In 2008, Steve Cohen asked me to contribute to a magazine to honor Gene Colan, to be entitled Genezine. I took the opportunity to arrange with Gene and his late wife Adrienne to tape an interview. We met at a pizza joint in midtown Manhattan while they waited for an appointment Gene had at a hospital nearby. Beforehand, I attempted to ink an elaborate drawing of Gene’s, in order to directly inform myself about his work’s structural properties and to have something to fuel the discussion. It was the last time I saw Adrienne, another reason why I regret that when I transcribed the tape, her many relevant comments were inaudible because the microphone in the little recorder I used had been aimed at Gene. Although the transcript is slightly disjointed without her portion of the interchange, Gene offers some interesting insights. For a reasons outside of Steve’s control, Genezine never came to fruition, so HU is as good a place as any to present this conversation with an important and influential comic book artist. Click on images to enlarge.

______________________________________________

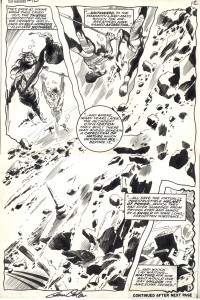

- The first time Tom Palmer inked Gene, from Dr. Strange #172

Transcript of an interview conducted on February 7th, 2008.

James: You like to work to music as a sound thing that’s going on…does that affect you compositionally? Your compositions tend to flow, and lead the eye around.

Gene: Let’s say it helps my composition, music helps me get into it.

James: In our earlier interview you said you wanted to find a way to represent music. I think you’ve done it! (laughter)

Gene: Well, Disney did that with Fantasia.

James: Comics don’t have sound, but there is timing, the beats.

Gene: I’ll play anything. I’ll handpick the records. A symphony, whatever it’s going to be, and that launches me right into it. Blocks out anything else, and it kind of blends with what I’m doing. Sometimes I’ll play just sound.

James: Do you find that produces a sort of time warp, you get lost in what you’re doing?

Gene: Ooh, yeah.

James: Like missing time…how long have I been here? (laughter)

Gene: Yes, because music launches me into another time, another space, and that helps me a lot. It’s very hard to describe just what the mental process is…everybody a different way of approaching it. But, that how I approach it.

James: You are able to visualize a three-dimensional environment in your comics, what I call “motion perspective.” In other words, you are able to portray different angled views of a given environment, with some elements in motion. For instance, you vary vantage points within the six sides of a room, on furniture, the people moving through it in time, and what can be seen through the windows and doors. These skills are specific to cartoonists and animators, and you are able to manifest it so realistically, and with your style of graceful, expressive page design.

Gene: I’d get an idea of the form and light from something in a photo or on film, and I’d take it from there. One of the reasons I prefer taking my own reference pictures is because I’m able to shoot pics of some elements from different angles. Especially people. Of course, there’s much more to it. I can tell you also that when I read the script (even if it’s only a page or two), I’m planning the composition of the panels for days in my head, looking for different elements to take pictures of and deciding the best way to portray the words.

James: Photos and film give you light. Would you pose yourself?

Gene: Sometimes, yeah I did.

James: Like the Nightmare drawing I inked, you obviously didn’t have a model for that thing. (laughter)

Gene: Well, sometimes I need a springboard.

James: If you’re doing a long piece with the same guy, like Nathaniel Dusk…at a certain point you’ve got him, you can draw him all the way around.

Gene: Yeah.

James: You would go to different locations, to find something specific that would be a springboard?

Gene: I would get an mental image, right away, or sometimes not right away, but I would get an image of a location and the person in it, what’s in the foreground, what’s in the background, and I would work with that to get a sense of depth. Very often I would use something in the foreground to frame the picture, something recognizable, like a lamp.

James: I see…it’s not really the focus of the image, but something to make the space.

Gene: Right. Then I’ll work into the background, or sometimes I’ll work right up front. I have to have a good notion of where they are. If they are in a tunnel underground, that’s not much to work with.

James: In your story in The Escapist #2 (Vol. 1 of the collections) you draw the characters in a tunnel, and they’ve got no room. You do a claustrophobic thing, and find a place to hide the “camera,” imbedded in the wall back here (holds an imaginary camera behind his head). It’s not a real view, but it works.

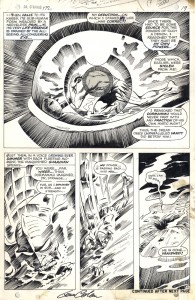

- Dan Adkins puts a nice polish on Gene’s pencils, from SubMariner

Gene: They’re not complete images, they’re kind of fragmented…but I generally know what it’s going to be. And once I start doing the figure work it becomes clearer and clearer what I’m going to put into the background.

James: Okay, but also you don’t read the entire script, right? You prefer to be surprised?

Gene: Page to page, page to page, or if everything feels like it is leading to a particular page that I don’t know about, then I’ll read forward, to find out what that place is…I have to, or I’ll screw it up, you know. I mean, sometimes it has to do with something that is going to appear later…but they are usually pretty basic. It usually starts out in a basic way, two people talking. You don’t need much more than that.

