Yet who shall declare the dark theme a positive handicap? Radiant with beauty, the Cup of the Ptolemies was carven of onyx.

– Supernatural Horror in Literature, H. P. Lovecraft

Comics and its continuities have long been happy receptacles for H. P. Lovecraft and his machinations. Noah’s appreciation of the author’s “ham-fisted” charms can be found in the archives of this site together with a review of a predictably mediocre adaptation, the Eureka Graphic Classics production of H. P. Lovecraft.

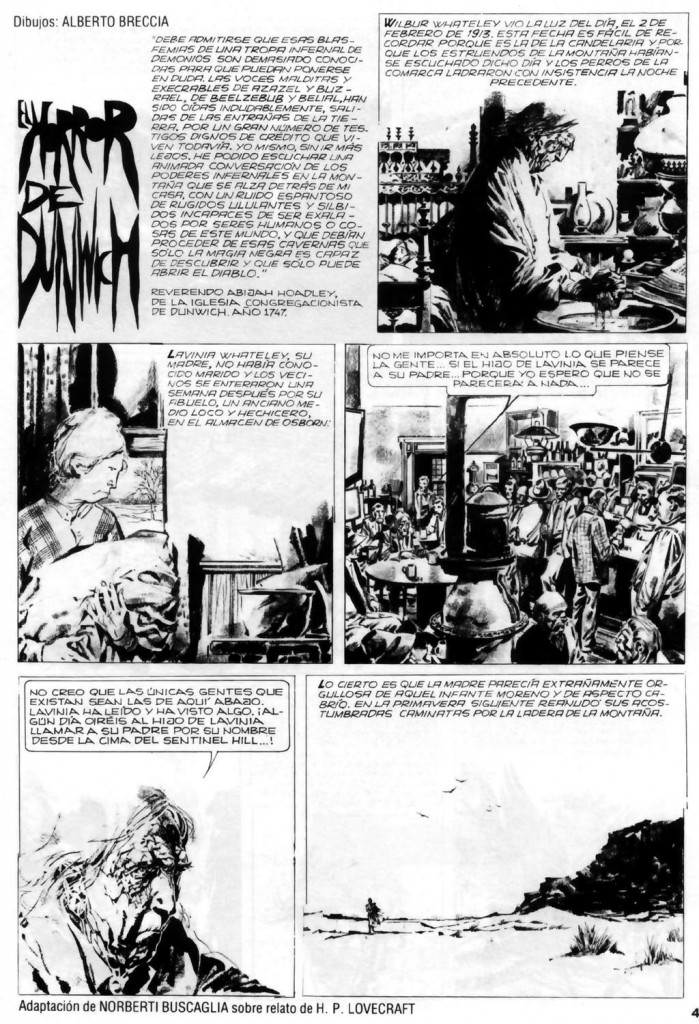

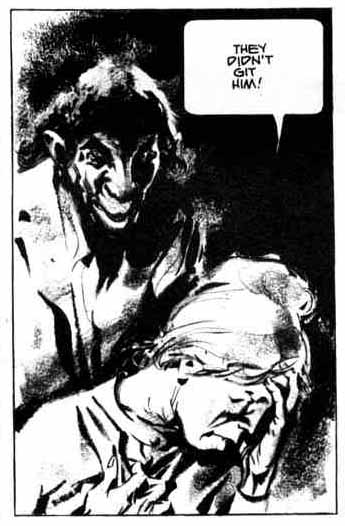

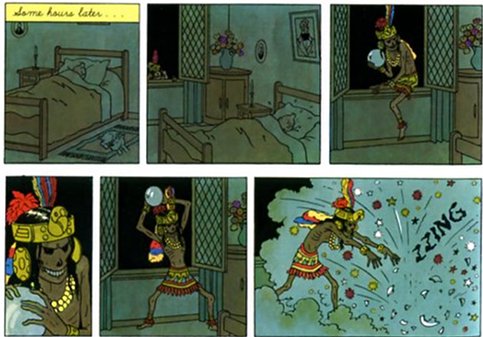

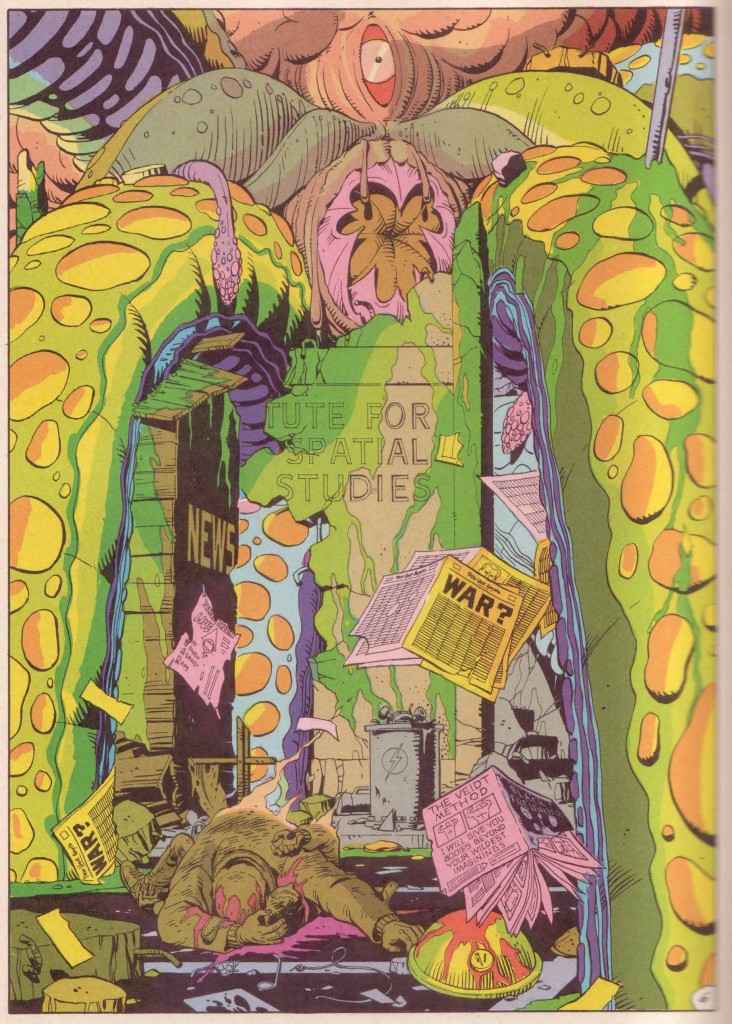

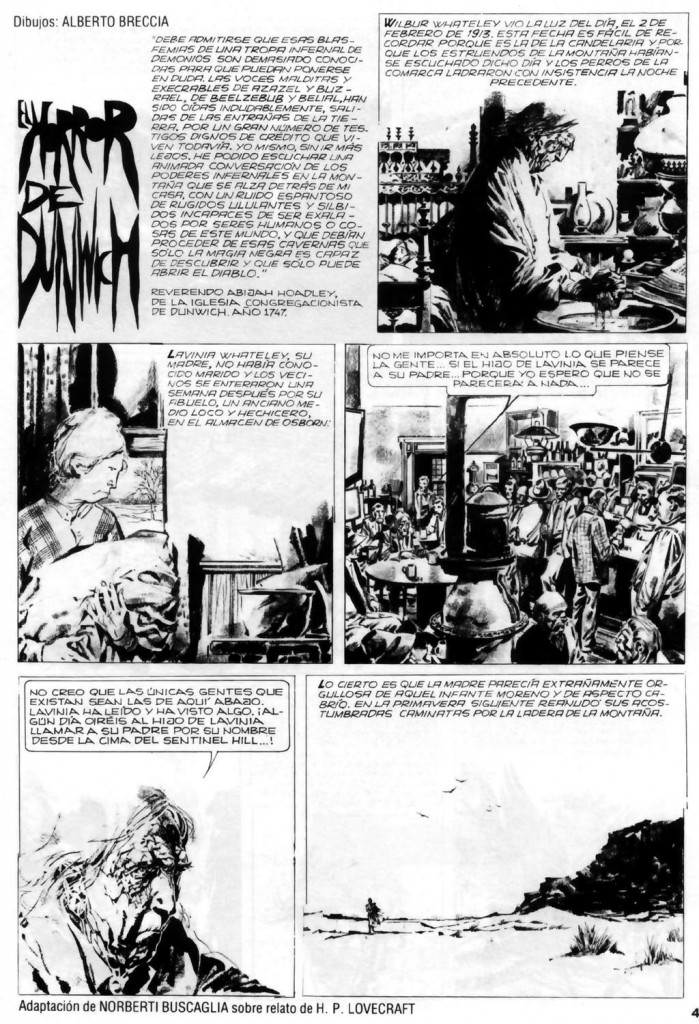

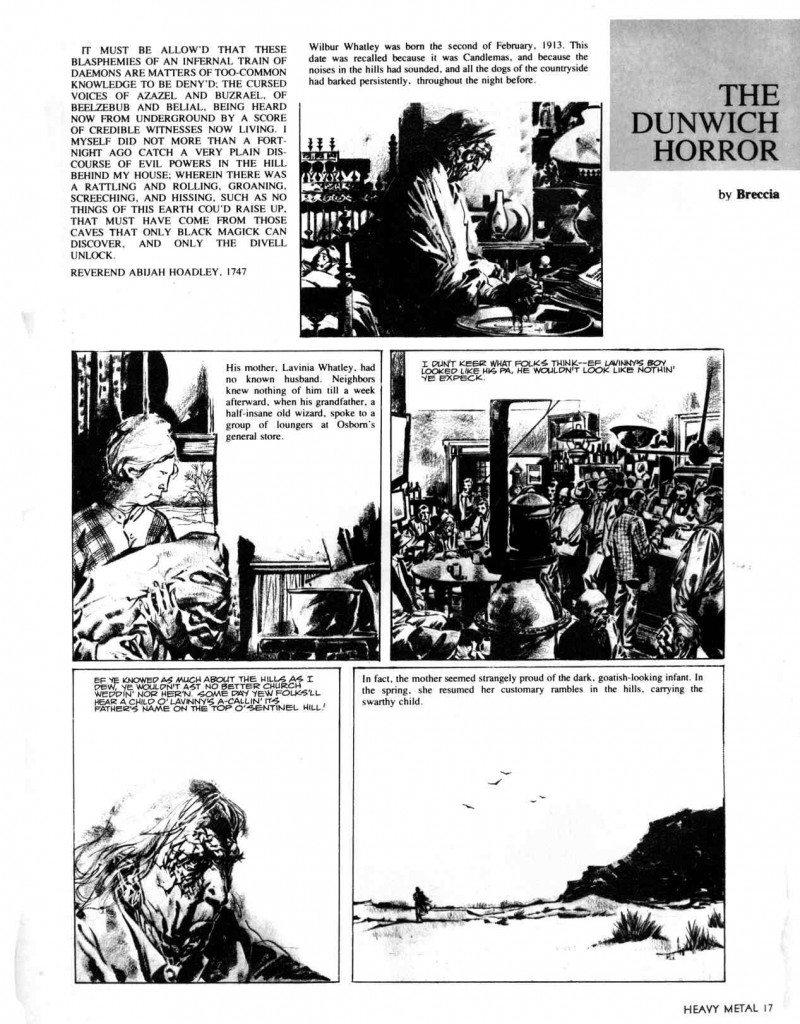

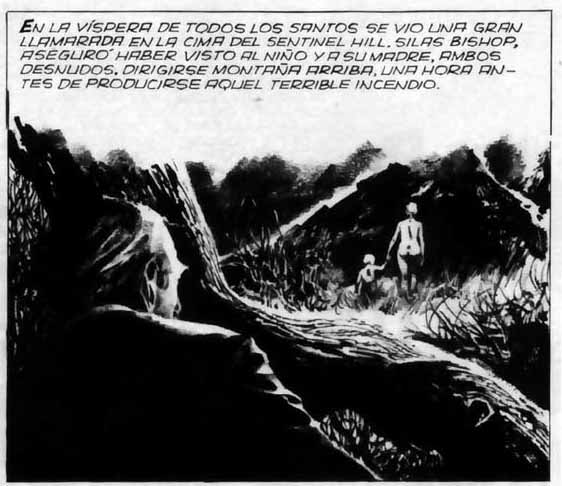

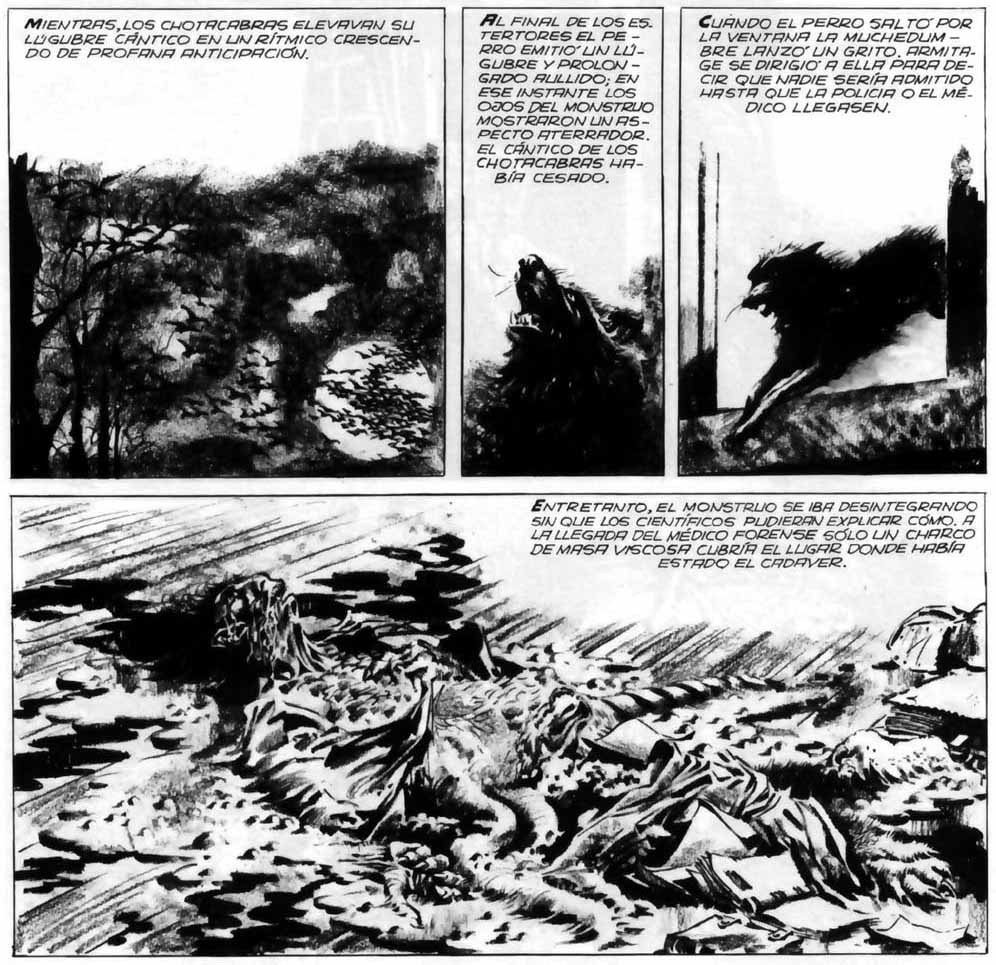

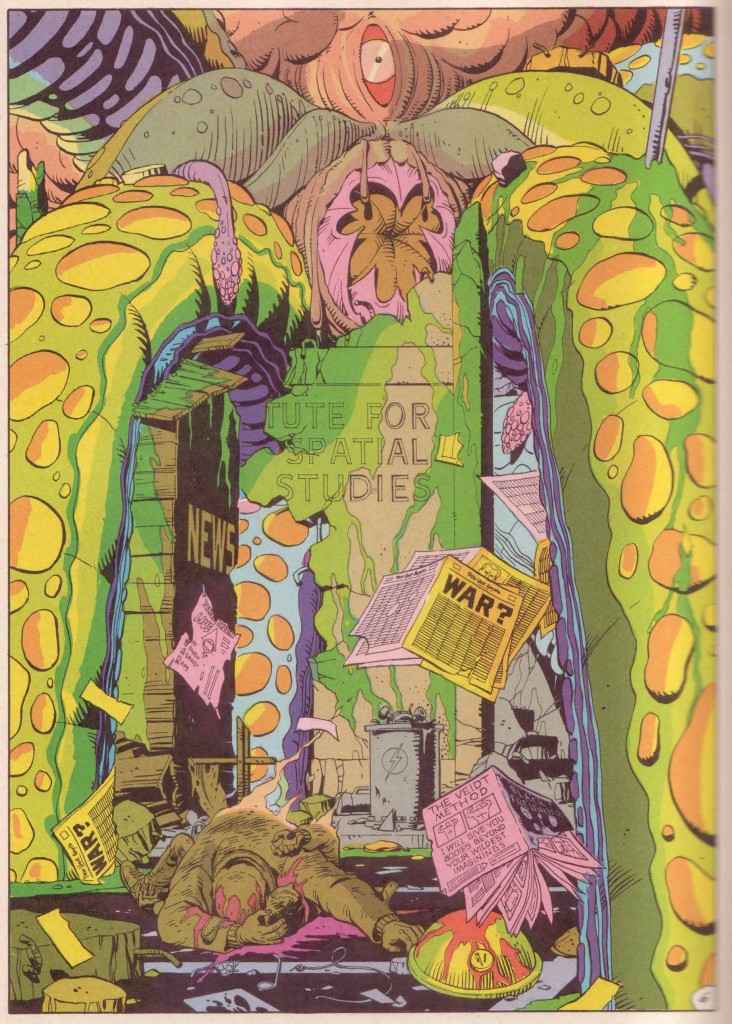

The adaptation of The Dunwich Horror by Norberti Buscaglia and Alberto Breccia is a more distinguished example which found its and first and only translation in the pages of the October 1979 issue of Heavy Metal. For the uninitiated or forgetful, the story concerns the mysterious and possibly inbred Whatley family; in particular the newly born, preternaturally intelligent child of unknown paternity, Wilbur Whatley, a veritable Baphomet. Ugly, wicked, and inhuman in anatomy, he is slain mid way through the narrative allowing investigations to begin under a certain Dr. Henry Armitage. Occult books are consulted and cryptograms decoded even as a mysterious force lays waste to the small town, slaying whole families in the thick of night. A final confrontation occurs on the hills of Dunwich where Wilbur’s monstrous twin brother is defeated and unmasked.

The presentation in the English language Heavy Metal is more than aptly named considering the debasements inflicted on it over the course of the production process.

[Spanish and English editions of The Dunwich Horror]

