We’ve had several posts on race this week, so I figured I’d finish up by reprinting this piece from Comixology. I think it’s one of Jeet Heer’s least favorite things I’ve written, if that’s any incentive.

__________________________

As cartoonists go, Robert Crumb is quite, quite famous. Still, there’s cartoonist famous and then there’s rock star famous. Which is to say that for all his notoriety and the cultural currency of “Keep on Truckin'”, the Crumb image that has been seen by most people is probably still his iconic 1968 Cheap Thrills album cover for Big Brother and the Holding Company featuring Janis Joplin.

It’s somewhat unfortunate that this is one of Crumb’s defining images. Not that it’s bad. On the contrary, the inventive layout, with images radiating out from a central circle is pleasingly energetic, and the drawing, as always with Crumb, is great. Plus, cute turtle! The only thing is….

Well, it’s kind of racist.

Crumb’s oeuvre not infrequently delves into reprehensible blackface iconography. Sometimes, (as in his Angel McSpade strips) he seems to be trying, at least to some extent, to critique or mock the imagery. In the upper right of the Cheap Thrills drawing, though, he seems to use blackface simply because (a) that’s how Crumb draws black people when he’s drawing cartoons, and (b) racist iconography = funny!

The racist image in question is an illustration of Joplin’s cover version of the famous Gershwin tune from “Porgy and Bess.” The song itself, written by a Jew to capture the sound of African-American spirituals using elements from Ukrainian folk tunes, is one of America’s great cultural mish-mashes. Though its lyrics evoke the happy darky stereotype (“Summertime, and the living is easy…”) its mournful, heartfelt tune suggests a barely suppressed sadness — a weight of hardship hidden for the sake of love beneath a lullaby. My favorite take on the song is probably Sarah Vaughn’s effortlessly heartbreaking rendition. In comparison, Joplin’s hoarse bombastic reading sounds strained and clueless. The rendition is bad enough that it even becomes borderline offensive: almost the very minstrelization of black experience that Gershwin, through a kind of miracle, managed to avoid.

In that sense, Crumb’s image for the song could almost be seen as parody; a vicious sneer at Joplin’s blackface pretensions, caricaturing her as both a wannabe black mammy and as the whining white entitled brat looking to the exploited other for entirely undeserved comfort. As I said, it could almost be seen as that — if Crumb hadn’t thrown in another entirely gratuitous blackface caricature in the bottom center panel, just to show that, you know, he really is exactly that much of a shithead.

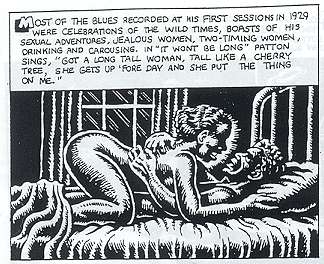

Given the grossness of the Cheap Thrills cover, it’s interesting that Crumb has, in the intervening years, gained a reputation as a particularly thoughtful interpreter of the black musical experience. His passion for 1920s-30s blues and jazz records is well known, and he’s done some cover art for blues releases. He’s also written comics focusing on blues history, perhaps the most lauded of which is “Patton” from 1984, a 12-page illustrated biography of legendary delta bluesman Charlie Patton.

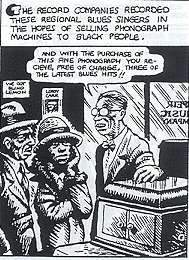

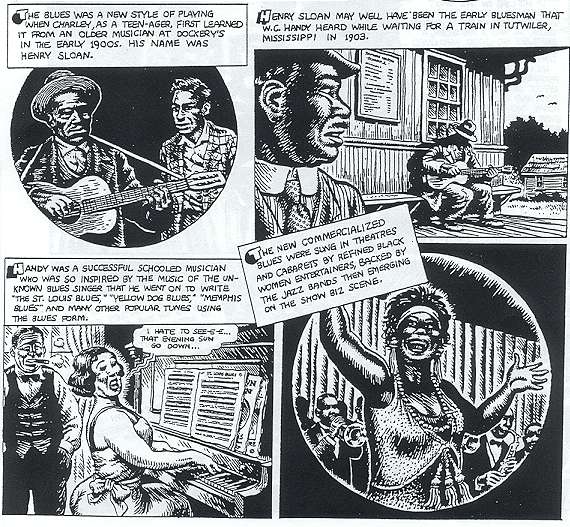

“Patton” absolutely eschews blackface caricature. Indeed, it more or less eschews cartooning, opting instead for a more realist style which seems to draw from photo-reference for its portraits of Patton, Son House, Robert Johnson, and others. Walk-on characters, though, are also portrayed as individuals. A black man and woman contemplating buying a phonograph, for example, are humorous not because they’re exaggerated, but because they aren’t; their faces are fixed in ambivalent desire and nervousness as they try to determine whether this, right here, is going to break the bank.

At the same time — it wouldn’t be quite right to say that Crumb dispenses with caricature. He just uses it more subtly. Some of his drawings of women in the strip are impossibly mobile, curving rubberlike to accentuate the more interesting bits:

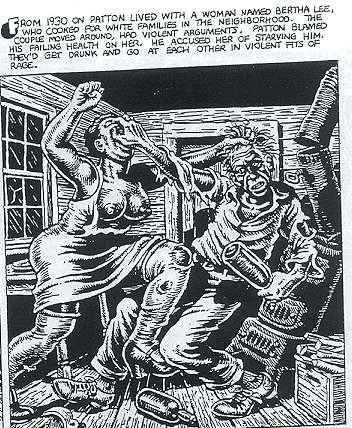

Crumb’s fascination with the female form is no particular surprise given his oeuvre. Here, though, it’s subsumed within a grander project of fetishization aimed at Patton himself. Crumb’s recounting of the bluesman’s life is matter-of-fact, but there’s little doubt that not just Patton’s musical genius but his shiftless, earthy, sex-and-violence drenched life is a huge source of attraction for the cartoonist. You can see it in the enthusiasm with which Crumb’s pen limns the posterior in that picture above, as well as in the gratuitously R-rated fight scene below:

But I think Crumb’s fascination also comes out in subtler moments. There’s this passage for instance:

“The tin-pan alley blues barely touched the remote rural black people of the Delta region, where the real down-to-earth blues continued to evolve as an intense and eloquent expression of their lives.”

That statement may or may not be entirely true (the back and forth between rural and urban was arguably not quite as hard and fast as Crumb makes it out to be.) But the important point is that Crumb is making a distinction between Ma Rainey and Charlie Patton — and Patton is the one who is intense, who is eloquent, and who is “real”. In his appreciation of the form, then, Crumb has bypassed not only Janis Joplin but even Sarah Vaughn and her compatriots to arrive, at last, at the genuinely authentic expression of the blues.

In “Patton”, appreciation is not passive contemplation; it’s more like passion or desire. Crumb, for example, shows two consecutive panels of men appreciating the playing of seminal bluesman Henry Sloan. First Charley Patton looks at Sloan with an intense, almost needy fascination; then W. C. Handy looks at Sloan with a glance that holds more surprise, but no less yearning.

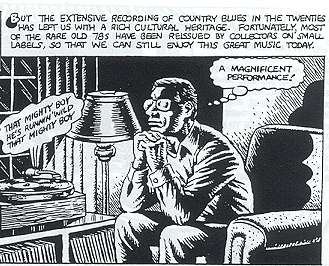

These meaningful stares are complemented a couple of pages later by this panel:

This doesn’t seem to quite be Crumb — his self-caricatures are generally instantly recognizable. But, at the same time, it clearly is Crumb; the white connoisseur who appreciates the “rich cultural heritage” of those African-Americans who (according to Crumb in the next panel) see the “old blues” as “too vivid a reminder…of an oppressive ‘Uncle Tom’ past they’d rather forget about.” Only the white listener can appreciate the lower-class, un-PC genius of the blues, undistracted by a history of oppression which regrettably (if understandably) blinds the music’s most direct heirs.

Of course, as we’ve seen, Crumb himself is responsible for at least one of the most widely disseminated modern examples of vicious Uncle Tom iconography in existence. Given that, it seems fair to wonder whether he isn’t protesting a bit too much here. Are black folks really disdainful of the blues because the music is not as uplifting as gangsta rap? Do they really see blues songs about violence, sex, and drinking as somehow Uncle Tomish? Or, you know, is the music just really old pop culture, and therefore not of particular interest to most people, as is generally the case with very old pop culture?

