A brief satire on Appuntamento fatale (Ballata in si bemolle) (Rendezvous in B-Flat, aka Fatal Rendezvous), a 1997 album by Milo Manara, as most recently translated in Manara Erotica Volume One (Dark Horse, 2012), one segment of a prospective ten-volume endeavor compiling 2,000+ pages of Manara’s comics under various titles.

***

Brother, what I write to you now will reveal more about myself than the book I describe. But still, you have asked for the apex of degradation, and what better venue than this?

Il maestro is summarized most adequately by the woman on the left. Yes, ha ha – it must be a woman! She must be aloof, of course; inscrutable! Unknowable! Nearly an alien race are the females of this species, litters of pups sired from a closely-kept line, all related, no doubt, from the similarities of their faces, their expressions; sisters who blossomed together in that kennel of warm latex flesh. You can’t turn me on with your Japanese PVC dolls, dear friend, for I have women readily sculpted right here on the page. See how she bristles at the thought of “love,” arms thrown up in defense, cringing at the touch of a man!

This, fundamentally, is the feminine disposition under Manara’s pen and brush. He is a great lover of the female form, it is said, but his devotions are such that even the most Roman of Catholics comes to understand some nauseous puritan appetite for denunciation of idolatry. His women can be chipped into particular shapes for the purposes of dramaturgy, yes, but you cannot imagine them as itchy beings any more than you might expect the Pietà to fart.

They are, in a word, perfect, and therefore a most fitting vehicle for the perfection of rape, as you have urged me to detail.

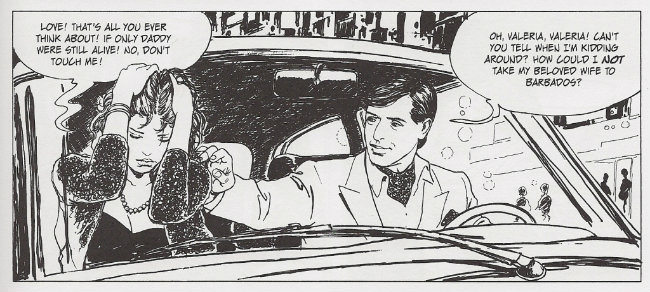

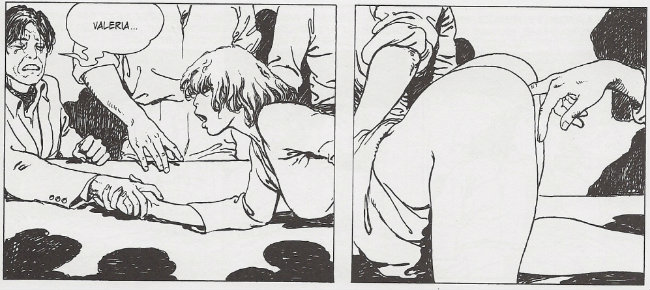

Valeria is a materialist and something of a bitch, which allows the shallow reader to presume she deserves it. We can disregard these lower minds, brother, but a fundament is always necessary to il maestro. Recall how he establishes the book’s relationship dynamics in its opening panel, its subtleties are only discernible in retrospect:

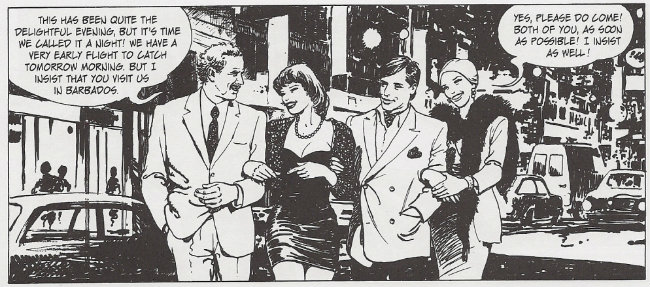

Valeria is not a speaking character. Instead, at the far left, we see the words of the Senator, the reader’s surrogate, to whom the story is ostensibly being narrated, though the fact of narration is not apparent until later; in this way, the confident, virile, powerful man — a happy flattery! — can command the opening of the drama. His arm is locked around Valeria, directly to his right; she touches him gladly, her head bowing toward him, the finger on her rightmost hand pointing toward him, her posture set entirely away from Silvio, her ineffectual husband, whose eyes are either trained on her or the Senator. Such ambiguity is necessary.

