In comics circles, Roy Lichtenstein is often condemned as a no-talent snob who condescended to comics artists even as he made millions by ripping them off. R. C. Baker in a takedown from last year, for example,not only nails Lichetenstein for his knee-jerk dismissal of his sources, but even sneers at him for his compositions, claiming that Lichtenstein’s “flabby lines, blunt colors, and graceless designs are invariably less dynamic than the workaday realism of the comic pros.” Lichtenstein took the vital, outsider pulp energy of comics and flattened it out into flaccid high-brow capitalist dreck. Rather than elevating commercial product into art, he turned art into commercial product.

This criticism, obviously, doesn’t erase the high-art/low-art binary so much as it flips it. High-good/low-bad becomes high-bad/low-good. Lichtenstein may be a transformative genius or a parasitic hack, but either way he’s defined through his relationship to something else; the thing that is not high art which he is blessing or debasing.

Seeing the current Lichtenstein retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago calls that narrative into question in some interesting ways. Mainly, the show makes it clear that Lichtenstein didn’t copy pulp because it was pulp. He copied pulp because he copied everything. From his early AbEx experiments which look more like half-hearted imitations of AbEX than like the real thing; to his lifetime of imitating other high art painters from Picasso to Matisse; to a series of bizarre Chinese landscape images which include, for no apparent reason, Lichtenstein’s famous imitation Ben-Day dots; to a series of drawings of his own studio in which Lichtenstein imitates his own most famous imitations — the man was a compulsive aesthetic magpie.

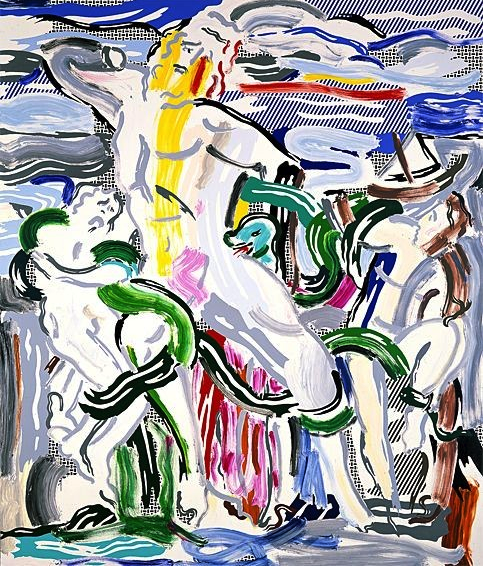

Moreover, the way he treated his non-pulp sources was in many ways similar to the ways in which he treated his pulp sources. For instance, here’s his version of the Laocoon:

I’m not sure that this really comes across in the reproduction, but in the massive original, there’s a stark contrast between the flat moire patterns Lichtenstein uses in the background and the AbExy swoops of paint that define the figures. Lichtenstein also, of course, obscures the characters’ expressions and blurs the narrative action. Some of the energy and pathos of the original are retained, but only in a deadened form. The emotion is presented as thin; a few slashes of paint against a surface that asserts itself precisely as patterned, meaningless surface.

Of course, this is what happens in Lichtenstein’s comics, too. The romance and war panels are lifted out of their narratives. The larger than life emotions end up as merely transparent, flat signs of “larger than life emotions”.

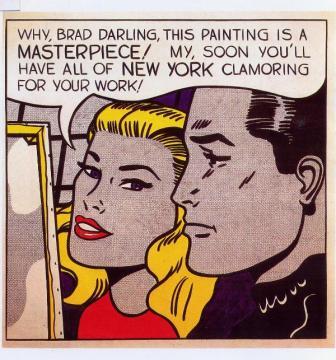

Like Laocoon, the drowning victim here is abstracted from her predicament and inflated; the energy, concentrated and expanded, collapses under its own weight. The panel is just its surface, there is no Brad outside it, and the only thing to do (for good and ill) is to sink.

