“Edward Said talks about Orientalism in very negative terms because it reflects the prejudices of the west towards the exotic east. But I was also having fun thinking of Orientalism as a genre like Cowboys and Indians is a genre – they’re not an accurate representation of the American west, they’re like a fairy tale genre.” – Craig Thompson, PopTones Interview, September 1, 2011

It’s easy to inventory my feelings about Craig Thompson’s Habibi. For well over a year, I approached its release with equal parts excitement and fear. The fear sprang from the 2010 Stumptown Comics Festival — held in Thompson’s hometown of Portland, OR near the completion of Habibi — as I sat in the audience of a Q&A session with him about the processes of publishing and creation. There he explained (as he has in many venues since) that Habibi was going to be an expansive book about Islam and the idea was birthed out a place of post-9/11 guilt he felt in reaction to America’s Islamophobic tendencies. Had he traveled much in the Middle East? No, except Morocco. Did he know Arabic? No, but he had learned the alphabet. At one point he actively said he was playing “fast and loose with culture” picking from here and there in order to tell his story as he saw fit. As I sat in the audience I saw red flags going up. I was about the spend a year abroad studying how The Adventures of Tintin is a Orientalist text precisely because Hergé rarely left the confines of Belgium while drawing the far off landscapes of India, Egypt, China, or made-up Arab lands like Khemed. And here was Craig Thompson some 80 odd years later, well intentioned, proposing a very similar project of creating a made-up Arab land of Wanatolia for the purposes of quelling his own guilt. What he called “fast and loose,” I called cultural appropriation.

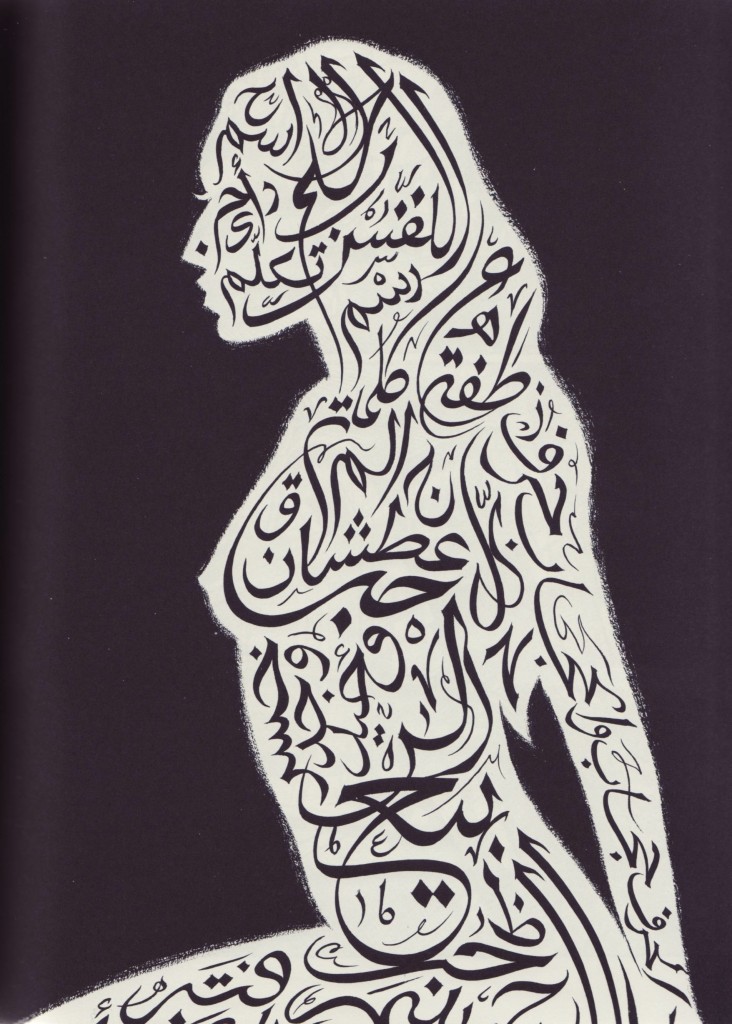

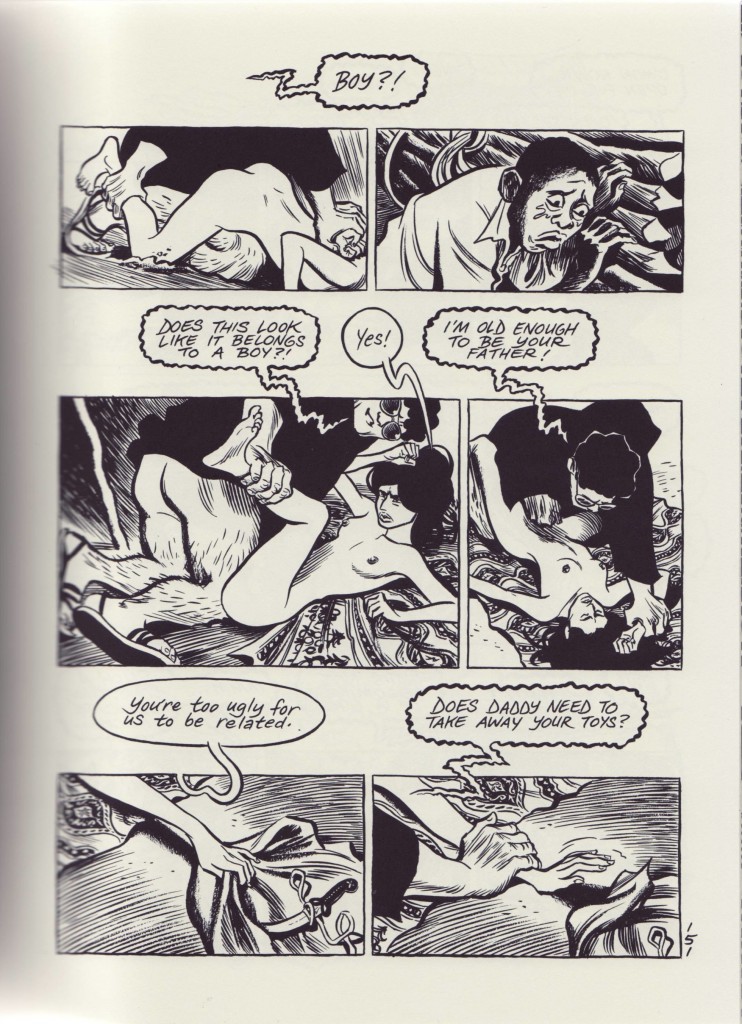

Habibi at its best and worst.

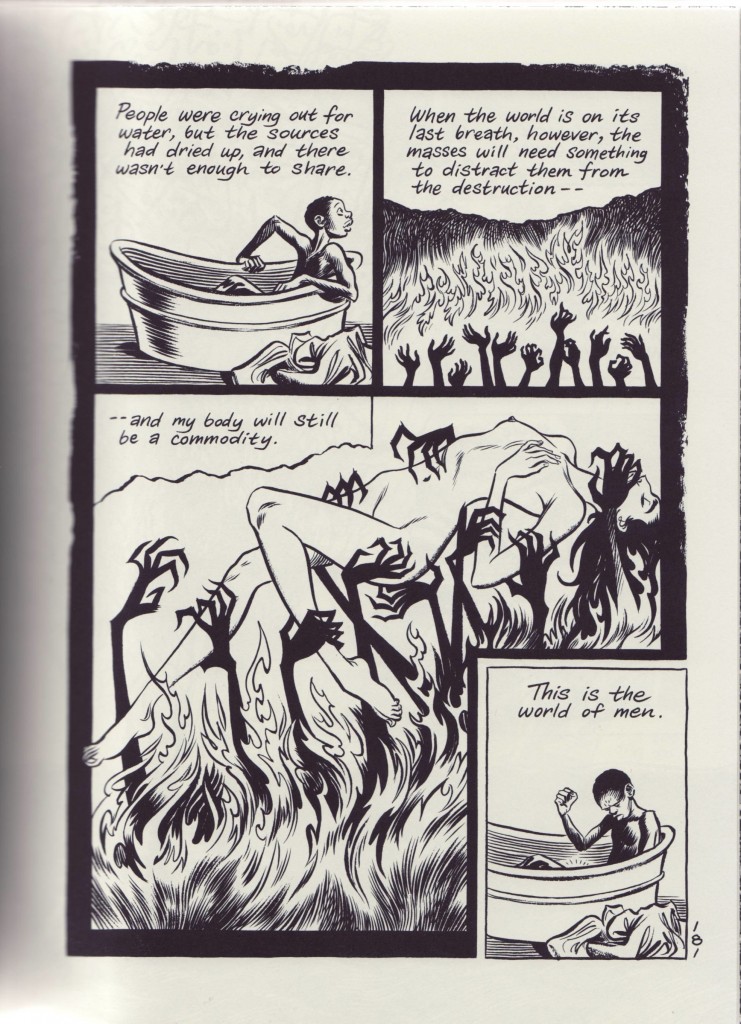

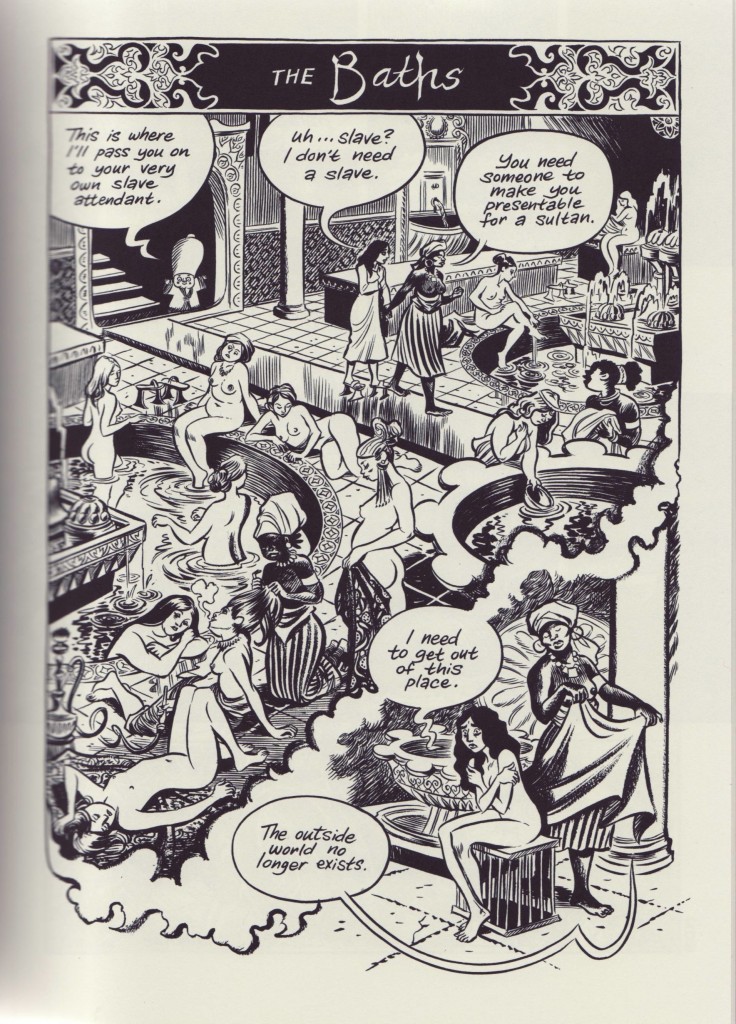

Now that the tome is here and I’ve had a chance to read it I feel no less nauseous or enthusiastic about the work that Thompson has produced. To be clear, Habibi is a success on many levels, but it also contains elements that are strikingly problematic through the lens of Orientalism. There are three key components to Habibi: Calligraphy and Islamic patterns, illustrated Suras from the Qur’an and Haddith, and a love story between the characters Dodola and Zam. On the first two counts, Thompson has more than excelled in creating a beautiful rarity for U.S. bookshelves. On the last count of the decades-spanning love story that Thompson has chosen to tell and the setting he has chosen to tell it in, I find that Habibi is a tragically familiar Orientalist tale that a reader can find in books by Kipling or many a French painter.