Perhaps the real question is not why black people don’t love the blues enough, but why Crumb loves it so much. After all, what is he getting from this story of authentic black people carousing and fighting and making great timeless art which only he and a select few like him understand?

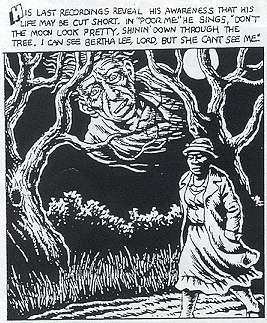

It’s not really that difficult a question, obviously. White American culture (and not just American), from Gershwin to Joplin to Vanilla Ice and Madonna (to say nothing of Elvis) has long been obsessed with adopting, miming, parodying, and exploiting black culture. Because they have been oppressed and marginalized, blacks have taken on a kind of totemic value; they and their culture are the ultimate expression of resistance to the man, of purity and heart in the face of a monolithic culture of indifference. Being black is being cool — and through his love of old blues, Crumb can be blacker than Janis Joplin, blacker than Bessie Smith, blacker than non-blues-listening African-Americans — blacker, in other words, than black. On the last page of the story, we see a ghostly Charlie Patton floating above his girlfriend Bertha Lee — and you have to wonder if that’s how Crumb sees himself, an intangible, unseen observer, both watching and inhabiting the long-dead African-Americans he animates and desires. We haven’t, after all, come that far from Cheap Thrills; it’s just that, instead of drawing blackface, Crumb has — circuitously and with less painful racist connotations, but nonetheless — donned it himself.

____________

Karen Green had a thoughtful comment at Comixology.

In fairness, Noah, the two gratuitously naked and/or nubile women you show in the Patton comic would likely have been gratuitously naked and/or nubile even if they were white woman. As a woman, I’m well aware of how Crumb prefers to depict us!

There’s no excusing the Cheap Thrills cover, however.

I think you’ve touched on something quite insightful, though, in concentrating on WHY Crumb loves the blues–especially to the extent that he loves it. There is clearly the love of the arcane, the elevation of self into a particularly rarefied aficionado. (And I would wager there are just as many African-Americans pursuing that arcane love of the blues as there are whites.) But there’s also a possibility that a man who grew up seeing himself as marginalized and miserable–regardless of how easy his life was in comparison to former slaves–might find something kindred in that music.

That possible sense of kinship is what makes the Cheap Thrills cover all the more distasteful. Like Al Jolson in blackface gleefully reading the Yiddish paper The Forvert in the film “Wonder Bar,” it’s as if Crumb has embraced that black experience but still wants to prove that he exists apart from it–a particularly unpleasant wink at the audience.

And I responded:

I’d agree that it’s hard to tease Crumb’s misogyny out from his racism. My point here isn’t that he’s racist rather than misogynist, but that his fetishization of women bleeds over and inflects his fetishization of Patton. (Through his emphasis on Patton’s sexuality, through the use of significant glances sexualizing the blues, etc.) I think you could argue that it goes the other way as well, though (that is, the fetishization of blackness as earthiness inflects his misogyny.)

Art doesn’t belong to anyone; there’s absolutely nothing wrong with white people being into blues. There is, as you say, though, something unpleasant in the way Crumb seems to want to set himself up as more in tune with “authentic” blackness than some black people — especially given his really unfortunate history with racist caricature.

_________

This is a belated entry in our roundtable on R. Crumb and Race.

Er, I think there’s a fair amount of irony in that image. It’s a stiff and too idealized white intellectual. The point is about the distance between the world the music came from and the environment in which it currently circulates (like the Arcade strip which was reprinted in the Brunetti sampler). Your interpretation strikes me as very un-Crumb-like.

That is…

“This doesn’t seem to quite be Crumb — his self-caricatures are generally instantly recognizable. But, at the same time, it clearly is Crumb; the white connoisseur who appreciates the “rich cultural heritage” of those African-Americans who (according to Crumb in the next panel) see the “old blues” as “too vivid a reminder…of an oppressive ‘Uncle Tom’ past they’d rather forget about.” Only the white listener can appreciate the lower-class, un-PC genius of the blues, undistracted by a history of oppression which regrettably (if understandably) blinds the music’s most direct heirs.”

It’s definitely a comment on that distance, and there is some irony — but it’s nostalgic irony, and the pointedness (to the extent there is one) seems clearly from the text directed at the black people who don’t understand or appreciate their own heritage, not at the white person who believes he does.

I’m not sure what you mean by unCrumb-like. Authenticity, blackness, and racism are themes which run throughout Crumb’s work, it seems to me. For that matter, there’s a good bit of self-vaunting in his work — hard to avoid for such a confessional artist.

Crumb is confessional but not idealizing. I think it’s about the sterility of the milieu and the sense in which a product of all that suffering is now canned and released for a stodgy, upper-class white man who evaluates it as a performance. If Crumb had wished to communicate that only this kind of person truly appreciates it he might have drawn some nebbish in Harvey Pekar-like circumstances shedding a tear and thinking about the world of the music and how nobody understands. Notice how leading to that panel you’ve got a series of four panels in which white people in various limbs of the record industry are approaching black artists or audiences to solicit or sell the music; the listener is the end product, a triumphant aristocrat savoring the performance like a fine wine. The remark that black audiences today would find it too vivid a reminder of an oppressive past (true or not) only makes a similar point that the music was inextricably linked to those conditions.

Crumb’s very much non-idealizing. But the non-idealization itself becomes an ideal; the messy honesty becomes validating. That’s the same thing that happens with the blues; that is, its earthiness and messiness — Patton’s fights and sexuality — become a mark of authenticity.

I don’t see as much irony in that panel as you do, but even if it’s the case that Crumb is critiquing the distance from the original conditions, he’s still fetishizing those original conditions and positing himself as the one who truly understands the blues’ inextricable link to them. He may be ironically commenting on the distance, but that just reifies the authenticity and his own status as the one who understands it.

None of which changes the underlying dynamic: he’s positing himself as the one who understands the blues better than contemporary black people, which is especially unpleasant given his past flirtations with racist iconography.

Fuck does that guy know about what blacks enjoy and appreciate?

See, you ask questions like that, you’re just going to piss yourself off.

Most black people aren’t really into old blues. Most white people aren’t really into old blues. Most black and white people aren’t into Bert Williams records either. Old pop culture is old; it’s a specialist interest. You could talk about the reasons for that, but I don’t think it has anything to do with folks’ unwillingness to embrace authenticity.

I wonder if there isn’t a large contingent of middle aged black intellectuals that is deeply invested in hillbilly music.

Uh…I don’t think so. At least, the intellectuals who write liner notes etc. for old hillbilly music appear to be overwhelmingly white.

There’s certainly a lot of black intellectuals who are into old blues/jazz, though.

I was totally kidding. But I like the image of Cornel West swapping 78’s with Molefi Kete Asanti and arguing over the relative merit of banjo licks.

The thing is the blues as a form was actually arguably biracial; there were a lot of hillbilly performers who were basically blues, anyway (Jimmie Rodgers most notably.) The distinction between blues and hillbilly music was at least as much about marketing and segregation as about actual formal considerations.

“he’s still fetishizing those original conditions…”

True, although the ink-drenched, Gothic romanticism of the style is as much about their impossible distance from himself.

“He may be ironically commenting on the distance, but that just reifies the authenticity and his own status as the one who understands it… None of which changes the underlying dynamic: he’s positing himself as the one who understands the blues better than contemporary black people…”

To the extent that he identifies himself with the listener he is implicating himself- and his audience, his “we” and “us” betray an idea of that- in those class conditions. The connoisseur admiring the “magnificent performance” doesn’t “truly understand” the experience or the music, but is associated with the record industry shown approaching the musicians and with the old white woman underneath saying she had no idea; “we were never the type of plantation owners who invited their help to come and sing at parties.” There’s a “shoe on the other foot” moment in his “When the N*****s/When the God-damn Jews Take Over America.” Whether he was right or wrong in 1984 when he wrote “it seems the old blues is still too vivid a reminder to black people of an oppressive, ‘Uncle Tom’ past they’d rather forget about” the statement could as easily be taken to mean they understand it all too well.

“which is especially unpleasant given his past flirtations with racist iconography.”