I think the usual way to read this is as a playful satire of authenticity; a repetition which parodies the original and mocks its melodrama. Often this is seen as a mockery of comics or pulp in particular, but pieces like Lichtenstein’s Laocoon suggest that his target is not so limited. Rather, he seems to be sneering at sincerity and vitality itself — not at melodrama per se, but at emotion. Whether low art romance comics or high art tragedy, both point to depths, and are therefore ridiculous.

I’m sure there’s some truth to that reading…but it’s not necessarily how I see what Lichtenstein’s doing. Rather, at least for me, his work is suffused not so much with contempt as with a kind of etiolated longing. Surely there’s something almost quixotic in those Ben-Day dots; the painstaking hand-crafted effort to replicate the incidental byproduct of mass production. It’s as if Lichtenstein is trying not to ridicule the melodrama, but rather to reclaim it. the replication in this reading is not playful mockery but compulsive failure. He’s trying to frame that originary energy, and is condemned to keep trying and trying until he succeeds, which he never can.

My wife, who is a Lichtenstein skeptic, commented that he’d just had one idea, and it wasn’t all that great an idea, and he’d just kept at it with a numbing regularity. There’s definitely truth to that, and you certainly can see his inability to bottle the energy he alternately/simultaneously mocks and covets as related to his own aesthetic limitations.

You can also see it, though, as part and parcel of the historical moment Lichtenstein was in…and which we’re still in, to a large extent. Late capitalism is not an ideology that cares much about origin myths. Social authority doesn’t come from the divine right of kings, but from the repetitive images of value and community that circulate endlessly without any necessary prototype. Even the Founding Fathers are little more than a subcultural marketing trope at this stage; George Washington is just a cutesy infantilized placemat distributed for fun and profit. Which, not coincindentally, is what Lichtenstein’s version of George Washington crossing the Delaware looks like.

Lichtenstein is obviously a beneficiary and an exploiter of post-modernism…but he also can be seen, perhaps, as a victim of it. Imitation isn’t necessarily flattery, but it almost always has something to do with desire. When he has one of his cartoon women declare , “Why Brad, darling, this painting is a masterpiece!” it may be a sneer at pulp’s idea of high art, but it also seems like a nostalgia for that instantly recognizable work of genius, which that character, and that comic, may believe in, and so perhaps achieve — but which Lichtenstein himself can only wish for.

It’s tempting to see Brad’s sad frowny face as self-portrait; a depiction of that distance and that distress. But of course Lichtenstein is never in his paintings. At best, he’s on the surface.

___________

Folks may also want to check out Kailyn Kent’s recent discussion of Lichtenstein. Scroll down for numerous comments.

He painted the most hilarious meta-painting ever:

http://www.boisseree.com/images/artists/Lichtenstein/Lichtenstein_Brushstroke_gelb_PC_18661.jpg

Does the retrospective have his sculptures in it? There aren’t that many of them, but I find that they are (a) fascinating and (b) complicate some of the received narratives about his work. As does this essay. Thanks for writing it. My grandmother was a huge fan of and friend of RL’s, and I grew up around his work, so I have no critical distance on it.

There were a couple of sculptures, yeah…which I quite like too. How do you feel they complicate the narrative? Because they’re more distant than the inspirations? (There’s a very funny sound effect sculpture which I think is pretty great.)

There’s a detail that you’re not considering, Noah: Lichtenstein didn’t reproduce works of art, he reproduced reproductions. The surface and flatness you talk about is the surface and flatness of the global village, to use an expression of his time.

Yeah; I thought about that while writing but didn’t quite manage to say it.

I sort of get at it when I’m talking about the dots, right? He’s carefully, by hand, creating a reproduction to imitate a reproductive process.

I think part of his nostalgia is about the comics being able to ignore their own reproductive, mass marketness in their unironized melodrama, and part of his fascination is with the reproductiveness itself.

Like Warhol he saw himself as kind of a repro machine.

I’ve never experienced his sound sculptures. I’ll have to check it out should this show come to somewhere I am. I love Bruce Nauman’s sound sculptures more than any of his other works.