Yet even in the original, this seems to be a job approached with proficiency by Breccia rather than the excitement and innovation one finds in a work such as Rapport sur les aveugles (Breccia with Ernesto Sábato). Lovecraft’s slow meanderings (the delays, forebodings, and suspicions) don’t lend themselves well to the narrative ease found in comics adhering to classical forms. It must be said though this adaptation was probably never meant as a substitute for the original but as a sort of primer and graphic aide. It may be that even a moderately long short story of this ilk would probably need twice as many pages to achieve its desired effect. Examples of this watering down may be seen on every page. The secret rites practiced by mother and child seem strangely innocuous and are not followed by the ambiguity of a witness’ testimony that the child had:

“…some kind of a fringed belt and a pair of dark trunks or trousers on” and that “Wilbur was never subsequently seen alive and conscious without complete and tightly buttoned attire, the disarrangement of which…always seemed to fill him anger and alarm.”

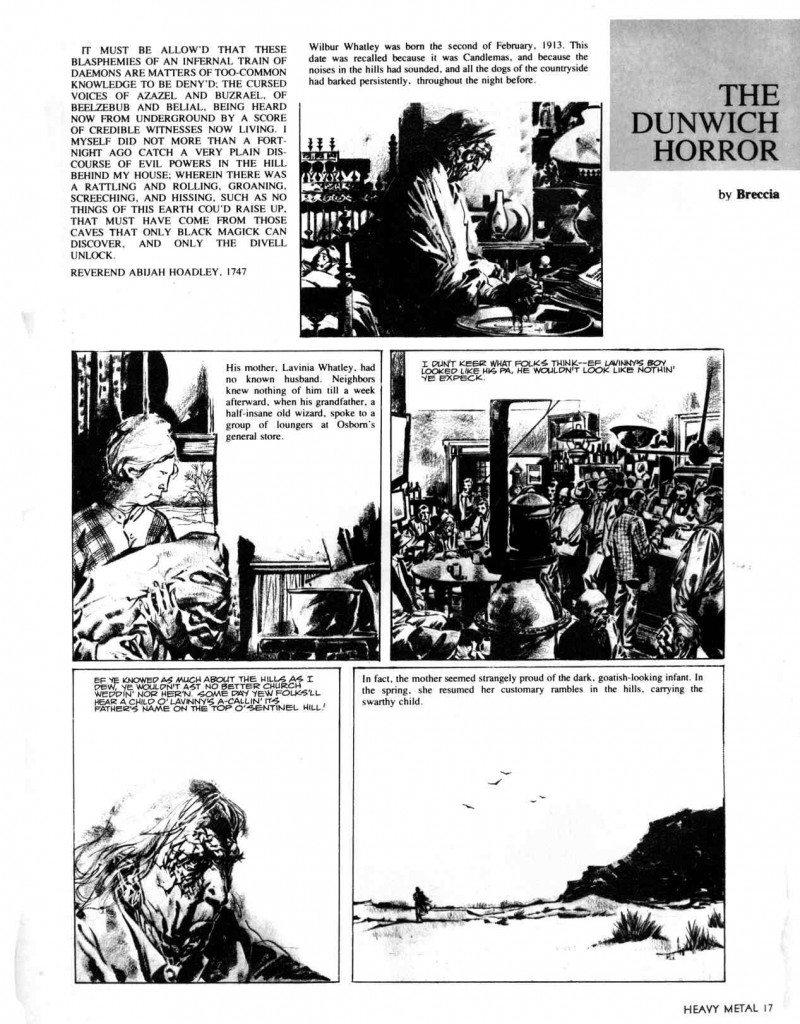

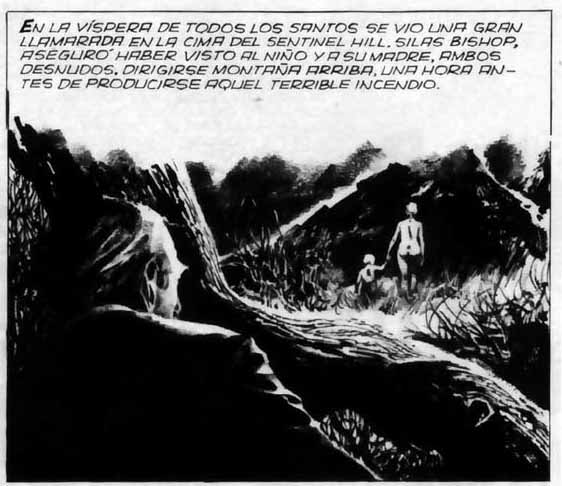

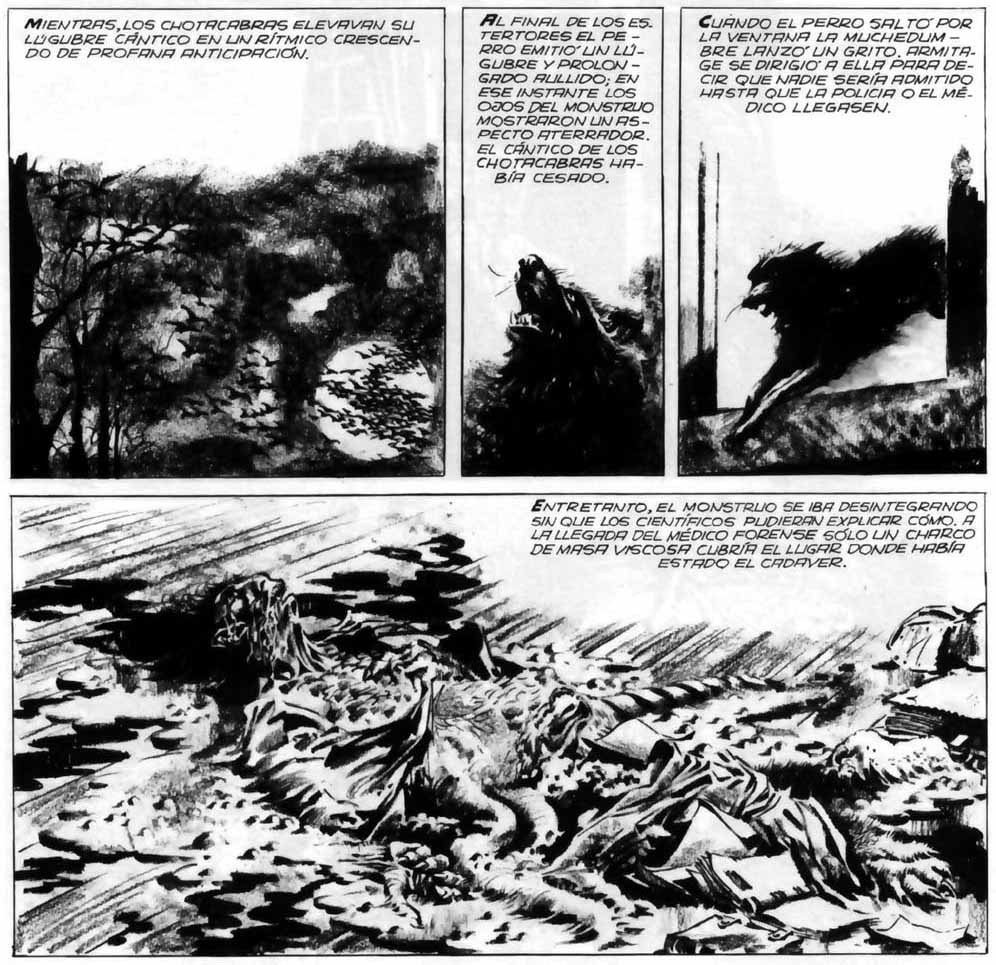

The occult sharings between grandfather and child found in the original are also omitted, these moments and their closeness suggesting not merely some demon spawn but unspoken incest and a deformed offspring (vehemently denied by Lovecraft as being too innocuous through his proxy Dr. Armitage), a parasite drawing knowledge and lifeforce from his grandfather who eventually dies by the child’s tenth year. Gone is that accumulation of fanciful and misanthropic detail: the cattle paid for in “gold pieces of extremely ancient date” which disappear (presumably consumed or sacrificed) at a prodigious rate; the town consumed by the ordinary rites of All-Hallow’s eve and Walpurgis Night; or the suggestion that “in 1917 [when] the war came…the local draft board….had hard work finding a quota of young Dunwich men fit even to be sent to development camp” and were “alarmed at such signs of wholesale regional decadence.” There are exceptions of course. The page and sequence showing the final dispostion of Wilbur Whatley is particularly excellent with its rough cut rabid cur and disintegrating form.