I’m ambivalent about that stage of his career, but I think he’s obviously serving that stuff up as part of a stew of American demons which the liberal, well-meaning, upper-middle-class white reader would wish to cover over. Again, I think he has a very clear notion of his audience, which could have been mostly accurate but is still problematic. I think he was working without any concern or even awareness for how black people take those images and had no interest in the reaction of openly racist white people. He was myopically poking his demographic.

Well, I don’t know that we actually disagree that much. I would say maybe that his myopic focus on his demographic continues in this particular piece — and that part of that myopia, here and earlier, is a desire to escape that demographic for something which he sees as more authentic.

“The distinction between blues and hillbilly music was at least as much about marketing and segregation as about actual formal considerations.”

Agreed, but where popular music is concerned formal considerations almost always take a back seat to marketing (and segregation when and where applicable) to the point where I’m not even sure how you’d begin to separate the two. This is why the “punk rock” appellation was so problematic on the TCJ thread.

I suppose I should note that Crumb seems invested in hillbilly music as well (at least based on interviews I’ve read).

The analogy was really just an attempt to underscore the ways race continues to be a yardstick for taste. Or how political aesthetics can be.

Well, marketing is always really important when talking about genre in any context…which is why punk rock is a reasonable way to think about genre in comics, I think.

The thing about hillbilly and blues is that the marketing strongly affected the formal characteristics of genre historically; segregation has made black and white music really different in the U.S. over time, though they started form similar roots. Again, that’s generalizable to some degree, which is why it makes sense to say that the demographic limitations of comics’ audience have some limitations on its formal interests and possibilities.

—————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Are black folks really disdainful of the blues because the music is not as uplifting as gangsta rap? Do they really see blues songs about violence, sex, and drinking as somehow Uncle Tomish?

—————————–

Well, rap is “positive” in that it’s bragging about how tough/rich/oversexed you are. The blues is mournful, defeated.

—————————–

Or, you know, is the music just really old pop culture, and therefore not of particular interest to most people, as is generally the case with very old pop culture?

—————————–

Yes. As shown in his “Where Has it Gone…” story, where a very “ethnic” looking South American kid, envied by his peers, parades through the village with Menudo blaring from his boom-box, a culture can lose appreciation for the riches in their past; go for whatever is glitzy and new, even if it’s shallow crap.

——————————-

Perhaps the real question is not why black people don’t love the blues enough, but why Crumb loves it so much. After all, what is he getting from this story of authentic black people carousing and fighting and making great timeless art which only he and a select few like him understand?

It’s not really that difficult a question, obviously. White American culture (and not just American), from Gershwin to Joplin to Vanilla Ice and Madonna (to say nothing of Elvis) has long been obsessed with adopting, miming, parodying, and exploiting black culture. Because they have been oppressed and marginalized, blacks have taken on a kind of totemic value; they and their culture are the ultimate expression of resistance to the man, of purity and heart in the face of a monolithic culture of indifference…

——————————–

To some degree, yes. In the 60s — when Crumb first became famous — American Indians were likewise idolized .

But, what about the possibility that much of that appreciation was due to the fact of the music being good?

——————————–

Being black is being cool — and through his love of old blues, Crumb can be blacker than Janis Joplin, blacker than Bessie Smith, blacker than non-blues-listening African-Americans — blacker, in other words, than black.

———————————-

How “viciously racist” can you get! And howcum Crumb then only appreciates a proportionately tiny, historic part of black culture? If he wants to be “blacker than black,” why isn’t he wearing falling-town pants, gaudy “bling,” praising Rap to the skies?

———————————-

Karen Green says:

…it’s as if Crumb has embraced that black experience but still wants to prove that he exists apart from it–a particularly unpleasant wink at the audience.

———————————–

…And if he’d somehow depicted himself as part of the “black experience” (which there’s only one of, apparently; just like all Anglo males have the world handed to them on a silver platter), then he’d have been attacked for that.

By the way, most Crumb depictions of blues musicians don’t feature violence, sexuality, torment. Could it be he simply picked some who had that in their lives to create stories about because that was more dramatic, therefore more exciting to render and read about? Finding a colorful life rather than a quietly professional one more “juicy” creative fodder?

Does the fact there are more vastly movies about cops, criminals, and military men rather than accountants, teachers, and plumbers indicate Hollywood is pushing a racist image of white men as violent, or is it that the former group’s “work” is more dramatic?

“The blues is mournful, defeated.”

No it’s not. If you actually listen to old blues, it’s not especially sad. Much of it is about drinking, carousing, and fucking, just like rap. It’s fairly upbeat as well. Blues isn’t sad music.

“Does the fact there are more vastly movies about cops, criminals, and military men rather than accountants, teachers, and plumbers indicate Hollywood is pushing a racist image of white men as violent, or is it that the former group’s “work” is more dramatic?”

There are lots of black criminals in cop dramas, Mike. And actually a fair number of Hollywood dramas about teachers. And white people just aren’t portrayed as being representative of all white people or as exemplars of an authentic whiteness. Racism is about disproportion; trying to simply flip the terms is not adequate. You actually need to think about what you’re saying.

I definitely agree that the marketing demands shape genre and that genre shapes form. But I’d also suggest that an audience brings a lot to the form based on their generic expectations. So we hear punk in part because we understand the band to be punk, even though they might sound as much like pop or metal. But that’s a small point relative the larger one about how the marketing shaped the form of those two genres. I think it is very much on target, and it suggests the stakes for comics w/r/t the forces discussed in the TCJ article/post.

————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

“The blues is mournful, defeated.”

No it’s not. If you actually listen to old blues, it’s not especially sad. Much of it is about drinking, carousing, and fucking, just like rap. It’s fairly upbeat as well. Blues isn’t sad music.

—————————

Um, OK; sure doesn’t sound like appropriate labeling, then. Does “having the blues” mean being cheery, then?

Top 10 Most Depressing Blues Songs”: http://thatguywiththeglasses.com/component/content/article/54/4116

——————————-

“Does the fact there are more vastly movies about cops, criminals, and military men rather than accountants, teachers, and plumbers indicate Hollywood is pushing a racist image of white men as violent, or is it that the former group’s “work” is more dramatic?”

There are lots of black criminals in cop dramas, Mike.

——————————-

I meant movies about white guys filling those spots. (Hopefully some got the idea.)

——————————

And actually a fair number of Hollywood dramas about teachers.

——————————

Sure; but aren’t there — as I said — VASTLY MORE movies about white guys involved in violent occupations?

——————————–

And white people just aren’t portrayed as being representative of all white people or as exemplars of an authentic whiteness. Racism is about disproportion; trying to simply flip the terms is not adequate. You actually need to think about what you’re saying.

——————————–

Do my link- and reference-laden mega-posts come across as just thoughtlessly blurted out? If I don’t come to the same “approved” conclusions, apparently so.

——————————-

Being black is being cool — and through his love of old blues, Crumb can be blacker than Janis Joplin, blacker than Bessie Smith, blacker than non-blues-listening African-Americans — blacker, in other words, than black.

——————————

After my previous post, I recalled how after living in France lo these many years, R. Crumb got very into old-time French country music! So does that mean Crumb now wants to be an old French “country guy”?

Looking for further info, found this bit from the R. Crumb: Conversations book — pages 210-212 — with his own thoughts on why he finds that music so appealing:

http://tinyurl.com/7k83yb2

…And another interview, where he mentions how:

—————————

In the modern world with its pervasive mass media, the first music most of us become aware of, aside perhaps from nursery songs, is mass-produced popular music. I remember as a kid in the late 1940s — early ‘50s hearing the popular music of the time coming from radios. I recall that it had a mildly depressing affect on me… Perry Como, Rosemary Clooney, Vaughn Monroe, Frankie Lane, Patti Page, Theresa Brewer. There was something unspeakably awful and dreary about this pop music of the time. In general I have had a loathing for popular music all my life, except for the period of early rock and roll; 1955-1966. I liked some of that music, and still do. I really lost interest after about 1970.

