Appropriated from text scans of The Comics Journal #241 (April 2002). As such typos and grammatical mistakes will be numerous.

Images read from right to left. English translations of Ikkyu’s poetry taken from Stephen Berg’s Crow with No Mouth, Jon Carter Covell’s Zen’s Core: Ikkyu‘s Freedom and John Stevens’ Zen Masters.

One pause between each crow’s

Reckless shriek Ikkyu Ikkyu Ikkyu

As a child, and already showing traces of his life-long distaste for all things hypocritical, Ikkyu Sojun was noted for his precocious intelligence and worldly wisdom. As a monk, wandering the cities and countryside of medieval Japan, he was known both as an ascetic and a libertine, a paradox which has dearly fed his reputation during modern times. He was a poet capable of the profundity of a work such as Skeletons (Gaikotsu; his most famous work concerning a philosophical discussion about Zen and life with a group of skeletons) and the uninhibited passions displayed in his more earthly verse (“A beautiful woman’s hot vagina’s full of love; I’ve given up trying to put out the fire of my body”).

He was a monk who deprived himself of various amenities and honors throughout his life, and yet drank to excess and felt no shame in having a tumble in bed with a comely woman. At the age of 77, he met and fell in love with the Lady Shin, a blind 25-year old minstrel; elevating her by his words and poetry to hitherto unknown heights in the history of Zen. He is considered by many to be Japan’s greatest Zen master.

The name, Ikkyu (which literally means “one pause”), indicates the space between conception and death and thus “this lifetime.” In his 1000-page graphic novel, Hisashi Sakaguchi melds history, legend and spectacle with more subtle matters: religious devotion and the moral and spiritual dilemmas in the creation of art. This amalgamation of fact and fiction is important since the life of Japan’s most famous Zen master has been clouded by tradition and time.

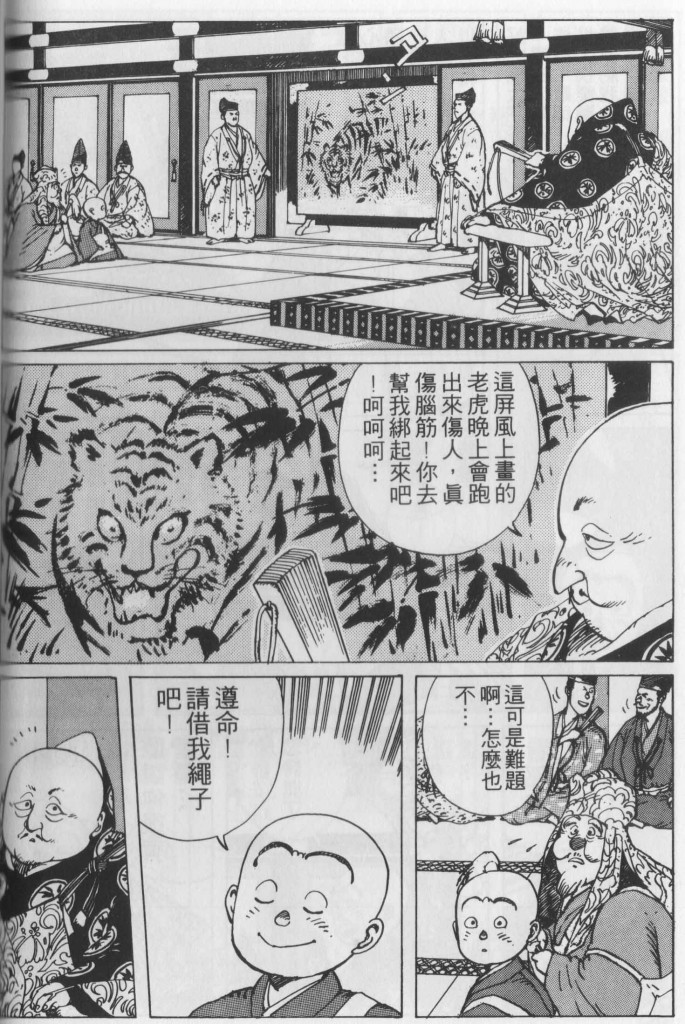

Some of the most famous stories concerning Ikkyu have arisen from various anecdotes about his childhood in Ankoku-ji, a Zen Buddhist temple. For brevity’s sake, these have been combined into single tales by Sakaguchi. One notable episode occurs in the courts of the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, who asks the young Ikkyu to bind a tiger depicted in a screen painting. In response to this, Ikkyu asks for some rope and when given these implements promptly requests that the shogun drive the tiger from the painting for his feat to be accomplished.

This oft-related tale is united with another story (not usually involving Yoshimitsu) in which Ikkyu is presented with a dish of fish and vegetables which he readily begins to devour. When rebuked for consuming the fish, Ikkyu responds that his mouth is like the Kamakura Highway upon which all beasts travel freely. Angered by his comment, the shogun draws his sword and, pointing it at Ikkyu, inquires how its blade would go down. Ikkyu replies that the sword is not permitted passage down his mouth since he cannot allow dangerous items to pass through his mouth (this being the very orifice by which he asks Buddha for peace and safety).

This fabled meeting is of some importance, as tradition has it that Ikkyu was the first-born son of the emperor Go Komatsu and his favorite concubine (said to be a daughter of the southern senior imperial lineage). By the time of Ikkyu’s birth, the Ashikaga shoguns had manipulated the situation such that the Northern junior imperial line was in the ascendant and a child with blood from the defeated Southern line was no longer politically acceptable. As such, Ikkyu’s mother was removed from the imperial palace and gave birth to Ikkyu in the confines of a private residence. Ikkyu’s bitterness concerning this abandonment is a theme that recurs throughout his poetry even in later life.

* * *

The first part of Sakaguchi’s tale is played out against the backdrop of the Muromachi period, an era characterized by the reopening of trade with China, a flourishing of the arts, and the erection of various architectural masterpieces, including the famous Kinaku-ji (Golden Pavilion). Sakaguchi takes care to ground his work in the rich historical framework of the times, creating a web of connections between Ikkyu and some of Noh’s pre eminent practitioners. Zen permeates the characters’ lives; their personalities reflecting the author’s thoughts concerning the preservation of a certain honor and truth, as characters become mired in disputes over artistic and religious integrity.

The interweaving of Zen with the cultural and the political lives of the Japanese elite is not an invention on Sakaguchi’s part. The organization of the main Zen monastic complexes into the Five Mountains (gozan) administrative system towards the beginning of the Muromachi period allowed a significant extension of Zen’s cultural influence. Two other eminent Five Mountains monks, Zekkai Chushin and Gido Shushin, were also important political advisors and tutors to the shoguns of their time (including Yoshimitsu).

