Look, the last thing I want to do is harsh on Steven Tyler. I love Steven Tyler. I probably wouldn’t want him spending the weekend at my house because, face it, he seems pretty high maintenance. But in a more abstract way, I love him.

Look, the last thing I want to do is harsh on Steven Tyler. I love Steven Tyler. I probably wouldn’t want him spending the weekend at my house because, face it, he seems pretty high maintenance. But in a more abstract way, I love him.

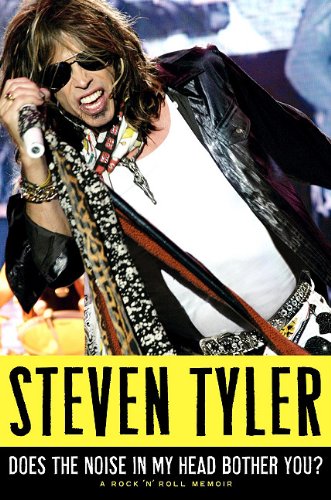

And I pretty much loved his book, Does the Noise in My Head Bother You? It was very entertaining, and many of the things you want in a rock biography. The relative sizes of Aerosmith’s respective dicks, for instance. See? You want to know, right? I was also charmed by the pains Tyler seemed to be taking to be as kind as possible. His claws certainly came out a time or two, especially when he started talking about drug and band issues (one in the same, pretty much) from the mid- ’80s on, but overall I give him points for trying.

I didn’t read this book because I love Aerosmith, although I do (well, I love about five years of Aerosmith’s career, from 1972-1977, and am indulgent about another few years shortly thereafter, especially Joe Perry’s solo albums). The specific reason was that I read Cyrinda Foxe’s biography, “Dream On: Livin’ on the Edge with Steven Tyler and Aerosmith” (a euphonious title if ever one I did see). Cyrinda Foxe’s book was pretty damned interesting. She was associated with Andy Warhol’s crowd and married David Johansen of the New York Dolls before marrying (and then divorcing) Steven Tyler, so as you might imagine, she had Things to Say.

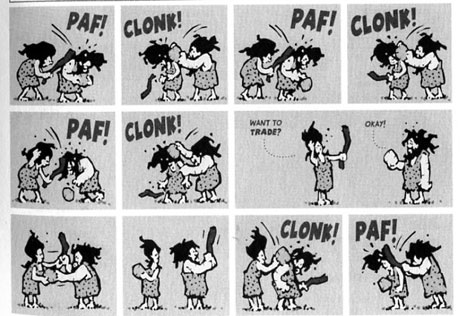

Now, it’s stupid to assume that you’ll like someone just because you like his music. People often become rock stars because they’re narcissistic assholes, and cocaine doesn’t make that situation any better. But “Dream On” made Steven Tyler sound like a monster. A minor monster, I guess, but the kind of guy who lies and cheats and doesn’t give a damn about anyone other than himself, including his wife or his daughter. Cyrinda wrote about a man who was completely out of control, cruel and miserly and interested in nothing besides his drugs and his band. (She was an innocent in all of this, of course.) And I can see that, to a point, but she protested too much.

And most of her protests involved a perceived lack of fabulosity re. their living conditions, which makes me wonder. Instead of taking her to an amazing New York apartment after their marriage, she said, Tyler took her to a disgusting, filth-crusted hovel in the wilds of New Hampshire, which you’d think was located in Darkest Peru or something, from her description. And then he expected her to do things like clean up after herself and cook food. And he didn’t buy her things. She left her exciting life in boho New York (where she lived in a hovel with David Johansen) to be with this big rock star, and he didn’t pay out properly Well, I don’t know. She didn’t marry Tyler the moment she met him – in fact, she was around for awhile before leaving her husband for him. Where he lived never came up? Not once? I can also kind of see how someone who’d suddenly become a big rock star and had been touring nonstop for a year or more might want to go someplace that was comparatively safe and quiet. Cyrinda Foxe was many things, but rational doesn’t seem to have been one of them. (Same goes for Steven Tyler, of course. Two irrational, high strung, drug-addled showboats does not a solid union make, apparently. Who knew?)

Foxe also claimed that Tyler later dumped her and their daughter Mia in another hovel in New Hampshire while he toured and lived the high life. (Ha! Get it? The high life!) She was on her own, alone, and he didn’t give them any money at all, and she had no way of getting back to civilization. She also claimed there wasn’t a problem with her own drug abuse, and all of that seems unlikely. (How hard can it be to get out of New Hampshire?) Tyler was on the road constantly, and he certainly did cheat and do a staggering amount of drugs, but their relationship was obviously a train wreck, and train wrecks are a two-way street. Or something like that.

