Long-time and frequent readers of HU will recognize the ongoing friendly disagreement I have with Matthias Wivel about the degree to which literary things — literary theory and its literary lessons, literary experimentation and its literary insights — are important for comics. I almost said for “literary” comics, but that of course would have begged Matthias’ question, which is in part why comics need to be literary at all.

Toward the end of the lengthy theoretical discussion that erupted in the comments section to his remarkably rich interview with Eddie Campbell (much of which we unjustly ignored in the comments!), Matthias wrote:

I don’t dislike Krauss; in fact I think some of her work is pretty great, but yes, I have at times found her unneccessarily laborious, caught up in linguistic issues that may have been relevant at the time, but now just get in the way of her otherwise good observations.

Is there a way of applying her method to less obviously linguistic insights in visual art? Probably, but my point all along has been: why is that so important?

Caro, you have a real preference for whatever theoretical insights any given work of art may give you, and I am not at all opposed to that — I find that stuff as fascinating as the next man, BUT there are so many other equally valid and compelling ways of experiencing and talking about art, ways that you can frame in exact theoretical terms, but which to my mind don’t necessarily benefit from it.

Art isn’t theory.

In the question about the importance of literary methods and insights to comics (I’ll limit myself here to the discussion of comics, rather than art in general, which Krauss herself has addressed quite often!), there’s more at stake than theoretical answers to ontological/epistemological questions, as interesting as they are. There are practical issues of the artistic scope that comics can and has engaged with as well — and scope not only has implications for understanding — and imagining — the potential of the art form but also for appealing to broad audiences with diverse artistic tastes. I wrote a lengthy response to Matthias about the importance of engagement between comics and literature/literary theory, and Noah asked me to move it from a comment to a post. So here it is (with only minor edits from the comment version).

Matthias, I remember that you’ve made this same basic argument before with regards to literature itself — in the same way that art isn’t theory, comics aren’t literature, and so on and so forth. It’s a sort of medium-specificity that insists on boundaries — and while I GET it, I think those boundaries may be more limiting than they are valuable, for any purposes other than pedagogical.

For my own purposes, as you say, there’s certainly an aesthetic preference at work here — but there’s also an aesthetic agenda for those boundaries to become more permeable. Not permeable so that there’s no possibility of ever deploying the distinction to good effect, but permeable so that there’s more possibility of deploying the mixture to good effect.

It’s partly, as I think we’ve discussed, the fact that theory isn’t a “way of experiencing and talking about art” it’s a way of experiencing and talking about the world — one to which visual art has yet to make its fully evolved contribution. I believe that’s a contribution that needs to be made, considering the impact and reach of theoretical vantage points not only for “talking about art” but also for talking about all kinds of other things, including politics, and identity, and the politics of identity. If the vantage point of art is insufficiently represented there, that is an exclusion — even if it is one that’s largely self-inflicted. Participating in that conversation should in no way prevent all the other ways from experiencing and thinking about art from continuing on apace, as not everybody will be inspired by theory in the same way that not everybody is inspired by aesthetics. Surely there’s room for all of the above?

But it’s also that such an engagement with language/linguistics/literature in particular is more important for comics and important in a different way than it is for visual art. It becomes, to me, a question of broadening the field of comics sub-genres — in English-language comics, at least, currently there are a) a couple of unique genres, the fully visual-narrative and visual-metaphorical ones; b) the comics versions of genre fiction, SF, romance and heroic stories; c) plenty of autobiography and memoir; d) biography; e) journalism; f) children’s stories. Then, there are those few cases that qualify as literary short stories (although those trend toward the visual-narrative and visual-metaphorical genres, for various reasons many of which, I think, are subcultural). There are also a handful of experimental comics (which, as you know, I’m extremely fond of, but that is a very new and nascent genre.)

But there’s very little in comics that’s comparable to — let’s call it “Booker fiction,” the kind of fiction that gets nominated for and wins the Booker prize. (Although Booker books are not really homogeneous and my bias against current American letters is showing; “Pulitzer fiction” just suggests a somewhat different scope and approach to me.) Booker fiction is very engaged with theory — not just contemporary theory but traditional poetics. It also tends to care deeply about literary aesthetics and a range of pleasures that come from prose.

You’ll probably come back with the argument — as you have before — that Booker fiction is a literary genre and that comics doesn’t need to model itself on something so outside. But the question “why shouldn’t it take that genre as a model?” is equally valid. There’s no consistent argument that Booker fiction shouldn’t serve as a model for comics — unless comics is also going to reject all the other literary genres right along with it: popular genre fiction, the literary short story, biography, memoir…

I find the possibility of comics engagement with fiction at the Booker level especially compelling considering that Booker fiction’s engagement with theory and form — both questions and the mechanisms for getting at those questions — is at a point where it needs fertile new terrain, and “the illustrated book” is extraordinarily fertile. Books like Fate of the Artist point in that direction for me, and I think it’s tremendously inspiring. It’s a different direction from the one folks like Warren Craghead and Jason Overby are exploring, and — as marginal as experimental comics is — truly ambitious, truly literary comics are vastly more rare.

At this point, though, I generally have the sense that there are several pressures working against comics producing a work that’s really truly comparable in scope and ambition to a Booker novel. The biggest obstacle is auteurism and the DIY insistence on self-expression, which lead people who don’t have a lot of literary background to resist collaborations drawing on varied expertise (the kind of fecund collaboration, for example, that Anke F. has with Katrin de Vries). Hipster ennui — that classic mix of self-importance with complete and utter lack of seriousness — saturates art comics culture and generates a contempt for complexity and intensity that works against any meaningful engagement with literature. (The hipster problem also severely damages American prose letters and is to some extent at fault in the problem Elif Batuman identified in the LRoB essay we talked about here.) Hipster-fic generally ends up being either irony or what Mike called “me-comics”.

But I also don’t think we should discount the role of disciplinary distinctions here. Art education plays into this as I’ve mentioned before: because English is more valued at the middle and high school level than art, literary people often have much less drawing training than art people have in writing. But this can also lead to a lack of understanding among art people about the differences in the way a trained literary reader will approach, say “The Fortress of Solitude” from the way that same reader will approach “Midnight’s Children”, or the fiction of, say, Umberto Eco. It’s a failure of American education that we don’t equip our students to read those books the way they’re meant to be read before the time when students have to specialize, so that those reading protocols are such specialized protocols. But it nonetheless remains true that those books do demand reading protocols that only highly trained readers have — most people writing comics and writing about comics, even the best writers in comics, aren’t highly trained readers. There are precious few people in art comics who are palpably sophisticated readers by the standards of fiction readers — because a lot of those protocols just aren’t mastered, if they’re even taught, until graduate-level study in literature.

Similarly, the academic art world sometimes seems hermetically sealed: unlike literature departments which (at the graduate level) embraced their “cultural studies” sister departments to the point that traditional literature almost vanished entirely, the “department of art” is very separate — methodologically and institutionally — from departments of visual culture (which tend to be, really, part of that greater diaspora of literature).

But this separation of the disciplines becomes a problem for comics which draws on the media and discourses specific to both. One response has been to claim comics exceptionalism — the only discipline you need to know anything about is comics themselves. But that’s obviously bullshit: comics scholars tend to know art or they tend to know literature, and each enriches their insights in different ways. This is why I brought up Noah’s oft-expressed annoyance at the banal content of many comics: it’s just exasperating to hear people make “literary” claims for a book like Asterios Polyp. It’s a perfectly good pedagogical tool and an interesting experiment in visual device, but by even the middlin’ standards applied to literature, it’s pretty run-of-the-mill as fiction. It’s equally exasperating to read comics criticism that examines a really pedestrian, obvious narrative, something that’s probably intended for diversion and fun, in lofty formalist, new critical terms — the type of review that explicates literary devices which are completely on the surface of the work. It’s like someone writing a piece of student criticism about a student essay. This doesn’t happen nearly as often in professional and semi-professional reviews of prose books. The expectation is that people who read Bookforum understand literature and there’s no need to spell out, or often even point out, the formal devices at work in a book. (And of course, here I’m talking about the semi-professional comics critics, not random people writing about books they love or hate on their personal blogs.)

