I spent last week at my brother’s. While my son frolicked with his cousins, I raided my sibling’s library. So here’s a series of brief reviews:

Barefoot Gen, Volume 1 by Keiji Nakazawa A story of world-historical import and great human tragedy is always improved by warmed-over melodrama, poignant irony, and random fisticuffs. Stirring speeches about the horrors of war are feelingly juxtaposed with scenes of anti-militarist dad beating the tar out of his air-force-volunteer son. On the plus side, though, drill-sergeant brutality set pieces are apparently the same the world over. Also, to give him his due, Keiji Nakazawa stops having his characters beat each other up for no reason every third panel once the bomb drops. Tens of thousands of civilians running about shrieking as their flesh melts is enough violence for even the most impassioned pacifist adventure-serialist. It’s okay to have Gen rescue the evil pro-war neighbors from their collapsed house and to have the evil pro-war neighbors refuse to help dig out Gen’s family and to have the sainted Korean neighbor help carry Gen’s mom to safety as long as you don’t have Gen and the Korean pummel the evil pro-war neighbors with a series of flying kicks as the city burns. It’s all about restraint.

Barefoot Gen, Volume 1 by Keiji Nakazawa A story of world-historical import and great human tragedy is always improved by warmed-over melodrama, poignant irony, and random fisticuffs. Stirring speeches about the horrors of war are feelingly juxtaposed with scenes of anti-militarist dad beating the tar out of his air-force-volunteer son. On the plus side, though, drill-sergeant brutality set pieces are apparently the same the world over. Also, to give him his due, Keiji Nakazawa stops having his characters beat each other up for no reason every third panel once the bomb drops. Tens of thousands of civilians running about shrieking as their flesh melts is enough violence for even the most impassioned pacifist adventure-serialist. It’s okay to have Gen rescue the evil pro-war neighbors from their collapsed house and to have the evil pro-war neighbors refuse to help dig out Gen’s family and to have the sainted Korean neighbor help carry Gen’s mom to safety as long as you don’t have Gen and the Korean pummel the evil pro-war neighbors with a series of flying kicks as the city burns. It’s all about restraint.

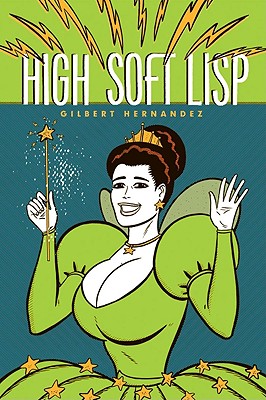

High Soft Lisp by Gilbert Hernandez

High Soft Lisp by Gilbert Hernandez

Hernandez tells us several times over the course of this searingly human graphic novel that his protagonist, Fritz, has a genius level IQ. And how would we know if he didn’t tell us? Also, she was probably sexually-abused as a child, and therefore the fact that she fucks anything that isn’t nailed down is a sign of her profound psychological thingy, and not a sign that Hernandez likes to draw balloon-titted doodles fucking everything that isn’t nailed down. In this, of course, the comic is profoundly different from past works like Human Diastrophism, in which there were big tits and gratuitous fucking, but interspersed with paeans to the human interconnection of all of us who are bound together by empathy and profound meaningfulness and also by a love of big tits and gratuitous fucking.

Whoa Nellie! by Jaime Hernandez If you adore female Mexican wrestling and girls’ fiction about the ups and downs of friendship — then I still can’t really see why you’d want to read this.

But, you know, it’s “fun” and “enthusiastic”. “Buy it now.”

Ghost of Hoppers by Jaime Hernandez Alternachicks drift through their alterna-lives with quirky poignance and poignant quirkiness. Plus, bisexuality.

To be fair, to really understand the subtle characterizations here, you need to take the entire Hopey/Maggie saga and inject it into your eyelids weekdays 8:30 to 5:30 and weekends 12-6. Only when you’re blind and destitute and wretching blood in the sewer with the ineradicable taste of staples glutting your tonsils will you truly understand the blinding genius of layered nostalgia.

Cool It by Bjorn Lomborg Better than the movie Lomborg argues convincingly that it would be better to cure malaria and HIV than to wreck our economies by failing to reduce greenhouse emissions. Which largely confirms my suspicion that global warming is less a real policy priority than it is an apocalyptic fad — a rapture for Prius-owners.

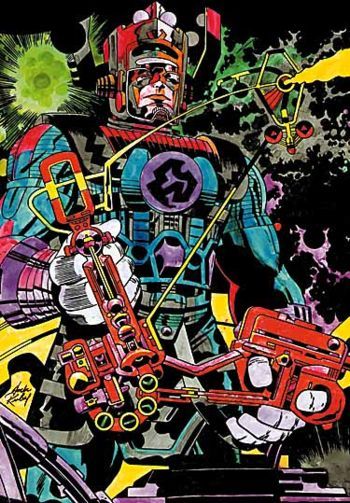

Marvel Masterworks: Jack Kirby There’s been a lot of debate in comments here as to whose prose is more tolerable, Stan Lee’s or Jack Kirby’s. After trying and failing to read the Marvel Masterworks volume, I think I have to say, who gives a shit? Lee’s hyperbolic melodrama is slicker and Kirby’s more thudding, but the truth is that if you put the two of them together in a room with an infinite number of monkeys and a typewriter and gave them all of eternity you’d end up with a pile of monkey droppings and a lot of subliterate drivel. The ideal Jack Kirby would be a collection of his illustrations of giant machines and ridiculous monsters and weird patterned backgrounds with all the dialogue balloons excised. Short of that, you look at the pretty pictures and you try your best to skip the text.

Captain Britain by Alan Moore and Alan Davis It’s hard to believe anyone was willing to publish such an obvious Grant Morrison rip off, but I guess comics are shameless like that. It’s all here with numbing inevitability — the multiple iterations of our hero (Captain U.K. of earth 360b, Captain Albion of earth 132, etc. etc.), the goofily foppish reality altering villain, the cyberpunky organic/computer monster. Throw in a standard kill-all-the-superheroes plot and a bunch of high-concept powers (abstract bodies! summoning selves from further up the timeline!), add some borderline-satire of the square-jawed protagonist and you’ve got everything Morrison’s written for the last two decades. To be fair, though, Moore and Davis seem to be on top of their derivative hackitude, and as a result there’s none of the pomposity that can infect their prototype. Captain Britain doesn’t die for our sins and he isn’t an invincible icon; he’s just some dude in spandex swooping through the borrowed plot with equal parts bewilderment and bluster. Sometimes imitation works better than the real thing; maybe Morrison should try ripping off these guys next time.

The Defense by Vladimir Nabokov Nabokov’s characters sometimes seem more like chess pieces than like people; Nabokov pushes them here and pushes them there about the page, forming patterns for his own amusement. There’s no doubt that it is amusing, though, and while I don’t pretend to understand all the ins and outs of the game, I enjoyed watching the patterns expand and dilate, moving in black and white through their silent hermetic dance. There’s one passage, which I wanted to copy out but now can’t find again, in which our protagonist, the corpulent, hazy chess master Luzhin, types a string of random phrases at the typewriter and then mails them to a random address from the phonebook. If any book makes me laugh that hard even once, I consider myself well-recompensed for my time.

The Real the True and the Told by Eric Berlatsky Eric printed an excerpt of his book on HU here, but I hadn’t gotten a chance to read the whole thing till now. Despite his daughters’ review (“Why are you reading Daddy’s boring book?”) I really enjoyed it. The basic thesis is that post-modern texts like Graham Swift’s “Waterland” or Rushdie’s “Midnight’s Children” don’t actually deny the reality of history. That is, history in such works is not just text. Rather, postmodern lit tries to approach the real through non-narrative means. The emphasis on the textuality and artificiality of historical narratives is a way of reaching through those narratives to reality, not a way of denying the existence of reality altogether. Basically, for Eric, post-modern fiction rejects, not reality, but simplistic narrative, suggesting that the first can only be accessed by rejecting or resisting the second.

I think it’s a convincing argument about the goals of post-modern fiction, though I question whether the tactic is as successful as Eric seems (?) to want it to be. There are two problems I see.

First, as Eric’s book kind of demonstrates, the anti-narratives and non-narratives Eric discusses are themselves, at this point, narrative tropes. When Artie in Maus laments the insufficiency of narrative, for example, he’s voicing long-standing clichés intrinsic to accounts of the Holocaust; when Kundera talks about Communists rewriting history, he’s voicing long-standing clichés about totalitarian regimes which go back to Orwell, at least, and probably before him. Self-reflexive, alternative narrative structures are their own genre at this point…they’re well-established narrative traditions in their own right. It’s hard for me to see, therefore, how those narrative traditions really effectively escape their tropeness and encounter the real in a way that’s diametrically opposed to the way that more traditional narratives encounter the real. Which is to say, Eric’s argument seems to be that the Book of Laughter and Forgetting is through its form closer to the real than Pride and Prejudice — and I don’t buy that.

