This first appeared quite a while ago in the Chicago Reader.

_____________________

Porn is the genre fiction that dare not speak its name. When you think of genre, you tend to think of sci-fi, detective, horror, western, romance, or the like. Porn doesn’t make the list — instead, its set off in a box by itself, for special censure or (less often) praise. Yet, when you look closely, porn doesn’t really seem all that anomalous. Like other genre art, it’s broadly popular, has its own predictable tropes, and appeals primarily (though not exclusively) to one gender. Porn isn’t an absolute evil ruining our children, nor is it a liberating force releasing the power of our repressed sexuality. It’s just another marketing niche.

This isn’t meant as a sneer. On the contrary, once you stop thinking about porn as moral outrage or anthropological curiosity and start thinking of it as just another pulp genre, it’s a lot easier to see its virtues and, for that matter, to put its vices in context. Like other great genre narratives — Agatha Christie’s novels, say, or John Carpenter’s movies — good porn fulfills the most obvious expectations in surprising ways while veering vertiginously between extreme technical competence and grungy amateurism. Most of all, porn, like pulp, is studiously uninterested in good taste, which means that the best examples have an energy and an imagination hard to duplicate in more sedate forms.

There’s certainly nothing sedate about Patrick Conlon and Michael Manning’s Tranceptor comic book series. The titular (in various ways) Tranceptors are a kind of female dominatrix priesthood who ride through a post-apocalyptic landscape in carriages pulled by buxom leather-clad fetish horse-girls and/or well-hung leather-clad fetish horse boys. Our heroine (called simply Tranceptor) has inventively intimate encounters with her horse-girls (chains, water, lather, various attachments), with another Tranceptor named Ravanna, and with Hyu, the cute station sub-groom who looks decidedly underage. Most spectacularly, the Tranceptor is raped by Ravanna’s pal, a disgusting mutant-lizard thing named Sslthsss. (There is no apparent lasting physical or psychological damage — the Tranceptors are a tough bunch.)