A great deal of the writing in (and about) comics is — at its absolute best — BFA-level writing. And I’m not talking about prose-craft — I’m talking about the sophistication of the engagement with ideas.

So when claims are made about comics-as-literature, the impression is often that comics people don’t know very much about literature, let alone theory. But the bias against theory seems to be part and parcel of this dual belief that literature and literary structure basically work the same way that art does but just in a different medium, and that what you learned in college is all there is to know about literature. That’s a misperception due almost entirely to these overly-strict boundaries. I do think it’s extremely important for comics that those walls come down.

It’s all been straight downhill into the moshpit since Classics Illustrated.

It’s TCJ’s messboard again!…

Yeah, we suck.

I don’t mean that facetiously. We really do. If anything, I think you’re giving us too much credit. For example, I don’t think comics exceptionalism is a response to the wall between literary and art studies. I think it’s the result of comics critics, almost without exception, writing from a perspective that’s rooted in fandom. There’s not much interest in writing about anything that isn’t or can’t be easily assimilated into subcultural thinking. I believe that’s why there’s all this emphasis on history and visual technique. This may also be why when you see a comics critic write about, I don’t know, James Ensor or Chris Marker or Thomas Pynchon, it has to be related back to comics in some way.

I’m not excepting myself from your complaints. I’m certainly guilty of writing “the type of review that explicates literary devices which are completely on the surface of the work.” There are times when I can justify it in terms of setting the stage for discussion for the more complex devices at play, but a lot of times it’s just a bad habit–writing something for the sake of writing anything. It’s a pitfall of trying to write pieces of a certain length about material that just doesn’t warrant it.

By the way, to the extent that most comics critics are familiar with any outside medium, that medium is film. The serious study of literature and/or fine art is, I’m afraid, a little too demanding for our cohort.

Quoting Roland Barthes, going back to the whole possibility of illustrating anything:

“Nor are linguists the only ones to be suspicious of the linguistic nature of the image; general opinion too has a vague conception of the image as an area of resistance to meaning- this in the name of a certain mythical idea of Life: the image is re-presentationwhich is to say ultimately resurrection, and, as we know, the intelligible is reputed antipathetic to lived experience… All images are polysemous; they imply, underlying their signifiers, a “floating chain” of signifieds, the reader able to choose some and ignore others.”

Giving in to the temptation to endless repetition that is certainly rooted in my death drive, I already posted this in the comments of the Wallace Stevens discussion, which has pretty much fizzled. But I think it works for this post.

Also okay Booker, but– what about the Turner Prize?

And should we be discussing why the literary fiction industry is an ideal model? There was that Paul Auster graphic novel, which I found underwhelming.

And… how is thinking that literature and art work somewhat similarly (which I am okay with, frankly) equal “overly-strict boundaries?” I may have missed a step in your logic, but that does seem a tad aporetic.

Caro, I think you’ve misunderstood my point: I have never argued that comics aren’t literature or that they can’t or shouldn’t aspire to learn from it or be it. Not at all.

What I’ve been arguing against is the somewhat exclusive premium you seem to place on theoretical engagement in art, whether comics, literature, or whatever. It’s all well and good to demand that kids should be taught to read “Midnight’s Children” in school — I can’t disagree with your point that literary education generally is lacking, and think it’s even worse for visual art.

However, your formulation begs the question of whether there’s a *wrong* way to read such novels. The fact remains that a lot of people don’t read at the level you ask for, and I don’t necessarily think that’s bad. Why is it the preferable way to read? This issue came up at one point when we were discussing Austen and Dickens — you pointed out interesting, underlying literary aspects of their work — e.g. “Northhanger Abbey” parodying the gothic novel — while I maintained that the reason why they are well-regarded are much more accessible, having to do with their characterization, description and plotting.

My further problem is with critical or theoretical approaches to comics, or visual art, that privilege the ‘literary’ or ‘linguistic’ and depreciate the visual. This was my issue with the “Asterios Polyp” discussion. It’s far from my favorite comic and I agree to an extent with some of the criticism of it put forward during our roundtable, but I found a lot of it to ignore the originality and beauty of its visual realization. In strict literary terms, the characterization of Asterios, for example, is pedestrian, but the images enrich it considerably.

And while I agree with Robert that we suck to an extent, a lot of that suckitude has to do with the inability of most comics criticism to engage the work not only on a theoretical or literary level, but a visual one. You’re right that the visual is prioritized highly by cartoonists and in fan culture, but critics and scholars seem to me even more ill-equipped to talk about it than they are when it comes to the more linguistic aspects. This again has a lot to do with the problems you describe in the educational system, a system that privileges the linguistic over the visual.

I don’t understand this separation of the visual and the linguistic. When I appreciate images I always remember the example of the pompier artists. Beautiful images for the sake of beauty are just eye candy to me.

The meaning is what matters. If the meaning is flawed (escapism, childishness or whatever…) while the images are beautiful something is wrong with the latter.

That’s mainly why I don’t like Moebius and his ilk.

Bert and Matthias both come from the visual art world in some sense, so it’s interesting that their objections are in some ways opposite. Bert is with Roland Barthes, arguing that art can basically be read as literature — that both are understandable through post-structuralist theory as floating chains of signifiers. Matthias on the other hand argues that there are aesthetics outside theory…which not coincidentally also implies that there is visual art outside language.

If I understand Caro aright, she’s with Matthias on the technicality, but more with Bert in spirit. That is, she believes that there should be a separation between visual art and language — but believes that that separation needs both to be theorized and to contribute to theory.

I’m honestly still trying to figure out exactly what I think about all this. Here’s some half-formed thoughts:

— contra Matthias, I don’t think that there’s anyway that the art can save the banality of the story in Asterios Polyp. I do like the art in that book…but it’s deployed in a really simplistic way to tell a banal story. So…I guess the point is that I don’t believe that technical skill, or design skill, is a substitute for theory. In that sense, art *can’t be* outside theory, or at least is not a sufficient answer to theory. You *can* enjoy Asterios Polyp as a series of pretty pictures; I did myself. And you can take the theoretical position, I suppose, that pretty pictures are more important than anything else. *But*, if you are like Caro and are looking for theoretical complexity in your art, then Asterios Polyp really has very, very little to offer. Because it’s a stupid book. And pretty art is not in itself a thoughtful theoretical statement.

So— I’m willing to grant that pretty art is worthwhile in itself; I like eye candy. But I’m not willing to grant that pretty art in itself offers a real challenge or alternative to theoretical complexity. And you sometimes seem to suggest that it does, Matthias — and I just can’t follow you there.

—contra Caro, (and with Bert) I’m not a huge fan of Booker fiction, or of contemporary literary fiction in general. So the prospect of comics being more like that doesn’t really turn my crank at all. I mean, I don’t really like Dan Clowes or Eddie Campbell, who I think are the people Caro thinks about when she wishes for more literarily engaged comics artists…so I’m not sure where that leaves me exactly. I feel like literary fiction over the last 50 years or so has kind of crawled into its own navel and died. I think Caro’s right that comics might offer a way out — there’s a poetry in Hagio and Tsuge, for example, that manages to be both really ambiguous and suggestive in a way that I think might benefit literary fiction. But positing literary fiction itself as an ideal seems pretty problematic (I mean, is the writing in Bookforum really especially good?)

— contra Bert, I just don’t see visuals and language working in exactly the same way. That’s not an ideological stance I don’t think. It’s just a logical leap I can’t quite manage. Language is arbitrary; images just seem to me like they’re not as arbitrary. I don’t think that makes images more real (there’s a good argument to be made that reality is in fact arbitrary.) But I think the fissure is a potential that comics, which deals in both words and images, can exploit.

