What follows is self-reflective, self-indulgent, and only tangentially related to comics. Topics covered—paralysis, instant gratification, illustration, the nature of desire. Not covered—ranking, freelancing, the problems of failure versus the problems of success. Consider yourself informed!

Regular readers to this website may know that this March, an article co-authored by Joy DeLyria and myself had a round of unexpected exposure, linked to and written about on dozens of sites, and seen by an unfathomable (to me) number of people. The experience and its aftermath was surprising, gratifying, but also paralyzing, and I was left for a long time afterward with a great difficulty in drawing at all. Leading up to the article’s publication I had been drawing upwards of ten hours a day, so this was a dramatic change, to say the least.

I had only been writing at all for only a few months at that point, having been asked to contribute to the Hooded Utilitarian after arguing with editor Noah Berlatsky on various topics both educational and aesthetic. A handful of my initial articles attracted some attention, at least at the scale of the modestly-scaled comics scene. Most, however, disappeared after a few days, as quickly as they came, the reaction to them in proportion to the moment that made them.

But this one seemed different.

It’s difficult now, some months after the fact, to describe the elation, giddiness, and eventual panic that set in as our Wire article went from casual blog post to high traffic blog post to server-breaking feature article. The excitement is perhaps most understandable. The panic, however, might require some additional explanation.

