This is part of a roundtable on The Drifting Classroom, and also part of the October 2011 Horror Manga Movable Feast.

__________________

“Mine is a world without logic. Adults bring scientific rationality with them. I don’t have room for that.”

—Kazuo Umezu

The strongest theme in the creations of Kazuo Umezu (1936-), by which I include his public image and performance art as well as his manga, is the fascination with and glorification of childhood. Umezu has cultivated an image as an eternal man-child, as a man who made his name drawing children’s and horror manga and still acts like a mischiveous child himself. “I’m writing about myself in a way. I don’t want to be an adult and ‘grow up,'” he said in an interview with Tokyo Scum Brigade. He’s also said that he eats as little as possible because reducing your food intake is the only scientifically proven way to extend your life. Perhaps it worked, since even into his forties and fifties he had a nebulously youthful appearance, helped along by his Harpo Marx mophead of jet-black hair and his childlike wardrobe, such as his characteristic red-and-white striped shirt. Today, although age has taken its toll, he still lives in Pee-Wee Herman-like splendor, and after the end of his manga career in 1995 (due to tendonitis) he has returned to his early alternate dream of being a talent/celebrity, like in the 1970s when, fresh off the success of his gag manga Makoto-chan, he created and sang in the “Makoto-chan Band.” In the sixteen years since his retirement from manga, he has sung Paul Anka’s “You are My Destiny” in English on Japanese TV, worn a boa and a flower in his hair at a dinner celebrating his 55th anniversary as a manga artist, and even painted his house in red and white stripes, leading to a failed legal challenge by his neighbors. In Japanese interviews, he has claimed he’s a virgin; others have suggested that the glam-loving, apparently celibate mangaka is a “confirmed bachelor” in the old sense. Like Michael Jackson, or Dave Sim, he is an artist whose personal eccentricities inspire as much commentary as the work itself; in Umezu’s case, he apparently loves the spotlight, and it is hard not to want to study Umezu’s manga and Umezu in the same eyeful.

The strongest theme in the creations of Kazuo Umezu (1936-), by which I include his public image and performance art as well as his manga, is the fascination with and glorification of childhood. Umezu has cultivated an image as an eternal man-child, as a man who made his name drawing children’s and horror manga and still acts like a mischiveous child himself. “I’m writing about myself in a way. I don’t want to be an adult and ‘grow up,'” he said in an interview with Tokyo Scum Brigade. He’s also said that he eats as little as possible because reducing your food intake is the only scientifically proven way to extend your life. Perhaps it worked, since even into his forties and fifties he had a nebulously youthful appearance, helped along by his Harpo Marx mophead of jet-black hair and his childlike wardrobe, such as his characteristic red-and-white striped shirt. Today, although age has taken its toll, he still lives in Pee-Wee Herman-like splendor, and after the end of his manga career in 1995 (due to tendonitis) he has returned to his early alternate dream of being a talent/celebrity, like in the 1970s when, fresh off the success of his gag manga Makoto-chan, he created and sang in the “Makoto-chan Band.” In the sixteen years since his retirement from manga, he has sung Paul Anka’s “You are My Destiny” in English on Japanese TV, worn a boa and a flower in his hair at a dinner celebrating his 55th anniversary as a manga artist, and even painted his house in red and white stripes, leading to a failed legal challenge by his neighbors. In Japanese interviews, he has claimed he’s a virgin; others have suggested that the glam-loving, apparently celibate mangaka is a “confirmed bachelor” in the old sense. Like Michael Jackson, or Dave Sim, he is an artist whose personal eccentricities inspire as much commentary as the work itself; in Umezu’s case, he apparently loves the spotlight, and it is hard not to want to study Umezu’s manga and Umezu in the same eyeful.

