We’re going to be taking it easy at The Hooded Utilitarian this week. Apart from this post, we’re just going to be publishing the remainder of the lists. We’ll be back with more to engage, enlighten, and outrage next Monday.

My original goal with this post was to discuss the poll results and the comics canon. However, it seems a rather odd undertaking, largely because the notion that the results are indicative of the canon is a conceit. The top ten and Top 115 lists we compiled are indicative of nothing more than the consensus views of the 211 people who submitted lists, and even that is somewhat filtered (i.e., skewed) at points through the perspective of the poll’s editor (myself). Another thing to remember is that those who submitted lists prepared them with different motives. The question they responded to is, “What are the ten comics works you consider your favorites, the best, or the most significant?” A list of “the best” is different than “the most significant,” and both are distinct from “favorites.” Perhaps the best way to proceed is to acknowledge that most of what follows is presumptuous, and if readers want to reject it on that basis, my feeling is they are right to do so. However, I hope they consider the thoughts put forth at least worth considering to a degree.

A few observations about our list:

This project is in some ways a continuation of, and in others a response to, The Comics Journal’s ranked 1999 list of the 100 Best Comics. The Journal list was restricted to English-language material, and relied on opinions from the magazine’s editors and columnists (eight people altogether) rather than on a broader poll. You can see the Journal list here, and a discussion of the thinking behind it here. I’ll talk about some differences between the Journal’s list and ours in the points that follow.

The major newspaper strips are still seen as the most important comics works. We’re supposedly in the graphic-novel era. However, the top three vote getters–Peanuts, Krazy Kat, and Calvin and Hobbes–outpaced the number-four work (and by extension, the rest of the list) by the quite large margin of 14 votes. As far as the poll participants appear concerned, these three strips are the crown jewels of the comics medium. The importance of the great newspaper strips was further reinforced by Little Nemo in Slumberland’s sixth-place ranking, as well as by Pogo coming in eighth. When half the top ten is from a particular mode of comics, I think it’s safe to say the field considers that mode where the most important work has been done.

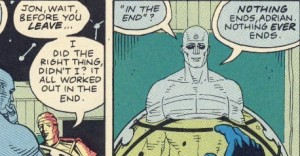

The two most highly regarded graphic novels are Watchmen and Maus. I haven’t come across anyone questioning Maus’s placement yet, but I’m incredulous that some would be surprised—even shocked—at Watchmen’s high ranking in the poll. When it comes to graphic novels, these two works have by far the largest readership constituency outside of the comics community. Maus has sold at least in the high hundred thousands, andWatchmen has sold in the millions. There is no reason for readers to feel they are slumming with Watchmen; the book’s inclusion in Time’s 100 Best Novels and Entertainment Weekly‘s 100 Best Reads lists are reasonable signs that it enjoys the broader culture’s respect. If the larger world holds the book in high regard, it makes sense that this view would be reflected in the comics world as well. Those taken aback by its placement generally strike me as those who have a prejudice against superhero material, or at least the work done in the genre over the last 40 years. I suppose they are like those who turn their noses up at Ian McEwan’s Atonement because of its similarities to category romance fiction, or at Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go because it is a science-fiction novel. Saying a certain work or genre isn’t to one’s taste is one thing; we all do it, and we’re all entitled to that opinion. Treating a work as inherently inferior because it comes from a particular genre is quite another. Watchmen is not just one of the most important graphic novels; it’s one of the most important contemporary novels, period. To act as though the situation is otherwise is at best myopic. I’m not for a moment saying anyone has to like Watchmen, but it should be acknowledged that the book is far bigger than any one person or group’s opinion of it.

The Fourth World will soon eclipse the reputation of Jack Kirby’s Marvel work, at least in comics circles. This is more of a prediction than an observation, but it has its foundation in the poll results. The Fantastic Four’s better showing in the poll was due to all of one-third of a vote. If just one more participant had voted for The Fourth World, it would have been the Kirby work that made the top ten. The Fourth World’s reputation has been increasing over the years, and I doubt it has peaked now. No slight intended against Andrew Farago, but posting The Fantastic Four piece so soon after the Kirby family’s loss in their lawsuit against Marvel was painful. A list in which The Fourth World outranked The Fantastic Four might have been a consolation of sorts. Well, maybe next time.