…At first my main interest was the old dance orchestras and jazz bands that sounded like the music in old movies and Hal Roach comedies, but then I started listening to old blues 78s that I found. They sounded strange and exotic to me at first, but I grew to love this music — blues of the 1920s — early ‘30s. Then I discovered old-time country music. Again, at first it sounded crude, rough, but this music, too, I grew to love. From there I went on to find that old Ukrainian and Polish polka bands of this same period — 1920s – early ‘30s — were also great, and then I found old Irish records — wonderful stuff — Greek records, Mexican, Caribbean, on and on. Over here, living in Europe, I found great old French music, Arab/North African music, sub-Saharan, black African music, Armenian and Turkish music, even Hindu Indian music, on the old pre WW II 78s. So now, you can imagine, I have a pretty big collection of these old discs — 6,500 of them, more or less, an embarrassment of musical riches…

——————————-

http://blogs.epicindia.com/leapinthedark/2011/10/interview_robert_crumb_illustr.html

Heavens! So Crumb now wants — as a typical white racist exploiter of other cultures — to be more Greek than Greeks, more Mexican than Mexicans, more Caribbean…

or maybe he just really likes something about that music?

I wasn’t talking about whether he likes or dislikes the music. I was looking at the comic he’d made in which he talks about why he likes the music, and paying attention to what he said and how he said it.

We disagree because you insist he is congratulating himself with that image and that he loves old blues in order to don a black identity. The glasses and button-down quality of the listener, the formal language, the room all make him the essence of a white upper-middle-class intellectual. Crumb says shortly after that if Patton were alive today he would consider the preponderance of attention from such aficionados “bitterly ironic.”

“Perhaps the real question is not why black people don’t love the blues enough, but why Crumb loves it so much. After all, what is he getting from this story of authentic black people carousing and fighting and making great timeless art which only he and a select few like him understand?… Being black is being cool — and through his love of old blues, Crumb can be blacker than, etc.”

Even if that were the case, everything about that image speaks of a lack of ability to do so. One can be obsessed with authenticity and painfully aware of the gap between oneself and that authenticity; in fact, that’s a common feature of art about the subject.

Thank you, Noah, for pointing out the fact that there is plenty of upbeat blues music (obvious to anyone who has listened to very much of it).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZtPmSoi2WXE

I would add that there is plenty of depressing rap music too. Neither genre has just one emotional mode.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t1vBpbr2JL4

“Does ‘having the blues’ mean being cheery, then?”

Some words have more than one meaning. Blues can refer to:

a type of chord progression,

a genre of music,

an unhappy state of affairs,

a range of colors.

He’s congratulating himself with that image — *and with the entire piece*. Even if you’re certain that the aficianado is entirely scorned by Crumb (which I think is reaching) — *it’s still Crumb doing the scorning*. The whole piece is about how he understands old blues in ways that even contemporary black people don’t. If he’s sneering at other aficianados, that’s *him* sneering at them.

Crumb is obviously aware of the distance between the listener and the material, but that image is not entirely satirical. At the very least, the listener in Crumb’s view is correct; it is a “masterful performance”, and the listener understands that despite the fact that the culture as a whole, and black people in particular, do not. To that extent the listener is like Crumb — one who knows.

The fact that Crumb sees a distance between himself and the black performers is *not* evidence that he does not see them as authentic. It’s evidence that he does. If there were not that distance, the excitement of embracing their authenticity wouldn’t exist.

In general, and unlike many, I simply do not believe that Crumb’s irony gets him off the hook for his dicey and often frankly stupid positions in his comics. He’s fetishizing black people here. The fact that he’s self-aware to some extent that he’s fetishizing black people doesn’t change the fact that he’s fetishizing black people, any more than his self-caricatures of weak men who idolize strong women changes the misogyny of his fetishization of strong women. Irony that distances you from your unpleasant aesthetic stances without actually changing those stances just doesn’t impress me all that much. It seems like trying to have your fetish and disavow it too.

Oh, and thanks for the point about hip hop having a wide emotional range, Matt.

————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

I wasn’t talking about whether he likes or dislikes the music.

————————–

To add to scott rouleau’s rejoinder, you — and kindred spirits such as Karen Green — were making the argument that the reason Crumb was so into the blues was not that he found it aesthetically appealing, but out of some racist, vampiric, colonialist attempt to absorb the perceived “authenticity” out of it. That Crumb was trying to “suck the coolness” out of it:

————————–

Because they have been oppressed and marginalized, blacks have taken on a kind of totemic value; they and their culture are the ultimate expression of resistance to the man, of purity and heart in the face of a monolithic culture of indifference. Being black is being cool — and through his love of old blues, Crumb can be blacker than Janis Joplin, blacker than Bessie Smith, blacker than non-blues-listening African-Americans — blacker, in other words, than black.

—————————

If Crumb is supposedly so obsessed with ‘being cool,” why is it that he not only dresses and acts like, but depicts himself as a hopelessly nerdly, uncool, neurotic misfit?

—————————

…Only the white listener can appreciate the lower-class, un-PC genius of the blues, undistracted by a history of oppression which regrettably (if understandably) blinds the music’s most direct heirs.

—————————

Yet as you perceptively noted a few lines earlier:

—————————

In “Patton”, appreciation is not passive contemplation; it’s more like passion or desire. Crumb, for example, shows two consecutive panels of men appreciating the playing of seminal bluesman Henry Sloan. First Charley Patton looks at Sloan with an intense, almost needy fascination; then W. C. Handy looks at Sloan with a glance that holds more surprise, but no less yearning.

—————————

“Only the white listener”? If supposedly championing the superior taste of “Whiteman,” howcum then Crumb showed blacks like Patton and Handy even more enraptured at hearing that music? (And lots of appreciative black audiences at the time delightedly dancing to it.)

My mention of “Whiteman” hopefully reminding how Crumb frequently jabs at the repressed, button-down culture of his formative years; with characters named Whiteman or Flakey Foont attracted/repelled by that which is raw, down-to-earth. Most explicitly expressed in his lengthy “Whiteman Meets Bigfoot” story: http://rcrumb.blogspot.com/2012/01/whiteman-meets-bigfoot.html .

Though Crumb’s rejection of pinky-in-the-air refinement in arts and a culture is hardly a racial thing; for instance, he’ll prefer Brueghel’s paintings of carousing peasants to, say, Fragonard’s frothy aristocrats-at-play.

Would not the relative indifference of blacks these days to that music (let’s not forget that among whites, the nlues are hardly a mainstream taste either) then be an accident of history, of changing cultural tastes, rather than indicating them to be inferior in their tastes?

For that matter, while Native American languages ( http://www.ahalenia.com/noksi/tsalagi.html ), music ( http://www.phnompenhpost.com/index.php/2012012054072/Lifestyle/rescuing-the-classics-saving-traditional-music-from-extinction.html ) and folktales are going extinct and being forgotten , little-appreciated by the young of those groups, most of whom are eager to be absorbed into “modern,” mainstream culture, it’s anthropologists and linguists — in this country, overwhelmingly white — who are going about making recordings, trying to save them from being utterly lost.

(No doubt some will condemn these academics as just white colonialist racists, trying to steal the “authenticity” from these people…)

And as Crumb shows in Patton, in the subject’s time not only where whites uninterested in the blues, but “respectable, church-going blacks” looked down upon that music: http://www.celticguitarmusic.com/patton4.htm .

————————–

Crumb’s…fetishizing black people here. The fact that he’s self-aware to some extent that he’s fetishizing black people doesn’t change the fact that he’s fetishizing black people…

————————–

The whole story may be read at http://www.celticguitarmusic.com/patton1.htm . Where instead of a wholesale “fetishizing [of] black people,” we see a huge range of African-Americans depicted. Uptight churchgoers, middle-class types, impoverished sharecroppers, “refined black women entertainers,” strict fathers, tough cops, self-satisfied older musicians “disdaining young [Robert] Johnson’s faltering efforts on the guitar.”

If Crumb “fetishized” each and every single one of these groups he depicts, then it would be accurate to say (three times!) that “he’s fetishizing black people.” Yet, clearly he’s not; so the continued attempt to smear him as a racist is based on a distorted view of the actual story.

Indeed, though Patton is the subject of the story, it’s not as if Crumb puts down black blues-players who do not pursue a similarly tragic, self-destructive pattern. There are plenty given respect to who are hard-working, professional in their dedication.

—————————

I was looking at the comic he’d made in which he talks about why he likes the music, and paying attention to what he said and how he said it.

————————–

And, thanks to viewing it through ideological spectacles, interpreting to fit your worldview.