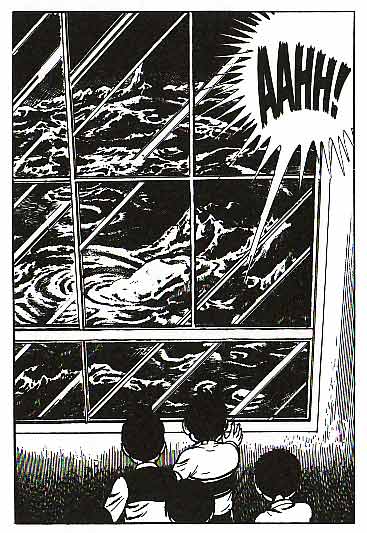

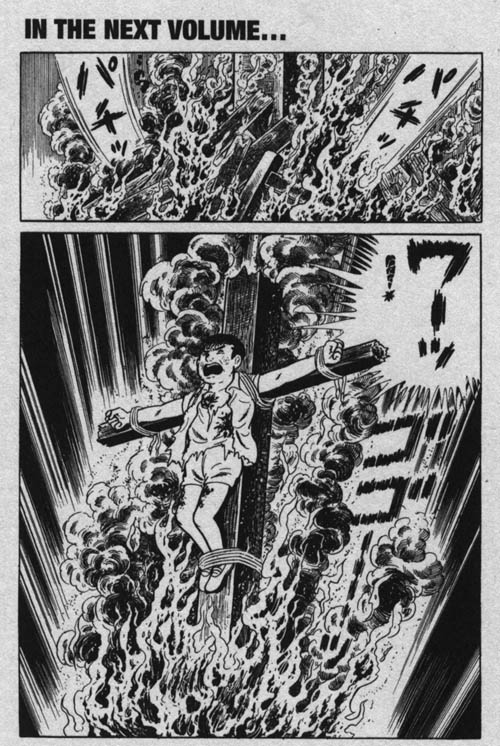

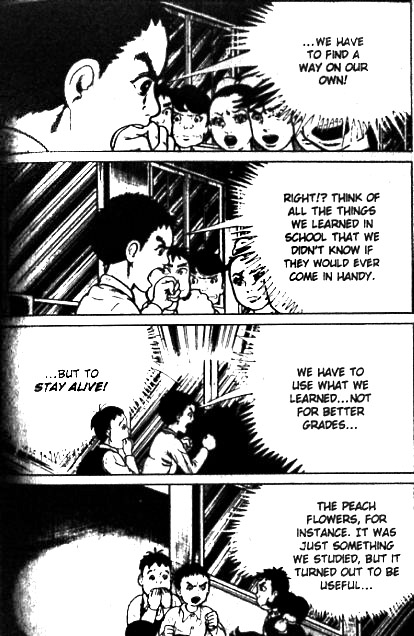

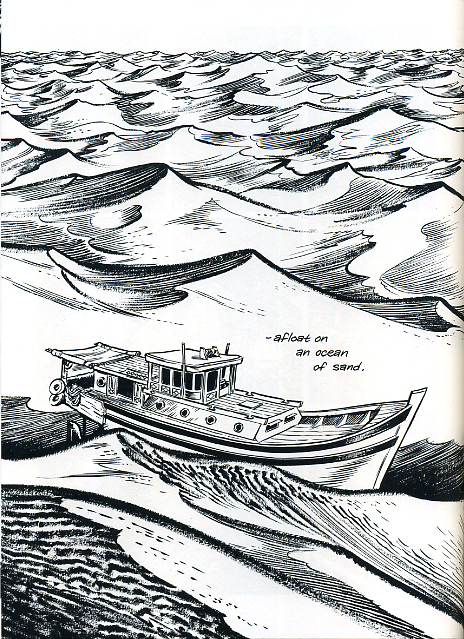

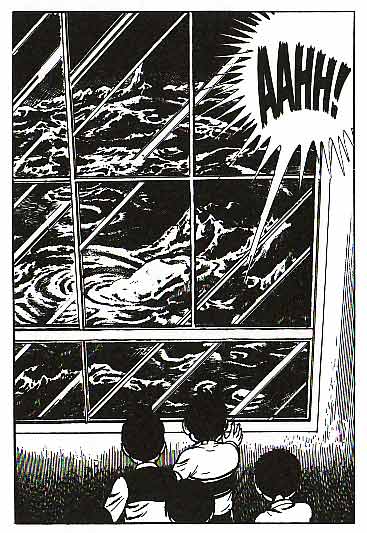

The Drifting Classroom (1972-1974) is his favorite of his own works, along with My Name is Shingo (1982-1986) and Fourteen (1990-1995), which unlike Drifting Classroom were published in a magazine for adults. Drifting Classroom, from the premise, is a pure children’s adventure fantasy: an elementary school is suddenly transported into a future postapocalyptic wasteland, and after all the adult authority figures quickly die off, the students must struggle to survive on their own. It’s a wonderful “put yourself in their place” scenario, a survival horror story filled with the kind of details that would make Shonen Sunday readers look through their classrooms and imagine what objects they could use to survive Umezu’s apocalypse: the students must find food and water, form a rudimentary government, deal with internal and external crises, and finally, try to find a way to go back home.