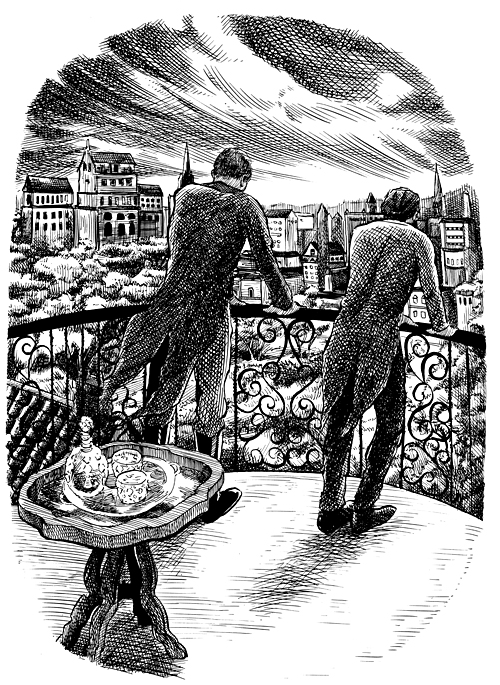

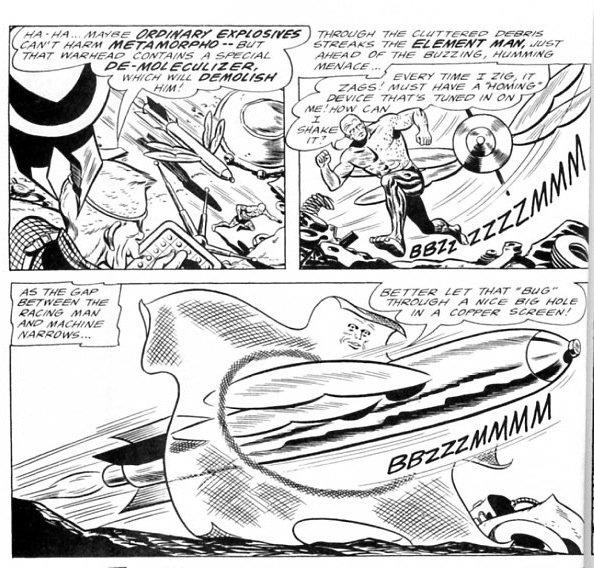

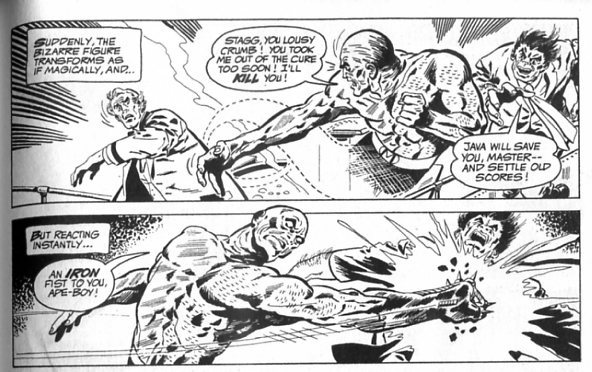

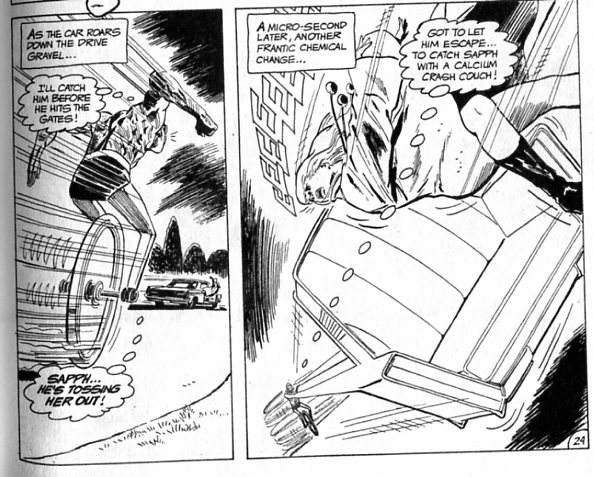

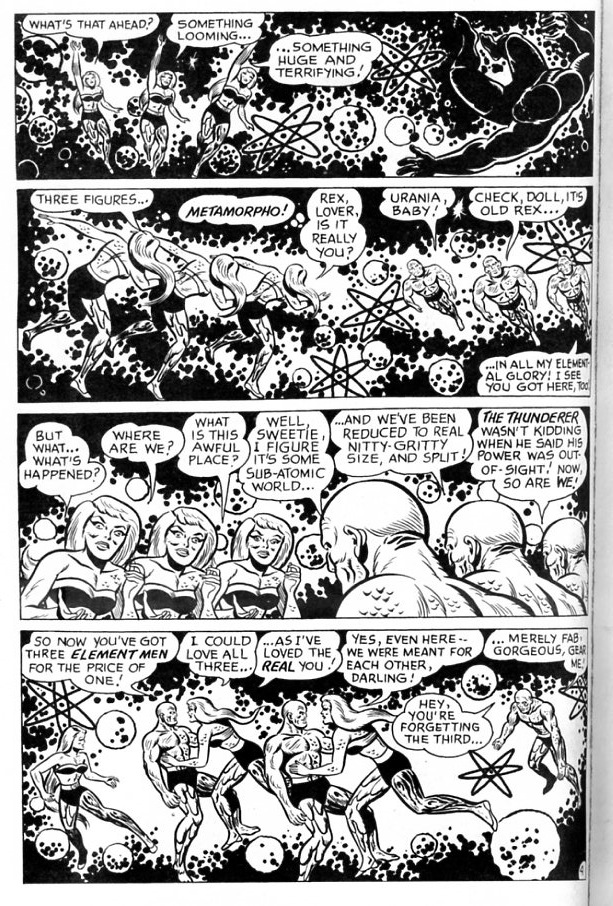

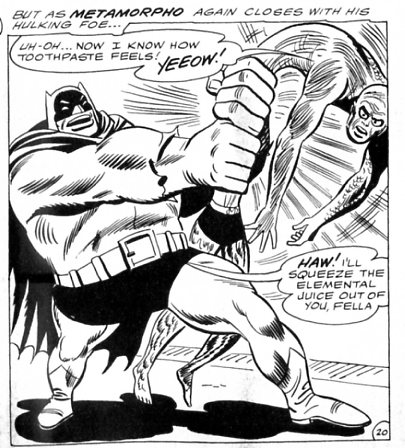

The article itself was written and illustrated so quickly, so impulsively, that the reaction to it seemed impossibly outsized, exaggerated. In particular, my confidence in my own illustration skills was tenuous enough that I felt a certain pain at their exposure, despite the delight I had taken in the few brief hours of their creation.

