Welcome to the 5th anniversary celebration of the Hooded Utilitarian. It was five years ago today that I put up my first post on this blog. It’s been a pretty amazing run since then, and I am incredibly grateful to all the friends, writers, colleagues, commenters, and readers who have kept the blog going for all this time. Thank you.

_______________

Okay, that’s enough with the love. Through much of this month, we’ll be running a roundtable titled Anniversary of Hate, in which contributors will write about what they believe is the worst comic ever — or the most overrated, or the one they personally hate the most, as the case may be.

Anniversaries are usually supposed to be a time of congratulations and good cheer. So why, you may wonder, have I chosen to poison a happy event with bitterness and contumely? Why be a divider and not a uniter? Why hate?

There are a bunch of reasons that I’ve chosen this celebration for this occasion. The first, and perhaps the most important, is that once it occurred to me, I had to go through with it. After all, what’s the point of having a blog if you censor your cranky, or (for that matter) your ill-advised ideas? Besides, lots of folks think of HU (rightly or wrongly) as a place of spiteful animadversion and mean-spirited contrarianism. It would be wrong to disappoint.

I can, however, also come up with some marginally less flip rationales. Indeed, I think the need for justification is a kind of justification in itself. No one, after all, would ask, “why love?” if I asked people to write about their favorite comics.

Criticism tends to be biased towards positivity. In the first place, people simply prefer to spend their time with comics they like. Certainly, for this project, several potential contributors begged off because they couldn’t face rereading a comic they loathed. Along the same lines, negative criticism can have unfortunate personal and career implications for folks who work in the comics field — again, I had a number of writers decide they couldn’t contribute because they didn’t want to offend friends or colleagues. And even where such practical considerations are not an issue, many writers simply prefer to avoid negativity, either because they find engaging in it personally depressing, or because it seem cruel, especially when the target lacks stature or has long since been buried in the slag heap of history.

I understand all those arguments against hate (and I certainly fault no one for turning down the invitation to participate in this particular orgy of animadversion.) But at the same time, I think it’s worth occasionally pushing back against the logic of praise. There is, after all, a lot of bad art in the world. Rushing to insist that the glass is ¼ full (or 1/12 full) can leave you ignoring the vast bulk of the nothing that’s there. And that, in turn, can give you a skewed view of the state of the good art, as well as of the bad.

Perhaps more importantly, a refusal to criticize is almost always a de facto endorsement of the status quo. Good and bad are relative terms — and that means that they are always relative to something. Canonical comics are canonical because they fulfill certain criteria — because, say, they are about important subjects like the Holocaust, or because they show a certain kind of mastery of a certain kind of technique, or because they are works of individual genius, or what have you. To question those criteria, to envision a new canon, or a critical landscape in which canons are less important, requires not just positive advocacy, but negative questioning. That’s why Domingos Isabelinho’s longstanding effort to bring attention to what he considers undervalued works has also required him to do a fair amount of sneering at what he considers overvalued ones. (Update:Though note Domingos’ caveat in comments below.) As Arlo Guthrie once said, you can’t have a light without a dark to stick it in — and you can’t imagine a better way if you refuse to see the flaws in the way you’ve got. Which is why the antipathy to negativity can itself, I think, be profoundly depressing. When you’re angry or unhappy, there’s nothing quite as dispiriting as people lining up to demand that you be of good cheer.

I also think that it’s worth giving folks a chance to write about what they hate simply because hate is as likely as love to provoke, or inspire, great criticism. Whether it’s James Baldwin’s epic deconstruction of The Exorcist, or Laura Mulvey’s brief, brutal takedown of Hollywood cinema, or Mark Twain’s hilarious backhand to James Fennimore Cooper, or Jane Austen’s vivisection of the gothic novel, many of the greatest, most insightful, most beautiful examples of critical writing we have are negative. That’s a tradition worth honoring.

Finally, I suppose I hoped that an Anniversary of Hate would prevent me from getting too comfortable on my laurels (to the extent that I have any.) Five years is a really long time in blog years — long enough to get old and fat and complacent, anyway. But if I’m going to be old and fat and complacent, by god, the least I can do is to be crotchety as well. As we hobble towards elder-blog status, I do hope that somewhere, somehow, we can still provoke some unsuspecting young surfer to mild irritation — and perhaps even, on rare occasions, to hate.