Just as a fervent feminist would see a man holding open a door for her not as courtesy (which might as easily be extended to males as well), or an old-fashioned bit of chivalry, but a “vicious,” condescending insult; an attack implying that she’s considered incapable of opening a door for herself.

Or a right-winger will hear someone criticizing the war on Iraq, abuse of prisoners in Guantanamo, and think this is an “America hater,” a “friend of terrorists.”

—————————-

Matt H says:

“Does ‘having the blues’ mean being cheery, then?”

Some words have more than one meaning. Blues can refer to:

a type of chord progression,

a genre of music,

an unhappy state of affairs,

a range of colors.

——————————

Sure; yet that the musical “blues” is associated with the emotional “blues” is no coincidence. The first piece following is hardly scholarly, but has some interesting info:

——————————-

Where did blues get its name ‘the blues’?

…So far, this is what I’ve found: Not only did I read this on the internet, but I saw an old African American woman from south Mississippi explaining the same thing on a documentary. She said that back in those days they would say that there were spirits they called the blue devils that could make bad things happen or make people unhappy. When someone was down and out or sad or upset, they would say : “Oooo, he got a case of the blue devils,” or “the blue devils must’ve got a hold of him!” In reading on the internet, I found that in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s when people were coming to America from England, some people believed that there were “low” spirits that came over on the boats with the people from England. These spirits were believed to be able to cause problems for people and make them feel bad. Washington Irving in 1807 wrote of a man “under the influence of a whole legion of the blues,” and a young U. S. Grant wrote in 1846, “I came back to my tent and to drive away the Blues, I took up (read) some of your old letters.” So over time, people began to use the term “blues” or “blue devils” to explain or describe the same thing that we still call “having the blues” today. African Americans put their blues to music, singing songs about oppresion, sadness, lost loved ones, etc…

Also, a main characteristic of blues music is the use of the ‘blue notes’, which is a flattening of the 3rd, 7th and 5th scale degrees…

——————————

http://wiki.answers.com/Q/Where_did_blues_get_its_name_%27the_blues%27#ixzz1kHpDB5TR

——————————

The most important American antecedent of the blues was the spiritual, a form of religious song with its roots in the camp meetings of the Great Awakening of the early 19th century. Spirituals were a passionate song form, that “convey(ed) to listeners the same feeling of rootlessness and misery” as the blues. Spirituals, however, were less specifically concerning the performer, instead about the general loneliness of mankind, and were more figurative than direct in their lyrics. Despite these differences, the two forms are similar enough that they can not be easily separated — many spirituals would probably have been called blues had that word been in wide use at the time…

…The first appearance of the blues is not well defined and is often dated between 1870 and 1900, a period that coincides with the emancipation of the slaves and the transition from slavery to sharecropping and small-scale agricultural production in the southern United States.

Several scholars characterize the early 1900s development of blues music as a move from group performances to a more individualized style. They argue that the development of the blues is associated with the newly acquired freedom of the slaves. According to Lawrence Levine, “there was a direct relationship between the national ideological emphasis upon the individual, the popularity of Booker T. Washington’s teachings, and the rise of the blues.”

——————————-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Origins_of_the_blues

Hm! So, while spirituals were expressions of communal suffering (and hopes for a better life), the blues indicate how emancipation atomized the group. The emphasis now on lonely, individual suffering and travails…

Right; thankfully you have no ideological spectacles, and are perceiving the thing in its pure objective suchness.

“If Crumb is supposedly so obsessed with ‘being cool,” why is it that he not only dresses and acts like, but depicts himself as a hopelessly nerdly, uncool, neurotic misfit?”

Crumb’s whole schtick is his opposition to bourgeois middle-class white culture. His self-presentation as a nerdy outsider fits perfectly with that stance.

—————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Right; thankfully you have no ideological spectacles…

—————————–

As proof of such, the fact that my arguments and attitudes, rather than following a rigid “party line,” range all over the place. I’m a feminist* who criticizes the movement when some of its arguments are idiotic, unrealistic; blast both Bush and Obama when they uphold vile policies; am for altering the impoverishment which is significant factor in creating criminals (liberal!), but for strong punishment of violent criminals (conservative!).

And rather than ignoring/snipping away complexities and details which would weaken the simplistic “R. Crumb drew some big-lipped ‘coon’ types, therefore he’s a racist” argument — the epitome of “ideological spectacles” in action — I point out that there is much in Crumb which does not fit the Procrustean bed in which others seek to distort his work.

——————————

Crumb’s whole schtick is his opposition to bourgeois middle-class white culture. His self-presentation as a nerdy outsider fits perfectly with that stance.

——————————

Oh? And in what way does that fit in with his being “blacker than Janis Joplin, blacker than Bessie Smith, blacker than non-blues-listening African-Americans — blacker, in other words, than black”?

Or does it not — like his depiction of the cerebral-looking, bespectacled white aficionado of the blues, thoughtfully seated in his armchair, contrasted with the lively black crowds dancing to Patton’s music — merely emphasize the gulf between the appreciation of the music in the two groups?

—————————–

There is…something unpleasant in the way Crumb seems to want to set himself up as more in tune with “authentic” blackness than some black people…

—————————–

Where in his interviews or comics story does Crumb indicate he thinks that Patton or the blues represent ” ‘authentic’ blackness”? In Patton one sees a whole range of African-Americans, none indicated as more “authentic” than others. Even among the blues musicians, a whole array of approaches and personalities are indicated.

As usual, we get the “accuse somebody of making an outrageous statement they never made, then attack them for making an outrageous statement” bit.

When Crumb writes, “The tin-pan alley blues barely touched the remote rural black people of the Delta region, where the real down-to-earth blues continued to evolve as an intense and eloquent expression of their lives,” is that not a valid comparison between a more original, “close to the source” outpouring of creativity and “The new commercialized blues [which] were sung in theatres and cabarets by refined black women entertainers, backed by…jazz bands”?

Is pointing out that cultural traditions can be colonized, homogenized, made slick to appeal to a broader audience therefore an argument that “authentic blackness” is being adulterated, or rather the less-inflammatory one that a specific variety of black music is being so treated? (In many cases, by black musicians themselves, eager for “crossover hits.”)

*Oh, but as some will argue, a man can’t be a REAL feminist; the only thing males can do is bow their heads in shame for all their oppressiveness and privilege, and not challenge even the most asinine arguments made by any woman. (Which is, of course, not an “ideological spectacles” way of viewing things at all.)

Oh, bullshit. You’ve got your prejudices just like anyone else.

And, no, it’s not true to say that jazz is less close to the source, whatever that means, than blues is. Jazz was urban music, but why is urban less authentic than rural exactly? What soruce are we even talking about? Jazz was an extremely original art form created not entirely but predominantly by black people. Why is Louis Armstrong less “real” than Charlie Patton? Why is Ma Rainey? What does that even mean? You’re just reinscribing Crumb’s fairly dunderheaded notions of authenticity, not providing an argument (such an argument being unprovidable since it’s just nonsense anyway.)

For that matter, Charlie Patton has several songs influenced by hillbilly music. And lots of country blues performers were influenced by jazz and ragtime.

You’ve never listened to any of this music, have you, Mike? How can you even assess what is an outrageous statement and what isn’t when you have no idea what you’re talking about?

And speaking of setting up straw men, I never said R. Crumb was a racist. I don’t know what’s in his heart. Instead, I said drawing racist images is a racist thing to do. I said that his fetishization of authenticity is also, less flagrantly, but still, racist, and that it fits painfully with his earlier use of racist iconography.

And incidentally, I pointed out that he draws different kinds of black people in the story. For someone without ideological blinders of any sort, you’re spending an awful lot of time arguing against things that you expect me to have said, but which I did not in fact say.

I mean, does it help to know that Ma Rainey had a reputation for fighting too, and for sexual exploits (with both men and women)? Can she be authentic now? Should we write Crumb and ask him how much fucking and fighting one needs to undertake in order to get his stamp of approval?

It really pisses me off, frankly, to have Crumb proclaiming on which poor black musical genius is or is not up to his exacting standards of realness. Can’t you see why that is both presumptuous and offensive? If he prefers old blues to old jazz that’s cool, but making it a matter of who is “closer to the source” is asinine, and he should be mocked for it.