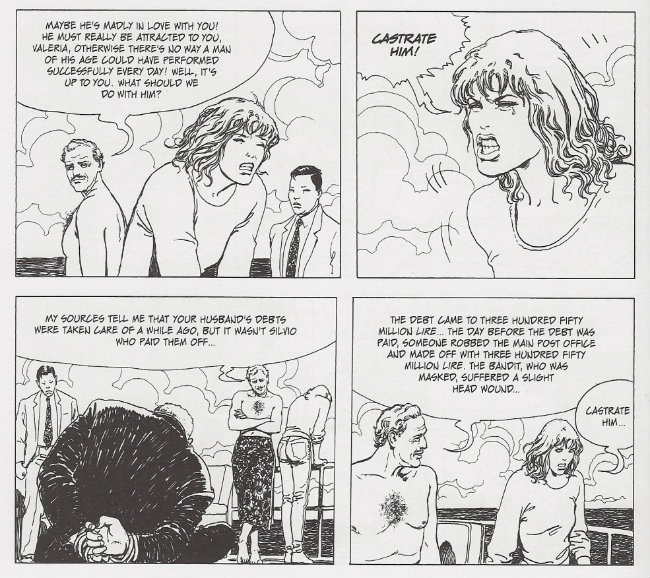

As the plot will eventually reveal, Silvio, the eunuch, whose wife withdraws from his touch, whose torpid marital relations are consigned to off-panel oblivion after an abridged bit of early foreplay — cock-blocked, one might say, by authorial fiat — is the “bagman” for the Senator’s dirty kickbacks, though in some ill-advised gesture toward agency he has begun skimming the take. This cannot do. The Senator is aware of this transgression, and seeks to punish the man through emasculation; he will arrange Valeria’s rape, and, moreover, arrange so that Silvio consents to and encourages such. It is a cocksure bit of comeuppance between men, a sexual fantasy of the lusty Senator, put into being and then, ingeniously, detailed back to him by trusting, narrating Valeria.

See again how only the Senator’s eyes follow the eyesight of the reader: toward the right, brother! See how every other character pushes against the flow, staring left, gazing upon the Man, the reader, yes, and the author! The creator of the story, assessing his cast, all the way back to his nameless date at far right, her face identical to Valeria’s – neither the first, nor the last is she.

All desirable women are the same, in the mind’s eye. They are all perfect.

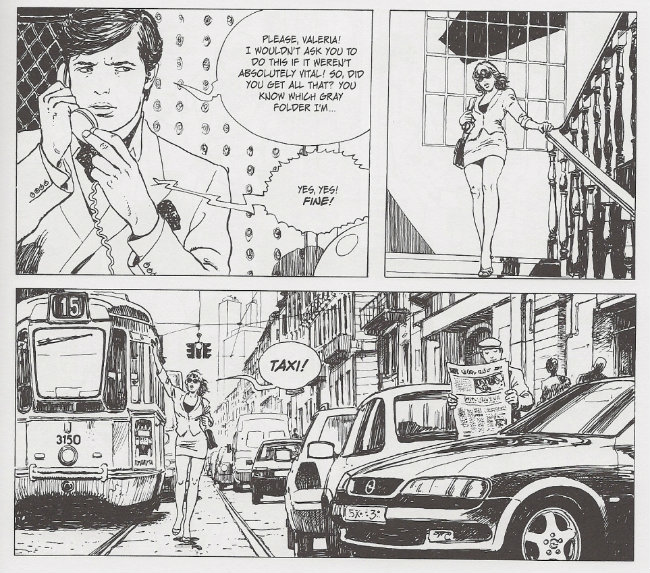

I will not waste time with any detailed synopsis. Suffice to say, the Senator has arranged for Silvio’s financial ruin, which has thrust him into the clutches of a lecherous, corpulent loan shark, who determines that payment of interest will best be taken from Valeria’s body. Silvio is the one who persuades his wife into this peril, thinking, perhaps, that the fat man wants only some quid pro quo. But it’s instant gratification the usurer demands.