It occurs to me that almost all comic adaptations of Lovecraft seem to function best when seen more distinctly as illustration. The central panel on the third page of Buscaglia and Breccia’s adaptation works better than all three panels which follow it at showing Wilbur contempt for his mother, his overbearing presence like some evil Christ; the hills of Dunwich replacing that wedding at Cana and the messiah’s tarrying in the Temple in Jerusalem, an anti-Christ with altars on the high places. What better place to find a depiction of…

“…something almost goatish or animalistic”, “thick lips, large-pored, yellowish skin, coarse crinkly hair, and oddly elongated ears”

….or the corpse of Wilbur Whatley with skin “thickly covered with coarse black fur, and from the abdomen a score of long greenish-grey tentacles with red sucking mouths protruded limply” —

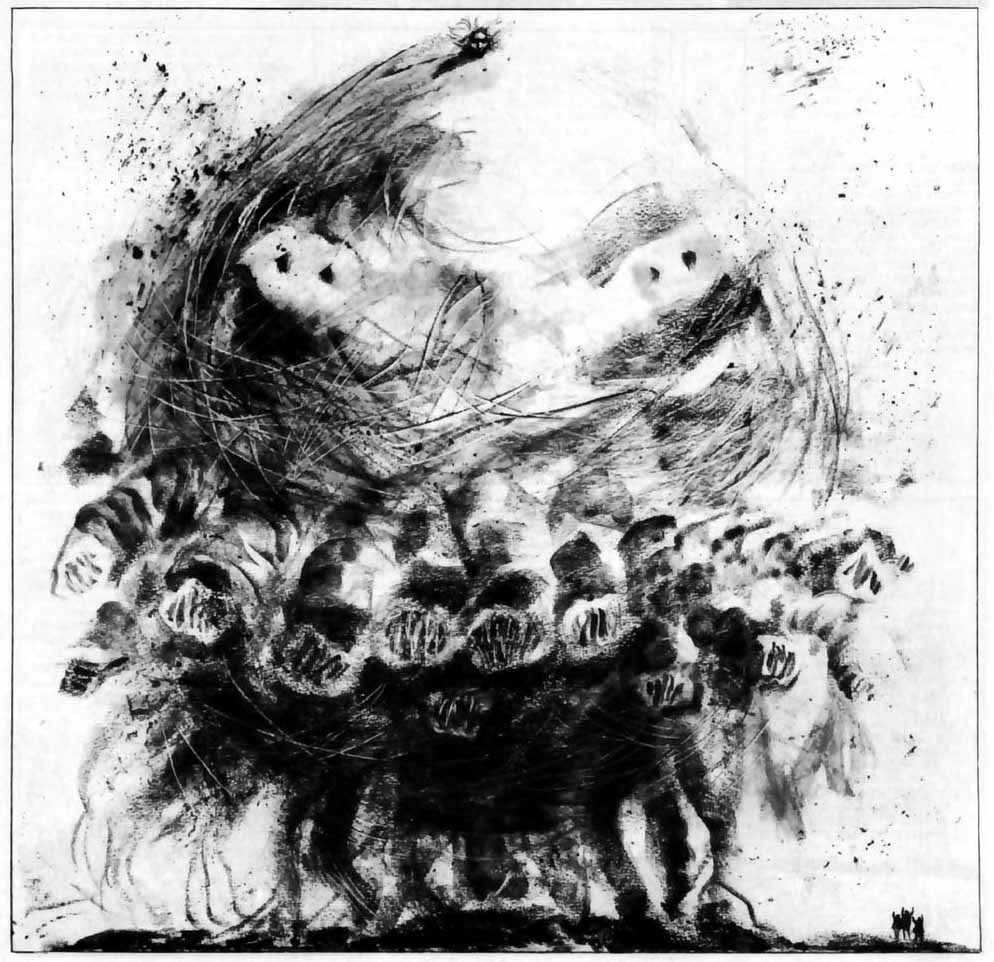

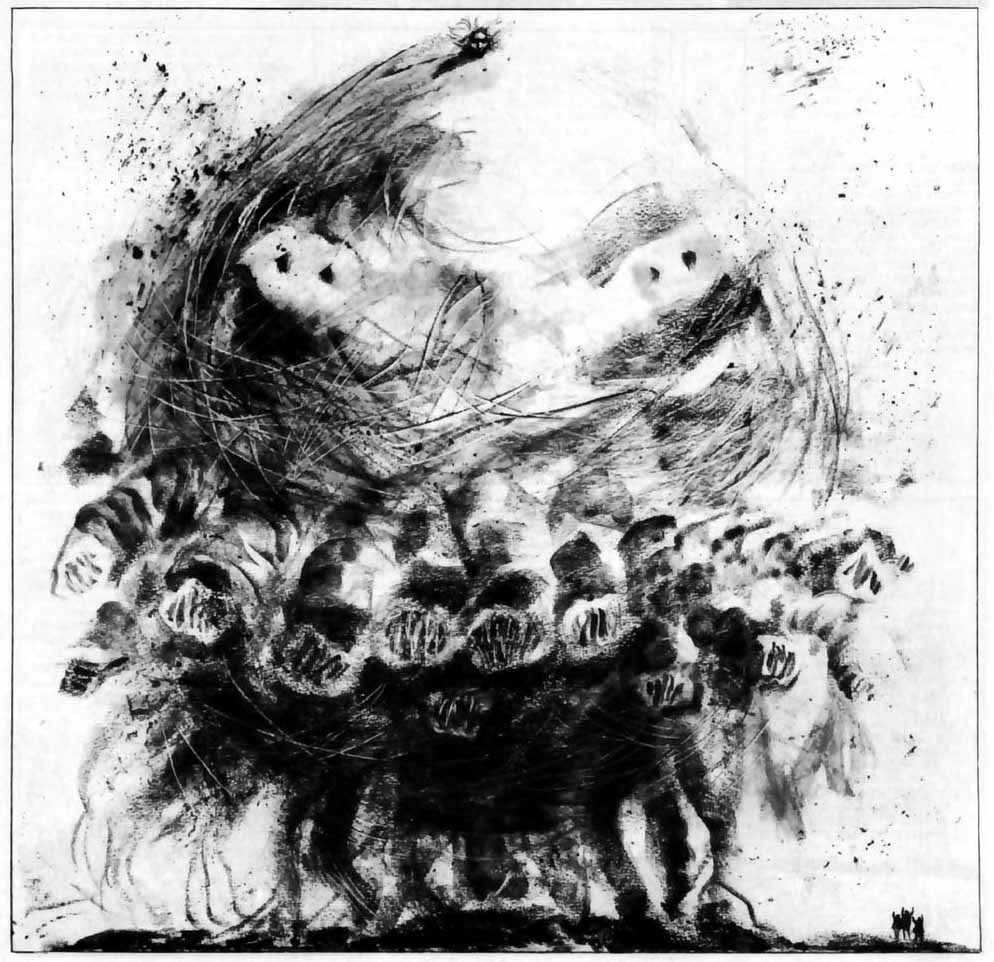

…or that final epiphany on the hills of Dunwich.

a “grey cloud – a cloud about the size of a moderately large building…Bigger’n a barn… all made o’ squirmin’ ropes… hull thing sort o’ shaped like a hen’s egg bigger’n anything with dozens o’ legs like hogs-heads that haff shut up when they step… nothin’ solid abaout it – all like jelly, an’ made o’ sep’rit wrigglin’ ropes pushed clost together… great bulgin’ eyes all over it… ten or twenty maouths or trunks a-stickin’ aout all along the sides, big as stove-pipes an all a-tossin’ an openin’ an’ shuttin’… all grey, with kinder blue or purple rings… an’ Gawd it Heaven – that haff face on top…’

Artful homage remains Lovecraft greatest legacy to comics, its practitioners like the aesthetes in The Call of Cthulhu, dreaming dreams and drawing monsters conceived of decades before. From that point of view, the Lovecraft issue of Heavy Metal was only making a point explicit for images from Lovecraft have ever been the center of one of the founders of that magazine, namely Philippe Druillet.

