It’s been a while since the last installment, but it hasn’t been uneventful for me, what with a house purchase, a death in the family, a move, and several other sorts of things. But we’re finally back to the quest! Today, cocoons, reunions, and tall dark handsome strangers!

Monthly Archives: September 2011

Is the Bamboo Curtain More Treacherous Than the Glass Ceiling?

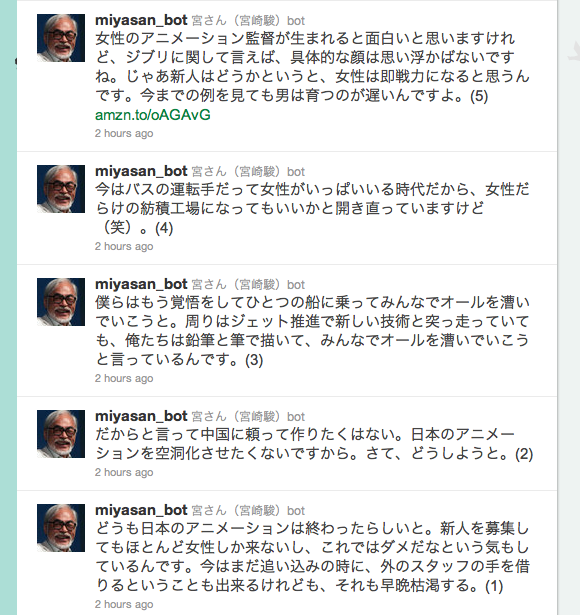

I read an odd entry in my Twitter feed the other morning. Not unusual for a forum dedicated to misinformed celebrity rants and the beekeepers that idolize them, but what struck me about this tweet was that it came from the account of Hayao Miyazaki, He that is Deus in the Machina at Ghibli Studios, and dare I say… a generally uplifting and motivational Twitterer. Bear in mind the Japanese language is composed of ideographs, so 140 characters can read like an American paragraph. Nonetheless, this morning I read this:

@Miyasan_bot:

They say it’s over for animation in Japan. When we look for new hires only women respond, and I get the feeling that we’re done for. In our last hurrah we borrow from outside staff (i.e. outsource), but soon we won’t be able to do that forever.

OK, now mind you, Miyazaki’s been talking a lot about the end of anime on Twitter lately. Sort of the same way people are decrying the end of print publishing. He’s not giving up on animation but suggesting it might be best to face up to the fleeting nature of all things. Yes, his micro-wisdoms border on sermonic.

So what I found interesting in this tweet was the casual observation that a sign of decline was that only women are responding to job solicits. He wasn’t trying to say anything about women. He was saying it’s over for Japanese animation. The bit about women was just a bit, but the mumble was deafening.

So I mustered some courage and replied to him.

@ill_iterate:

Really, @miyasan_bot?

I didn’t get a response per se… A few hours later, I saw this in my feed:

A five-part transcript of the whole statement from which he’d excerpted the top line earlier in the morning. The full statement is from a lengthy interview in Eiga pia (Movie Peer) magazine

@miyasan_bot:

Part 1:

They say it’s over for animation in Japan. When we look for new hires only women respond, and I get the feeling that we’re done for. In our last hurrah we’ll borrow from outside staff, to lend a hand but we can’t do that forever.Part 2:

These are not reasons for me to take production to China. I don’t want to deplete Japan in that way. So, what do we do?Part 3:

(Ghibli Studios) has been resolved to rowing the boat altogether as a team and giving it our all, while everyone around us is jet-propelled with new technology and running at full-speed. We still illustrate with pen and paper. I say we continue to give this our all, together.Part 4:

I counter the point some make that we’re in an age where you’ll find women driving buses by asking if it’s ok to have women all over cotton mills. (LOL)Part 5:

I think it would be great to see a female animation director, but as far as Ghibli’s concerned, I can’t think of a single one for us. So what about newcomers? Well, I believe women are incredibly fast-learners and self-starters. If you look at men, even today, they develop much slower.

I’ll cut to the chase: What do I see in the full statement? More obfuscation of the glass ceiling, but a genuine interest in seeing it shattered.

The first part of his quintweet is sort of unfortunate as there’s not doubt about it. He just said: women in the employment queue bum me out. Chauvnism is colorblind, deaf, and a little obnoxious, but well, let’s see what else he’s saying.

In Part 2 of the quintweet, Miyazaki calls out the harsh realities of competing with China for animators and technology. It’s a problem in just about every industry outside of the People’s Republic. From textile manufacturing to bootlegging Apple retail, we the people of everywhere else is kung-fucked. I empathize as my bootleg Apple store doesn’t stand a chance against theirs.

In Part 3 Miyazaki explains how Ghibli’s work is a labor of love. As much a labor as the biggest animation production company in Japan whose American distributor is Disney (one of the biggest media companies in the world) can be. Though it is really beautiful that they work in analog. I mean that. No one watches Pixar to see peach-shaped marhsmallow humanoids. No, we fell with the kid from Up because he was part of a good story.

Part 4 is as baffling as it is evocative to me. Miyazaki’s recapitulating his point about evening the status by playing devil’s advocate to some truism that “women are even driving buses now.” I’ve never thought of it that way, but (thinking…) yeah I guess it’s sort of a man’s world behind that huge steering wheel in Japan. In New York City I think every third bus driver I’ve encountered has been female but it just goes to show… Strange where we engender jobs, isn’t it?

Moreover, to counter the observation on female bus drivers by suggesting labor-equality can turn be flipped and end us up with sweatshops full of women begs the question… has Miyazaki picked up a newspaper in the last decade? These cotton mills ARE populated by women. This statement is what baffled me most particularly. Cotton mills? I’m hoping it’s

lost in translation. Hoping cotton mills is Japanese for Dick Shop. And yet…

there is no mistaking “LOL” which I’m positive is the correct translation of (laughter):![]()

My conclusion from Part 4 of the Quintweet is that for Miyazaki, status quo is an issue that starts with the basic tenet that women do work at all. Amazing to think the studio responsible for so many phenomenal heroins doesn’t think women actually earn their keep in modern professions. Actually I take that back. Nausicaa is an animist warrior; Chihiro and Ponyo are both children, as are Totoro’s neighbors. The closest thing to a working professional woman in Ghibli films is a witch who delivers packages from a bakery. [Note: I LOVE all these films and still think primary, secondary and all tertiary female characters could categorically kick every female animated Disney character in the proverbial “Pocahontas”.]

And finally, Part 5. “Show me the women!” he says. Damn straight. And this is the variable that changes my perspective on the entire argument against his seeming indifference to the glass ceiling. Women are fast learners. Men are comparatively late-bloomers. Get a leg up, women! Get out of the cotton mills, stop driving all those buses and start rowing this boat to nowhere.

Big Questions: Our Father, Where Art Thou?

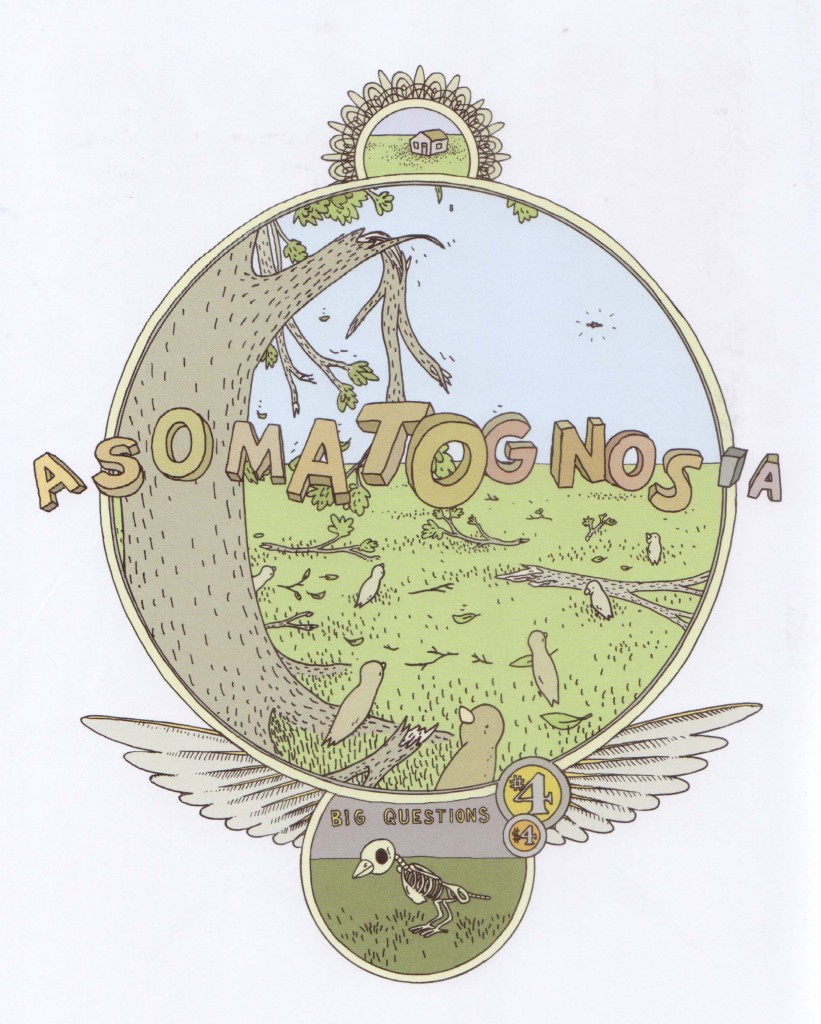

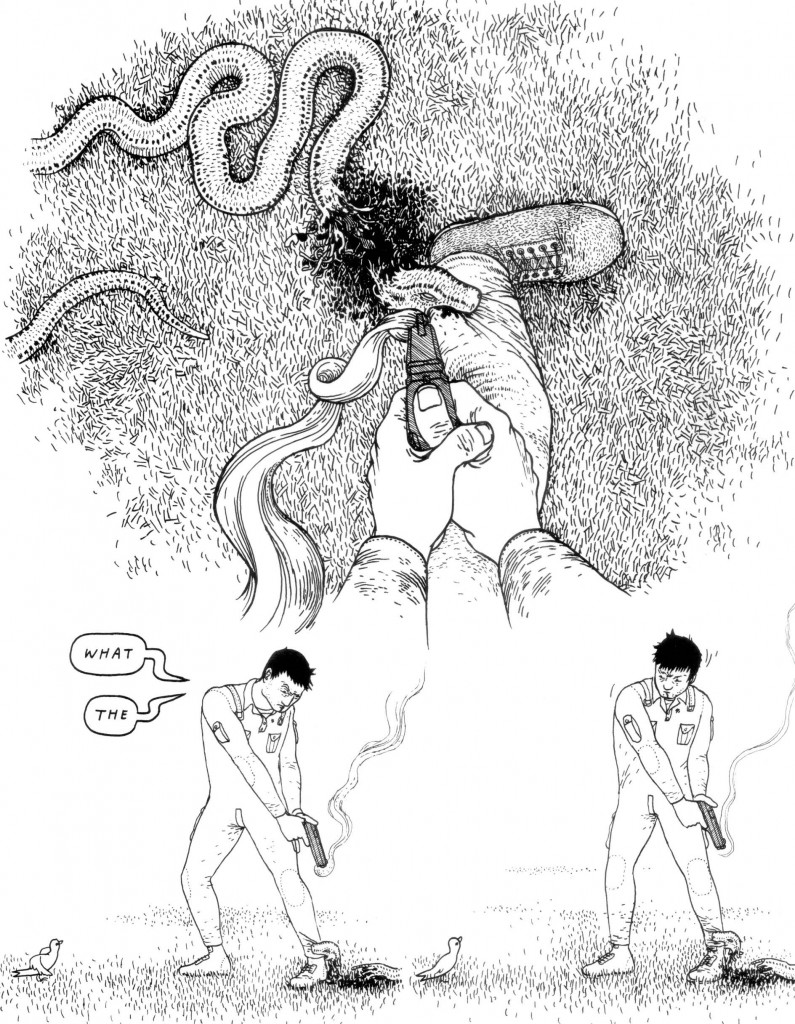

A review of Anders Nilsen’s Big Questions. Limited edition signed and numbered hardcover, 7.25 x 9.25, colour, 658 pages.