The speed at which everything moved was its own kind of hazard. In a few strange, bewildering weeks I went from a mostly unpaid comics blog contributor and unpublished cartoonist, to a writer/illustrator with a smart, sympathetic agent, a publisher, and a book deal. The transition and all of the ensuing attention was a heady experience, but the comedown, when it finally arrived, was harsh.

In short, I found it very difficult to draw anymore.

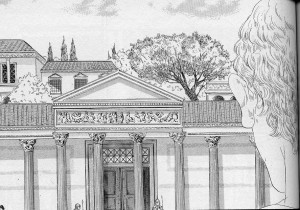

Because of the amount and nature of the links to the article, the exact numbers are hard to arrive at, but let me just skip over the particulars and say that it is very likely that more people have seen my drawing of Omar walking down a narrow Bodymore street than will see or hear anything else that I will ever create in my life. A set of drawings I created in the span of a few hours, drawings that reflect both my strengths as an illustrator (pastiche, virtuoso ink technique) and my weaknesses (virtually everything else), will most likely be, measured in numbers, the most significant thing I’ll ever be part of. This was a slow realization for me, made over a painful few weeks that also happened to contain the break up of my marriage of five years. It was during these weeks of weakness and personal turmoil that I would be required to create about two dozen new illustrations in a similar vein, this time for print, a medium that for me feels as permanent as any ever created. We are, after all, still reading the two-thousand year old garbage of the ancient Egyptians, them having successfully captured their thoughts and feelings and business transactions on papyrus in ink. (“Don’t worry about it,” my friend Shanna told me. “I mean, what percentage of people that read the initial article will even see the book? It’s no biggie, right?”)

It’s interesting to compare today’s fractured, specialized media environment to the vast undivided audiences of the previous century’s newspaper cartoonists. The early newspaper cartoonists had tremendous audiences for their work, audiences that would be unheard of today for any similar form of entertainment. They also had the illusion, though, of impermanence, a kind of impermanence that can nurture a certain kind of risk taking and impulsivity that can be invaluable to someone’s creative development. These early cartoonists worked knowing that, no matter how flat a single installment fell, no matter how many copies made it into print, a week later a hundred thousand copies of a strip would be a few thousand folded on a few thousand night stands and bureau tops. Two weeks after initial publication, how many copies would remain? A month later and anything could be forgotten. Newsprint was the most transitory of mediums, powerful but temporary, a bright flare turning in a flash to chalk message scrawled on the sidewalk.

Up until March I’d actually felt this way about virtually everything I’d written for public consumption, which amounted to an article a month at HU and a handful of articles and interviews for the Comics Journal. All of these brief works could be changed, edited if the need arose, always the possibility of elimination or correction. But even if I had wanted to do so, there was no way possible to put Victorian Omar back in the bottle. He now wandered this Wired world on his own power, untethered from the tongue in cheek piece of criticism that spawned him.

As for the actual problem of drawing all those illustrations through my own insecurity, I was greatly helped in this task by that old friend of the newspaper strip cartoonists—the regular deadline. Having five weeks to complete thirty illustrations and my portion of the text, I was forced to set concrete, daily completion goals, and these goals enabled me to power through my restlessness and difficulty and actually complete the drawings required. If I hadn’t had such a hard (and, now, seemingly arbitrary) deadline, I have no doubt that I would still be fussing with the details of the illustrations, re-imagining and re-evaluating, redrawing, planning…anything to avoid that dreaded sense of disappointed completion.

Finishing the book, however, didn’t make my desire to draw come back, nor did my eventual satisfaction with the illustrations. Something inside me seemed to have been switched off, some key part of me that was capable of self-satisfaction and confidence. I wondered if I would ever draw again on my own impetus.