The second problem I have is that the real in many of these books (and in Eric’s discussion) ends up being linked to trauma. The Holocaust and pain and suffering is more “real” than love or marriage. Eric also notes that the quotidian, or unnarrataeable is often figured as the real too…which would mean that the real is either trauma or boredom. I’m as pessimistic as the next Berlatsky I think, but I’m not really sure why bad or neutral is more real than good.

Which brings me to my second second (and last) problem…which is that I think it’s quite difficult to theorize the real without theorizing the real. Or to put it another way, can you talk about the real while bracketing theology? If you’re at a place where the real is either the Holocaust or tedium, it’s hard to see how exactly that’s different in kind from nihilism — and if you’re a nihilist, what are you doing talking about the real in the first place?

Anyway, the book was great fun to argue with, and probably the thing I read on vacation that I most enjoyed. It’s amazon page is here in case you want to raise the fortunes of the extended Berlatsky family.

Makes you wonder who was watching Noah’s kid while he did all of that reading?

Uh, Noah? You realize that Moore and Davis’ Captain Britain came out before Morrison even started his comics career? (Ok, his very early comics may have overlapped with the end of their run.) I guess you didn’t. That kind of know-nothing knee-jerk reaction pretty much sets the tone for the rest of this post. It’s the kind of column that makes me want to delete HU from my bookmarks and never have anything to do with it again. It really undoes a lot of the credit that your more thoughtful posts accrued. It’s really a pity.

Yes, I know Moore came first. It’s a joke.

And I think it’s pretty important to torpedo my reputation on occasion. Don’t want to get too stuffy, after all.

Noah doesn’t read, he sits in the back and makes farting noises.

Okay, now you’re just trying to flatter me.

Noah–if you want people to get that it’s a joke, you have to first establish a reputation that you know what you’re talking about.

Nah; I don’t need anyone to get that it’s a joke. I mean, if you got that it was a joke, I’d miss out on your irate response…which I think was also pretty funny.

My dear friend Bert pointed out that disciplinary anxiety seems to be a constant theme on this blog. I guess I just bring it out in folks.

But really, I’m a lover not a fighter. If you don’t like the first half, Andrei, you could talk about my brother’s book and the philosophical status of the real in post-modernism. Surely that’s sufficiently serious?

Oh, and the last sentence of the Capt. Britain discussion is the tell.

I fail to see the disciplinary anxiety in my reply; pointing out that your knee-jerk reactions are superficial and uninformed may simply have to do with your knee-jerk reactions being superficial and uninformed. But if it makes you feel better to think there must be some other cause for my claiming that your knee-jerk reactions are superficial and uninformed, go ahead and tell yourself that.

Andrei, Consider that Noah likes to skip over the boring parts of Proust looking for the good parts. This gives him time to dip pig- tails in inkwells.

But they’re not uninformed; I knew the thing that you thought I didn’t know. So…what’s you’re problem, exactly?

Your response when I say, “this isn’t very good for this reason and that reason,” is to say, “hey! You don’t know enough to say that!” But my knowledge or lack thereof has nothing to do with whether or not what I say is correct. Freaking out about whether or not so and so has the credentials to say such and such is definition status anxiety.

And it’s pretty funny to call my knee-jerk reaction superficial and ill-informed when your own knee-jerk reaction was based entirely on a clumsy superficial reading which left you looking kind of ridiculous. You could have just shrugged and said, “whoops, made a mistake” — but instead you double down. It’s almost as if your shirt is so stuffed you can’t even breathe in there, Andre.

And, you know…we could still talk about the real and postmodernism. Or we could continue to exchange juvenile insults. Whatever works for you.

Holly, you’ve got me confused with Robert. You need to read more closely!

Noah, your responses to Jaime, Gilbert, and Kirby were just as superficial and uninformed, and as far as I can tell you don’t have the out of claiming they were jokes too. I did say it “sets the tone for the rest of the post.” It’s not about credentials, it’s about your inability to read them to a depth of more than one millimeter. But if you think it’s about credentials, again, whatever makes you sleep better at night.

It’s funny that you think I’d approve instead of a more “serious” conversation about the real and postmodernism. Yawn.

Uh…okay. I’m interested in the real and postmodernism, and my brother’s book had a lot of thoughtful things to say on those topics…but whatever. I guess you’re just in reflexive sneering mode now; I know that that can be hard to break out of.

So why exactly is my reaction to Gilbert uninformed, as an example? Do you feel High Soft Lisp is a work of great humanity and moral genius? You’re arguing it’s not intended to be a stroke book? Or you’re claiming Kirby’s prose is deathless and his plotting immaculate? If you want to argue those points, go ahead, but if you’re just going to throw insults, I’m going to conclude that you’re a fanboy who uses his academic credentials to shield his shoddy taste and crippling nostalgia.

At what point in this discussion did I ever mention any academic credentials? It’s funny how you feel you need to bring them up just to dismiss my comments. I have nothing to say in defense of High Soft Lisp (haven’t read it, your position on it seems defensible), but your takes on Gilbert’s earlier work, on Jaime and on Kirby are just, again, really superficial, much more reminiscent of back-of-the-comic-store fanboy talk than anything I wrote. And now you’re resorting to cliched, one-size-fits-all retorts (“Stuffed shirt”? “Crippling nostalgia”?). I wouldn’t have thought your rhetorical arsenal, or for that matter the sense of humor you usually try to put on when answering negative criticism, would have run out so early.

Noah, I agree with you on most of those comics (the ones I’ve read at least) except Ghost of Hoppers. Maybe you do have to have read earlier parts of the series to appreciate it, but… that’s the way most of Jaime’s work is. It’s like reading the second book of a trilogy and skipping the first and third.

“Whoa Nellie”, though, is pretty much a trifle. Though it has some nice formal elements to it: http://madinkbeard.com/archives/whoa-nellie

Sorry, You Watchmen guys are hard to tell apart.

Hey, Noah — Regarding the Marvel stuff, if you can dismiss it out of hand so easily, I think you might just be a tad too close to the source material.

Whenever possible, I try and look at things from a wider, historical point of view. In the realm of comics, it would be easy for a classical snob to dismiss every comic strip or comic book ever made as mass-produced literary detritus — even material that has garnered widespread critical acclaim amongst comics historians.

If you think about it, however, contemporary or near contemporary critics are often much harder on a creator than those of later generations.

For example, Samuel Pepys called one of Shakespeare’s plays “insipid” in his famous diary. Goethe said of Durer’s work, “Ugly shapes and extravagant fancies have interfered with his incomparable talent.” The latter almost sounds a bit of “Hooded Utilitarian” criticisms of Frazetta, doesn’t it?

The Marvel Silver Age material, while not Shakespeare or Durer, has undeniably had a HUGE impact on 20th and 21st Century culture. For you to dismiss it out of hand, without thoroughly exploring the depth and range of that impact, is a pretty piss-poor bit of criticism, don’t you think?

;)

Andrei, all right, all right; you win. Five or so TCJ message board back and forths is all I can really work up the bile for these days. I’m sorry you didn’t like the post…but, you know, there’s always something new tomorrow.

Derik, that seems reasonable about Jaime. I was trying to read Whoa, Nellie because it seemed self-contained…but that didn’t work, obviously. A friend suggested Death of Speedy is a better place to start…maybe I’ll give that a go (the same friend also assured me that there was no way I’d ever like Jaime though…so perhaps it’s a lost cause….)

Holly, that’s because we’re all simultaneous big blue naked avatars of Dr. Manhattan.

By the way, anyone else think that Durer was the first-ever “popular culture” artist?

Hey Russ. I’d say it’s had a moderate-sized impact, rather than a huge one. Marvel’s always been a specialty interest; pretty small beer compared to, say, hip-hop (though still certainly a cultural force.)

And…I didn’t entirely dismiss it. That Galactus drawing kicks ass. I really do like paging through and looking at the pretty pictures with Kirby and (sometimes) Ditko. I just find the writing almost unreadable at this point, whether that writing is by Stan Lee or Kirby himself.

Noah: Death of Speedy is a good starting place. Though… yeah, you probably won’t like it regardless. But, who knows?

Russ:

“By the way, anyone else think that Durer was the first-ever “popular culture” artist?”