Here’s a good example of what I said above:

http://tinyurl.com/3dyzfzo

José Luis Salinas was a great Argentinian master. In his _Cisco Kid_ strip above we can’t find many flaws. And yet it is wrong in a fundamental way: the bad guys are ugly, they’re sloppy (they didn’t shave) and at least one of them reminds us of a rat’s face. In a word they’re stereotypes. That’s why I consider this comic strip flawed both as literature and visual art.

This is what James Gillray has to say about the subject:

http://tinyurl.com/4xahgb8

“Matthias on the other hand argues that there are aesthetics outside theory…which not coincidentally also implies that there is visual art outside language.”

Matthias doesn’t seem to be around so I’ll answer for him in brief.

I don’t think Matthias means that at all, not in his comment anyway. I think it’s pretty simple. He’s just reminding us that for most of the world, there are other ways of looking and understanding. In other words, that theory is just one pair of spectacles; one that is sorely lacking in comics surely but which does not undermine the need for everything else. He may even enjoy the lens of theory at times and have great sympathy with the concept of images as language. It’s an interesting way of looking at visual art which mix text and image for instance, like those of Duchamp.

You’re making an argument for “content” (a word I’m using in its generally understood meaning), and suggesting that Matthias only perceives superficialities. Which is why your first argument doesn’t work – where you’re equating this “content” with theory as a whole. Matthias is taking Brecht’s position that form is content, and what you’re saying about Asterios Polyp amounts to a disagreement as to the quality of the form. Further, wouldn’t you say that some theoretical readings tend towards an arch formalism (as Barthes himself suggests) which also have little to do with the kind of “content” you hold in high regard? Btw, is the “characterization, description and plotting” which Matthias brings up merely a superficiality you despise?

Wow, lots of comments since I went out. Cool. :)

Just a couple of quick points: I think sometimes we talk at cross purposes when this comes up, because of the perception that I think literary fiction is some kind of ideal. I don’t, actually — the ideal to me is not for any specific model to be represented but for all possible models to be represented, for comics to be equally diverse as both literature and art.

The problem for me is that the influence of the subculture, fandom, as Robert points out, combined with the fact that most cartoonists are trained in visual art schools without strong training in writing and literature, leads to there being far fewer comics modeled on literary fiction than there are comics modeled on other things. I don’t think that active cartoonists are going to read this and suddenly start modeling their work on literary fiction — it’s not a zero sum game where comics modeled after literary fiction replace comics modeled after other kinds of fiction or on any kind of visual art. I don’t want Noah’s to suddenly have even FEWER comics that he likes than are available to him now. My point (1) is just that it would be nice if literary fiction were part of the mix, more part of the mix than it is now.

IMO, Suat, the arch formalism you’re talking about tends to be more common in experimental fiction, when writers were trying to work out how to do something. Once they got the hang of it, they tended to layer back in more of the appealing aesthetic things. Charles Hatfield objected to my using the word “maturity” for this but I can’t think of a better one — to me, the separation of conceptual structure, formalism and aesthetics is a sign that someone’s tinkering, trying to figure out how to do something, and isn’t to the point of synthesizing all those things into a “mature” work.

I don’t think that it’s therefore a question of a wrong or right way to read — it’s a question of thicker or thinner readings. It’s not that I disagree with Matthias that attentiveness to the visual (or formal, etc.) elements is valuable. It’s that I agree with Noah that beauty doesn’t compensate for banality. I don’t object to beautiful banal things, but I don’t want them to be all I have to choose from. Wading through a slough of banality to find the least banal thing is tedious in the extreme and beauty doesn’t help. There is a LOT of banal prose writing that sounds nice but is really just fluff, just like there are a lot of banal comics that look nice. But there is a critical mass of prose books that are both aesthetically successful and really conceptually intelligent. So another point (2) is that there are a number of factors that make it easier in comics to ignore how much that intelligence matters — one of which is an over-emphasis on aesthetics and an underemphasis on conceptual complexity.

That said, I understand Matthias’ point about the need to engage with work on a visual level. But I don’t think it’s a bias against art that makes people not talk about the images. Some of it ties into this explication business, the sense that explicating what’s there on the surface isn’t the job of criticism. It’s harder to talk about the visuals while prioritizing things that aren’t on the surface. But some of it is also just that people who aren’t trained in art can’t talk about it as easily as people who are: I talk about literature because I have vocabulary to talk about literature at a level at which I don’t have vocabulary to talk about art (although I have a lot more vocabulary to talk about art than I did a couple of years ago when I started trying.) Maybe Matthias can help us out over on Tom Crippen’s post with talking about the visuals?

Did anyone ever have the experience as a kid of seeing faces in everything? The front of a car is obviously impossible to not anthropomorphize, but the bark of a tree, the texture of a cloud, cracks in plaster, tiles on a ceiling, all become things other than what they are, in order to be recognizable for what they are… even the face of one’s mother.

I understand that that’s fairly universal (as in, not cultural, like language), but it is a way of signifying through absence in order to make use of things outside language (i.e., exist outside of our heads). It’s a way of coming to terms with death, frankly– language lives, it comes from God, and images reflect, images return to God, which is why our image of Christ (the Word made flesh but also the singular image of God) is his corpse, aymbolized (abbreviated) by the cross. The spirit, the ghost, lives. And, as Chesterton says, “A corpse is not a man; but also a ghost is not a man.”

So I fully acknowledge (and have all along) that images don’t mean in the same way words do– but they do mean. And there are all kinds of ways in which certain uses of language and images (as in modernist formalism, or in specific comics genres) have more in common than other uses of language and/or images in other places and times.

What do you do with music? It operates performatively on a conscious level in a way that echoes speech inflection, espcially in early memories, and it also emerges from properties of objective vibration and subjective perception. Seems like you could say the same, in a less vibrant way, for language and images. The signals we find intelligible have crystallized into recognizable forms by our cultures, and also our own brains.

There is something in an image that we cannot say, and something in a word that we cannot picture. But the danger lies in imagining and projecting purity in tings which we understand– which is how the whole dustup about analogy and univocality. Everything is referring to one big blind spot, which is perpetually right behind us and can’t be captured in mirrors.

Nah, I like characterization, description and plotting fine. And I like eye candy too! I enjoy the loveliness of Asterios Polyp. And I’m certainly not saying that Matthias only likes superficialities. I strongly suspect I’m more tolerant of superficialities than he is. Caro will occasionally ding me because, overall, I prefer empty, well-rendered superficialities to more ambitious works that fall short. Better James Bond than the American any day.

In terms of theory…I think the problem is…theory really is pretty totalizing. You don’t get outside theory by saying, for example, that characterization and description and plotting are outside theory. The argument about whether you can approach aesthetic experience outside theory — whether anyone can approach any aesthetic experience outside theory — is a huge issue. Saying “Art isn’t theory” is obviously true (they’re not equivalent)…but as a polemical statement it definitely speaks to issues which are really controversial.

It’s fine to say that form is content…I’d even agree. Eye candy is content; the purpose is the prettiness. But…how do you assess whether that’s a worthwhile purpose without theory? How do you compare it with other achievements without theory? How do you decide whether it syncs up with the narrative elements without theory? What exactly is the non-theoretical position from which one is appreciating these works…and what defense of that non-theoretical position is there that hasn’t already been fairly thoroughly decimated by (for example) Marxist critics like John Berger or Terry Eagleton?

Anyway…as you suggest, I don’t think art/language maps onto form/content. There’s form and content to visuals as well. One of my problems with AP is that the art’s meaning is as mundane as the story’s; hippie poster art to show that a character is a hippie and so forth, or different shaped speech bubbles to demonstrate different personalities — it’s all really diagrammatic and boring. Since I brought Hagio up before…in Hanshin, the doubling in the narrative is reinforced and complicated by the doubling in the art, and the repetitions in the art, and the absences in the art, have thematic resonance. So you’re right that the problem with AP isn’t story bad/art good; it’s that, while both story and art have a certain surface skillfullness, they’re both (I’d argue) ultimately simplistic and banal.