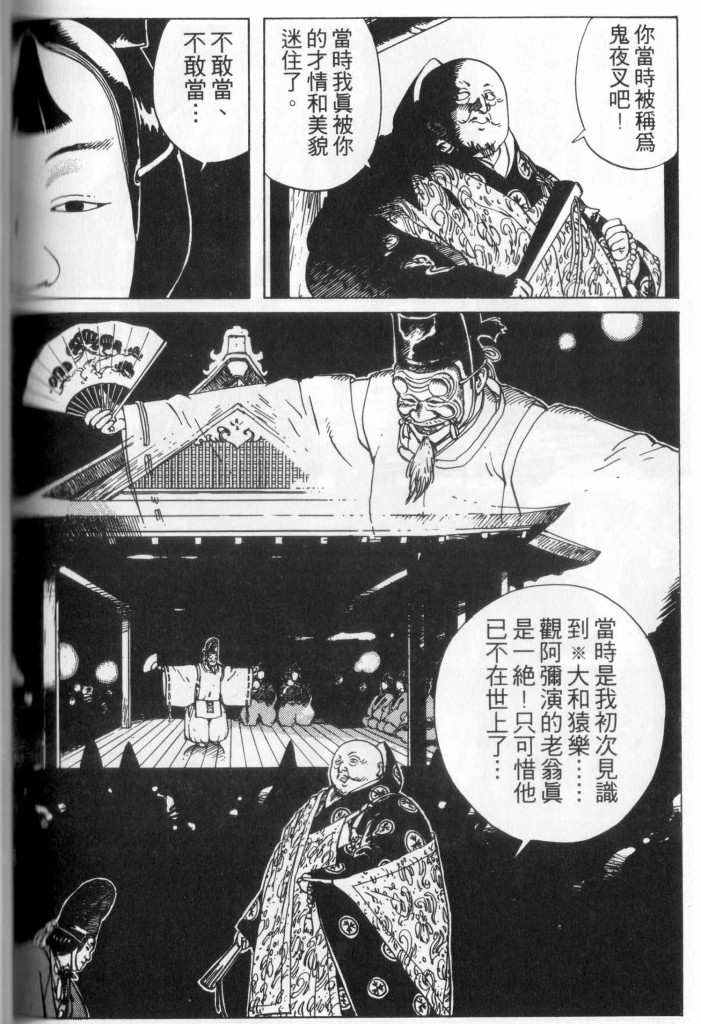

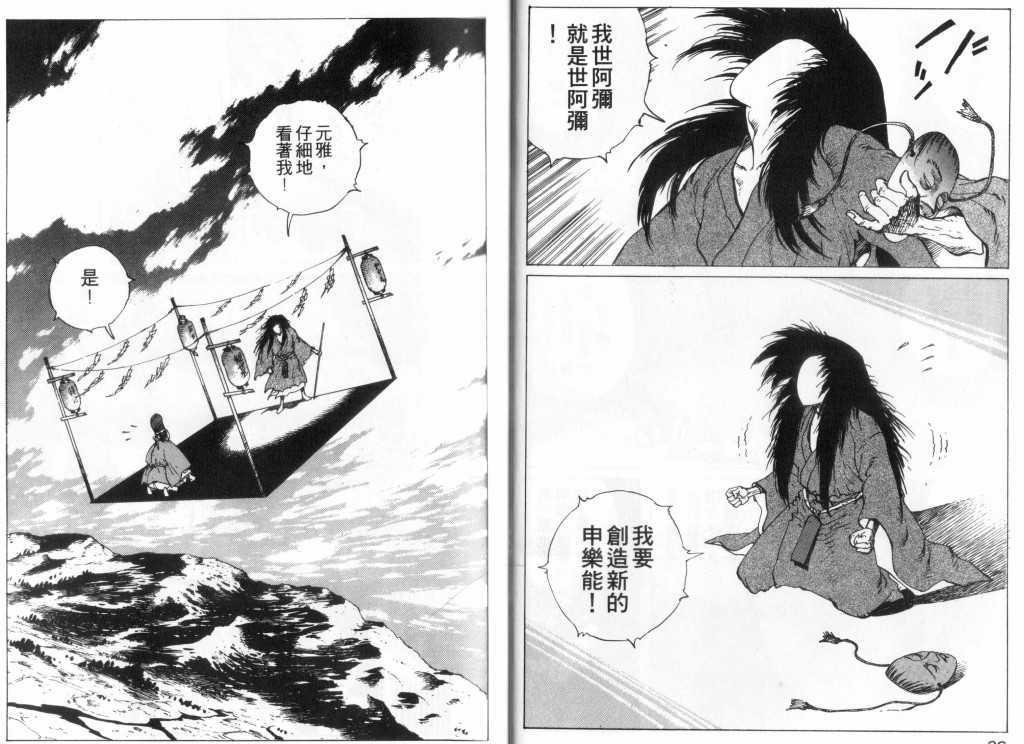

With specific relevance to the manga, the Muromachi period has been noted for a flowering of Noh theatre. Zeami Motokiyo (1363-1443), classical Noh’s finest playwright, lived during this period and his triumphs and misfortunes are intertwined with those of Ikkyu in Sakaguchi’s series.

In the manga, Zeami and his son Motomasa are always depicted wearing their Noh masks, whether onstage or in conversation with their peers or patrons — their lives becoming a stage upon which art and politics are discussed. Zeami is usually seen wearing the mask depicting an old man. The main exception to this occurs when he is reminiscing upon the past and his first performances in front of Yoshimitsu where he is seen wearing the mask of a young man.

This narrative device goes beyond a utilitarian depiction of advancing age. Thomas Blenman Hare (writing in Zeami’s Style) states that in Zeami’s list of six typical plays in the Aged Mode, “in all but one of these, the old man is actually a god in disguise; only one of Zeami’s ‘old men’ is actually a man.” Hare, quoting an old Zeami manuscript, indicates that the Aged Mode “produces an air of divinity and utter tranquility,” words which perfectly describe Zeami’s final state in the closing volume of Ikkyu.

On’ami (Zeami’s nephew and Motomasa’s nemesis in the manga) on the other hand is invariably seen wearing the mask of a demon (oni). It has been suggested that he preferred such plays and excelled at them where Zeami slowly began to renounce such roles. Hare writes that Zeami had “come to reject entirely the role of the true demon-hearted demon” in later life, and with regards demon Noh, he quotes the famous playwright and actor as writing, “This is unknown in our school of Noh.”

Noh presents itself as a perfect mirror for the unspoken mysteries upon which Ikkyu’s life turns. The two cornerstones of Noh are monomane (“an imitation of things”) and yugen (meaning “mystery and depth”), aspects which reflect the very real political intrigues of the manga and the half-hidden wonders in which Ikkyu periodically partakes. There is even reason to believe that Sakaguchi’s work as a whole is partially constructed on the principles of Noh, with the story of the main character (the shite, in this case the Ashikaga shogun and, at other times, Zeami) being clarified and deepened by the philosophical and personal interrogations of the waki (the secondary character, in many instances a traveling priest which fits the description of Ikkyu).

The parallels Sakaguchi suggests are not extravagant. Critics point to the Zen influence in Zeami’s Kakyo, which the author describs as “a summary in six chapters and twelve articles of what I myself have learned about the art.” He is also said to have had encounters with a number of prominent Zen priests during his lifetime. Better documented is Ikkyu’s relationship (recounted in the manga) with the Noh actor Komparu Zenchiku, Zeami’s son-in-law and one of Noh’s great aestheticians. Ikkyu wrote at least two poems in praise of Zenchiku during his lifetime and there is correspondence demonstrating a close relationship between Zeami and his son-in-law. In this way, the separate paths traveled by Ikkyu and Zeami — delineated with exquisite care by Sakaguchi in his manga — are brought to a partial resolution in the person of Zenchiku when he encounters and debates an arrogant yet visibly confused On’ami in the closing volume of the manga.

Filled with shame I can barely hold my tongue.

Zen words are overwhelmed and demonic forces emerge victorious.

These monks are supposed to lecture on Zen,

But all theye do is boast of family history.

Ikkyu left Ankoku-ji (following a short period at Mibu temple) in 1410. Disgusted by the political machinations of the masters of the Gozan monasteries of Kyoto, he left behind the verses above depicting his frustrations with the corruption and unctuousness of his fellow monks; feelings which he would carry with him throughout his life, for Ikkyu is known for his disdain of Five Mountains Zen.