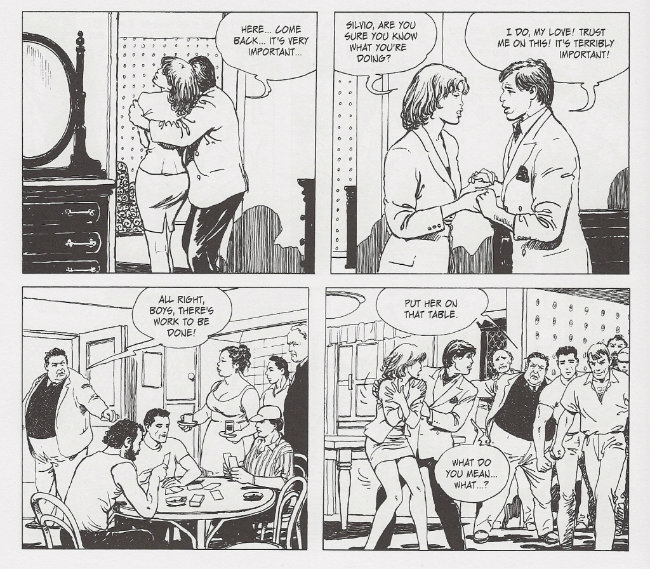

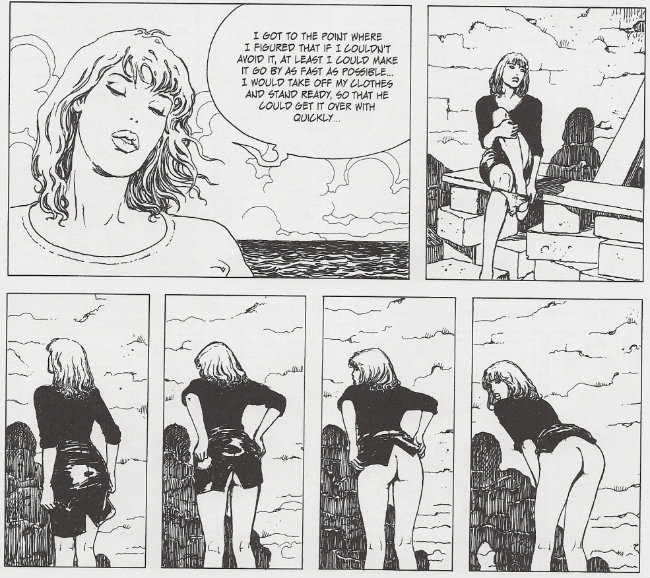

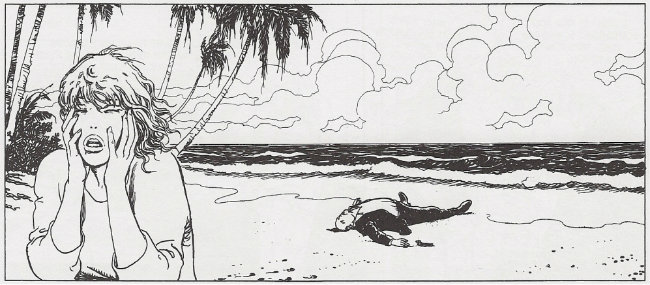

When we see then — here, above — is the genius of Milo Manara. His draftsmanship is beyond reproach, but to only study figuration is to value illustration over sequence, diminishing the function of comics art. Similarly, to only appreciate images of sexual acts is to insult the character of Erotica, which rightly encompasses the psychological textures of the sex act: the anticipation; the anxiety; the flight from one’s senses; afterglow.

By this tradition, il maestro luxuriates in the effect of rape. See how the above diptych appears on first glance to depict one continuous image, though on closer examination it instead shows, in panel one, Valeria gazing in abject horror at the weeping face of the man who betrayed her trust, worthless and weak, unable to meet her gaze, his hand laughable in hers, as panel two closes in, at dead center of the image, on the debutante instance of unwanted penetration, Valeria’s hindquarters enlarged and raised, beckoning to the accorded silent moment of a ritualized insertion.

In panel one she is not raped, and in panel two she has been raped, and will always thereafter have been raped. It is consummate comics.

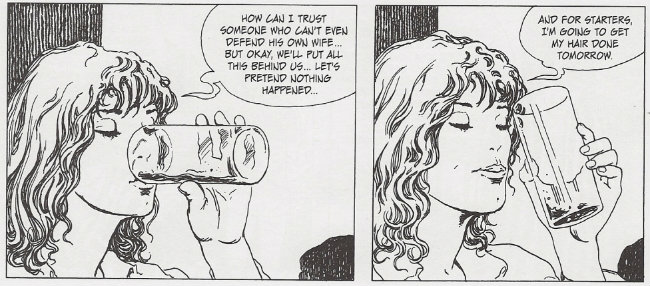

Lest you suspect I am projecting, on the page thereafter the narration starts. Yes, it is only after the first legitimate exploit that the story can truly begin to be told! “I couldn’t fall asleep that night…” Valeria recounts — again, I remind you, to the Senator, who has set these antics in motion — “I felt humiliated… sullied… I’d been defiled… I had suffered a wound that would never heal…”

Here, the journeyman might either stop the tale entirely or embark on some risibly generic revenge scenario. But Manara realizes that Erotica is both peaks and valleys, and best enjoyed through the glaze of verisimilitude. So Valeria seeks to return to her old life.