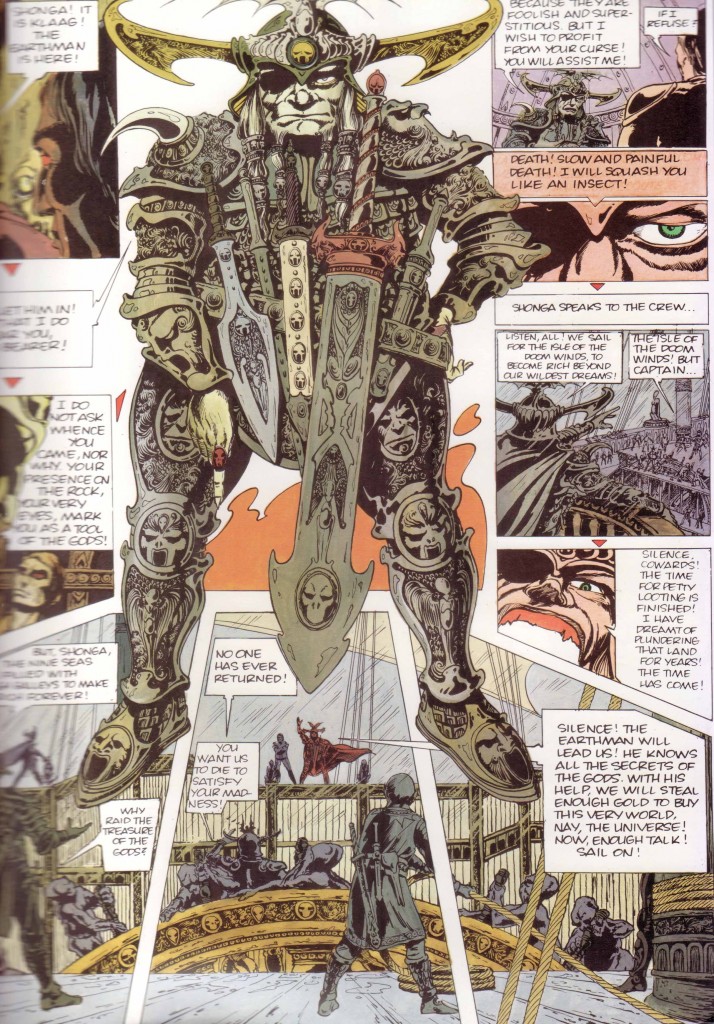

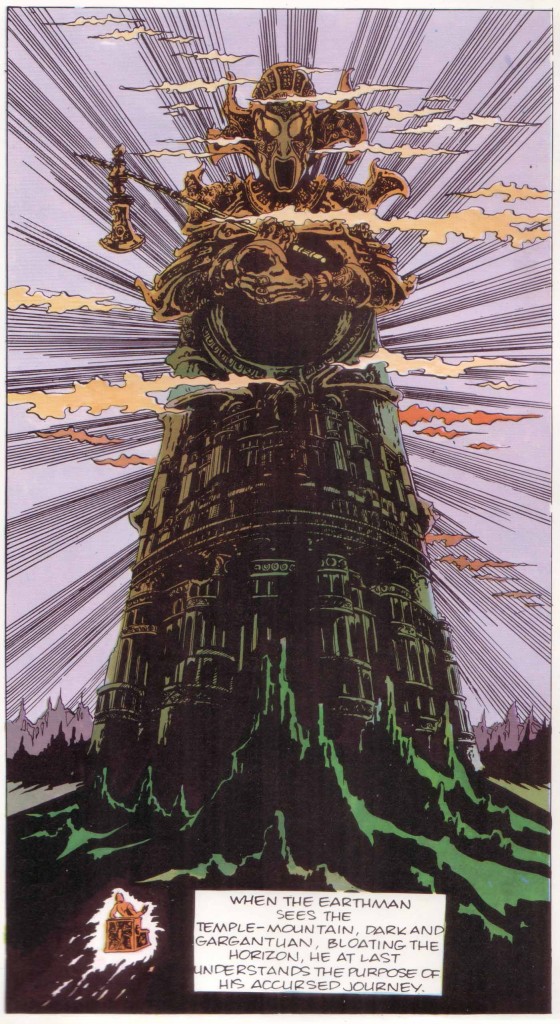

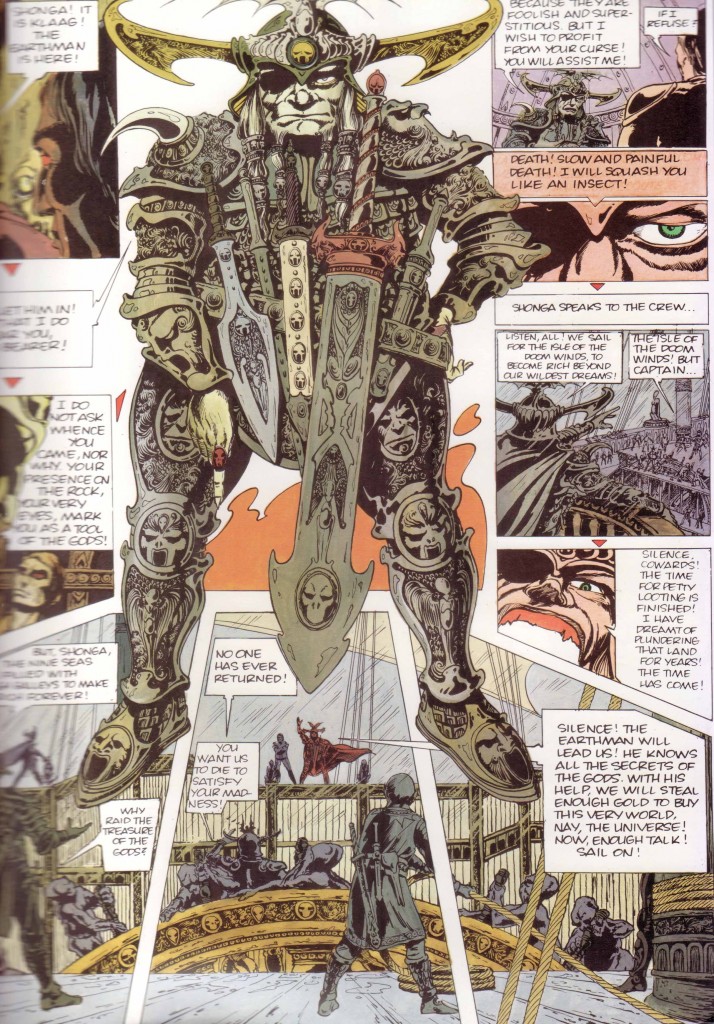

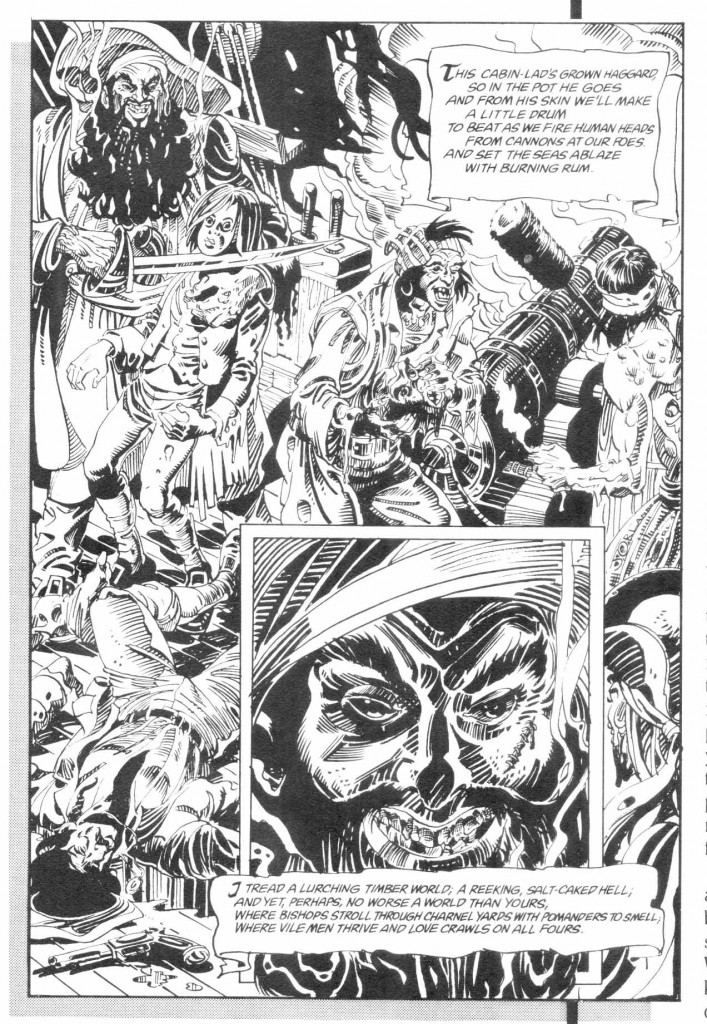

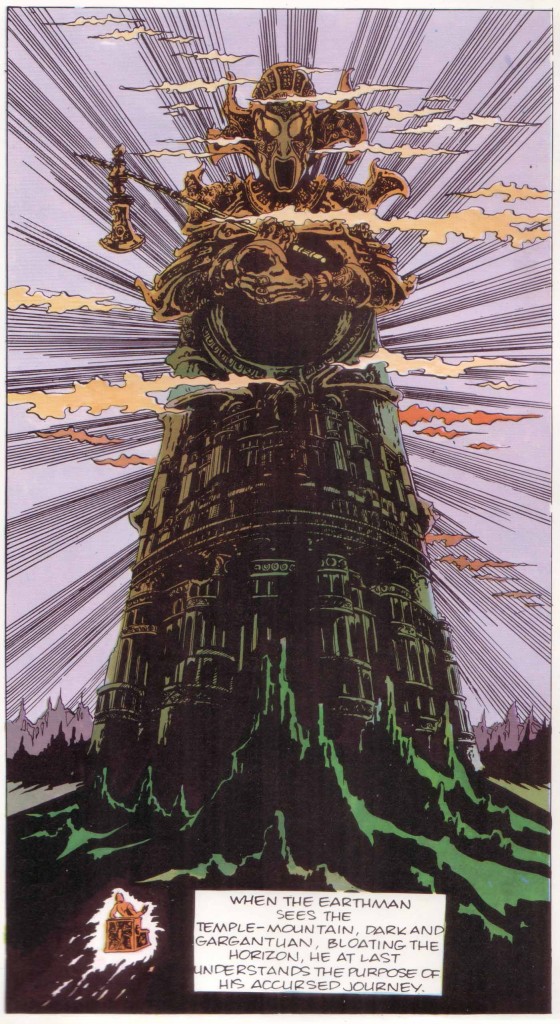

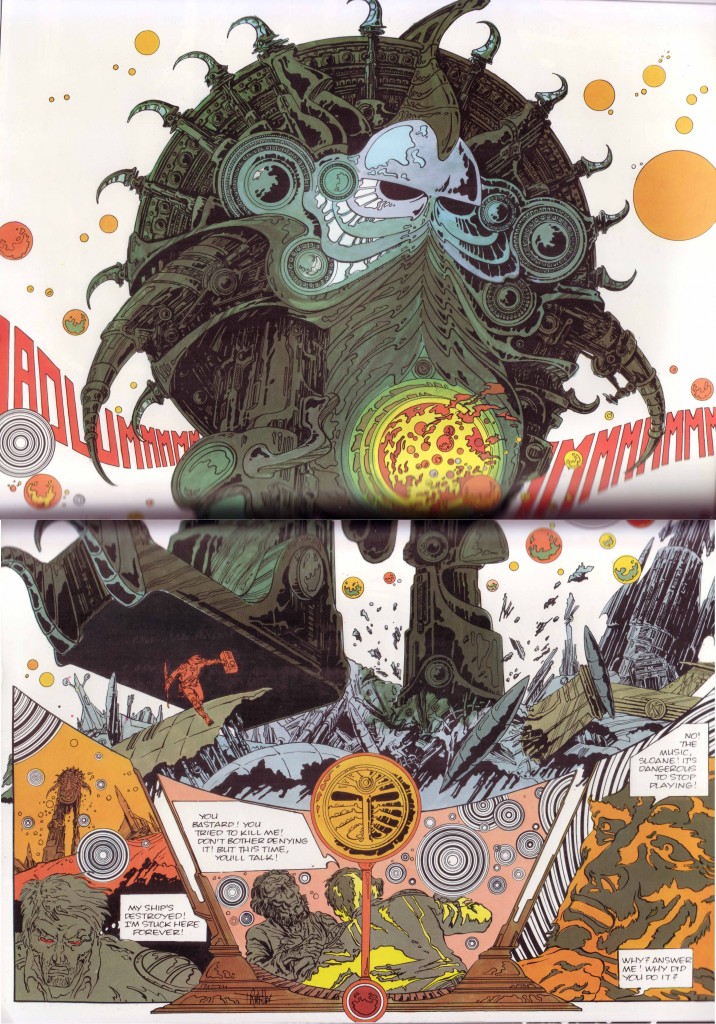

The 6 Voyages of Lone Sloane is an adaptation by any other name but here transferred to the vast emptiness of space and incalculable eons, not unlike his space faring version of Wagner’s Ring Cycle. The stories are largely nonsensical but intermittently involve forgotten fairways, secret words of power, cultic allegiances, and old dark gods—not just a testament to Druillet’s limitations as a writer, but also his singular focus on the sense of wonder and awe one finds in Lovecraft’s stories. As China Miéville writes in his introduction to At the Mountains of Madness:

“H. P. Lovecraft is the towering genius among those writers of fantastic fiction for whom plot is simply not the point.”