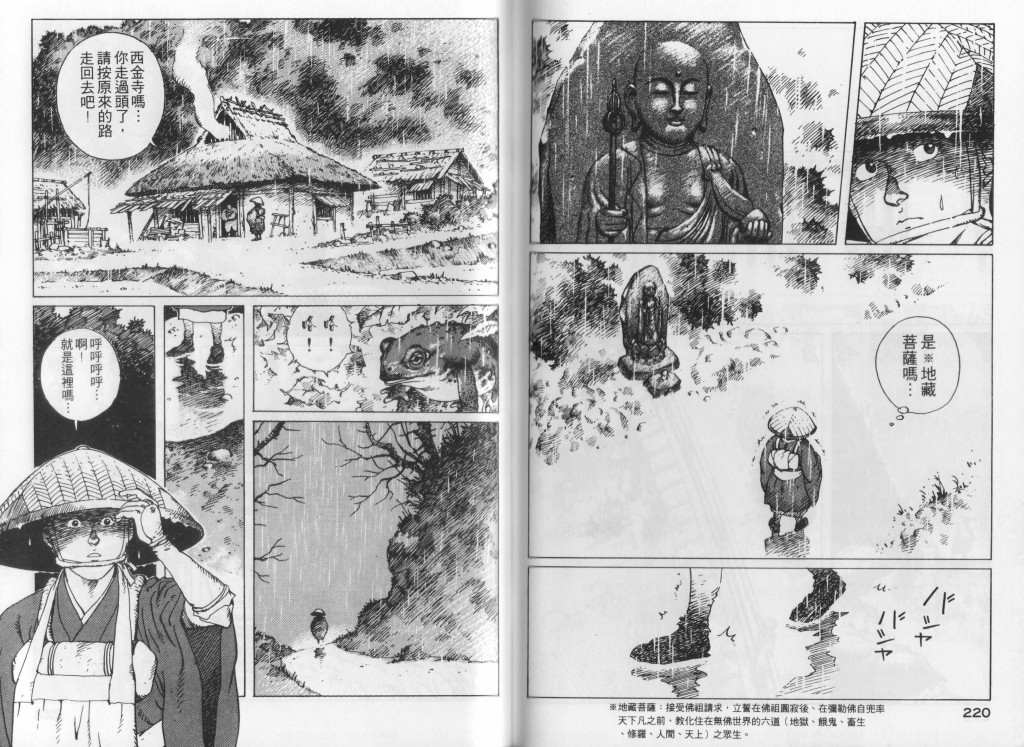

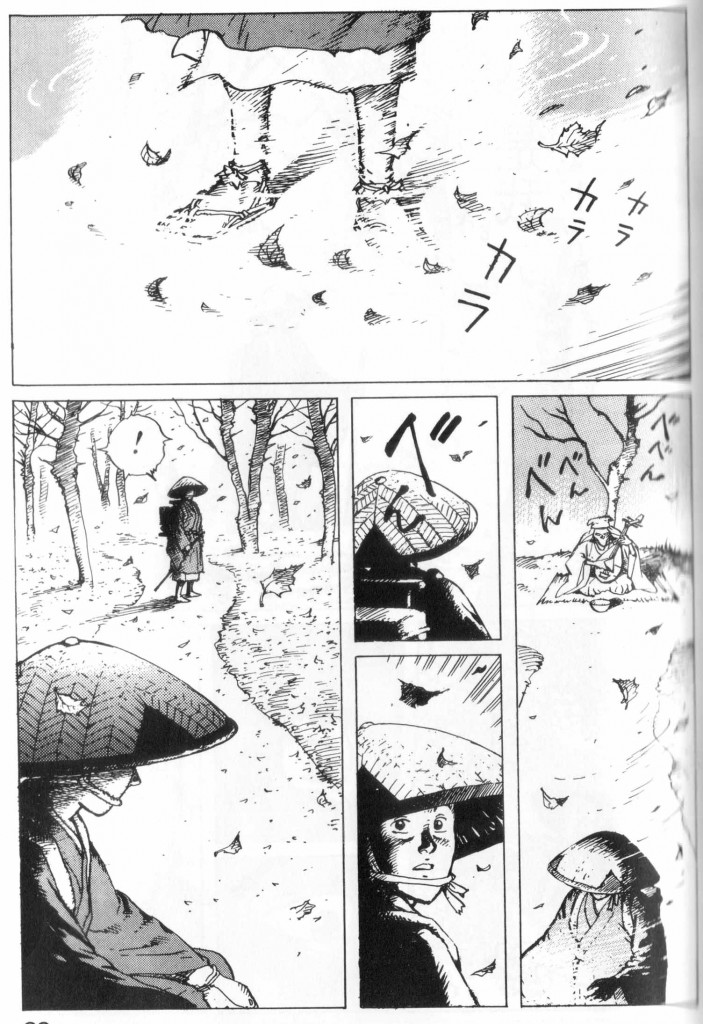

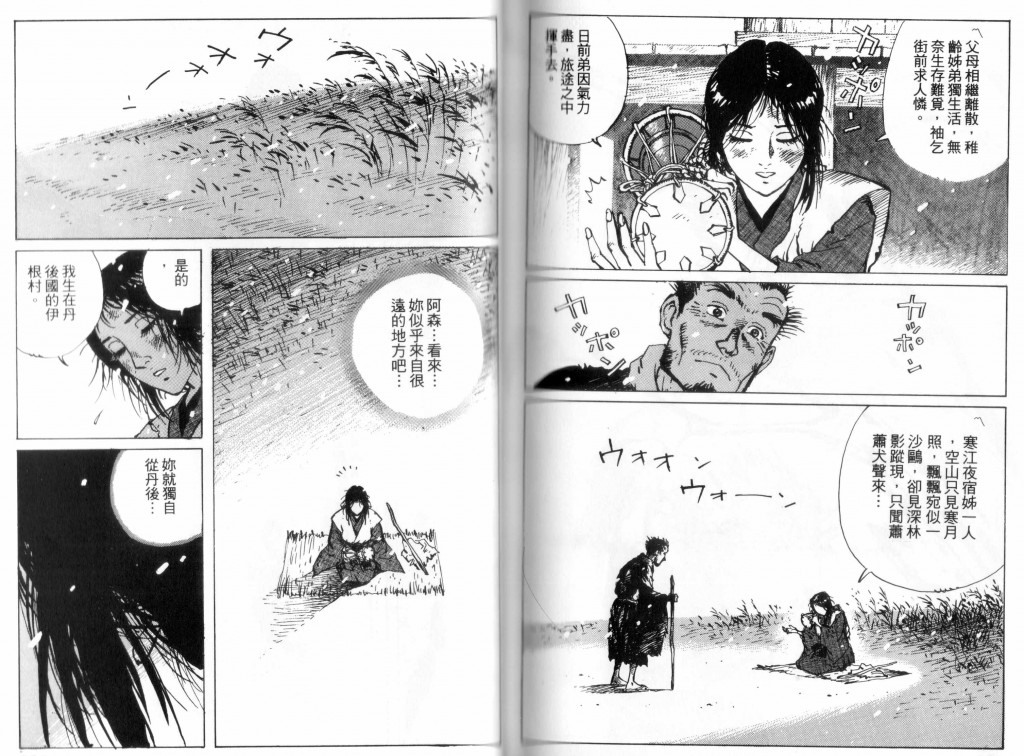

Soon after leaving Ankoku-ji, he begins to train under a new master, Ken’o, who he meets after meditating on his life while staring at a lotus flower. This occurs a few pages after Zeami is seen doing the same while contemplating his own treatise on Noh [1]. Ikkyu first chances upon Ken’o as he is distributing food offerings to the children of a shanty town. He later finds him at a ramshackle hut (defiantly called a temple) outside Kyoto. Life under Ken’o proves to be one of ceaseless toil compared to the comforts of Ankoku-ji. Apart from the spartan lifestyle, he is mysteriously chided for getting up in the middle of the night to meditate. When seeking solitude for the same in the countryside, Ikkyu is disturbed by some mischievous children, which he takes as a distant rebuke by his master for committing the same “error.”

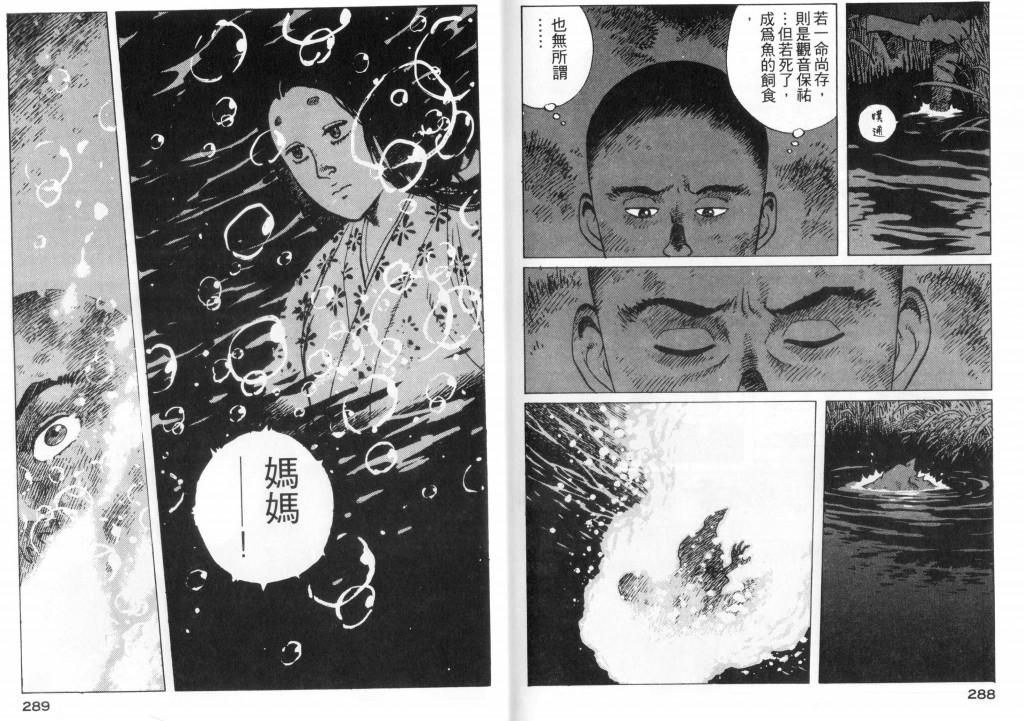

Upon returning from this period of solitude, he is roundly beaten by his master who, noticing the mud on his robe, realizes that his pupil has been disobeying his orders. It is only at Ken’o’s deathbed that Ikkyu discovers the reasons for his frequent beatings. Ken’o explains that he has been disciplining his intemperate state of mind. Together with his master’s passing, this revelation causes Ikkyu to sink into a deep depression. Wandering aimlessly through the countryside, he soon resolves to put an end to his life by drowning himself in Lake Biwa. He decides against this on remembering his mother and the sorrow this would cause her.

The second volume of Ikkyu follows upon this aborted suicide and contains a detailed look at the young monk’s life under a new master, Kaso Sodon, who belonged to the harsh Daito tradition of Zen. Ikkyu endures a week-long wait at the gate of Kaso’s austere Lake Biwa retreat in order to prove his determination to become his disciple. The longest and most lyrical passages in this section of the manga are devoted to two significant moments of realization and enlightenment.