I think it’s fair to say that Crumb’s work is racist…even that he’s racist. Truth to tell, the vast majority of us in America (and really, in many other places), if not all of us, are racist to some degree. We live in a historically racist society and it’s pretty hard to get out from under that. Many of us try–including, perhaps, Crumb himself–with varying degrees of success. You don’t need to “know what’s in his heart” to see that, in his work, he’s admitting his own, and his society’s racism, even if he, at times, also critiques and combats it.

Crumb is into old-timey white music too, though, so if he’s fetishizing “authenticity” in music and culture (which I think he certainly is), that authenticity is not only defined by blackness and is, at times, separable from it. It is also true that “blackness” is a substitute for authenticity in American culture (thus, “keeping it real”)—and it is no surprise that Crumb’s fixation with one becomes (or overlaps) his fixation with the other.

I don’t know if it’s all about fucking and fighting, as he loves traditional French and Hawaiian music and other folksy stuff that isn’t wrapped up with poverty or being a bad-ass. Crumb is really into the idea that art can only be great if it comes from a personal need and that it’s ruined by concerns about mass commercial appeal or respectability. It’s a very socialist take on culture, when you think about it. Even though I love tons of pop-culture stuff, I think he probably has a point there.

On the jazz vs. blues front–in his 80s-era letter exchange with R. Fiore, he laid out a theory about how culture is at its best when it’s connected to the earth, meaning that urban music will never be as good as rural music.

His enthusiasm for Patton seems very tied to his enthusiasm for Patton’s persona. That doesn’t mean that everything he likes will be connected to Patton’s persona. But it does suggest, since he also likes Patton’s realness, that the realness and the persona go together. He can find other reasons to like the realness of other music, I”m sure, but Patton’s violence and sexuality is absolutely a reason he likes Patton’s realness.

“he laid out a theory about how culture is at its best when it’s connected to the earth, meaning that urban music will never be as good as rural music.”

Right. And he is completely full of shit. His authenticity mongering leads him to pronounce on the authenticity and realness of others and to tell them which parts of their culture are real. Which is offensive crap, and he should be called on it, and, indeed, mocked for it.

Among other things, early blues, including that by Charlie Patton, was a commercial music. If it wasn’t a commercial music, how would Crumb know about it? Those discs weren’t made by magic; they were made because there was a commercial audience. Patton made various kinds of music, from spirituals to “blues” (which was a marketing category to begin with) to hillbilly music, presumably at the behest in part of marketing folks who were trying to figure out what might be a hit.

None of which is to say that Patton’s music was compromised, or that it’s worse because it’s not “pure.” He was a great musician; I like his music. But my liking him doesn’t give me some insight into the souls of black people or the volk which those who like Ma Rainey can never approach.

A fascination with volk culture and authenticity isn’t just socialist, incidentally. It’s also national socialist.

Yeah; I’m not saying he thinks the only authenticity is blackness. But one form of authenticity for him is blackness, and he claims to know more about it than people who are actually black. Which is unpleasant, it seems to me.

Well, I think he’s into 20s and 30s music because it straddled the line between folk culture and mass culture, with people selling music that wasn’t too far removed from what their grandparents played. Of course, I don’t know enough about it to say much more without making a complete ass of myself.

Do you think there’s anything at all to the idea that authenticity in art is good while inauthenticity is bad? Does it make any sense at all to smirk at Mick Jagger for being a middle-class Brit trying to sound like a sharecropper?

The thing about Mick Jagger’s posturing that is problematic is the way he presents blackness as tough/sexually potent, and then tries to become tough and sexual by aping blackness. He’s doing the exact same thing Crumb is, and sure, I don’t mind mocking him for it.

But the issue is the presentation of authenticity, not that he’s failed to be authentic. There are lots of great musicians who are not black, not rural, and unabashedly commercial — the Rolling Stones among them.

“Well, I think he’s into 20s and 30s music because it straddled the line between folk culture and mass culture, with people selling music that wasn’t too far removed from what their grandparents played.”

Yeah, but…the music their grandparents played was commercial too.

It probably was fairly far removed from it as well; there’s musical change and cross-breeding in societies that don’t have recording technology. It’s just harder to document.

Nice reply to this post here.

eric b- “I think it’s fair to say that Crumb’s work is racist…even that he’s racist. Truth to tell, the vast majority of us in America (and really, in many other places), if not all of us, are racist to some degree. We live in a historically racist society and it’s pretty hard to get out from under that. Many of us try–including, perhaps, Crumb himself–with varying degrees of success. You don’t need to “know what’s in his heart” to see that, in his work, he’s admitting his own, and his society’s racism, even if he, at times, also critiques and combats it.”

That’s just it. We’re not social atoms. We’re all implicated. Any artist addressing these subjects must deal with his or her complicity. But an artist who doesn’t place all his opinions on the surface will be vulnerable to Noah’s “Gotcha! Racist!” approach.

Noah- “He’s congratulating himself with that image — *and with the entire piece*. Even if you’re certain that the aficianado is entirely scorned by Crumb (which I think is reaching) — *it’s still Crumb doing the scorning*. The whole piece is about how he understands old blues in ways that even contemporary black people don’t. If he’s sneering at other aficianados, that’s *him* sneering at them.”

No, he’s not isolating himself from the white listener, he says “we” and “us.” His drawing epitomizes the listener’s position in class and cultural processes; “we, the connoisseurs.” Describing that outcome as “bitterly ironic,” and ending with Patton on his deathbed looking forward to an otherworldly consummation, casts the whole package in a negative light. Beyond that, the “self-congratulation” you resort to pointing out would apply to anyone expressing an opinion.

“His authenticity mongering leads him to pronounce on the authenticity and realness of others and to tell them which parts of their culture are real. Which is offensive crap, and he should be called on it, and, indeed, mocked for it.”

Crumb prefers a specific kind of cultural expression. As other commenters are pointing out, it extends beyond black culture. He’s been consistent enough that I think we can give him credit for meaning it. His vision might be simplistic and romantic, but it’s a social vision which extends past himself, nor does he relate it to himself consistently enough and in ways that would justify your collegiate assessment of it as a quest for a “cool” identity. For example, do you find his “A Short History of America” strip sincere?

Can a person appreciate art, which goes hand in hand with preferring certain kinds and rejecting others, by people who are not like him? Can he have an interest in a world outside his experience without being a fraud and an impersonator?

There’s no reason someone can’t appreciate all kinds of art, or have an interest in the world outside his experience. However, as an artist, Crumb is responsible for what he says and for the kind of representation of black people he chooses to make. If he’s going to go around telling black people when they are or are not authentic, I think it’s fair to say, “that’s offensive crap.” It’s not about playing gotcha. It’s about responding to what he’s saying. And what he’s saying is, “I understand this music, and you don’t.”

It wouldn’t have to be self-congratulatory, or at least not along the same lines. He could, for example, point out that pop culture of the past is in general not very popular, no matter how earthy or authentic it is — Ma Rainey doesn’t have much more of a public profile these days than Charlie Patton does. He could think about what he gets out of the music, and talk about his own history of racial caricature. He could, in other words, take responsibility for his own shit and not pass moralistic judgments on people he’s not in any position to judge. That wouldn’t be at all inconsistent with saying, “I like Charlie Patton more than Ma Rainey,” nor would it be inconsistent with having an interest in the world outside his navel. On the contrary, it would involve treating other people who didn’t look like him as if they were in fact people rather than fetish objects in his own personal psychodrama.

Alo, in terms of Patton seeing it as ironic that white people liked his music — what exactly would the irony be? I don’t think it would be, or could be, “these people aren’t authentic enough to like my music,” from his perspective. Instead, the irony would be that white people, who once discriminated against him, now liked his music, while his own people did not. It’s an irony that redounds against the black people who don’t understand him, not against the white people who now listen to him.

The whole thing is kind of stupid anyway. In general, black bluesmen who got attention later on through the folk revival (Son House, for example) saw it not as a bitter irony for the most part but as a surprisingly welcome influx of cash. I’m sure there was a certain amount of “these white people are crazy!”, and there could well be tension around white people’s (ahem) authenticity fetishes, as when John Lomax insisted that Leadbelly dress in prison togs to perform rather than in a suit. But I suspect Patton would have happily performed for a different audience if he’d lived long enough to do so. He was an entertainer, and he was in business to make money. It’s Crumb who’s hung up on the ironic distance between the pure and the impure, not Patton.