I do think that the formal appeal of the art in AP (which is quite high) is much more impressive than the formal appeal of the story (despite the claims Matthias makes for the later.) On the other hand…the Disappearance of Alice Creed is something where the story’s formal elements are quite high, while the formal skill of the visuals is workmanlike but not especially impressive (the content of both writing and visuals are negligible.) And now that I think of it…I’d probably rate Alice Creed and AP at about the same level overall, though the second annoyed me more since it was more thoroughly overhyped (Alice Creed was overhyped too, just not quite as much.)

I think it’s interesting that when the aesthetic elements of literature come up here, it is generally “characterization, description and plotting” that are the elements that get referenced — rather than setting and tone, which are actually far more aesthetic and less structural elements in prose writing. I’m just sayin’…

Despite the impression I’ve been giving here of not caring about aesthetics, I’m actually HUGELY invested in setting and tone, far more than description and plot, at least. Theoretical sophistication, in the best prose writing — and also in my favorite films — actually has the effect of allowing description and plotting to recede and setting and tone to take a more prominent role, so that the more theoretical and abstract a work’s meaning is, the more dominant its aesthetic elements can become. Plotting and description require direct effort to be expended in the prose that can be avoided if a more theoretical path is taken. I think that’s what happens in many Godard films. The purely aesthetic elements can come to the fore, more immediately, because the theoretical structure stands in for plot. So for me, a theoretical approach to meaning opens up room for a more aestheticized experience rather than a less aestheticized one.

Noah: “One of my problems with AP is that the art’s meaning is as mundane as the story’s”

The art is the story too. If the story sucks, the art sucks. The dichotomy is a false one.

Caro–

You’re implicitly drawing equivalencies here that I’m really not comfortable with. It’s one thing to say that comics could use a substantial infusion of the thinking that informs Booker fiction. It’s quite another in this context to lionize Godard’s films. Novels like Atonement, Never Let Me Go, and Wolf Hall enjoy a substantial audience, and they’re accessible to a large number of people beyond that. Godard is the most notoriously inaccessible of the canonical filmmakers. I doubt there are many in the audience for art-house films who can’t handle the Booker material, but the vast majority of them look at Godard’s films after Breathless in complete bewilderment.

Theory is pretty rarefied, too, and I would never complain that an artist isn’t using it as the foundation for his or her work. The Booker material is informed by it to a degree, but I don’t think it’s foundational. In fact, when McEwan implicitly called attention at the end of Atonement to how much theory was guiding his hand, he made a lot of his readers (including me) really angry–it felt like he was throwing people’s engagement with the love story aspects of the material back in their faces. One of the few good things the film adaptation did was fix the ending so people could have it both ways. They could enjoy both the love story and the metafictional conceit that underpinned the work.

Noah: “Eye candy is content; the purpose is the prettiness.”

The purpose is not the content. The content of eye candy varies, but if eye candy is “all” there is it means that the content is shallow, not that there isn’t any content at all.

Domingos, when I say the content is the prettiness, I mean that that’s the content, not that there isn’t any content. Pure formal or aesthetic appreciation is content, I think — it’s art for art’s sake, if you will. It is shallow…but I don’t think shallowness is necessarily wrong in all instances. Like I said, I prefer it in some cases.

“The art is the story too. If the story sucks, the art sucks. The dichotomy is a false one.”

I think the art is the work of art, just as the story is. But the art isn’t the story. As Caro said to Alex, that’s a metaphor. Works of art can be analytically broken down into different components for purposes of discussion. The breakdown is somewhat arbitrary, but that doesn’t make it false.

I think if you insist on art and story being the same thing, you can miss a lot. In part because the way the different ways the art and story work together is an important way in which different comics succeed or fail (or different works of art.) I was thinking about this in terms of Funny Games — a movie which I think actually integrates the visual and story elements much more successfully than either AP or Alice Creed. The bleak moment after the son gets shot is both visually and narratively devastating; the elements converge. That’s what makes that scene so effective — and you can’t really talk about it if you insist that the art is always the story.

I don’t know…I actually appreciate your constant resistance to binaries. It’s good to be reminded of their limitations. But at least for me, I don’t find tossing them out altogether helpful.

I haven’t read Atonement, but I just wanted to note that Robert’s anger at McEwan is a *theoretically informed* anger. The belief that engagement with a love story has more value than a more theory-based approach is a position within theory, not outside it.

If the art isn’t the story Frans Masereel never told any stories. I guess that the art is other things too, but so are words.

Domingos, I think the art can be the story…at least metaphorically. But I think saying the art is the story, period, in all circumstances, limits how we can talk about comics in a way that I don’t find all that helpful.

I just looked at Asterios Polyp just to stay relevant. Yeah, I remember Dave Mazzuchelli. Orientalist-retro pretentious graphic design.

I think Caro (to join the chorus of people speaking for people) probably thinks that a few more critics should have some familiarity with theory (it’s philosophy based on art criticism, after all). It just makes culture and meta-culture a little more mysterious and trippy; I have no problem with that.

Bert spoke for me fine — I think that’s a good summation. I also think — probably more importantly — that a few more cartoonists should have some familiarity with theory.

Which gets to Robert’s point about MacEwan:

IMO, if it’s guiding his hand, it’s foundational — could he have written the book without that theoretical vantage point in his head? If the Booker WRITERS weren’t familiar with theory, then would Booker books read like they do? Probably not. It might have been more politic to avoid the direct gauntlet to readers who weren’t interested in the theory, but it’s factually inaccurate to discount the importance of theory to the very existence of the book in the first place.

I don’t mean to draw an equivalence between MacEwan and Godard, though. The Godard is absolutely an extreme example meant only to illustrate the point about how theory can stand in for those things like characterization and plot and explication (which is what I took people to mean by description), leaving room for setting and tone and voice and atmosphere to come more to the foreground of a work. Godard’s work is an extreme — almost a purified — example of this. But of course that’s not the only way theory can inform a work. Theoretical elements can be layered in on top of those as well as substituting for them, and that layered approach is far more common in the Booker books. I intended the comment about Godard largely as an aside to the conversation about the Booker, to make a point about one way that theory can function without evacuating aesthetics.

The equivalences I’m uncomfortable with are these materialist ones Domingos and Noah are talking about. A story is an idea. It can be materialized in art or in words or in dance or in whatever. There is dialectic there, and once manifest ideas can’t be infinitely translated among media, but I think where a lot of the theoretical richness is lacking is in the ideas we (critics, creators, and readers) start with, regardless of how they are manifest in any specific context. That’s why “paying attention to the art” doesn’t get me very far — if the underlying idea isn’t rich, it doesn’t matter to me how well it’s realized.

This is how I’d want the Godard point tied in: that banality of idea is especially problematic when the realization doesn’t make room for setting and tone and atmosphere and voice. American art cartooning is strikingly thin in those elements. But I loved Swamp Thing, which was full of characterization and plot and which trafficked in extremely conventional ideas (although I wouldn’t call it banal), because it made room for setting and atmosphere too.

You know…thinking about this a little more, I may be conflating two kinds of theory. There’s theory, or basically post-structuralism over the last 50 years. And there’s theory as any theoretical perspective/lens through which to examine art.

I saw Matthias’ statement, “Art isn’t theory,” as speaking to both of these definitions. Specifically, art isn’t post-structuralism…but also, art doesn’t have to be appreciated through a theoretical lens.