In the first instance, Ikkyu pierces a zen koan from the 15th case of the Gateless Gate (Mumonkan) involving an exchange between the monk Dongshan Shouchu and the Chinese Zen Master Yun-men Wenyan. Ikkyu penetrates the zoan upon hearing a blind minstrel singing a song from the Heike Monogatari, namely the tale of Lady Giyo and the general, Taira no Kiyomori — a tale of betrayal and unfaithful affections which exposes and expunges his long-held recriminations against his father, the emperor, for abandoning his mother amidst similar court intrigues. Upon presenting his solution to the koan to Kaso, Ikkyu is finally presented with the name by which he is known to this day (he was previously known as Shuken).

Ten dumb years I wanted things to be different furious proud I still feel it one summer midnight in my little boat on Lake Biwa caaaawweeeee father when I was a boy you left now I forgive you

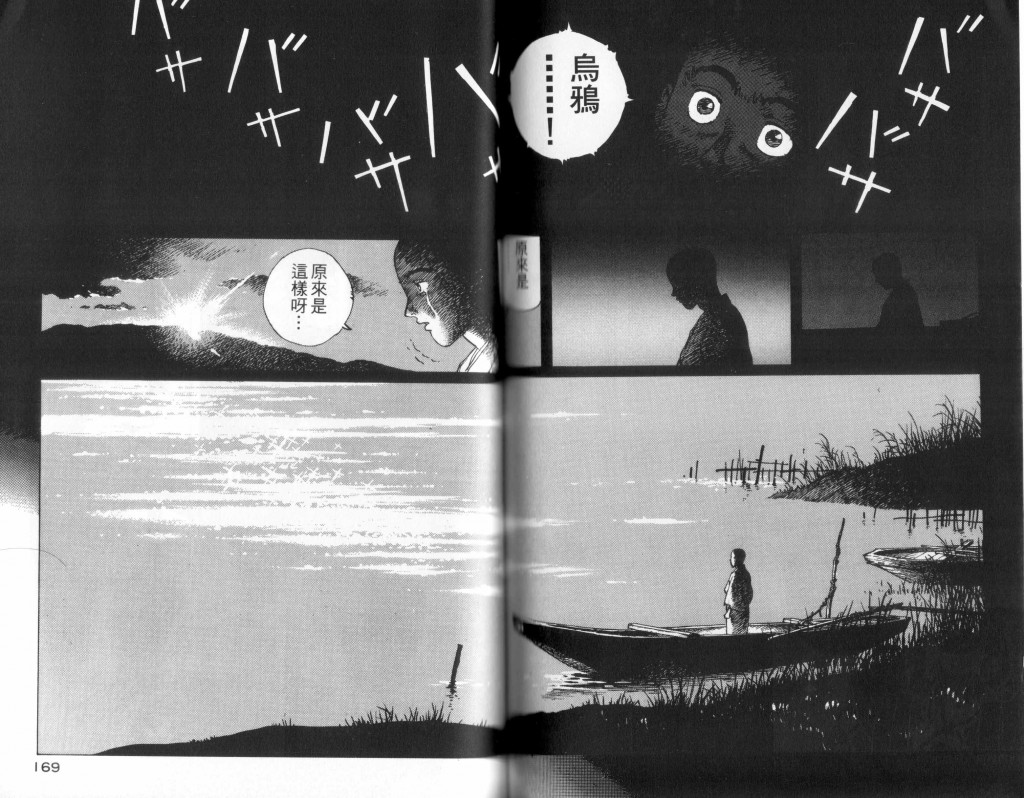

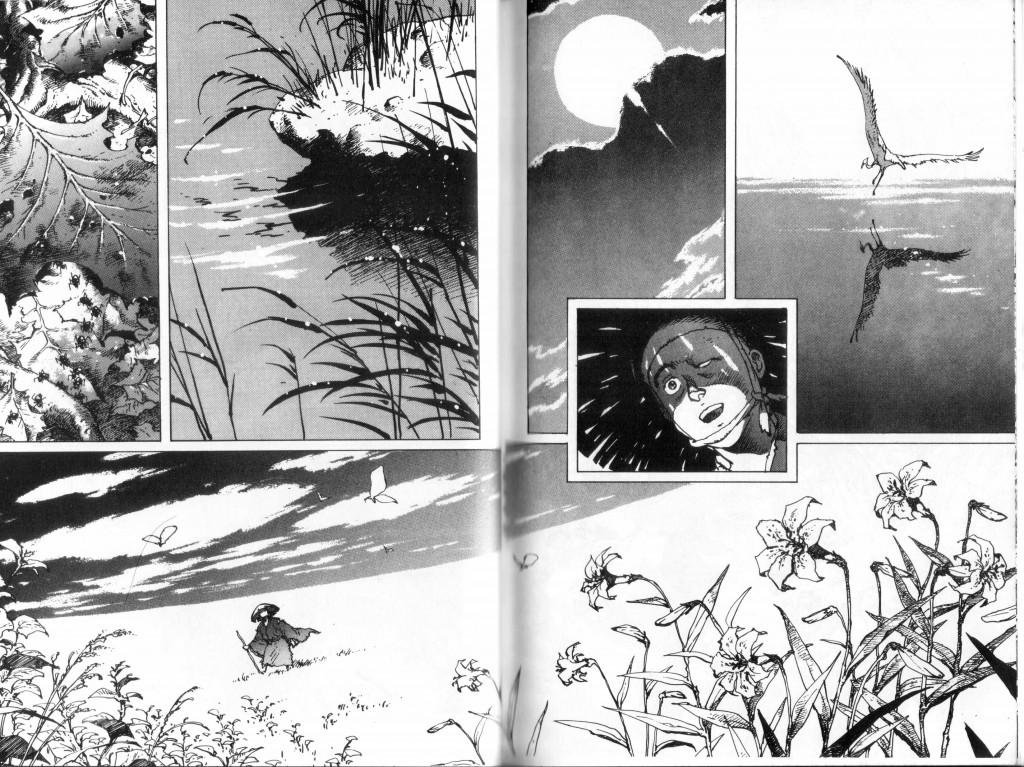

The other key moment in Ikkyu’s life under Kaso is found while he is meditating in a boat by Lake Biwa. In contrast to his first satori — which is depicted as a sublime moment of tranquility and self-awareness — this second important spiritual juncture is depicted as a cry heard through dense dark night, single and distinct and stretched across two pages.

Sakaguchi’s interpretation of this moment unfolds through a conversation with his master and reflects the feelings he expressed in a poem written in response to this moment of enlightenment:

For ten years I was in turmoil,

Seething and angry, but now my time has come!

The crow laughs, an Arhat emerges from the filth,

And in the sunlight of Chao-yang, a jade beauty sings

The crow’s cry chases away all memories his bitterness over his mother’s (the jade beauty) expulsion from the royal court, leaving him free to feel at one with his surroundings.

Life is like a dream and goes with the speed of lightning.

It is like a dew-drop in the morning;

it soon falls and is broken …

“Here are shown the struggles and the sins of mortals, and the audience, even while they sit for pleasure, will begin to think about Buddha and the coming world on Oni-No or the Noh of Spirits” – from the Kadensho or Secret Book of Noh.

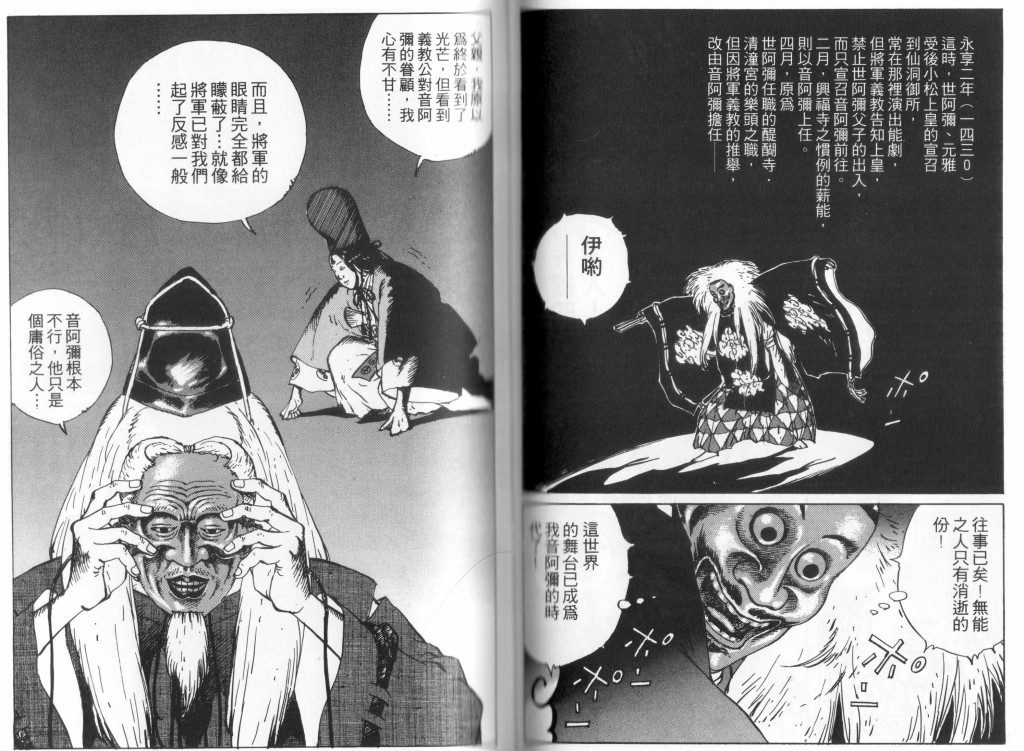

The third volume of Sakaguchi’s manga segues into the rivalry between Motomasa and On’ami (presented to us in the mask of a demon and who the audience of the time sees as Zeami’s heir). This drama carries implications beyond mere questions of succession.