Yes, if you consider emperors Maximilian and Charles and other aristocrats to whom he worked popular enough. Or if you consider 15th and 16th centuries humanism as part of the popular culture of the Renaissance.

What about those marvels of early performance art “The Flagellents?”

Domingos — Hmmm, do I detect sarcasm here?

So Durer worked for artistocrats? Big deal! That doesn’t negate his innovative, popular culture-esque approach to printmaking for the masses.

Next you’ll be claiming that Everett Raymond Kinstler, because he later became a portrait painter of presidents, wasn’t really a popular culture artist. Kinstler, by the way, embraces his pop culture roots. Kudos to him!

How many votes did Ars moriendi get in the poll?

The “masses” couldn’t afford a square inch of one of Dürer’s etchings, I’m afraid…

A page from a “Dark Age” Comic Book.

http://dfg-viewer.de/show/?set%5Bimage%5D=7&set%5Bzoom%5D=default&set%5Bdebug%5D=0&set%5Bdouble%5D=0&set%5Bmets%5D=http%3A%2F%2Fmdz10.bib-bvb.de%2F~db%2Fmets%2Fbsb00039962_mets.xml

There were a good number of these “block books” printed in the 1400’s.

Noah — Moderate-sized? Maybe. But you really can’t say for sure, can you? No one has really explored the impact in a scholarly fashion.

From a personal, anecdotal point of view, I’ve been amazed at how many “non-comics” people I’ve met over the years who, when they find out I’m a comic book artist, say something like, “Oh, yeah! I collected Spider-man until I went off to college and my mom threw my comics out.”

Not too long ago, I and a good sports buddy of mine from the 1970s re-connected, via e-mail, after about 30 years. Last month, during one of our e-mail exchanges, he started talking about the Cap film, and then went into a side conversation about Sharon Carter!

Last year I was at a barbecue at my brother’s house, and one of his friends walks up to me and pops open a briefcase full of bagged, mint condition comics he’d saved since the 1970s and said, “Hey, Russ! Check these out!”

A while back, while discussing some current films over the phone with producer, I mentioned I was a comic book fan. The next thing I knew, we went down a 10-minute comic book collecting rathole.

A Marine I know found out I was a comics buff and started recommending graphic novels for me to read, such as “Scalped.”

This happens ALL THE TIME!

It’s like tens of millions of comics fans are members of some massive Mason-like organization, and the secret code word for a fellow brother or sister is, “I read comic books.”

holly cita:

“A page from a “Dark Age” Comic Book.

There were a good number of these “block books” printed in the 1400?s.”

None of these are top ten material though. It seems that _Calvin & Hobbes_ is a lot better…

Sure, there’s a fairly large number of men and a much smaller number of women who care about Marvel comic books. It’s just nothing like the number of people who care about hip hop, though…or the number of people who care about the Wire.

It’s easy to tell that this is true from looking at my site stats. It wasn’t an article about spider-man that got 100,000 plus hits, I can assure you.

Stuff like Harry Potter and Twilight are just enormous pop culture phenomena. Comics used to have that kind of reach back in the 40s, I think, but it was long vanished by the 60s when Marvel was up and running. Again, that doesn’t mean it had no impact; it obviously had some, and continues to have some. But I think it’s of the nature of things that folks who are really into comics tend to overestimate their influence.

And I like Jack Kirby a good bit more than I like Harry Potter…and probably somewhat more than I like Twilight.

Hey, don’t put it on me, Domingos. I voted for Hokusai.

Holly, there’s something screwy when I try to follow that link. Is there a problem on your end or is it maybe my browser?

Domingos wrote: “The “masses” couldn’t afford a square inch of one of Dürer’s etchings, I’m afraid…”

Maybe not now, but during his Nuremberg years, Durer made a considerable number of prints of each one of his works, and those were sold by him and through an agent. As a matter of fact, it was the circulation of all of these prints that made him famous throughout Europe, and is what probably led to his gigs with Maximilian and other aristocrats.

By the way, though this has nothing to do with Durer, I had a relative who was once the mayor of Nuremberg.

Works for me.

Is this any better?

http://dfg-viewer.de/show/?set%5Bmets%5D=http%3A%2F%2Fmdz10.bib-bvb.de%2F%7Edb%2Fmets%2Fbsb00039963_mets.xml

If not try cutting and pasting the link into your browser.

Since these are wood block printed there are many “blank pages.”

http://dfg-viewer.de/show/?set%5Bmets%5D=http%3A%2F%2Fmdz10.bib-bvb.de%2F%7Edb%2Fmets%2Fbsb00039963_mets.xml

http://dfg-viewer.de/show/?set%5Bimage%5D=8&set%5Bzoom%5D=default&set%5Bdebug%5D=0&set%5Bdouble%5D=0&set%5Bmets%5D=http%3A%2F%2Fmdz10.bib-bvb.de%2F~db%2Fmets%2Fbsb00039963_mets.xmlhttp://dfg-viewer.de/show/?set%5Bimage%5D=9&set%5Bzoom%5D=default&set%5Bdebug%5D=0&set%5Bdouble%5D=0&set%5Bmets%5D=http%3A%2F%2Fmdz10.bib-bvb.de%2F~db%2Fmets%2Fbsb00039963_mets.xml

Yes, that worked. Thanks!

Noah wrote: “But I think it’s of the nature of things that folks who are really into comics tend to overestimate their influence.”

Perhaps.

But Marvel Silver Age characters have shown remarkable staying power — nearly 50 years and counting, in many cases. In addition, their reach went far beyond comic books, touching almost every popular culture medium imaginable.

Think about some of the pop culture icons of the past that, say, most Americans under the age of 30 have probably never heard of. Ed Sullivan, for example. Or the Hula Hoop. Or Walter Cronkite. Closer to home, even stuff like Pogo, Li’l Abner, or Steve Canyon would bring quizzical looks from the average under-30 person. Hell, ask anyone under the age of 50 what a Shmoo is and all you’ll get is a blank look. Yet, in 1949, Shmoos were all the rage.

So, I suspect Marvel characters might be more ingrained in our culture than you may think.

Russ:

We must be meaning different things when we use the word “masses.” I use the quotation marks because talking about 15th and 16th century masses is kind of an anachronism. Besides, Durer’s Humanism couldn’t be perceived by the “masses.” The people had their own rich culture back then. Unfortunately all that is lost by now (or changed to become meaningless folklore).

While Marvel Comics might be small potatoes as a cultural force, I’d suggest that the North American Superhero Aesthetic (which Kirby played a major role in inventing) has had a profound impact on our visual landscape. Car ads, movies, whatever. Kinda’ stating the obvious, I know.

BTW, I am stoked to check out Eric’s book. I’m reading a lot of documentary theory right now, which has been concerned with the status of the real for some time now. A literary perspective will be a breath of fresh air.

Hey, if I sell a copy of Eric’s book, I feel my nepotistic work is done.

It is really good, actually…and yeah, I think it would definitely have something to say to documentary theory. That makes sense.

I’d agree that the well known superheroes (superman, batman, spider-man, wonder woman sort of) as a unified group are definitely a cultural touchstone of sorts. But…it’s still not as big a deal as something like hip hop, I’d argue, and it’s also fairly diffuse. It’s definitely not tied strongly to the original incarnations or creators. It’s just hard for me to go from “Lots of people have a general idea of who superman is” to “Jack Kirby is a cultural figure of immense importance.”

In some way the whole conversation is beside the point anyway, since I don’t think that cultural cache really has anything to do with quality. Even if Jack Kirby was the most popular artist in the history of humankind, I’d still find his writing unreadable. (And I’d still enjoy looking at his drawings.)

Does anyone want to stand up for Barefoot Gen? I take it Andrei hasn’t read that one, and/or doesn’t care….

Domingos — I suspect you’re right. My opinion about “popular culture” is probably more inclusive than yours. I would lump Shakespeare and Durer together as popular culture creators of their day, but I’m sure Shakespeare’s audiences were much more economically diverse. After all, a performance at the Globe Theatre cost a penny a person (about $1.50 today), while Durer’s prints no doubt targeted the upper middle class and the wealthy.

Still, we ARE talking about mass audiences in both cases.

Noah — Per my earlier point, the musical genre of hip hop may be a musical footnote in 50 years. Marvel characters have had proven staying power, and will not disappear from the cultural ether any time soon.

The Captain Britain capsule review made me spit water all over my keyboard. Fine work, sir.

Hip hop has been around for probably 30 years, depending on how you count it. It started out as a subcultural phenomena, like Marvel…but then it took over the world.

So basically, hip hop has been around for the majority of the time that Marvel superheroes have been around. The main difference is that it’s much, much, much, much more popular and influential. It’s a lot (a lot) more credible to suggest that marvel superheroes will have vanished in 50 years than it is to suggest that hip hop will have.