Certainly art isn’t post-structural theory. But…the point for me is that even if you don’t use post-structuralist theory, you’re using some sort of theory. There’s no unmediated response to art that doesn’t involve values/ideas/etc. which take part in a theoretical perspective (however unrigorous.) So the choice for me isn’t between art and theory, but between different types of theoretical approaches to art. To me, Matthias (and maybe Suat) seem to be saying that there’s an approach to art that does an end run around theory…and I just don’t see that being the case. (It’s possible I’ve misinterpreted Matthias though….)

Noah, I get a similar impression from what Matthias is saying, and I hope he’ll respond and straighten us out! I do think of it more as him saying that there can be a “purer” aesthetic experience than the one capital-T-Theory demands, though. Which gets into Robert’s point about accessibility and Matthias’ point about whether there’s “wrong” and right reading.

A book like Atonement is a good example, because it has an accessible layer and an less accessible layer. The Guardian’s wonderful review of the book comments on this: “It is a tribute to the scope, ambition and complexity of Atonement that it is difficult to give an adequate sense of what is going on in the novel without preempting – and thereby diminishing – the reader’s experience of it.” I hear both Matthias and Robert objecting to the insistence of that theoretical vantage point, as if it’s some kind of elitist bullying of the general reader. (Although Robert’s not a general reader so I’m probably misunderstanding him too…) But the effect of that position, in comics, is that there are no comics who take as their target demographic those readers who really really dug what MacEwan did with theory.

So to me, the objections to that kind of theoretical game-playing are what feels like a bias against literature to me. The expectation that we should value things that are fully accessible and purely aesthetic in the same way that we value things that make ambitious engagements with ideas is the objection that feels anti-theory and anti-literature to me. Literature stopped being about pretty words and started being about ideas a long time ago, so emphasizing aesthetics and letting creators off the hook for having brilliant ideas is a huge problem for me.

It doesn’t mean that ALL creators will have brilliant ideas — I read plenty of pulp and genre fiction and I like a lot of it. But I would be unhappy if there were no Booker fiction being written right now, especially if there were also no Dos Passos or Shaw or Ellison to fall back on when there’s a dry spell. Giving Mazzuchelli credit for what one admires about his art doesn’t also require letting him off the hook for not having the chops as a writer to create an adventurous idea too.

So to me it’s not just that there’s a suggestion of an end run around theory — although I agree, I think, that that’s there — but the suggestion that the quality of ideas in art doesn’t really matter, if the craft and the aesthetics are good. I don’t think that’s a zero sum game either.

Don’t know about Matthias, but when I answered for him I sensed that he was talking about French Theory (from the 60s and beyond). It would be pretty ridiculous to say that there’s a way of thinking about art which is outwith “theory” in the most general sense of the word.

I’m curious. Which particular theoretical vantage point did McEwan specify, Robert? Was it particularly dense or clever? It’s been sometime since I read it but I felt that “Atonement” worked best at the most accessible level. It doesn’t have the conceptual strength of many prior continental European novels from the latter part of the 20th century which probably explains its success. Nor does a book like “Never Let Me Go” for that matter. Which is probably part of the reason why I don’t like both these novels as much as I do those (due to my personal preferences, not any aesthetic ones).

Suat — I want to hear Robert’s answer to your question too but the Guardian review I linked to might answer some of your questions about Atonement. It wasn’t particularly dense or clever, but to me it was sufficiently dense and clever. (Saturday, otoh, was pretty much crap.) But you’re right that it doesn’t have the conceptual strength of its predecessors and that it’s strongest on the accessible level.

However, it does sort of exemplify how much the theoretical vantage point has become a set of “genre conventions.” I think Atonement’s a great beach book for book geeks. And I LOVE the fact that there are metafictional beach books now.

It’s worth noting that Atonement didn’t win the 2001 prize; this (more ambitious) book did.

For those without a NYT account, Caro is pointing towards “The True History of the Kelly Gang”. She leaves out the real horror – that McEwan won his Booker for a pretty bad book, “Amsterdam”.

Yeah, I just caught the link problem — it’s rerouted to go to the cache. Apparently if you google the book title the link to the NYT article works, but if you link from elsewhere it doesn’t? (Paywalls are weird.)

I haven’t read Amsterdam: I don’t go to the beach very often.

Noah: images can’t be the story if there’s no story to begin with, but I didn’t suppose that I needed to make such an obvious comment.

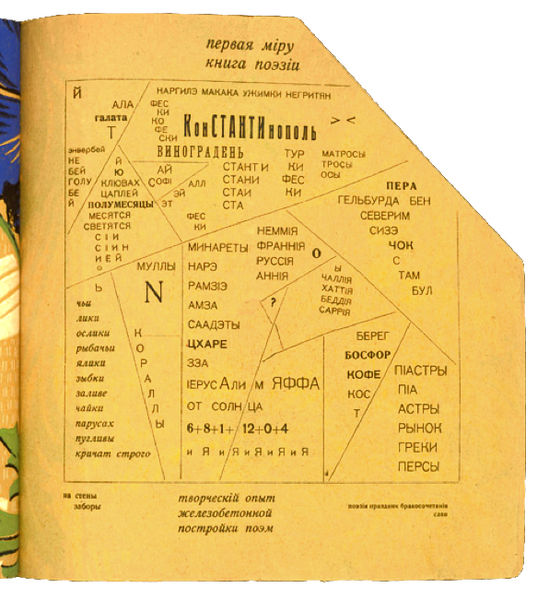

I must add that I agree with everything that Caro is saying here. If comics critics valued ideas more than handicraft Jochen Gerner would be in the canon instead of, I don’t know,everybody who actually is?…

The problem is that comics critics are just fans playing critics. (And I say “playing” because they value childishness so much.)

“It would be pretty ridiculous to say that there’s a way of thinking about art which is outwith “theory” in the most general sense of the word.”

I don’t know that it’s a ridiculous position, actually. Or at least…it’s not an especially unusual position. The desire for an anti-philosophy, or an anti-theoretical approach to art is of fairly longstanding I think — the idea that there’s a common-sense approach to art and being that is more true than a philosophical approach, or the idea that folks who do theory are the ideological ones, and folks who don’t do theory are non-ideological and are more true to the real work. Johnson’s “I refute him thus” is very much in that tradition. I’d argue that Johnson is refuting him by an appeal to theory…but I suspect Johnson himself would argue that his refutation is an appeal, not to theory, but to a stone.

Well, that last thing has more to do with instinct which has to do with habituation through experience (mental or physical), or in the case of neural reflexes, something innate. That can’t be Matthias’ position. An appeal to the mystical is fine on one level, but everything he’s written up till now suggests a theoretical basis. He’s undoubtedly inquiring about the use of linguistic theory/semiotics when it comes to images and hence comics. Why else would he bring up Krauss? I don’t know. Maybe something like how Clement Greenberg reacted to the reduction of painting to an “event”, “the by-product of which (the painting) is of no real concern to either artist of onlooker” (quote from Art Since 1900). Consider how Matthias wrote about Cezanne at his website recently – that’s one of the alternatives he’s talking about I presume. He should turn up soon to explain himself…

What do you guys think about Powr Mastrs, by CF? I don’t know if he reaches the Godard level of opacity– it doesn’t seem like it to me. There’s certainly a way you cold build a pretty Deleuzey discussion of abstracted vitalist narrative using his work, which is absolutely all about atmosphere and tone.

Noah writes,

I was talking about the former in my response to Caro.

Caro writes,

I’ve repeatedly tried to become more of one but all I succeed in doing is making myself more idiosyncratic.

My view of theory is that it is an accessory that most readers don’t use and are largely unfamiliar with, and I object to any implicit or explicit faulting of those readers for that. I fully believe that one can have an intelligent and edifying reading of an accomplished contemporary work without having to look at it through that prism. It’s great if one can, but I don’t think it’s problematic if one doesn’t. Look at The Matrix, for example. That’s pretty informed by contemporary theory, but there are millions of people who thoroughly enjoyed it who wouldn’t know Baudrillard from Batman. If ignorance of theory is problematic when it comes to dealing with a work, I think that says more about the work’s abstruseness than the audience’s limitations.