_______

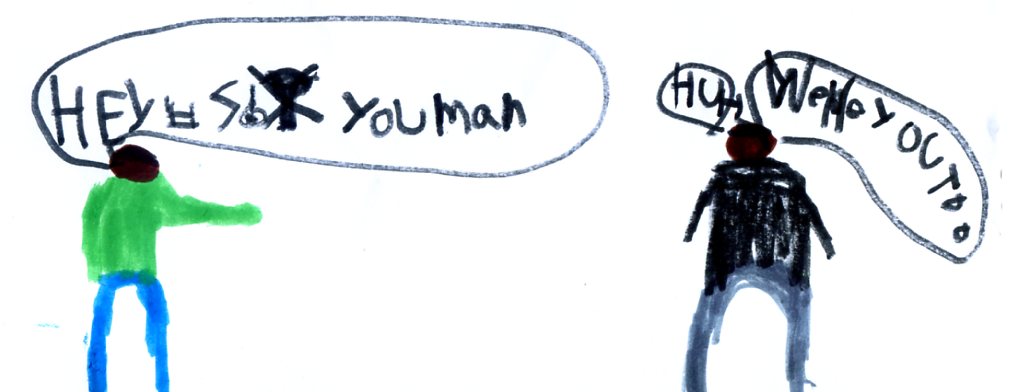

Hatefest illustration by my son. He was 3 when I started the blog; now he’s 8.

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.

Hmm…I’d posit yet another value of negative criticism — that it stirs debate, even when the critique is itself flawed.

As an example, I’d cite T.S.Eliot’s 1920 essay on Hamlet, in which he terms it an “artistic failure”:

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/learning/essay/237866

This interpretation of the play has not gained any lasting adherents, but the text is considered one of the founding documents of literary criticism.

To mix metaphors, it’s also fitting for a devil’s advocate to tease a sacred cow…

That’s true…though I think positive criticism can also generate debate and controversy.

Sure, but consensus cases like Hamlet or Maus (ahem) need a dash of sourness in the critical salad.

Maus will be addressed.

The main reason to not write about the things you hate is because there’s only so much time in the world, so why waste it on things you don’t like! And the main reason *to* write about things you hate is it’s the best way to improve your own art. When things are well-executed, especially when they’re very well-executed, it can be hard to break them apart and figure out how they work. When things are badly executed taking them apart is much easier.

That’s a nice formulation…though inevitably I’m not sure I’m entirely sold. Sometimes the appeal of really good things isn’t especially complicated (much Dr. Seuss, for example) while it isn’t always easy to figure out precisely what’s wrong with bad work.

Personally, I find it hardest to write about things I’m indifferent to. Good or bad I can usually find something to say, but when it’s in the middle it can be hard to get a toehold.

Congrats on reaching the five-year mark! I’m not impressed.

(contrarian enough for you?)

No, that is insufficiently contrarian. Damn it.

Pingback: Comics A.M. | Ursula Vernon’s Digger wins Hugo Award | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

I’m with subdee, at least on the value of negativity. I know I was glad to get a chance to join in, since I tend to write positively about things I like, and I could stand to flex those muscles of negativism a bit more. And yes, I definitely agree that the middle ground is the hardest to write about, since it’s harder to express apathy or say “some of it was okay, but some was boring, and it could’ve been better…” That’s where the much-reviled term “meh” fits in, and it may be why it’s such an annoying reaction, because we’ve all had some book/movie/show/whatever that has provoked that reaction and have had trouble expanding criticisms beyond it.

So anyway: Yes! Let’s see some hate! I love it!

Noah: “That’s why Domingos Isabelinho’s longstanding effort to bring attention to what he considers undervalued works (link) has also required him to do a fair amount of sneering at what he considers overvalued ones.”

And yet… in all my years writing about comics (22) I wrote exactly three negative texts (Nemo Vol. 2, # 21, 22, 24 – the last one about Asterix -, 1996). I write about what I like, mostly… In 17 Monthly Stumbligs I wrote exactly *one* negative post (about Tintin in the Congo). My negative comments were just that: messboard and blog comments. Definitely not negative criticism.

link.

Thanks for the link! Should have put it in the text; my apologies.

It’s interesting that you separate comments and criticism in that way…I think a lot of folks do, and I do myself to some extent…but at the same time I sometimes think that the line isn’t that hard and fast. I sometimes write things I’m quite happy with in comments…and then sometimes not so much in articles.

Which is why I keep turning various people’s comments into post, I suppose; for better or worse.

I’ll put the link in, though, and an update noting your caveat.

You’re welcome and there’s no need to apologize.

I see what you mean and I don’t disagree, exactly… The think is that a comment as I practice it doesn’t really engage with the material. That’s just self-criticism above. (Now that I think about it, it seems to me that I never really criticized a super-hero comic!)

That sort of gets into why it’s often difficult to write negative criticism…in a comment you don’t feel like you actually have to go reread the thing. But for a more formal piece people often feel they do — and obviously no one wants to reread stuff they hate. I mean, I actually got rid of In The Shadow of No Towers because I didn’t even want it in the house.

With the super-hero comics, you have such strong objections to the genre as a whole that it would be weird to see you actually pick a particular comic and go after it. Why bother to point out that this particular issue of X-Men is poorly plotted (or well-plotted) when you find the whole idea of championing the good by blasting at supervillains ideologically heinous?

Again, this is why there’s less negative criticism; people focus their attention not just on particular works they like, but on genres or classes of work that don’t make them want to tear out their sense organs. And criticizing whole genres tends to be especially fruitless, because the only people who care about them are folks who like them…so you just end up frustrating everybody.