On’ami’s fortunes began to rise (as Zeami and Motomasa’s declined) during the reign of the shogun Yoshinori (one of Yoshimitsu’s sons). By 1429, both father and son were excluded from further appearances at the Sento Imperial Palace, and in 1430 the musical directorship at Kiyotaki shrine was taken from Motomasa and given to On’ami.

In the manga, this dispute mirrors Ikkyu’s exclusion from the mainstream of Zen thinking and provides a secular reflection of Ikkyu’s own conflict with Kaso’s chief disciple, Yoso, over their master’s legacy. Their conflict encompassed corruption, ambition, women, sexuality, and other contentious ideas concerning Zen. Discussions of carnal and romantic love would seem out of place in a story concerning a monk but they are central to any understanding of Ikkyu and his interpretation of Zen.

Each of Ikkyu’s encounters with women in the manga contains stepping stones to further enlightenment, each meeting offering both temptation and sustenance. There is a moving episode involving a young prostitute whom he befriends while she is quietly offering herself in the window of a brothel, selling her body to feed her family. In another instance, he meets and is sexually tempted by a girl who helps him after he has been beaten up in an encounter with a spiritually corrupt monk. Another encounter with a dying prostitute prompts a moment of deep introspection.

All this is played out in the light of Yoso’s somewhat abusive and pecuniary attitude towards women. Over the course of his rise to prominence as chief abbot of Daitoku-ji temple, Yoso is seen propounding on the unclean nature of women and their inability to achieve enlightenment.

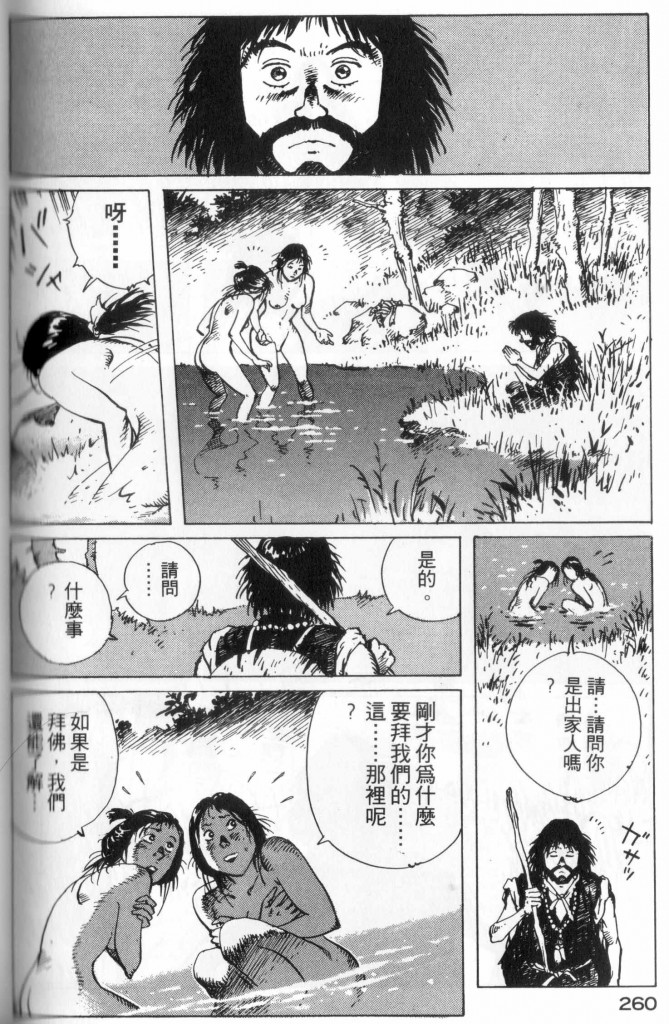

Ikkyu was of the opposite opinion. Sakaguchi illustrates this by recounting his encounter with some nude women bathing in a pond. On chancing upon the stunned women, Ikkyu bows reverently towards their genitalia and proceeds along his way. When pressed for the reasons for his actions, he gently chides the popular views earlier recited by Yoso and further suggest that women represent a great and unparalleled treasure, as all humans — however great or lowly — proceed from them.

In his short biography of Ikkyu, John Stevens relates the story that furnishes the source material for this scene, providing a more direct response by Ikkyu with regards this eccentric view of women:

Woman are the source from which every being has come.

including the Buddha and Bodhidharma.

Jon Carter Covell (Zen’s Core: Ikkyus’ Freedom) in explaining Ikkyu’s relation to the “red thread” of passion puts it thus:

“If, from childbirth, man is already entangled with the feminine, his violent denial of it later shows a lack of enlightenment.”