Anyway, I think they complicate it in two directions. One absolutely has to do with this surface thing you touch on here. His aquarium sculpture and coffee cup sculpture, for example, are interesting because they’re totally frontal. Even though they’re three dimensional sculptures, everything is on the same plane, giving particularly the aquarium one this almost cubist feel where the fish’s bodies cross the boundaries of the tank that’s supposed to contain them. But then there are also his forced-perspective building facade sculptures, which are three dimensional and deceptively hint at being even-more-three-d than they actually are. In other words, they reinforce your argument here about surfaceness being a feature rather than a bug.

The other way I think they complicate it is what you just mentioned about the source “texts” being much more hidden. he wasn’t doing sculptures of Archie and Jughead or whatever.

Usually people talk about Lichtenstein’s 60s work, but his later paintings (and sculptures, of course) from the mirrors until the 80s, in which he’s almost Neoexpressionist (cf. the Laocoon above), are proof enough that he was a lot more than a one note painter.

It’s approprate that Roy Lichtenstein made images that, whether comics-based or not, seemed illustrational (not only of illustration)– pedagogical, sort of. It’s sort of like all art before the war was saying “primal unconscious!” but really just being secretly about industrial image reproduction– and that was flipped after the war, with art allegedly about mechanical reproduction that actually ends up being about our sub-surface internal simulations.

Heh. Lichtenstein as ExAb.

Pedagogy-wise.. I just mean that Lichtenstein, more than Warhol, Nauman, or any number of more polymath-esque artists, made things simple. “This is how art works, as well as how you see and process viaual information cognitively.” Like a conceptual versioin of pointilism– which is appropriate, dot-wise.

The Lichenstein retrospective at the Chicago Art Institute is great. You find out that he had a lot of phases, so the famous comics paintings comes after a phase of just painting single objects in black on white canvas, and is followed by a landscape phase where different colored dots mark the difference between the sea and the sky. The landscapes and objects are sad and lonely, and distanced, like his mechanical reproductions of comics, but without the melodrama.

And then after the landscapes he did some of those other parodies you mention, but what you don’t mention is that they are hilarious – and that he’s making fun of his own style as much as anything else. There was one I particularly like because after, like, one painting where he introduces curvy green lines, one where he tries stripes instead of dots, one where he varies the size of the dots, etc, it’s just this painting with EVERYTHING he’s ever done, all in one painting, and it’s huge… it just seems really exuberant and over the top by comparison, even though it’s still obviously carefully and meticulously created. The funniest thing though is that it comes with its own border: as if the painting comes pre-made for hanging up in a gallery.

And he also has paintings of his own paintings hanging up, which is funny for the same reason: so much hubris! But at the same time humble, because of the craftsmenship involved.

I dunno, you just have to see these in person (particularly the size and how much the colors pop out) to appreciate how funny they are. And he’s making fun of himself as much as anyone else. Even the comics paintings you’ve seen a million times in reproduction are much more impressive in person. My mom and I went into this exhibits as Lichenstein skeptics and came out converted.

And I felt the same way about it when I found out that Jackson Pollack had a “black” phase when he just

Oops, should have proofread. Anyway, Jackson Pollack also had a “black” phase, where he painted stuff that looks kind of like Picasso’s Guernica. It kind of makes you appreciate his controlled chaotic paintings more.

I do often find Lichtenstein funny. As I sort of say in the piece, this time out I found it more melancholy. You can see it as making fun of his own style…but it also can feel like sort of mourning his own style, or feeling trapped in it. Or that’s what I got out of it in this case, anyway….(though I laughed a few times as well!)

Are you in Chicago subdee? I didn’t know that.

I do often find Lichtenstein funny. As I sort of say in the piece, this time out I found it more melancholy. You can see it as making fun of his own style…but it also can feel like sort of mourning his own style, or feeling trapped in it. Or that’s what I got out of it in this case, anyway….(though I laughed a few times as well!)