Sean, I’m glad somebody got it. I hope your computer’s okay!

I laughed at the Captain Britain thing, too.

The one thing it was missing, tho’, was contrasting and massively under-motivated praise for an obviously shithouse artist. Something like “of course, neither Moore nor Morrison can hold a candle to Gerry Conway”… Try harder next time, Noah!

Noah wrote: “Hip hop has been around for probably 30 years, depending on how you count it. It started out as a subcultural phenomena, like Marvel…but then it took over the world.”

Yeah, 30-odd years sounds about right. As a matter of fact, I have Rapper’s Delight (1979) on my iPod playlist — one of the songs that helped start it all. Personally and objectively, I don’t like a lot of the new stuff, though, despite the fact that my tastes are (and have always been) eclectic.

Hip hop sales have nose-dived during the past five years. This could be because of the economy; or because of illegal file sharing; or because a lot of the newer stuff is stale, crude and uninspired; or all three. We’ll just have to see.

One other thing… despite your insistance that hip hop is so popular, the Marvel stuff crosses three or four generations. Hip hip might cross one, or on a good day, maybe two generations. Quite a few people in their 60s, 70s and 80s know who Spider-Man is, but probably couldn’t name even one hip hop artist if their life depended on it.

I think Noah’s downplaying Marvel’s impact on the popular-culture, particularly with regard to Spider-Man. I don’t think there’s a person alive in North America, or frankly the developed world, who isn’t aware of the character to some degree. The property’s presence, particularly over the last decade, has been enormous. The three Raimi films are among the top 100 N.A. moneymakers after being adjusted for inflation, and the first two are among the top-ten box-office champs of the last decade. Spider-Man is a much bigger deal than Twilight in pop-culture terms. It’s a bigger deal than Harry Potter as far as movies go, and the only reason I wouldn’t say it’s bigger in terms of the culture is that it hasn’t enjoyed comparable success in publishing.

To say it hasn’t enjoyed the same success in publishing is something of an understatement. I looked at figures at one point, and as far as I can tell, the Harry Potter books have sold better not just than spider man, but than all graphic novels combined.

———————

Noah Berlatsky says:

Yes, I know Moore came first. It’s a joke.

———————

I had no trouble “getting” the joke, for what it’s worth. Taking it for granted that the Moore/Davis Captain Britain stuff surely dated from their “2000 AD” days helped…

———————-

The second problem I have is that the real in many of these books (and in Eric’s discussion) ends up being linked to trauma. The Holocaust and pain and suffering is more “real” than love or marriage…

———————–

Maybe it’s easier to consider those more “real” because they’re, in a sense, simpler events/experiences? The Holocaust was an elaborate endeavor, yet just a method aimed at exterminating undesirables. Can love or marriage be described as aiming at such uncomplicated physical ends?

As for “pain and suffering,” a kick in the ‘nads certainly feels more intensely real than the muddled and ever-mutating phenomenon of “love,” and creates obvious (sometimes permanent!) physical side-effects…

———————-

…Does anyone want to stand up for Barefoot Gen?….

—————————-

Keiji Nakazawa has told his story in many forms; the only one I’ve read was the one-shot “I Saw It” ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Saw_It ). While I can understand those who’d consider its manga-style cartoonishness as inappropriate, it nonetheless is informative and affecting, vividly conveying experiences of the inhabitants of wartime Japan.

Been decades since my last reading, but can vividly recall scenes such as Keiji and his brother gnawing on hunks of wood to try and assuage their hunger pangs; Keiji and a neighbor spotting the glint, high in the sky, of the fateful B-29 that would bomb their city; the chilling fact that only the happenstance of standing behind a piece of wall at the moment of detonation saved him; his horror at regaining consciousness and seeing that “everyone has been turned into monsters!”, their skin melted from their flesh; these same survivors then trudging along painfully, their sloughed-off skin dragging on the ground; a husband trying futilely to rescue his wife, trapped in the burning rubble of a collapsed house; how bodies, being disposed of in mass cremations, would curl up like shrimp on a grill…

Perhaps the necessary brevity of “I Saw It” made for a more documentary-like approach, avoided editorializing and pitfalls such as Noah complained of: “…It’s okay to have Gen rescue the evil pro-war neighbors from their collapsed house and to have the evil pro-war neighbors refuse to help dig out Gen’s family and to have the sainted Korean neighbor help carry Gen’s mom to safety…”

It’s better than you’re portraying it. Spider-Man’s publishing history also has to include periodical sales that date all the way back to 1962. From 1963 on, the annual international unit sales have to have been consistently in the millions. And I’m not counting the sales of the newspapers that have published the daily strip, which would really explode the numbers. The Harry Potter publications have probably made more money, but that’s at least in part because the price point is considerably higher. I’m pretty sure that cumulatively more individual customers have bought a copy of a Spider-Man publication over time than have bought a Harry Potter one.

Well, here’s google trends data of harry potter vs. spider-man. It isn’t pretty for spider-man:

http://www.google.com/trends?q=%22harry+potter%22%2C+%22spider-man%22&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=0

Even if you add in spider man without the hyphen:

http://www.google.com/trends?q=%22harry+potter%22%2C+%22spider-man%22&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=0

The web at least thinks harry potter is a lot more important.

I think pain feels more real, though, because we’ve decided it feels more real. The feeling of what is “real” — with or without quotes — is surely a cultural one. Love isn’t less real than pain in any objective sense, right? Both are part of the world; we experience both.

I can see a shorter more documentary approach working better for Barefoot Gen. He’s got a good story to tell; the closer he sticks to it the better off he could be.

Sorry; these are fun to play with. Here’s harry potter vs. spider man no quotes:

http://www.google.com/trends?q=harry+potter%2C+spider+man&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=0

Looks even uglier.

Here’s twilight vs. spider man.

http://www.google.com/trends?q=twilight%2C+spider+man&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=0

You can see the blips for the spider-man movies more clearly there…still nothing like the twilight numbers when that really gets going.

And, ouch, check out Naruto vs. spider man. At least spider man beats dora the explorer…barely.

http://www.google.com/trends?q=naruto%2C+spider+man&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=0

——————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

I think pain feels more real, though, because we’ve decided it feels more real. The feeling of what is “real” — with or without quotes — is surely a cultural one. Love isn’t less real than pain in any objective sense, right?…

———————

Certainly an attenuated emotion like mild embarrassment is as real as cancer; yet physical pain has a more intense effect; we feel it all the way down to our “lizard brain”!

As an example, there’s Joe Sacco’s autobio “How I Loved the War” story of how his injured tooth became much more important to him than the lead-up to the Gulf War, for all his dismay about that oncoming conflict, being surrounded by fellow antiwar folk…

It’s one of those “in-jokes” which only other super hero fans can understand.

Well…Andrei’s a superhero fan and he didn’t get it. So maybe superhero fandom is necessary but not sufficient.

Well, movies are still the best individual measure of pop-culture success. In this case all three have had phenomenally popular film series, so you can’t say any of them have been handicapped on that front. Actually, while Harry Potter movies on average have been bested by the Spider-Man films in North America, the opposite is true internationally. Spider-Man still beats Twilight in both arenas, though.

Is movie success really better than google search terms for measuring pop culture reach? I think those google trend graphs are pretty telling….

Noah:

” think pain feels more real, though, because we’ve decided it feels more real. The feeling of what is “real” — with or without quotes — is surely a cultural one. Love isn’t less real than pain in any objective sense, right? Both are part of the world; we experience both.”

That’s surely true, but there’s a lot more pain in the world than love (we all die, no less). Even love can lead to a lot of pain (if it’s unrequited; if we’re separated from those we love; if those we love die). An artist must be incredibly good to just show the good face of love. Two things may happen if the artist is that bold: (1) the work is very good formally speaking or something (I have no idea, I’m not that good!); (2) it’s saccharine (which happens 99,9 % of the times).

Besides, everybody knows that hapopiness has no story to tell…

Besides, everybody knows that happiness has no story to tell…

You have to separate the films, and their gigantic marketing blitz, from the old source.

Comic books have not been a significant part of popular culture since the 1950’s. They aren’t popular, and large numbers of people don’t read them.

Even these hugely popular movies are something like soap bubbles aren’t they?

They show up all inflated, pop and vanish without a trace. I’m not around comics people, do folks really discuss these movies in the workplace or at PTA meetings? When the big money action flicks run their course very few people will remember them.

He he: “hapopiness” is a great word for pop pap, cuteness and saccharine :D

Pain vs. love. Love is more popular.