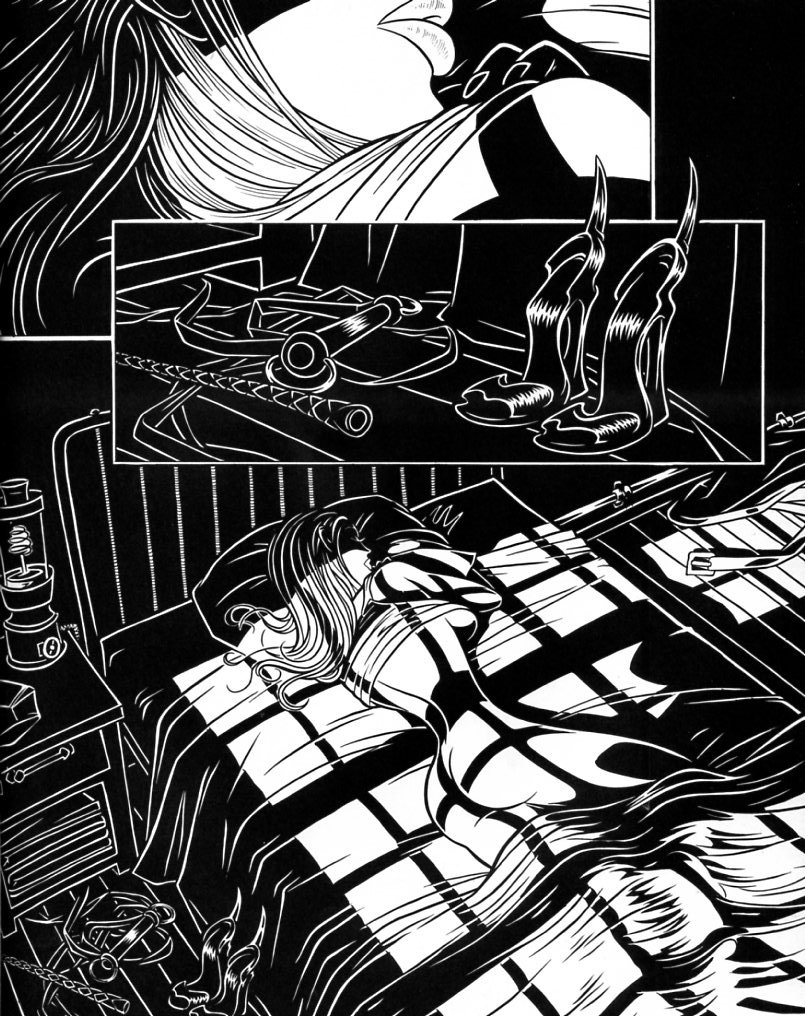

This is all trashy, stylish good fun. Conlon’s a tattoo artist, and he and Manning have that testosterone swagger down cold — the first Tranceptor volume, for example, opens with a tour de force of faux noir, sensual solid black shadows and stark whites washing over piles of fetish gear and a voluptuously writhing sleeping female form, complete with obligatory ass shots and nipple eruptions. The cynically exploitative surface flash is certainly part of the charm — but it isn’t the only thing going on, either.

Like all pulp, porn tends to cross-pollinate with other genres. The sci-fi/sex fertilization has been particularly intense. *Heavy Metal* is an obvious touchstone, but a big part of the avant-garde sf movement from the seventies on has involved explicit erotica. Writers like Samuel R. Delaney and John Varley lovingly fetishize gender transformation and interspecies intercourse — and include a fair bit of explicit sex. One paradigmatic example, Piers Anthony’s semi-masterpiece “The Barn,” features an alternate universe where some human beings are deliberately brain-damaged and then placed in barns where they are bred and milked like cattle. Our dimension-hopping protagonist gets to offer his services as stud as the story boldly explores the realm where “controversial and brave” slides right into “surreptitious stroke material.”

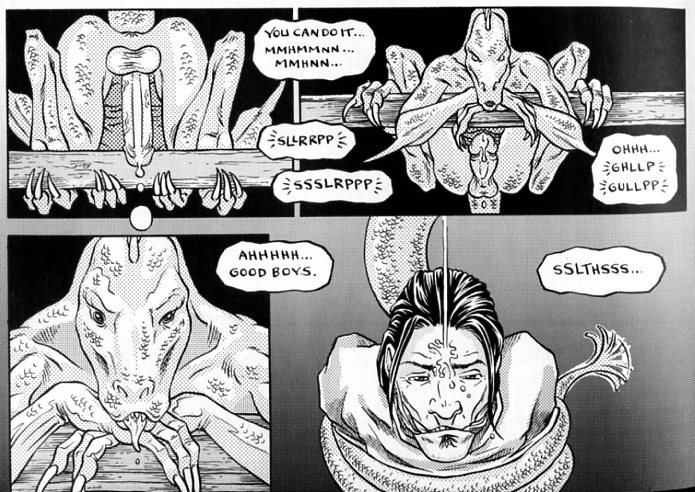

What’s especially enjoyable about Tranceptor is that, while it is in many ways heir to this tradition, it is much more comfortable with its pulp status than its highbrow predecessors. Delaney uses his forays into porn in a contradictory (but hardly unique) effort to cement his bona fides as a highbrow artist. Piers Anthony is a bit more confused — but it is certainly clear that he is conflicted about his status as pornographer. That’s not all to the bad — the intense anxiety of “The Barn” is part of what gives it its squicky charge. But there is also something to be said for being on top of your shit. Conlon and Manning’s perversion isn’t so much fraught as it is enthusiastically delectable. Probably the best image in the comic is a panel of Sslthsss, arms and legs wrapped around a structural beam, head resting on his hands, as he watches his mistress below him suck off one of her horse boys. The lizard-thing looks like a happy cat, thoroughly entertained. And to complete the picture, he’s got one of the station men named Raika tied up and dangling from his tail, and his outsized member is dripping cum on the poor guy’s head.