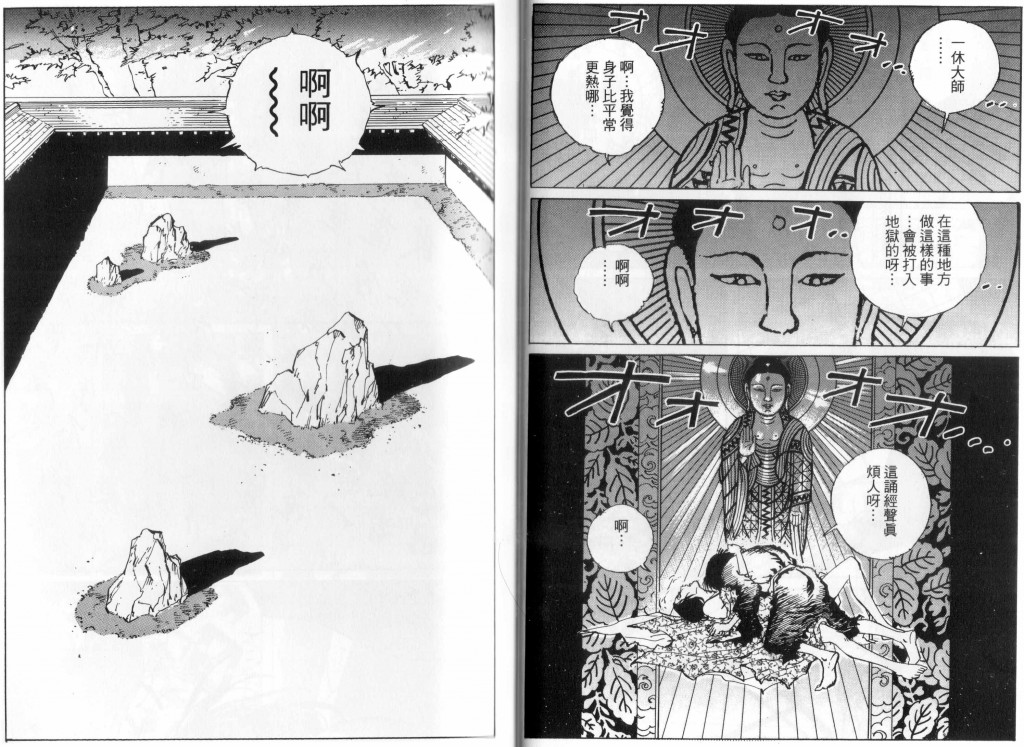

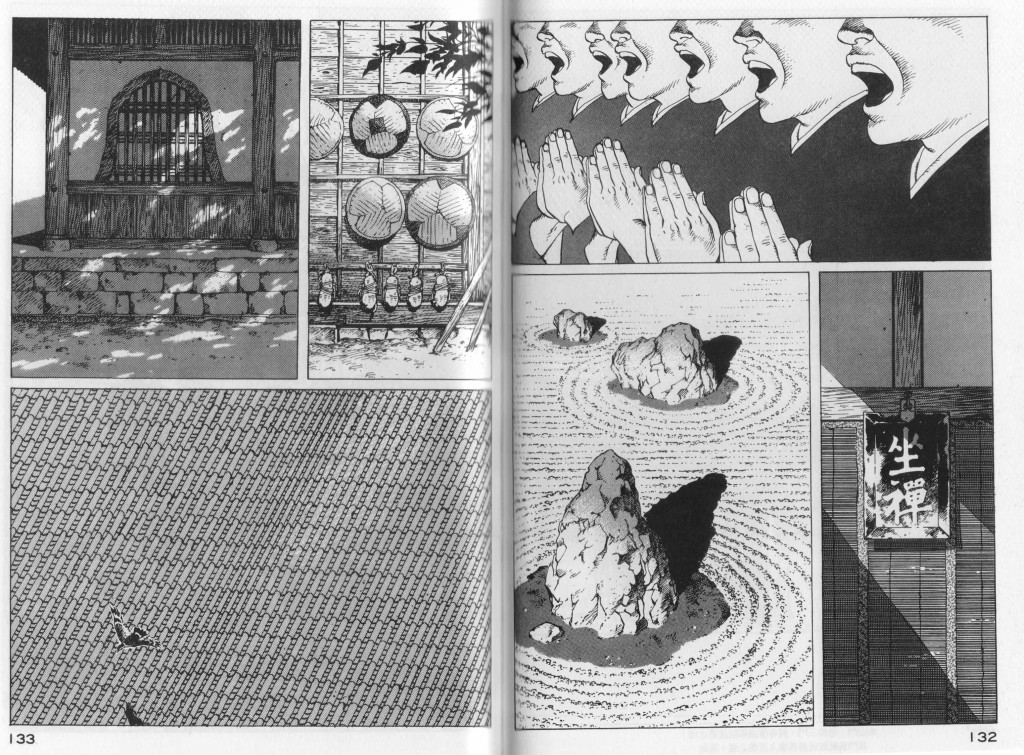

Sakaguchi further elaborates upon this important element in Ikkyus’ beliefs in his poetic verbal duel with a famous courtesan. Their relationship is consummated in an abandoned house a stone’s throw from where his fellow monks are accumulating earthly offerings as a form of veneration and worship. Juxtaposed against the chanting of the monks from the temple, their sounds of sexual ecstasy resound across a Zen garden.

Covell suggests that “sex had almost become a religious ‘rite’ to him”. With respect to his experiences with prostitutes, Ikkyu once opined:

When as a rakan I “rose above the dust,”

I was still not in the (real) Buddha Land;

But once I entered a brothel, tremendous wisdom occurred.

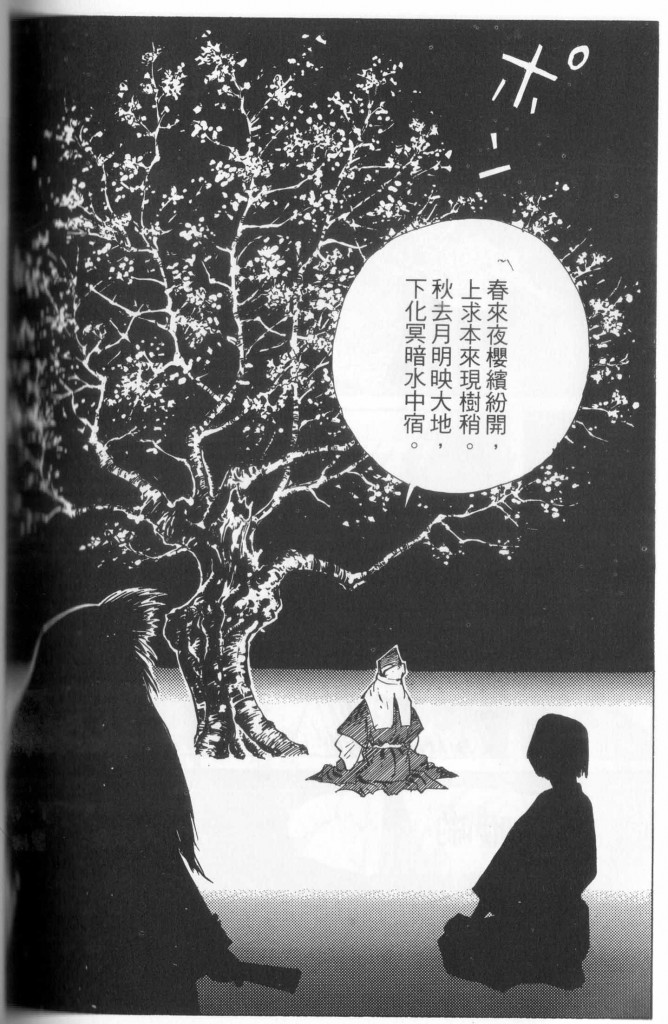

Of all the women Ikkyu encounters, Sakaguchi devotes the greatest space to Lady Shin, the object of his passion in the final years of his life. When Shin is first seen by Ikkyu in the manga, she is seen kneeling while playing a small hand-drum in homage to a famous double portrait commissioned by Ikkyu himself (now found in the Masaki Museum in Osaka).

It was a love both romantic and carnal. In “Watching the Beauty Shin in the Midst of Her Siesta”, he writes:

The most elegant beauty of her generation.

Her love songs for a banquet are the newest.

She sings so naively, it pierces my heart; a dimple appears in her cheek.

Shin is like a begonia in the “Heavenly Treasure” period.

In “If My Hands Were Like Shin’s,” he writes with unabashed frankness, “When my ‘jeweled stalk’ is weak, she makes it sprout.” In the manga, the moment in which Shin finally expresses her love for Ikkyu is presented almost as a moment of enlightenment, the pacing of this sequence adopting a tone similar to that of his second satori.

The couple are seen in the midst of a bamboo grove with the wind rustling through the branches as if in physical and pictorial demonstration of the concept of furyu (meaning “wind flow”), an aesthetic ideal which permeates Ikkyu’s art and a term which he used to praise those persons with whom he was most intimate.

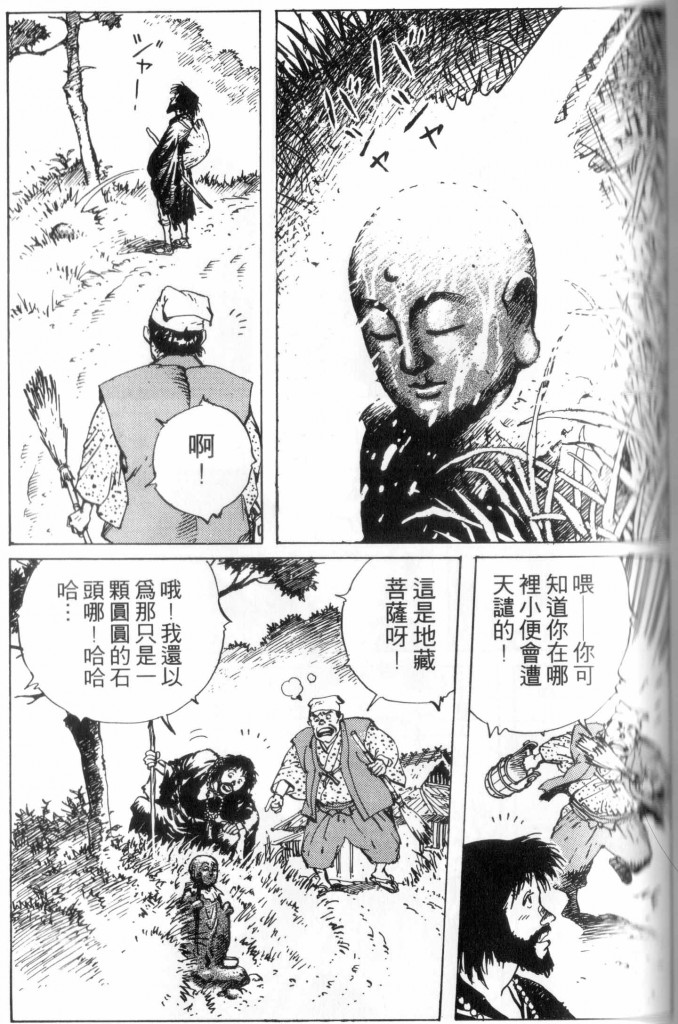

Ikkyu’s non-conformist ways extended beyond his unapologetic enjoyment of sex, meat, and wine. Sakaguchi joyfully depicts a host of his exasperating ways, from urinating on a roadside stone Buddha to burning a revered wooden Buddha figurine in order to keep the Buddha in his heart” warm.

Ikkyu is seen taking food offerings from gravesites (a pointless gesture in his view) and, in instructing a deeply religious samurai who is stumped by a few words from some Buddhist scripture, suggests using the name of his favorite food in place of the words he cannot read. It is this freedom and irreverence that has endeared him to late twentieth century readers.