R. Crumb’s counterculture material is his most important contribution to comics. Noah Berlatsky has wondered if Crumb’s star is falling given the placements of his work in the poll. Noah has pointed to the fact that while Crumb’s Weirdo work made the top ten in The Comics Journal’s Best 100 a dozen years ago, nothing by him made the top ten this time out. I don’t agree with Noah’s speculation. When the Journal’s editors put together the magazine’s Best 100, it apparently didn’t occur to them to create a counterculture-era umbrella entry to cover his works of that period. If they had, I think it would have made their top ten. (And given the material’s ubiquity in the six of the eight contributor lists that were published, it should have.) Judging from those contributor lists and the Journal’s traditional idolatry of Crumb, the Weirdo material’s high placement didn’t reflect the work’s consensus status so much as it did the desire to get something—anything—by Crumb into the top ten. When it comes to Crumb, our poll results likely reflect two things. The first is that the consensus view of Crumb, while one of high esteem, is more measured than the Journal’s. The second is that we did a much better job of giving the counterculture material its due when interpreting the votes. The counterculture work is where Crumb had by far his biggest impact and influence, and I believe this poll’s rankings reflect that it is asserting its proper place in estimations of his career.

Dave Sim is indeed one of the best cartoonists North America has produced. I’m not a fan, and his gender and religious blarney sets my teeth on edge, but there’s no denying his achievements in Cerebus. He is one of the most technically accomplished cartoonists to ever work in the field, and few have managed, much less surpassed, his expansions of the form’s language. Sim did not make the Journal’s Best 100 list. This was despite the fact he and selections from Cerebus were mentioned on at least three and possibly four of the eight voters’ lists. It is hard not to see Sim’s exclusion from the final one as a deliberate snub. I’m glad to see him get a fairly high level of acknowledgement in this poll.

Yes, good English-language adventure comics have been published since 1970. The Journal’s Top 100 list reflected publisher Gary Groth’s view that virtually all adventure comics of the last 40 years (i.e., every one published since he turned 16) are beneath notice. Watchmen, The Fourth World, and V for Vendetta were the only contemporary adventure works acknowledged, and they were kicked to the bottom of the list. (A look at Groth’s personal Top 100 shows he didn’t vote for any of them. Click here.) I’ve already discussed the first two works, and I note that V for Vendetta made our list as well. However, there’s also Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, The Sandman, Bone, Daredevil: Born Again, The Invisibles, and over a dozen others that received listings in our Top 115. Ignoring these efforts while lionizing similar (and to many eyes less accomplished) material from before 1970 was an injustice, and I’m happy we were able to redress it.

The consensus view of The Hooded Utilitarian’s regular contributors both converges and diverges with the consensus of the field. Here are the top 13 vote-getters among this website’s contributing writers:

- 1. Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz [8 votes]

- 2. Krazy Kat, George Herriman [5 votes]

- (tie) Watchmen, Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons [5 votes]

- 4. The Alec Stories, including The Fate of the Artist, Eddie Campbell [4 votes]

- (tie) From Hell, Alan Moore & Eddie Campbell [4 votes]

- 6. The Locas Stories, Jaime Hernandez [3.5 votes]

- 7. Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson [3 votes]

- (tie) A Drunken Dream and Other Stories, Moto Hagio [3 votes]

- (tie) The Fourth World Stories, Jack Kirby, with Mike Royer, et al. [3 votes]

- (tie) Hi no Tori [Phoenix], Osamu Tezuka [3 votes]

- (tie) Die Hure H [W the Whore], Katrin de Vries & Anke Feuchtenberger [3 votes]

- (tie) Journal, Fabrice Neaud [3 votes]

- (tie) The Sandman, Neil Gaiman, et al. [3 votes]

On the basis of this, I’d say we agree with the rest of the field at least half the time.

There’s a lot more to be said about this poll, and a lot more to be said about the comics canon in the future. The canon is a synopsis at a given time of a never-ending dialogue, and lists like the one produced by our poll provide an enjoyable snapshot of where that dialogue stands. They also allow us an opportunity to sit back and take stock. I think Sight and Sound magazine is right to do this just once a decade with movies. The time between polls is neither too great nor too little. It allows people to see the shifts in the consensus view without the overall picture getting too expansive or narrow. And by reserving a special time for judgments, it implicitly puts the emphasis on criticism where it belongs, which is with discussion. Criticism isn’t about being right or wrong; it’s about helping people see work in new and more insightful ways. That can and should go on forever.

Hi RSM!

Again I regret not taking part in this poll and I applaud your effort even though I am just a bit disappointed in the results.

I totally agree with you about WATCHMEN. Intellectuals be hatin’

I am excited about the prospect of THE FOURTH WORLD one day eclipsing Kirby’s Marvel work because its broad scope and unfettered imagination settles once and for all who’s the hottest and who’s garbage.

I am thrilled that my item for the list (it would have been a single-item list) made the general Top 115. My list would have consisted of AKIRA and Akira alone. It specifically changed and shaped my life as a cartoonist and exploror of the comics medium at an age and period in time where no other work could have done.