I think you have to defend using pain in fiction. Horror is never held in the same esteem as drama. People don’t tend to ask, “why do you want to explore love?” Torture creates more controversy than romance.

link doesn’t work. here it is:

http://www.google.com/trends?q=pain%2C+love&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=0

Domingos…sure, but there’s more tin in the world than gold. That doesn’t make gold less real. Just more expensive.

torture vs. romance:

http://www.google.com/trends?q=torture%2C+romance&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=1

I don’t disagree with you Noah (that’s where I started, saying “That’s surely true”). A work of art is a microcosm. The best microcosms are kaleidoscopic in nature.

Charles:

From Harlequin novels to Bollywood and Hollywood, cuteness, pap, saccharine, kitsch, made fortunes, that’s for sure.

I agree with RSM about Spider-Man’s ubiquity. Maybe people don’t google him so much cause they already know all they need to.

I don’t think that really washes. People don’t know who harry potter is at this point? Come on.

People just aren’t as interested in reading about spider-man or buying spider-man products as they are in reading about harry potter or buying harry potter products. They are less interested in spider man by several orders of magnitude, as a matter of fact.

Here’s some older pop culture comparisons.

Beatles/spider-man: http://www.google.com/trends?q=beatles%2C+spider+man%2C+narnia&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=1

Narnia/Spider-man: http://www.google.com/trends?q=narnia%2C+spider+man&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=1

Beatles are way more of a current cultural force, except for right around the spider-man movies. Narnia and spider-man are comparable, though Narnia still wins (somewhat to my surprise.)

And superman/spider-man: http://www.google.com/trends?q=superman%2C+spider+man&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=1

Supes wins…and I think he’d beat Narnia too (though not the Beatles.)

Shakespeare vs. spider man: http://www.google.com/trends?q=shakespeare%2C+spider+man&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=0

In the Spidey vs Harry sweepstakes, Spidey wins. This is so obvious it shouldn’t even be a subject of discussion;

What does Harry Potter mean to a 60-year-old? Nothing. But that same 60-year-old was only 12 when the first Spidey comic story appeared.

That’s a simple factor of time. Spider-Man has had nearly 5 decades to implant itself into the public consciousness. Look, you can go to Timbuktoo or Vladivostok or Manaus, and I guarantee you’ll come across a Spidey T-shirt, bag, toy or other tchotchke before a Harry Potter one.

Kirby or Lee dialogue: you have to go with the flow on this. Lee’s great contribution was comedy, as full of hilarious schtick as a Borscht Belt tummeler.

Kirby’s “bad” prose, for me, is marvelous almost BECAUSE it’s bad. It’s as though there were these inexpressible concepts bubbling through the strange leaky filter of his conscious mind that had to wrench themselves tortuously onto the page…for me, he’s a bad-good prose and dialogue writer as were Eugene O’Neill (who acknowledged his ‘tin ear’), Theodore Dreiser, or Philip K. Dick…

Actually, in another postthread someone compared Kirby to Blake, in that you really needed to surrender to his exalted daemon to appreciate him — that makes sense to me;

Gen of Hiroshima: admire without liking. To treat the atom-bomb massacre of so many thousands of civilians with the cartoony conventions of manga?

It’s as unthinkable as treating the Holocaust through the lens of a “cat and mouse” cartoon.

I kind of hate to say this…but Maus is a lot better than Barefoot Gen (or at least better than the first volume of Barefoot Gen.) Spiegelman is really a stuffy, serious aesthete; when he uses cartoon tropes, it feels like he’s slumming. But — when you’re dealing with such explosive material, that’s better than not being able to tell that using pulp tropes to deal with massive tragedy is incongruous and problematic. Maus is boring, but it’s not stupid. And stupid is really a problem if you take as your subject one of the 20th centuries emblematic tragedies.

I wouldn’t be so sure that you’d find Spidey before Harry Potter in countries throughout the globe. I believe those google stats are worldwide.

>>>Philip K. Dick>>

Come now. The man sometimes wrote some clunky prose–sometimes writing books from no outlines on amphetamines might have contributed to this–but clunky dialogue?? He’s hardly a virtuoso stylist, but he always seemed very attuned to the rhythms of human speech to me. Check out his faux-salesman patter in Ubik, to reach for a ready example.

Also, teh Googlz doesn’t lie. Who knows how Harry Potter will be remembered fifty years from now, but from where I’m sitting, there’s no question which is currently the bigger cultural phenomenon.

I think PKD”s prose is often really beautiful. Some of the internal monologues in Man in the High Castle or Palmer Eldritch; the weird last scene in Scanner Darkly…his writing sometimes crumbles at the edges, the way his worlds do, but I find even that effect lovely.

It seems worth pointing out to those that think it too “cartoony” that Barefoot Gen was originally aimed at a pre-teen audience.

Yeah, it’s hard to read it without figuring that out.

Barefoot Gen wasn’t bad, but I kept expecting him to put on a helmet and climb into a nearby waiting Mach 5.

I guess what I’m saying is that considering the grimness of the subject matter, the cartooning style was all wrong. The odd juxtaposition was distracting and jarring to me — as would it be if, say, John Stanley drew a comic book story about the plight of the Donner Party.

Noah:

Re. that other discussion at the comixschl-list: it seems that Supes beats Peanuts: http://tinyurl.com/3zw99cg

Ack! Hoisted by my own algorithm!

Or maybe not quite. Superman and spiderman are very well known as pop culture phenomena, but nobody reads their comics. I suspect the number of people who actually read Peanuts is quite a bit bigger than the number who read capes and tights comics.

Snoopy beats Wonder Woman, at least for the most part: http://www.google.com/trends?q=snoopy%2C+wonder+woman&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=1

Popularity these days is like a flash flood surging through an arroyo. A month later you have a dry gulch.

It’s official:

http://www.google.com.au/trends?q=harry+potter+sucks%2C+twilight+sucks%2C+spiderman+sucks&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=0

————————-

R. Maheras says:

August 23, 2011 at 4:24 pm

Barefoot Gen wasn’t bad, but I kept expecting him to put on a helmet and climb into a nearby waiting Mach 5.

————————–

Heh!

————————–

I guess what I’m saying is that considering the grimness of the subject matter, the cartooning style was all wrong. The odd juxtaposition was distracting and jarring to me — as would it be if, say, John Stanley drew a comic book story about the plight of the Donner Party.

—————————-

John Stanley…Donner Party? “This is a job for…R. Sikoryak!” ( http://www.rsikoryak.com/ )

Not to be a troll, but I really believe Kirby’s and Marvel’s cultural contribution is the superhero aesthetic, and not any particular character. Whether people remember Spidey or Harry 50 years from now seems secondary to whether they’ll need to recognize the influence of superhero comics on late 20th century visual & narrative conventions. If there’s a comparison to be made, I’d say it’s with video games, and how their aesthetic is creeping into other media.

Superheroes are obviously a big deal…but I don’t think you can say bring them down to just Lee and Kirby. Obviously, Superman and Batman are still really recognizable and important…as are the Claremont/Byrne X-Men…as is Watchmen, and, for that matter, something like Ben Ten or Transformers or Buffy which pick up parts of the superhero tropes. It’s just hard at that point to really feel like it’s really about Lee or Kirby in any straightforward way, at least as originators. (Which, again, says nothing in particular about their aesthetic achievement

I think Nate’s right — perhaps in a way he may not even realize.

In the 1960s, Marvel, primarily through its superhero books, almost single-handedly caused a widespread seismic shift in readership age demographics that had been in place since the mid-1930s.

Comics always had a percentage of readership that consisted of older teens and adults, but it was generally a small percentage until the Marvel Universe came along and changed all of the rules. I think the success of Marvel had everything to do with the widespread emergence of a much larger and older teen fan base that later begat and supported undergrounds, led to more adult-oriented fanzines, and forced competitors to address more adult-oriented themes like drug abuse, racial inequality, and other social issues.

Nothing happens in a vacuum, so I don’t think it’s at all a stretch to say that Marvel Silver Age superheroes were the primary catalyst for everything that followed, be it Maus, Fantagraphics or whatever.

Fantagraphics makes sense. Spiegelman is way more oriented towards old newspaper strips than towards superheroes though. I think it’s really a stretch to make Lee/Kirby responsible for him.

Noah wrote: “Fantagraphics makes sense. Spiegelman is way more oriented towards old newspaper strips than towards superheroes though. I think it’s really a stretch to make Lee/Kirby responsible for him.”

Like I said, nothing happens in a vacuum. Spiegelman was heavily involved with reading the comics and fanzines of that era — almost all of which were being heavily influenced by the transformative Silver Age Marvel Universe.