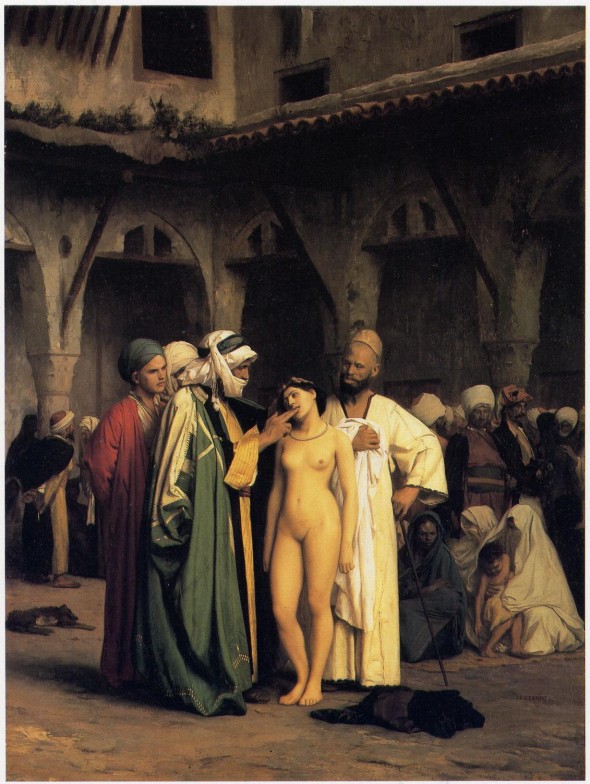

The Slave Market by Jean-Leon Gerome (1866)

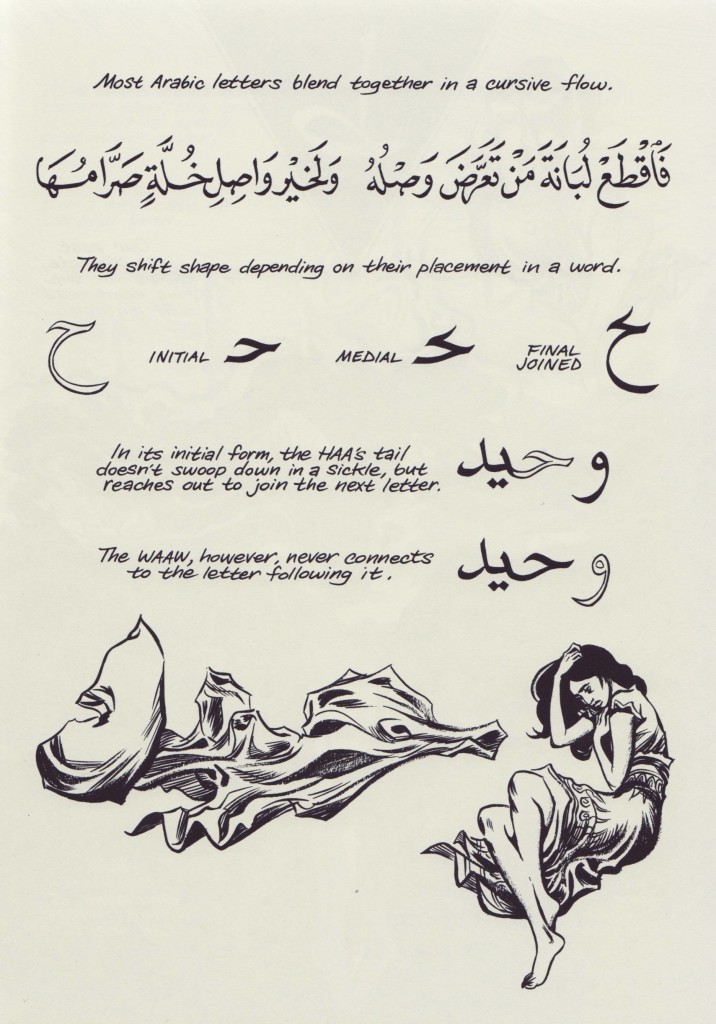

I will get to how the book fails to escape many classic Orientalist trappings soon, but first let’s discuss what Habibi gets right. The good is found foremost in the calligraphy and geometric patterns Thompson employs throughout Habibi. Given the technical skill and confidence Thompson uses when writing in Arabic, it is really unbelievable that he doesn’t actually know the language. Here is a prime example from early in the text:

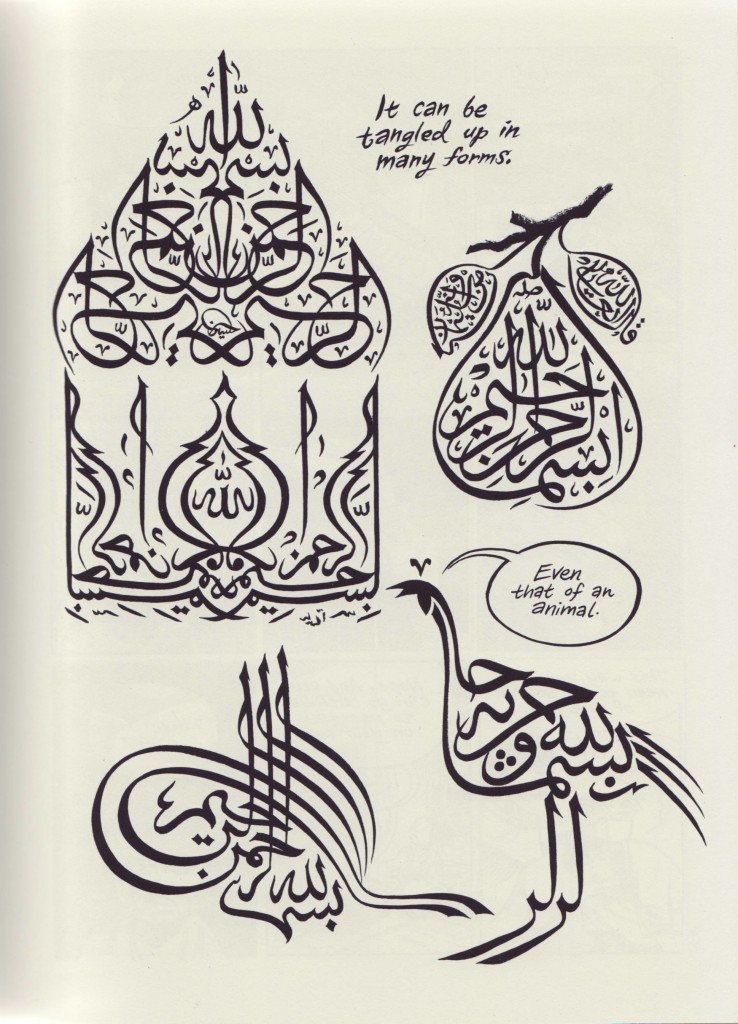

From any perspective this is stunning artwork. Through Dodola’s first husband, a scribe, Thompson creates a space to explore the beauty of calligraphy in the larger narrative. Therefore, on a meta-level, Habibi is a format for Thompson to practice calligraphy: an art form that lends itself well to the loose expressive brush line he made iconic in Blankets. As a reader, Thompson’s joy in learning the Arabic alphabet and how it can work simultaneously as a symbolic and literal art form comes across. His perspective as a non-native speaker with a strong artistic background works towards him making interesting connections about Arabic in Habibi:

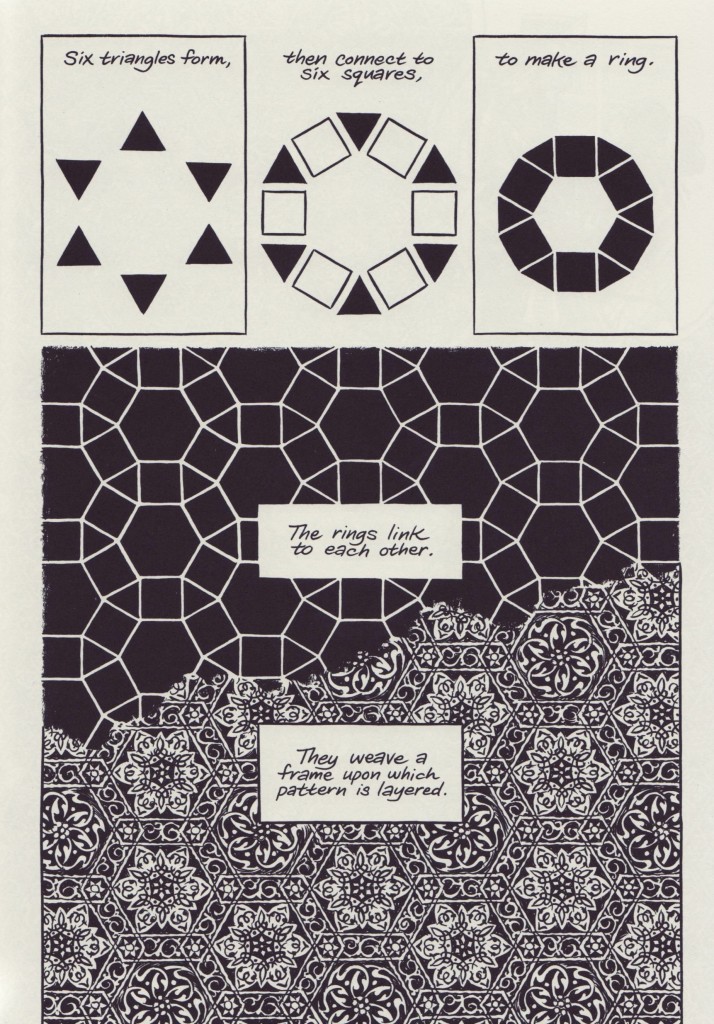

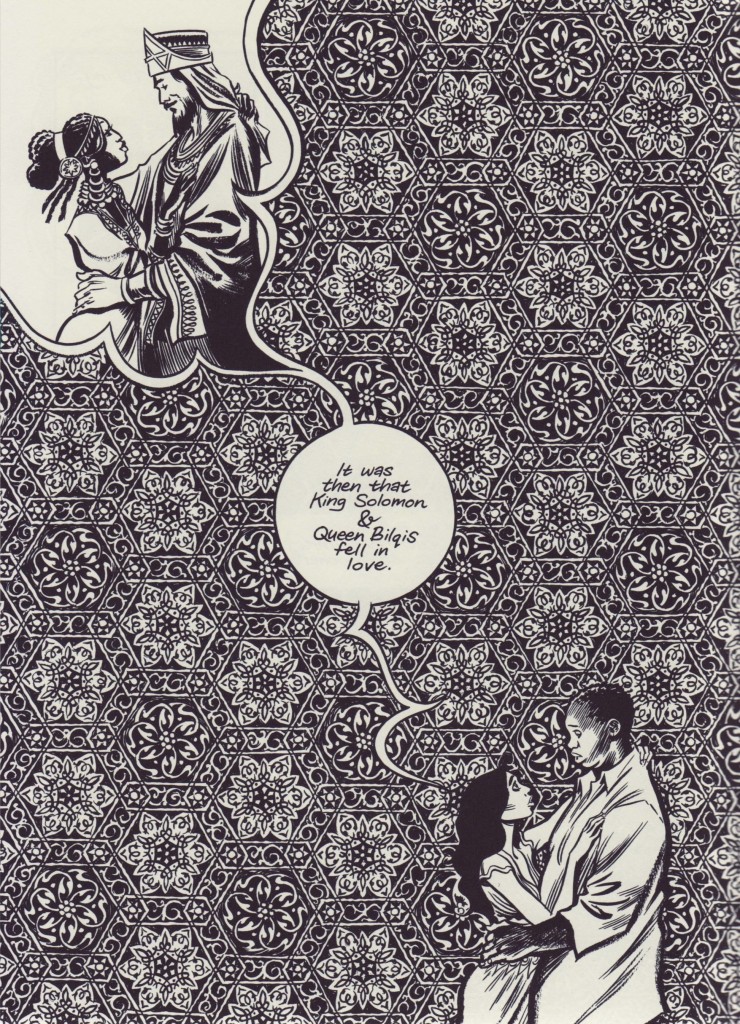

Along these lines, Thompson explores the geometric shapes of Islamic art to great success. The heavily detailed patterns he often uses in borders are the work of a talented, and slightly obsessive-compulsive, artist. The finely detailed explorations of Islamic patterns are a key part of what makes reading Habibi such a treat. As a reader I was often forced to pause in a page in praise of Thompson’s technical skill. While over-relying on this ornate style as shorthand for “Arab setting” made me raise a cautionary eyebrow beforehand, it is clear that Thompson is thoughtful in a way that escapes the pitfall. Here is a late in the text explanation of patterns that offers a glimpse into how thorough the cartoonist was in his research:

