(this post is a part of this month’s Manga Movable Feast, hosted this round by Derik Badman and the Panelists.)

Cross Game Review Part the First—The Self-Serving Enthusiast

If you haven’t yet purchased and devoured the first three/seven volumes of Cross Game yet, and you have no fear of either sentiment or baseball, then I would that you do so now. Go ahead—I can wait.

Done?

Good.

I’ve tried to avoid writing review-like pieces in my brief spin as a writer, and that’s generally because when I really like something my impulses tend towards a kind of uncritical boosterism, and when I don’t like something, which is, well, most of my life, I seem incapable of having a more moderate reaction to the material that might lead me to being able to even-handedly write about it in a method that would even approximate objectivity. So I haven’t even finished the first full paragraph and already I’ve violated my personal standards for the sake of this series.

So why exactly do I want you personally to buy copies of Cross Game for yourself and all of your friends and relatives? Like most of my motivations, it’s selfish. Adachi is one of my favorite cartoonists, and while I’m pretty damn enthusiastic about Cross Game and his return to baseball, I’m even more thrilled with Touch, his early eighties classic that Cross Game echoes in so many ways. And my ability to one day read Touch in print, in English, depends on you and your deep comics spending. Let’s make this happen, shall we?

Part the Second- Seeing Stars

Punchy plot summary! Adachi Sensei, Oh great flaming star of manga! Four decades of comics! Still alive! Still writing about teenagers! Four stars!!!!

Part the Third, in Which the Reviewer, Failing to Avoid the Worst Aspects of His Own Editorial Impulses, Pens an Overwrought Description of the Book As a Physical Object

For a week this March I slept on a succession of couches, spending the days wandering Seattle with a green duffel filled with a few posessions; my inking supplies, paper, various clothing and toiletries, my spiral notebook, and several books, including the second volume of Cross Game. The fourth day was particularly hard on me—it seemed like there was no where I could just sit and rest for a while without causing a problem for someone else. I kept on thinking about that green-backed volume two, so sleek, compact and inviting, and how it had looked on the night stand next to its partner, back to front, spooning in a little pile, the orange overbalancing the green by its larger size. They seemed so right together at the time, but now they were separated by miles of distance, and by unrelenting necessity.

The cover design is streamline, almost minimalist—painted figures on solid fill, a curly-cue logo and modest indica. It feels slick and modern in one’s fingers, defiantly in opposition to the slightly aged style of the artwork itself. The off-white pages smell of fresh paper and promise that they will stay there, bound together, pressing and yet somehow at rest, until they are one day opened again, held apart by scissored fingers, suspended in the moment of un-touching.

Part the Fourth, In Which the Reviewer Puts Forth a Clever Analogy That, Whilst Possibly Interesting, Won’t Actually Hold Up to Any Scrutiny

Baseball=Making Comics.

No, really. The whole baseball package–the skills building, the isolated mental game of pitcher versus batter, pitcher versus himself, the vast audience waiting to be surprised, entertained, let down, the fate of the game constantly in balance… It’s hard to escape the idea that when Adachi is talking about baseball, he’s also talking about making comics, about the thrill of watching one’s self improve, of pushing, of hitting a barrier only to break through to the challenge previously unseen. Aiming for the top. The sweet satisfaction of an aptitude well-developed, of a lifetime of skill coming to bear on a single moment.

Part the Fifth—Vaguely Related Autobiography

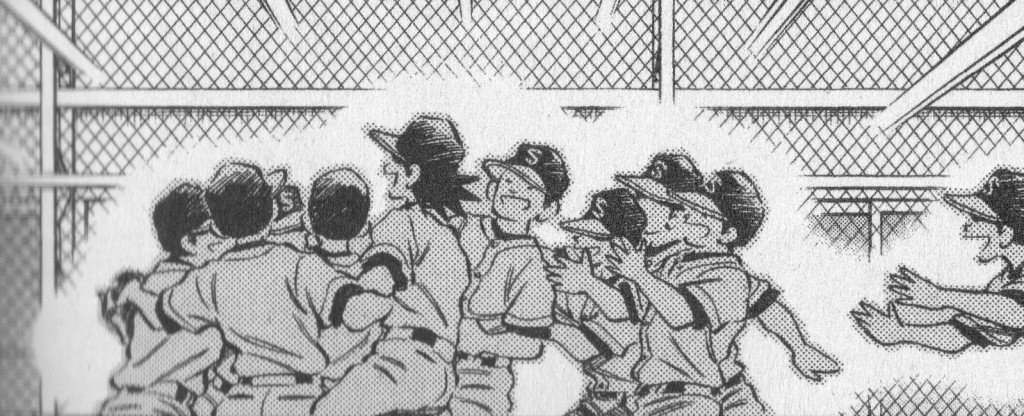

When I was seven I was a member of a coach-pitch little league team called the Pirates. Before each game our coach would give us a mini-pep talk/lecture about how important the day’s game would be, and how we needed to focus and do our best, before sending us off with a team chant: “PIRATES! PIRATES! PIRATES!” I occupied center field, a position which, in most of our games, was more nominal than functional, as seven year olds aren’t generally known for their devastating long drives.