* * *

Born in 1946, Hisashi Sakaguchi was a one time assistant to Osamu Tezuka and was known for his work on animation projects such as Astro Boy and The Jungle Emperor. He died soon after completing Ikkyu, his masterwork. His other manga include a science fiction story called Version (available in English) and the much-praised but slightly melodramatic Flowers of Stone (sometimes called Partisan), which concerns the partisan action in Yugoslavia during World War II. The latter book is of particular interest being an early example of Sakaguchi’s attention to historical detail both in dress and architecture.

In Ikkyu, Sakaguchi navigates a meandering path through childhood tales of wisdom, initiations into homosexuality, political and cultural intrigues, and sexual and romantic love. The work presents itself as pure narrative, but is also held together by a number of unifying threads.

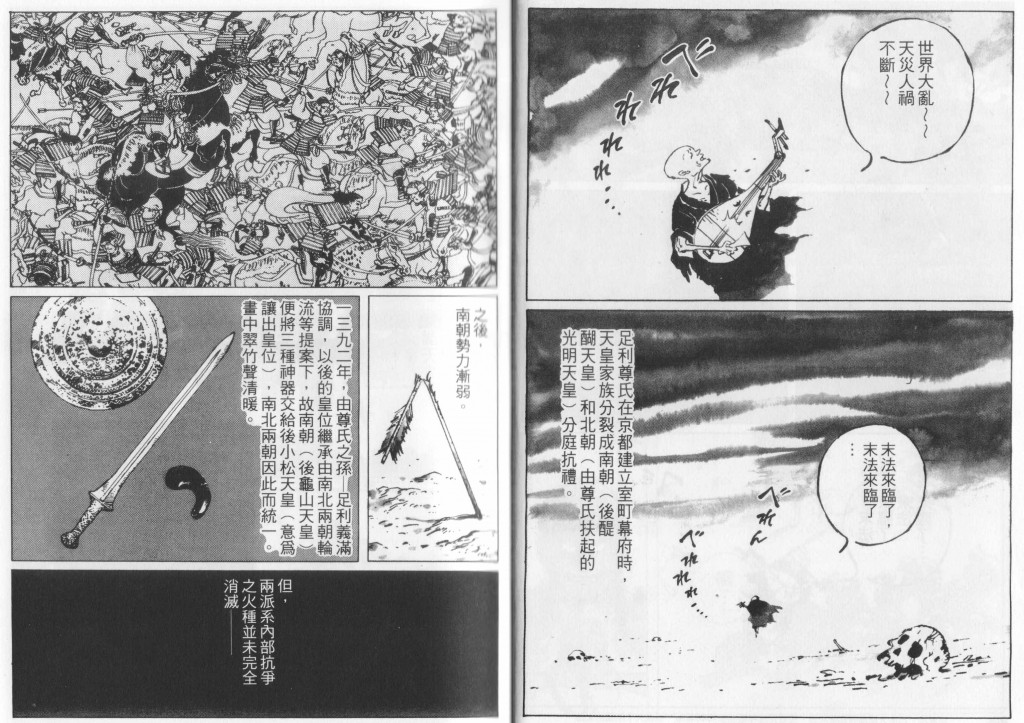

One motif that repeats itself throughout the novel can be seen in its early pages, where a drunk and irreverent Ikkyu is juxtaposed with wartime massacres. An ambiguous integration is forged between these horrors and the songs and chants of wandering monks.