James: I wanted to get into your acting. I mean, your characters act, within their framework. So even the smallest little guy in the background has a role to play…he’s not there by accident, you already cut out all the extraneous…so each of those would be based on types from film or from your life?

Gene: Yes, things I’d seen on the screen…

James: Or your family…

Gene: Oh yes, my son.

James: You put Adrienne in there?

Gene: I used to, yeah, and my daughter.

James: As goddesses? (laughter)

Gene: Did you see the film Patton? There’s a particular scene in it where there’s a close-up of two Generals, Patton and someone else, talking about their next strategic move. During the thick of the battle, way in the background shells are being lobbed all over the place, explosions, everything, and the camera was focused on these two generals. But, if you looked in the background they were telling another story and that story was, a GI had been shot, wounded, and a medic comes running to him. It has nothing to do with what’s up close, that was the important thing and that was the thing that has dialogue, the generals talking, what they’re going to do next; the background essentially relates to it, to where they are and what they’re about….yeah, we all knew it was wartime, but to see a medic come out and help a wounded soldier and drag him back to safety…they didn’t have to put that in, but boy, what reality. It added to the scene.

James: Okay, for instance at Marvel with Stan Lee, if you have a conversation on the phone, it goes for….how long is it?

Gene: A few minutes. I’d tape it.

James: Right. So you’d actually refer back to the tape while you’re working.

Gene: Yes, that’s what I did.

James: You have to plan out all the action and movement…and that’s actually an optimum kind of freedom for you to design everything.

Gene: It’s not done that way anymore.

James: Okay, now they say, here’s four panels on this page, and the editors do futz around with the balloons…do you pencil the balloons in first? Or leave room for them?

Gene: I try to leave some room at the top.

James: I can’t design a comic page without putting the balloons in first, because I know I’ll need this much space. Anyway, at Marvel you were writing the story on the top, your originals have notes in your handwriting.

Gene: Those books would never have long sentences, just very short captions so it wouldn’t crowd out the art. Stan gave me the ball and let me run with it.

James: Well, for instance in Dr. Strange #182 there was a two page spread with the Juggernaut, a very psychedelic layout, a few panels rippling across a spread with gradating colors on the page behind, a really unusual resolution….you’d make that decision?

Gene: Yes.

James: You’d say, ‘I’m going to do this two-page spread,’ and then for that space you might have to pay on the last page by having to pack in a lot of information for the end.

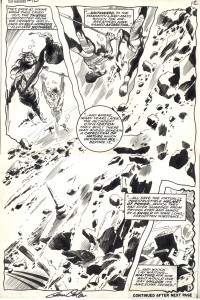

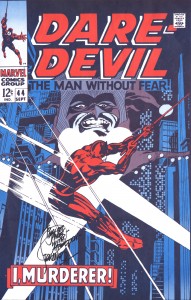

- Anatomies clash over an effective background, in the print Jim Steranko made of the cover he inked for Gene.

Gene: Oh yeah. But sometimes there were issues that the panels weren’t clear enough. Stan would say to me, ‘Find the man in the puzzle.’

James: Yes, but it would make complete sense when it was colored. They just weren’t able to see how it all came together, right away. Marie Severin or whoever colored it would think, ‘Oh, I see what he’s doing here,’ comprehend it, make it clear.

Gene: I did more of what pleased me than what pleased Stan. I didn’t disregard what he wanted, but I worked for many writers, and I did what pleased me. I thought that was the right thing to do.

James: Your body of work has a consistent kind of realization.

Gene: I had some writers that were editors, who were very specific about what they wanted, and that would intimidate me, and then I’d start to worry about the work, and they could never get the best out of me because I had to follow what they wanted.

James: They should want the artist’s vision. Otherwise, why hire you? I find penciling to be the most pleasurable part.

Gene: It is.

James: For a long time I didn’t enjoy the inking, it was like doing the same drawing over again. I’d ask, can’t you get me an inker? But no one else could ink it because they wouldn’t know what the hell it was.

Gene: I inked a few things when they asked me to. But, editors and writers want what they want. They often don’t care what you want.

James: Or, the writer would not understand what the artist was facing. They’d say, give me 200 people standing on a street corner. Thanks for that!

Gene: I’d give the effect. There’s a story I like to tell, about an artist Alexander King who did a painting of a street corner full of figures, and the editor said, ‘Can’t you just turn everybody to the left?’ That meant the whole painting was destroyed. They’re not pawns on a board (laughter). So King just folds the painting in half and dumps it in the trashcan and walks to the elevator. There was another fellow in the room who was watching the proceedings, observing, and he followed King out to the elevator. He said, ‘Let me give you a word of advice. The next time you do something of this nature, paint one of the women with a hairy arm. If you did that, they’d spot that right away, and justify their job’ (laughter).