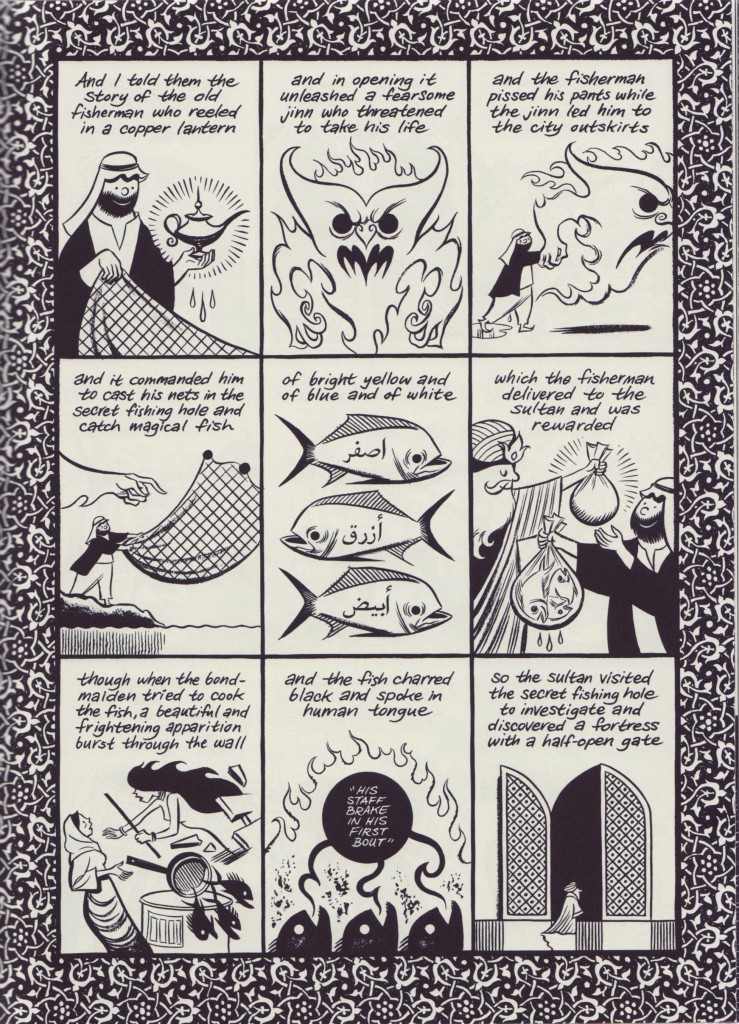

The second thematic triumph of Habibi is the manner which Thompson explores Islam. This clearly and heavily researched portion of the text contains the most exciting and memorable sections of Habibi by far. Thompson has mentioned the influence of Joe Sacco during the book making process and it is clear this is where Sacco’s research and report approach has influenced Thompson the most. Just as Sacco’s work lives in the footnotes of Gaza, here we get the product of Thompson diving deep into Islamic Hadith (the reported statements and actions of the Prophet Muhammad during his life), specific suras (chapters) of the Qur’an, and pre-Qur’anic mysticism. The threads he pulls out of his research are fascinating on their own right. His act of discovery is shared with the reader and it is clear he was excited to make it.

After reading the book it is evident that these are the sections Thompson refers to in his press when he talks about the book coming from a place of post-9/11 guilt. In the aftermath of September 11th, American Islamaphobia was predicated on understanding the attack by a few extremists as representative of an entire faith. Realizing this, Thompson uses Habibi to perform the due diligence of going into the Qur’an to reveal the large venn diagrams in between faiths. The question Thompson puts out there is: How can so many Christians and Jewish people be so against Islam when there are so many similarities between the faiths?

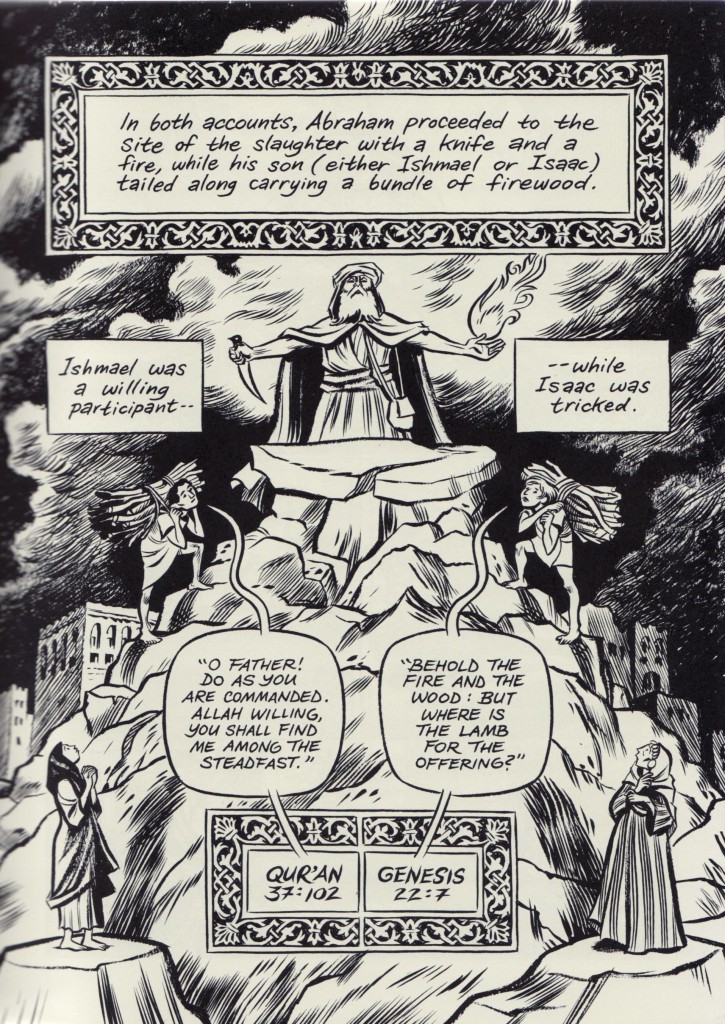

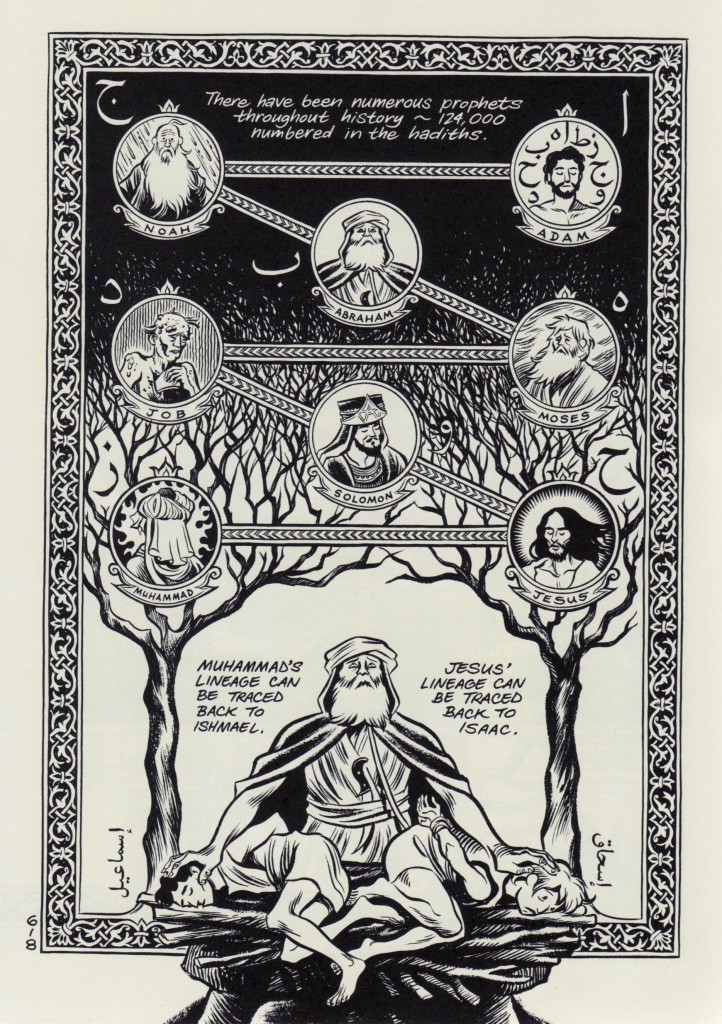

This exploration of the slight differences of the Abraham story between the Old Testament and the Qur’an — namely which son he takes to sacrifice — is one of the more successful uses of the Qur’an in Habibi. Thompson returns to this story of sacrifice multiple times in the narrative to increasing success, even when it simply used as a visual cue. By the end we get Thompson resolving the story by noting that in both versions what matters is that God spared the son, and from them the lineages of both faiths became deeply intertwined.

Thompson uses Habibi as a venue to argue that Islam and Christianity are not at odds with each other, but interconnected to one another. On this mark, Habibi is a well-done and original contribution to the canon of contemporary Western comics literature. I applaud Thompson for humanizing a religion that many have been quick to vilify, and for managing to do it in a non-preachy way. In fact, because he approaches Islam with a clear compassion and level-headedness, I suspect many readers let Thompson off the hook for the Orientalist elements of the text.

Which brings us to the bulk of the book: the love story between Dodola and Zam spanning multiple decades, set predominately in the land of Wanatolia. While this story is drawn with the same detail-attentive pen that Thompson uses at the service of calligraphy and geometric patterns, here it predominantly captures the vagueness of stereotypes. Thompson contributes to (instead of resisting) Orientalist discourse by overly sexualizing women, littering the text with an abundance of savage Arabs, and dually constructing the city of Wanatolia as modern and timeless.

One of the biggest missteps that Habibi makes is relying heavily on unrequited sex as a main narrative thrust. In John Acocella’s critique of Stieg Larsson’s popular Girl With The Dragon Tattoo series from earlier this year, he notes that some charge Larsson of “having his feminism and eating it too” based on the blunt manner in which he uses rape as a plot device. I think a similar charge can be laid against Thompson, who uses the repeated rape (and sometimes consensual sex by circumstance) of Dodola as an emotional tool that never feels wholly earned.

The rape of Dodola

What Thompson makes repeatedly explicit throughout Habibi is implicit in the classic Orientalist painting “The Slave Market” by Jean-Leon Gerome pictured earlier. In that painting, as with many more from the same era, the savagery of Orientals is imagined by European artists and portrayed for European audiences. What is reflected in these paintings is the White Man’s Burden: the felt need among those in the West to save Arab women from Arab men. By imitating the style of French Orientalist paintings as a vessel for his story, Thompson also transfers the message those paintings are loaded with. It is the same White Man’s Burden that drives readers to register Dodola as a damsel in distress (a position she inhabits for the majority of the book). She needs saving from the savage Arab men that over-populate the book.

Furthermore, Thompson creates a world where Dodola’s chief asset is her sexed body. She sacrifices herself to men to feed Zam, gain a version of “freedom” with the Sultan, and save herself from jail. Thompson crafts a societal position for the main character of the book where she must always be exotic and sexualized. Proof of our empowered heroin:

The thing about this version of empowerment (as Acocella argues with The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo) is that while readers do feel solidarity with Dodola, they are also given a space to live out a version of their own sexual fantasies via the text. It’s hard to make the distinction between a character being overly sexualized as a necessity for a larger feminist narrative and the reality that the product of this narrative is a book with a nude exotic Arab woman in panel after panel.