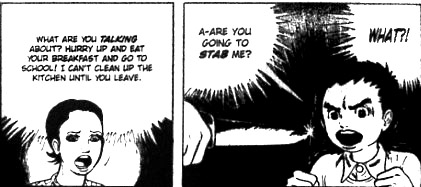

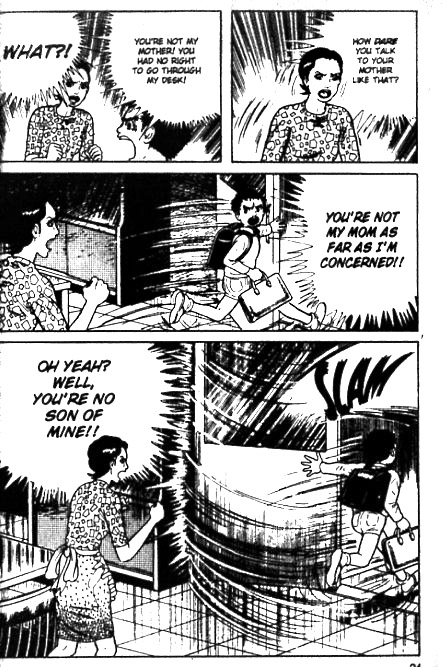

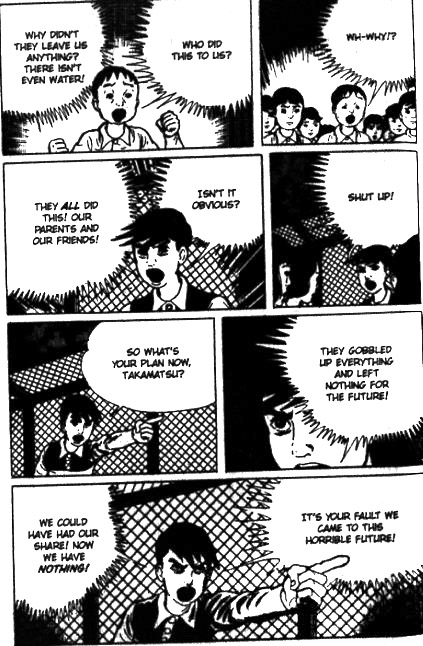

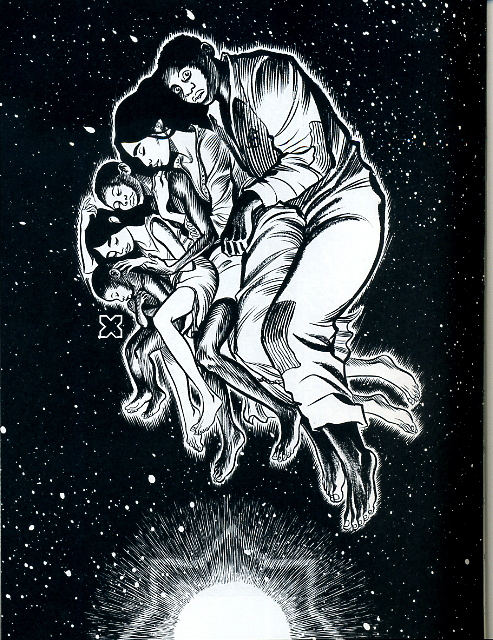

In short, the children must grow up and become responsible…they must become adults, something Umezu makes explicit in a subplot where the sixth graders volunteer to become surrogate parents for the homesick 1st graders to keep them from completely falling apart. Kazuo Umezu remembers that when you’re a kid, a year’s age difference is massive, and it’s the 6th graders (the kids closest to the target audience of Shonen Sunday magazine) who are most humanized in Drifting Classroom; there’s only a handful of named 5th graders, and the 1st through 4th graders are mostly a hapless mass of “little kids.” Sho, the 6th grade main character, starts the manga as sort of a brat, waking up late and yelling at his mother before leaving the house in a huff. Over the course of the manga, which is told mostly from Sho’s perspective as a letter written to his mother, he has endless opportunity to wish he had behaved better. One way in which Drifting Classroom is a very classic children’s story is that it’s full of moral examples, presenting many scenes in which the heroic, idealistic Sho (whom Ng Suat Tong rightly described as a “saint” in his article on Drifting Classroom in The Comics Journal #233) chooses the right path in some moral crisis, as opposed to the other students, particularly Otomo, his rival, whose instincts are more harsh and pragmatic (“We have to figure out how to survive on anything, whether it’s polluted water, poisonous food, or human flesh!”) In keeping with the common Japanese (and human) idealization of the warmth and home and motherhood, Sho and the students sustain themselves by thinking of their homes and mothers (“They must have been thinking of our homes so far away, so long ago…Oh mother! I wished I could have run up to you and thrown myself into your arms!”). But in the end of the manga, instead of returning to their homes in the past, Sho and the survivors resign themselves to the thought that they will never see their parents again, and try to find a sustainable way to live: like the pilgrims on Mars in Ray Bradbury’s “The Million Year Picnic,” they accept that this alien world is their new home.

In short, the children must grow up and become responsible…they must become adults, something Umezu makes explicit in a subplot where the sixth graders volunteer to become surrogate parents for the homesick 1st graders to keep them from completely falling apart. Kazuo Umezu remembers that when you’re a kid, a year’s age difference is massive, and it’s the 6th graders (the kids closest to the target audience of Shonen Sunday magazine) who are most humanized in Drifting Classroom; there’s only a handful of named 5th graders, and the 1st through 4th graders are mostly a hapless mass of “little kids.” Sho, the 6th grade main character, starts the manga as sort of a brat, waking up late and yelling at his mother before leaving the house in a huff. Over the course of the manga, which is told mostly from Sho’s perspective as a letter written to his mother, he has endless opportunity to wish he had behaved better. One way in which Drifting Classroom is a very classic children’s story is that it’s full of moral examples, presenting many scenes in which the heroic, idealistic Sho (whom Ng Suat Tong rightly described as a “saint” in his article on Drifting Classroom in The Comics Journal #233) chooses the right path in some moral crisis, as opposed to the other students, particularly Otomo, his rival, whose instincts are more harsh and pragmatic (“We have to figure out how to survive on anything, whether it’s polluted water, poisonous food, or human flesh!”) In keeping with the common Japanese (and human) idealization of the warmth and home and motherhood, Sho and the students sustain themselves by thinking of their homes and mothers (“They must have been thinking of our homes so far away, so long ago…Oh mother! I wished I could have run up to you and thrown myself into your arms!”). But in the end of the manga, instead of returning to their homes in the past, Sho and the survivors resign themselves to the thought that they will never see their parents again, and try to find a sustainable way to live: like the pilgrims on Mars in Ray Bradbury’s “The Million Year Picnic,” they accept that this alien world is their new home.