In the future, I think we will see some love for Moebius’ THE AIRTIGHT GARAGE, a book which comics critic Sean Witzke lays a convincing case for being the greatest and most important single work of all time. I know that Hooded Utilitarian readers have my back due to how much my favorites line up with this 115 list. If you trust me in nothing else, trust me in this: WITZKE WAS RIGHT.

Again, thank you, RSM and I look forward to arguing with you in the future.

-Ayo.

“I’d say we agree with the rest of the field at least half the time.”

Oh great. Our contrarian cred is shot to shit.

Oop I’m a dummy: Airtight Garage DID make the list.

Thanks for this thoughtful summation, Robert. This has been a really intriguing and rewarding exercise, and I can’t wait to see how things change over time.

One nit to pick–having a prejudice against superhero material does not guarantee someone will be prejudiced against other genres, especially as those other genres are much more open than shero work, at least in my estimation. I certainly have a bias against the former–but some of my favorite authors write primarily science fiction. That being said, if an entire medium had been under the exclusive sway of science OPERA ala Flash Gordon for a period of several decades, I think it would be a reasonable stance to want to distance one’s self from the genre, to have a gut reaction to material that used tropes of said genre that was negative in the extreme.

Great job, Robert. I can’t even imagine all the time and effort you put into this. It has been a pleasure to read everyone’s lists and observations (and objections).

Hope you don’t include us in your Watchmen hater rationale. We didn’t object to it on the grounds that it was a superhero comic, rather we engaged in a specific complaint that exposed that many in comics are confused about the definition of rape, or at least are less than concerned about sexual battery. I still believe that if Comedian was prosecuted after being caught in the act he was engaged in, he hopefully would have been incarcerated for a considerable period.

And yes, it is a little embarrassing that HU came up with the same mainstreamed list that Time magazine would have.

Sean–

I didn’t mean to say that a prejudice against one genre meant a prejudice against all. I’m sorry if that’s how it came across. I don’t even have a problem with prejudice towards a genre per se–we all have our tastes. My issue is with the attitude that there’s something wrong with people who don’t share in a prejudice. Or with the myopic view that despite Watchmen’s demonstrable stature with the literary and media establishment, it doesn’t rate inclusion in a serious consensus top-ten comics list.

James–

The objections to the handling of the attempted rape are based in a very direct grappling with the substance of the book. I don’t agree with them, but I’m glad to see them raised.

James–

As I noted, we at HU–disparate voices that we are–agree with the comics field at least half the time. We can agree with Time every now and then, too.

Qiana-

Thanks so much.

I feel it’s part of HU’s mission to piss off even contrarians on occasion.

“Dave Sim is indeed one of the best cartoonists North America has produced”

Don’t shortchange Gerhard! A vote for Cerebus is probably at least 1/3 a vote for Gerhard — or mine was, at any rate.

RSM wrote: “A list in which The Fourth World outranked The Fantastic Four might have been a consolation of sorts. Well, maybe next time.”

I don’t see why. Kirby didn’t have ownership for Fourth World either, did he?

Speaking of Fourth World stuff, for the first time in a decade or so, I sat down an re-read the “Jimmy Olsen” stories written by Kirby from that era. His dialogue was just as stilted and painful to read as I remember.

I was 16 years old when Kirby made the transition from Marvel to DC circa 1970, and because Kirby was hands down my favorite artist, and since I was an artist myself, I was one of those who was rooting his new Fourth World books would be spectacular.

But while the art, characters and basic concepts did not disappoint, the dialogue was horrible. It was jerky, odd, and just plain unnatural. I don’t know how many times over the years I’ve tried to sit down, re-read and “like” the stories, but the results are always the same.

There was a reason those books failed to catch on when they were first published, and time has not changed that one iota.

No ownership, but my understanding is that he (and now his estate) receive royalties from the use of The Fourth World characters.

<<<>>

Russ: I and many others disagree with your judgment completely and like Kirby’s writing much more than Lee’s now-dated blurbwriting. Kirby at his solo best leaves Lee in the dust.

I can point to Marvel’s flooding of the market with Kirby reprints at that time as detrimental to Kirby’s DC books, and to the early fan speculation and the actions of corrupt distributors as the reasons why so many innovative books got canceled at that time.

James wrote: “Russ: I and many others disagree with your judgment completely and like Kirby’s writing much more than Lee’s now-dated blurbwriting. Kirby at his solo best leaves Lee in the dust.

I can point to Marvel’s flooding of the market with Kirby reprints at that time as detrimental to Kirby’s DC books, and to the early fan speculation and the actions of corrupt distributors as the reasons why so many innovative books got canceled at that time.”

Regarding your first comment, my view had nothing to do with a “Lee vs. Kirby” rivalry. I was extremely pro-Kirby prior to the Fourth World’s release, remember? The problem for me was not so much that Kirby’s dialogue was different than Lee’s, it was that Kirby’s dialogue was different than that of ANY writer whose work I enjoyed. And it wasn’t just the dialogue itself, it was the erratic dialogue FLOW that often drove me nuts.