Synopsis: A group of finches begin to consider the form of their sustenance and the structure of their lives; both of these governed by men who take on the stature of gods. One is a worldly, hallucinating fighter pilot delivering mystery in the form of a bomb — impatient, anhedonic, and destructive. The other is an “idiot” who takes what he can from nature; giving and removing life with the mercurial judgement of deity. An old and a new testament. The birds begin to take sides in keeping with their intellectual dispositions. The former figure attracts a complex theology, the latter, almost simple faith, trust, and finally devotion. There is a war of the gods and a hopeful denouement. The birds end up where they started, finally settling the big question they began with. Or have they…

“Behold the fowls of the air: for they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feedeth them. Are ye not much better than they?”

Matthew 6:26

Those looking for an encapsulation of the ingenuity and promise of the 90s small press — that calculated rawness, that sense of adventure, that palm-sized aesthetic object — could do worse than read Ron Rege Jr.’s Skibber Bee-Bye. Anders Nilsen’s collected Big Questions ,itself a product of the 90s, re-imagines this for the new millennium — that slow, hesitating shuffle away from Fort Thunder and its adherents into a world of hefty Smyth-sewn tomes heavy enough to kill a small animal. This world is more laid back, engineered, and formal; as thick and traditional in its narrative as Dash Shaw’s Bottomless Belly Button (a younger cousin of sorts), yet more sprightly and clever, and difficult to envision in any form except comics.

This new edition of Big Questions is easily digested in a single sitting and is the only sensible way to read Nilsen’s work. The individual issues suffer from a certain brevity and disconnect wrought through drawn out publication schedules, yet remain ultimately necessary for those interested in supporting independent comics artists and their publications. It is, perhaps, only in this collected edition that the inter-species relationships of Nilsen’s comic thicken and caramelize, only here that the pitched battles acquire any degree of emotional tension, only here that the scope of the entire work can be appreciated.

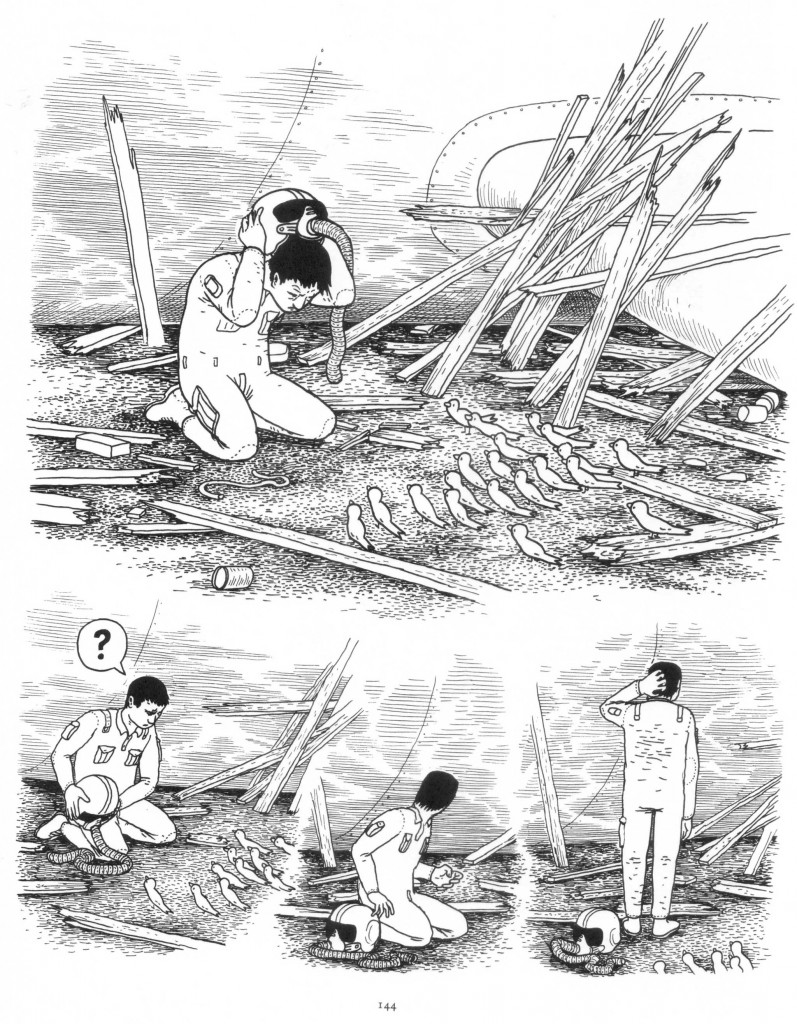

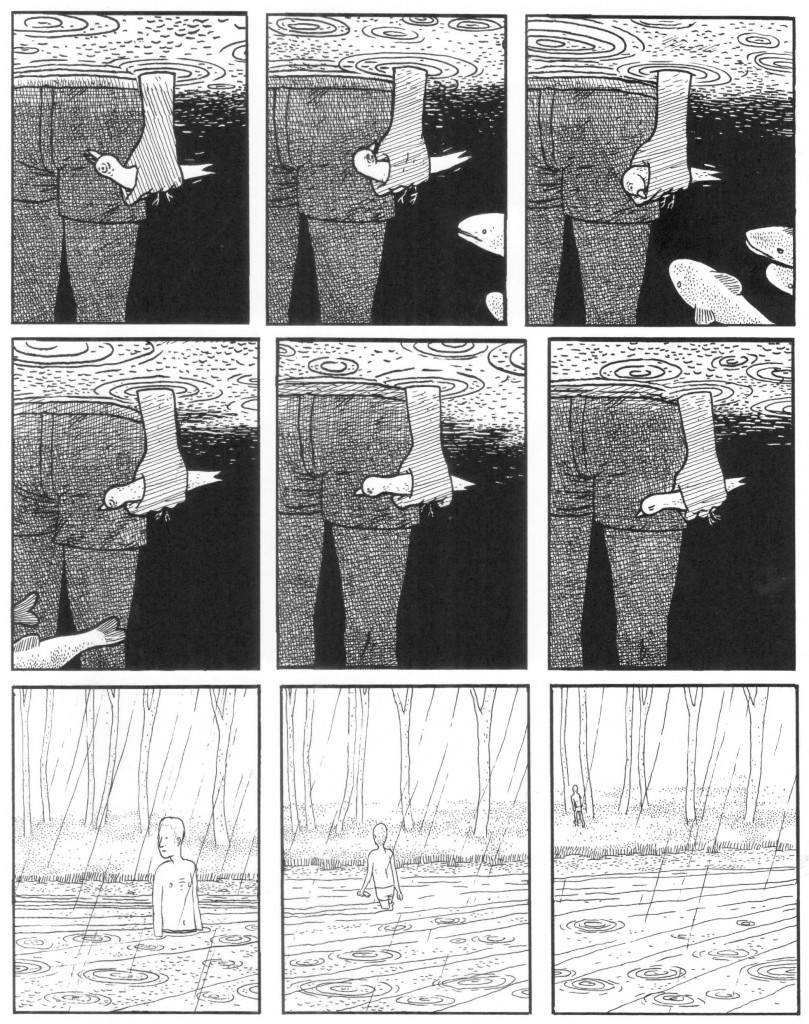

Nilsen describes the genesis of Big Questions some fourteen years ago in his afterword, recalling an artist’s workshop where a “very simple story…emerged [involving] a lost soldier in a barren landscape, a group of birds, and a plane crash”. He describes the process of learning how to draw comics over the course of this project, and that growth is clearly evident even within the first 100 pages of this collection. It is within these pages that we see ideas introduced and then discarded as they are found to be less useful (the somewhat clumsily drawn squirrels replaced by more vicious carrion eaters for instance); something we find not infrequently in comics which begin in a more freewheeling spirit before gaining concentration and more straightened purpose. Long dissertations give way to space and silence; static points of view are replaced by movement across panels and the use of the full expanse of the comics page; hesitating stippled backgrounds progress to detail and increasing complexity. All this mirroring Nilsen’s increasing confidence and conviction as a storyteller.