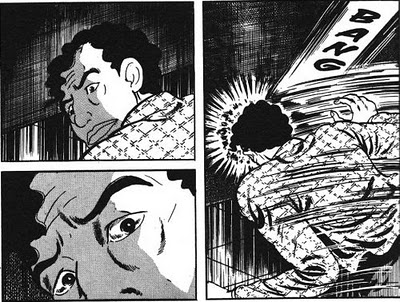

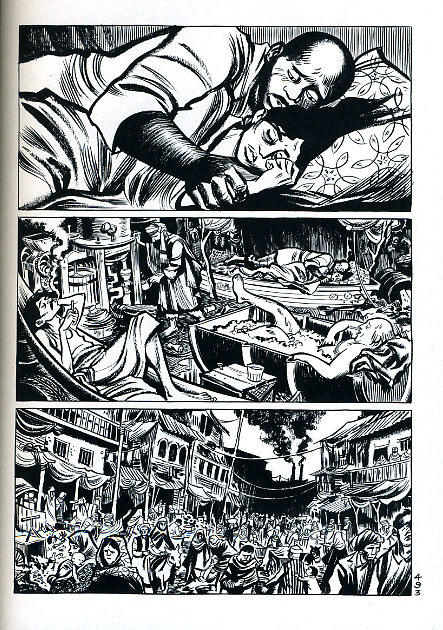

But despite the characters’ transformation from prank-playing kids to future leaders, farmers and (it’s implied in one mild romantic scene in the last chapter) husbands and wives, Umezu’s manga still enforces a clear separation between children and adults. The story does not take place over a long enough time period to show the children literally grow through adolescence, something that would seem to be outside of Umezu’s artistic abilities anyway. Whereas mainstream shojo and shonen manga from the ’80s onward have increasingly tended towards gender-blur and ageplay (something which had developed earlier in Osamu Tezuka’s proto-lolicon, cartoony-sexy character designs, as seen in characters like Kinoko in Black Jack), so that the typical shonen manga hero nowadays is an androgynous-looking 14-year-old, Umezu’s work is from a different, older tradition, where the lines between Man and Woman, Adult and Child are rock-hard. And the depiction of adults is not kind. Most of the adults transported to the future world immediately go mad or kill themselves, their rigid adult minds unable to take the impossibility of their situation. Wakahara-sensei, the kindest and most competent of the teachers, essentially takes the place of Sho’s father, who is a mere cipher. He tells his class they must see him as a parent (“Until the day we go back home, I’ll be your big brother…no, your father!”), but scarcely a hundred pages later he too goes mad and becomes a terrifying ogre, killing his offspring. The only adult who survives past the first two volumes is Sekiya, the lunch delivery man, 38 years old (just two years older than Umezu was when he started Drifting Classroom). Sekiya seemingly survives by denial, since he obstinately refuses to believe that they have teleported into the future (“Grow up! There’s no other world besides this one, you fools!”) Convinced that it’s all just a natural disaster and “American soldiers” will show up soon and save him (one of the few bits of political satire in Drifting Classroom, although Umezu is very positive towards Americans in his other manga and even in a later sequence in Drifting Classroom involving NASA), he shows no mercy to anyone who stands in the way of his survival; perhaps he survives longer than the other adults because he himself is sort of a man-child, at home neither among the adults nor the kids, combining the worst of both worlds. In one lengthy sequence he goes temporarily insane and regresses to infancy, blubbering like a baby.

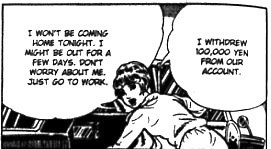

Sexual characteristics are also impenetrable barriers in Umezu’s work: adult men are drawn like walls of bricks, a tiny head on a huge suit on a huge wide chest, while his women are beautiful and slender in the ’60s fashion. Sho’s mother is one of the major good guys, repeatedly saving Sho’s life through their mother-son bond which seems to travel across time, but her obsession with her son goes beyond heroic and into scary: a mad mother-energy which drives her to do anything, to abandon her husband, cut her own wrist and attack another grieving mother, whatever it takes to save her son. Adult women in Umezu’s work are savages: pretty on the outside, but ferocious within, like the malfunctioning Marilyn Monroe android who appears briefly towards the end of the story (an indication of Umezu’s fascination with the feminine glamor icons of his youth, along with the factory robot named Monroe in My Name is Shingo, and the fact that Umezu cribbed the plot of Orochi: Blood from the 1962 film Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?). Behind that lipsticked face are slavering teeth, or perhaps the fairy-tale horror of the withered crone, the final fate of the “girl bully” who tries to take over the school, boasting of her age and maturity (“At our age, we’re more developed than you boys, physically and mentally!”)