James: That’s like what I read Adrienne said to you at some point, fixing one of Shooter’s corrections on every page….

Gene: ‘Make him feel like you fixed everything.’

James: And he’s like, ‘That’s more like it.’ I didn’t mean to bring him up (laughter). About inking again, your own inking is very fresh and quick, like you actually did it kind of quickly.

Gene: I have a rough finish with ink.

James: It’s not something you want to be doing, really?

Gene: No, I don’t. I can get a suppleness of tone with a pencil, and let the inker decide whether he wants to put those greys in or not.

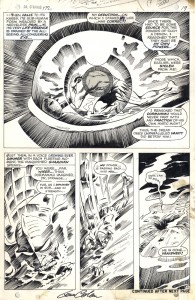

My try: I should have used a brush

James: Well, inking your Nightmare drawing I realized that all of your lines are going in a trajectory. When I printed it out I should have flopped it, because I’m left handed…are you right-handed, Gene?

Gene: Yes.

James: Right, well, your directional strokes are going like this (demonstrates). I would have done it better backwards (laughter).

Gene: I’m a stickler for faces. And you got Strange spot on. Overall, a little too scratchy with the lines. But I know that’s very much your style which works brilliantly when doing your own art, but I’d like to see mine with a little more mix of pen and brush work.

James: That was my second try at inking that drawing. I printed it off your site and blew it up on Xerox, then lightboxed it. The lightbox made it very hard to see the lighter lines.

Gene: Your inking is quite good and actually it’s really how I drew it. If you had put a denser line on the back of the monster, it would have improved the confusion. You couldn’t have picked a more complicated picture. (laughter) You should have started with something simple! It’s confusing because that’s how I drew it. Bottom line: ya did good, Joey!

James: Well, thanks, Gene.

Gene: Let me ask you this. Supposing on the page it’s raining, and you’re focusing on some of the characters, rain streaks are coming from right to left. But now you’re focusing on this character, who’s talking more or less to the reader. There’s another panel where he continues to talk, but not from the same angle.

James: You’d have to change the direction of the rain.

Gene: Right. Did you do that?

James: Yeah, my first issue of 2020 Visions started with a rain scene, and I angled it depending on the viewpoint. But in inking you, it’s in the faces that you go, oh my God, that’s really Gene. The way it wraps around the form of the head…

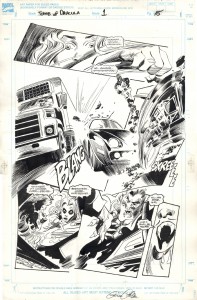

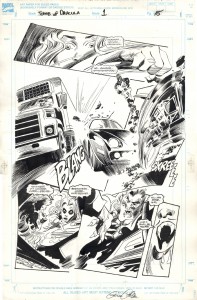

As an inker, Al Williamson 'gets' Gene, from Tomb of Dracula (miniseries) #1.

Gene: When I draw a face with an eyeball in it, very often that eyeball is so bloody outstanding, that it almost looks like they’re looking at you in shock.

James: (laughs) The eyeball!

Gene: I mean just a general face talking, so I try to soften that, so that, if you look twice, maybe the first time you moved to the eyeball, but if you looked at it again more carefully you wouldn’t see it. You know what I mean? I have the eyeball in such a way that it’s not offensive. It doesn’t look like it’s scary-eyed. Do you understand what I mean?

James: You mean a specific piece with an eyeball?

Gene: No, when you draw a face, say a guy…

James: You mean whether it comes to life or not?

Gene: Well, it can come to life, but if you’re frightened, of course, your eyes are wide open and you can’t help it…you have to show the eyeball. But if you want to keep that brave look on a hero, then don’t show the eyeball.

James: Well, certain cartoonists will…and I was doing this. I used to draw an eye, and put a little highlight in the pupil…a little gleam.

Gene: Yeah.

James: Then a couple jobs I just blocked it in. It causes this sort of Charlie Brown effect. It becomes a little more universal, people identify with it in a different sort of way.

Gene: I find when you’re dealing with that specific thing that I’m talking about, the eyeball, it’s either over the top, or it’s hidden, so that it’s not offensive. You don’t get the feeling that this guy is staring at you. It’s all in the eyes, like softening. They could be looking at you but there’s just a hint of an eyeball in there. Just a hint.

______________________________________

My earlier interview with Gene from 2002, at Comic Art Forum: http://www.thearteriesgroup.com/ComicArtForumColan.html

______________________________________

Daredevil, Sub-Mariner, Tomb of Dracula, Dr. Strange, and Nightmare copyright 2011 Marvel Comics. Nightmare drawing copyright 2011 by Gene Colan.

And now we kick off the actual elf quest of Elfquest! New clothes, new elves, old acquaintances, and a party when you least expect it.

And now we kick off the actual elf quest of Elfquest! New clothes, new elves, old acquaintances, and a party when you least expect it.