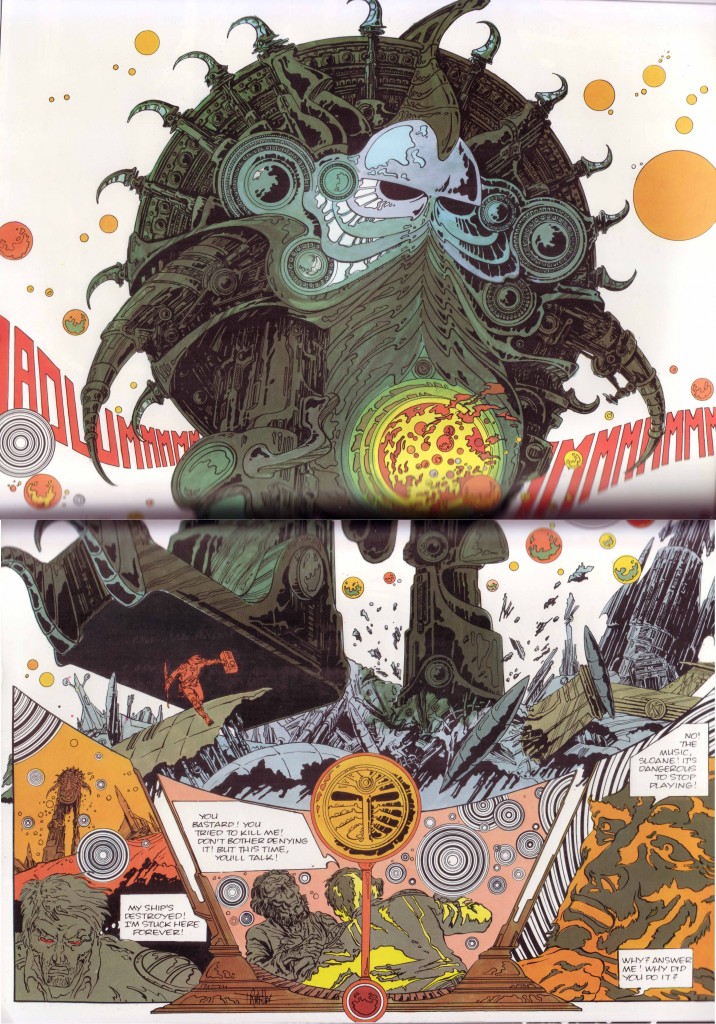

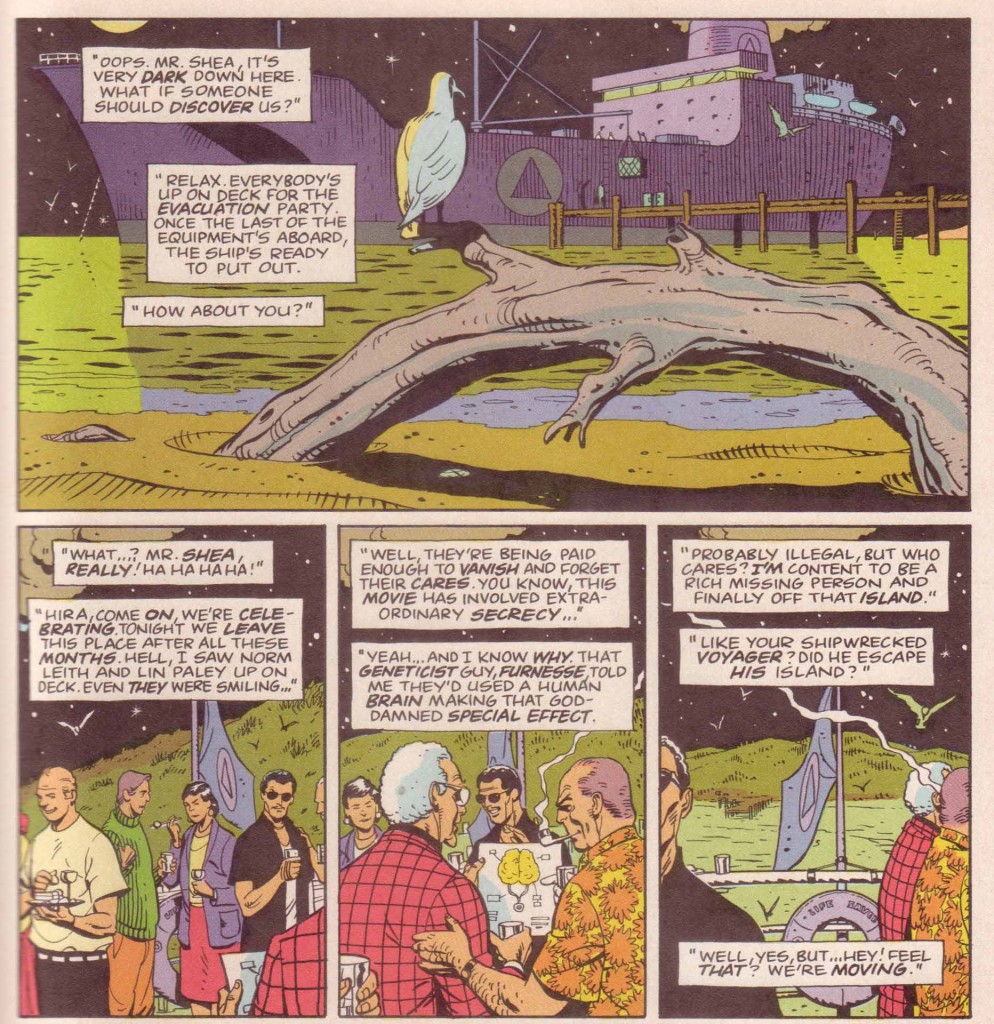

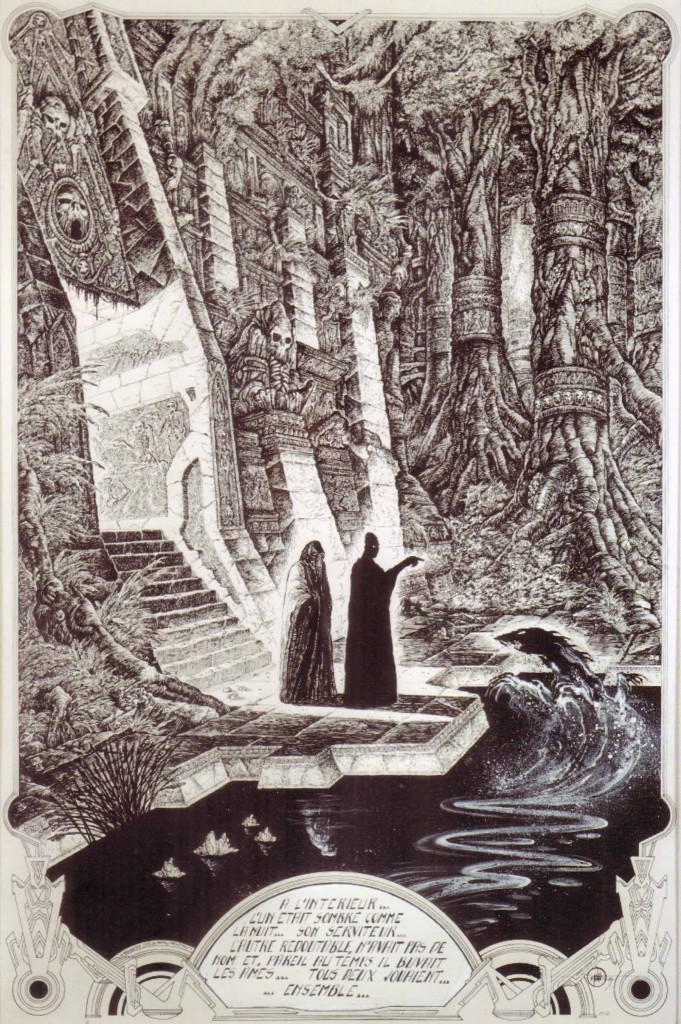

The imagery here is redolent of the third part of The Call of Cthulhu (“The Madness from the Sea”) in which the crew of the Emma lands on an unknown island, the “nightmare corpse-city of R’lyeh” and encounter Cthulhu himself. In not quite the same words and at various points in Druillet’s anthology of tales, we see the pirate ship Alert with its “queer and evil-looking crew of Kanakas and half-castes”…

[Images from Lone Sloane by Druillet and Watchmen by Joe Orlando]

…and then

“a coastline of mingled mud, ooze, and weedy Cyclopean masonry which can be nothing less than the tangible substance of earth’s supreme terror — the nightmare corpse-city of R’lyeh, that was built in measureless aeons behind history by the vast, loathsome shapes that seeped down from the dark stars” …where ” the hideous monolith-crowned citadel whereon great Cthulhu was buried, actually emerged from the waters.”

…before apprehending the very image of Cthulhu himself—mechanical, rampaging, and yet curiously driven away by music.

No other cartooning acolyte of Lovecraft has delineated the author’s Cyclopean landscapes quite as effectively as Druillet, an artist who has yet to show any devotion to moderation, logic or good sense to this day.

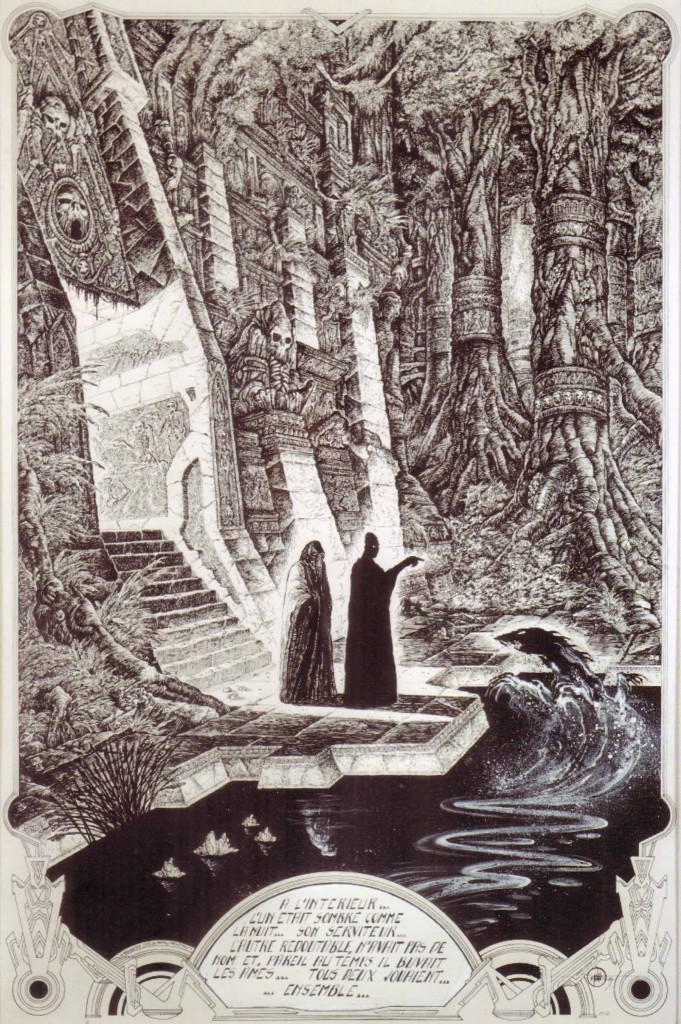

[Gail, Philippe Druillet]