She is raped again at the salon. Not immediately – for a while, il maestro delicately applies some genuine psychology of the rape victim: “Everything seemed somehow far away… as if I were now in another world! The world of the defeated, the losers…” Such dissociation and self-loathing is typical, and adds fine coloration to the rising action.

After she is raped in the salon, Valeria retreats into her own bedroom, locking Silvio out while he attempts to explain that he can’t go to the police because they too are corrupt. The gang then invades the woman’s last bastion of retreat and rapes her on her own bed, though only after she learns that Silvio had apparently struck a deal with the usurer that his debts would be excused — and his political career preserved — day by day, with his wife being raped every single day: the Appuntamento of the work’s title.

This concept, I confess, borders on silly. It is not unlike Johnny Ryan’s Sherlock McRape, who exchanges his crime-solving prowess for, say, 50 rapes, half up front. The gradual build of the sites of Valeria’s assaults from (1) an unknown location to (2) a beloved merchant to (3) her own home offers some lively and gradual build of excitement, but something more would have to be introduced to keep the comic from becoming monotonous.

Ah, brother! But I have forgotten the story’s hero!

You see, specifically, Valeria is not gang-raped. She is only ever raped by one member of the gang: a silent, hulking man named Ursus, which is Latin for bear. As always, Manara’s symbolgy is deliciously complex – by his ancient designation, Ursus evokes the same Roman milieu as the ‘Senator,’ positioning them both as figures from antiquity, divorced from the weak and the fat of modernity. Yet they are opposites, the Senator all calculation and stratagem, while Ursus is inarticulate and passionate: a real brute!

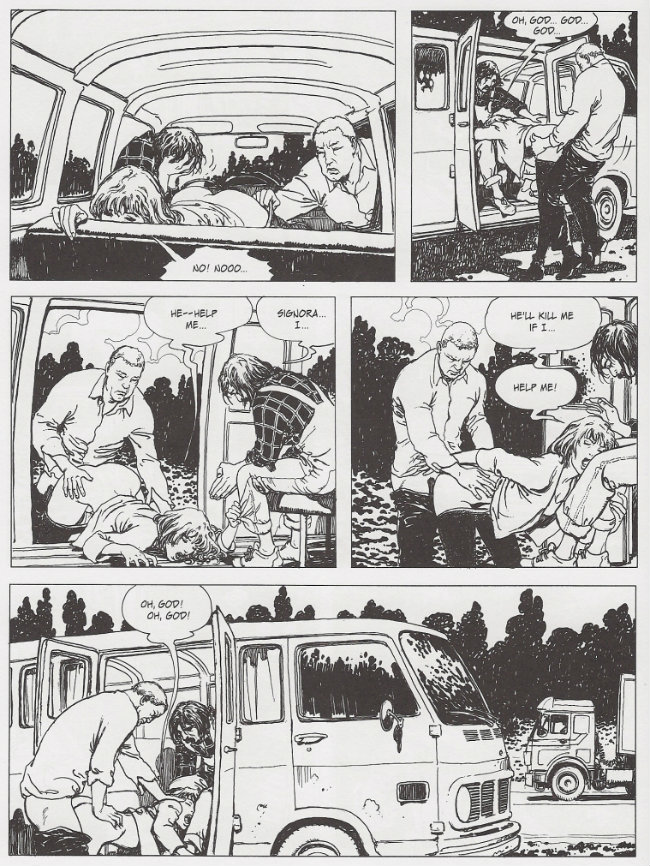

Mercilessly, invisibly — almost supernaturally — he pursues her, even after she packs her bags and hits the road in the dead of night. Yet as the clock strikes six, the appointed hour, Ursus’ car zooms out of the roadside woodwork to block Valeria’s retreat. Withstanding the woman’s blows, he chases her on foot to “a battered old van” manned by proletarian type in overalls. Ursus beats the man furiously, then bends the woman over. She claws at the worker’s leg, but her rescuer does nothing. She maneuvers upward as she is sodomized, her face pressing up toward the impotent man’s crotch, his head lowered in utter shame, in total defeat, he watches the entire process, this woman’s public rape, unwitting vehicles zooming by in the background, her head pressed against his body as she screams and screams.