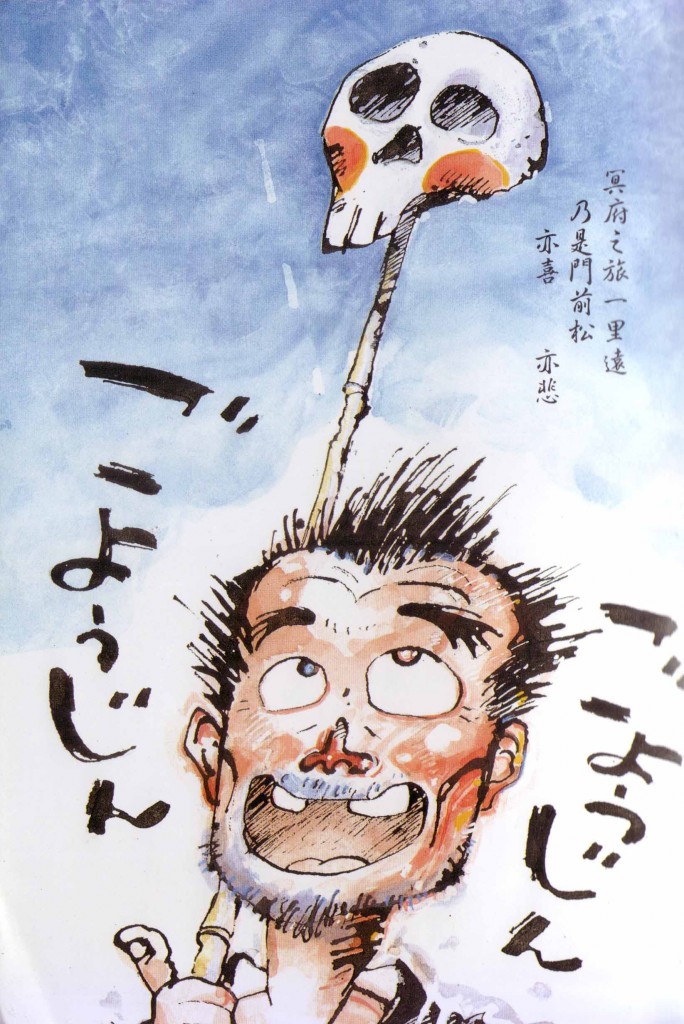

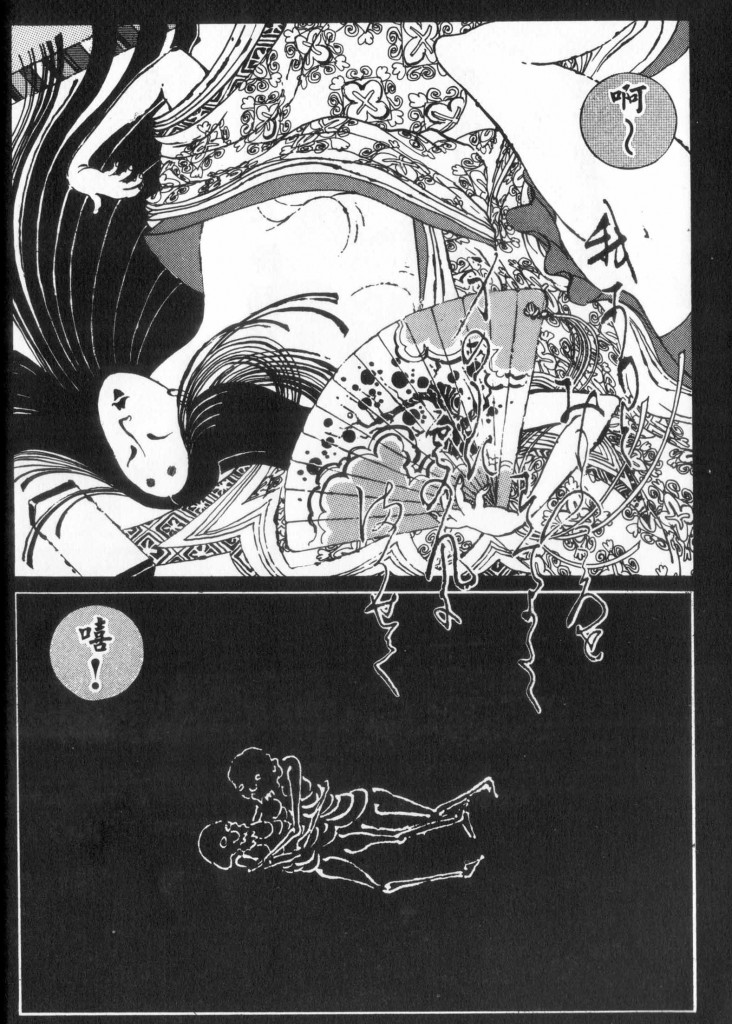

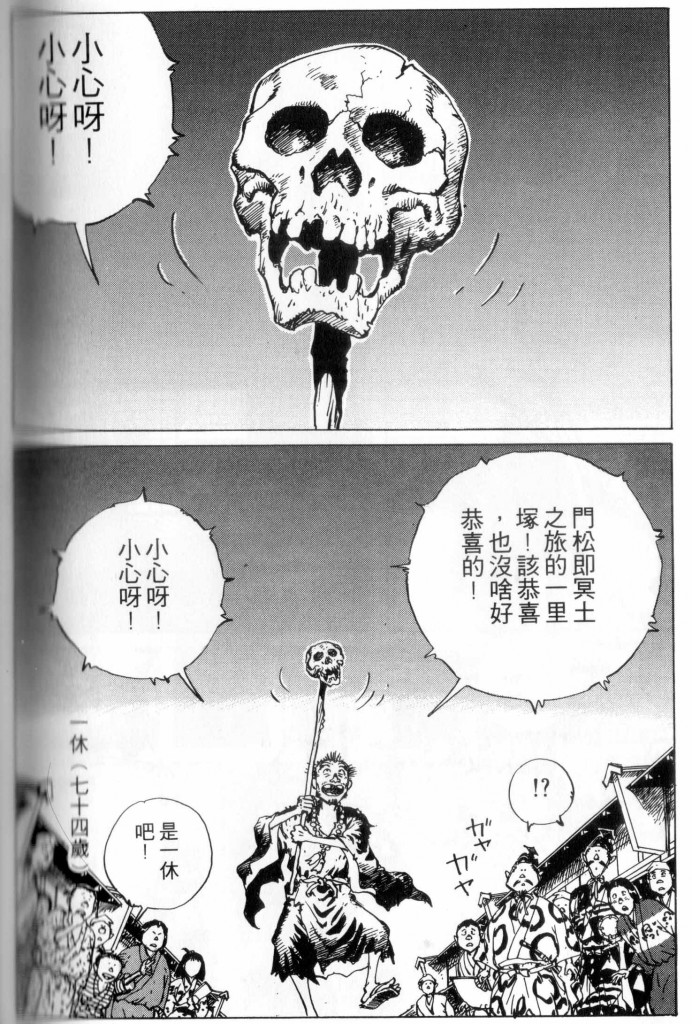

One of Ikkyu’s responses to the seemingly endless cycle of famines and natural disasters during his lifetime was to write one of Japan’s most famous books on the subject of death, Skeletons. It was written in the vernacular (as opposed to his usual classical Chinese poetry) in order to appeal to the common man, the better to instruct him on mortality and Zen. Ikkyu is seen drawing Skeletons in the fourth volume of the manga and is later seen in a dramatization of a famous print in which he is seen carrying a pole with a human skull at its tip.

The landscape of corpses and skeletons which populate Sakaguchi’s novel are both a reflection of the seeds of Ikkyu’s famous work and a dramatic depiction of the very real situation of uncleared and unburied bodies which lined the streets of Kyoto.

There are also dear parallels drawn between Noh and the narrative of the manga. By signposting significant periods in Ikkyu’s life with short “performances” of Noh, Sakaguchi allows us to seek parallels between the demarcations in the manga and the prescribed arrangement of plays in a day of Noh performances.

Such a performance begins with a Shugen, or congratulatory piece, followed by the Shura (battle-piece), the Kazura or Onna-mono (“wig-pieces or pieces for females”), an Oni-No, a fifth piece “which has some bearing upon the moral duties of man,” and ends with another Shugen, “to congratulate and call down blessings on the lords present, the actors themselves, and the place.”

Another way of understanding the thrust of Sakaguchi’s presentation can be found in Covell’s book, which illuminates Ikkyu’s life in relation to “The Ox-Herding Series” (the ox representing the “Buddha-mind … for which the ego searches”). The series follows an ox-herd on a metaphorical journey from the initial sighting of the “ox” (painting one in the series) to satori (painting eight in the series, represented as white space within an empty circle) in which the seeker understands the “oneness of all phenomena.”

Painting nine concerns “life after satori,” where the enlightened man begins to fully appreciate all the beauty that surrounds him, which “means not only the beauty of flowers but also the beauty of women.” The tenth and final stage is called “Returning to the Marketplace” or Entering the city with Bliss-bestowing Hands” and shows a child encountering Hotei, the rotund god of good luck, who “by his transforming presence brings to all the awakening of their own Buddha-natures.”

Covell quotes Kuo-an’s commentary on the tenth picture stating,

“He is found in company with wine-bibbers and butchers; he and they are all converted into Buddhas.”

Sakaguchi’s understanding of Ikkyu’s life preserves this core of truth; the essence of Ikkyu’s teachings. In the manga, Sakaguchi deemphasizes Ikkyu’s elevation (at the age of 80) to the position of chief abbot of Daitoku-ji by the emperor Go Tsuchimikado, and the massive undertaking of the reconstruction of the temple that had burned down over the course of the Onin War. Instead, it is the very human aspects of the crazy Zen man which are of most interest to the artist.

The manga is faithful to his relationships with the common man and his distinct influence on Japanese culture. In his lifetime, Ikkyu encountered warriors, generals, artists, prostitutes, inn keepers, merchants, thieves, and kings, altering each in his own unmistakable fashion. Ikkyu’s student and Japan’s first tea master, Murata Shuko, would develop — some say in direct collaboration with his master — a new approach to the tea ceremony, one which incorporated a heightened understanding and awareness of Zen. Shuko would also design Zen gardens on which “the love letters which sing of wind and rain, snow and moon,” could be observed; gardens which revel in the wabi aesthetic propounded by Ikkyu. Two other pupils, the renga poets Sogi and Socho, would later develop haiku poetry. It would not be unreasonable to suggest that Sakaguchi must have counted himself a slightly removed student of the master. Dense with historical fact and passionate artistry, Sakaguchi’s forthright and yet mystical work is possessed by the essence of the man and is a testament to his intelligence, spirituality, and artistic vision.

* * *

[1] In the first volume of Ikkyu, Zeami is depicted working on the seventh and final chapter of his seminal and most famous work on the theatre, Fushikaden; a book that has been described as partly a meditation on the teachings of his illustrious father, Kannami. In the chapter in question, Zeami dwells on the aesthetic ideals of Noh, which Hare explains “depends on its existence on the creation of what Zeami terms ‘the flower,’ an effect which is achieved through technical skill and intellectual understanding.”

Excellent article. Sakaguchi’s work is just begging for publication by someone like Vertical or D&Q. I wonder if he’s as forgotten in Japan as Tatsumi supposedly was? He’s certainly far more accomplished than Tatsumi.

Thanks, Steven. You probably deserve some sort of medal for getting through it in the first place.

I have no idea what kind of reputation Sakaguchi has in Japan today, but I suspect that D/Q and Vertical haven’t taken the plunge because the series has very little commercial viability. I mean, who would buy it? There are predictable buying trends in the American manga market and this doesn’t fit in (just like Times of Botchan doesn’t fit in).

Great post, Suat!

If you read French, here it is.

Sorry, that’s the Spanish edition, but there are French and German editions.

I’d be interested in this, but the French edition is out of print and as far as I can see, quite expensive.

I remember having a couple issues of the English version of Sakaguchi’s “Version”, but I can’t for the life of me recall anything about it.

No, it’s definetly not commercial but considering some of the other titles that Vertical & D&Q have published….

I mean, was “Red Colored Elegy” a commercial project? In that sense one could always hope.

Bravo! An extraordinary article about what clearly is a masterpiece.

Elsewhere at HU I’d written, “One could argue that it takes a worthy subject to bump up criticism to a higher level (John Simon on Ingmar Bergman is certainly more richly illuminating than Simon frothing about some Hollywood drek),” and “Old Wine in New Wineskins: Hisashi Sakaguchi’s Ikkyu” certainly serves to prove that suggestion.

Beautifully written (somehow echoing the mood of the work); rich in historic knowledge and understanding of the culture and Buddhism; the sample pages superbly chosen, with Sakaguchi’s artistry, sensitivity, ability to convey a spectrum of moods and brilliance at communicating spiritual and philosophical concepts dazzlingly evident.

There’s even a hilarious “in-joke”:

——————————–

Appropriated from text scans of The Comics Journal #241 (April 2002). As such typos and grammatical mistakes will be numerous.

——————————–

This was written ten years ago, and still no English-language company has published Ikkyu? Hopefully this “republication” of “Old Wine in New Wineskins: Hisashi Sakaguchi’s Ikkyu” at HU will attract more interest in that area…

Thank you, Mike. In reply to your last point, I think the amount of interest in this article sort of proves that Ikkyu should never be published in English. If avoiding insolvency is the goal of course. That the French edition is out of print speaks volumes.

I wonder if Red Colored Elegy broke even or made money. That was one of the least commercial manga D&Q ever published.

Derik: Version probably isn’t worth reading or remembering.

Red Colored Elegy is my favorite manga D&Q has done, so I’m sure it must have been their worst seller.

Not to take away from the delightful read and graphics of an inspiration of mine I have a puzzling question. Who is the intended audience of this very nice work…I mean…the manga sound effects are in katakana…and…not being a reader of kambun..which I am assuming the bubble text to be…I mean..How many Japanese can read kambun? Puzzling. Just saying.

Ah sorry, I should have made it clear. The scans are from a Chinese translation of the manga. So it’s not the original Japanese version. Though I do believe Ikkyu did write his poetry in classical Chinese.