Below is a Spiegelman quote that nicely frames his early “Maus” motivators. The quote is from Arie Kaplan’s 2008 book, “Krakow to Krypton: Jews and Comic Books.”

“What I wanted to make was something I’d thought about as a result of reading ’60s fanzines, like Graphic Story Magazine. And in there there was a discussion of (early 20th century Belgian woodcut master Frans) Masereel, and people like that. And the idea that there could be such a thing as the Great American Novel, but in comics form, was a notion that I vaguely remember seeing there, and it corresponded with something I wanted!”

And if you read the Gary Groth interview of Spiegelman from TCK #180 and 181, it’s very clear that he read and absorbed superhero comics like “Amazing Spider-Man” and the “Fantastic Four” just like he did the works of Kurtzman, Crane and others.

“TCK” above was obviously supposed to be “TCJ”

google trends is fun.

http://trends.google.com/trends?q=batman%2C+harry+potter%2C+pokemon%2C+naruto%2C+disney&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=0

Disney > Naruto > Pokemon > Harry Potter > Batman (which is about even with Twilight). All of the above > Spider Man and Fantastic Four.

Another random point about the inflence of superhero comics indirectly and directly on comics fans. A while back, I indexed, and later scanned the covers of, the first 400 issues of “The Buyer’s Guide for Comics Fandom.” TBG #1-400 were published over about 10 years of comics fandom, beginning in 1971. This was a critical period of comics fandom’s growth which started quite modestly in 1961.

While compiling the index, there was a wide snapshot of artists and writers who were in there early years of creativity. But what I found striking in a number of cases was seeing early superhero-related efforts of creators who later went on to successfully do material that had nothing to do with superheroes. For example, the Hernandez Brothers drew a Doom Patrol cover for TBG several years before they introduced “Love and Rockets.” Likewise, Guy Gilchrist, who currently draws the newspaper strip “Nancy” drew an early cover for TBG featuring a bunch of comics heroes playing poker. And one of one of Dan Clowes’ firts published drawings was a cover for TBG (although it was a space-themed drawing rather than a superhero cover). If I had a copy of my index handy, I could no doubt cite some more examples.

At some point though, there’s a question of whether that stuff was a help or a hindrance, don’t you think? All there was was superhero stuff, so yeah, lots of comic artists saw it. But did it help them? I feel like Spiegelman really doesn’t name check marvel, and doesn’t even like Kirby’s work all that much, right? Does it have to be an influence just because it was around? Did it really help them do the art they wanted to do? Or was it a distraction or an irritation?

And Ave: hip hop vs. comics:

http://trends.google.com/trends?q=hip+hop%2C+comics&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=0

Noah — In his TCJ interview, Spiegelman expressed his ambivalence, and even outright distaste, for Kirby’s work. Yet, at the same time — in a Jerry Springer Show sort of way — he couldn’t stop talking about it.

I think what Marvel’s superhero movement did was draw, through conventions, fanzines, etc., a wide variety of comics-minded people together into a loose, but often unrelated confederation — sort of like a glowing neon sign at night attracting a wide variety of insect species. In the case of comics folks, a convention like San Diego, or a blog like Hooded Utilitarian, is the neon sign.

And I think that, regardless of whatever comics genre floats your boat, if not for Silver Age Marvel (and to a lesser extent, Silver Age DC) superheroes fandom, the huge and diverse comics comics community we enjoy today would probably not exist.

To be fair, it was certain key DC fans like Dr. Jerry Bails who got the ball rolling circa 1961, but it was the rise of Silver Age Marvel superheroes that caused an older, more comics savvy, and more hardcore fandom to explode.

Russ–

I’ve read that interview. The person who wouldn’t stop talking about Kirby was Gary Groth. Spiegelman was trying to humor Gary, but it was obvious he was becoming increasingly impatient with the entire line of questioning. He doesn’t give a damn about Kirby’s work.

Someone should ask Art what he thinks of The Watchmen.

Alan Moore had at least one piece in RAW, so Spiegelman has had some appreciation for Moore in the past, at least….

RSM — I think Gary was trying to get Spiegelman to explain exactly what it was about Kirby’s work he didn’t like, and Spiegelman just couldn’t do it.

But my point was not whether or not Spiegelman liked Kirby’s work, it was that Spiegelman read superhero comics and was a part of the whole diverse fandom movement that developed during that era.

Most fans I knew at the time read a wide variety of stuff, and while everyone had their own preferences, most also had read, or were still reading, traditional Marvel or DC superhero stuff — just like they were reading EC reprints, Mad reprints, Elric, Gods of Mount Olympus, The Spirit, underground comix, Conan, Barks, The Shadow, newspaper strip reprints, or whatever comic book or fanzine happened to be creating a buzz at the time.

“And Ave: hip hop vs. comics”

Ooh, those two are actually closer than I thought they’d be, but the comics one could be skewed by the ambiguity between comics (Jack Kirby) and comics (Chris Rock). Here’s hip hop vs. manga:

http://www.google.com/trends?q=hip+hop%2C+manga

and hip hop vs. movies:

http://www.google.com/trends?q=hip+hop%2C+movies&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=0

one observation (sorry if someone already pointed this out): with Spider Man (and arguably Peanuts, sorry Noah but Newspaper Comics aren’t a very vital art form anymore either) the brand name has probably vastly outpaced and over-saturated the actual story at this point. I think that Noah’s right that people actually read Harry Potter but while (relatively) a few dedicated souls still read Spider Man and everyone knows what he looks like, the story and character are kind of nebulous and not that interesting. Which of course says nothing about how aesthetically influential Ditko might be, just how popular. Potter’s probably more popular than Dickens or Austen too but I don’t think Rowlings is more influential. And who knows, maybe Marvel/Disney’s current approach of copying the comics and rebooting every five years with endless sequels will pan out in the long run, in which case Potter Inc. might have to do the same to compete. For what it’s worth I love Kirby’s art, think Ditko’s Spider Man is okay, and really enjoyed a couple of the Potter movies.

One last google trend – Spider Man vs. Ditko:

http://www.google.com/trends?q=spider+man%2C+ditko&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=0

One of the things about vintage issues of publications like “The Buyer’s Guide for Comic Fandom,” “The Comics Journal,” “The Comic Reader,” etc., is because you can see what trends and topics were hot over a period of time.

TBG was especially good at providing this snapshot because of its frequency of publication and sheer size (it went from a monthly to a bi-weekly to a weekly in a relatively short period in time; and by the mid 1970s it sported multiple sections and averaged 100 or more pages every issue.

Batman and Twilight kick Shakespeare’s butt:

http://www.google.com/trends?q=shakespeare%2C+twilight%2C+batman&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=0

Here’s a link showing the Guy Gilchrist cover of TBG #92, published Aug. 22, 1975 (mis-dated on the cover as Aug. 15, 1975):

http://cbgxtra.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/cbg92.jpg

The Clowes cover (TBG #254) and the Gilbert and Mario Hernandez cover (TBG #274) don’t have cover image links yet on the CBG web site even though I sent the guys at CBG the 400+ scans last year. They’ve only posted links to TBG covers up through TBG #110.

Don Rosa is another former TBG artist and columnist that fans under the age of 30-35 do not equate with superheroes, yet if you read his “Information Please” columns in early issues of TBG, it becomes pretty obvious he was a veritable superhero encyclopedia.

There were a other early TBG cover artists like Phillip Yeh, John Adkins Richardson, Marc Hempel, and a few others, who worked superheroes into their early fan art, but are not known today as artists of that genre.

Back then, there was lots of genre crossover among fans, and no one ridiculed you if you happened to read superheroes, or Barks stuff, or whatever. It was no big deal. I kind of miss that.

———————-

R. Maheras says:

…I would lump Shakespeare and Durer together as popular culture creators of their day, but I’m sure Shakespeare’s audiences were much more economically diverse. After all, a performance at the Globe Theatre cost a penny a person (about $1.50 today), while Durer’s prints no doubt targeted the upper middle class and the wealthy.

Still, we ARE talking about mass audiences in both cases…

————————-

There needs to be a differentiation between works which are fine art and can be both appreciated by the intelligentsia and the “common man”…

…and work which is kitschy crap, aimed solely at the “lowest common denominator.”

In the former case, with Shakespeare’s plays, the better-educated audience members could be moved by the poetry, enjoy the classical allusions; the “booboisie” would more appreciate the swordfights, twists in the plot (when Macduff tells Macbeth — who’s been told that no man born of woman can harm him — that he was not born of woman; he was delivered via Caesarean section!), gawdawful puns (like the shoemaker in “Julius Caesar” saying “all I know is awl”)…

And cheap prints of Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Durer’s “Praying Hands” can be found for sale at flea markets.