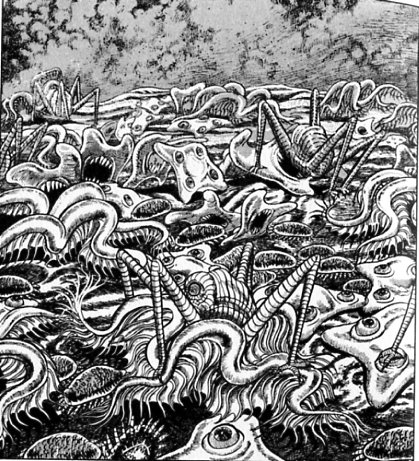

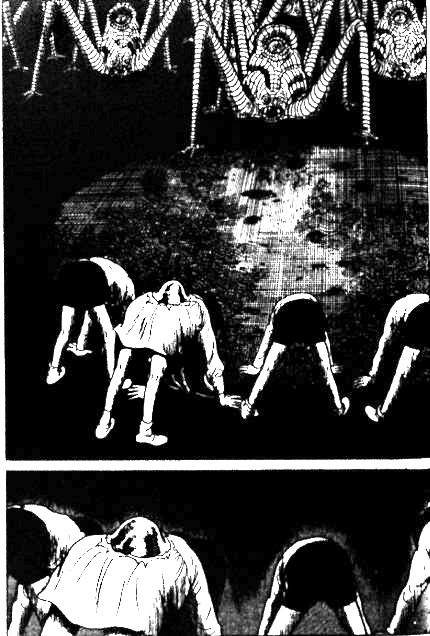

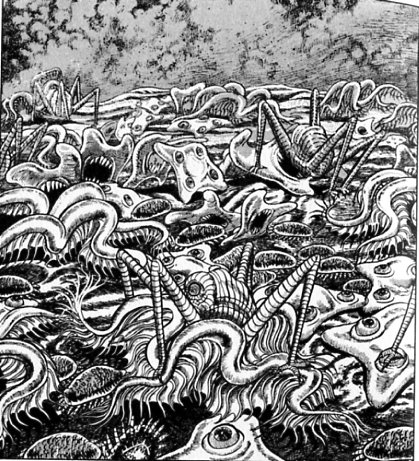

In fact, all the world—the adult world, that is—is savage, as every kid knows: a world of carnivorous, cannibal lusts, like the penultimate volume’s vision of the sea bed crawling with tentacled, starfish-like mutant monsters, eating one another and being eaten. “They’re turning into beasts!” Sho cries out in the end, as his classmates erupt in their final orgy of Lord of the Flies-esque violence, but Umezu has already literalized this in the subplot in which some of the students mutate into four-legged monsters with a face growing out of their backs—the body-intelligence overcoming that of the vestigial brain. No biological explanation is really necessary; it’s a Japanese horror trope that one can “become an oni” when driven to extremities of madness or hatred, something Go Nagai depicted in Devilman and Violence Jack, and that Umezu would depict again in Fourteen (a semi-sequel to The Drifting Classroom) when, faced with the imminent end of the world, human beings’ outward appearance starts to reflect their inner evil and cruelty.

But although the world of The Drifting Classroom is cruel, it is not random. The many often gratuitously pointless deaths, the ruthless winnowing of the student population, are not rolls of the dice in an uncaring universe as much as a long test of judgment and pain—collective, like when the students must jump across an ever-widening ravine, or individual, like when Sho must endure an appendectomy without anesthetic. The characters in Drifting Classroom never ask “Why us, out of all the people on earth? Why me?” Perhaps they feel the same sense of guilt that Sho feels throughout the story, beginning with his guilt of being rude to his mother, to another moment where he feels guilty for killing a fish (a summary of humanity’s relationship to the environment), to the slowly building but very important subplot in which he is accused of having caused the school’s time-jump by setting off a stick of dynamite under the school. This is the ultimate revelation: the school’s time-jump was not random, but a sort of punishment for a misdeed, with the sentence collectively delivered upon them all. “I wanted the school to go away! That’s why I planted the dynamite!” cries the culprit. “I always yearned for some place where there was no one,” says Nishi, sharing the responsibility for their fate. Nor is the future world’s devastation the result of mere entropy and decay, or even something something out of the average person’s control, like a nuclear war (although that was the reason for the disaster in Jun Kazami’s 1986 novelization of the manga); the end of the world must be due to human guilt, due to pollution, the corruption of humanity (adulthood) made physical. Japan’s Environmental Agency was founded in 1971, and Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster came out in the same year, so the time was ripe for The Drifting Classroom to show manga readers a blasted vision of humanity’s collective guilt for ruining the world. This devastation is all OUR FAULT, something Umezu would double-underline, again, in Fourteen, in which humanity’s evil is implicated not only in the destruction of the planet, but through an escalation of Umezu-logic, of the entire universe.

One of the impressive things about The Drifting Classroom is that it manages to balance this dream-logic with some semblance of believability. Unlike in Fourteen, a work which suffers from the aging Umezu’s degenerating artwork (and apparently his continued pride in that artwork, since most manga artists would have just used assistants), painfully slow pacing, and a willlful refusal to change his style by adding even a fraction of the realism or research Umezu’s aging readers expected in an “adult” manga, The Drifting Classroom mostly reads like a natural extrapolation of real environmental anxieties (at least as a 14-year-old might understand them) rather than a purely animistic morality-tale of nature’s revenge on human beings. In one of the early scenes, the students find a flower in the dirt only to discover it’s a plastic imitation and that only bits of plastic and polyethylene (mistranslated as “polyester” in the Viz edition, a mistake which I, the editor, embarrassingly missed) survive scattered across an earth that now looks like the surface of the moon. When the students manage to plant some vegetables, Sho has the sobering realization that they’ll have to fertilize the flowers themselves, presumably with Q-tips or something, since there are no longer any butterflies or bees. Other scenes stray farther from science, the monsters and time-travel of course, but also “educational” moments like one students’ declaration that there is a scientific basis for rain dances (“It always rains after a big fire! Soot and smoke make the clouds burst! And when we sing loud, our voices resonate against the air!”), an idea probably borrowed from a scene in Osamu Tezuka’s Phoenix. The details don’t matter as long as we get the general idea, like in the emotional but fanciful scene at the end, when the students discover that the corpses of their dead classmates have become a fertilizing bed for plants somehow growing directly out of their bodies. (“That means that they didn’t…they didn’t die in vain! Someday, this desert will turn to green fields!”) Umezu’s world is not a realistic one, even nominally; it’s a world of sympathetic magic, where a flood of water can rip off a girl’s head, where a single stick of dynamite can trigger time-travel, and where another stick of dynamite can somehow trigger both a volcanic eruption and an underground spring of water. In such a world, it’s hard to know what to make of Sho’s speech in volume 3, in which he chastises the little kids for believing a rumor that one scapegoat was responsible for their exile and if they just sacrifice that person, they’ll go home (“We (kids) know that anything can happen. That’s why we’ve managed to survive. On the other hand, because we can believe anything, we might believe things that aren’t real, and fall prey to superstitions!”) Since in the end we discover that one person really was responsible for the whole mess, in retrospect, it’s hard to blame them, but what the kids don’t understand is that one person’s sins are just a microcosm of everyone’s: we’re all responsible, and we’ve all got to be willing to sacrifice ourselves. It’s also an example of how cleverly Umezu foreshadows future events, and how deviously he, as the god of the story, upholds, then mocks, then upholds, then mocks (?) his hero’s purehearted morality.