Regarding your second point, it just does not wash. There were a number of comics introduced at the same time as the Fourth World series that survived just fine — Marvel’s run with Conan, for example. Why did some “cream” rise to the top during the glut, yet no Fourth World books — especially since I believe all of the Fourth World books started out with very strong sales initially? The answer is simple: Many fans felt the same way as I did about Fourth World dialogue.

RSM wrote: “No ownership, but my understanding is that he (and now his estate) receive royalties from the use of The Fourth World characters.”

Small consolation, ya think?

Russ–

The books that suffered from the early-speculator/corrupt-distributor problems in the 1970s were invariably costumed-superhero titles–The Fourth World books, Green Lantern/Green Arrow, etc. The comics dealers of the time generally didn’t target books like the Thomas/SmithConan or the Wein/Wrightson Swamp Thing, so they got distributed to newsstands and did quite well there, at least before the speculators caught on.

RSM — please elaborate on your distribution/speculator theory, because I saw the effects of both first-hand. For example, I knew, personally, a number of big-time speculators from that period (I actually worked for one for a few months or so); and I also worked for Charles Levy Circulating Company, then the Chicago area’s ONLY distributor, from 1974-1978.

If you read Carmine Infantino’s TCJ interview, he mentions the high sell-through enjoyed by the Wein/Wrightson Swamp Thing.

With Conan, the comic-book launch had done well enough in newsstand sales to justify publication of a second title featuring the character–Savage Tales–a little more than six months later.

Also, when Barry Windsor-Smith left Conan, John Buscema took it over. Despite lobbying for the assignment before the title began, he had not been allowed to draw it then because the title’s budget couldn’t accommodate his page rates. The budget had obviously been increased enough to pay him after BWS left. I can’t see that happening unless the newsstand sales justified it.

The speculators obviously weren’t undermining the sales of these books the way they had with GL/GA, The Fourth World titles, etc.–all of which were ridiculously easy to locate from comics dealers in the early ’80s, I must say.

Gee, Russ, our disagreement about the relative merits of Kirby’s writing and Lee’s blurbing could be a matter of taste, except that I believe Jack wrote his Marvel work in every way that counts, AND it seems like you have a vested interest in dismissing my other point.

RSM — You really didn’t address how speculators and a corrupt distribution system singled out and hurt sales of Fourth World titles but allowed other titles to thrive.

The way I see it, speculators and distribution was a minefield every title from that era had to contend with.

So I don’t see how anyone could draw any other conclusion then ’twas the market that originally killed the Fourth World — despite the fact that early fan anticipation gave Fourth World a circulation headstart the first couple of issues that many of its newsstand rivals did not enjoy.

Of course I can’t say with certainty exactly why the Fourth World did not catch on in an era when Conan and others did, but since everything about the series was pretty damn excellent except the weird dialogue, that’s seems to me like a logical place to start.

James wrote: “Gee, Russ, our disagreement about the relative merits of Kirby’s writing and Lee’s blurbing could be a matter of taste, except that I believe Jack wrote his Marvel work in every way that counts, AND it seems like you have a vested interest in dismissing my other point.”

I don’t argue that liking Kirby’s dialogue is a matter of taste. I just argue that there were not enough people who liked Kirby’s Fourth World dialogue to support the titles over the long haul.

What “vested interest” would that be? I have no vested interest in the comics biz.

I can’t speak to the specifics of The Fourth World. I don’t think anyone can do anything but guess about it. All anyone knows for sure is that the sales levels reported by magazine distributors to DC were poor. But we also know that a fair number of those reports were fraudulent, in no small part because books that had attracted speculator interest were being sold under the table.

I do note that any comics shop I went into during the early 1980s–I was in middle school at the time, and went back and forth between Michigan and Florida–had substantial inventories of New Gods, Mister Miracle, etc. at low prices in the back-issue and clearance boxes. That suggests to me the titles had been stockpiled for speculation purposes, and that the hoped-for gouging hadn’t panned out. However, I admit this is anecdotal.

Well, how weird that Kirby had his own style….um, is this comics we are talking about? Did Stan Lee write deathless prose? I think not. Bummer, Faulkner reads differently from Hemingway and neither copies Shakespeare. Off with their heads for breaking the “rules.” Do you also prefer your artists to draw the same?…and, perhaps you were working at the lone honest distributor from those days. But you also ignored that Marvel flooded the market with Kirby reprints, any given month in the early seventies there were many more Marvel Kirby books on the stands than his new DC titles.