And, incidentally, it’s not about sincerity. I believe that Crumb is sincere. Desiring authenticity is a very sincere desire. But just because it’s sincere doesn’t mean that it also isn’t, in your words, “simplistic and romantic.” And when you’re talking about race, “simplistic” often ends up looking an awful lot like “racist.” For that matter, racism is sincere. Sincerity isn’t any more of an out than irony or the generalized “oh, we’re all implicated.” If you say stupid crap, it’s stupid crap, whether it’s ironized or whether you really mean it or whether you can point to other people and say, “You’re another”.

I haven’t seen a short history of america in a long time…but yeah, I think it’s simplistic and romantic, not to mention glib. Industrialization is problematic, but the rural past was no particularly great shakes either…not least because, you know, the rural past involved slavery in the U.S. Again, it reads as much more about Crumb exploring his own psych and his own issues with authenticity than as a social comment of any kind — though that just means it ends up being a stupid social comment.

Johnny Ryan’s parody is pretty great though, if you’ve ever seen that.

————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

And, no, it’s not true to say that jazz is less close to the source, whatever that means, than blues is.

—————————

From that article I linked to:

—————————

,,,No specific year can be cited as the origin of the blues, largely because the style evolved over a long period and existed in approaching its modern form before the term blues was introduced, before the style was thoroughly documented. Ethnomusicologist Gerhard Kubik traces the roots of many of the elements that were to develop into the blues back to the African continent, the “cradle of the blues”. One important early reference to something closely resembling the blues comes from 1901, when an archaeologist in Mississippi described the songs of black workers which had lyrical themes and technical elements in common with the blues.

…Many of these blues elements, such as the call-and-response format, can be traced back to the music of Africa. The use of melisma and a wavy, nasal intonation also suggests a connection between the music of West and Central Africa and the blues. The belief that blues is historically derived from the West African music including from Mali is reflected in Martin Scorsese’s often quoted characterization of Ali Farka Touré’s tradition as constituting “the DNA of the blues”…

—————————

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Origins_of_the_blues

A “The Origins of Jazz” essay at http://www.redhotjazz.com/originsarticle.html mentions how…

—————————

Many Jazz writers have pointed out that the non-Jazz elements from which Jazz was formed, the Blues, Ragtime, Brass Band Music, Hymns and Spirituals, Minstrel music and work songs were ubiquitous in the United States and known in dozens of cities. Why then, they reason, should New Orleans be singled out as the sole birthplace of Jazz?

—————————-

Since the blues was one of the “non-Jazz elements from which Jazz was formed,” therefore the blues antedated jazz. And as if that wasn’t enough to mark it as “closer to the source” (my own phrase; Crumb doesn’t use it)…

—————————–

These writers are overlooking one important factor that existed only in New Orleans, namely, the black Creole subculture.

The Creoles were free, French and Spanish speaking Blacks, originally from the West Indies, who lived first under Spanish then French rule in the Louisiana Territory. They became Americans as a result of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and Louisiana statehood in 1812…

The Creole musicians, many of whom were Conservatory trained in Paris, played at the Opera House and in chamber ensembles. Some led the best society bands in New Orleans. They prided themselves on their formal knowledge of European music, precise technique and soft delicate tone and had all of the social and cultural values that characterize the upper class…

Jelly Roll [Morton], a Creole named Ferdinand LaMenthe at birth, was one of the big movers in the early development of Jazz. He explains in great detail how a Jazz piece like Tiger Rag evolved out of European dance forms like the French quadrille, the waltz, the mazurka and the polka…

—————————

http://www.redhotjazz.com/originsarticle.html

Since African tribal music was more ancient than what Jelly Roll cited (never mind refined fare such as taught in the Paris Conservatory), again the blues is closer to primal, earlier, sources of music than jazz.

—————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Jazz was urban music, but why is urban less authentic than rural exactly?

—————————-

I didn’t say it was; just mentioned where Crumb contrasted the raw, “down-to-earth blues” to “The new commercialized blues [which] were sung in theatres and cabarets by refined black women entertainers, backed by…jazz bands.”

Even in jazz itself, we see how…

—————————

Commercially oriented or popular music-influenced forms of jazz have both long been criticized, at least since the emergence of Bop. Traditional jazz enthusiasts have dismissed Bop, the 1970s jazz fusion era [and much else] as a period of commercial debasement of the music. According to Bruce Johnson, jazz music has always had a “tension between jazz as a commercial music and an art form”…

—————————-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jazz

—————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

You’ve never listened to any of this music, have you, Mike? How can you even assess what is an outrageous statement and what isn’t when you have no idea what you’re talking about?

—————————–

Sure I have, though quite some years back. (I certainly like the blues far better than jazz.) So you’re saying that simply listening to some music somehow educates one to assess its worth, historic influences, etc.? If so, then Crumb must be vastly more knowledgeable about the blues than everyone here put together, no?

Personally, I have found seeing documentaries, reading critical writings and histories of the blues by actual experts more truly educational. Were I to simply judge by what I have listened to and appreciated more, I’d consider the B-52s better than Beethoven, the Beatles superior to Bach.

—————————–

And speaking of setting up straw men, I never said R. Crumb was a racist.

I don’t know what’s in his heart. Instead, I said drawing racist images is a racist thing to do. I said that his fetishization of authenticity is also, less flagrantly, but still, racist, and that it fits painfully with his earlier use of racist iconography.

—————————-

No, not saying he’s a racist. We just get lines like, “…it’s hard to tease Crumb’s misogyny out from his racism.” Just maintaining how every other thing he does is racist. That if he really likes one kind of music, therefore racism must be behind it: “Being black is being cool — and through his love of old blues, Crumb can be blacker than Janis Joplin, blacker than Bessie Smith, blacker than non-blues-listening African-Americans — blacker, in other words, than black.”

That by showing a white aficionado listening to a blues record, Crumb is saying “Only the white listener can appreciate the lower-class, un-PC genius of the blues…” (Emphasis added). Where does Crumb maintain that blacks are utterly unable to appreciate the blues? Even a rendering of a line from Patton’s “Poor Me” is twisted thus: “On the last page of the story, we see a ghostly Charlie Patton floating above his girlfriend Bertha Lee — and you have to wonder if that’s how Crumb sees himself, an intangible, unseen observer, both watching and inhabiting the long-dead African-Americans he animates and desires. We haven’t, after all, come that far from Cheap Thrills; it’s just that, instead of drawing blackface, Crumb has — circuitously and with less painful racist connotations, but nonetheless — donned it himself.” (Emphasis added)

Oh, this is great: “A fascination with volk culture and authenticity isn’t just socialist, incidentally. It’s also national socialist.” So if you like folk music, you’re like one of those Nazis!

—————————–

[Crumb’s] enthusiasm for Patton seems very tied to his enthusiasm for Patton’s persona.

—————————–

Oh? He certainly finds Patton’s life a more dramatic subject for a story than, say, Charles Ives (“Wealthy Insurance Executive by Day…Avant-Garde Composer at Night!”). Yet, does he glamorize Patton’s life, do the equivalent of “You go, guy!” when he shows how “When things went bad he would repent and take up the Bible,” scenes of the scrawny Patton getting beat up or slashed by bigger, tougher guys? Fearful of his demise as he sings “Oh Death”?

——————————

The thing about Mick Jagger’s posturing that is problematic is the way he presents blackness as tough/sexually potent, and then tries to become tough and sexual by aping blackness.

——————————

I actually heartily agree with you here. (That “aping” is unfortunate, though…)

See, you’re getting confused by the different meanings of blues again. Blues was one of the elements from which jazz was constructed. It was also one of the elements from which blues was constructed! Patton’s music, as I said, includes hillbilly elements and popular music elements too. Jazz and Patton’s country blues were contemporary forms. It’s like saying Muddy Waters was closer to the source than Miles Davis. It looks vaguely reasonable on the surface, but as soon as think about it, it’s clear it’s nonsense.

And why exactly do you think that African music is more primal? African music is a human undertaking with a history and technology, just like any other kind of music. It’s no more (and no less) primal than electronica.

“Yet, does he glamorize Patton’s life, do the equivalent of “You go, guy!” when he shows how “When things went bad he would repent and take up the Bible,” scenes of the scrawny Patton getting beat up or slashed by bigger, tougher guys? Fearful of his demise as he sings “Oh Death”?”