In the latter case, there’s utterly brainless crapola like the “Transformers” movies, Kinkade prints, and too much more to mention. Stuff that those with sophisticated tastes can, at best, only appreciate in a condescending “so bad it’s good” fashion.

On some other HU thread I’d posted links to what happens when a worthy work gets “tackyfied” to more appeal to the insensitive tastes of the masses, with hideous versions (night-lights, fountains with colored water; a Bible worked in) of “Praying Hands.” And recently read of how some old-time productions of Shakespeare would be made more “audience-pleasing” by moves like adding a happy ending to “Romeo and Juliet”…

Mike — It always makes me nervous when some “higher authority” in the art world steps in and arbitrarily makes decisions about what is, or is not, art.

In science, rigid standardized, quantifiable characteristics are striven for to categorize things. A result must be measurable and reproducible to be valid. Vagaries are frowned upon.

In the art world, however, it does not appear to me to work that way. It almost seems like anarchy, with clusters of clans fiercely defending their museum turf. Standards of what is and is not art seems to change by generation, probably because there are many in the art world who seem to take pride in tearing down established standards or changing them to suit the characteristics of some new art movement.

I really don’t mind anarchy and the arbitrary rules in the art world per se, because from a creativity point of view, I think that’s probably healthy.

But the art world cannot have its cake and eat it too.

What do I mean? Simple: If there are no set rules and no measurable standards in the art world, then there cannot be any experts. That’s right… everyone’s opinion of what is or is not art is equally valid.

As far as a work of art getting corrupted goes, it’s going to happen. I guess that’s why, in most cases, nothing beats the original. I say “in most cases” because there are instances wher a re-do or remake is better than the original.

For example, film-wise, the the 1941 version of “The Maltese Falcon” was actually better than the 1931 version — even though many of the scenes and the dialogue were identical.

Art-wise, Michelangelo’s “David” statue is a much better, though thinly veiled “re-do” of the Greek statue Doryphoros of Polyclitus.

Russ: “Art-wise, Michelangelo’s “David” statue is a much better, though thinly veiled “re-do” of the Greek statue Doryphoros of Polyclitus.”

How do you know that? You never saw the latter.

———————-

R. Maheras says:

Mike — It always makes me nervous when some “higher authority” in the art world steps in and arbitrarily makes decisions about what is, or is not, art…

———————–

I’d be glad to wear the ermine mantle of ““higher authority” (even more so if a throne came with it, too!); though I never — much less “arbitrarily” — made any “decisions about what is, or is not, art.”

The crucial factor is whether something is “works which are fine art…and work which is kitschy crap…” (Emphasis added.)

If Marcel Duchamp can convert a urinal into a work of art by “recontextualizing” it, when fine industrial design is exhibited in art museums, even the more conservative concede the border between art/non-art is permeable.

Personally, I have no trouble accepting “Transformers II,” the works of “the painter of light,” a tampon in a teacup, a clock incorporating a photo of Elvis polyurethaned onto a piece of driftwood, a “performance art” work that consists of a light switch being flipped on and off, as at least a kind of art. Minimally filling the basic requirement: that a work be intended to create an aesthetic effect.

It’s the quality of the work, as shown by the presence or absence of factors such as…

– Originality

– Creative mastery

– Psychological/intellectual depth and complexity

– Imagination

– The effectiveness with which its creator’s intentions are communicated

…And so forth

…that makes the significant difference. And, even knowledgeable and perceptive critics can disagree on the importance accorded each of those factors. Say, one might favor originality, even when it’s lacking in polish; another give greater weight to Academic-style mastery of execution.

However, that the rules of what constitutes “originality” or “psychological perceptiveness” are not cast in stone, or clearly demarcated as the boiling-point of water at sea level, does not mean we need go to the “anything goes” opposite extreme; maintain that the judgment of the mouth-breathing doofus who proclaims “The Fast and the Furious II” “the most awesome movie of all time” is every bit as valid as John Simon’s arguing that Ingmar Bergman is the world’s greatest filmmaker.

——————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

Russ: “Art-wise, Michelangelo’s “David” statue is a much better, though thinly veiled “re-do” of the Greek statue Doryphoros of Polyclitus.”

How do you know that? You never saw the latter.

——————–

Um, did you mean because it should’ve been called “Doryphoros of Polykleitos?

Actually, Polyclitus is an accepted version of the name:

http://www.oneonta.edu/faculty/farberas/arth/ARTH209/Doyphoros.html

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/miscellanea/museums/doryphoros.html

Mike — Domingos is just being a wise guy. He hates it when low-brows like me make a reasonable point that undercuts his fine art canon.

Um…no reason to get testy. It’s not clear to me exactly what Domingos meant…but he was probably referring to the fact that the original of the Doryphorus appears to be lost (at least according to Wikipedia.) So nobody living has seen it.

Mike wrote: “However, that the rules of what constitutes “originality” or “psychological perceptiveness” are not cast in stone, or clearly demarcated as the boiling-point of water at sea level, does not mean we need go to the “anything goes” opposite extreme; maintain that the judgment of the mouth-breathing doofus who proclaims “The Fast and the Furious II” “the most awesome movie of all time” is every bit as valid as John Simon’s arguing that Ingmar Bergman is the world’s greatest filmmaker.”

But therein lies the rub — when standards are so subjective, who’s to say where the line of demarcation is?

Some of those who pooh-pooh the idea that, say, a Frazetta painting could and should rightfully hang in the Louvre use rationale, that, when closely examined objectively, is arbitrary, illogical, and thus, unfair.

Criticisms like, “Well, Frazetta was not an artist, he was just a commercial illustrator.”

Really? And how were his commissions any different than Rembrandt’s, or Durer’s, or any past artist’s? The fact is, they weren’t any different. If Rembrandt needed money, he’d paint the neighbor’s wife, or a local church official, or some wealthy businessman — just like Frazetta did.

And when arbitrary discriminators like these are peeled away one-by-one, there is little left except personal preference, and that scares the shit out of art experts. And frankly, I don’t care. If the emperor isn’t wearing any clothes, I’m going be that guy who says, “Hey, wait just a frickin’ minute here…”

So any art should hang in the Louvre?

Russ, are you saying Frazetta is objectively just as good as Rembrandt (that it’s not all subjective opinion), or that he’s no better than Matt Feazell (who should have just as good a chance at hanging in the Louvre)?

I think there’s some ground between scientific objectivity and complete subjectivism. There are more or less agreed upon standards which you can talk about and argue for in terms of whether a work of art is good or bad. They’re not absolute, but they make sense (parties to the discussion understand them).

I don’t really care over much what hangs in a museum. I like Frazetta to some extent because he has technical skill and energy. I don’t find his approach especially original, he isn’t very thoughtful, and he happily accedes in some of the less pleasant ideology of his pulp sources. As a result, it’s hard for me to rank embrace him wholeheartedly…though, you know, there are people I like less hanging in museums.

Noah:

That’s right. What we have are Roman copies. A week ago or so I visited the National Archaeological Museum in Athens and let me tell you: the few Greek bronze statues in there (especially with the eyes intact, which is even rarer) are absolutely stunning.

King Lear was often given a happy ending in the 19th century too, believe it or not.

Charles wrote: “So any art should hang in the Louvre?”

Of course not. And no, I do not think Frazetta’s work is the equivalent of Rembrandt’s. But, like Noah said, there are artists with works hanging in museums who, from both a technical and emotional inspiration point of view, Frazetta could paint rings around. So, at the very least, I think he, and other exceptional artists whose work has been effectively banned from art museum consideration because they are “mere commercial illustrators” should get a fair, more objective evaluation by the art world.

Domingos, Speaking of Greek art. Have you seen the Skythian gold? Fucking amazing. I’d never seen the like and wandered around in an art-daze for days afterward. Just beautiful.

Vom: unfortunately no, I’ve never seen it. I must go to S. Petersburg, then…

Time to dig out my crude but succinct artistic nose-tweak of post-modern art:

http://home.comcast.net/~russ.maheras/post-modern-lores3.jpg

The best place to see authentic Greek Sculpture is probably London since Englishmen looted much of the best of it.

If you page through “Greek Sculpture” Lullies and Hirmer, you will see page after page, London, London, with frequent stops in Berlin, and Munich.