“Those taken aback by its placement generally strike me as those who have a prejudice against superhero material, or at least the work done in the genre over the last 40 years.” I think your doing a disservice to those who aren’t fond of Watchmen. The problem for me isn’t that it’s a superhero comic — there are plenty of superhero comics that I like and wouldn’ have objected to on the top ten, including Kirby’s 1970s work. The problem with Watchmen are artistic problems: issues of narrative coherence and tone and allegorical affectiveness (it’s not clear to me that superheroes can bear the real world political implications that Moore wants them to have). These are serious issues and despite the popularity of Watchmen continue to make me question its placement so high on the list (although it does belong on the top 100 or 115 or whatever).

As for Crumb, again it’s not clear to me that it makes sense to separate his work out into different periods when you are comparing him to cartoonists who created bodies of work over several decades. Just as 44 years of Krazy Kat and 50 years Peanuts are a body of work, so the whole of Crumb should be seen as a single project.

Superheroes as tropes exist in the real world. Therefore they have real world political implications. Among those are our cultures obsession with vigilanteism, progress, power, violence, and deus ex machina solutions to complicated problems. Moore and Gibbons weren’t creating those real world political implications; they were exploring them — quite thoughtfully, it seems to me.

And…if Crumb’s body of work should be treated as a whole, why shouldn’t Moore’s…which would then make him the winner of the poll by a fair margin? The poll was of works, not of cartoonists, as was the tcj poll. People obviously, and understandably I think, believe that as a single work something like Peanuts or Calvin and Hobbes is more impressive than any single work Crumb has created. And…did anybody vote for Crumb’s body of work as a whole? I don’t think so…because it doesn’t have that kind of coherence or unity of focus. He’s done lots of different kinds of projects, and hasn’t ever really created a giant coherent magnum opus, because he’s not a giant coherent magnum opus kind of cartoonist.

Nonetheless, Robert did try to balance the scales somewhat by creating a category for some of Crumb’s most important work. That seems fair.

RSM — From what I saw, speculators HELPED sales. For example, in late 1972, a speculator I was then working for showed me a skid full of 5,000 copies of “Shazam” #1 he BOUGHT (on a then unusual non-returnable basis) from the distributor in the hopes that he could corner the market and later sell them for $5 a copy — an astronomical price in those days.

He and a couple of his buddies ran one of the first comic book stores in the Chicago area, and while they did manage to sell a small number of copies at that inflated price, market realities soon force them to lower their prices drastically. It seems that they only managed to buy a fraction (albeit a BIG fraction) of the Chicago allotment of “Shazam” #1s, and every savvy fan in Chicago swooped in and bought practically every other copy that was distributed through normal channels.

Thus, within months, you could buy a copy of “Shazam” #1 in NM condition for darn near cover price at the monthly Chicago minicons. And because speculators had done the same elsewhere around the country, it was decades before a “Mint” copy of “Shazam” #1 finally reached the $5 point in the Overstreet price guide.

For example, in the 1985 Overstreet edition, published a dozen years after “Shazam” #1 hit the stands, a “Mint” copy was listed at only 60 cents — and even THAT was wishful thinking at the time.

James — You’re fixating on Lee’s writing, for some reason. When Fourth World was going at full steam, I was a senior in high school, I’d been reading comics for more than 10 years, and I’d been a hardcore fan for nearly four years. I knew most of the writers and artists at the major comic book companies by heart, and I’d even started working backwards in time, discovering (or re-discovering) earlier Silver Age or even Golden Age stuff. So it was not just the fact that Kirby’s dialogue was weird and stilted compared to Lee’s — Kirby’s dialogue was weird and stilted compared to almost every other writer out there!

But while even some of my own fan buddies liked Fourth World back then as well, the fact is, there just weren’t enough of them.

Now, you can keep denying it all you want, and you can cite conspiracy theories, bad breaks, sunspots, or whatever, but with the exception of “Kamandi,” I don’t think any other Kirby dialogued title after Fourth World made it to the two-year mark.

And while I respect Kirby’s desire to not get stiffed any longer regarding who created what, there’s a reason for that: Kirby’s odd dialogue had only niche appeal.

————————-

James says:

Well, how weird that Kirby had his own style….um, is this comics we are talking about? Did Stan Lee write deathless prose? I think not. Bummer, Faulkner reads differently from Hemingway and neither copies Shakespeare. Off with their heads for breaking the “rules.” Do you also prefer your artists to draw the same?…

—————————

It’s not as if Russ was arguing that Kirby shouldn’t be entitled to have his own writing style; more that it was undeniably odd and “funky,” and arguably off-putting to readers, especially when compared to the slick, pseudo-hip patter of Stan Lee.