He doesn’t say you go guy, but yes, the cycle of sin and repentance is totally the stuff of made for tv movies. Being in touch with religion and fear of death don’t at all contradict glamorization. Quite the contrary.

And you brought up socialism, Mike. My point wasn’t that if you like volk culture you’re a nazi, but that being into this stuff doesn’t say anything in particular about your political stance. It can be inflected in various ways, right or left.

The aficionado character is presented as having an intellectual appreciation of the music that its original audience didn’t have. Earlier in the piece, though, it is made clear that the music is meant for dancing and partying. Alone in his room, still and subdued, our aficionado couldn’t be further from that. Therefore something is missing from his understanding of the music. It’s the old Apollonian/Dionysian dichotomy. In this story it is a white character in the Apollonian mode and black characters in the Dionysian one. I don’t know if is true of all of Crumb’s work. If it’s a trend, that’s a little “problematic.”

To displace a bit of business from another site, the comics accepted by the establishment can now be seen for what they are: indistinguishable from the establishment, reflecting the values of the establishment. That goes for the products of supposed hippie spokesmen as well as for the pap inflicted on us by the mainstream.

Mike, thanks for the etymology stuff about the blues. I hope you took my “words mean different things” sassing in the spirit is was intended.

Also, Mike, what makes you say that African tribal music is more ancient than any other music? African cultures have developed for the same amount of time that all other cultures have.

James…ouch.

What other site are you displacing from? I’d be interested to see the conversation.

Crumb’s a difficult figure to deal with, there’s no doubt. To be fair, I think a lot of the enthusiasm for his work has to be because of his amazing technical abilities probably as much as anything having to do with the content per se.

Sean’s discussion of the Crumb documentary may be relevant here.

I wish I liked Crumb more than I do. The documentary, as Sean says, makes him seem like an interesting person, and I can appreciate his drawing skills. But I’ve just never seen a comic by him I really liked. His cynicism is simplistic and obvious, and his shock the bourgeoisie stance, as James suggests, mostly seems to get off on the bourgeois excesses he is supposedly critiquing or revealing.

His work is obviously about confession and honesty and self-revelation. Those aren’t bad things in themselves, but I think, for me at least, that does have to be paired with a critical understanding. It’s not enough to say what you feel; you need to be able to put that in a context that isn’t just about you. James Baldwin does that in his essays, for example. I think Ariel Schrag does it in her comics. Crumb though; when he tries to talk about other people he ends up with dunder-headed essentialism and easy stereotypes. As a result, I don’t feel like his comics really are honest; he doesn’t understand the world well enough to be honest about himself, or about anything.

Which is really harsh. Like I said, I wish I enjoyed his work more. I sort of enjoy hating Spiegelman, but disliking Crumb is mostly just depressing.

There was a mentio of TCJ of “comics now being accepted by the establishment”…it asn’t much of a discussion, someone mentioned Neil Gaiman as an exemplar of the establishment and I agree. Crumb is capable of good drawings. I like a few of his earlier strips but it is a sentimental affection, I don’t care for the larger bulk of his comics and absolutely disliked his Bible work. But that’s just me.

His work is obviously about confession and honesty and self-revelation.

Not the better stuff, or at least the better stuff in my opinion. The mid-to-late Sixties material, which is very much the basis of his cultural reputation, isn’t confessional at all. His strongest efforts after that were the Pekar collaborations, which weren’t confessional in terms of his contributions, and the “Short History of America” piece.

Around 1970, Crumb fell under the sway of S. Clay Wilson. That’s when his work took its confessional turn, and when the misogyny and all-purpose cynicism took over. Jeet Heer once wrote that this was when Crumb became Crumb, but I think it’s when, to borrow a line from Tarantino, when Crumb climbed up his own ass. The Pekar material and the “Short History” strip are the rare occasions afterward when he climbed out and took a look around.

It’s funny. Crumb is the guy who brought Surrealist and Beat thinking to comics, but his best work is the stuff that is along the lines of Eliot’s notion that art should be an escape from personality.

————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

[Mike quote] “Yet, does [Crumb] glamorize Patton’s life, do the equivalent of “You go, guy!” when he shows how “When things went bad he would repent and take up the Bible,” scenes of the scrawny Patton getting beat up or slashed by bigger, tougher guys? Fearful of his demise as he sings “Oh Death”?”

He doesn’t say you go guy, but yes, the cycle of sin and repentance is totally the stuff of made for tv movies. Being in touch with religion and fear of death don’t at all contradict glamorization. Quite the contrary.

——————————

Sure, “the cycle of sin and repentance is totally the stuff of made for tv movies,” but…

——————————

glam·or·ize

1. to make glamorous.

2. to glorify or romanticize: an adventure film that tended to glamorize war.,/i>

——————————-

(dictionary.com again)

Take another look at how Crumb drew Patton. Does he cut a dashing, heroic figure? Does Crumb show him proudly swaggering, exulting in his musical prowess, basking in the adoration of fans, or in extremis, suffering yet beautifully so, as in David’s The Death of Marat ( http://www.wga.hu/art/d/david_j/3/301david.jpg )?

In the story ( http://www.celticguitarmusic.com/patton1.htm ), even moments of “repentance,” with Patton reading the Bible, are not depicted as uplifting; Patton is sweaty, looking terrified of hellfire. Singing “Oh Death,” he’s again sweatily fearful (as the Brits would say, “bricking it”). He dies as unglamorously as can be, a pitiful figure helpless on a bed.

——————————

And you brought up socialism, Mike. My point wasn’t that if you like volk culture you’re a nazi, but that being into this stuff doesn’t say anything in particular about your political stance. It can be inflected in various ways, right or left.

——————————-

Actually, it was Jack who wrote: “Crumb is really into the idea that art can only be great if it comes from a personal need and that it’s ruined by concerns about mass commercial appeal or respectability. It’s a very socialist take on culture, when you think about it.”

Certainly, both dictatorial extremes of left and right are suspicious of intellectuality, cosmopolitanism; have exalted the supposed virtues of the “simple, hardy, unspoiled peasant.”

Yet it’s a very significant mistake to believe that because one appreciates the art coming from a certain time or culture, that one is therefore enraptured with “the whole package.” He may not love the big city, but would Crumb delight to live amongst uneducated, backwoods folks? Hardly!

Seth and Crumb may love — as I do — the style of the 20s and 30s, but are hardly in favor of the countless odious things (frequent lynchings, for instance) and attitudes of that era. Chris Ware brilliantly evokes the advertising art graphics of that time — which he clearly, rightly admires — yet acidly peppers it with phrases in the casually accepted racism of the time; a sort of poison pill in a tasty coating.

——————————–

[Crumb] is completely full of shit. His authenticity mongering leads him to pronounce on the authenticity and realness of others and to tell them which parts of their culture are real. Which is offensive crap, and he should be called on it, and, indeed, mocked for it.

…But one form of authenticity for him is blackness, and he claims to know more about it than people who are actually black.

…If he’s going to go around telling black people when they are or are not authentic, I think it’s fair to say, “that’s offensive crap.” …And what he’s saying is, “I understand this music, and you don’t.”

———————————

Uh, Crumb isn’t “telling black people when they are or are not authentic,” he’s making that assessment about a particular type of music that, indeed, he’s more knowledgeable of and understands better than 99.9999% of the human race, black people definitely included. (Though he may well be a tyro compared to even more knowledgeable blues experts.)

And he doesn’t “claim to know more about [blackness] than people who are actually black” (which would indeed be offensive, if it were true); his aesthetic judgments are entirely about their music.

Unless that “it’s a black thing, you wouldn’t understand” nonsense supposedly extends to all their music, as well. Should we tell all those masterful Chinese classic-music players they can’t begin to properly understand it, because they’re not European?

————————————–

…[Crumb’s] work is obviously about confession and honesty and self-revelation. Those aren’t bad things in themselves, but I think, for me at least, that does have to be paired with a critical understanding. It’s not enough to say what you feel; you need to be able to put that in a context that isn’t just about you. James Baldwin does that in his essays, for example. I think Ariel Schrag does it in her comics. Crumb though; when he tries to talk about other people he ends up with dunder-headed essentialism and easy stereotypes. As a result, I don’t feel like his comics really are honest; he doesn’t understand the world well enough to be honest about himself, or about anything.

————————————–