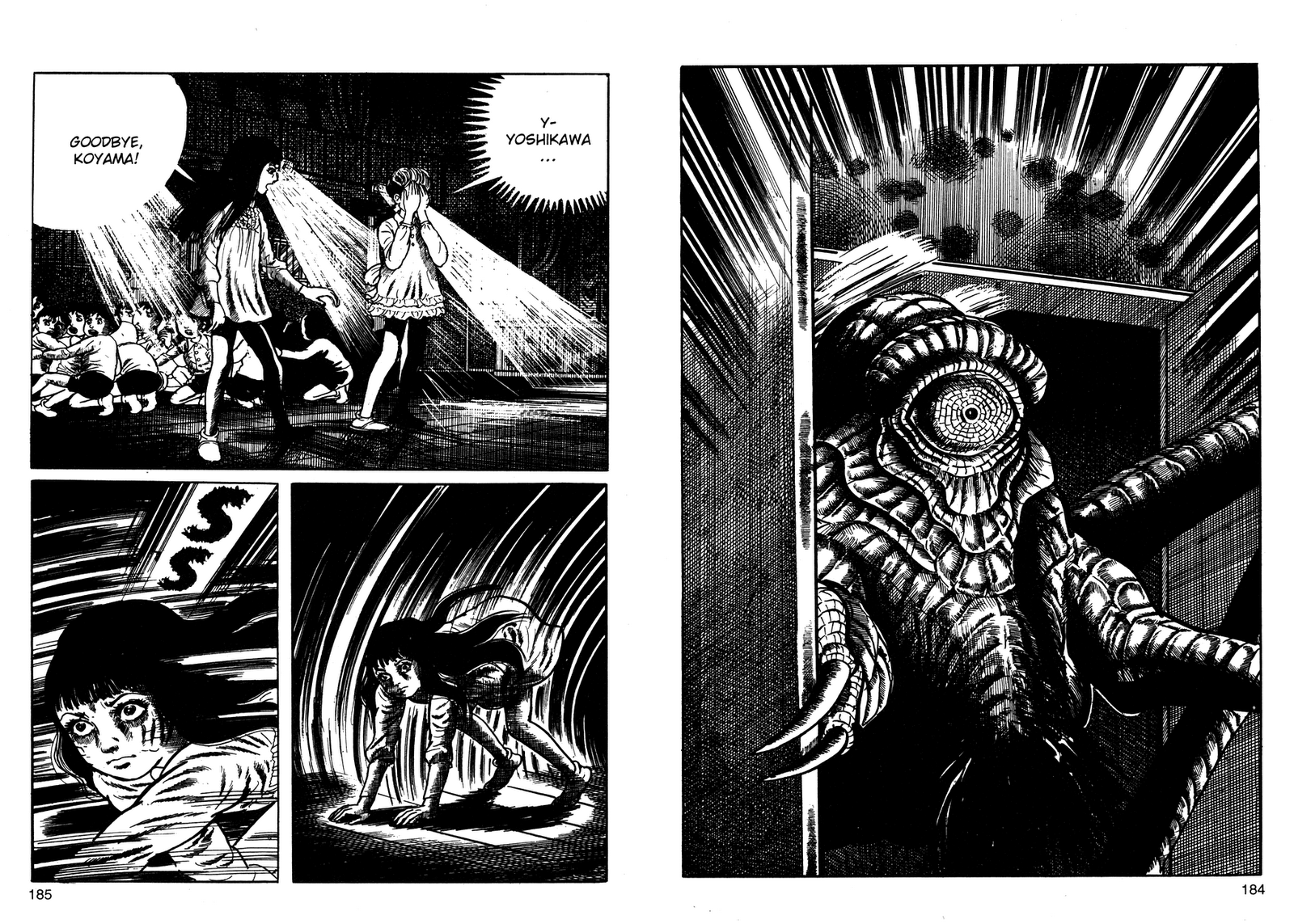

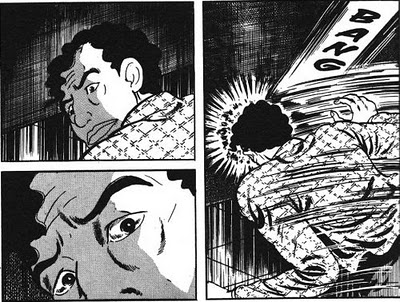

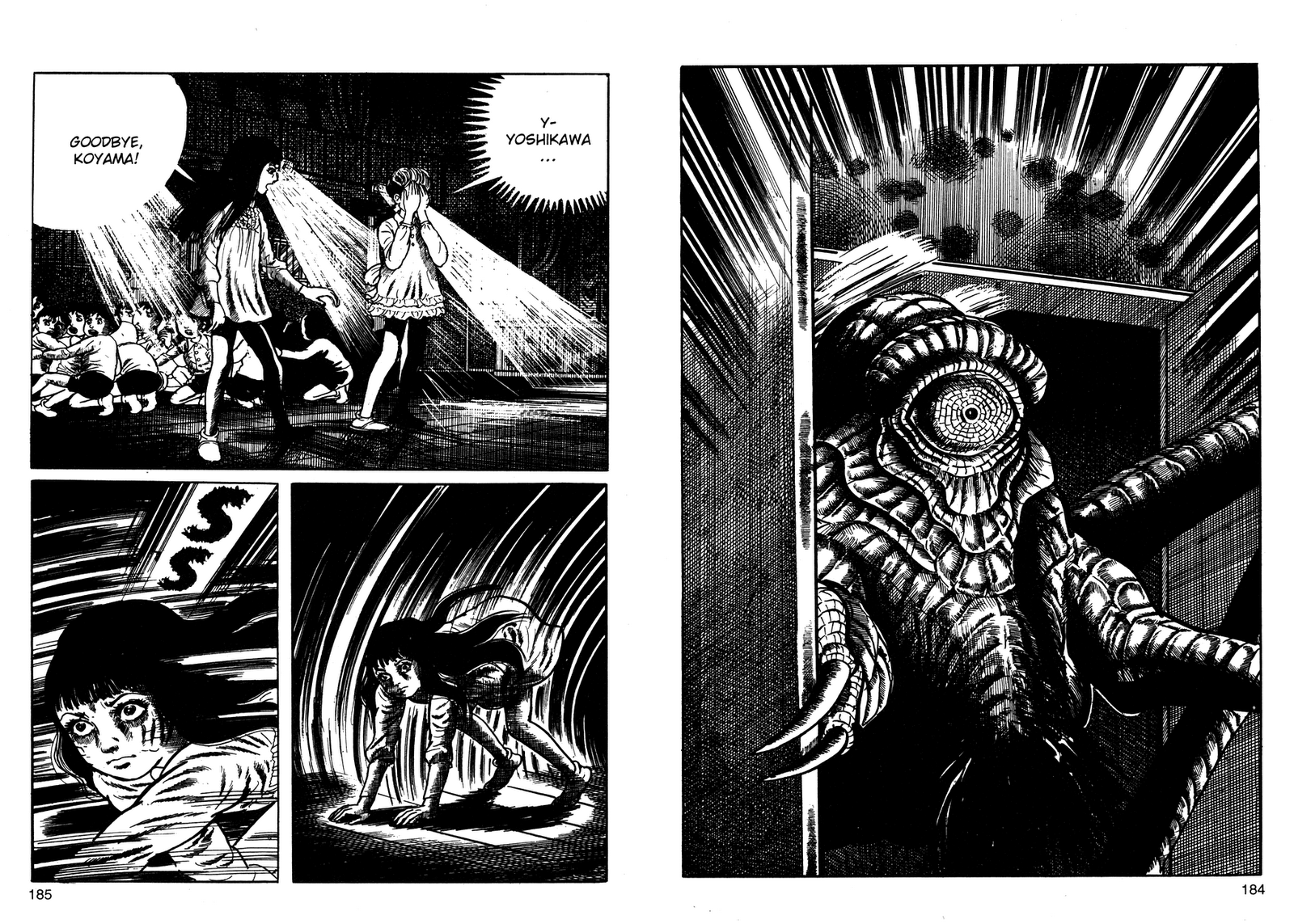

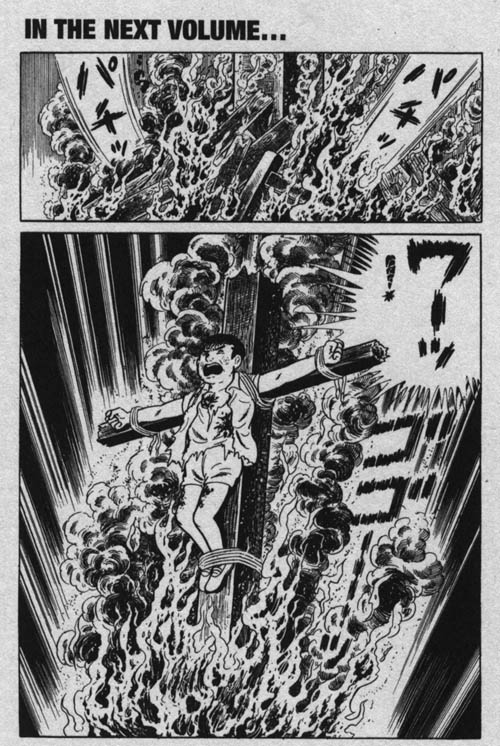

This repetition is one of Umezu’s principal tools as a mangaka. The imaginary monsters which appear in volume 3 teases and foreshadows the appearance of the real monsters in volume 7. The initial split of the school into two warring halves in volume 3 paves the way for the more violent split in volume 5 and the cataclysmic split in volume 9. Even the crucial plot element of Sho’s apparent psychic connection with his mother (irrational explanation #1) turns out to be just a buildup for the revelation that Nishi, the girl with psychic powers (and possibly Sho’s future partner and future wife-mother?), was present at all their communications and was actually the one making the connection (irrational explanation #2, which is slightly more rational, having the genre-honored excuse of psychic powers rather than simply the emotional explanation of a mother’s love conquering space and time). These repetitions come off not as mere dead ends or pointless power-escalations (“worked once, might work twice”) of the kind shonen manga is infamous for, but as deeper and deeper layers of the onion, or multiple layers of paint enriching Umezu’s themes. For a story which was drawn in 20-page segments in a commercial magazine (though most of the 20-page segments have been sewn up into longer chapters in the graphic novel edition, something no longer common in manga), and that would presumably have had to end abruptly if it became unpopular in the readers’ polls, this is extraordinarily deep plotting. Repetition of image is also an Umezu specialty: the slow, creepy, ever-increasing closeup of some shocking visual, often ending a chapter and beginning it on the same note, to grind the image into our minds (but rarely if ever just photocopying the panel, the way American newspaper story strips were eventually reduced to doing). Sometimes, particularly in his later work in the ’80s and ’90s, Umezu was criticized for the extreme slowness of his pacing; one does wonder, was volume one’s six-page sequence of three consecutive two-page spreads, showing the school principal staggering into the room with blood on his forehead, intentional, or did Umezu