Though I’m wondering if it was other factors responsible for the commercial failure of the “Fourth World” books: that Kirby’s creativity was just too weird for those stodgy DC readers; that art tastes among fans were changing, their worshipping at the altar of Neal Adams and his imitators instead, with Kirby looking crude and clunky in comparison…

<<<>>

I was younger than you when the 4th World books came out and truthfully, the dialogue didn’t bother me. In fact I preferred it to the stale text of Jack’s late Marvel work—-Stan Lee was unable to generate excitement without Kirby’s plots to guide him (Jack had ceased to invest his creativity into the books near the end because he was sick of Lee ruining his stories). And, I never particularly enjoyed the verbal prolixity of say, Don McGregor, Gerry Conway or Roy Thomas’adaptations.

Another factor in the 4th World books’ cancellation was that DC withdrew their support when the books were not overwhelming runaway hits because of the distribution and Marvel market-flooding issues I have previously noted. The worst of it was that the cancellation of his flagship 4th World titles came just as he was hitting a high point with his actual writing. The books he did directly before the cancellation are his career masterpieces.

Russ–

Robert Beerbohm and others have discussed at length the practices of speculators and distributors in the 1970s. In instances like the one you describe, the distributor then filed bogus sales affidavits that reported the books as unsold and destroyed. Yeah, it helped sales, but not for the publishers, who were being ripped off.

RSM wrote: “Robert Beerbohm and others have discussed at length the practices of speculators and distributors in the 1970s. In instances like the one you describe, the distributor then filed bogus sales affidavits that reported the books as unsold and destroyed. Yeah, it helped sales, but not for the publishers, who were being ripped off.”

You’re ignoring the obvious here: Why were Fourth World books then allegedly singled out by distributors? Corrupt distribution practices would affect all comics across the board.

As I pointed out to James, with the exception of “Kamandi,” I believe that all post Fourth World titles sporting Kirby dialogue withered and died before the two year mark — and this trend continued long after the direct market was established.

And if you think about it, “Kamandi” may have lasted as long as it did for the simple fact that Kirby’s odd dialogue may not have seemed out of place when coming from talking animals and a kid living in a post-apocalyptic world. In addition, Kirby wasn’t scripting the title during the last year or two of the titles run.

James — Though I don’t know the specific details, it was reported that Kirby’s contract with DC was very expensive. If that’s the case, it was probably built around the premise that Kirby’s books would reach a certain sell-through circulation level. When the books did not have the wide appeal DC had hoped for, they had no choice but to pull the plug.

I think the whole “Marvel undercut Fourth World sales by flooding the market with Kirby reprints” is a red herring. I was there during the beginning, middle and end of the whole Fourth World saga, and the Marvel reprints did not affect my purchases of Fourth World books one iota. I stopped buying the books for two reasons: First, and foremost, the dialogue was distracting and weird. Second, I did not like the way everything was intertwined across multiple titles and that the overall storyline was continued ad infinitum.

Put it all together, and I stopped buying.

Russ, for the sake of accuracy, “the last year or two of the title’s run” unscripted by Kirby was actually four monthly issues. The first thirty-six were terrific.

Mike — Not true, Mike. There were 59 total issues of Kamandi, and Kirby had nothing to do with the last 20. And while Kirby drew #38 and 39, Gerry Conway did the scripting.

That said, Kamandi was Kirby’s longest running series from 1970 until he passed away, and it was a fun series.

For the record, here’s a rough idea of how long Kirby worked on various titles after first leaving Marvel in 1970. (Note: I’ve omitted stuff like the Topps Kirbyverse, Destroyer Duck, a number of intentional one-shots, etc.)

Jimmy Olsen (1970-1972) – 16 issues

News Gods (1971-1972) – 11 issues

Forever People (1971-1972) – 11 issues

Mister Miracle (1971-1974) – 18 issues

Demon (1972-1974) – 16 issues

Kamandi (1972-1976) – 37 issues

OMAC (1974-1975) – 8 issues

Sandman (1974-1976) – 6 issues

Our Fighting Forces Losers (1974-1975) – #151-162 (12 issues)

Dingbats of Danger Street (1975) – 1 issue

Captain America (1976-1977) – #193-214 (22 issues)

Eternals (1976-1978) – 19 issues

2001: A Space Odyssey (1976-1977) – 10 issues

The Black Panther (1977-1979) – 12 issues

Machine Man (1978) – 9 issues

Devil Dinosaur (1978) – 9 issues

Captain Victory… (1981-1984) –13 issues

Silver Star (1983-1984) – 6 issues

In my mind, the sheer number of Kirby’s ideas over the course of his career, along his overall artistic prowess, was unparalleled.

I just didn’t like his dialogue.

One additional comment about the list above. In virtually every case, the publishers gave Kirby’s books a reasonable amount of time to flourish. The sales results start coming in after about three months, so it does not appear as if the publishers were ever quick with the trigger.