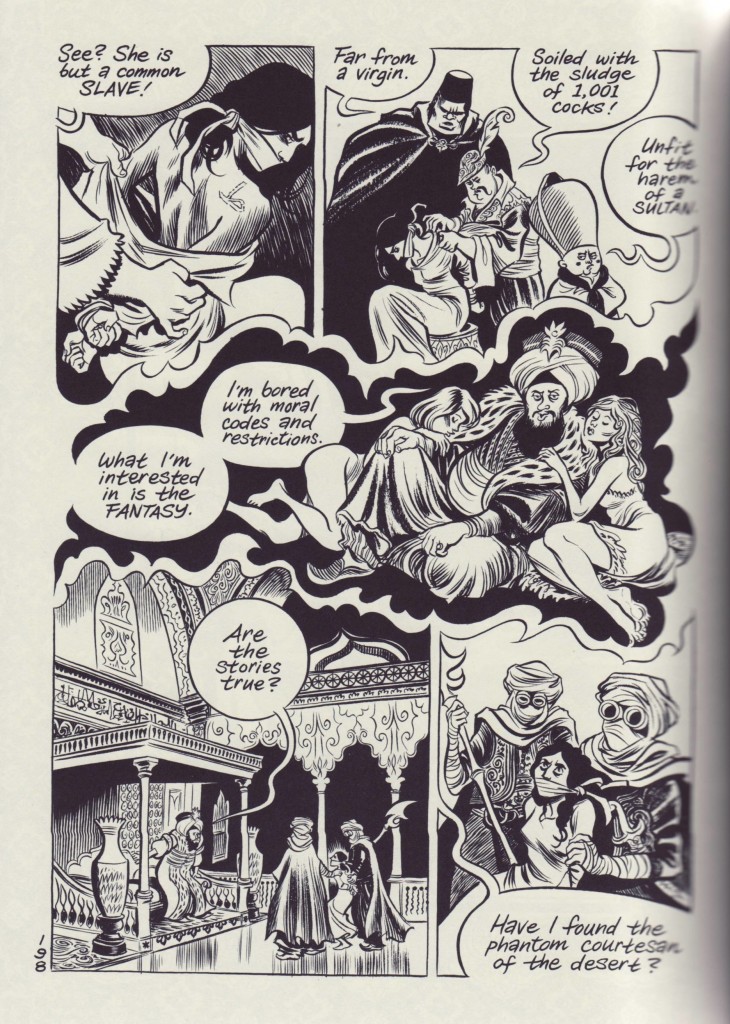

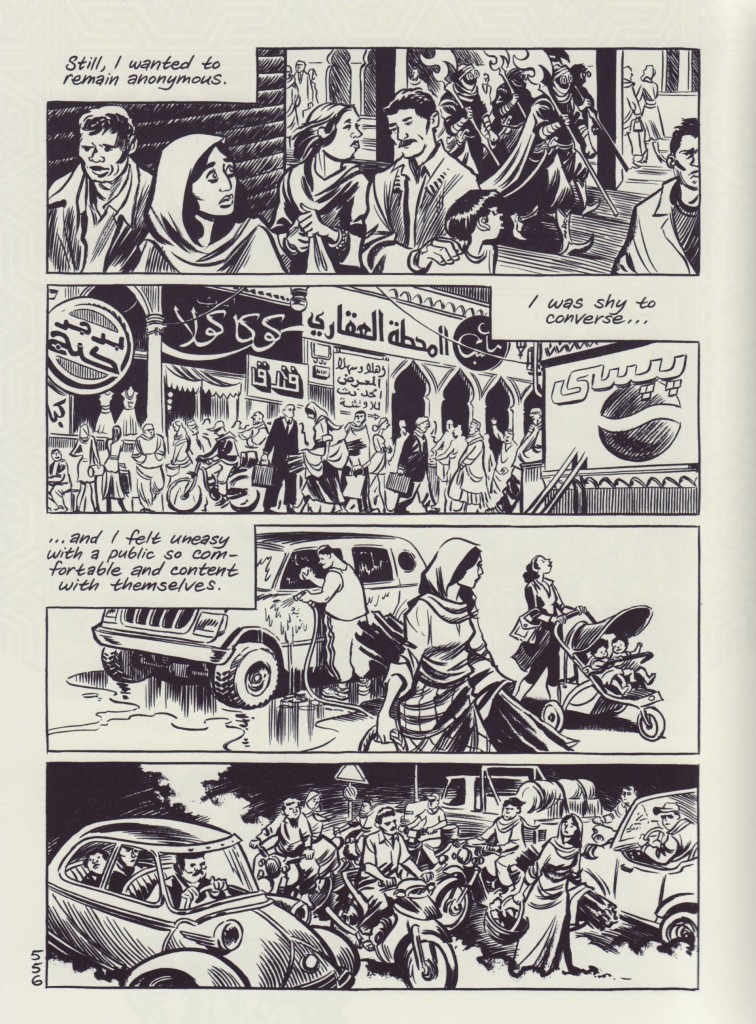

The question, then, is if Thompson so badly wanted to tell a story about what sex means in the context of love (familial to sexual), survival, and sacrifice, why did he choose this vessel? The answer I come to is that because this was the easy context. The artistic playground he chose of barbaric Arabs devoid of history but not savagery is a well-trod environment in Western literature, and one that is consistently reinforced in the pages of Habibi. In too many panels, Thompson conjures up familiar and lazy stereotypes of Arabs. From the greedy Sultan in his palace, to the Opium dazed harem, to the overly crowded streets of beggars, and the general status of women as property, Thompson layers the book with the hollow caricatures from other literature. These settings are easy to imagine because they have been passed down and recycled throughout much of Western media, so we immediately register these vague settings as natural:

Nudity in Sultan’s Harem

Thompson constructs a version of the Orient that is filled with savage Arab men and sexualized Arab women, all at the service of penning a humanizing love story between slaves. The thing about humanizing, the way that Thompson does it here, is that while Dodola and Zam arrive as three-dimensional characters, they are made so by comparison to a cast of extremely dehumanized Arabs. While reading Habibi you can count the characters of depth on one hand with fingers to spare, but the amount of shallow stereotypes embodied in the supporting cast is staggering. The Sultan’s palace perhaps contains the most abundant examples of Thompson’s Orientalism. For the majority of the comic that takes place in the palace, the dialogue is so cliché-ridden that one could take out the words from the panels and the flow of the story would not be disrupted.

The Tusken Raiders present “the phantom courtesan of the desert”

Thompson has often mentioned the influence of 1001 Arabian Nights on him when creating the setting for Habibi. It’s easy to see this connection through Dodola’s status in the palace, but I think Thompson may be understating the influence of a more contemporary take on one of those tales: Disney’s Aladdin. In the same way that this Gulf War children’s classic is a prime contemporary example of Orientalism in America, Habibi repeats many of the moves in a more highbrow setting. As Aladdin opens, a nameless desert merchant sets the tone for viewers in a song about the Arabian Nights we are entering:

Oh I come from a land, from a faraway place

Where the caravan camels roam

Where they cut off your ear

If they don’t like your face

It’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home*

I thought of these lyrics repeatedly while reading through Habibi, as I could easily imagine the same desert merchant popping up in panels of Habibi to chime in: “It’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home!” In Habibi, Dodola and Zam are struggling for a better life in a fixed system of backwardness. What is ultimately most frustrating about the brutality of Habibi‘s Arabs is it is a brutality that is never justified or made to face consequences: it just sits there as normalcy. Dodola being raped, the harsh way the city treats Zam when he is on his own, the Sultan’s ruthlessness, the caravan camels roaming: these are all just acceptable facets of Wanatolia being a faraway place. Like Arguba in Aladdin, Wanatolia is a made-up and timeless setting for love to spring in spite of Arabness.

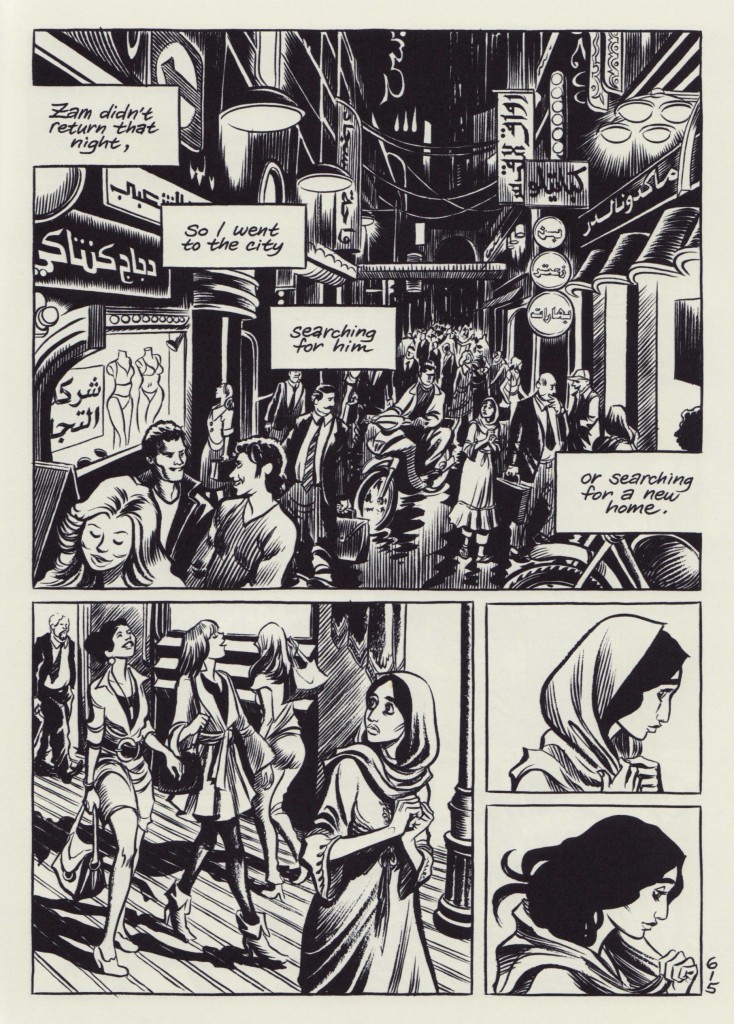

Wanatolia represents the heart of Habibi’s most problematic elements. In the sense that Habibi is a fairy tale (which Thompson has stated he was intending to create) it is understandable that the city is constructed as “timeless.” In other words, the majority of Dodola and Zam’s story isn’t tied to an analogous timeline. The problem arises when in the latter chapters of the book Thompson reveals that the same backward setting of Wanatolia (which houses the harem filled palace of the Sultan) dually houses a modern urban city. When Dodola and Zam return to Wanatolia after escaping the palace and recouping with a fisherman, we see the city in a completely new light: it is now a vibrant bustling city with billboards for Coca-Cola and Pepsi, SUVs, and free women pushing strollers.

The reveal means that readers now have to reconcile that the same city of Wanatolia houses in a small proximity a site of forced sexual slavery and a site of Western-style modernity; a city where an Arguba-like brutality lives in tandem with a KFC. Therefore, Thompson presents a version of modernization for Arabs that is fueled by backwardness. The entire events of the book are retroactively a modern reality in the wake of an urban Wanatolia.

Dodola flirts with “being modern,” where “being modern” means taking off the hijab.

Wanatolia represents the poignant identity crisis at the heart of Habibi: it wants to be a fairytale and commentary on capitalism at the same time. The problem is that in sampling both genres so fluidly, Thompson breaks down the boundaries that keep the Oriental elements in the realm of make-believe. In other words, the way in which Wanatolia is portrayed as simultaneously savage and “modern” reinforces how readers conceive of the whole of the Middle East. Although Thompson is coming from a very different place, he is presenting the same logic here that stifles discourse in the United States on issues like the right to Palestinian statehood. If we are able to understand Arabs in a perpetual version of Arabian Nights, then we are able to deny them a seat at the table of “civilized discourse.”

Ultimately, when looking at Habibi we are left with the value of intention. Thompson has argued rather convincingly in recent talks that the book is knowingly Orientalist and he wanted to engage with these stereotypes to simply play within the genre. As he claims in the quote that leads this review, he intended to use Orientalism as a genre to tell a tale about Arabs the same way that stories in the genre of Cowboys and Indians are both fun and inaccurate. The problem in making something knowingly racist is that the final product can still be read as racist.

I know that Craig Thompson is a great guy who would probably win an award for thoughtfulness if such an award existed, but the issue remains that Habibi reproduces many of the Orientalist stereotypes already abundant in Western literature and popular culture. Although Thompson set out to play with these stereotypes, he never does a good enough job distinguishing what separates play from his own belief.

Habibi is an imperfect attempt to humanize Arabs for an American audience. There are definitely large technical and thematic triumphs to note, some of which I’ve mentioned here (from calligraphy to Qur’an) and others of which I didn’t get to (particularly the role of water/environmental concerns in the narrative). On an aesthetic level, Habibi is a wonderful experience that I recommend to anyone with spare time and the ability to lift heavy objects. Thompson is one of the most talented comic artists and writers working today, and that he took seven years working on Habibi is evident in the ink on display throughout the book. Yet, between the eroticized women, the savage men, and the presentation of these elements as constituents of Arab modernity, it is unfortunate Thompson’s skills are being used at the service of a mostly Orientalist narrative.

* The lyric “they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face” was removed in subsequent versions of Aladdin due to a complaint by the Arab-American Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC). I recommend reading the ADC’s explanation of the situation.