There were good times, of course, mostly involving partying and expensive jewelry. Foxe described a touching moment on the road with Aerosmith where she expressed admiration for an insanely expensive bracelet she saw at a jewelery store. That evening, Tyler pulled back the covers and displayed said insanely expensive bracelet adorning his dick. As she squealed in delight, he told her to dive for it. Oh, darling!

So, fascinating and lascivious and stuff, but leading to a number of questions. So, I was eager to read Tyler’s side, thinking I could maybe merge the two together and divide by two and come up with something , you know, truthish. It worked, to a degree – although I might also have to read “Creating Myself,” Mia Tyler’s 2008 biography (Mia is Steven and Cyrinda’s daughter). (She is a lovely woman, but I have serious doubts about her literary abilities.) I’ve already read “Walk this Way,” the 1997 “biography” of Aerosmith by Stephen Davis (who wrote “Hammer of the Gods” about Led Zeppelin), and I partially reread it after finishing “Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?” (answer: no, but your title does). Because, you know, I do shit like that. Anyway, I have finally come to some (obviously dubious) conclusions about this man I don’t know at all.

He is not the most self-aware pencil in the sea, Steven Tyler. I can hear your collective gasp of outrage and shock now. Steven Tyler? Not completely on top of his shit? Well, yes. That’s my main takeaway. It only bears mentioning because he seems to feel that he’s done enough rehab and soul searching and so on that he understands things now and can present his story objectively, and get preachy about my Xanax. He tells me that it is a crutch and he knows what I’m really doing because he’s been there. (His error is that I take Xanax as prescribed for an actual problem – a concept he has apparently never considered – while he snorted pounds of Xanax to get high.) (Snorted.) (Anyway.) He is angry and resentful and feels the band has done him wrong, especially guitarist Joe Perry, and he will not forgive them for telling him his drug problem was completely fucking out of hand. (It was.) His main justification for this resentment is that the rest of the band was fucked up too, especially Joe Perry. And while that is no doubt the case, it just makes the extent of Tyler’s drug use even more impressive, rather than diminishing its scope in any way.

This is as good a time as any top point out that a lot of Tyler’s book is about drugs. A lot, a lot. I was expecting that, though, because it’s a story about Aerosmith, and Aerosmith was about drugs. That’s what they did. They toured and made music (and Tyler does also include a lot of delightful anecdotes about how certain songs, lyrics, and sounds came to be – I found out, for instance, that he says “‘cept for my big ten inch” in “Big Ten Inch Record,” on Toys in the Attic, not “suck on my big ten inch – a bit of a disappointment, really, partly because on of my favorite childhood memories is of my aunt walking by my cousin’s bedroom when that song was playing, stopping for a moment to listen, and saying, “That braggart!”), and they took drugs. Those things were on equal footing. And taking massive amounts of drugs narrows a person’s world so much that a man like Steven Tyler can look back on a time when he had the world at his feet, and what he can tell us about it is where he hid his tuinals and how he managed to snort cocaine during the shows.

Tyler also makes many of the expected excuses for generally being an asshole – although the behavior he is excusing is in many cases not what anyone might expect. Taking legal custody of a fifteen-year-old girl so he could have sex with her, for instance. He explains this by saying he loved her. (Oh. Well, then. Who can argue with that?) I’m largely unflappable, as far as getting exercised about sexual mores, but I admit that I do look at this episode askance. (Tyler talks more about this in “Walk the Way,” by the way, saying the girl had several abortions and was badly burned in a fire in their apartment while he was on the road – he said she was too young to be left alone, but he couldn’t take her with him, so…) Anyway, he has his reasons. Everyone does. For the most part, the excuse-making isn’t excessive and he’s willing to make himself look pretty bad. I respect that.

This balance holds until roughly the second half of the book, when he starts to lose his grip. I have a theory about why Tyler can be more or less reasonable about the events that happened before the first time he went to rehab, but not anything since. That reason is that he was so high, all the time, that he can’t really remember what happened before he went to rehab. (That would also explain some of the factual discrepancies between “The Noise in My Head” and “Walk this Way.”) Since going to rehab, and going to rehab, and going to rehab, he’s had some moments of sobriety and thus actually remembers some of the things that have happened in the last twenty years. I find that things are more annoying when you remember them.

And that’s enough, really, about Steven Tyler’s book. I just remembered that Aerosmith drummer Joey Kramer wrote a biography a few years ago, so I’m off to download that sucker to my Kindle (unless I have to buy the printed edition so I can look at the pictures). If it’s any good, I’ll let you know.