At this point, you are no doubt detecting a political subtext to the action. In fact, il maestro previously added an element of social critique to the encounter in the salon, as an ignorant woman clucks over how handicapped people would do better to stay at home than expect accommodation from a hotel. Such insensitivity from those unaccustomed to pain! Yet because this is not a bathetic work, a representative of the loan shark’s gang offers his own declaration upon entering the scene: “If you want to enjoy the good life, my dear signora, the piper must be paid!” If you’ll recall once more the work’s first panel, and what immediately followed, you’ll know that bourgeois Valeria herself was very much interested in joining the Senator, the reader, “in Barbados,” nudging her lover further toward the pit of misery into which she now herself is cast.

Turnabout, truly, is fair play. In this way, Manara evokes an earlier Italian parable of class warfare, Lina Wertmüller’s 1974 film Swept Away, though his intensity better matches what I’ve read of an inaccessible pinku eiga by the great Japanese subversive Masao Adachi, 1969’s Sex Play (Seiyûgi), in which leftist students reject the timidity of ‘non-consensual’ role-play with girlfriends to commit actual rape: a metaphoric embrace of direct action politics, and a challenge to the moralistic paradigm necessary to accomplish the revolutionary project.

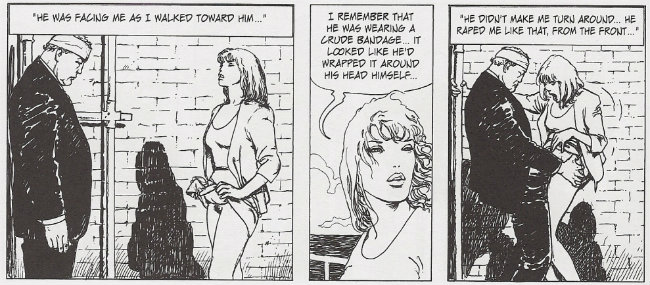

Manara thus begins to intercut Valeria’s continuing dalliances with images from her narration aboard the Senator’s yacht in the Caribbees. “It is simply unacceptable for the rabble to rape our women!” the powerful man muses, arms folded, assuring the woman that Darwinism accords the elite a natural right to command the public. But Ursus too is a worker, and the peerless accomplishment of his set task, day after day, begins to impress the woman:

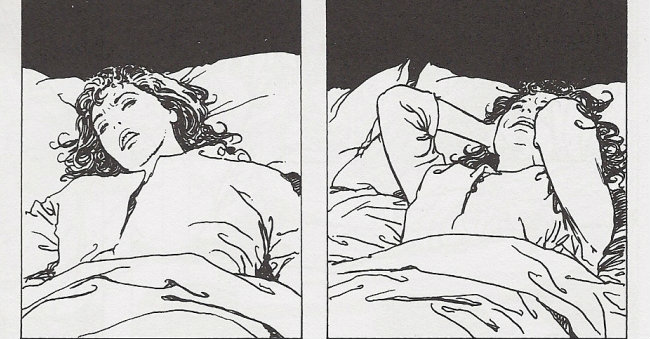

There! There it is, brother! The face! The Manara face, in the final panel! Ooh, the lady doth protest too much! Another one:

This moment marks a major turning point in the story; prior to this, we are told, Ursus had only ever entered Valeria through the anus. As we will eventually learn, the bandage on his head is due to his covert efforts at paying off ridiculous Silvio’s debts through his own industry. The symbolism is powerful – anal sex is immoral and unnatural, per the Catholic outlook of Manara’s work, so vaginal intercourse can thus mark a sea change in Ursus’ affections: bringing the woman food, tending to her shell-shocked state all holed up in a boarding house. He continues to fuck her at six, of course — a working man has his duties — but unlike the limp grotesques previously seen as challenges to the prevailing social order, Ursus is physically inspired. The last romantic hero.

But forgive my sentimentality. These comics are about women.

Il maestro knows. In all of these beautiful images, there is not a hint of the ugly male anatomy: the leering prick; the dangling, imbecilic pouch. I am not the sort of man who is so insecure that he cannot stand the sight of a woman being goodly fucked, brother, but need I be perpetually confronted with the wan issue of coughing rods at the conclusion of every episode on the erotic midlist? Goddamn it, this is better. There is no emanation from Valeria. She does not drool or sweat. Her eyes do not water. We are spared the potential of her scent. She is the quintessence of the Manara woman. She is perfect, perfect, flaxen glow perfect, tawny sunbake perfect, ceramic milk white perfect, every color of perfect, perfect, perfect.

Until! Until!