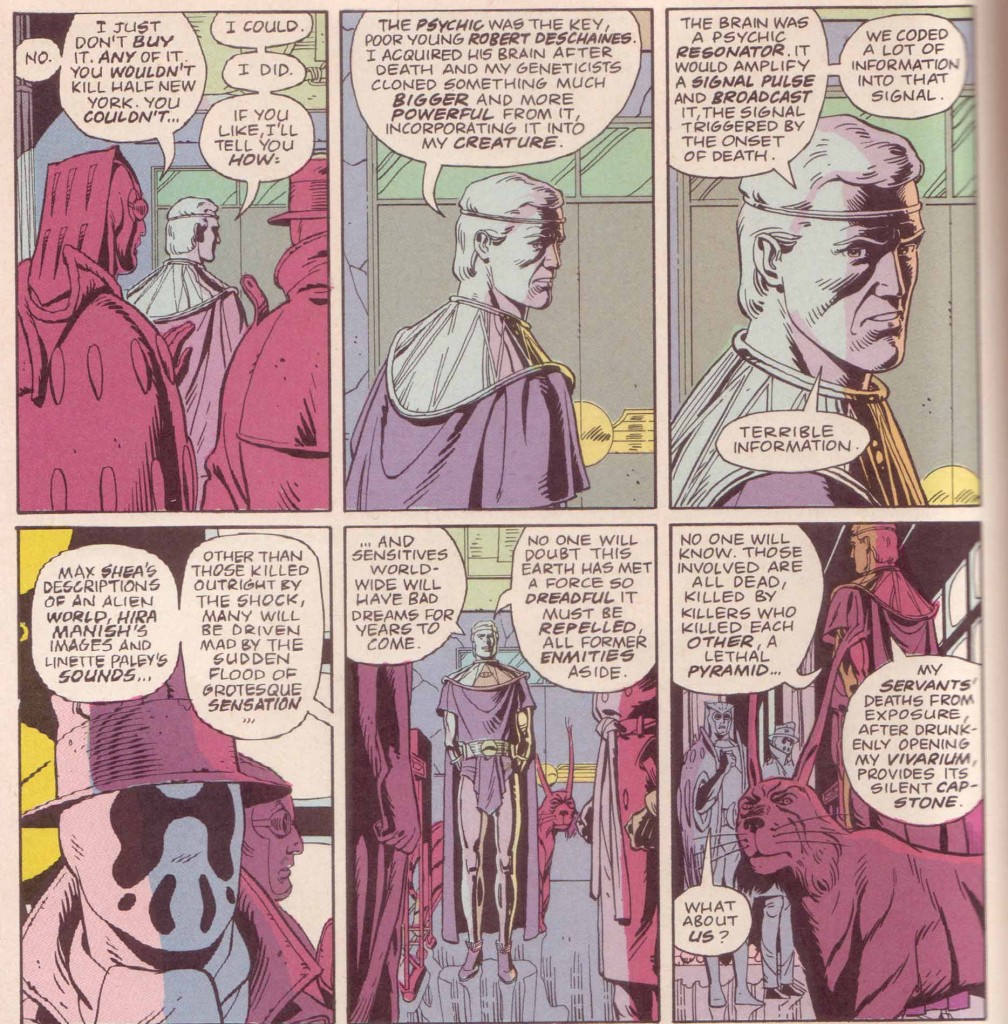

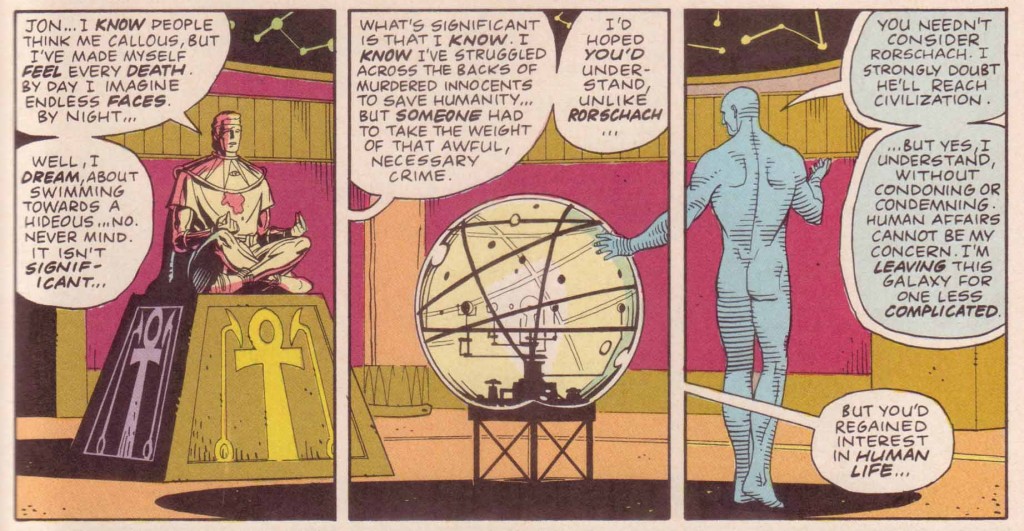

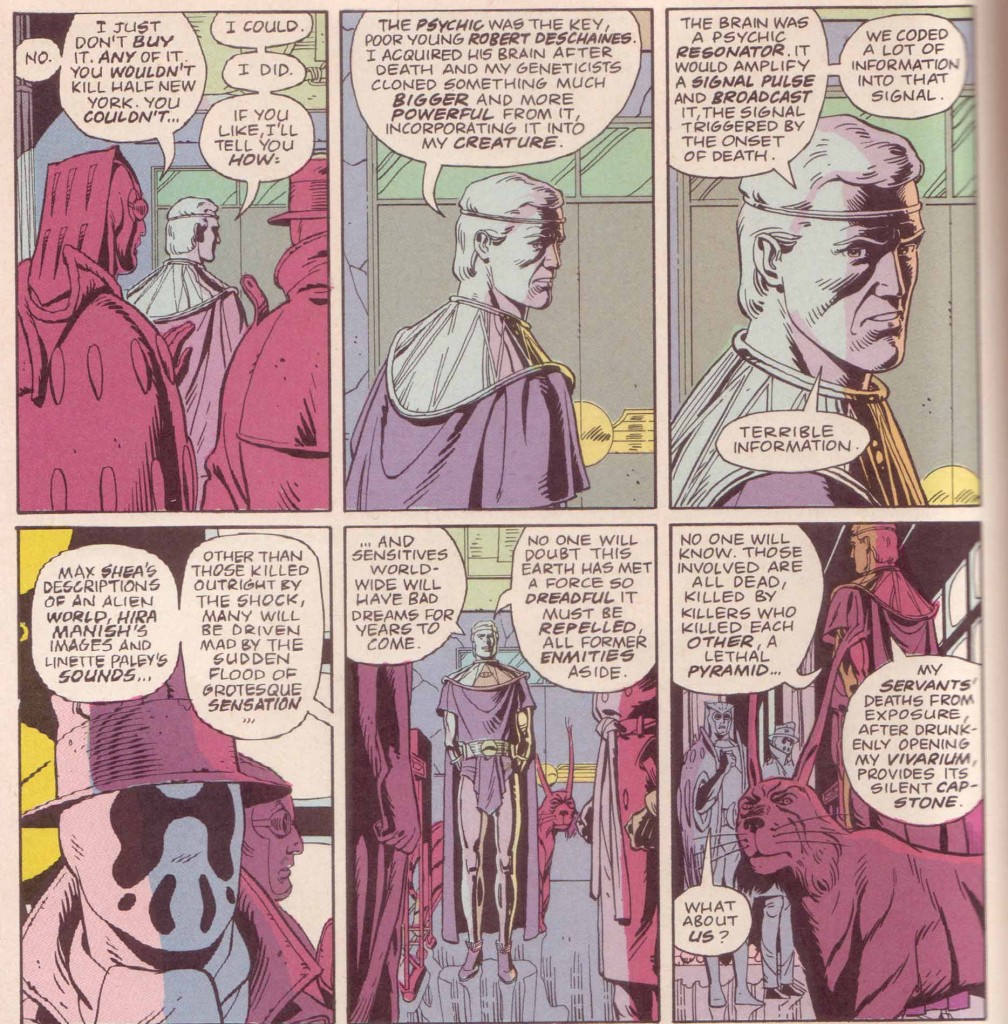

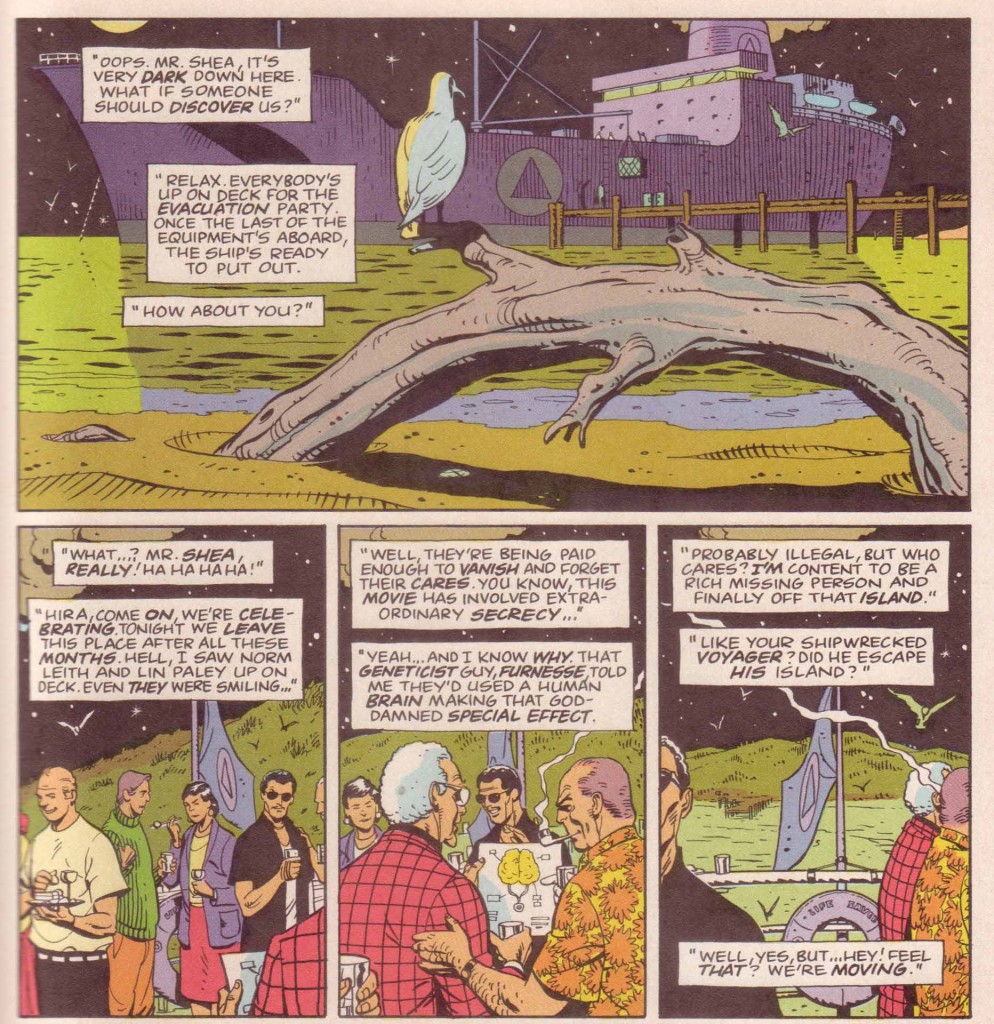

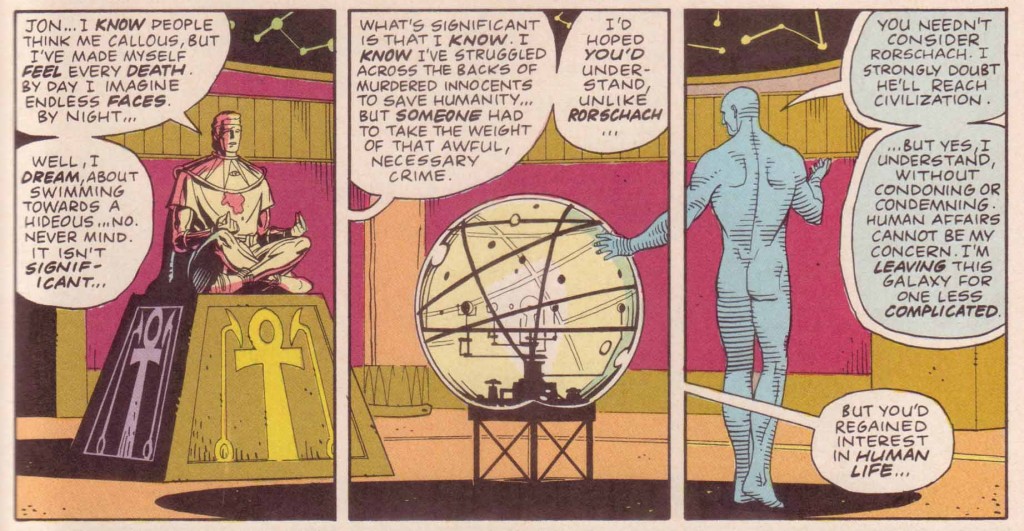

Beyond this point, there is the total assimilation of Lovecraft’s innards by Alan Moore, a comic literary criticism not unlike Martin Rowson’s adaptation of The Life and Opinions of Tristam Shandy, Gentleman. Lovecraft’s madness is resolved to science in Watchmen, the stories distilled to a metaphor for creation itself. Ozymandias’ monster is the product of literature, art, and sound, a psychic wave from the future if not an alternate dimension; driving “sensitives” to distraction or outright insanity; its god-curators slaughtered and forgotten; perhaps an “origin story” for Lovecraft himself.

“It was from the artists and poets that the pertinent answers came, and I know that panic would have broken loose had they been able to compare notes…These responses from esthetes told disturbing tale. From February 28 to April 2 a large proportion of them had dreamed very bizarre things, the intensity of the dreams being immeasurably the stronger during the period of the sculptor’s delirium. Over a fourth of those who reported anything, reported scenes and half-sounds not unlike those which Wilcox had described; and some of the dreamers confessed acute fear of the gigantic nameless thing visible toward the last.” (The Call of Cthulhu)

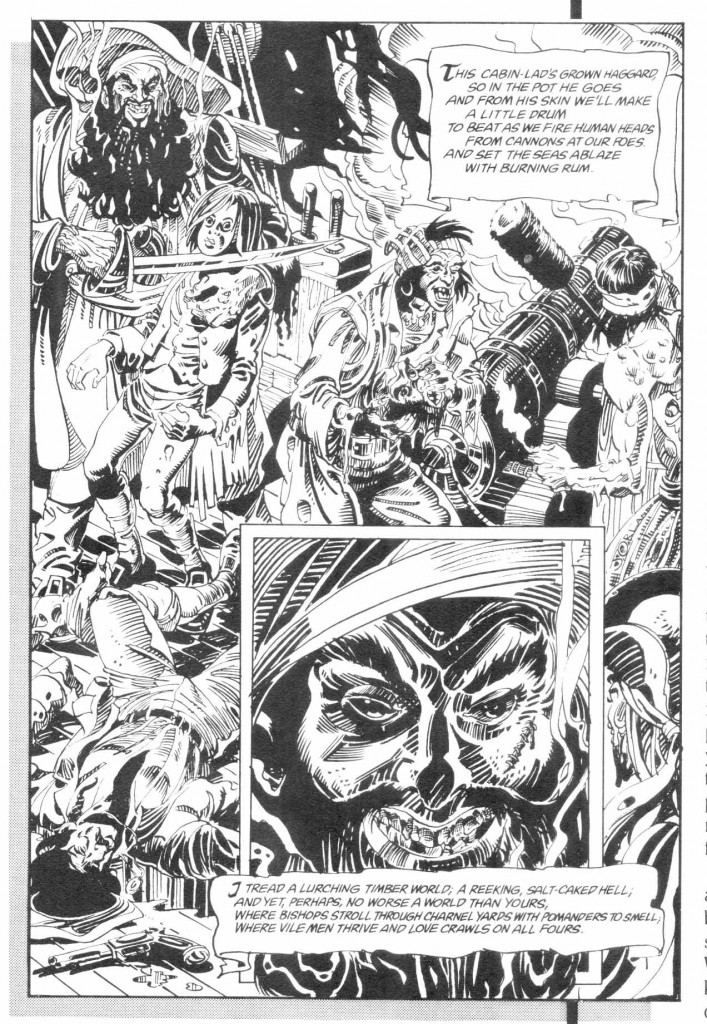

Scattered throughout are the pirates beckoning from penny comics, the surfeit of voyages by ship, the mysterious island of genesis, the incipient insanity and death.