It’s been a while since I read Atonement myself. If anyone’s curious, here are my reviews for the novel and the film, which includes some additional thoughts on the book. Warning, though, both reviews contain spoilers.

I don’t think ideas from contemporary theory are the foundation for the book in toto. They’re the foundation for the ending. The strategies employed by the book up until then are pretty familiar from high-modernist fiction from the ’20s and ’30s. Geoff Dyer points to Virginia Woolf, and I would point to Faulkner, but he and I are pretty much on the same page on that score. As for the ending, it essentially demands that one go back and reread the narrative as the product of an unreliable narrator. The material isn’t compelling enough to ask this, and as I said, all I think McEwan succeeds in doing is completely upending the reader’s emotional engagement with the story. His handling of the metafictional revelation is very flippant, and it feels tacked on and pretentious. I should note that I do like the book quite a bit in spite of this.

It did win the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction here in the U.S. (Yeah, I know, those Americans and their literary tastes.)

That Cezanne article is here.

Quick clarification to Robert’s point: I don’t mean the challenge to more theory so much for readers as I do for critics and especially for creators. If anything, I think the comics world tends to underestimate readers.

(And I did mean that I consider Robert an expert reader, not that I think Robert doesn’t read widely and from diverse fields. Pulled out of context “not a general reader” seemed more perjorative than I meant it!)

The Matrix is dumb as dirt, though. It’s not responding to theory; it’s responding to probably at this point third hand tropes from Philip K. Dick.

PKD is very, very pomo, and extremely smart…I don’t think he read Derrida and Foucault, but he read a lot of philosophy, and his work is definitely engaged with that philosophy in lots of ways which resonate with post-structuralism. But Grant Morrison’s take on PKD is smarter than the Matrix’s overall, I think. For what that’s worth.

Caro–

I fully agree. I think artists’ and critics’ perspectives are always in danger of ossifying, and we should always be to looking to refresh our perspectives with new ideas. We have a responsibility to be familiar with theory, if for no other reason than its being the focus of so much contemporary dialogue. I don’t think leisure readers have the same responsibility, but I certainly invite them to look into it as well.

I think the comics world tends to overestimate itself.

Philip K. Dick is certainly a good poster child (har) for unillustratibility. There’s no way to show reality dissolving without implying a meta-reality, in a way that language doesn’t have to deal with, since it’s all constructed from the get go. Blade Runner and A Scanner Darkly demonstrate this pretty well, the first by changing the story completely in order to succeed visually, and the second by just being an obnoxious hairball of Richard Linklater goatee fluff.

Noah and Bert–

Out of curiosity, what did you think of the films of Total Recall and Minority Report?

Blade Runner is especially interesting in that it basically reverses the point of the novel. In “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” the point of the book ends up being that androids are inferior; the human cop kills them all with relative ease — which ends up ironically emphasizing human fallibility and weakness. In Blade Runner, the androids actually are superior — and human ability to create something greater than themselves points to a kind of transcendence of humanness, emphasized by the fact that Decker may be an android himself. So in linguistic/visual terms you could see the book as pointing to the fragility of the human and reality, and the movie as reifying both. (I think both book and movie are great.)

I only saw portions of Total Recall, but thought it seemed like a pretty entertaining film — it mostly avoided the point of the story, but kept enough that there are moments of genuine weirdness. It’s no Terminator (or Blade Runner) but it’s not bad. Didn’t see Minority Report. I’m with Bert about Scanner Darkly; I reviewed the crappy comics adaptation here.

Oh…and that essay by Matthias is really interesting in relation to some of these issues. I may not be following entirely, but he sort of considers the idea of Cezanne’s work as art outside of theory or meaning, but rejects it in favor of saying that Cezanne shows us something about human perception or the relationship between perception and the world. It clearly doesn’t reject theory…he says specifically that “there’s always meaning”…but at the same time I think there’s a primacy to being and perception — theory seems to come in afterwards (both in the essay itself and just in general.)

Anyway, folks should read it. It’s really good.

I agree that Matthias’ Cezanne essay is quite good. My problem with this approach to comics is that he needs to pretend that the stupid meaning isn’t there in order to praise the sacred cows.

It’s a pretty theoretical thing to, as Matthias does, dismiss explicitly any reference by Cezanne to Dutch genre painting, class commentary, and implicitly any reference to realism and image reproduction, in order to focus on the “pure” mechanics of visual perception. But the Impressionists in general want to move us from content (subject, context) to form (surface), so it’s certainly a sensitive following of their instructions.

I like both Total Recall and Minority Report (I certainly like Paul Verhoven way more than Spielberg in general, but it’s a pretty fun for being a Spielberg/Tom Cruise team-up). Total Recall is better. I sort of wish David Cronenberg would direct PKD– or at least I wish he had before he got all Oscar-happy. But he’s sort of the ideal guy to direct that kind of writing.

I think Cronenberg was slated to direct Total Recall when Richard Dreyfuss was supposed to star in it. Schwarzenegger got ahold of the property after that version fell through.

Domingos: “My problem with this approach to comics is that he needs to pretend that the stupid meaning isn’t there in order to praise the sacred cows.”

Well, you could say that with me too in terms of Schulz and McCay!

…and I may need to watch Total Recall again now….

Having watched Insidious and Antichrist in one night, I find it pretty stunning that someone would try to make conceptual sense of horror movies without the primal scene. Although I’m sure you could make an effort to think about the special effects and jump cuts and dark lighting as the sole instigators of anxiety.

Sorry, I’m really spotty in my internet presence at the moment. Immigrating will do that to you, I suppose. But thanks for the kind words about my Cézanne essay, and thanks Domingos for a comment that made me laugh out loud :)

And thanks Suat, for basically explicating much more clearly most of what I was trying to say.

I’ll see if I can address some of the issues I left hanging here:

While I do believe that meaning happens prior to the linguistic, I’m not trying to argue that a large part of meaning happens ‘outside theory’, whatever that means. As soon as we try to make sense of something, we’re on theoretical ground, as several of you have pointed out.

What I was saying was more in line with Robert’s point that capital-T theory (whether French or not) covers a particular set of approaches that I don’t believe necessarily have to take priority when creating or appreciating a work of art, or anything really. As interesting as Caro’s analysis of Eddie Campbell’s linguistic doubling was, it is far from the main reason I appreciate his work — setting, tone, character has much more to do with it, and are accessible much more immediately than the fascinating, but to me secondary, qualities Caro focused on (that is, to the extent that they can be separated, but bear with me…)

My problem with Theory, further, is that it doesn’t help me much in explaining or evoking my experience of some of the things I appreciate most in art — like the beauty and sense of life in Cézanne’s coloring, for example, or the compelling graphic vision of Hergé. Yes, these things can to an extent be theorized using French methods, and I like that a lot (both my Cézanne essay and my analysis of that Tintin page owe significant debts to different French thinkers), but it kind of still fails to address what I’m looking for — it’s a little like a written score compared to a performed piece of music, or something like that. To adequately deal with these qualities, I find poetical or otherwise evocative descriptive or associative language more useful.

And yes, I absolutely do think form and content are inseparable. Yes, we separate them all the time for practical analytical reasons, but often end up putting sticking them together again in a satisfactory way. This was my issue with some of the criticism of AP in our roundtable: the way the ideas are given actual form in that comic contribute and enrich their qualities to an extent that I didn’t think its critics here fully acknowledged. I still believe that book ultimately is something of a failure, and do agree with a lot of said criticism, but still think it overlooked a crucial aspect of Mazzuchelli’s meaning-making.