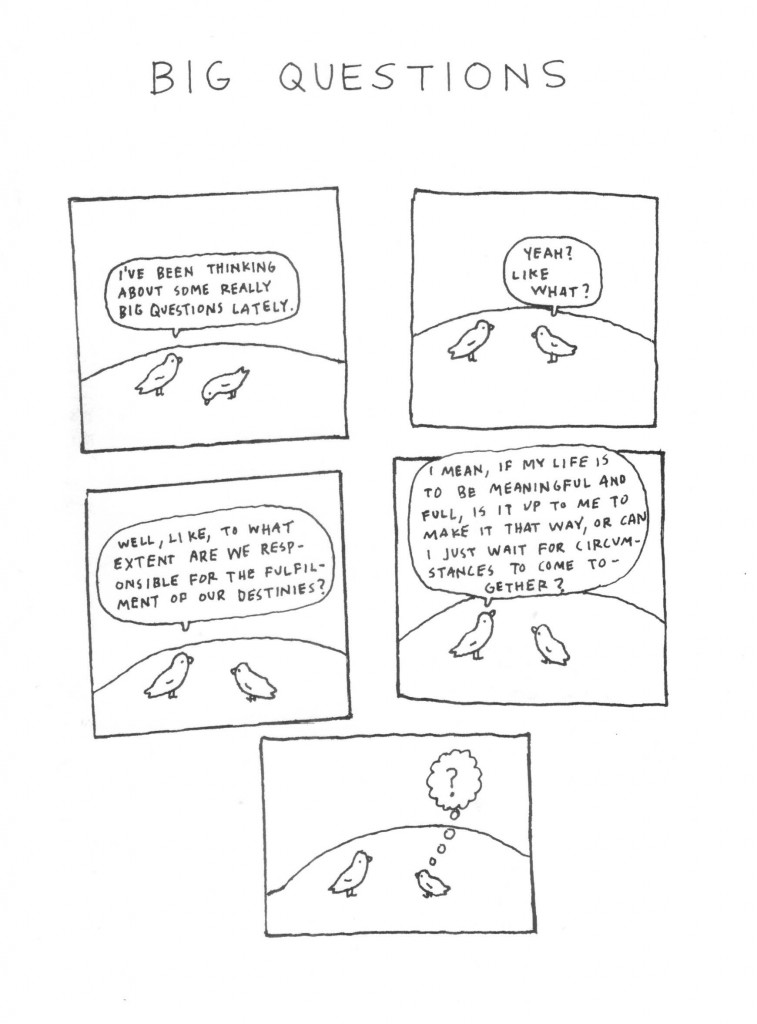

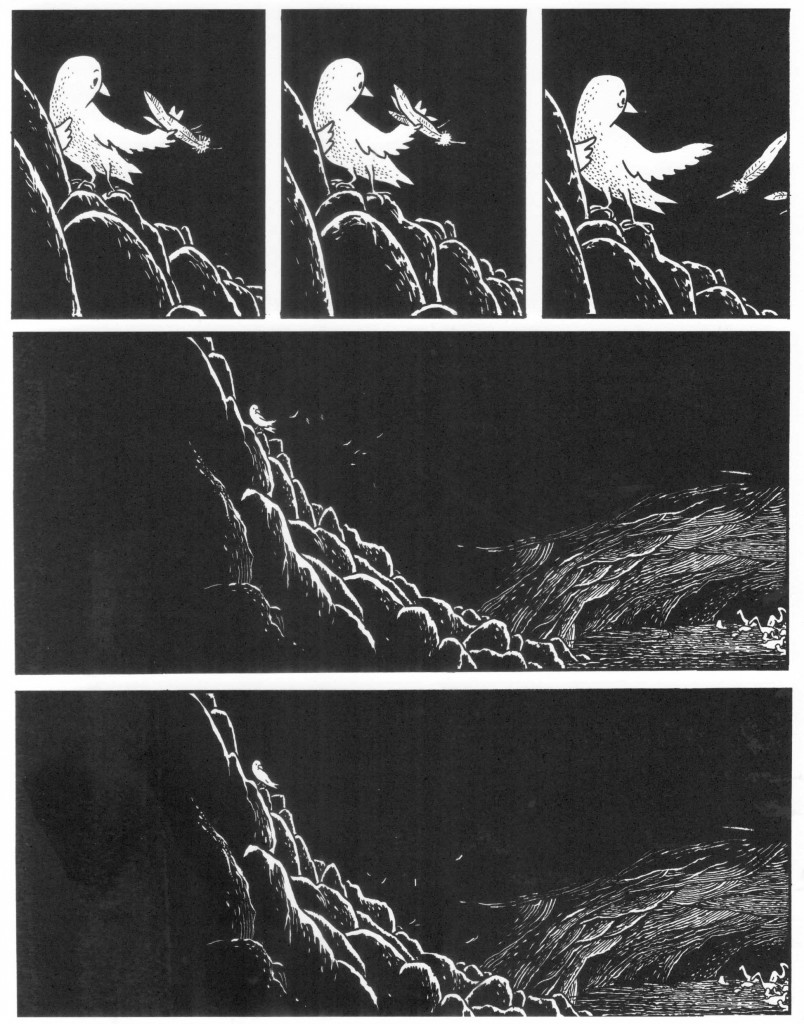

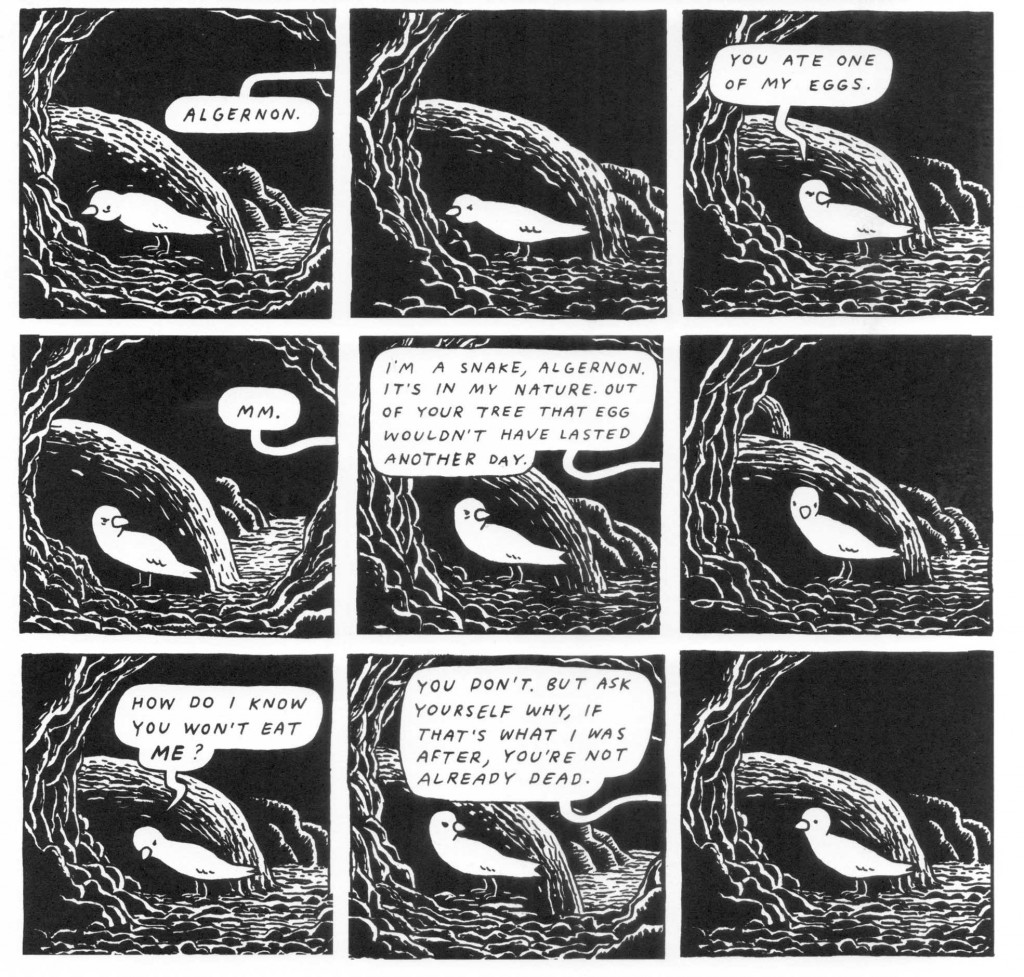

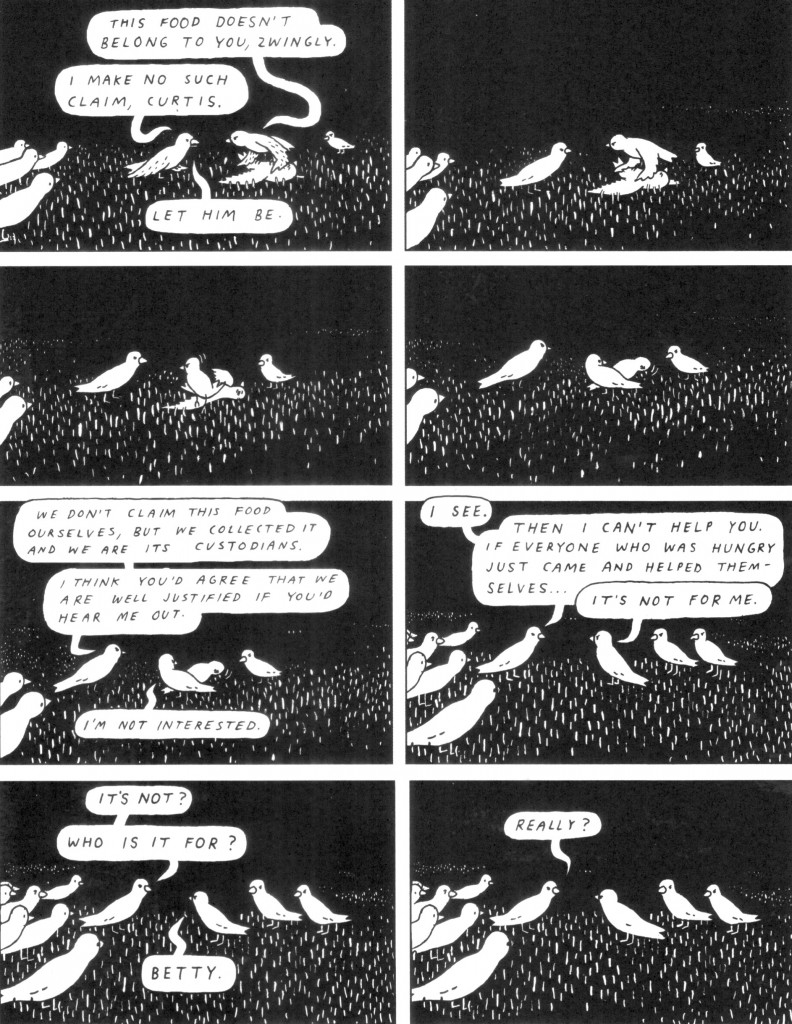

The “talking birds” come to Nilsen quite early and form the cornerstone of the early issues and chapters of Big Questions. The imagery seems at first to thrive on the curious irony of having birds consider impossible mysteries. The first of these (reiterated once again at the close of Nilsen’s comic) concerns nothing less than predestination and free-will.

[The first big question]

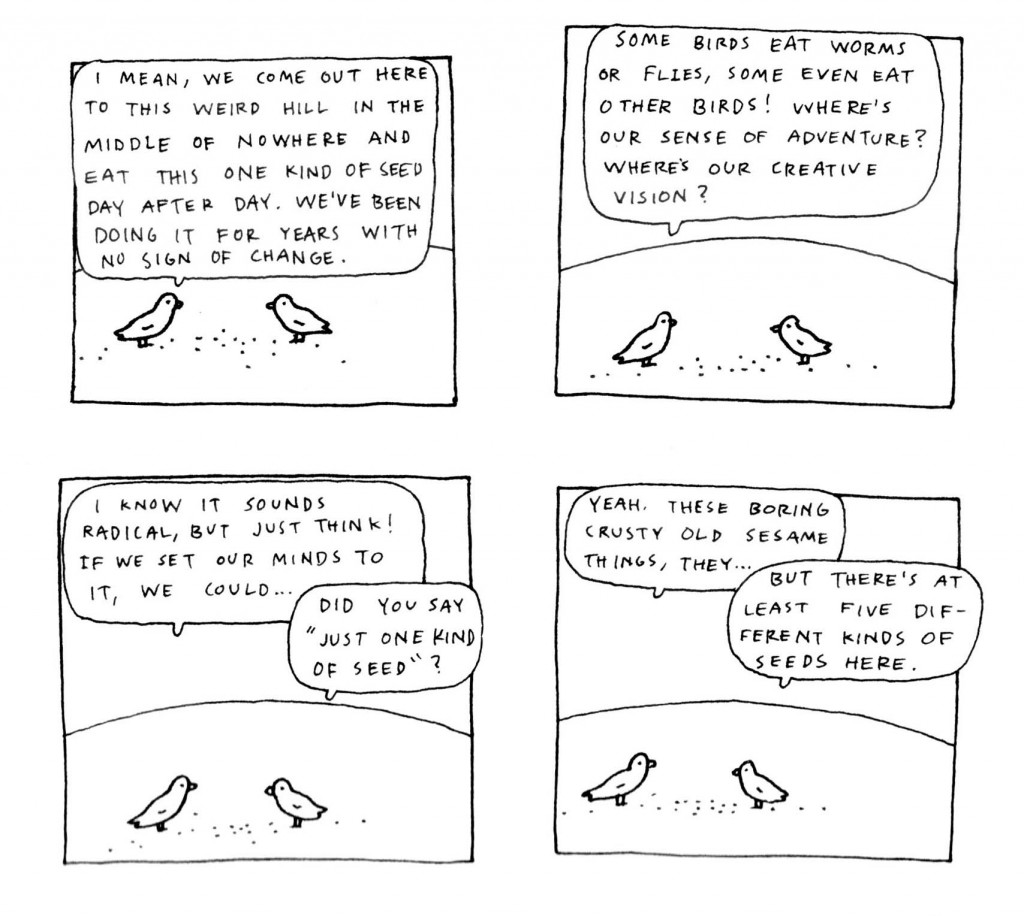

Crystallized ideas and inquiries are pressed on the reader through this act of reduction. Our own wants are seen in the light of specks of indistinguishable food; our destinies seen more clearly and simply in the threads of fate that envelop the humble life of birds.

[Food and Life according to the birds]

Nilsen’s comic is a fable and parable asking us to reflect on where we are. The simplicity with which these ornithological forms and the distilled elements of their lives putting into sharp focus our own frailties and needs. The forms are delineated with a few strokes of Nilsen’s pen and brush but their direction, posture, and deployment suggest compassion, anger, and depression.

“I kind of like the idea that they are, in a way, all the same bird, just reacting to different situations and contexts. The sameness of the birds was an accident in a way, but ultimately I decided to embrace it as part of the book’s content.”