run out of time and have to stretch the scene out to six pages? But there are few slip-ups like this in The Drifting Classroom. His extreme visual realism and detail (even if the perspective is askew and the poses stiff) makes his dreamworld believable, the opposite of Tezuka, who used cute childish art to make his adult stories more palatable. The incredibly visual nature of Umezu’s manga makes many of his stories work even if you can’t read the text (or at least so I told myself, while I was struggling to read his manga with the tankobon in one hand and a kanji dictionary in the other); in 1997, before translations or scanlations of Umezu, Patrick Macias passed me untranslated copies of his manga like they were pornography or copies of the Necronomicon.

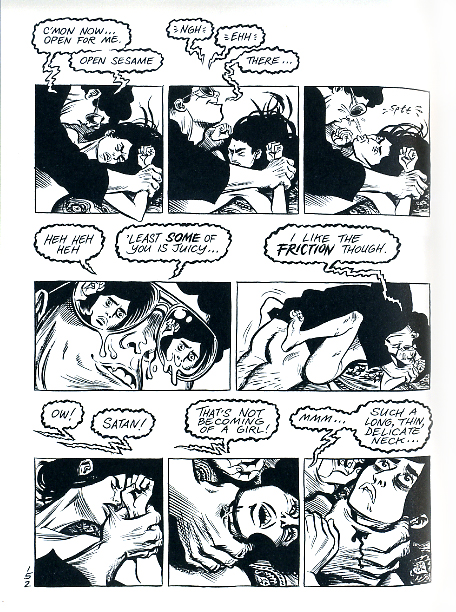

One of Umezu’s favorite artists is Salvador Dali, although Japanese fans have compared Umezu’s style to Mannerism (which according to Wikipedia, like Umezu’s work, “makes itself known by elongated proportions, highly stylized poses, and lack of clear perspective.”) Dali’s dream-logic and coexistence of grotesque opposites is very childlike, and very Umezu; for in contrast to many other artists who glorify childhood, like H.P. Lovecraft in his early works (“An artist must be always a child—that’s why I tell you never to grow up!—and live in dreams and wonder and moonlight”), Umezu does not tidy up the world of children for the sensibilities of adult Romantics. As the creator of the poop-obsessed Makoto-chan, he’s happy to mix terror with moments of childish low comedy: Gamo the genius trying to climb onstage and sliding his big egghead noggin across the floor; Hatsuta, who’s drawn like a bucktoothed gag manga character, trying to bite open a can of pineapple and shouting “Oww!” He even manages to work a baseball scene into the story, this being the days when baseball manga was king. He has a memory, too, for the casual cruelty and obscenity of childhood: the scene when the bully’s stooges strip down a kid and stamp on his naked crotch is more disturbing than the immediately preceding scenes of children being run over by cars, eaten by giant insects, throttled by homicidal adults, etc. (It might also be one reason why the Viz edition of the manga is labeled “explicit content: for mature readers.”) And yet The Drifting Classroom is much less transgressive than Umezu’s later works; it has nothing on Senrei/Baptism, when an aging woman transfers her brain into a young girl and tries to seduce an adult man, let alone some of the scenes in his later manga.