Blade Runner is the only great Dick adaptation, in large part for the reasons Bert and Noah describe, although I didn’t think A Scanner Darkly was *that* bad. Minority Report seems entirely to miss the point in its self-impressed occupation with spectacle, and the Matrix (a de facto Dick adaptation) is, as Noah so judiciously puts it, dumb as dirt.

The greatest thing about the otherwise rather messy and stupid Total Recall is the conversation Arnold has with himself in the beginning, where he’s wearing that towel on his head: “Get ready for a big surprise: you are not really you, you are me.” Priceless.

Noah: “In Blade Runner, the androids actually are superior — and human ability to create something greater than themselves points to a kind of transcendence of humanness, emphasized by the fact that Decker may be an android himself.”

Sidetrack (not that there aren’t millions of words already written on the book and film): Well, they’re not completely superior. They have a shortened lifespan both in the book and the film. This heightens the existential despair of the film, the whole “god is dead” (and we’ve killed him) thing, and the Christ metaphor. Dick’s book is less morose in its conclusion and obviously deeply concerned with the sanctity of life. The sheer obsession with the android animals (almost completely missing from the film) plays a large part in that. The makers of the film didn’t quite have Dick’s religiosity, but they seemed to communicate it through a somewhat ironic lens.

From Matthias’ Cezanne review:

“Cézanne’s pictures have often been described as ‘painting for painting’s sake,’ because they only rarely exhibit any real political, social, cultural or even emotional engagement, but rather seem to seek an analytical and sensory, neutral register.”

I would suggest that the pose of disengagement, the passive voyeurism of the flaneur (which found its more “radical” heirs in Situationism), has a great deal of valency with the French presumption of universal modernity, which has in turn become a way to neutralize differences, a grand aesthetic leveling that echoes the mercantile and democratic leveling of post-revolutionary capitalism. That normalcy should be taken for nature is a conservative ideological approach, not a neutral one– though this is not to deny that the review is informative and well-written.

I owe Noah an article and should be writing it instead of this comment, but Warren Craghead pointed me here and I guess I get a little riled by this whole line of discussion.

There’s only one way to verify Caro’s assertion, stated a few different ways, that lowercase-t theory or uppercase-T Theory have something important to offer comics. That is to create said comics and see how they turn out. There’s nothing wrong with suggesting that such-and-such might to be possible in comics, but there’s a huge problem with suggesting that “truly ambitious, truly literary comics” would come into existence if only the creators employed particular philosophical or literary models. Art just doesn’t work that way. Attempting to make it that work that way gives you mannerism. I call it the Shopping List Problem. One can see certain characteristics in a successful innovation of style, inspiring other creators to copy the characteristics. But quality in art is not a shopping list of characteristics, checked off and accounted for in the new work. It’s an integrated whole that generates forward from the intuited feelings of individual creators. The head serves the heart. The other way around is poisonous.

At least as far as visual art is concerned, Theory has totally failed to account for that aspect of art-making. In fact it has put concerted effort into demolishing the very notion of universal value, and replace it with these checklists. I recently learned that a friend of mine, a beautiful realist painter, is having a show of new work in which she has more or less discarded painting. The gallery is thrilled that the exhibition “will be strikingly conceptual in its trajectory” and that she has been “gradually moving in a more conceptual direction.” A conceptual program, of course, is the major item on the checklist of contemporaneity as subscribed to by a certain species of art-worlder. People used to take it as a sign of progress when figurative artists went abstract. Now people expect them to go conceptual. This is mannerism at its worst. I nearly cried.

With all due respect to Caro, I suspect that her idea of “truly ambitious, truly literary comics” is in fact comics that better emulate the characteristics she finds attractive in a particular strain of literature. Someone who finds those characteristics exciting, and I mean genuinely enthused, butterflies-in-the-tummy excited about them, ought to have a go at it. The rest of us ought to be left alone to pursue our ambitions and literary inclinations as we see fit to do so. Something entirely new might arise, not dreamed of in her philosophies. I hope she doesn’t subscribe to the arrogant presumptions of historical inevitability, finality, and perfection that makes the culture of capital-T Theory the moral and intellectual sinkhole that it is.

One more observation: A picture is only worth a thousand words when you’re dealing with description. When it comes to dense, complicated fiction, words become noticiably more efficient. It distresses me that comics critics calling for Booker-sized ambitions seem not to notice this.

Franklin, did you read the thread that birthed this one? The starting point for that discussion was relevant to your last assertion: the bias against “illustrated books” and/or using a lot of words in comics. When taking on “Booker-sized ambitions,” if words are more efficient, just use more of them.

Your comment demonstrates one of the most important places where making visual art works differently from making literature — and one of the ways in which the dominance of the visual art perspective limits the scope of expression represented within comics. Crafting a literary narrative is not an intuitive thing. It is always “mannered.” It is an integrated whole — but it does not “generate from the intuited feeling of an individual creator.” Literary structure follows models and theories, even if the “theory” is traditional poetics and narratological technique. You can’t feel your way around a 600-page novel unless you want that 600-page novel to be a rambling, solipsistic disaster. (I’m in the middle of a reply to Matthias that touches on this, with regards to the difference in what’s “immediate” from a verbal perspective as opposed to a visual one.)

Now, as I said in the post, I have no problems with people working in genres of comics that have nothing to do with literature. I admire and enjoy many of those comics. But I do have a problem with “literary” comics, ones that traffic in turf that literature’s spent a lot of time trodding, not actually paying attention to what literariness is and means, or how good writing and narrative craft works. Which is why I really like work by Eddie Campbell and Jason Overby, both of whom do literary things extremely well although quite differently, and why I like Asterios Polyp and Jimmy Corrigan a whole lot less.

This post, though, is about biases against literary thinking more broadly. The only thing I think is inevitable is that a culture that allows itself to have strident intellectual biases that foreclose engagement and conversation and appreciation of the full range of expression and creativity will produce a lesser variety of expressive creativity than a culture that embraces more.

Comics culture has a pretty strident intellectual bias against ambitious literature — something in between a bias and a chip on its shoulder. And it’s not just against theoretically ambitious literature; it’s against dense, complicated fiction period. There aren’t many comics comparable to Dickens or Thackeray or Swift or James or Ellison either — or even Austen for that matter. I think your post reflects that bias somewhat, in the idea that “dense complicated fiction” is not appropriate for comics because of the images.

But since comics is not, in fact, visual art, but something that draws from both visual art and literature, something that has as much access to words as creators decide to take advantage of, that is in fact a bias — a colonization, even — and it deserves some pushback. Because there are whole genres of expression that comics will never engage with if people who value those genres of expression don’t push back against the cultural dynamics.

Books like Fate of the Artist also push back, just by existing. One of the things that’s so brilliant about Fate (and Alec, although that’s less ambitious) is how well-crafted and well-chosen the shifts and choices are, between the work done by words and the work done by images. That was discussed throughout the roundtable — so I don’t think there was at any point a failure to recognize that words are probably needed to achieve these ambitions, only some degree of irritation and fatigue about how bad cartoonists often are at using them, and how unimportant many cartoonists consider verbal skill. I don’t remember where the comment was but I remember someone commenting that Campbell’s comics are lacking as comics because they rely on prose for the things prose does well. That attitude is an intellectual bias that’s just as big an sinkhole as any epistemological aporia coming out of Theory.

Noah: “Well, you could say that with me too in terms of Schulz and McCay!”

And me re. Mat Brinkman. No one is free from that capital sin. I do try to address the troublesome parts always though… And I almost never write about something that I really don’t like.

“That normalcy should be taken for nature is a conservative ideological approach, not a neutral one…”

Right; that’s John Berger (and lots of other folks.) Non-ideology, or non-theory, is an ideological and theoretical position, even if unacknowledged.

Matthias does go on to say that Cezanne’s work is not really painting for painting’s sake though — and he’s not entirely opposed to a Marxist reading either, at least as I read the essay….