I can see that interpretation. It’s sad and funny at the same time, right? Controlled and distanced, but also pointing toward an excess of emotion (huge canvases, bright colors, melodramatic or grandiose topics). Towards the end of the exhibit I could see that in particular – like didn’t he paint a couple of sad (frowning) fish in a fishbowl before he disappeared for 10 years? Only to come back with more (cheesecake this time) comics stuff and then more (Asian this time) landscapes? But for a long time the style seems to have been more of a boon, because he can basically paint whatever he likes – parody or pay homage to whatever he admires – and it’s always instantly recognizable as his work. You build up a body of work that way.

I guess you could say it’s like an optical illusion, sad or funny depending on what the viewer brings to the exhibit XD.

I was in Chicago for a couple days last week visiting family. Normally I’m in New York, though this year I’m in old York in the UK, getting my Masters degree.

Yes; I think both sad and funny…but not just contemptuous of the source material either way, I don’t think.

Good luck in the UK! What are you studying, if you don’t mind me asking?

Pingback: Comics A.M. | Eight months in, New 52 isn’t sales ‘game-changer’ | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

Even when I was a kid, during Lichtenstein’s pop art heyday, I was pleased to see the paintings. Whatever Roy’s view toward his source material, that didn’t change that comics WERE his source material, suggesting there was something more to be found in them than most people at that time were willing to admit. (I think what most comics fans find most distasteful about his comics paintings is that he didn’t paint more superheroes instead of stealing from “lower” forms, like romance & war comics.)

But most people are only exposed to Roy’s prints, or scans of prints, &, as someone above said, you simply cannot really appreciate most paintings that way. There are things you see in the originals – technique, style, the way light plays off them, that sort of thing – that can’t be appreciated through reproductions.

@Noah – Social Research MA! It’s in the Sociology department. I’m doing a project on a particular large-scale job satisfaction survey: how it was constructed and what it actually means. It’s kind of a creative statistics project, I guess, if there is such a thing.

Hey Steven; nice to hear from you again. I agree that the experience of seeing it in person is very different (though that anti-Lichtenstein piece I linked to up top cheekily suggests that they look better in reproduction stuck to the fridge.)

Subdee, I think all statistics are creative statistics, right?

Noah, just pointed me to this article and I enjoyed it, and generally agree with him. A similar exhibit is opening in Washington, DC (then London and Paris). For my take on it see http://comicsdc.blogspot.com/2012/10/rethinking-rascally-roy-lichtenstein.html

Thanks for the info, Mike. I didn’t know that show was travelling!

You are being far too easy on this over-hyped and underpowered painter. He came up with one good idea; incorporate a sheet of perforated zinc as a stencil into fine art. The ultimate one trick pony. Any comparisons with his source images will show how inferior a draughtsman he is compared to Novik, Sekowsky and the other comic book artists he failed to acknowledge. The idea that his line changes because his scale is so much greater than the original comic panels is nonsense; any artist will tell you that even if blown it up to wall dimensions, good drawing stays good drawing.I used to produce film and TV studio backdrops for a living; had I produced his kind of linework from my postcard-sized references, I would never have worked again! Just because his work hangs in galleries doesn’t make it good; it simply means that to many vested interests and critical reputations would be damaged if his work was seriously deconstructed. Why? Because at base there is nothing there.. emperors and clothes, methinks.

This show established pretty clearly that he had numerous tricks. I dislike lots of gallery art, but I do think Lichtenstein is pretty great.

Hey, Noah. I see this conversation suddenly erupted again.

As an illustration (haha) of my point above, I used to think fairly unkindly of Picasso. Not that his work sucked, just that from what I’d seen of it – all in books & prints – I thought it was very overrated & not especially interesting, & called foul on people trying to tell me he was.

Right about the time I moved here, an art gallery ran a show of breakthrough modernist painters, including a couple dozen Picasso paintings (& a few Gaughins, etc.)… & my god, are those things fantastic. The real things were so great I wanted to run my hands all over them. Incredible to look at.