_____________

Update by Noah: Nadim’s thoughts have inspired an impromptu roundtable on Orientalism. which can be read here as it develops.

The images above remind me of Will Eisner. That, coming from me, is far from a compliment…

Eisner seems like a good comparison, both in the skill of the craftsmanship and in the problematic content.

Nadim, I wonder what you think about Neil Gaiman’s forays into Arabic settings in Sandman? I think he was more on top of the Orientalism than Thompson seems to be, but it seems like you might still find some of the same problems in his work….

This is exactly why, despite how much I’ve enjoyed Thompson’s other work, I have very little desire to read Habibi. Everything I’ve read about his approach to the work as well as the excerpts I’ve seen make me deeply uncomfortable and Nadim’s excellent article only confirms those sinking suspicions.

Excellent and to the point, Nadeem. And as you I find it hard to believe the guy cannot read Arabic with such calligraphy.

As to the points you made, I’ve found it very difficult to found a novel about Arabs that I can relate to. Any suggestions?

*find

Over-eager auto correct!

Domingos and Noah, that Eisner comparison is really apt and I didn’t see it before.

Noah, the Sandman stuff is an interesting thread to pick up on. At last reading I think I gave Gaiman more of a break in general because it is so explicitly fairy tale, but now I want to return to it to see how he handles Oriental tropes. There is definitely a way to do this stuff right, but I think it comes foremost with acknowledging the author’s subject position in the text (precisely why I think Sacco is such a great example because he literally inserts a version of himself in the narrative).

Andrew, thanks so much for the kind comment. You might want to give it a look for yourself, because there are some emotionally poignant parts intermixed with these problematic elements. Like I say in the article, I really like the Qur’an work and calligraphy, in addition to a few more stand alone stories like one of this fisherman. But yes, you are right (and commended!) for feeling uncomfortable.

Abdullah, thanks for the comment! I’ll shamelessly point you to my last column where I catalogued the contemporary Arab comics in the Middle East: https://hoodedutilitarian.com/2011/09/can-the-subaltern-draw-a-survey-of-contemporary-arab-comics/. I feel there are some really strong titles in there, so the future of better representation might just be the Internet.

I think I’m thinking of the story P. Craig Russell illustrated specifically? There’s some other bits too scattered throughout….I was going to say that I don’t think Gaiman sexualizes the women quite as adamantly, but now I’m not so sure…

I think Caroline Bren a bit back was talking in comments about how the Islamic treatment of women is often used as an excuse/occasion for imperialism. That painting you have is a particularly painful example. It’s condemning the Arabs for mistreating women while using their mistreatment as an excuse for prurient display (given piquancy by the fantasy of Westerners as noble rescuers, I think.) Juxtaposing it with Thompson’s Muslim-woman-throws-off-the-veil moment is a righteous takedown.

I really hope that veil page makes more sense in context, because on its own it comes off incredibly poorly. I guess it’s the prospect of such blatant missteps that, redeeming qualities aside, makes me hesitate to read Habibi — I imagine they would color my enjoyment of other Thompson works, as misguided as that might be.

Nadim, in the discussion you heard at Stumptown, did Thompson talk at all about his research for the narrative, beyond the calligraphy and art and I presume the Koran? Did he read any postcolonial fiction or theory? It sounds like maybe he read Said (perhaps cursorily?) but what about Bhabha or Spivak, or fiction writers like Mahfouz or Khoury? Do we know anything about the influences on the story he told?

Thompson’s statement is really confused:

“Edward Said talks about Orientalism in very negative terms because it reflects the prejudices of the west towards the exotic east. But I was also having fun thinking of Orientalism as a genre like Cowboys and Indians is a genre – they’re not an accurate representation of the American west, they’re like a fairy tale genre.”

I think Thompson’s trying to say that by treating Orientalism as a genre he’s taking the wind out of its sails by revealing its status as a fiction. The problem is that genre fiction has been an important vehicle for Orientalism, just as its been for the “Cowboys and Indians” fiction, and the nasty stereotypes and jingoist mythologies it perpetuated. Of course, you can subvert the genre to reveal its contradictions, and even have some fun doing it… Jarmusch did both with “Dead Man” and the western. But if you just have fun with Orientalism, then all you’re prety much doomed to perpetuate it.

Actually, there’s a name for “thinking of Orientalism as a genre like Cowboys and Indians.” It’s “exoticism.” It’s one of the things that post-colonialism eviscerates.

I’m sort of fond of exoticism, actually; I think it’s vastly less dangerous than jingoism. If you can get someone interested in a narcisstic notion of the Other, you have a much better chance at nuancing that notion into something mature than if the person just hates all Others to begin with.

But I do see the post-Colonial point — if it never matures, it’s dehumanizing. I haven’t read Habibi yet, but it’s sad if it’s uncritically orientalist. That’s why I’m curious about his influences on the story, if any actual Arab voices got any say in the research.

Nate, you articulate the point perfectly. That is exactly what I was going for in my critique of how Thompson uses Orientalism.

Caro, I actually conducted a follow up interview with Thompson where I took the opportunity to press some of these questions on him. I really do believe he was thoughtful in the research process. That said, I don’t thing he read much or any Said, Spivak, Bhabha, etc. As to broader influences he read a lot more Sufi and mystic stuff in his research. As I state in the review, he cites 1001 Nights as a major inspiration for Habibi, but even from his first reading of that felt it was a problematic. Also, he stressed that he always ran stuff by his Muslim friends when he thought he was crossing a line. I think he was really trying to play savvily with Orientalist tropes, but under-calculated the weight of the imagery he was using. Again, I think he had good intentions but because of the lack of distinctions he draws it is a poor execution.

“but under-calculated the weight of the imagery he was using.”

In part it seems like he really wanted to draw lots of pictures of nude girls. Not a horrible impulse in itself, but perhaps didn’t dovetail with his other goals as he hoped it would….

Caro,

I agree that exoticism could yield art that encourages readers to investigate further, but it’s still a risky rhetorical move compared to genre subversion, which is itself already pretty risky (particularly when irony is involved; irony is a slippery trope, and demands a lot of faith in audience).

Noah,

I agree, CT’s desire to draw attractive women(by mainstream contemporary western standards) makes the characters look all the more like a fantasy projected onto the other. But what I’m more in is that in the pictures I’ve seen so far, he avoids drawing vaginas. Why demure on this aspect of his chosen subject’s anatomy?

“Why demure on this aspect of his chosen subject’s anatomy?”

So you can sell it in family bookstores? There’s lots of commercial reasons to stick to the R rating…

Pingback: Comics A.M. | Digital comics milestone; Kickstarter’s patent battle | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

Actually, Thompson does draw cross sections of vaginas at various points in the book. What he doesn’t draw are labia. I don’t think I saw a penis either but I could be mistaken. The external genitalia of men and women was the last thing on my mind when I was reading this book.

I love reading your column because it always makes me PANIC about my own writing, and whether or not I’m appropriating exotic cultures to mix and match in my own convenient fantasy scenario. Very fair, very thorough. Makes me think.

There’s an old joke that the difference between art and porn is public hair. I think the commercial explanation makes sense, though that’s complicated by Ng Suat Tong’s comment, though I’m not sure what he means by cross section.

Pingback: Gaze in wonder at Brandon Graham’s Habibi fanart | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

Pingback: Read Comics!: Your Comic Book News Update « Philmalot!

Interesting dissection. Beautiful pages but troubling imagery. While there’s something to be said for the fictionalization of cultures by outsiders, I think problems begin when fictionalization crosses the line into trivialization.

Do these images remind you of a specific Eisner book?

AJA: I don’t know if the comparison harkens to a specific example, but they do share a certain gnarly angularity, and the devil’s touch of modeling their blacks as if slopping them on from a great distance, yet with practiced precision.

The comparison between Eisner’s bizarre lapse into spit-take inducing racist caricature and the issues at hand might be coincidentally apt. I’d like to hear the comparison dug into at greater length.

They look more like late Eisner (Contract with God and after)—There are some similarities with his exotic women from The Spirit too, though. “Sand Sarif” and “P’Gell”—the first splash page for a P’Gell story takes place in the East, if I’m not mistaken, and it has some similarity to these. The first thing I thought when I saw these images was “Eisner”– but, of course, somebody had already said it.

I feel like Thompson’s talked about an Eisner influence…did I imagine that?

These pages share late Eisner’s awful melodramatics.

Noah, you maybe imagined him specifically citing Eisner. For awhile now, Thompson has been quick to list French artists like Blutch and Lewis Tronheim as the predominate influences on his style.

Tom Spurgeon and Sean T. Collins draw at the Eisner/Thompson connection a little more in this 2010 reflection of Blankets: http://www.comicsreporter.com/index.php/resources/interviews/26619/

Eisner is clearly a major influence, not just formally but also in terms of sensibility. As is Blutch. But Thompson generally wears his influences on his sleeve.

Great piece. Telling the story you want to tell while also being respectful and mindful of EVERYTHING just seems so difficult. The stain of colonialism feels almost inescapable sometimes. Telling a story set in a different culture/time is fun, but so very difficult to do right if you have little personal experience with that culture.

To think 7 years of research and an honest attempt to be thoughtful and fair was still not enough. Well, I guess art/writing isn’t for the lazy anyway!

In Carnet de Voyage, Thompson lists great urban cartoonists and Eisner is one.

Guernica: When you say you decided to embrace Orientalism, what do you mean? Orientalism, after all, is a form of racism that sees people in the Middle East and Asia as different or magical or … not modern or rational. (Amartya Sen wrote for us about how in Western writings Indian author Rabindranath Tagore is reduced to his ‘spiritual’ views rather than his rational ideas.) How did you hope to navigate this?

Craig Thompson: “Embrace” may not be the right choice of words. The book is borrowing self-consciously Orientalist tropes from French Orientalist paintings and the Arabian Nights. I’m aware of their sensationalism and exploitation, but wanted to juxtapose the influence of Islamic arts with this fantastical Western take. This is a constant theme in the book of juxtaposing the sacred and profane. As for the latter concern, I didn’t consider it much as I personally ascribe to a sort of “magical” worldview rather than rational. The book is concerned with the connectivity of everything.

from here: http://www.guernicamag.com/interviews/3073/thompson_interview_9_15_11/

————————

Abdullah Damluji says:

Excellent and to the point, Nadeem…

————————

Yes, a very thoughtful and fair-minded critique.

————————

And as you I find it hard to believe the guy cannot read Arabic with such calligraphy.

————————

Tch! Could there be a more unintentionally revealing example of Thompson capturing the form, while failing to understand the meaning, much less essence?

————————–

Guernica: …Orientalism, after all, is a form of racism that sees people in the Middle East and Asia as different or magical or … not modern or rational. (Amartya Sen wrote for us about how in Western writings Indian author Rabindranath Tagore is reduced to his ‘spiritual’ views rather than his rational ideas.)…

—————————

Fair enough. Yet, Orientalism is simply another of the countless simplified, distorted versions we have of other groups, historic periods and events; which serve ideological, psychological, or political functions. (For instance, in contrast to the Old West of fiction, divided between white cowboys and Indians — with a greasy Mexican tossed in for variety — in actuality, from one-third to 3/5ths of cowboys were black: http://ramblingbob.wordpress.com/2008/06/27/more-on-black-cowboys/ .) Let’s not make it seem like those awful white colonialists had the market cornered in seeing the Other in a self-servingly warped fashion. Did not old China and Japan consider the rest of the world to be “barbarians”?

Someone ought to write an “Occidentalism” book; about how, to non-Westerners, an image of this realm exists as stereotyped and caricatured as its counterpart, propagated worldwide by our mass media. A land of universal wealth, freedom, equality and comfort; the epitome in civilization*, style and advancement, to be emulated at all costs (i.e., China rushing to embrace wide use of the automobile and building expressways), even as its shortcomings and the disasters its ways lead to become all too undeniably evident.