———————–

Robert Stanley Martin says:

…to the extent that most comics critics are familiar with any outside medium, that medium is film. The serious study of literature and/or fine art is, I’m afraid, a little too demanding for our cohort.

————————

Surely so, in many cases. But couldn’t the fact that film is far closer to comics in its visual narrative nature (aside from its massive cultural popularity and influence) help make those comics critics more interested in and familiar with it?

————————-

This may also be why when you see a comics critic write about, I don’t know, James Ensor or Chris Marker or Thomas Pynchon, it has to be related back to comics in some way.

————————–

That critic may, however, be keeping in mind that readers know him as a comics critic, may know his writings on the subject. Or, that critic may be bringing up those creators while in a mainly comics-related website, where it could be understood there’s a good amount of interest in comics. So, relating them to comics helps keep things “on subject,” so to speak…

————————–

Domingos Isabelinho says:

Here’s a good example of what I said above:

http://tinyurl.com/3dyzfzo

José Luis Salinas was a great Argentinian master. In his _Cisco Kid_ strip above we can’t find many flaws. And yet it is wrong in a fundamental way: the bad guys are ugly, they’re sloppy (they didn’t shave) and at least one of them reminds us of a rat’s face. In a word they’re stereotypes. That’s why I consider this comic strip flawed both as literature and visual art…

————————–

The great graphic designer Milton Glaser praised “the power of the cliché” for its ability to quickly communicate to an audience running across an illustration, book cover, or advertisement.

Salinas’ depiction of the “bad guys” as obviously villainous-looking thus helps the reader (who is noticing one daily comic strip among many, in the course of a busy day) to react the way Salinas wants him to.

If, instead of a disjointed, serialized comic strip, Salinas had written a novel or put a painting on display in a gallery, then he could have counted on the greater, more concentrated attention given to “literature and visual art” by their intended audiences.

One may as well attack the lettering in a billboard for being bluntly simplistic in comparison to, say, an exquisitely example of calligraphy.

Yet — because of the way a billboard must work, to be read at a glance by drivers speeding past — ornate calligraphy, or complex messages, would be terrible for a billboard.

I have run into these notions before, namely that any kind of intellectual work done on behalf of art is theory, and that only theory stands in the way of sentimental or formal disasters. Both of them are mistaken.

Recasting traditional poetics and narrative as just another theory, even if you have to scare-quote “theory” to assert it, is certainly flattering to the culture of theory. Thus theory can be said to exist everywhere and at all times. I’ve even seen references to “Greenbergian Theory” as if non- or even anti-theoretical approaches to art merely constituted another theory. (For the uninitiated, the reference is to Clement Greenberg.) “Non-ideology, or non-theory, is an ideological and theoretical position, even if unacknowledged,” as Noah puts it. I’m sorry to be rude, but this is the sound of academic culture pleasuring itself. A finally fed-up Robert Storr wrote this in late 2009:

Speaking with a po-mo savvy young artist this week, I felt compelled to ask him what, given his approach to critical theory, was his attitude toward praxis? A puzzled look crept over his face, and, with a candour as admirable as it is rare among those who keep their verbal game up, he replied, ‘What’s that?’

The fact of the matter is that certain structures look good, sound good, or read well for some reason and seem ripe for reuse in an original way. Thus art progresses forward, by execution, not theory. When Caro claims that “You can’t feel your way around a 600-page novel unless you want that 600-page novel to be a rambling, solipsistic disaster,” I have to ask her how many 600-page novels she’s written, because that doesn’t sound right to me at all. I’m going to guess from the longer nonfiction I’ve written that really do have to feel your way around it, and you have to feel your way around it so thoroughly, self-critically, and intensely that the ramblings, solipsisms, and all the other weaknesses expose themselves as such. Then you root them out. Theory doesn’t save you from this work. As far as I know nothing does.

Are there broad biases against “literary thinking” in comicdom? I’m just as inclined to think that the Booker-style graphic novel envisioned by Caro would have to be the size of a children’s encyclopedia in order to achieve the same scope of ambition, because for certain narrative problems a picture is worth about six words instead of a thousand. Can one really just use more words? In my experience the words and the images have to sync at a certain rate or you’re not making comics anymore. We like making comics.

There’s something more than a little silly about critics, having trained on a certain specialty of literature, calling upon comics creators to acquire the same training so they can make equivalent comics. This is getting the cart so far in front of the horse that they’re not even attached anymore. Look, Caro, you’re a writer, you understand the literary angle that you’re looking for better than anyone, so do what I did when I wanted to see comics done a certain way and make the damn things yourself. As it is you might as well be standing on the sidelines of a football game yelling at the players to start playing hockey.

Matthias says:

“it is almost hypersensitive in execution, which has the effect of elevating the sensed into the world of ideas.”

And Matthias does hover on the brink of connecting the stillness of the images with a certain idea of time, which could relate to Deleuze’s film theory or Bergson’s duree, but by bringing it back to individuality and specificity his humanism gets in the way of his vitalism. But sure, connecting formalism to a certain critical-philosophical approach actual physics (as opposed to metaphysics) could begin to constitute a theoretical stance.

All the protestations of apolitical formalism seem unnecessary, though. Frankly, I think he could go more deeply into reminding people what it was that Cezanne did to make the fractured field of Cubism possible.

Oh, and for the record, I’m not at all certain that the world benefits from more creators reading theory and philosophy specifically. Critics sort of have an obligation to acknowledge and listen to others before they start sounding off, though.

Franklin, you’re ignoring the fact that there’s already at least one existing example of the kind of comics I’m looking for. Fate of the Artist not only takes on but fulfills these types of literary ambitions. So are you saying you think that book is not a comic? It’s certainly not as long as a children’s encyclopedia — it’s quite succinct, actually. And in the interview Matthias did, Campbell himself discussed the role curiosity about and investigation of postmodernism played in his crafting that narrative. So does it have the wrong ratio of words to pictures for you, or why is it that you’re not talking about it directly, as a real example rather than a hypothetical?

As for making comics, I partly take to heart Frank Kermode’s dictum that “reading is more important than writing.” I’m interested in critical and theoretical projects rather than imaginative ones. But I also think that you’re either missing or ignoring the context for this post: there are a lot of comics that get discussed as “literary” comics, and the problem isn’t really with those comics as such — it’s with the idea that they’re successfully literary. There are very few comics that hit that bar in a way that is recognizable to literary readers. Yes, it would be nice if there were more of them, and if comics defined itself broadly rather than narrowly, if they embraced ambitious literature as one model among many. But the critical imperative is to challenge the lack of analytical rigor displayed in calling those kinds of books “literary”. Criticism that is aware of literature, aware of theory, aware of what makes literary books literary, is the real goal here, so that we don’t call comics literary when they’re not.

As for methodology in writing, what I heard you say was that art was “intuitive.” There’s a difference, to me, between writing critically and intellectually and writing intuitively. You seem to be blurring those words together here — allowing the seamlessness that you experience in praxis to take precedence over the intellectual elegance that analytical writing can provide. It is of course your prerogative to prefer the seamlessness of praxis, and to aim to articulate that experience in your critical writing — that’s a related impulse to the kind of investigation Matthias is talking about. But if you blur them together, as you’re doing, uncritically giving intuition more value than analysis, as if the instincts are and must always be in control of all art, you’re just being sloppy — factually inaccurate about the role theory and analysis can play in some possible approaches to writing. And in really ambitious writing, keeping them separate is one of the ways an author can control the work and achieve that ambition. Here is a wonderful quote from the influential writing teacher John Barth, whose writing I greatly admire and who is “theoretical” in several senses, that illuminates the tension between these elements in fiction:

Franklin: “Thus art progresses forward,”

No it doesn’t. Art progresses sideways, if at all. Sometimes (often?) it retreats.

Isn’t praxis a technical philosophical term. Your project of privileging the production and craft of art is so thoroughly theory laden that you can’t even talk about it without theory terms even when you claim to be bashing theory.