Anders Nilsen in an interview with James Romberger

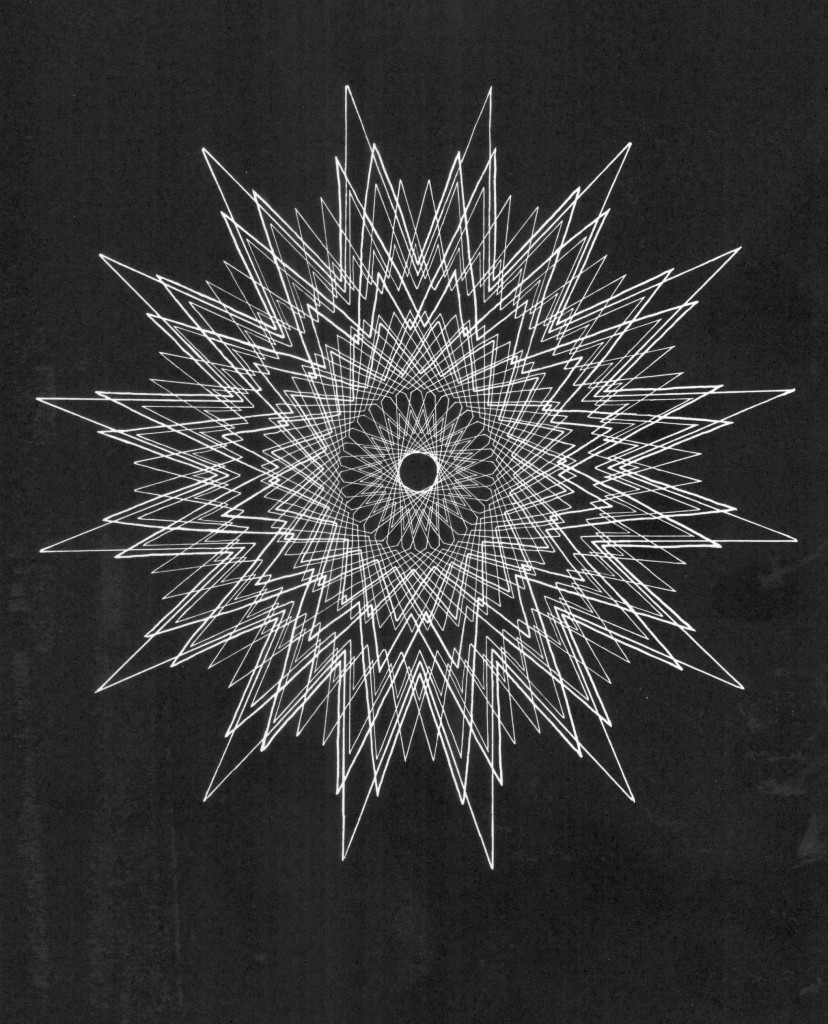

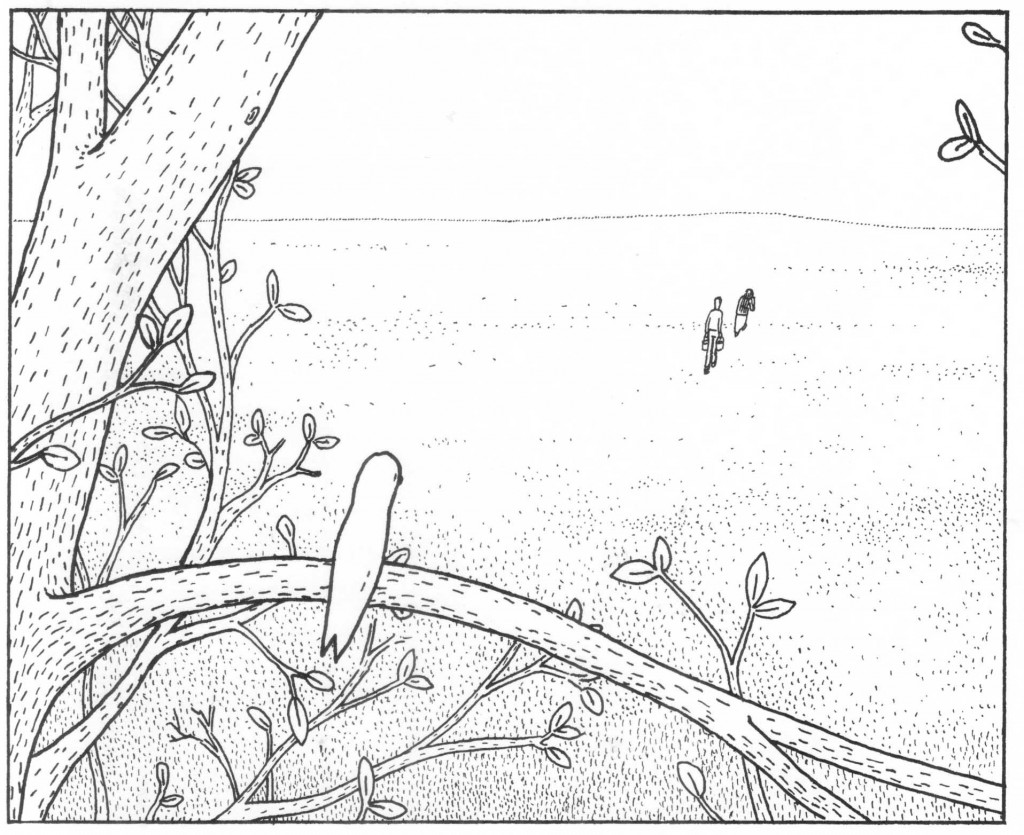

These quickly drawn shapes almost never suggest the identity of the speaker. This can only be determined through deduction, dialogue and setting; a device which instills that sense of allegory which is itself reinforced by the author’s use of emblematic marks and legend. All this slowly coalescing into a grand narrative of interweaving lines — planned, symmetrical, and increasing in complexity — suggesting forms like a star of Bethlehem or the “Ley lines” and fractals which cut through nature; the meandering flight of birds; the by-ways of fortune.

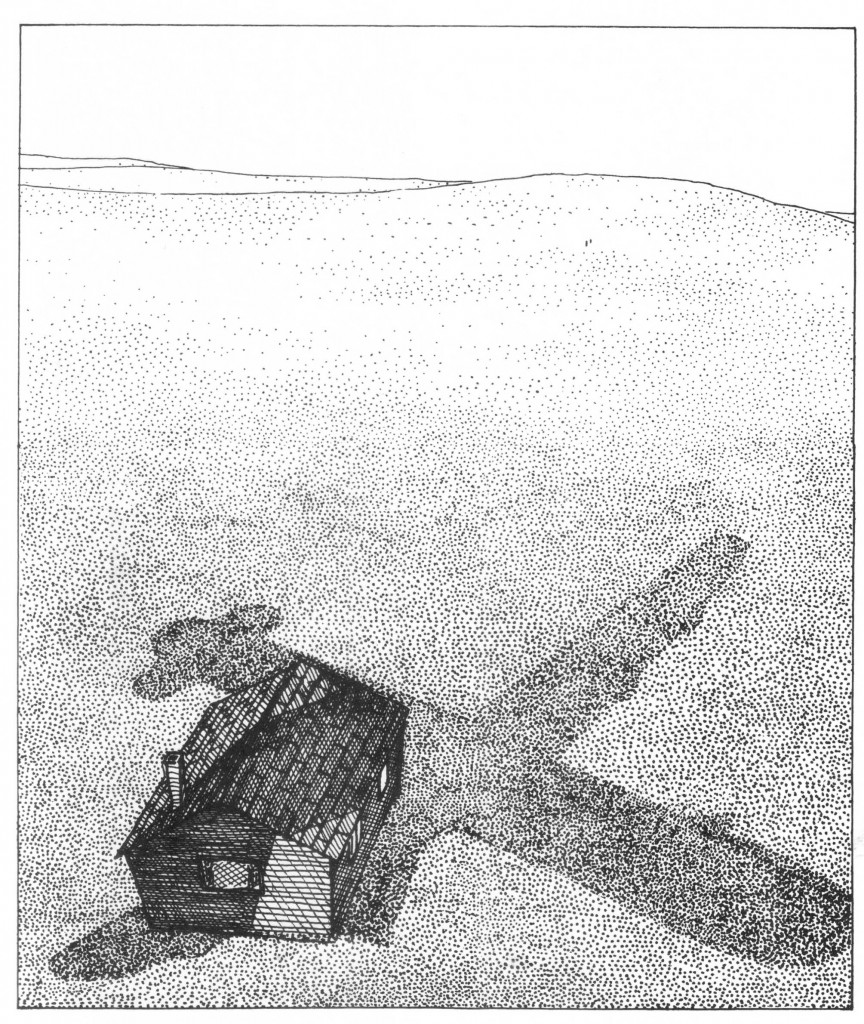

At one point, an airplane (a bomber) casts a dark shape over a pastoral landscape — an outsized shadow of the birds and hence ourselves.

Much later we find a short journey into the underworld and Orphic myth.