On one particular day, the other team had a flurry of the aforementioned very rare outfield hits, including several that were completely over my head. I did my best to field them, but as the game wore on my failures as an individual had me feeling more and more dejected.

When the game finally, mercifully, came to its punishing conclusion, the coach gathered us all up in the customary circle in front of our Pirates dugout. His face was red and his mustache quivered like a caterpillar beneath his nose. “That was pathetic. You all were pathetic. No, you were pitiful. That wasn’t baseball. That was something… something not baseball.” His shoulders raised and lowered with each breath. “Put your hands in, everyone. Pitiful, on three. Everyone.”

“Pitiful, pitiful, pitiful,” we chanted, some half-heartedly, some through sobs, some shouting as if humiliation were the greatest gift of all.

Part the Sixth, in Which the Reviewer Presents Several Close-ups of the Artwork for the Reader’s Examination

Part the Seventh, in Which the Reviewer Abandons His Conceit for The Pretense of No Pretension

History, and the comics canon, are strange things. What place did Gasoline Alley occupy in critical attentions five years ago? Over the same period of time Yoshihiro Tatsumi has gone from a footnote in manga history to being regarded, to certain English-speaking audiences, as an exemplar of an entire movement.

In both cases, what changed was not the artists themselves, but the availability of their work.

This shifting ground has the potential to drastically change a reader’s reaction to Cross Game. To English-oriented monoglots, who have previously only seen two short story collections by cartoonist Mitsuru Adachi, Cross Game is an assured, uniquely-paced and tempered debut that flicks effortlessly between breezy action and moments of unexpected, intense longing. For Japanese readers, Cross Game is a victory lap. (or, at fifteen 200-page volumes in its original release, perhaps a victory marathon).

Cross Game was initially serialized in Shonen Sunday starting in 2005, when Adachi was 55, thirty-five years and tens of thousands of pages into his career. Adachi has spent most of that career creating clever romantic “comedies” that often feature more than a hint of tragedy and melancholy. More often than not his stories center around young athletes, along with all of the attendant conflicts and triumphs of that world.

Cross Game itself most closely resembles Adachi’s breakout 1983 series Touch, which, following the also-popular Miyuki, furnished him with his second anime adaptation, as well as his most lasting fame. Several of the elements that make Touch so unusual in the company of other popular entertainments are present, albeit rearranged and realigned. The childhood friends and childhood promises carried into the future. The gently melancholic tone and strangely passive protagonists. The sense of time as a construct of memory, sometimes a fraction of a second in a series of pages, sometimes years in a single frame.

I’ve never read a comic before where both the benefits and potential pitfalls of weekly serialization are so starkly clear. With the aid of his squadron of assistants, Adachi had drawn, at minimum, a thousand pages a year for over thirty five years by the time Cross Game debuted, and the result is some of the most natural, and readable, storytelling I’ve ever seen. Complex actions and coordinated sequences play out effortlessly, several lifetime’s worth of breakdown skills and gesture drawing coming to bear on the trickiest problems. But the solutions themselves never veer into overly-flashy results, instead using a myriad of design solutions to preserve a clear, natural path over the most seemingly-complicated layouts.

The sheer amount of pages available to him by virtue of his assistants means that Adachi can afford to tell a different kind of story. It’s hard to imagine a better way of depicting baseball sequences than the method that Adachi has arrived at over his thousands of pages of baseball manga. Just like our memories of a real game, we come in and out of the action, the narrative sometimes summarizing, sometimes lingering. In comics, time is a function of space, and Adachi has the space to give us time.

Adachi also uses this space to leisurely unfold the action, giving us quiet moments of reflection between actions, sometimes serving as transitions, and other times acting as a pause, a moment of breath in the midst of so much action and movement.

And then there are the downsides to that unrelenting weekly crunch. All those assistants mean professional but at times undistinguished backgrounds, which wouldn’t be as obvious a defect were it not for Adachi’s expressive, calligraphic inking line, which is sometimes at odds with the comparatively dead line weight of the backgrounds. More damning, occasionally a chapter seems to be just marking time until the next main plot movement, and these deviations from the overall arc have the added problem of often veering into genre cliché. (the most egregious example so far is a first volume detour involving beaning a fleeing criminal with a baseball)

The improvisatory nature of the story line sometimes trips Adachi up as well. With certain major plot points it seems impossible that Adachi didn’t plan them well in advance, as the needed elements are in place well before the events themselves. Other times, however, Adachi succumbs to the dreaded serial fiction trick of introducing a new element pages before it will be called into use, drawing attention to the artificiality of plot construction itself. Occasionally Adachi, through his narrator voice, draws attention to this himself, presumably with the intent of diffusing the awkwardness with some humor, but not always to good effect.

Ultimately, though, Adachi’s faults are more Freaks and Geeks than Friends, a result of his ambition rather than a lack of same. His failings, when they arrive, are forgivable, and seeming part and parcel of the weekly manga treadmill. Cross Game is assured, confident and wistful, and if you have some tolerance for genre and overt sentiment, there is much here to admire and, most importantly, to experience and enjoy. When you’re aiming for the Koshien, it’s summer forever.