Even if Thompson’s use of “so-called” in the Guernica interview…

——————————

Craig Thompson: I think anywhere in the so-called “developing countries” there’s this boundary where the old and new brush up against each other…

——————————

…indicates awareness that the propagandistic term “developing” pushes an attitude that if a society isn’t Westernized and industrialized, it ought to be moving in that direction, the excerpt showing Wanatolia as “a vibrant bustling city with billboards for Coca-Cola and Pepsi, SUVs, and free women pushing strollers” gives the idea Thompson has a similar attitude; Westernization = civilization, freedom, enlightenment…

BTW, has anyone here seen the abysmal “Veils”? ( http://www.amazon.com/Veils-Pat-McGreal/dp/1563895617 ) I bought it ‘way back when ’cause I was interested in its use of Photoshop to create manipulated imagery for a graphic novel; but the story… (groan)

*Or universal immorality and decadence, if you’re an Islamist fundie…

Hey Nadim-

Have you read the new David B. book, The Armed Garden? One of the three stories in that volume is the story “The Veiled Prophet” which was originally run in English in Mome. I would love to hear your thoughts on it in relation to Habibi and Orientalism. David B. too is playing with very familiar Orientalist tropes but in a way which I thought was much more successful. He has apparently also now published in French a comic or an illustrated book, not sure which, about the “West” and “Islam” and their historical relations.

Ethan, I haven’t read The Armed Garden, but I am a fan of David B. so it sounds definitely worth at least tracking down that issue of Mome. I’ll let you know my thoughts when I check it out. Thanks for the recommendation!

I wonder if there’s any fruit to comparing the Sultan’s portrayal to some sort of Western fiction with an “Evil CEO” of a large, polluting corporation who also slaps around his hottie mistress while verbally abusing his complaining wife. No doubt, it’s a staple of so many stories these days (always?) to reduce an antagonist to a short list of loathsome characteristics, but how many of us liberal types who bother thinking about such things blink twice when we read a Western straw man whose position in life we generally aren’t too fond of in the first place? I’m not sure the “Evil Sultan” is any more or less culpable than the evil priest, evil terrorist, evil politician (left or right), evil cop, evil low-level criminal or evil drug kingpin. Is it really a matter of history alone, or is it where we naturally put our sympathies – high or low?

Knowing next to nothing about the true lives of powerful Arabs, I wonder whether Arab writers treat such figures fairly, or if they also show their higher castes (royalty) leering, preening and murdering without conscience or reflection. I would think the executive who rationalizes the destruction of the dam in the last third of story is probably closer to reality.

I suppose better writing would give me insight rather than genre tropes and types. I don’t generally go for stories that portray evil anything. I’m too old for fairy tales.

I don’t think evil’s a fairy tale; people do evil things, certainly.

The problem with most portrayals of corporate villainy is that, (a) it’s generally presented as aberrant — the bad guy is a bad apple rather than part of systemic corruption; and (b) the bad guy usually loses, which, alas, in real life is a rarity.

Evil acts aren’t a fairy tale. Evil people are.

I disagree with the reviewer’s focus on Orientalism. I can see criticizing the book for being cliché ridden or having shallow characters, but putting the Orientalist label on it implies that the Arab world is a politically correct subject that has to be approached only in a certain way.

This is really just a form of censorship. Thank God (or Allah) that Thompson didn’t have the same misgivings.

BTW I wasn’t going to buy his book, but after seeing the drawings I definitely will. They are stunning.

Allen and JDL-

The problem is deeper than just a stereotype or a cliche. Yes, rich white man can be turned into evil stereotypes too, but the difference is that rich white men are not the objects of imperial power. “Orientalism” the book is about demonstrating how the racist popular imagination of the Middle East (and other brown parts of the globe) directly informs and enables the ongoing colonization and subjugation (whether direct or indirect) of those people. The problem, it sounds like, is that Thompson is perpetuating those same myths. They do not exist in a vacuum, and even if Thompson has the best of intentions, they fundamentally perpetuate the same power dynamics. I believe that Thompson the artist has a right to what he pleases, but Thompson the human being has an ethical choice to make when engaging with racism.

JDL, I think you’re confused about how censorship works. If a government disallows Thompson from publishing his work, that’s censorship. If someone like Nadim writes on a blog that he believes Thompson’s representation of Arab people is cliched and perpetuates harmful stereotypes, that’s free speech.

The inability to tell the difference between an expression of opinion and government censorship is endemic, and has done a real disservice to our public conversation, IMO.

To further that conversation…would you feel that Nadim was being politically correct if he criticized someone for using blackface caricature? For denying the Holocaust? For promoting Communist ideology? For advocating the rape of white women (as Eldridge Cleaver did?) I presume that there’s something Thompson could have done in his graphic novel that would have led you to say, gee, that’s kind of offensive, I don’t agree with that. As long as that’s the case, the issue isn’t political correctness or lack thereof, but rather what your own politics are, what you find objectionable and what you don’t. If you don’t find Thompson’s representations of Arabs objectionable, explain why. But don’t pretend that artists get a free pass to say whatever they want and that nobody should ever criticize them for it. Thompson isn’t a priest or a god, and nobody is obligated to take his words as gospel.

“If you don’t find Thompson’s representations of Arabs objectionable, explain why.”

Why should I be required to explain anything? Both you and Ethan are using race to decide what is and is not an acceptable subject. Other comics are filled with less than desirable characters, so why the special treatment here?

I didn’t see anyone leap to the defense of Christians in Blankets. I suppose you think that’s because (mostly white) Christians are “the objects of imperial power.” So it’s A-OK to have at them?

I feel that all cultures should be given the same respect – or lack thereof. Your approach appears to be to first check the race of the subject, and then proceed accordingly. That sounds pretty racist to me.

If you honestly want to respect other cultures, you should treat them as you would you own – which can be a wide spectrum of humor, criticism, flights of fancy, etc. It’s really a shame that people seek to restrict what can be said about other cultures.

As I read the book, Eisner similarities occurred to me more readily in relation to the use of page-as-panel, the line weights, shading and what Eisner liked to call “expressive anatomy”, rather than story, characterisation or attitude. Actually, AJA, the artwork reminded me most of Life on Another Planet, which makes it sound less accomplished than it is.

There are dangers about being too broad brush about “Orientalism”, and I think that condemning any work set in a country the author has not visited (especially the imaginary ones), as Nadim does with Hergé, is to go too far. But Habibi is quite relentless about applying the tropes of orientalist fictions in a way that draws attention to itself. Thompson’s defence that he is operating within genre would work better if there were some sign of him playing with those tropes or challenging them (in the manner of revisionist westerns), rather than merely repeating them.

I didn’t find the mix of medieval and modern as jarring as Nadim did, partly because I spotted the motorcycle at the start, but also because the Aswan damn and the Kuwaiti/Saudi/Bahrainian narrative of privileged opulence built on the exploitation of the excluded, particularly foreign workers, seems to me to be as much a part of western ideas of the Middle East as the sybaritic harem. If only it was as untrue.

JDL – I don’t think that anyone is “seek[ing] to restrict what can be said about other cultures.” Rather, we are discussing what is being said.

For that matter, Noah, I’m not sure that I find Thompson’s representations of Arabs so much “objectionable” as depresssingly stereotypical, in a book which is supposed, in part, to be a celebration of storytelling.

Habibi is a major work of art, and major works of art attract this kind of small-minded punditry like stallions attract horseflies. It is not above criticism, but it is above this criticism.

I have a character in a project I’m working on who comes out of a background in postmodern/postcolonial studies, and if I had her write the above review, I would be accused of stereotyping academics. The author drops a pomo coinage into the title, throws the work down on the same rack upon which the works of Kipling and Gerome have already been thoroughly tortured, and in the most conformist manner possible, concludes that the author is trafficking in racism and sexism. And after a protracted public display of grief that Habibi has inflicted a literary and artistic wrong upon Arabs (conceived, of course, as the victims of colonialism, not as some of its most enthusiastic practitioners), the first commenter comes out and insults a Jew. No one notices the irony. I see some people who are tone-deaf to the implications of what they are saying, but Craig Thompson isn’t one of them.

It would be nice to see someone besides Caro demonstrate that you can study Theory and its related enterprises without it destroying your self-awareness and critical faculties, and replacing them with prefabricated opinions. Needless to say, I disagree with many of Damlugi’s conclusions about Habibi, but why argue about them? I doubt he could have reached different ones if he tried.

His name is Nadim Damluji, Franklin.

And he says he loves the art. He praises Thompson repeatedly. He calls him one of the more thoughtful creators he’s read. Your contemptuous dismissal, and refusal to discuss the work with someone who hasn’t even condemned the thing, says more about your preconceptions than his, alas.

I’m sorry for misspelling his name.

Also…I am going to try to remain calm about this, but as a Jew, I find your resort to vague accusations of anti-Semitism absolutely repulsive. To suggest that Eisner is less than a god is not to make any comment about his Jewishness. Your assertion would be ridiculous if similar things were not said so often in our public discourse, and with such harmful effect.

In general I find your comments valuable and I am always grateful for your perspective. I disagree with the rest of what you have to say, but I certainly think it’s a reasonable place to be coming from. But I wish you’d retract the anti-Semitic insinuation. It’s beneath you.

I’ll retract it if someone can explain to me why it’s permissible to presume that Thompson is a thoughtful, talented fellow at the mercy of his cultural inheritance and its attendant flawed assumptions, but we can’t do the same with Domingos Isabelinho or anyone else. Turnabout is fair play, even in a witch hunt. And at the point that we’re citing a select fraction of the available evidence as proof of malfeasance that was clearly not intended by the author, a witch hunt is what we have.

Habibi was conceived as a response to Western racism. We can all form our own conclusions on how successful the work is, or if it contradicts itself by reinforcing racist ideas, but part of its value is to inspire this very conversation. To not engage the work by examining its imagery and how it fits into the history and political realities it addresses (or fails to address) would be a disservice to a major release in the graphic novel medium.

Nadim talks carefully about his concerns, and bases them in a the images and narrative before him. He includes discussion of Thompson’s defense, and explains explicitly why he feels that Thompson, despite best intentions, has perpetuated certain Arab stereotypes. Thompson says himself that he is dealing with charged issues, and trying to rework Orientalism. Because he says that is what he is trying to do, does it automatically mean that we must assume he has succeeded? If part of what he is doing is thinking about these tropes, then it seems justified to talk about how successfully he has dealt with those tropes. Nadim is talking about an issue that Thompson explicitly raised.

Domingos on the other hand said nothing about Eisner’s Jewishness. Your imputation of anti-Semitism is based on nothing but the fact that Domingos is not a fan of Eisner, and that Eisner is Jewish. That’s not turnabout. It’s despicable trolling, which mirrors some of the worst excesses of our current political discourse. And, as I said, it’s really beneath you.

I’m happy to have a defense of Habibi aired. I’d print an article by you about it on this site, if you wanted to write one. But you do yourself and your cause no favors by displays of wounded bile such as this. If you think Habibi successfully navigates the issues that Nadim raises (and which Thompson has said he was attempting to navigate) then explain why and how he does so. As it is, your inability to see the difference between what you did and what Nadim did doesn’t buttress your authority; it undermines it.

Franklin, Intent isn’t magic, as they like to say in my neck of the woods. As an artist, I often attempt to create a certain effect. Just because I tried to move people to laughter doesn’t mean I’m necessarily funny.

So it is with any art. Nadim goes out of his way to credit Thompson with good intentions. But Arabs = slave traders and raping beasts is a story cliche in the Western world. Any artist who works within a specific genre should be aware of that genre’s cliches and tropes, if they’re going to create a story that works.

Think of it this way. If I wrote a mystery and ended it with the detective saying, “I don’t know who did it. It sure is a puzzler,” my audience would be well within their rights to go ‘what the fuck?’ I’m not absolved of knowing and understanding my audience’s expectations just because I’m trying to make a piece of art so beautiful it will change people’s minds about an important political issue.

What I got out of Nadim’s review is genuine regret that such a talented artist wasted said talents on the bones of a story that sucked and that if Thompson had done more research, he might have succeeded in creating a more successful story that did overturn Western ideas of racism. What Thompson wanted to do and what he succeeded in doing may vary depending on the person who reads the work, just as in any art, but I think Nadim was very clear about the images and specific story lines that led him to his conclusions. I’m not seeing any counter-arguments that are as textually or imagery based.

I feel like a basic review of how racism works might also be in question for some here. To say “I don’t want to talk about race” is to ignore that racism exists. It is not a solved problem. Maybe you would like to judge every individual artist and their individual cultural productions in a hermetic vacuum, but that’s not the world they exist in, and in the world we live in, Arabs and Muslims are subject to pretty horrendous discrimination on a daily basis in this country in a way that white Christians are not, and there is a long history of Arab and Muslim countries being fucked over by white Christian ones. Thompson’s work needs to be read in that context, as all art does– in the context of the world we live in, not in the world of the author’s good intentions.