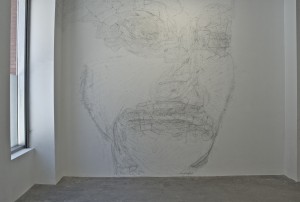

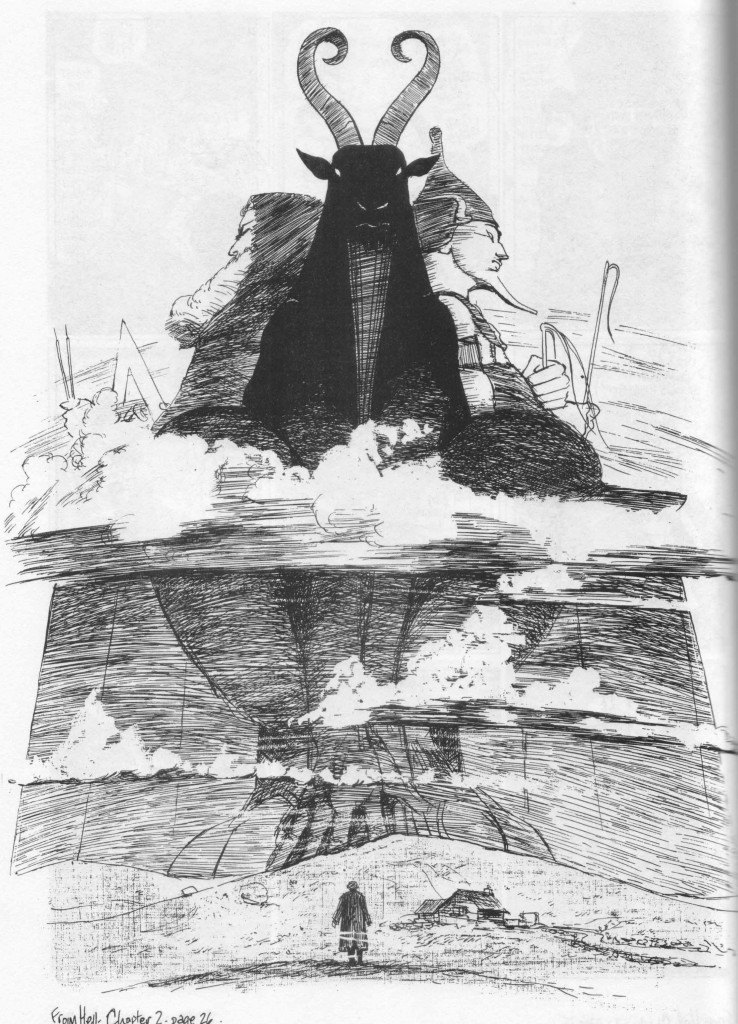

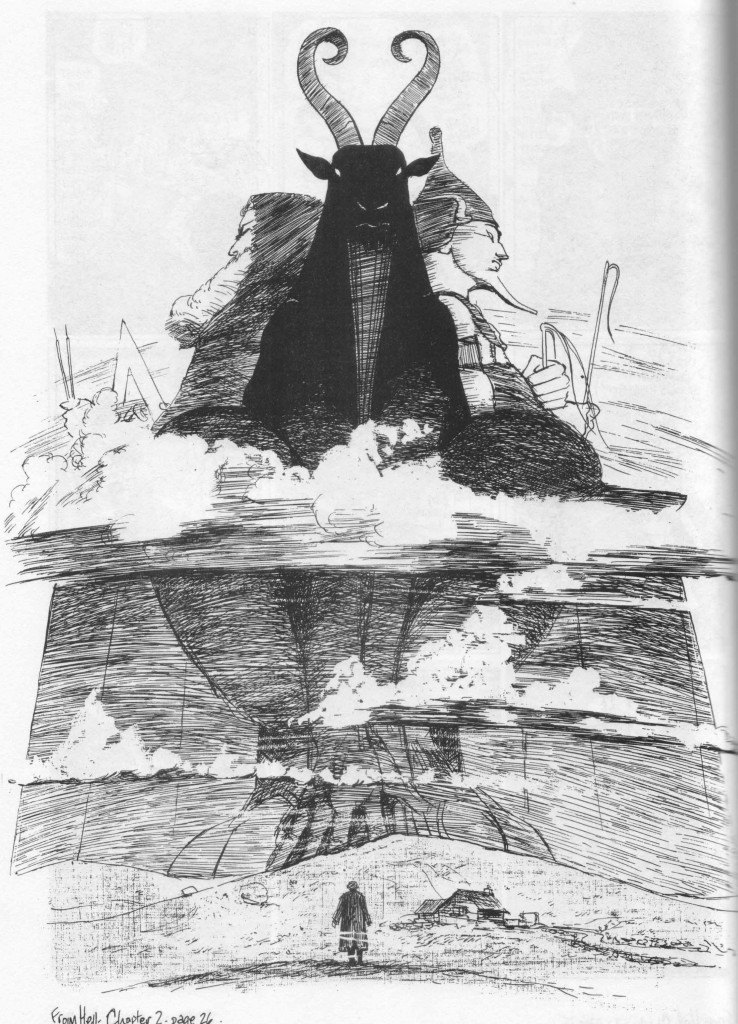

At other times, Moore’s concept of worship becomes less rational and reverts to the high places.

[From Hell, Eddie Campbell]

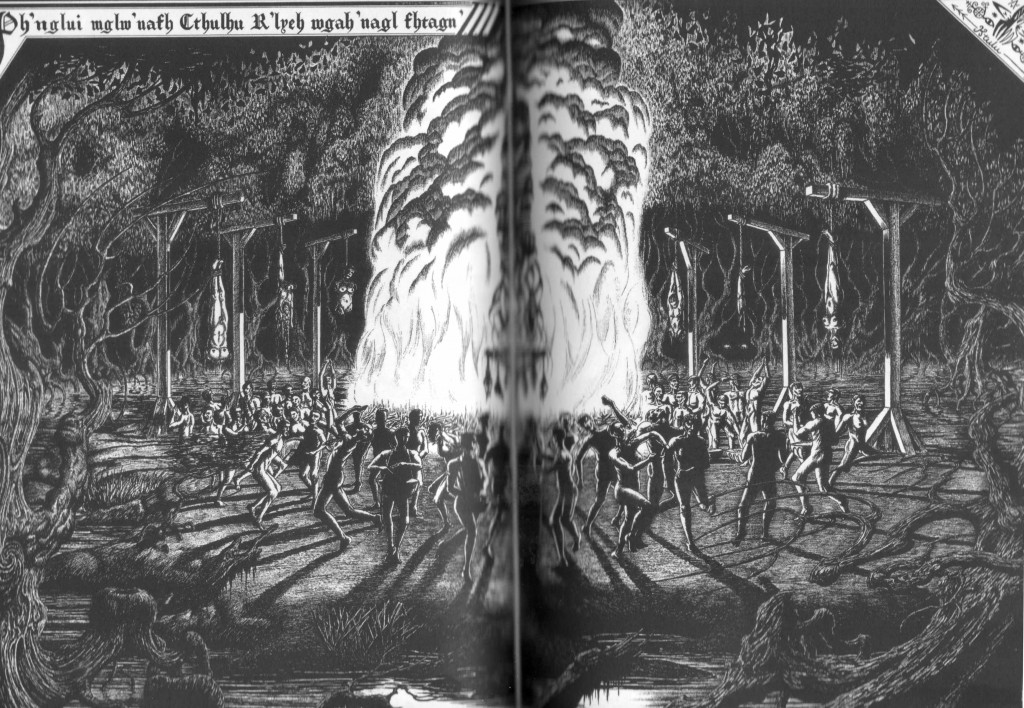

This literary dissection of Lovecraft is played out in earnest in both The Courtyard and Neonomicon, the latter’s title hinting at Moore’s own penchant to see beneath the surface to the genital horror, the unspoken orgies, and the seasoned racism of Lovecraft. Concerning the latter and the members of a New Orleans cult (shot like dogs in The Call of Cthulhu the better to control them) Lovecraft writes:

“…the prisoners all proved to be men of a very low, mixed-blooded, and mentally aberrant type. Most were seamen, and a sprinkling of Negroes and mulattoes, largely West Indians or Brava Portuguese from the Cape Verde Islands, gave a colouring of voodooism to the heterogeneous cult. But before many questions were asked, it became manifest that something far deeper and older than Negro fetishism was involved. Degraded and ignorant as they were, the creatures held with surprising consistency to the central idea of their loathsome faith.”

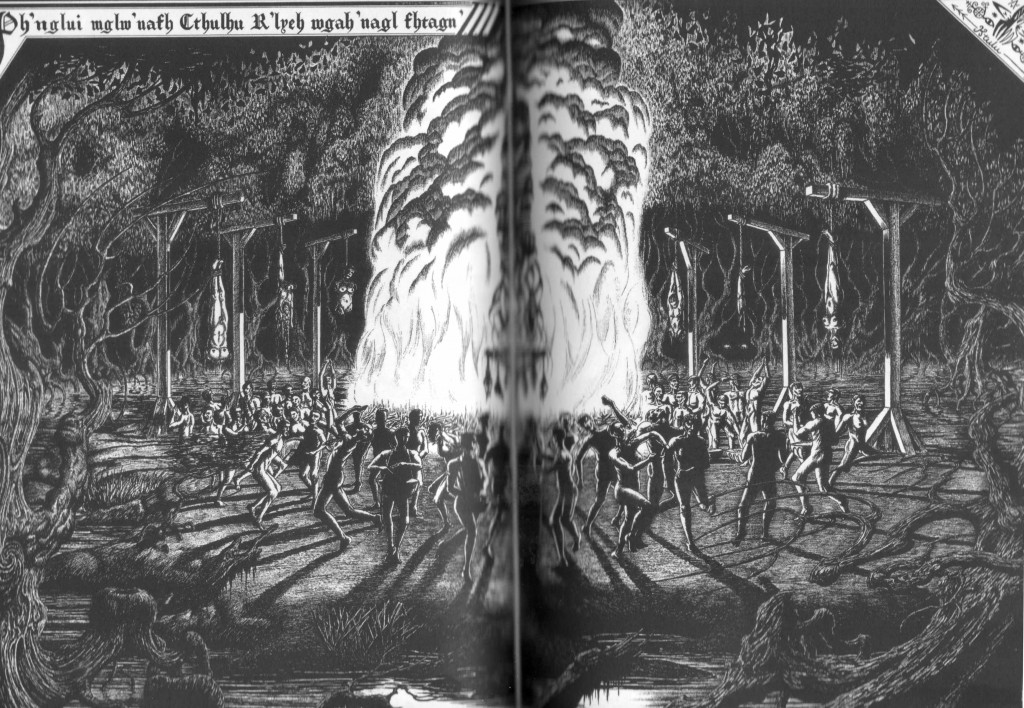

[from The Call of Cthulhu by John Coulthart]

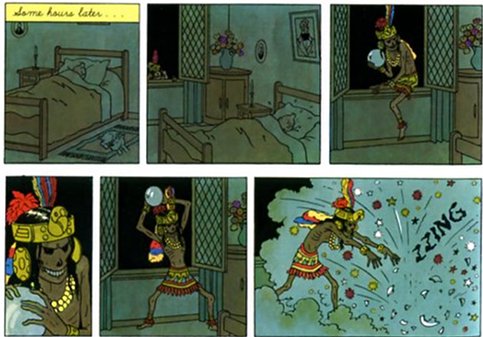

These words finds their counterpart in the works of Herge and the Inca mummy in The Seven Crystal Balls of which Noah Berlatsky once wrote:

“This, then, is really a case where I don’t like the sequence despite its racism and imperialism. As far as I can tell, I like it because of them. The fascination/repulsion Herge feels towards the strange gods of colonized cultures generates real creative frisson. Which makes me wonder if maybe that’s true of racism and stereotypes in general. It seems like, beyond their other uses, they sometimes have an appeal which might be called aesthetic. A certain amount of cultural creativity goes into shaping the person in front of you into a phantom monstrosity, and that creativity can itself be exciting and fascinating. The dream’s appeal is its vividly imagined ugliness; the exhilaration of imposing on the world the gothic products of one’s skull.”

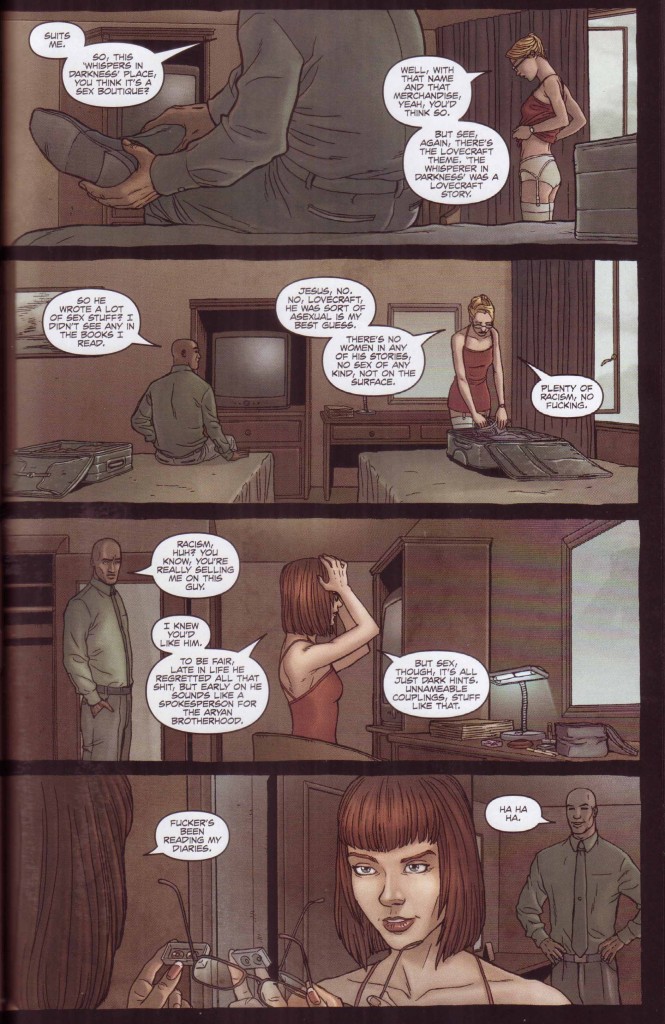

Moore’s reversal of Lovecraft’s xenophobia is patent in Neonomicon, a Lovecraft homage so thick with references that it probably demands a companion book (see The Courtyard Companion and an extensive discussion at Comics Comics). Like the tales which inspired it, the plot is all investigation, exposition, and interrogation. The art by Jacen Burrows is strangely cartoonish like a point and click video game adventure or a Saturday morning cartoon; which may seem strangely serendipitous to some, that coyness being a subset of Lovecraft’s own dread of sexual description.

The main protagonists are two FBI agents named Merril Brears (white, female sex addict) and Gordon Lamper (black male, conspicuously “normal”), the object of their investigation a cult invested in the Old Ones. The Dagon worshippers might as well be gentrified East Village baby boomers, almost everyone white as a sheet and sagging with years of excess, the new Satanism, an antidote to the privileged old biddies lacing Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby. Where Lovecraft frequently took care to situate his cultists in distant habitations in deference to their paganism (from the Latin paganus meaning villager or country-dweller), Moore opts for the new heathens in their old squats. The only African Americans in Moore’s comic are investigating officers, a reversal of their position in Lovecraft’s stories where they are invariably abominations.