Regardless of what one thinks of Lichtenstein’s comics panels, another exhibit here not long ago (say what you want about Las Vegas, really good art shows pass through here with fair regularity) covered pop/op art from the ’50s-’70s, & among those were Lichtenstein paintings & pop art installations that were really good & had nothing at all to with contextually or stylistically with the comics panels. There were also a couple of those (off the top of my head, I forget which ones) & while I wouldn’t say they’re my favorite paintings of all time, they weren’t bad. At any rate, Lichtenstein was far from a one-trick pony. Some small comfort those who hate his comics paintings can take is that (I gather) he grew rather frustrated with being popularly associated only with those. I know that’s probably scant balance for all the money he made compared to Ross Andru, but any port in a storm, right?

I would really like to see an exhibition of Lichtenstein’s originals alongside same sized PBU’s of the sources -printed on equivalent canvas. I think this would nail his talent once and for all. Good graphic art doesn’t deteriorate with magnification. This has always been used as a defence of R.L.’s work. Not true.

Of course, this show would never happen because the comparison would destroy so many critical reputations buttressed by these works. The RL foundation is simply behaving as any business corporation -preserving its brand reputation and thereby keeping the profit margin high -just look at the merchandising which could be put at risk.

His work displayed no painterly qualities; his grasp of line left much to be desired. His range of colour was actually so much more limited than those evident in his sources. So where are his other tricks? [and don’t give me ‘irony’; that old trope is an excuse for all art which fails to reach the mark]

Finally; notice how RL moved to other source material when Neal Adams and Bernie Wrightson broke onto the comic book scene. He would not have been up to transcribing the work of those talents -they would have killed him stone dead.

“Finally; notice how RL moved to other source material when Neal Adams and Bernie Wrightson broke onto the comic book scene.”

I have to say, that strikes me as pretty thoroughly ridiculous. There were plenty of great comics artists before Neal Adams.

Part of the confusion here is the idea that Lichtenstein’s virtuosity is the reason people were interested in his work. Lichtenstein was part of a long tradition of deskilling in the visual arts. The fetishization of line and skill — comics thinks that makes it more highbrow, but it does the opposite. Lichtenstein is quite aware of that; as I say in the piece, he’s in some ways nostalgic for skill, and his pieces (which obviously reject the virtuoso reliance on originality) are about that, in part.

I’d urge folks to read Bart Beaty’s Comics vs. Art, which discusses many of these issues.

The Lichtenstein show at Chicago was one of the real surprises of that year — the main surprise being the aesthetic effect that so many of these canvases had on me. The flattening of surface and depth; the solidity of the blacks and the subsequent emergence of unexpected shapes (negative, positive); the “all over” effect of the mechanical patterns on canvas and the strange swimming and vibrating sensations that were produced when the works filled your visual field. I didn’t see it coming — familiar as I was with so many of these paintings — but there it was nonetheless.

The second surprise was how prolific Lichtenstein was in the years 1960-70. I was under the impressions that he worked on one series or subject till it was done to death, then moved on. Not the case. Comics, advertising, brushstrokes, high-art appropriations, sculpture, seascapes, mirrors: in that decade Lichtenstein produce some of his strongest work in all these series. One may not like them, but saying that he “moved on” to other subjects when the comic art got too good just doesn’t fit the facts.

The third surprise — a sad surprise — was the complete lack of reference to or examples of Lichtenstein’s source material. This may very well conform with the demands of the RL Foundation or to separate curatorial decisions — but in either case, it is short-sighted. I think that Lichtenstein’s best works do stand up — in effect and practice — alongside their sources. Indeed, the sources help one to “see” what he is up to and what his “tricks” are accomplishing at the level of the canvas.

Beyond that, regardless of preferences, I can only say that viewers who can’t see the differences between Giordano’s work and <a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brushstrokes“>Brushstrokes, or Abruzzo’s panel and Hopeless, or even the more “faithful” re-working/copying of Romita’s lovers and We Rose Up Slowly” perhaps isn’t looking hard enough.