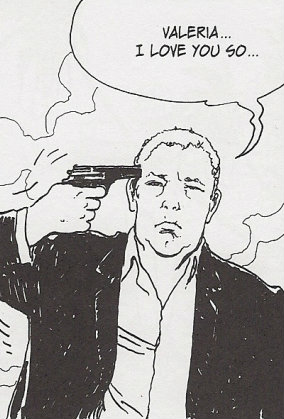

The second panel above depicts the only instance of fluid definitively seen to escape Valeria’s body over the course of the story. It is a single tear. Ursus has somehow made his way to the coast of Barbados, again in pursuit of his departed love. He has blown his deadline, and is in a bad state. Sneering, the Senator/reader/author spells out what’s happened to Valeria, but she will hear none of it. The rapist must be punished. From this, most readers conclude that Appuntamento fatale (Ballata in si bemolle) is a sad story of perverted, frustrated love, ruined by circumstance.

Pity their lack of vision, brother. A masterpiece must have more.

The great manga artist Toshio Maeda once remarked, “[m]es titres s’adressent aux hommes, adolescents et adultes. Ils veulent y voir des filles violées ou des scènes lesbiennes.” What is crucial is that des scènes lesbiennes are in parity with des filles violées. They are fantasies, yes, but also safe spaces for male desire, for the admiration of women.

Yet non-consensual scenarios are not a purely male space, alas. You need only look to kink.com, or yaoi manga, or any number of places to know that the certainty presumed of these ideas are increasingly, viscerally feminized, beyond the old romance novel and soap opera tropes. God, it is confusing. Can’t anything be exclusive? What, pray tell, is the gossamer boundary between a fantasy of male domination and a fantasy of female submission?

It is, I argue, the subtle presence of the feminine perspective. The suggestion of exchange – of secret, implied consent. Of knowing.

And a Milo Manara woman can never know you. And you can never know her. It is the metaphysics of his line. The locked sameness of his luscious designs. The alien poise of his beauty, god. Always, there is potential with him, and here, with Ursus standing on the beach, castrated, summarizing the plot to a disbelieving Valeria, we finally, totally know praxis, so that the rape of a woman can inevitably be no less than the furied trauma of an ultimate man.

Beauty without tears.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.

Porco Dio! I’d always found Manara repulsive…but this!…

Jog,

I’ve always enjoyed your writing on comics, but this is my favorite. It hit me like a punch in the gut, and I’m still collecting my thoughts.

Yeesh. This sounds like everything I’ve ever found off-putting about Manara amped up by a thousand.

Very nice. I especially like the introduction and first section.

But as you say the whole rape fantasy angle is getting more and more common in comics and popular culture. Verhoeven’s Flesh and Blood and Kim Ki Duk’s Bad Guy (woman falls in love with rapist in both) come to mind immediately and I’m sure there are much much more. Bad Guy in particular seems to be trying to say something “important” (I have my doubts). The Verhoeven seems to have more to do with the director’s desire to portray a kind of pulpy medievalism. Manara’s version seems, in some ways, less offensive because of his drawing style which is the equivalent of a high end porn video with plasticized women. It’s stupid but you also can’t take it seriously. And it seems, from the images, like the rape victim still hates him a bit in the end (a small mercy?). Torture, rape, and humiliation porn made by women is way more disturbing.

That’s the thing, though – Manara’s also done the “pulpy medievalism” thing, most prominently in Borgia, which Alejandro Jodorowsky wrote in basically the manner of a ’70s Euro exploitation movie, whippings in the convent and all. And I liked the 3/4s of that I’ve read! What’s particularly risible to me about Fatal Rendezvous is that it’s SO specific with its use of rape, and so comprehensive in its stacking the reader’s sympathies toward the rapist – that Valeria still hates Ursus at the end only plays into that, because *of course* she hates him, and *of course* he loves her, having been essentially (tragically!) murdered by her after trying to ‘save’ her! For me, the sterile porniness of Manara’s art aggravates this sensation of the woman’s humanity being vanquished… but that’s a pretty common feeling I get from Manara. Neil Gaiman, at least, had the clever idea to make the [D]esirable Manara woman a literal demigod in the Sandman story they collaborated on…

You could well be right. Unfortunately, I haven’t read any of those Manara comics, nor do I intend to. The last thing was probably Trip to Tulum. I gave up on him decades ago.

The images above do tend to suggest that Fatal Rendezvous is slightly removed from his porn stuff. If it’s not rape fantasy-porn, are we supposed to take it as seriously as Indian Summer? There was (?attempted) rape in that one as well but we can probably blame that on Hugo Pratt at least in part. He could have been writing to Manara’s strengths as an artist. Does Ursus look a bit like Pratt?