Here is a piece of the type Domingos mentioned which is in Athens.

http://www.maicar.com/GML/000Iconography/Anonymous/slides/5213.jpg

Another which was raised from the Sea of Athens.

http://lh5.ggpht.com/-_FRuJZU-BbI/Sns-uQ4cOEI/AAAAAAAAIek/CmrU-SrO48g/25.jpg

Yes, that Paris is great in person (I bet that it is Paris without the apple). The other one looks too Roman though…

The new Acropolis Museum is a political manifesto: it has all the surviving sculptures of the Parthenon (those that survived the puritan fury of the Byzantines and the Venetians bombing) in repro (the lord Elgin ones) and the originals that didn’t leave Greece.

The museum is worth a visit for the Archaic sculpture alone. I suppose that the British and other 19th century colonialists just wanted classical and Helenistic sculpture.

Domiongos: “I suppose that the British and other 19th century colonialists just wanted classical and Helenistic sculpture.”

Very true, I’m more interested in the Crete and Aegean sculpture than later more representational work, but perhaps the British thought the archaic work was cartoonish looking.

They did loot a tremendous amount of archaic vase painting, perhaps because it was easy to transport, or maybe pottery was viewed as a decorative art, and not viewed with the same prejudice as sculpture?

Sculpture would not generally be seen as having as great a narrative quality as painting, but the Greek temple frieze and pediment sculpture at the Temple of Artemis, Temple of Athena, the Siphnian Treasury, Pergamon, etc. were narratives.

Noah, as far as Love & Rockets goes, just start at the beginning. For Jaime, Maggie the Mechanic and The Girl from HOPPERS. For Gilbert, Heartbreak Soup and Amor y Cohetes.

They peaked no later than five-six years into their run, which is pretty much the years these books cover. I don’t think you’ll get much out of reading any more early Gilbert, but surely if you can appreciate Kirby’s artwork then you might appreciate some of Jaime’s.

But yeah, “High Soft Lisp” is terrible. Just wince-inducing. In an interview from some months back, Gilbert said he was burn out with those Palomar-related characters at the end of the first volume of L&R. Well, that series ended fifteen years ago. If he was burn out then, then what is he now? And believe it or not, his story using those characters in last year’s L&R v3 was even worse. As was “Love from the Shadows.” But I did like that surreal short story in the v2 annual from a few years back. Self-contained with no back story or human characters to bring to flesh & blood life.

NB- “You’re arguing it’s not intended to be a stroke book?”

If only it were! I think you’ve got it wrong there. His drawings tend to have a certain grotesqueness to them, partly by design. He’s aged them as times goes on. The “Petra” character who had this perfect athlete’s body is now practically an obese blimp. Who knows what treatment he’ll give “Fritz” in the years to come. Personally, everything he’s doing with those returning characters is so off, so tone deaf, I think he’s just hacking things out.

Getting past Kirby’s groan-inducing dialogue is probably too much to ask for a lot of people. Though I do like parts of his “New Gods,” especially the “Glory Boat” story which I think reaches a certain level of majesty. As bad as his writing can get though, I’d sooner read it than any latter-day Gilbert Hernandez.

Hey Steven. I’ve read Heartbreak Soup, actually (I thought it was eh.)

I think Gilbert gets off on a lot of body types, and on the profusion of body types, and on the alteration of body types. I think High Soft Lisp is definitely about its fetish elements in large part. It doesn’t feel hackish to me; more spiraling into his own not especially interesting obsessions (a la Crumb.)

I like Jaime’s artwork okay.

———————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

….Domingos meant…was probably referring to the fact that the original of the Doryphorus appears to be lost (at least according to Wikipedia.) So nobody living has seen it.

————————-

————————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

…That’s right. What we have are Roman copies…

————————–

If they were copied with the original right there, I have no trouble — considering the exceptionally high standards of skill and artistry the Romans had available — accepting it as a perfectly valid work by which the quality of the original may be judged.

For instance, a copy of the Laocoön: http://www.travelblog.org/Photos/3854387

The original: http://www.mlahanas.de/Greeks/Mythology/Images/LaocoonPioClementino1.jpg

But really, how many of us have actually seen the original of a great work of art? What we usually mean when we say we’ve seen, say, the paintings of Van Gogh, is that we’ve looked at 4-color printed or low-res online copies of photos of those works. Where color balance may be “off,” details and brushwork subtleties lost.

http://www.canyons.edu/departments/ART/images/MAGRITTE%20THIS%20IS%20NOT%20A%20PIPE%201928-29.jpg comes to mind…

(Doing a Google Images search for “magritte this is not a pipe” shows an array of versions of photos of the painting: color tonalities all over the place, cropping varying or borders added, some brightly contrasty, others murky. One may as well call the resulting screenful of images “Ceci n’est pas ‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe’ “…)

…where sculpture is concerned, we may at best see a few views of a 3-dimensional object intended to be observed in the round.

And, there is the “de-contextualization” when works are removed from their intended setting — a temple, cathedral — and set in the neutral, utterly secular confines of an art museum.

Can even visitors to the Parthenon say they’ve truly seen the Parthenon? Aside from its ruined state, no longer being at the heart of the ancient, thriving city it was meant to be in, the bright colors it was painted with (as standard with classical Greek statuary as well) are long gone..

————————

R. Maheras says:

Mike wrote: “However, that the rules of what constitutes “originality” or “psychological perceptiveness” are not cast in stone, or clearly demarcated as the boiling-point of water at sea level, does not mean we need go to the “anything goes” opposite extreme; maintain that the judgment of the mouth-breathing doofus who proclaims “The Fast and the Furious II” “the most awesome movie of all time” is every bit as valid as John Simon’s arguing that Ingmar Bergman is the world’s greatest filmmaker.”

But therein lies the rub — when standards are so subjective, who’s to say where the line of demarcation is?

—————————

Nothing as clear as a “line” exists; but the weight of critical consensus should be significant in assigning merit, and compensates for the isolated wackos who’d consider Mickey Spillane a great literary creator…

—————————

Criticisms like, “Well, Frazetta was not an artist, he was just a commercial illustrator.”

Really? And how were his commissions any different than Rembrandt’s, or Durer’s, or any past artist’s? The fact is, they weren’t any different. If Rembrandt needed money, he’d paint the neighbor’s wife, or a local church official, or some wealthy businessman — just like Frazetta did…

—————————

But, the results of those Old Masters were of a vastly higher aesthetic caliber.

Moreover, Frazetta’s work was aimed at a far larger audience to begin with, and designed to accompany genre writing that, whatever its merits, was not exactly intended for sophisticated tastes.

The nameless chaps cranking out sterile clip-art illos of grinning “suits” shaking hands across a conference table could as well say, “I’m creating art for money…just like Michelangelo, when he was painting the Sistine Chapel Ceiling!”

Yet the painter’s Papal sponsor was infinitely more sophisticated, his expectations far higher, than those of the equally nameless art director for the clip art service…

That Neoclassical copy of the _Laocoön_ is terrible.

Even that early Laocoön is something of a mystery. It was unearthed in the 1500’s outside Rome, and is thought to have been a later (something like 50 AD) copy commissioned by a wealthy Roman of an earlier Greek bronze.

On the relative merits of Rembrandt and Frazetta, I think Fredric Jameson gives a good account of why such comparisons are ahistorical and unhelpf in his well-known essay “Reification and Utopia in Mass Culture” (1979). The essay can be found in his book Signatures of the Visible. A relevant section below:

“Indeed, this view of the

emergence of mass culture obliges us historically to respecify the nature of the “high

culture” to which it has conventionally been opposed: the older culture critics indeed

tended loosely to raise comparative issues about the “popular culture” of the past. Thus, if

you see Greek tragedy, Shakespeare, Don Quijote, still widely read romantic lyric of the

type of Hugo, or best-selling realistic novels like those of Balzac or Dickens, as uniting a wide

“popular” audience with high aesthetic quality, then you are fatally locked into such false

problems as the relative value-weighed against Shakespeare or even Dickens-of such

popular contemporary auteurs of high quality as Chaplin, John Ford, Hitchcock, or even

Robert Frost, Andrew Wyeth, Simenon, or John O’Hara. The utter senselessness of this

interesting subject of conversation becomes clear when it is understood that from a

historical point of view the only form of “high culture” which can be said to constitute the

dialectical opposite of mass culture is that high cultural production contemporaneous with

the latter, which is to say that artistic production generally designated as modernism. The

other term would then be Wallace Stevens, orJoyce, or Schoenberg, orJackson Pollock, but

surely not cultural artifacts such as the novels of Balzac or the plays of Moliere which

essentially precede the historical separation between high and mass culture.

But such specification clearly obliges us to rethink our definitions of mass culture as

well: the commercial products of the latter can surely not without intellectual dishonesty

be assimilated to so-called popular, let alone, folk art of the past, which reflected and were

dependent for their production on quite different social realities, and were in fact the