Noah, you seem to be providing a stealth intro to my piece…

Yup… not to mention that criticizing a whole genre is a tad ridiculous because it’s such a huge generalization. I sometimes try to read genre comics, but I get bored after a few panels: seen that, read that, know all about it… next!…

Your piece goes up tomorrow, Matt.

Personally, I find it much easier to write -ve than +ve. When I try to write +ve, I usually end up feeling like a tongue-tied doofus asking a girl out on a date — Duh, uh thinks ye’re purty — my critical acumen is not up to the task.

But, in general, I think that analysing failure is at least as important as analysing success. If you only ever think about good art, you may know why it’s good, but you probably won’t know why it isn’t bad.

Jones, that last comment resonates with a terrific book I’ve just read– ‘To Forgive Design’, by the engineer Henry Petroski.

He points out that progress in engineering comes far more often from the study of failure than of success. Case studies include the Columbia Space Shuttle disaster, or the collapse of the Tacoma-Narrows Bridge…

Something analogous might be applied to aesthetics.

“Hate” itself is overrated. Peter Bagge put more work into his artwork than his writing. The unfortunate results were stories and characterizations that leaned heavily to the glib. Jack Baney had a letter published in Hate #14 or thereabouts with basically the same point.

Bagge had some bad experiences with religion in his early life, apparently. Rather than tackling this in a more thoughtful manner (like the South Park guys), Bagge resorted to glib putdowns of religion. I’m referring specifically to certain stories in the “Buddy Does Seattle” collection.

I’m not contributing, but not because I don’t want to offend “friends or colleagues”. My immediate impression when Noah said he wanted to do this was that people would get hurt….even if the maker of the hated work was dead, they have surviving family. Sure, there are comics I dislike, and individuals who do things that I don’t appreciate—but if they come up, I hope it is in the course of analysis, not in the pursuit of negativity for it’s own sake.

I generally feel that if you put yourself out there in public, it’s fair game for negative criticism. Art is in part an argument; Chris Ware or Geoff Jones (for example) are presenting a vision of the world, of art, of beauty, and of how those things interact. I don’t think it’s fair to say that people have to acquiesce to that for fear of hurting someone’s feelings, any more than I’d say that you shouldn’t criticize this project for fear of hurting mine.

In any case, I don’t really see why it’s more wrong to ask people to think about their most hated comic than about their most loved. Both are presumably things that matter to a critic or a reader. The negativity has already been perpetrated in most cases; Bert’s already been made miserable by Chris Ware; Matt’s already been made miserable by contemporary superhero comics. Writing about it is pushing back against the misery, I think.

I guess the point is that there are a lot of things to be unhappy about in the world, as you say. Probably more than there are to be happy about, really. As such, negativity seems like a natural response — and sometimes one that can make things seem a little cheerier.

Steven, I’m pretty embarrased by the letter I wrote to Peter Bagge urging him to stop making fun of Born Again Christians. At the time, I was a freshman in college and thinking about getting “born again” because of the influence of some guys in my dorm (they very intelligently tend to go after nerdy types who aren’t going to make friends otherwise or get laid either way). Bagge wrote me a great postcard that ended, “As for your contention that most Born-Agains are ‘nice people,’ I’m not at all surprised… Most atheists and agnostics are the same way! Take care, P. Bagge.” I think he’s an awesome human being and one of the all-time great cartoonists.

I mean, knock yourselves out. I probably lob enough slagbombs in the course of my “normal” postings to more than make up for my passing on this “official” hatefest, so there you go.

That’s the comradely spirit of hate we’re looking for!

“Well, here’s the thing: If you’re engaged in creative work — and I think most critics have enormous respect for people who are engaged in that work — you are nonetheless submitting yourself to judgment. This is not a progressive kindergarten, all right? It’s not: “You did a nice job, you tried really hard.” What you’re pursuing is excellence, is truth, is beauty”

AO Scott on criticism

Hey Jack- No need to feel embarrassed. In my opinion your letter remains spot on.

While on the subject of criticism:

“If you’re going to be honest with yourself, you must acknowledge that as a critic you have an intellectual and ethical obligation to be outraged by inferior art, to defend your ars poetica with fire or else risk self-immolation by cowardice. If you let by without dispute a failure of language you acquiesce in an affront against literary integrity. The author might be guilty of failure, but when the critic doesn’t call it out he is guilty of something much more odious. Relax your standards in literature and the relaxation of other standards will soon follow.”

The above quote from here.

I am boycotting the Anniversary of Hate and I’ll tell you why over on The Hayfamzone Blog.

http://hayfamzone.blogspot.com/2012/09/good-hooded-utilitarian-bad-hooded.html

Pingback: Hatin’ on Manga at The Hooded Utilitarian

Pingback: Hatin’ on Manga at The Hooded Utilitarian

Pingback: Recently

Pingback: An evil little book? » Spirou Reporter