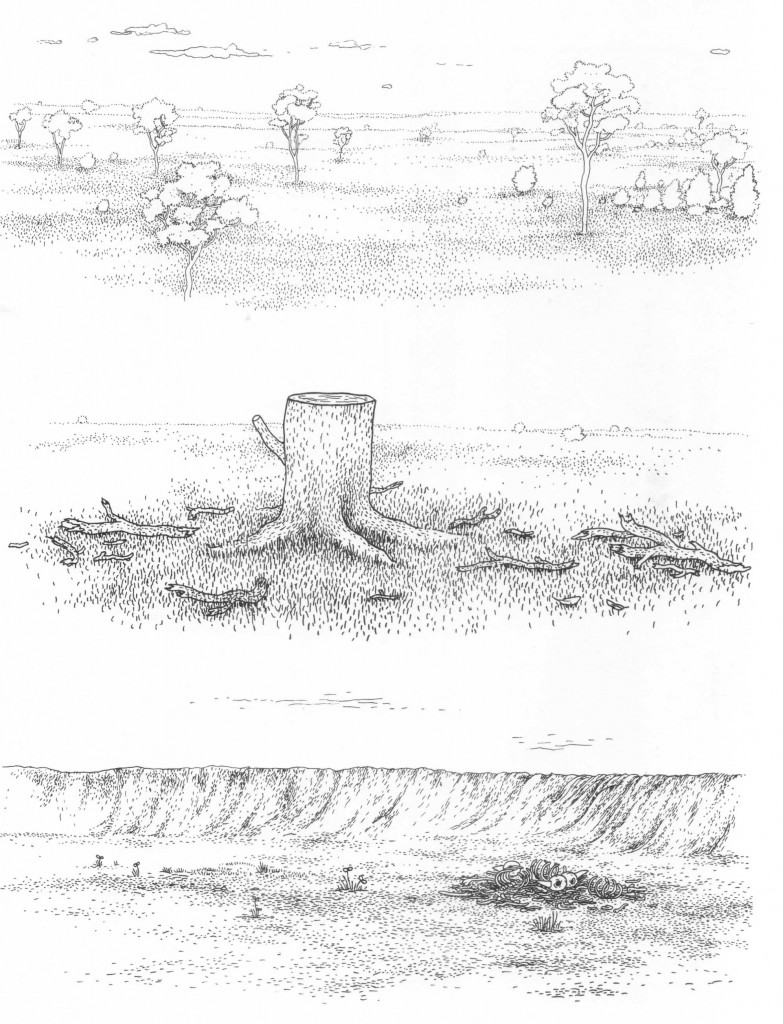

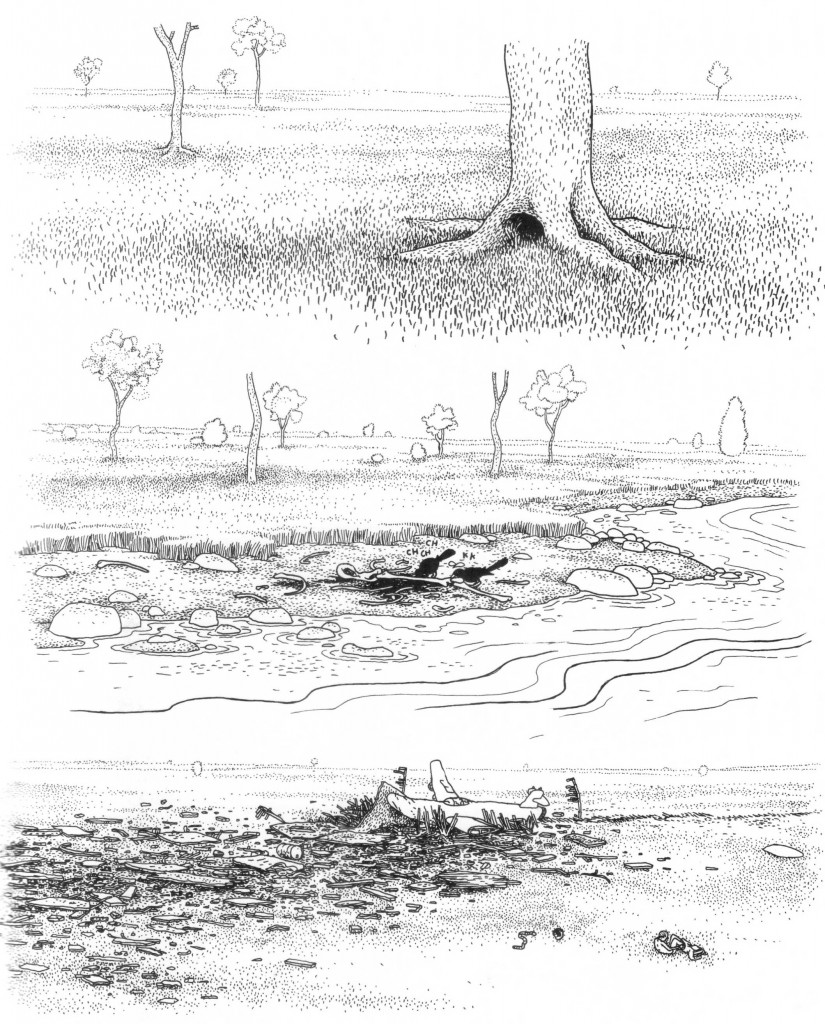

When Nilsen recalls the places and settings of his tale in the final pages of his work, we find both symbols and a microcosm: an Arcadian field; a fallen tree; a bomb crater containing the shadows and bones of the fallen scavenged by crows and wild dogs; a snake’s burrow guarding the entrance to the underworld; a river which is both the Jordan and the Styx; and life in cold relief.

Religious themes punctuate the narrative consistently and continuously. The leader of a group of Messianic finches is called Zwingly (presumably after the reformer Zwingli), the proselytizing concerning the new religion is done by birds identified as evangelists. It is a mystery play with birds (Betty and Charlotte) standing in for the faithful-doubtful women kneeling at the foot of the cross or waiting faithfully at the empty tomb. There is an aged and kindly reptile guarding the gates to the underworld…

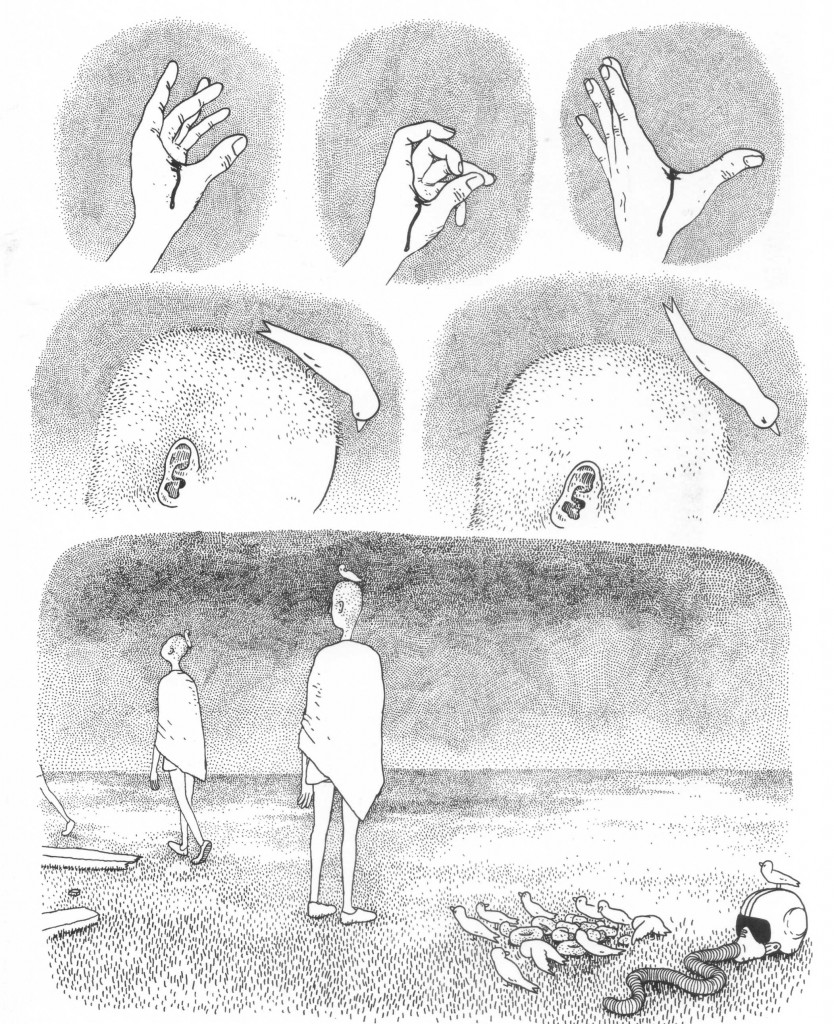

…and an erstwhile deity emerges like Wally Wood’s spaceman from the husk of a giant bird (a “miraculous visitation”) — a virgin birth; an Athena springing forth from the head of Zeus; a parthenogenetic celestial appearing before their eyes.

[“Jesus” by Wally Wood; “He Walked Among Us”]

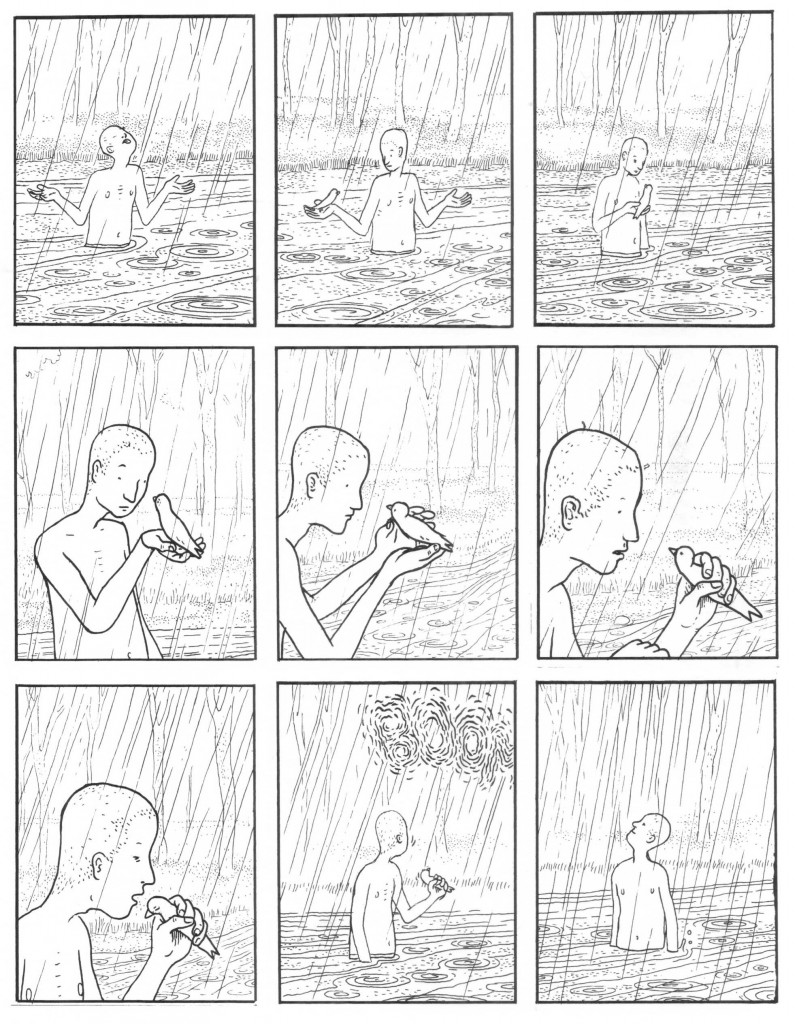

A centerpiece of this exploration is the Lazarene miracle surrounding a finch called, Bayle. Raised from the dead even as he is killed by his faith — that ridiculous and dangerous longing to be held in the hand of an unknown force.

“It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God” (Hebrews 10:31).

There are other correspondences. The biblical narrative suggests that Jesus tarried for 2 days after receiving word of Lazarus’ illness (“This sickness will not end in death. No, it is for God’s glory so that God’s Son may be glorified through it.”) only then starting for Judea and Bethany. And so it is in Nilsen’s narrative, where death is almost an act of capriciousness and, more than this, devoid of compassion. Here, the author suggests that both life and death come from the same source, one so distant and unapproachable as to seem to emanate from an imbecile, monster, or saint.

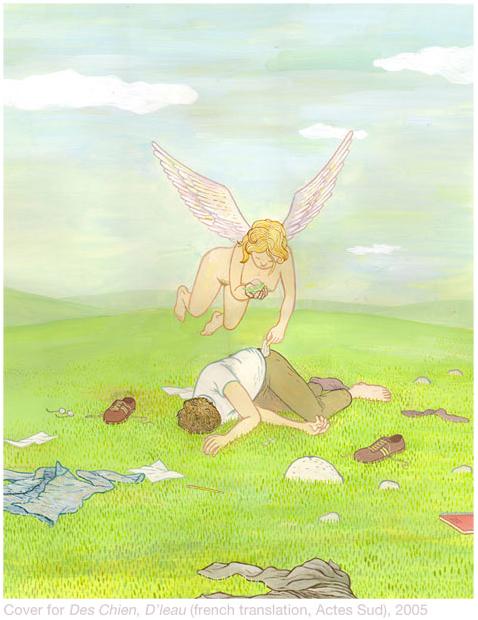

Nilsen’s standalone illustrations often depict wastelands, roadside accidents, and dumps. Disemboweled bodies centered in image and yet anonymous in their deaths; touched by some unseen pastel hand or angel; a vision of our fickle lives.

[Illustration work by Anders Nilsen]

Of course, Bayles’ death (a drowning) is made doubly significant for being a baptism from which he rises like the Holy Spirit above his messiah’s brow.

[Piero della Francesca’s Baptism of Christ]

The ornitho-Christological theme is pressed to its limit: a feeding or, perhaps, a preaching to the birds by St. Francis occurs at one point; and a latter day Elijah is fed by the same winged beasts at journey’s end.

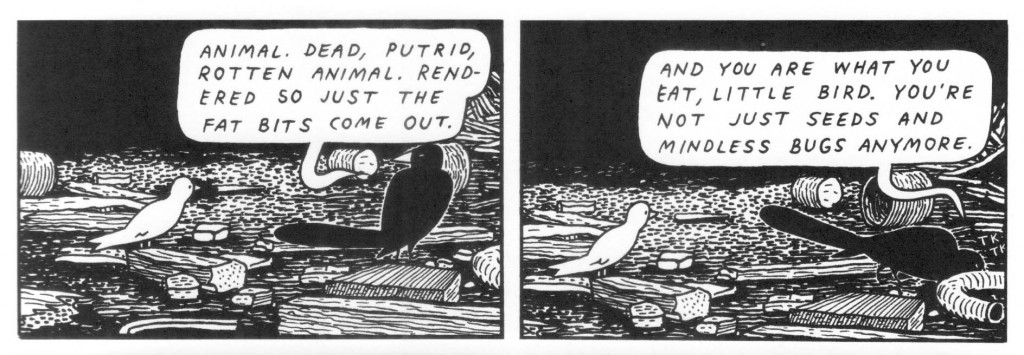

The doughnuts and crumbs upon which the finches feed become nothing less than the elements of the Eucharist, laced with the meat and blood of transubstantiation; a meal which is cursorily ridiculed as it has been through the ages.