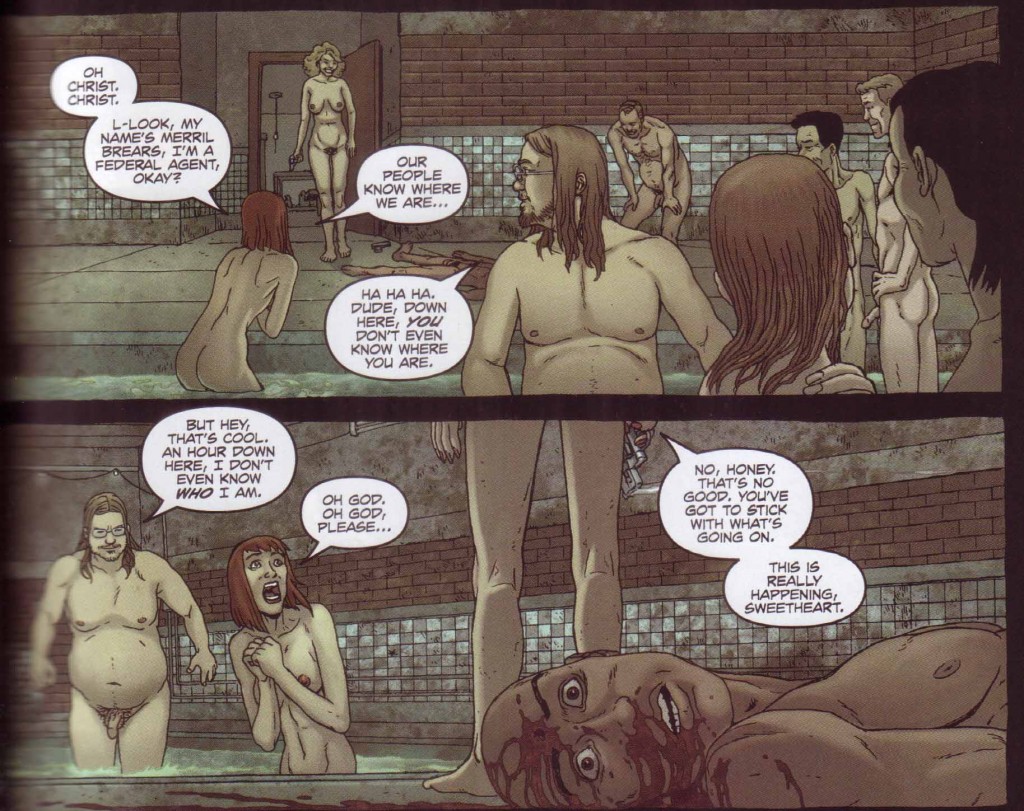

In chapter 2 of the comic (“The Shadow Out of America”), Merril strips and literally dresses like a whore in front of her black partner, all this without the slightest sexual arousal on both their parts, a counterpoint to a conversation about the “asexual” nature of H.P. Lovecraft. Gordon is duly shot and necrophilically abused once he is brought into the orgone-filled sanctum of the nearly racially exemplary cultists (the group includes an Oriental couple; a nod to the Chinamen and “unclassified slant-eyed folk” so beloved of Lovecraft ). Moore has never been shy about heavy-handed symbolism.

It is of course, stressed repeatedly that Merril is a recovering sex addict. Yet she resists her partner in a kind of temperance aided by racial purity; a chastity which repudiates miscegenation and hides from the conception of “foreign mongrels” (see The Call of Cthulhu). Far better to be coupled to a demon god for that is exactly what happens at the close of that chapter where Merril is raped repeatedly by Dagon—thus a latter day Lavinia Whatley of Dunwich who will bear the incarnation or avatar of Cthulhu. The protagonist of The Shadow over Innsmouth is of course repulsed both visually and olfactorily by the presence of innumerable half-breeds in that town; his fear of contamination realized in full at the tale’s denouement when he discovers his own mixed heritage (he is of the Deep Ones). [1]

* * *

“It represented a monster of vaguely anthropoid outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind.”

If genre is a multi-tentacled monster with a gaping vaginal maw then no one should be surprised at the mucoid sheen of Alan Moore’s countenance. These comics are concentrated deconstructions of everything treading gently on the surface of Lovecraft’s stories, far more interested in evil than mirth; a fact which separates them from metatextural films like Drew Goddard and Joss Whedon’s The Cabin in the Woods.

That film has been self-described as a loving hate letter to horror movies and a rejection of the torture porn industry. The saviors in Cabin are the classics of the genre—werewolves, zombies, marionettes, the works of Clive Barker and Stephen King et al.—once locked in a labyrinthine glass walled prison like the Minotaur but then loosed upon benighted entertainment industry moguls to the violent cathartic delight of most of the audience. Beneath that cabin and entertainment complex lies an old god destined to destroy the world and the human race. Strange then that this jocular criticism fails so completely in conveying (perhaps intentionally) any of the unease and trepidation which those idolized exemplars so hoped to challenge their audiences with. Horror for Goddard and Whedon would appear to be a place of solace and entertainment not fear, dread, and revulsion. They remain quite unconvinced by that which they write. Not for them is Lovecraft’s suggestion that:

“The one test of the really weird is simply this — whether or not there be excited in the reader a profound sense of dread, and of contact with unknown spheres and powers; a subtle attitude of awed listening, as if for the beating of black wings or the scratching of outside shapes and entities on the known universe’s utmost rim.”

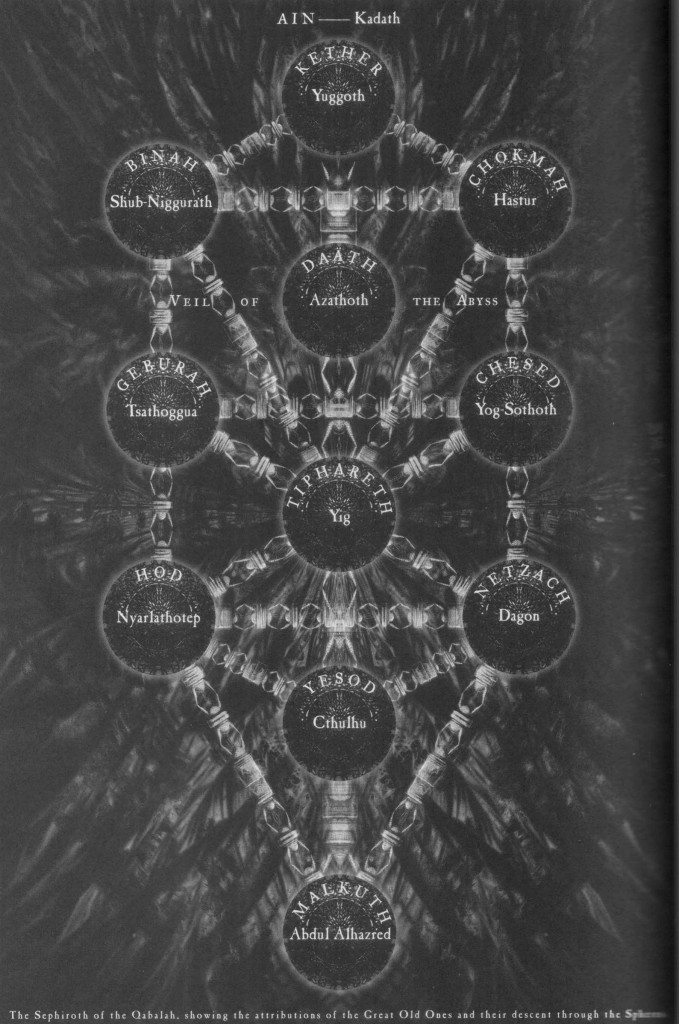

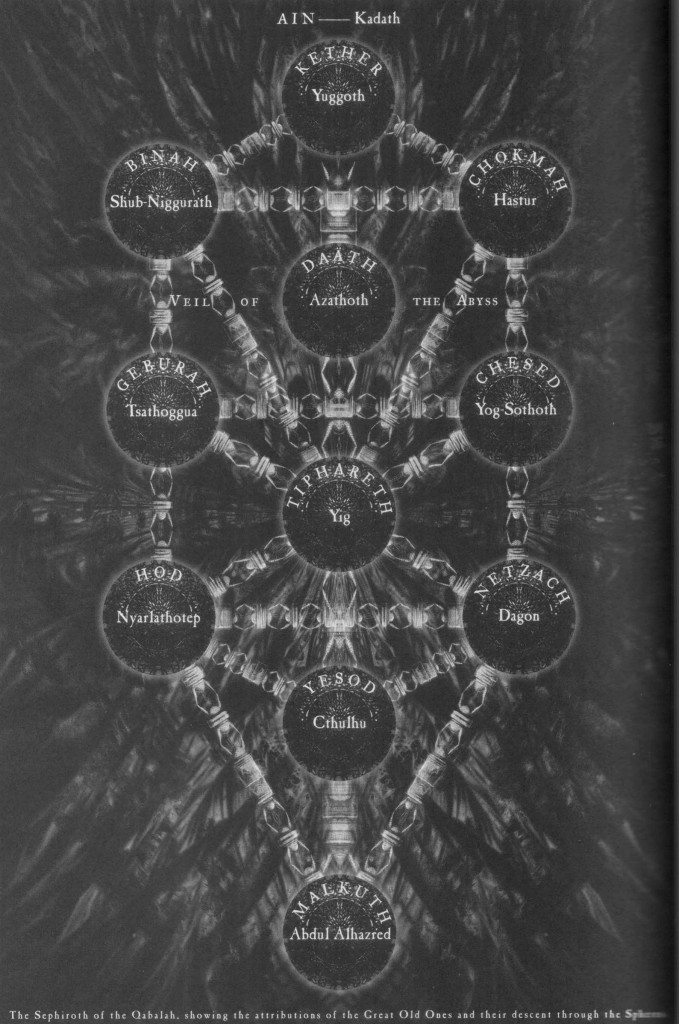

Moore on the other hand is eager to translate this knowledge of depravity to us, to initiate his readers into the mysteries of authorship and creation. Together with John Coulthart [2], he imagines the Old Ones in a Kabbalistic structure where Dagon is Netzach (astringent kindness, the union of the human and divine) and Cthulhu is Yesod. The Aklo is a drug, the “Ur Syntax”, the transforming proto-human language of theophoric words, allowing us to look within to the sexual revulsion and the racial hatred; the fear of contagion and Syphilitic dementia; the horror of “cosmic sin”. His comics a mirror for the evil within our souls.

Notes

[1] Michel Houellebecq’s essay titled H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life is quoted by both China Miéville and Tim Hodler at Comics Comics. Houellebecq denies any latent sexual symbolism in Lovecraft’s stories quoting a letter in which he writes, “I do no think that any realism is beautiful.” Here are some excerpts from the essay:

“Paradoxically, Lovecraft’s character is fascinating in part because his values were so entirely opposite to ours. He was fundamentally racist, openly reactionary, he glorified puritanical inhibitions, and evident found all ‘direct erotic manifestations’ repulsive.”

“Absolute hatred of the world in general, aggravated by an aversion to the modern world in particular. This summarizes Lovecraft’s attitude fairly accurately….if he refused all sexual allusions in his work, it was first and foremost because he felt such allusions had no place in his aesthetic universe.”

“…it was in New York that his racist opinions turned into a full-fledged racist neurosis. Being poor, he was forced to live in the same neighborhoods as the ‘obscene, repulsive, nightmarish’ immigrants…But what race could possibly have provoked this outburst [a racist diatribe describing Lower East Side immigrants]. He himself no longer knew…The ethnic realities at play had long been wiped out; what is certain is that he hated them all…His descriptions of the nightmare entities that populate the Cthulhu cycle spring directly from this hallucinatory vision. It is racial hatred that provokes in Lovecraft the trancelike poetic state in which he outdoes himself by the mad rhythmic pulse of cursed sentences; this is the source of the hideous and cataclysmic light that illuminates his final works.”

[2] Presumably a natural extension of the wild utterances of Robert Suydam in The Horror at Red Hook:

“Malone did not know him by sight till duty called him to the case, but had heard of him indirectly as a really profound authority on mediaeval superstition, and had once idly meant to look up an out-of-print pamphlet of his on the Kabbalah and the Faustus legend, which a friend had quoted from memory…When he spoke it was to babble of unlimited powers almost within his grasp, and to repeat with knowing leers such mystical words or names as ‘Sephiroth’, ‘Ashmodai’, and ‘Samaël’.”

Further reading

(i) The French edition of Les mythes de Cthulhu (drawn by Alberto Breccia) – The gold standard for comic adaptations of Lovecraft. One of the greatest artists to grace the comics form. I suspect Breccia’s adaptation of The Dunwich Horror was chosen for translation by Heavy Metal magazine because it is also the most “conventionally” drawn. The rest of the stories in this collection are more experimental in technique. Breccia’s depiction of Cthulhu and the Deep Ones is also typically unusual.

(ii) The Lovecraft Anthology Volume 1 (SelfMadeHero) – This is the PG-rated version of Lovecraft by a host of British artists. Low on evil, mystery, racism, and violence, this is for the Scooby-Doo set. Give this one to your kids.

(iii) Haunter of the Dark – John Coulthart is the way to go if you’re an adult.

(iv) Yuggoth Cultures – a smattering of Lovecraft ephemera from Alan Moore. Antony Johnston’s Yuggoth Creatures demonstrates what a mediocre pastiche of The Shadow over Innsmouth (and others) would look like.