbing in his class, and though he learns enough to deal with the majority of a class as a class, he’s seen very clearly losing all of the “main” kids that the story follows. Randy, Dukie, Michael — even Namon would have been gone if it was just Prez’s story. By the end of the fifth season, Prez knows what he’s doing. By the end of the fourth season, he’s yet again realized that he doesn’t.

I’ll also admit to, when it comes to The Wire, giving up at least a little bit of my own critical autonomy to the fact that Simon and Burns and their crew of writers have shown time and time again how well they’ve researched and how well they know their subject matter. Ed Burns was a cop and then a teacher, and because the show for the most part has put forth an honest (if fictionalized and occasionally neatened) view of whatever they decide to focus on, I give them a wider berth than I would anyone else. This might be a mistake, but it’s one I have a hard time avoiding if it is.

True. That’s a huge difference of age, street wisdom, and, especially, sexual maturity. Some middle-school girls are already worldly women; while many of the boys, despite their bravado, are still tender kids. Contrast Zenobia’s sass with Dukie’s gentleness.

My two years teaching 7th and 8th grades were in a private, not a public school, so my perception is skewed by the socioeconomic contrast between my middle- and high-school experiences as well. Ed Burns, we know, had this to say about that: “Education is our biggest failure as a society. The inequality in our system disadvantages millions of people. It borders on the criminal.”

Bodie spoke for Prez’s class?-and for America’s entire underclass?-when he said “This game is rigged, man.”

I actually didn’t think the show did a whole lot in terms of showing Prez’s evolution as a first year teacher. It seemed clear that each specific instance of Prez’s teaching was meant to (and, as a former urban middle school teacher, I say rightly so) conform to a central truism of ghetto pedagogy: the first year is about survival, not the kids (a line echoed by one of his colleagues). That being said, I loved how the creators also skillfully showed the variety of the teachers in the school. There was the enthusiastic teacher who had all her kids involved in the learning process as well as the rigid disciplinarian male teacher who spent his 15 seconds of screen time assailing his class as lazy and apathetic. These archetypes hold true in the schools I’ve taught in. But Prez’s personal development as an educator seems like less of a compelling subject to debate, since to me, it seemed his year in the classroom displayed the challenge of learning how to adapt to an incredibly difficult system more than anything else.

I just watched _Inside Job_ and, I mean, wow!…