Like Eurydice and her pomegranate seeds, the bread is tainted not only by innocence but war and regret. “You are what you eat, little bird.” proclaims a carrion crow,

Nilsen never answers the big question he begins with, only jabbing lightly at the fabric of existence. If there is an answer in his puzzle and construct, it is the answer provided by the lives which writhe and weave before us in his tale; now seen from a factual and atheistic distance. A world governed by intention, coincidence, accidents, and foolishness. We can see some similarities with the work of Kevin Huizenga in that artist’s own “sermon notes” comics, philosophical inquires, scientific discursions, and theological musings.

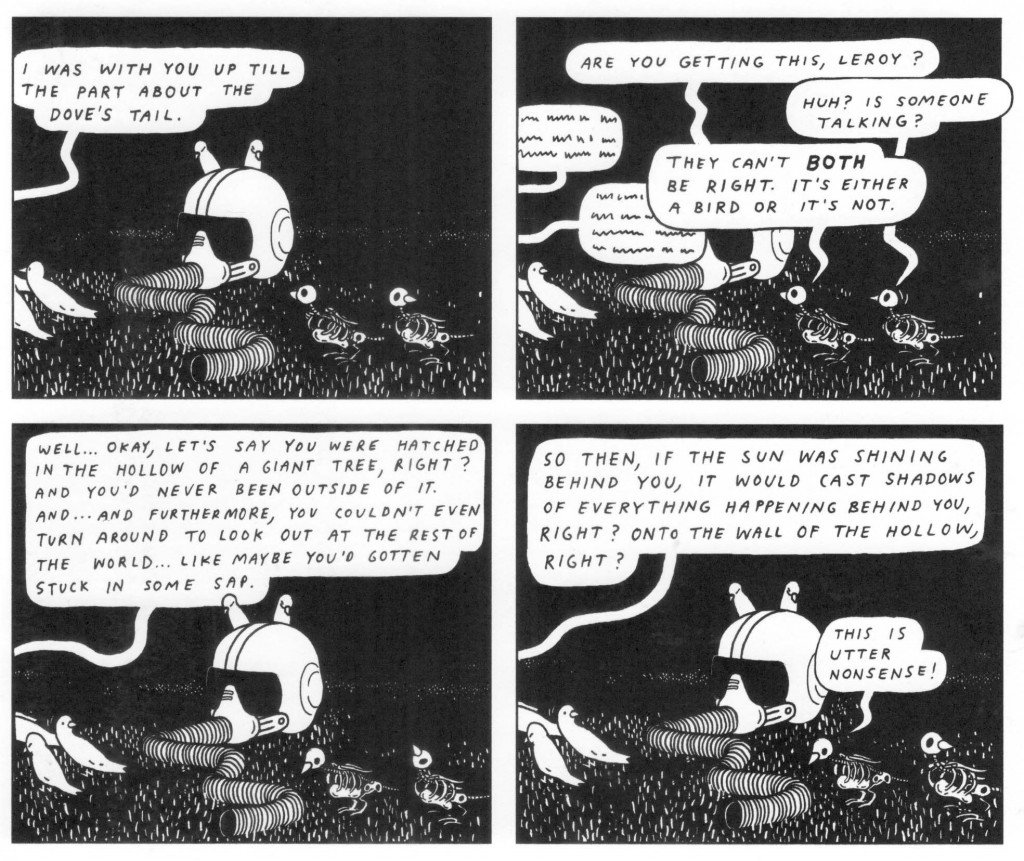

Plato’s Cave is for the birds

Neither is particularly dismissive but Nilsen is the true skeptic. He peppers his narrative with religious absurdities while occasionally leavening them with more kindly interpretation. His non-existent God is something which we feed and give life to, a concept which sometimes give us strength through blind chance and misplaced faith. As he states in his interview with Romberger:

“I think about that word, Asomatognosia, as a kind of metaphor for the religious impulse. I heard about the condition while listening to an interview with the neurologist Oliver Sacks. He described it as a condition where one loses one’s sense of ownership over a limb, usually an arm or hand…That sort of alienation from one’s own sense of control, our own agency, to me works as a kind of metaphor for the displacement of responsibility that a belief in the supernatural, or in god can sometimes entail. “

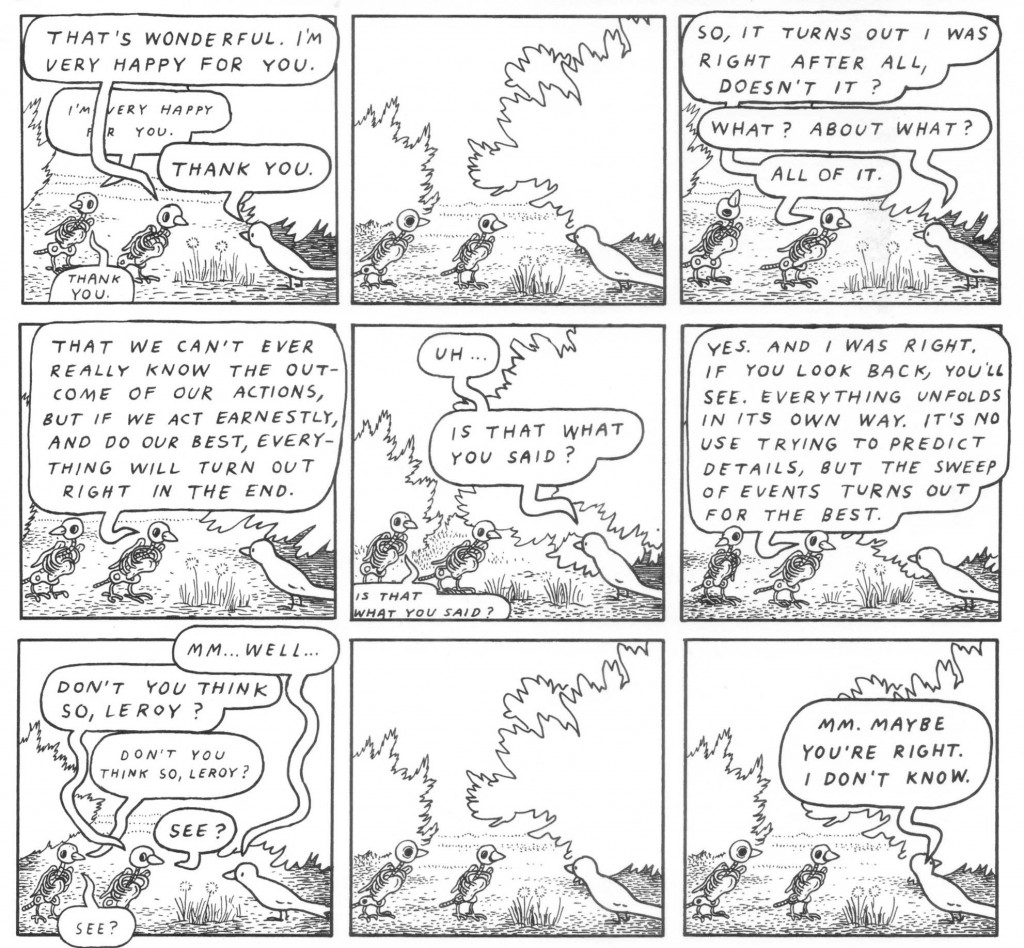

We can detect that appreciation for Sacks’ wry humor throughout this comic, not least in a skeletal evangelist reciting a Panglossian homily to a former friend.

“Everything will turn out right in the end…”

…and the triumph of worldly “faith” and enlightenment.

The flower pots arranged and rearranged making us more keenly aware of their fragrance and color; the investigations and queries handled broadly rather than in depth; removing mystery from life. Nilsen would be the first to admit this and does so in his interview with Matthias Wivel at the metabunker:

“Nilsen: No, I haven’t read a lot of philosophy…I’m just curious about the world. Most of what I read is non-fiction; not philosophy explicitly, but I’ve always been interested in those kinds of issues, the heart of the matter…So I don’t think I approach these issues with a lot of knowledge about what philosophers who dealt with them before me thought about them, I don’t have a strong grasp of the history of them, but they’re just interesting questions and I’m learning. Also, my grandfather, my mother’s father, was a Lutheran minister of a very universalist stripe, so I think that some of the issues that I’m interested in are theological and stem from that…

Wivel: Are you religious?

I’m not religious at all, but I’m interested in thinking about religious issues, the nature of the world, meaning, things like that.”

If there is a problem with Nilsen’s comic, it would be this marginal interest — not so strange and wonderful to behold as the belief bordering on insanity we find in films like Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice, and yet not so supremely intellectual in its contempt as to engage the reader’s mind fully. What remains is the emotional and aesthetic core of the narrative: the gradual mastery of form and narrative; the heat of battle; the sweetness of conversation; the pain of parting; and that sadness spoken through animals. And, perhaps, this is just enough to make us believe.

_____________________________________

Related articles

An interview with Matthew Baker at Nashville Review concerning his entire oeuvre.

An interview and introduction by James Romberger at Publishers Weekly. The initial discussion focuses on the spontaneity of the comics’ creation and its graphic design.

Matthias Wivel’s 2007 interview with the artist.

An interview at Comic Book Resources. “Using animals characters gives you a shorthand for personality and automatically connects them to some kind of symbolism. Birds are symbolic of transcendence or flight. Snakes have this history in Western culture, whether it’s the Garden of Eden or the way snakes are portrayed in Greek mythology. You get this extra material that just sits there in the background. You don’t have to be explicit about it but it can inform the story and inform the character.”

“Comics as a Spiritual Pursuit” versus “People Don’t Buy Comics” – Thoughts after SPX 2011

The Small Press Expo is really two festivals, simultaneous and inseparable but nonetheless distinct – the one where cartoonists talk to other cartoonists (and publishers and journalists and critics) about their work and their craft and their inspiration, and the one where comics fans and curious people come to collect mini-comics, buy compilations, fill sketchbooks, get autographs, see what it’s all about and meet those cartoonists. SPX cartoonists are exceptional people. And SPX is, ultimately, not so much about comics as it is about cartoonists themselves – cartoonists as a source of creative inspiration for each other and for the rest of us.

When I attended my first SPX, I had a vague grasp of the idea of art comics but I had read very little – Eddie Campbell’s “Fate of the Artist” and Dash Shaw’s “The Mother’s Mouth.” I read the Shaw because I was writing a regular books review column for a Virginia-based magazine and Shaw at the time was living in Richmond, so it fit my “local author” requirement. The Campbell was specially and insightfully selected as the “Right Way to Introduce Caroline to Art Comics” by a friend who resisted giving me comics to read until “Fate” matched up with the things I’d said I liked about literature. (It remains, as everybody here knows, one of my favorite books period, of literature or comics.) So I was primed for the notion that comics were Art, but nonetheless not quite prepared for the headiness of SPX.

That first SPX afforded me the opportunity to speak directly about art – not just comics, but art and writing and criticism as well – with cartoonists like Austin English and Nick Abadzis and Juliacks, and with critics like Gary Groth and Douglas Wolk, and it gave me the opportunity to hear really intelligent panel discussions about making art, featuring not only Nick and Austin but John Hankiewicz, and Tom Kaczynski, and C.F. and Kim Deitch. Those conversations, passive and active, were about comics on the surface, but for me, without a lot of comics reference points, they were every bit as much about art in general – about inspiration, about making yourself creative, about doing the work.

I’ve had a similar experience at every SPX I’ve attended since.