Vom wrote: If I wrote a mystery and ended it with the detective saying, “I don’t know who did it. It sure is a puzzler,”

I’d read it. Kind of reminds me of Trent’s Last Case ( http://madinkbeard.com/archives/trents-last-case )

Whoops; missed your comments Steve.

Nadim’s talked about Herge at greater length elsewhere. His essay here maybe fleshes out his problems a little. You might also check out his tumblr which chronicles Nadim’s pursuit of Tintin around the world.

JDL, nobody said Thompson couldn’t talk about race or Orientalism. He started a conversation about those issues, we’re continuing it. You’re attempting to shut it down. If your aggrieved flapping were at all effectual in this regard, you might be guilty of censorship. Luckily, it is not, and you aren’t. So carry on.

Also…you really think that no one should ever object to anything anyone says about other cultures? Really? Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda is cool? American antebellum racist propaganda is great, and abolitionists shouldn’t have objected to it? Is that really the stance you want to be taking?

Allen, by all means, let’s examine the imagery. But that’s not what’s happening when a writer who describes himself as “a college graduate with a degree in Politics, who is now travelling around the world with a research grant to study the colonial implications of The Adventures of Tintin” reads Habibi and finds evidence all over the thing for colonialism. That’s forcing art through your personal strainer and criticizing the ensuing mush.

Noah, with apologies for what is going to come off as further trolling, I never accused anyone of anti-Semitism. It’s true, I didn’t. What I did was set up just enough associations to make it seem like I was. Was that dishonest? You bet, and it’s dishonest for the same reason that Damluji’s assertion that a redacted version of Aladdin played a part in Thompson’s vision is dishonest. There is not a shred of evidence for this, and I don’t care how bad it looks to Damluji. He is trained to find such things, even in the patterns of tree bark. That he found them in Habibi is neither surprising nor notable. As I demonstrated, anyone with sufficient rhetorical chops and bad faith can do this. The indignation you rightfully directed at me could be just as rightfully directed at three or four points of this essay. The greedy sultan was a stereotype? What did the benign sultan in Aladdin do for human progress? As an artist, you’d be an idiot to try to win this impossible game. In any work of sufficient magnitude or charged material there will always be a lapse that a critic like Damluji can exploit. Come to think of it, maybe the only way to win that game is to lose on purpose, which explains how Holy Terror comes into existence.

Thank you for the invitation to contribute an essay. I may take you up on it. Habibi has an obvious theme of heroes shaking off claim after claim of ownership upon their persons. It has an anti-colonialist message, if anything, but since Damluji has an axe to grind, Andrew White and who knows who else isn’t going to read it. That’s a shame. But I’m not sure how to do it in a way that convinces, say, Ethan. If I claim in this forum that the rape, nudity, and characterizations are all necessary to Habibi, and all I get out of it is a basic review of how racism works – sexism, too, because we all know that’s coming – maybe I shouldn’t bother you further.

Vonmarlowe, you’re “not seeing any counter-arguments that are as textually or imagery based” because Damluji has been careful not to admit them. I would have found this essay more persuasive if he had. He thereby might have come to a conclusion that was not a picture-perfect example of academic postmodernist boilerplate, and it would have told us something interesting.

Hey Franklin.

Okay, so you’re admitting you’re trolling to make a point. Please don’t do that. Even you are admitting that Nadim believes what he’s saying. That’s a basic level of honesty that I’d really appreciate you striving for if you’re going to comment.

You’re proposed post sounds great; I do hope you’ll take me up on it. I don’t know that convincing people is ever really the point of exercises such as this. Different perspectives can give people on any sides of a debate a better understanding of their own position as well as of others. And certainly there are tons of people who like Habibi, so it’s not like you’d be met with a hostile reception entirely, I don’t think!

Your characterization of Nadim is really bizarre to me. He talks about lots of things he likes in the book. In addition, his essay is really pretty devoid of theoryspeak; it’s very straightforward and easy to read. I guess you’re coming from where you’re coming from, and if the mere hint of “postcolonialism” makes you see red, it makes you see red…but it seems like your ire might be better directed at Suat’s unambiguously negative essay, or at my more unambiguously theoryish take on Gaiman/Russell’s Orientalism, rather than at Nadim’s piece. I mean, I really get the sense that Nadim would love to be convinced that Habibi handles these issues well; he seems genuinely pained at his conclusions.

I should add…I’m pretty open to the idea that exploitation narratives with rape and nudity and so forth can have feminist connotations. I Spit on Your Grave is one of my favorite movies — not that it’s not misogynist in some ways, but it’s really smart about gender. I mean, Said talks about the ways in which Kipling or Tarzan have interesting things to say about the colonial experience. I’d be pretty thrilled if you could convince me that Habibi is as good as some of Kipling’s writing….

Hey Franklin, chill. I am perfectly fine with you or anybody criticizing my writing, but don’t try to make larger assertions about who I am and what kind of axe I am grinding. I respect that you are entitled to your own thoughts, just try to understand attacking me instead of my opinions isn’t a good look.

I included my personal inventory at the top to give readers precisely a context as to where I was coming from in my review. For you to be enraged that coming from that position I am drawing these points feels like you are missing the point. Are you upset that the lens of Orentalism exists? Just how I am handling that framework? That I am being critical of art? Again, engage with the points made if you are going to engage, but please avoid the ad-hominem attacks.

Actually, Franklin, I mean that *you* or JDL could write, for instance, “But on page 47, Thompson trumps the cliche when he shows [description of imagery and plot].” So far, all I’m reading is an argument that Nadim isn’t supposed to make these arguments. I don’t find that very convincing.

I’ve got no dog in this fight. I like Thompson’s inks. I think the story, as explained to me by Suat and Nadim, sounds like a cliched retelling of some pretty stock and offensive tropes. You see something totally different, then explain why and support it with the text and imagery. Telling me that Thompson is a great guy or it’s not a winnable fight isn’t convincing me to reconsider whether I want to read this tome.

Derik, I’m still bitter about the Lady and the Tiger, dammit. I might check out Trent’s Last Case, though. Sounds interesting!

Nadim, you didn’t complain about cultural appropriation when Joumana “I DON’T HAVE TO STAND BY AND WATCH!” Medlej put a magic-powered D-cup ninja into a tight bodysuit and sent her out to beat up bad guys with assault rifles and glowing red eyes. You worried that you were going to encounter it the whole time you awaited the arrival of Habibi, and lo and behold, you found it! And there you found a cast of stereotypes and an overly sexualized protagonist and the wooden dialogue that proved it. Clearly, cultural appropriation is only a problem for you when certain people are doing the appropriating. Let’s start with you telling me which people those are.

Thank you Nadim! This is a beautifully written and gentle piece of criticism, and is helping me wrap my head around a piece I’m trying to write about Habibi. I find its strictness to an unusual amount of melodramatic tropes really troubling. Reading Habibi as an Orientalist text considers a lot of these same awkwardnesses, and in a really urgent way.

This is what I’m writing about, but I think its relavant enough to bring up here–

Most theories of melodrama are reconciled to the fact that only a few hallmarks of melodrama appear in each example. For good reason: melodramatic trends are super diverse, including among other things exploitative thrill sequences, disconnected causality, the ejection and return to the rural homespace, the power and corrupting influence of urbanity/technology, the suffering body, and capitalism. There’s no perfect example that encapsulates all melodramatic tendencies. Habibi comes pretty damn close. It even covers male castration, which already has a really sordid history with depictions of black male masculinity.

Reading Habibi up against the theories of Linda Williams or Ben Singer, I found that two diverse definitions of the form/structure dovetail perfectly to describe the book.

And why is this problematic? A few reasons. For one, it makes me uncomfortable in the same way that Crumb’s Genesis does. Here is a book that will be given the opportunity to cross over to a non-Comics reading population. Comics creators are capable of the same rigors of research, consideration, and sophistication as any other creator, but I’m not sure this book puts our best foot forward.

Thank you! I’d love to send the piece by when I’m done with it! And I’m sorry I’m posting this at a kind of awkward time in the comment train.

Hi Kailyn, thanks for your refreshing comment! I think you have the basis of a really interesting critique here, and I would certainly love to read it when you are done. “Melodrama” is particularly useful vocabulary to address a lot of the tension that Thompson creates in Habibi. Furthermore, you can definitely read his melodramatic tendencies as the logic that ends with him relying on such heavily recycled stereotypes.

I really agree that part of what makes Habibi so problematic is the reality of its crossover appeal. This is a book you will find in both indie comic shops and Barnes & Nobles. It will most probably end up on year-end lists from non-comics people. So yes, please do send me your piece when you are done!

Right. Like you said, Nadim, you included your personal inventory at the top. I recognize that inventory as the conformist pieties of academic postmodernism. This is why I doubt that you could have reached different conclusions about Habbibi if you tried. You formed them before you read it. The object of those pieties isn’t to honor the work under discussion, it’s the public display of liberal-left virtue. Oh, the stereotypes! Oh, the lamentable eroticizing of the female character! But there’s no liberal-left virtue in going after a brown woman for doing the equivalent, and the public agony turns off like a light switch. To be clear, I’m not opposed to liberal-left virtue, but to piety.

Maybe I should compliment you for finding anything to like in Habibi at all. Several years ago, one of your academic postmodernist coreligionists told me that I was not allowed to appreciate Dutch still life painting without feeling sorry about Dutch involvement in the slave trade. But perhaps not. The last time I flayed one of your ilk at any length, she started by claiming to like the art, and then proceeded to take shots at the surrounding culture of the work based on cherry-picked evidence. So maybe this is the contemporary way of doing business.

It would be too much to call you a hypocrite, but you have embraced a discipline which traffics in hypocrisy and relies on extremely tendentious interpretations of art and history. If that sounds harsh, at least I stop short of calling you a jackal.

Franklin, the jackals Eddie is referring to are me and Suat, I’m pretty sure. He’s had some back and forth with us before. He seems to think Nadim’s piece is thoughtful and interesting. If he’s grouping Nadim in with the jackals, I suspect it’s just guilt by association rather than a direct insult. (I’m kind of pleased to be a jackal myself.)

Nadim talks about Joumana Medlej here in case folks wonder what Franklin is referencing. I think I agree with Franklin on this one; that strip seems badly drawn and cliched to me (though they seem like stupid superhero cliches rather than stupid Orientalist cliches — and of course I’m just looking at a few pages, so it might be better if I read the whole thing, same as with Habibi.)

Franklin, you realize your lone-aesthete-against-the-world schtick is every bit as predictable and conformist as anything you’re accusing Nadim of, right? And it seems particularly odd when dealing with Nadim, who is unfailingly polite and didn’t even dislike the book that much. I guess it’s hard to get out of the defensive crouch once you’re in it though.

“The object of those pieties isn’t to honor the work under discussion,”

I don’t know that the object of anyone should be to honor the work under discussion. If it deserves honoring, honor it by all means. But criticism shouldn’t be about reverence, and every work of art doesn’t deserve obeisance. I mean, your goal doesn’t seem to be to honor Medlej’s work, right?

And…your interpretation of art and history is extremely tendentious as well, yes? Otherwise we wouldn’t be having this tendentious argument. Maybe you’re on firmer ground re tendentiousness when you argue against feminist psychoanalytic approaches or whatever — but Edward Said is really clear, and his work isn’t at all counterintuitive. Nadim’s piece is very straightforward — and, indeed, builds on Thompson’s own insistence that he’s using Orientalist tropes. Given Thompson’s discussion of Orientalism, it seems like ignoring that aspect of the work, or claiming it didn’t exist, is the more tendentious claim (though of course you could argue that he does interesting things with the Orientalism; Caro seemed to be pointing in a possible direction to go with that argument.)

I mean…do you have a problem with Said? It’s been a bit since I read Orientalism, but like I said, it seems different than the other stuff you’ve gone off on in the past. I really doubt that Said liked or cared about conceptual art for example, and I can’t imagine he was especially fond of Lacan (if he ever thought about him at all.)

—————————

Franklin says:

…Like you said, Nadim, you included your personal inventory at the top. I recognize that inventory as the conformist pieties of academic postmodernism. This is why I doubt that you could have reached different conclusions about Habbibi if you tried. You formed them before you read it. The object of those pieties isn’t to honor the work under discussion, it’s the public display of liberal-left virtue. Oh, the stereotypes! Oh, the lamentable eroticizing of the female character!…

—————————–

At HU, I’ve frequently trashed arguments coming from those perspectives when I found them dubious. (Which is prettty damned often!)