As an ironic result of being labeled “18+” in the English edition, and thus kept out of the hands of actual children, The Drifting Classroom occupies a weird space between the worlds of children and adults. In this way it’s like Umezu himself. I’d like to know what an actual 12-year-old would think of it if they read it, but as shown over and over in Umezu’s own works (Again, Baptism/Senrei, Fourteen) for an adult to try to re-enter that world and become a child again is at best comedy, and at worst, obscene horror. Like Sho’s mother, adults can watch, but not really interfere; the worlds of children and adults can never meet, except possibly (does he really think this?) in the person of a eternal child like Umezu. Even if Sho and Nishi prevail through their many trials and become sort of a couple, like the two children who raise an artificially intelligence factory robot in My Name is Shingo, Umezu can never show them “growing up.” One of the biggest concerns of the children in The Drifting Classroom, before they even worry about their own survival, is knowing whether their parents are dead. (“I just couldn’t believe that my mother had died, that she didn’t exist anymore. I couldn’t believe that could ever happen!”) The parents’ survival in the story reminds me of a possibly apocryphal quote attributed to Woody Allen: “Death is hereditary. If your parents died, chances are you’ll die too.” As long as the mothers of Sho and Yu and the others are alive, they are still children, and on some level, everything will be all right. It is this note of reassurance that “ties the present with the past,” that makes mothers Mothers and fathers Fathers, the makes The Drifting Classroom a story of guilt and exile and suffering, but not meaningless suffering.

Soap operas, it’s also worth remembering, have a history of turning rapists into romantic heroes. (Two examples come immediately to mind: Luke on GH and on OLTL. There may be more.) These shows do not stand firmly on the moral, humanistic, life-affirming side of any binary question about violence.