After this year’s show, when we were all coming down from the high, Charles Brownstein of the CBLDF commented that “if you let it, [SPX] will reorient you towards comics as a spiritual pursuit,” and the sentiment gets at exactly what’s always made SPX so compelling. Until I started writing for HU, the culture of art comics in my experience was the culture of SPX. And the culture of SPX is extraordinary, because of those extraordinary cartoonists – 300 or so of them – and the conviction and imagination they bring to the show. I love comics because I love SPX. And I love SPX because the cartoonists’ passion for comics is an airborne intoxicant everywhere you go during the festival. At SPX, the cartoonist is the medium, transmitting the force and effect of comics’ potential to everyone in the room.

I think most people who come to SPX experience at least some of that intoxicating excitement, and I think we recognize it as one of the festival’s most valuable assets – especially for getting neophytes like I was to care more about comics and what they have to offer. Recognizing it, though, isn’t enough — we have to get that excitement airborne before the festival, so that it arouses curiosity in people who wouldn’t normally come to a comics event. And we have to get it into media that reaches that audience locally.

Coverage of SPX within the comics blogosphere is always strong (thanks everybody!). This year, advance coverage of SPX in local media was much more extensive than in any previous year – and we had a packed floor on Saturday as a result.  That coverage was due, again, to cartoonists: the festival’s slate of high-profile guests was exceptionally strong this year, thanks primarily to Executive Director Warren Bernard’s months-long efforts with publishers and individuals. But the coverage goes into something of a vacuum, because most non-comics readers, including many journalists, have little to no frame of reference when they see an article about alt-comics. Mainstream media outlets, even the indie alt-weeklies, aren’t attentive to the books and cartoonists through the year (they often don’t really do “arts” coverage at all.) Non-comics readers aren’t primed to think of comics as a medium rather than a genre; they don’t get historical references; they have different expectations from people who are already in alt-comics’ core niche. Editors either don’t see comics coverage as relevant, or they see it as relevant only for their calendar/events section. The good editors get someone who is “in the know” about comics to cover SPX – but then that skews the coverage toward the existing niche demographic.

That coverage was due, again, to cartoonists: the festival’s slate of high-profile guests was exceptionally strong this year, thanks primarily to Executive Director Warren Bernard’s months-long efforts with publishers and individuals. But the coverage goes into something of a vacuum, because most non-comics readers, including many journalists, have little to no frame of reference when they see an article about alt-comics. Mainstream media outlets, even the indie alt-weeklies, aren’t attentive to the books and cartoonists through the year (they often don’t really do “arts” coverage at all.) Non-comics readers aren’t primed to think of comics as a medium rather than a genre; they don’t get historical references; they have different expectations from people who are already in alt-comics’ core niche. Editors either don’t see comics coverage as relevant, or they see it as relevant only for their calendar/events section. The good editors get someone who is “in the know” about comics to cover SPX – but then that skews the coverage toward the existing niche demographic.

The problem of the expanded versus niche audience is of course something comics deal with all the time and in many contexts. On a panel devoted to “Navigating the Contemporary Publishing Landscape” (watch online at the SPX website), Fart Party cartoonist Julia Wertz, discussing her experience publishing Drinking at the Movies with Random House, commented that “what big publishers do is they just throw a lot of shit at the wall and they want something to stick, and comics don’t stick because people don’t buy comics. So the problem was that they put out this book and they had no idea how to market it, and I’d say ‘you need to send a copy of this book to The Comics Journal or to Tom Spurgeon,’ and they were like “what’s that?’…They were really nice, but they had no idea what to do with this book.”

I sympathize with those people at Random House, trying to sell mass general audiences a comic. The advantage of a press like that is their ability to put your book into the hands of a very wide audience. But it’s really hard to get across to the wide world of non-comics readers why a comic or a cartoonist matters. So many of our answers about why comics matter refer back to medium-specific, historical or nostalgic, comics-insider frames of reference that are largely meaningless to that non-comics reader. If your audience is really those people who already read TCJ and Tom Spurgeon, if your comic is made for comics insiders, then Random House’s broad reach honestly becomes a disadvantage. Wertz is surely right that comics insiders are the most likely people to buy her book and that the Comics Internet is the best place to market a comic. But things stick when there’s an affinity between them, so the question jumps out — is the audience of people currently reading the alt-comics Internet, the audience already familiar with alt-comics creators and vocabularies, the audience of people prepared and persuaded to consider mechanically reproduced comics as postmodern objets d’art, really large enough to support, economically and artistically, the critical mass of cartoonists needed to keep art comics and cartooning vibrant and vital as an expressive medium? Or do we have to build an affinity between comics and those expanded audiences, who may never be “comics insiders”?

One of the best things I did at SPX was talk to occasional HU commenter — and Ignatz winner for Promising New Talent! – Darryl Ayo Brathwaite, who has really thoughtful opinions about this topic. Darryl commented that “indie comic insiders tend to buy the critically acclaimed stuff, and the indie comic browsers tend to go for stuff that doesn’t get Comics Journal acclaim necessarily, but has a fairly easy hook.” An easy hook helps people manage the noise: “conceptually simple stuff appeals to people’s sense of wonder as well as to their sense of needing manageable answers in a room full of noise, both audio and visual.” I think he nails those “comics-civilians” and their buying behavior, but I think he also nails the essence of PR: identify and convey the hook, simply and directly enough that the message gets there in just a few seconds.

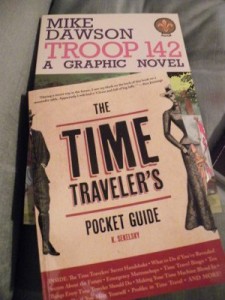

The truth, though, is that comics insiders get overwhelmed by noise too. And a catchy summation can help people grasp the value of a conceptually sophisticated book. It’s not either/or, really — conceptually simple or complex — what stands out most to me in Darryl’s observation is the importance of making people care, quickly and easily. As a frequent purchaser of both books and visual art, I often get stymied by art comics that don’t have good cover blurbs or creator bios. Sometimes it’s just plain impossible to tell what I’m holding without Googling it — or reading it. For a mini-comic, you just buy it anyway, because it’s $2, it’s handmade, and it looks cool. But it’s harder to rationalize the gamble for a $15 mass-produced book, and for me, impossible once the book costs $35-40. At a table in a noisy room, the blurb is the most immediate way to convey to a potential reader why the book matters enough to spend money on it. Fantagraphics’ blurb for Cathy Malkasian’s Temperance is excellent, just right for making the book jump out to a casual browser (even though they omitted an artist bio.) K. Sekelsky did a terrific job in one sentence on her illustrated book The Time Travelers Pocket Guide. Secret Acres’ compilation of Mike Dawson’s Troop 142 uses a catchy quote to strong effect.

But, those are narrative books. Tom Neely’s beautiful and conceptually challenging book The Wolf, in contrast, doesn’t have a blurb at all. It’s is a wordless comic, and I imagine it doesn’t have a blurb for the same reasons lots of wordless, “art-focused” comics don’t have blurbs: partly a) because it would visually disrupt the cover, but mostly b) because blurbs generally assert interpretations, and art-focused comics tend to value openness of interpretation, “make of it what you will.” I bought it because Charles Brownstein recommended it, but without his insider intervention I’d probably have passed over it: it’s visually arresting but it’s not really quite my thing (body horror and no prose). Charles, though, captured my attention — he essentially narrated a cover blurb. He got me past my first impressions and convinced me that the book matters, that it has something to say.

I know this suggests questions about whether comics are ontologically and commercially more like books or visual art, and raises philosophical issues about the Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Comics are Art — but they’re an art that hides quietly on the bookshelf, unlike the oil painting over the piano. Does thinking of comics as art objects move them toward kitsch because of the status of reproducibility in the comics medium, or do books where the art takes center stage problematize the categories of kitsch and art, including allo- and auto-graphic permeability and the subjectivity of interpretation? Anybody who has talked to me about art knows those type of questions excite me, and I think the extent to which comics challenge our notions about materiality and value does influence why people don’t buy comics.

But I also want every exhibitor at SPX to sell out of everything they bring. Promotion — whether at the festival level or the individual level — lives in that realm of hooks and pitches, not at the level of critical ontology. The kind of hook that appeals to a comics-civilian browsing at a festival isn’t really that far from the kind of pitch that appeals to a mainstream journalist skimming through an inbox of pitches. Part of the mission of comics PR, I think, should be to balance the valuable and motivating intimacy of comics’ community of insiders against the need to identify accessible and relevant hooks to promote cartoonists and their books successfully to an outsider public.

It’s not a ready balance. Those outsider publics rarely think in terms of medium; they think in terms of content. In the case of film and fiction and television, each medium has many disparate markets and target demographics that align more with the genres and styles and content available in all of those media than they do with any medium itself. But comics is both a single medium and, to a great extent, a single market. Mainstream comics readers are more likely to buy and read the comics at SPX than are people who have no ties to comics at all. But those outsiders do have commitments to chick lit or procedural drama or postcolonial narratives or feminist cinema. To appeal to outsider publics and expand the audiences who read comics, comics PR has to find the places where the content and genres and styles of the comics medium overlap with those disparate markets. The biggest challenge is appealing to those content-oriented markets without sacrificing what is so joyful about the medium-driven community we have now.

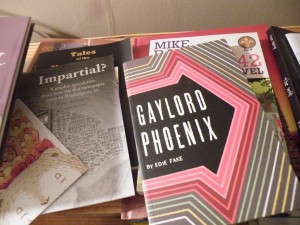

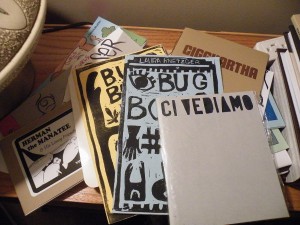

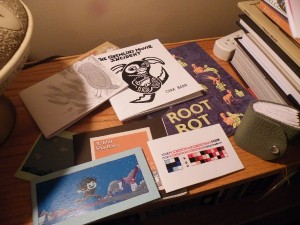

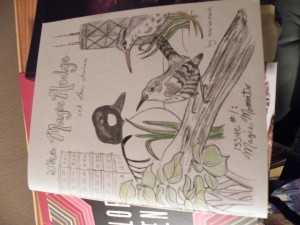

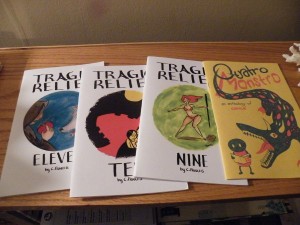

Unfortunately, I haven’t had a chance to read anything I bought at SPX, and I was only able to spend about an hour in the exhibit hall. So here, until I have a chance to process a little, are some photos of what I bought. They’ll get a little bigger if you click on them; mouse over them to see cartoonists’ names and titles. Some things I wanted to buy and missed, like Darryl’s comics, and L. Nichols’ beautiful work, and many others on Rob Clough’s list of must sees. I also didn’t make it to all the Ignatz nominees’ tables. For those of you who were there, please tell me in comments what else I missed!

Utilitarian Review 9/24/11

On HU

Vom Marlowe discussed Avatar: the Last Airbender.

I talked about Delta Swamp Rock, race, and the South.

I had an essay on the Black Eye Anthology, Johnny Ryan, and black humor.

Sean Michael Robinson on trolling natural disasters and the will of God.

I review Miranda Lambert’s pop country album Revolution.

Richard Cook on Giallo, violent Italian crime films.

A shoulder-shrugging country mix download for your listening pleasure.

I discuss race and the television show heroes.

And finally, I consider DC’s sexism and wish the company would just go out of business already.

And the Featured Archive post this week discusses fashion, fine art, and ontology.

Utilitarians Everywhere

At the Washington Times I sneer at Pearl Jam Cameron Crowe’s new documentary about same. Pearl Jam fans in comments freak out. You’d think I’d insulted Art Spiegelman or something.

At Splice Today I talk about Thelma and Louise and Women in Prison films.

And also at Splice Today I review Balam Acab’s latest effusion of New Age hipness.

Other Links

Archie Out of Context tumblr courtesy of Erica Friedman.

Charles Reece has a great essay on whiteness in Cowboys and Aliens and Attack the Block, part of the Pussy Goes Grrr Blogathon.