If we’re going to be anal about it, Kirby only drew four of those six Sandman issues…

James, for the high-point of Kirby’s writing post-1970, I’d vote for “The Eternals” rather than The Fourth World Saga, myself. With maybe OMAC and 2001 tied for second place. “The Eternals” is as close as comics get to William Blake’s epic poems–including all their awkwardnesses, which in both cases make them more fascinating. (And one can also draw comparisons between late Kirby and Blake’s art; Kirby would have made one hell of a visionary artist ca. 1800.)

I don’t want to keep arguing with you Russ, it is pointless because your thing is a taste issue….but after the supreme fucking that the Kirbys just got, it seems pretty cold to keep hammering about the dialogue. It’s as if you are rubbing it in.

Who cares that Stan Lee did slick blurbing, he screwed his collaborators completely and so his legacy is hideously tarnished.

Andrei, I like 2001 and a few of the Eternals issues very much, but I don’t think Kirby ever reached a higher peak than the issues of the 4th World published just before DC cancelled the epic.

James — Since when is a critique of an artists work dependent on a legal decision or contract dispute?

Over the course of his career, Kirby’s most successful comic book work was achieved when he was given free reign to visually create stories and characters from virtually nothing, after which someone else followed behind and did the scripting. The same goes for Ditko.

There’s nothing wrong with that, provided the artists get proper credit for their creativity.

Kirby got shafted, credit-wise, and, like Ditko before him, he opted to “break up the band.”

But, just like the Beatles, when Ditko, Kirby and Lee split up, none of the individuals ever achived the levels of artistic success they enjoyed when they were all working together.

A few of the reasons I opted out of a career in comics in the late 1970s is because, if I worked for any company from that era, I would not have ownership of anything I created, and, for anything created via the “Marvel method,” I would probably get short shrift on credit compared to any projects scripter.

Like Kirby, after a certain point in my life, when I did work on a comic book-style project, I decided to do everything myself — even inking, lettering, and, on rare occasions, even coloring. I did this KNOWING that the results would most often be inferior than if I worked with other creators. However, I also knew that there would never be any confusion about “who created what” — even if the project was a piece of crap of epic proportions.

Jeet–

Sorry for the belated reply. I’ve been pretty tied up the last few days.

I’ll probably further discuss the issues of categorizing Crumb’s work in a post. It’s a good conversation to have, and I’m glad you’re bringing a view opposed to mine up.

With regard to Watchmen, what’s myopic is not disagreeing with its reputation–we’re all entitled to our opinions–it’s disagreeing that the book has the reputation it does. It is the preeminent fiction graphic novel produced in the English language. Considered alongside prose works, it is also among the key works of English-language fiction of the last quarter-century. No other fiction graphic-novel work comes close to Watchmen’s stature. Not Locas, not From Hell, not Jimmy Corrigan. Or Palomar, Sandman, or Black Hole. Maus (and perhaps–eventually?– Fun Home) can claim a similar stature to Watchmen in the world outside comics, but they’re not fiction works.

A lot of the great prose novels are arguably flawed to a degree. It’s generally accepted that Huckleberry Finn goes to hell in a handbasket in its final section, after Tom Sawyer reappears. People argue to this day about the value of the passages dealing with the finer points of whale knowledge and whaling in Moby-Dick. I think Proust could have stood to edit some of the salon-party scenes in In Search of Lost Time down a good deal. Virginia Woolf had some pretty cutting things to say about Jane Eyre. But it doesn’t matter; a great work is great despite its shortcomings. And what are shortcomings to some may prove powerfully resonant to a different set of readers.

That touches on another thing I’ve noticed: You tend to treat the platonic notion of greatness in art as a given. You don’t seem to view it as a conceit. Am I misreading you?

<<>>

Well, there’s the rub, Russ. You were discouraged from trying. That’s sad.

By reversing his own previous documented statements about how much his collaborators contributed to the work in court, Stan Lee made himself clearly the villain. The case was lost on his words. Before, the worst I could say about him is that he didn’t stand up for his artists like Kirby when his uncle sold Marvel and reneged on his promises. Now, Lee’s name is officially mud.

And, if the denial of the full credit of co-authorship to artists in collaborative comics continues, we might see quite a lot of writers lacking artists (“hands”) of quality who will be willing to work for said diminished credit. I’d wager that most artists who want to work in comics will all be trying to write for themselves as hard as they can.

Robert:

“I think Proust could have stood to edit some of the salon-party scenes in In Search of Lost Time down a good deal.”