Also, the thing about Manara women being basically all the “same” (as you state) is certainly true. Does this mean that everyone else in the Gaiman comic was “ugly”? All the women in Manara’s X-Men comic seemed to be the same on a casual glance.

Well, the album’s a bit baffling in that way. I have no idea how it was framed or sold in Europe, although I think the older Heavy Metal translation pitched it as an adult ‘thriller’ of some sort. Amusingly, the Manara Erotica anthology edition declines to so much as mention the work in any of its contextualizing supplements… maybe they’re stumped too. While I emphasize the work’s prurient implications in this essay, I kind of suspect Manara’s intent was honed in more on the political aspects I mention – it’s definitely not as frivolous in tone as the Click! albums, say, which basically treat the sexual humiliation of women as one passing amusement among several…

I do need to clarify one thing – I didn’t say all of Manara’s women look the same, just the *desirable* ones. There are a number of ‘less attractive’ female characters in Fatal Rendezvous, particularly the lady who castrates Ursus, but none of them are presented story-wise as romantic or sexual actors. Ursus does look a little like Pratt, though, now that you mention it… but I wonder if Manara’s admiration for Pratt simply prompted his adoption as a default rough-but-honorable character design, rather than any specific reference? There’s a rather similar-looking/characterized guy in the more recent Pandora’s Eyes.

There’s also a human Manara woman in the Gaiman story… haven’t read it in years, don’t have it on hand, but I do recall there was a pronounced difference between the presentation of both. Gaiman actually has Manara introduce some androgyny to the ‘Manara woman’ character design — I attribute this to Gaiman, since that’s a general attribute of the Desire character in the Sandman series — which creates a somewhat interesting effect. I don’t recall it being all that good a story, mind you – just a clever use of Manara’s style.

X-Women, in contrast, embodies the old Alan Moore line about Manara’s women looking like the same actress in different wigs…

‘Torture, rape, and humiliation porn made by women is way more disturbing.’

Why?

Suat: “Does Ursus look a bit like Pratt?”

Yup…

Great post, by the way…

Jog, “the sterile porniness of Manara’s art”…beautiful!

—————————

Jog says:

X-Women, in contrast, embodies the old Alan Moore line about Manara’s women looking like the same actress in different wigs…

—————————-

More from Moore:

—————————

Q: Do you know the work of Italian erotic comics artists at all?

Alan Moore: …Generally, it’s not to my taste….Even with, say, somebody like Milo Manara, who I recognise as an incredibly good draughtsman…when I have seen some of Manara’s solo erotic work…The women seem to be pretty much the same woman with different wigs on, there doesn’t seem to be any individuation of the female characters and they do seem to be largely sex mannequins…

—————————

http://alanmooreworld.blogspot.com/2012/07/alan-moore-about-italian-erotic-comics.html

—————————

Jaelinque says:

‘Torture, rape, and humiliation porn made by women is way more disturbing.’

Why?

—————————–

Not that I necessarily agree, but there are several possibilities:

– Those women creators have “introjected” (absorbed within their psyche) the attitude that finds that stuff arousing;

– They don’t like it but are “prostituting” their creativity to serve some male tastes;

– If they do like it — as with the “bodice-ripper” romances — it indicates an acceptance of the attitude that a “good woman” must be passive, forced into sex, ideally by some hunky, good-looking, rich nobleman who loves her so much he can’t help himself… And a great romance will ensue. (Sheesh, this is a standard convention of a massively-popular genre of books! But because it’s women eating this stuff up, somehow it’s accepted, while we get all this frothing at the mouth over Sally Jupiter “falling in love with her rapist.” Never mind that the would-be rapist is shown as a creep, even if a charismatic one, Sally J. — who despises Blake as much as she “loves” him — depicted as more than a bit of an emotional weakling.)

By the by, for those so righteously condemning Alan Moore for somehow “normalizing rape” or other such crime, contrast these scenes of attempted rape…

In “V for Vendetta,” art by David Lloyd:

http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/v-2c.jpg

In “Watchmen,” art by Dave Gibbons:

http://geek-news.mtv.com//wp-content/uploads/geek/2012/06/watchmen-rape.jpg

http://subcultureforthecultured.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Watchmen-1.jpg

…with Manara’s manure (a cheap shot, but richly merited), where even in extremis, his brainless-looking sex mannequins pose prettily, are so helpless they’ll passively “take it all” (particularly in the van scene) with barely any restraint required, their distress shown by demure oohing and aahhing, and cries of “Oh, God! Oh, God!”, indistinguishable from normal coital calls.