Michael Dooley interviews Percy Crosby’s daughter.

The Atlantic has a good article about K Pop taking over Japan.

Tessa Strain on the new Wonder Woman reboot.

C.T. May on Playboy Magazine.

TCJ with a big Johnny Ryan interview.

Slate with an article on the economics of being a fashion model.

Can’t Get No Worse

I have bought zero (0) DC comics in the last…um…well I’m not sure how long. (Unless you count Tiny Titans. Does that count?)

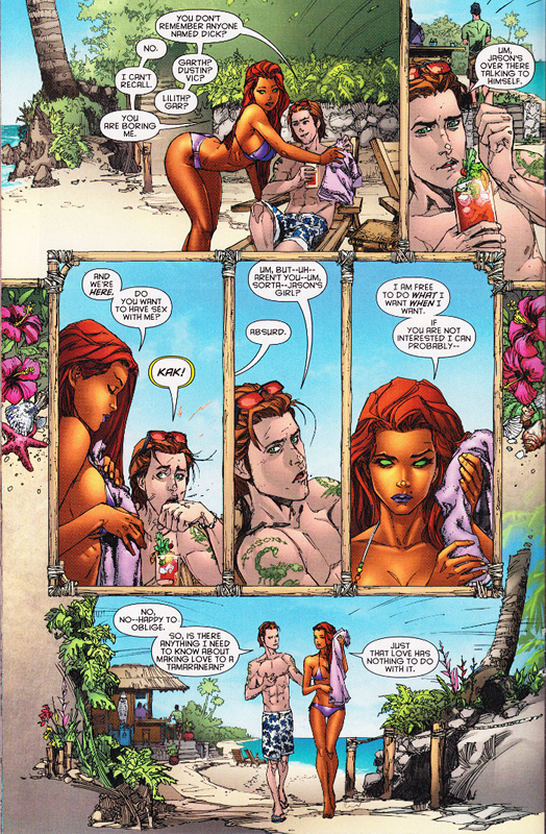

Anyway, the point is, I haven’t read any of the new reboot titles. Nonetheless, I surf the internets, and the new (new!) issue of Red Hood and the Outlaws appears to have really gone above and beyond and then through the basement and into the pig trough in its pursuit of the absolute, uncontested, nadir of idiotic giggling fanboy “I have never seen a woman but occasionally I wipe my dick with my four-colored friends” sexism.

But the one glimmer of goodness here is that DC’s idiocy has prompted a good bit of entertaining blogosphere commentary. For example, this from Graeme McMillan at Newsarama.

That’s right, fanboys! You liked it when Starfire wanted to jump into bed with Robin way back when they were in the New Teen Titans together? Well now she’s a sex-hungry warrior bimbo who not only can’t remember her ex-boyfriend, but can’t tell men apart so she’ll sleep with them all! That’s, uh, definitely the reboot that some people were potentially wanting to see! Maybe! Possibly.

Kickpuncher over at fempop is even more amusing.

Scott Lobdell gives his audience, his industry, possibly his entire gender the finger and says “Oh no, you motherfuckers. That’s not your fantasy. Your fantasy is a woman that will literally have sex with you just for existing. No woman with any standards, no matter how low, no matter how forgiving, could possibly be attracted to you, so here’s your new sex object—a brain-damaged goldfish with a rack. And you’re such a scared little boy, so afraid of commitment in even your own pathetic fantasies, that you’ll run away from a ‘clinger’ even if she’s as gorgeous, charming, and supportive as the woman Starfire used to be. You can’t bear even that slight chance that she’ll make you move out of your parents’ basement, get a real job, and make something of yourself. So I’ll cater to that too! Not only doesn’t she want a relationship, she won’t even remember you! That’s what you want in the end, isn’t it? A vagina-shaped goldfish! Look upon your lust, ye nerdy, and despair.”

Laura Hudson at Comics Alliance is more sober.

Most of all, what I keep coming back to is that superhero comics are nothing if not aspirational. They are full of heroes that inspire us to be better, to think more things are possible, to imagine a world where we can become something amazing. But this is what comics like this tell me about myself, as a lady: They tell me that I can be beautiful and powerful, but only if I wear as few clothes as possible. They tell me that I can have exciting adventures, as long as I have enormous breasts that I constantly contort to display to the people around me. They tell me I can be sexually adventurous and pursue my physical desires, as long as I do it in ways that feel inauthentic and contrived to appeal to men and kind of creep me out. When I look at these images, that is what I hear, and I don’t think I even realized how much until this week.

And I’m tired. I’m so, so tired of hearing those messages from comics because they aren’t the dreams or the escapist fantasies or the aspirations that I want to have. They don’t make me feel joyful or powerful or excited. They make me feel so goddamn sad that I want to cry, because I have devoted my entire life to comics, and when I read superhero books like these I realize that most of the time, they don’t give a sh*t about me.

I have been doing this for a long time, now. I have lived in the neighborhood of superhero comics for a long time. And frankly, if this is how they think it’s ok to treat me when I walk down the street in a place that I thought belonged to me just as much as anyone else who lives here, then I’m not sure I want to live here anymore.

I think Laura’s got the right idea…but I hope she moves quickly through grief and on into indifference. Because nobody should be crying over contemporary mainstream superhero comics.

And the reason nobody should cry is because Laura’s absolutely right. Mainstream comics don’t give a shit about her. Criticizing DC is worthwhile because pointing out sexism is worthwhile and good writing is worthwhile and most of all because these morons deserve to be insulted. But hoping that Dan Didio is going to give a fuck about feminist complaints is like hoping that the coal industry will, after serious discussion, suddenly decide that solar energy is the future. You can teach an old dog new tricks, maybe, but you can’t turn an old dog into a penguin.

I’ve said this before more or less (most recently here) but maybe it bears repeating. Superhero comics are a tiny, niche market. Within that market, women are a tiny minority (10% at best, from the figures I’ve been able to find.) The audience for superhero comics is the small rump of 30-year-old plus men who have been reading superhero comics for 20-plus years and still want to read about the child-oriented characters of their youth — only, you know, in a kind of skeevy, adult way.

Now, maybe you read superhero comics, and that doesn’t describe what you want from them. Which is cool — but it’s worth realizing that you are in the minority (among superhero comics readers. You’re among the vast, vast majority in terms of the rest of the world, obviously.)

If the reboot makes anything clear, it’s that the core audience remains the core audience. It’s not going anywhere. This is what mainstream superhero comics are.

The point being, the best possible outcome here is not that DC starts writing better stories. It isn’t that they become more diverse. It isn’t that they hire more female creators. The best possible (note I said “possible”) outcome is that these shitheads finally, finally go out of business.

And if they do, you know what? It won’t be the end of comics, because there are lots and lots of comics. It won’t be the end of superheroes, because they’ll go on in other mediums…and, for that matter, there are lots of superhero comics not by the big two (many of them made in Japan). It won’t even be the end of your favorite characters, I wouldn’t think — there’ll still be back issues. If you love Starfire you can reread those old Teen Titans comics, which certainly had their problems…but at least Marv Wolfman seemed to care about Starfire the way creators care about their characters, rather than the way fanboys care about the fetish object they’ve been wanking to for decades.

And if you must, must, must have new Starfire content…well, write it yourself. Your fan fiction isn’t going to be any worse, and certainly won’t be any less “valid”, than the crappy corporate fan fiction DC is churning out. DC doesn’t own your characters, they don’t own your dreams, and they don’t own your aspirations. What they do own is some copyrights, and no doubt those will only be removed with force from their cold, dead corporate hands. Which is all the more reason to wish those cold corporate hands extinct. Maybe, if we’re very lucky, this reboot will be looked back upon not as another failed, stupid, embarrassing detour, but as the beginning of the end.

Have To Admit It’s Getting Better

Heroes attempted to turn comic books into television. It got the superpowers; it got the convoluted, incoherent plots; it got the (Marvel-era) whining and repetitive self-actualization. It’s got really hideous looking art for the comics-within-the-TV-show, courtesy of Tim Sale and Alex Maleev (both of whom have done decent work in other contexts — fulfilling another mainstream tradition of consistently coaxing horrible aesthetic performances from talented people.) It’s got the tedious snickering self-reference, epitomized by main character, Hiro, who announces with great fanfare “It’s Wednesday!” and then goes longbox diving to find secret clues to predicting the future (and if that sounds ridiculous, that’s only because it is). Heroes even channels some of mainstream comics dunderheaded, nerd-in-the-basement misogyny by making its two main female characters a cheerleader and a sex worker. “Save the fetish, save the demographic!”

But, despite all that, Heroes fails catastrophically to follow comicdom in one important respect. Traditionally, in comics, mutant genes, power rings, radioactive accidents, and tragic inspirational parental death are all apportioned out almost exclusively to (a) Americans, (b) people with white skin, or most often, (c) both a and b.

This works okay with comics since nobody reads them. But with television you run the risk of actually offending someone if you pretend the entire world is monochrome — which is why John Stewart gets to be Green Lantern on all the cartoons. It’s similar to the way in which businesses will trot out their one black executive (or secretary, if they’re that pitiful) for public encounters in a desperate effort to pretend that they’re not…well, what they are.

Heroes does better than tokenism, though. Its cast is thoroughly integrated in a way that mainstream comics have almost never been. Besides characters from Japan and India, the first season also featured a Hispanic-American hero, two African-American heroes, and an important African-American supporting character. The story is also notable for having multiple interracial romances — including that rarest of pop culture phenomena, an Asian-male/Caucasian-female pairing.

So is Heroes a glimpse of a possible comics future? A future in which DC doesn’t randomly insult entire continents full of people? One in which Marvel doesn’t say…”Hey! Black Panther! Storm! They’re both black! They should get married!” A future in which a black man under the Spidey mask doesn’t cause anyone to freak out even a little bit?

Maybe it is. But if Heroes is the future, there’s not much cause to celebrate. Because, while the show certainly has lots of minority characters, it treats those characters with systematic and concentrated stupidity. White characters are politicians and cheerleaders and single moms and cops; — “normal” people. Hispanic Isaac Mendez (Santiago Cabrera), on the other hand, is a junkie. African-American D. L. Hawkins (Leonard Roberts) is a criminal. Mohinder Suresh (Sendhil Ramamurthy), an Indian scientist, is drafted to spout pseudo-mystical gibberish at the beginning of each episode because Eastern peoples are all spiritual and shit. And, of course, the show’s black characters have a disturbing propensity for ending up dead.

Most depressing, though, is the handling of Hiro (Masi Oka). Presented as the moral center of the show, Hiro is less a person than a mismatched pile of Japanese stereotypes. He works at an oppressively homogeneous Japanese company lifted from paranoid 80s American nativist film; he gets a samurai sword and is taught to use it by his improbably adept father; he obsesses over pop culture like an uber-nerdy otaku. The fact that his English is not so great is used as an excuse to present him as an intellectual and emotional child who coins cutesy nicknames for other characters whenever he has the chance (“Flying Man”, “Evil Butterfly Man”). Just in case you missed the point, the writers actually regress Hiro’s brain to that of a 10-year-old for a while. But whether regressed or not, he and his pal Ando are treated throughout the series as the comic relief — goofy stunted Asians playing at being men.

To be fair, it’s not just minority characters in Heroes who are written poorly. White ethnics like the Irish are portrayed as tribal; the Italian Pettrellis are saddled with stereotypical crime connections and an unhealthy obsession with family. Mohindir has to endure a storyline where he becomes a mad scientist because nobody can figure out what else to do with a scientist besides making him mad. A big part of the problem with the show is simply that it’s crap. The scripts rely on stereotypes and clichés not out of any particular animus, but just because the people in charge are dumb and not especially creative.

Still, for comics folks, it can’t help but be a sobering spectacle. Heroes is embarrassingly bad in most ways. And yet, in its handling of minority characters, it’s significantly better than the vast majority of superhero comics. It’s hard to escape the conclusion that the mainstream needs to get much, much better before it can even be said to merely suck.