However, Nadim’s critique is fair-minded (too kindly by far for some: https://hoodedutilitarian.com/2011/10/a-comment-on-the-subalterns-progress-through-habibi/ ), no mere tunnel-vision regurgitation of ideologically-based attacks, and carefully buttressed with much evidence.

Thompson is not being damned as racist or sexist (as some shrill ideologue would casually do); what we have is an explanation how, despite his best intentions, his usage of genre tropes and stereotype perpetuates the negative view of the Muslim world he effectively was working to correct in other parts of the book.

Franklin, you realize your lone-aesthete-against-the-world schtick is every bit as predictable and conformist as anything you’re accusing Nadim of, right? … And…your interpretation of art and history is extremely tendentious as well, yes?

“I know you are, but what am I,” even on someone else’s behalf, is not an adequate counterargument in an adult discussion.

“Honor” wasn’t a good choice of wording. Obviously, failed art should be called out as such. But it’s possible to dishonor good work by deciding that you’re going to have a problem with it in advance, and then making it grist for the critical mill that you run everything else through.

If I was teaching argument I’d submit the following as a negative example:

“If you honestly want to respect other cultures, you should treat them as you would you own – which can be a wide spectrum of humor, criticism, flights of fancy, etc. It’s really a shame that people seek to restrict what can be said about other cultures.”

The warrant that underlies this is as follows: Equality is the same as equivalence. The problem is, equality is not the same as equivalence. To treat different cultures with an equal level of respect is a good thing, to treat different cultures as though the were equivalent, to not alter your theoretical lens/to maintain a rigid approach to reading/to not contextualize,etc., is to ignore the very responsibility to the text for which Franklin seems to be advocating.

““I know you are, but what am I,” even on someone else’s behalf, is not an adequate counterargument in an adult discussion.”

If you think what Nadim said is a problem, but your own argument and position has similar problems, it seems like it’s worth pointing that out. And, you know, calling me a child doesn’t exactly raise the level of discourse.

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with tendentious or counterintuitive arguments, whether yours or Nadim’s. I also don’t think that there’s anything wrong with using arguments others have used, or in connecting up with a previous body of thought, as both you and Nadim do. I actually think both are pretty unavoidable. However, if you disagree, it seems like you need to explain why your own position differs from Nadim’s on these grounds. Otherwise, your accusations just seem like special pleading.

“Obviously, failed art should be called out as such. But it’s possible to dishonor good work by deciding that you’re going to have a problem with it in advance, and then making it grist for the critical mill that you run everything else through.”

Sure, that’s reasonable. Though I disagree that that’s what Nadim did, obviously.

…to not alter your theoretical lens/to maintain a rigid approach to reading/to not contextualize,etc., is to ignore the very responsibility to the text for which Franklin seems to be advocating.

Unless it’s just a fancy way to implement a double standard. I’m not saying you’re wrong, though.

I don’t think there’s much doubt that Said thought about Lacan. He was fairly well steeped in French poststructuralist thought, though he preferred Foucault to folks like Derrida or Lacan.

Yeah; I didn’t mean to suggest he hadn’t read him. More that if he influenced him, it was more by rejection than anything else.

Just to be clear, I haven’t read the book so I’m not really pointing in a direction of an argument as much as posing a question for an argument that may or may not be make-able based on the evidence. :)

The classic examples I think of for “good” exoticism are things like World’s Fair pavilions and ’60s musical exotica — all trafficking in stereotypes and generalizations and even caricatures, but also, importantly, drawing on indigenous voices and crafting exotic representations that are, overall, positive, rather than dehumanizing ones. They can create interest in the outside world that’s a valuable counter to jingoistic tendencies.

I will read the book; I’m on the hook for a post in this slow-rolling roundtable. But at the moment, I think, without intending any criticism of Nadim’s use of Said’s argument, that digging a little deeper into Said might be worthwhile, as it seems like we’re moving toward entrenched positions that really are more axiomatic than anything Said himself said. I take Eric’s point (and I don’t know for sure whether Franklin has read Orientalism or not) but it seems like he might find it more palatable than most French theory — Orientalism is from 1978, and it’s much closer to a traditional textual and historical treatise than the canonical works of poststructuralism or psychoanalytic feminism (and Said’s later work.) There’s a copy of the book online, and even skimming the introduction is valuable.

It’s also interesting to note that by the 1990s, in books like Culture and Imperialism (which were much more overtly theoretical than the earlier work from the late ’70s), Said was putting forth defenses of books like Heart of Darkness specifically on the grounds that Conrad was self-aware, that is, even though he couldn’t really think outside of the discourse of Orientalism, he perceived the places where it was insufficient, and that perception comes across in his writing.

I think the important next question, therefore, is not whether the book traffics in orientalist stereotypes, since Thompson has acknowledged that and Nadim does a good job of highlighting them, but whether it does anything interesting structurally with those stereotypes, whether and how it deepens our understanding of them. His right to use them is rather besides the point, IMO. Of course he can use anything he wants, but is what he does with them smart?

I haven’t seen any arguments that he does anything particularly smart with these tropes, in the sense of the type of insight that Said identifies in Conrad. It seems to me, on the surface, that a “coyboys and indians” perspective isn’t all that likely to get to those types of profound dissections of the sociodynamics of Western prejudice. But that doesn’t mean he won’t surprise me! An argument that he accomplishes something that smart is what I’d like to see, from Thompson and people who appreciate the book, and it’s what I’ll be looking for when I read it.

———————-

Nate says:

…To treat different cultures with an equal level of respect is a good thing…

———————–

Um, but do all cultures deserve “an equal level of respect”?

From Tim Kreider: http://www.thepaincomics.com/It%20May%20Not%20Be%20a%20Perfect%20System.JPG

I can understand rejecting oversimplifications about larger groups with greater variety (“Muslims think women should be treated like chattel”; “Americans are warlike and materialistic”), but damned if I’m going to treat Islamist fundamentalists or the African peoples who practice female genital mutilation (whatever good points they may have) as equally deserving of respect as, say, Quakers or French-Canadians.

Treating with respect doesn’t necessarily mean approving of everything they do.

I’ve turned Caro’s comment above into a post here if folks want to continue the conversation over there.

Mike — Actually, there *is* a book called “Occidentalism,” by Ian Buruma and Avishai Margalit. It’s quite good. It’s short, but discusses all kinds of ‘anti-modern’ and tribalistic movements, going back to Russian and Eastern European movements hundreds of years ago, when it was Eastern Europeans who were the “exotics” to the west.

Although I’m certainly guilty of using Arab-ish/exotic fantasy settings in my own work, reading Habibi, I was skeptical of Thompson’s idea that the key to understanding between West and East is understanding of a shared religious tradition. You can go that way, sure, and if I was someone from a Fundamentalist Christian background who had written extensively on my (former) faith, I might feel that the answer is to play around with Islam the way I had played around with Christianity in my other works, but as a political statement, I think it’s a lot better to ‘humanize the other’ based on shared humanistic/secular values and common humanity rather than on shared religious tradition. Said continually defended both Islam and Arabs, but he himself wasn’t a Muslim or raised a Muslim, and despite his vigorous defense I’m pretty sure he managed to avoid conflating Muslims and Arabs, something which 99% of Western commentators do. (And a great deal of Arab/Muslim commentators as well, admittedly.)

Anyway, though, it makes sense for a fairy tale to draw inspiration from the magical realism of religion rather than from the harsh reality of politics… and Habibi does make a sort of liberal-ish political commentary in the second half, as all these white guys start to creep into the narrative, and prove to be the ‘power behind the throne’ of Wanatolia…. but along the way, we’re still treated to hundreds of pages of child marriage, rape, rape, rape, harems, harems, rape and basically all the typical Western stereotypes/tropes about Arab & Muslim cultures. I don’t fault Thompson for his guilt/power obsession with male sexuality, any more than I would fault Charles Burns for Black Hole, nor do I blame him for having a lot of cheesecake in his books, but reading Habibi, in which he keeps thrusting these images of negative male sexuality upon the figures of these Arab-ish characters, I kept thinking “Admit it, YOOOOOUUUU ARE THE SULTAN, CRAIG THOMPSONNNNNNN” -_-

Re: “treating with respect,” I have trouble with arguments that people must ‘respect’ anything. The comics of Ivan Brunetti and Johnny Ryan are as disrespectful and insulting to religion as anything I can imagine, but they’re out there — not on mainstream TV or emanating from politician’s lips, but they’re not being burned and suppressed by the authorities and by angry mobs (well… at least not the last time I looked at the clock. Fingers crossed).

To move back on the time scale of what’s acceptable… there used to be small communities in Britain (and probably America) where, if you didn’t go to church on Sunday, the preacher would walk over to your house and whip you out of bed until your went to church. It was obviously considered ‘disrespectful’ to him that you didn’t go to church. This is one extreme to which ‘respect’ can lead.

Another example: Lenny Bruce. Lenny Bruce went to jail repeatedly for his comedy routines which satirized religion, among other things. In the 1950s and early 1960s this was not so common. Also, Lenny Bruce was a Jewish comedian making fun of Christianity, but Christians didn’t respond to this with a pogrom against Jews. He gradually pushed against social boundaries and he was one of the people who changed those boundaries.

Granted, Lenny Bruce wasn’t in a position of power over Christians, Lenny Bruce wasn’t bombing and invading anyone at the same time that he made fun of them. But still. I have a point here somewhere. Right — my point is that ‘respect’ is something which artists and activists have to continually push against. Artists must be disrespectful, not respectful. They should also be aware of the history of what they disrespect and of their own culpability and that of their own governments. But still. Disrespect is good.

Jason,

I’m not sure who you’re responding to re. respect, but when I said treat cultures with equal levels of respect, I didn’t mean respect in the sense of obedience (respect authority), so much as respect it enough to applaud or critique it on its own grounds. This could mean treating cultures with an equal lack of respect, but ridiculing them differently. Johnny Ryan, who I often find hilarious, is a good example of someone who treats all cultures with an equal level of disrespect, though I think he often errs on the side of equivalence. That is, each culture gets treated as though it were stupid in more or less the same way, and comes up for the same treatment as a result.

Long story short, I don’t think anybody is obligated to respect anything, or anyone. And they’re especially not obligated to respect authority. But I think that when you choose your target, you need to be sure your lack of respect comes not out of unacknowledged prejudices, intellectual laziness, or the conflation of a cultural practice with a culture in its entirety. Carlin, by the way, was really good at this because he possessed such a keen eye for the hypocrisies that underlie American culture and mores.

Hey Jason. It’s always a pleasure to have you show up here. (And you as well Nate!)

I feel like especially in comics there can be almost too much respect for a lack of respect? There’s an idolatry to pissing on idols too. Not that I’d want to enforce reverence for world religions at all…but I think among aesthetes in the U.S., knee-jerk reverence for irreverence is much more prevalent than knee-jerk reverence for anything else.

I think Johnny Ryan is actually on top of that contradiction too. I wrote about it here.

Hi Noah and Nate! I guess I was responding to both of your comments on ‘respect’. Thanks for the link, Noah — you’re definitely right that nihilistic black humor is its own sacred cow.

Forgive me for the rant which had nothing to do with ‘Habibi’, which I have some problems with for reasons I mentioned in my previous post. The word ‘respect’ just set me off. I was involved in a conversation awhile back with some random people somewhere, and we ended up talking about the Molly Norris case. One guy, who apparently was a right-wing Catholic of some sort, said basically “Serves her right” — he apparently thought it was Molly Norris’ just desserts to get death threats for making fun of Islam because it pissed him off when people made fun of his Catholicism, so he understood where the threat-makers were coming from. I think his words were “That’s the thing — it’s all about RESPECT!” So, I sort of wimpily extricated myself from that conversation, thinking all the while of Ivan Brunetti’s work stories in some issue of “Schizo” where his Christian coworkers are threatening to beat him up so that he can’t poison young kids’ minds with his atheism. This is obviously just some anecdote, but that’s what I think of when I hear defenses of ‘respect’.

Man, I’m just full of off-topic rants today! -_-;;

I’m not much of a fan of Ivan Brunetti, and I have a fair bit of respect for Christianity…but it does seem like wishing pain on anyone, maybe especially your enemies, is more disrespectful of Christ than some random gag.

Pingback: Graphic Novels Looking East, Looking West | Arabic Literature (in English)