I’d admit, Lichtenstein’s art has its limits for me — pretty extreme limits, in fact. Most of the work after 1975 leaves me cold, and the final rooms of the exhibition (versions of Chinese landscapes and scrolls) were just awful. And his patchwork “greatest hits” murals are a joke. But that doesn’t undo the force of his earlier work, at least for me.

Yes, maybe it’s all a trick — but what art isn’t? And maybe he only has one. But that’s one more than most.

Did I say that there were no great comic artists before Adams? No; thought not. Fetishisation of the deskilling process… you seem rather confused on this point. Yes, there is a move in Contemporary art to pare down their skills base, but in the work of all the major exponents of this movement -Kiefer, Polke, Richter -all transcend their source material, rather than descend from it. Take it from one who has copied Lichtenstein’s [on a larger scale than his originals] for theatre productions: these are piss-easy things to do.

Even his die-hard supporters recognise the dip in his work in the mid-sixties, when he started to flounder around looking for some new motif on which to tie his flimsy device.

Where are the ‘great comic derived pictures after the 60’s?Peter, you say

“The sources help one to “see” what he is up to and what his “tricks” are accomplishing at the level of the canvas.” How so? A really great artist doesn’t need his source material to reveal what he is up to; the art does that.

Yes, art is visual trickery, but most artists can call upon more than one visual device. More than this, a great artist offers us a vision which in some small way changes how we see a part of the world in a different way -forever. Lichtenstein could only offer us a faulty pair of x-ray specs which could be bought in the small ads columns of the comics he plagiarised.

Beyond that, regardless of preferences, I can only say that viewers who can’t see the differences between Giordano’s work and Brushstrokes, or Abruzzo’s panel and Hopeless, or even the more “faithful” re-working/copying of Romita’s lovers and We Rose Up Slowly” perhaps isn’t looking hard enough. – See more at: https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2012/06/the-origin-of-roy-lichtenstein/#comment-159891

Yes, look hard enough, and if you unburden yourself of the weight of cultural propoganda surrounding these images,I think you will be able to tell the difference. Obvious to another painter, anyway.

“all transcend their source material, rather than descend from it.”

So…Duchamp somehow transcended the urinal by turning it upside down?

Pop art is about calling into question these ideas about transcendence, skill, highbrow, and lowbrow. It’s certainly about questioning the privileged position of the “painter” to make aesthetic judgements. That’s why it was, and remains, so controversial, not just with lowbrow craft-oriented narratives, but with highbrow folks as well. Jeff Koons still really freaks people out. More power to him, I say.

Oh, I believe if you read what I wrote a little more carefully, you would see ‘major exponents’; I would also place Duchamp in the academy of the over-rated. But at least he realised that his limited resources would only go so far, and diverted his attentions to chess playing.

I understand the ethos of Pop; but I don’t think it has quite the bite you accord it. Koons is pure establishment product and any sting has been drawn out by the art establishment. An artist like Lichtenstein can certainly travel an arc with a small skills base, but its trajectory,as we are now seeing during this period of critical revisionism, is woefully low, and its range painfully short.

I think you should listen more to your wife [always a good policy, my wife tells me]; she has the finger on this particular pulse.

People really loathe Koons, in my experience. He’s influential, sure, but if his goal is pissing people off, he’s succeeding admirably.

I’d way rather look at and think about Lichtenstein than Neal Adams, who I think is pretty dull. Berni Wrightson is more interesting (especially his Frankenstein.)

““Finally; notice how RL moved to other source material when Neal Adams and Bernie Wrightson broke onto the comic book scene.”

I have to say, that strikes me as pretty thoroughly ridiculous. There were plenty of great comics artists before Neal Adams.”

There were, but the statement also assumes the “panel blowups” were the only thing Lichtenstein wanted to (or did) pursue artistically. As I noted, while the most widely familiar of his work to the general public – by that measure, if you think he mainly wanted to shock the public & the art world into remembering him by redoing comics & calling them fine art, you can’t fault him; that’s what happened – it doesn’t constitute the entirety of his output by any stretch.