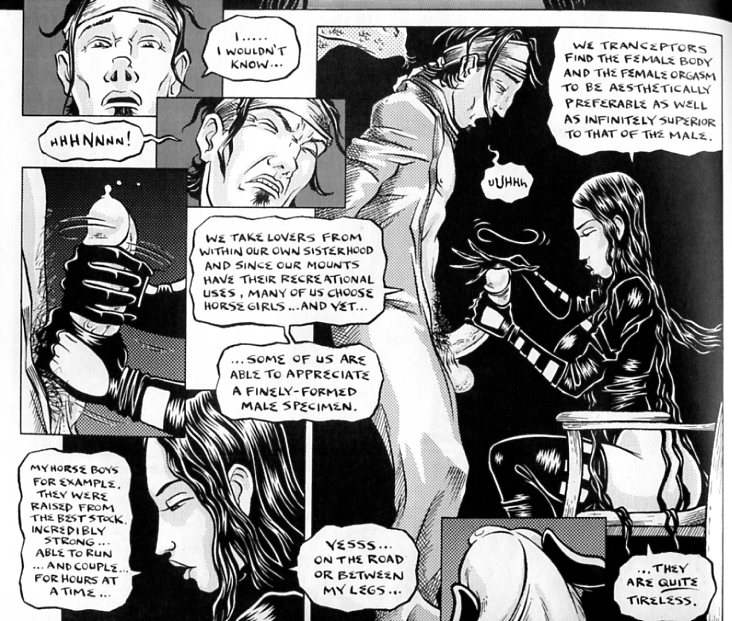

In high-brow sf — or for that matter, in Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie’s historical/porn/literary hybrid comic *Lost Girls* — this sort of perversity tends to serve as a labored allegory of freedom, mutability, or desire. It’s the pulpy goodness about which the highbrow wax nostalgically literary — as when Moore, for example, laboriously leads his characters into a roomful of costumes in order to drive home the joys of role-playing. In *Tranceptor*, on the other hand, the perversion is weighted, not by exegesis, but by pulp tropes. For example the Tranceptors are treated like typical mysterious sci-fi matriarch — say one of the Bene Gesserit from *Dune*. In this context, when the seated Ravanna reaches into Raika’s pants and casually pulls out his penis, it comes across as both funny and weirdly transgressive — especially since Sslthsss is holding his arms so he can’t escape. Over the following two-page hand-job, Conlon and Manning use a range of hysterically intricate motion lines to show her finger motions, while all the time she natters on like a typical scheming villainess.

The last panel of the sequence, in which we are looking down at Ravanna from Raika’s viewpoint as she looks up at him — is a blend of dominant and submissive fantasies bound up with genre clichés into one supremely sexy package.

In Michael Manning’s Spidergarden series, moments like this are woven together in a seamless whole, creating a world in which gender, sexuality, and identity flow and break down in a humid orgy of paranoia and soap-opera romance. Tranceptor hasn’t yet quite reached those heights, though their are hints that it might. Most promising is the series obsessive doubling. The second issue is split between the scenes with the Tranceptor (so bright they almost seem washed out) and those with Ravanna (very dark, with half-toned greys against solid black backgrounds and the shadowy Sslthsss lurking in the background.) The dark/light binary is mirrored and extended by others; there are two identical horse girls, two identical horse boys, two Tranceptors, two young men taken from the station (Raika by Ravanna, Hyu by the Tranceptor.) Where all this is leading isn’t exactly clear at this point in the series. But good vs. evil and blatantly contrasting nemeses are tried and true genre devices — and a genre device is, really, just another name for a particular cathexes of possibility and desire. In this sense, porn isn’t just a genre: it’s the genre. No wonder Conlon and Manning are able to make such perfect pulp out of it.