A thoughtful article on the abuse of rape in films:

http://www.hitfix.com/blogs/motion-captured/posts/the-bigger-picture-what-happens-when-we-find-the-line-as-viewers

What he writes applies to comics, too.

Mike,

These are all valid points, although I’d argue that the fact that the women ‘“introjected” (absorbed within their psyche) the attitude that finds that stuff arousing’ (thanks for the new word, btw) is, while sad, quite understandable as a way for a woman to form her sexual identity not despite the culture and society largely opposing her gaining agency, but in tune with this opposition. One can, however, find that disturbing.

Thing is, I’ve mostly witnessed the discussion of ‘torture, rape and humiliation porn’ in regards to the yaoi/slash fanfiction. And there… let’s say, the reading of the phenomena is often quite different.

Actually, of course those “bodice rippers” are heavily critised by the same sort of critic who had problems with Sally Jupiter. It’s just for the most part the people who get offended by criticism of Moore’s portrayal of Sally (and his use of rape in general) are ignorant of this criticism as it doesn’t interest them.

Also, don’t underestimate the readers of such novels; they’re often quite aware of the problems with them, but use them as fantasy fodder.

Manara’s sof core porn in general is problematic of course, often depending on some sort of device to force a woman into sex, after which she of course can’t get enough of it. But this seems to be worse than most.

——————-

Jaelinque says:

Mike,

These are all valid points, although I’d argue that the fact that the women ‘“introjected” (absorbed within their psyche) the attitude that finds that stuff arousing’…is, while sad, quite understandable as a way for a woman to form her sexual identity not despite the culture and society largely opposing her gaining agency, but in tune with this opposition. One can, however, find that disturbing.

———————

Indeed, women taking on these “treating women badly is sexy” attitudes are “going with the flow” of a society bent on keeping them down; encouraging every belief and behavior which does so. Did I remotely hint otherwise, or indicate I approved?

——————–

Martin Wisse says:

Actually, of course those “bodice rippers” are heavily critised by the same sort of critic who had problems with Sally Jupiter.

———————-

Oh? You mean, a jackass who can’t tell the difference between moronic, formulaic fantasy that feeds the most self-destructive attitudes in women, telling them that rape = romantic passion, and a nuanced portrayal of a complex woman and her often self-destructive attitudes? Sadly reflected by many women in real life? Who is criticized, treated as pitiful for finding the creep romantically appealing in some ways? (Even while with fierce protectiveness she tells him to keep away from her daughter.)

While the “bodice rippers” tell women that they are right to not only excuse, but think glowingly of males who force themselves upon them? (If they’re good-looking and rich, anyway.)

———————–

It’s just for the most part the people who get offended by criticism of Moore’s portrayal of Sally (and his use of rape in general) are ignorant of this criticism as it doesn’t interest them.

———————–

Sorry; I can’t be massively fascinated by critiques of every possible bit of crud aimed at the lowest common denominator.

And pray tell, what is so offensive by Moore’s “use of rape in general”? Does he glamorize it, soften its degrading brutality? Does he show his women characters being turned on by it, or deserving it? (Sorry, but the idea that the noxious Helen Heyer had been, or was about to, get “deservedly” gang-raped at the end of “V for Vendetta” is malarkey. Apparently, to paraphrase Dr. Wertham, “there are rapes within pictures for feminists who know where to look.” Why, they have the power to peer off-panel in a “Watchmen” scene and not only tell that Sally Jupiter is getting raped outside the frame, but getting anally raped!)

Defending the literary usage of rape, check out Caitlín R. Kiernan’s comments, quoted in my September 19, 2012, 5:41 pm post at https://hoodedutilitarian.com/2012/09/v-for-vile/ …

———————–

Also, don’t underestimate the readers of such novels; they’re often quite aware of the problems with them, but use them as fantasy fodder.

————————

*Sigh*; what ever happened to “consciousness-raising”? Ah, the “cult of the victim,” that’s what…

And do guys get similarly excused for their “problematic” erotica if they’re often quite aware of the problems with them, but still use them as fantasy fodder?

“Oh, but that’s completely different! Men — white, heterosexual men [sneer] are wallowing in their white, hetero, ableist privilege, while women (even though they’re strong, independent, liberated, every bit men’s equals) can’t remotely be held responsible in any way for what they’ve been forced to do or believe. Women are strong (‘hear me roar!’) and self-reliant, but totally helpless victims too.”

Pingback: 2013 Releases to Keep an Eye on, part II | Filth and Fabulations

Pingback: “To Insult The Character Of Erotica” – ErosBlog: The Sex Blog

Pingback: “To Insult The Character Of Erotica” - Lust My Body