If you say that you’re not reading Proust in a proper way, it’s not _Warchmen_, you know? Proust can’t be read because of the story. There’s almost no story to tell. Proust is great because he was a hell of an observer. What’s great in is writing is exactly the nuanced, highly detailed description of the characters’ behaviour. Iy’s not a pretty picture to see, I know that, but I believe that humans are exactly like what he says they are…

Domingos–

Proust is one of my three or four favorite authors, and I’m pretty firm in my view that In Search of Lost Time is the finest novel of the last century or so. I ‘ve read nothing that’s been produced since World War II that even begins to compare with it. That said, the salon-party scenes–which, for those not familiar with them, go on for literally dozens of pages–have always been one of the least interesting aspects of the work for me. On a moment-by-moment basis, they’re hard to fault, but after thirty or so pages of one, I can’t help but think it’s time for the book to move on to something else. I’m not questioning the material; I’m questioning the duration. By the same token, I love Miles Davis, but I don’t want to listen to him perform a half-hour solo on his trumpet, either. There comes a point when things lose their freshness, and the attention begins to wander.

That’s funny, I just want more and more of it… I never tire to see how the characters interact according to social position and psychological motivations…

I’m so sure that Proust could have been better if he had an editor like Stan Lee to help him. And likewise, Miles could have benefited from following Solieri’s advice. Choke.

James wrote: “Well, there’s the rub, Russ. You were discouraged from trying. That’s sad.”

Not sad at all. You weep for Kirby’s plight, yet you tell me it’s sad I was “discouraged” for not entering a rigged game.

Not getting into the comics business during that point in history was the smartest decision I ever made.

???????

I guess we’ve hit a logjam, Russ. The plight of Kirby and his contemporaries stopped you from doing corporate comics but still you defend Lee, who made that plight worse by exploiting his artists and taking full writing credit and full writing paychecks that he did not deserve…and bummer, I do not even

value the writing he DID do at all. His recent actions have ended any leeway I was willing to give him.

We are not going to agree on this, so we might as well crap it off.

James — How exactly did I “defend” Lee? By saying the Silver Age work he produced with Kirby and Ditko was successful? In fact, it was.

Or do you consider it a defense of Lee because I criticized Kirby’s Post-1970 dialogue writing, and showed how it was less commercially successful than work he co-produced with Lee? Again, in fact, it was.

I think Kirby knew he wasn’t all that great at writing dialogue, but after a certain point in his career, he just didn’t care any more. He had been burned too often by the inherent unfairness of the “Marvel Method” in giving the artist his/her fair share of credit compared to the scripter.

For “idea artists” like Kirby, the artist could very well be responsible for 95 percent or more of a given story’s creativity, yet, in the credits, the only billing the artist usually got was “pencils by.” Ditko rightfully thought such an inequity was unfair and he apparently pressured Lee, successfully, to give him “plotted by” credit.

Kirby obviously should have gotten similar credits during that same period for Fantastic Four, Thor and other books, but Kirby apparently didn’t push for it. Why? Only Kirby could tell us, but I suspect it was the fact that he didn’t want a repeat of the earlier problems he had at DC just a few years earlier where he basically got blacklisted.

This was in about 1965, but apparently Kirby’s frustration was building more and more with each passing year, so when DC’s new regime opened up to him circa 1970, Kirby finally had a relatively safe outlet for his frustration that would not hinder his earning power and hurt his family.

During the 1970s, I watched all of these, and a number of other dramas of inequity involving artists unfold. These, along with the fact that freelancers then received exactly NONE of the non-salary benefits I was used to at my union job, was enough to make me look elsewhere for a career.

So you want to know what’s really sad about this whole deal? The fact that so many of my creative contemporaries who entered the comics biz, and for decades poured their heart and soul into it, can no longer get regular work and have fallen on hard times.

Weep not for me, James — I have no complaints and no regrets.

Hard to type since I’m weeping so much, ha ha, but I am unconvinced that the dialogue was what tanked Jack’s books. I named some other potential culprits but you dismissed them without making any convincing case against them. You base your judgement on your youthful take on the material but I do not think that you as a high school senior were necessarily the target audience for Jack’s books, which were written for younger kids.

And I make no claim that all of Kirby’s solo work was brilliant.

At his best, he was capable of story and art that leaves his contemporaries in the dust. But Jack was also more than capable of knocking out simple action stories with no real substance or even hacking out rush jobs. For instance, other than the annuals and Bicentennial Battles, I find his solo run on Captain America

extremely challenging textually. So, I’m not deluded here.

But as I said, the sad thing is that in his solo work for both Marvel and DC, just when he had a grip on a solid and productive storyline and was writing text (dialogue and captions)that had resonance and weight, the rug was pulled from under him–witness

the rapid declines in New Gods and Eternals after the editorial disempowerments that interrupted some of his best efforts.

Of all of Kirby’s post-1970 work, I think I liked “In the Days of the Mob” and “The Eternals” the best.