Months went by. I drew, always through necessity or obligation. Illustrations for friends’ wedding invitations, contributions to round tables or one-off art shows, fulfilling promises made before my great freeze. But about a month ago, something changed again, something that seemed unrelated to drawing at the time. I met an extremely skilled fiddle player at a party of a mutual acquaintance, and after briefly getting to know each other, she invited me to busk with her at the local market. We had our first rehearsal on a Sunday afternoon in her backyard, putting together ten songs in about an hour and a half. We were performing the next day.

Busking, it seems, was the cure for my debilitation. When you’re playing in public, train wreck or triumph are equally fleeting, both erased minutes after the moment is over. No safety net, but no lasting impression, no pressure to be worth it; to be worth the lives of the trees that died to bring your drawings to life, to be worth the twenty dollars someone impulsively plunked down for your strange piece of cultural critical pastiche. In short, no pressure at all.

It’s not just the transitory nature of the performance that’s so appealing—it’s also the immediacy, and literal representation of the audience’s reaction. Joy and I worked all of May to write and illustrate a book that won’t be read by its intended audience for several months still. Even this informal blog post was composed over the course of a few days, and any reaction to it will necessarily follow that period of composition. How can this compare to the instant feedback, and judgment, of a crowd? When Rachel and I play at the market, we know when someone’s not interested, or actively dislikes what we’re playing–they pass right by. Someone that’s enjoying themselves stays, listens, puts money in our case or buys a CD. There’s a kind of cleanliness to it, art or entertainment made transactional again, unabashedly so, no confusion of role or purpose. We place Rachel’s fiddle case in front of us, open, as we play, a little bit of seed money at the bottom to function as change, grey-green on faded red velvet. In some ways, it’s the promise of those utopian Internet prognosticators of last decade made flesh–a perfect meritocracy where the best survive and thrive and the rest go home with empty cases. I grasp, stab at a comics comparison, desperate for justification for this article’s existence– witness the meteoric rise of Kate Beaton, which seems to be due solely to her making some really, really funny comics.

But of course, it’s not as simple as that–it’s not necessarily the best players that succeed, but the flashiest, the loudest, those most suited to the noise and bustle of the environment. One of the best buskers in the market, a man famous in Seattle while remaining virtually unknown by name, isn’t known for his unarguably charming songs, but because he has the unusual ability to hula hoop while playing the guitar, singing, playing percussion with his feet and balancing a second guitar on his chin. The parallel holds–the main breakout successes in web comics have primarily been gag strips, short punchy and easily digestible, able with sheer volume and verve to cut through the noise of the crowded environment.

When we are actually playing, though, the mechanics of the act itself, the social analogies and all the other possibilities, are the last thing on my mind. Virtually all of my attention is occupied by the moment, in sharing music and time with a person I am delighted by, and sharing that happiness with the people around us. And maybe this is ultimately what had been missing for me from drawing–creation without obligation, a sensual engagement with the world, the glorious moment of sticking your face in the dirt and remembering that you’re alive and doing the things that you want to be doing solely because it is what you desire. I might get tired of busking in a month or two–I might keep doing it for years. But either way, I know for sure that when it feels like an obligation, it will be time to change things again.

I’ve been sketching again, in brush, bolder and quicker than I’ve worked in the past. I don’t know if anything will come of it, and I don’t seem to care if it does.

Addendum-I filled Rachel in on the general premise of this article a few days ago, and she had a good laugh. “You can think about it being that way if you want,” she told me, “but it isn’t temporary like you’re describing. You just think that because you haven’t being doing it very long.” Video cameras and phones are everywhere, she explained. People are filming us all of the time. People take our picture hundreds of times a day. We don’t have any way of knowing where or when any of those things will show up.

She continued. “If you Google my full name one of the first things that shows up is this stupid article about the Seattle busking program that appeared in a million different places.” She can’t escape it, she says, nor the photo depicting her and another busker in an awkward high-five.

Me? I’m still choosing ignorance, and the gratification of the moment. It seems like the only sound strategy available.