When Noah announced this hate-fest, I knew immediately that I’d write about Watchmen. What was less clear to me was why—what is it about this book that irks me so much? Why do I silently roll my eyes every time someone starts waxing poetic about Moore’s genius?

The truth is, I should adore Watchmen.

It’s a comic book-loving English major’s wet dream—multi-genre, intertextual, metafictional. So much of what people identify as masterful in Watchmen matches up nicely with the things that gives me incredible intellectual joy in other books, the kinds of thing I try to get my students excited about in class.

Plus, it has superheroes in it. Despite the entrance fee to the comics scholars club being a complete disdain for all things superhero, I really love a good superhero story well told.

So, Watchmen should be a perfect storm of all things that fill me with geeky, intellectual joy. The only problem? I really, really dislike this book. So much so, that I’ve never managed to read all of it, despite numerous tries.

My husband bought Watchmen for me the first year we were married. Comic books moved into my house along with my new husband. I was hooked, powerless to resist the heady combination of new love and Spidey angst. While I would eventually develop my own comic book preferences (I quickly began to favor alternative, autobiographical, talky, snarky books), my comic reading tastes have been forever shaped by the books my husband loves best — Marvel’s superheroes. He loves Spider-Man; so do I. He adores Avengers; so do I. He thinks Kirby is a genius; so do I. He finds the X-Men insufferable; so do I. So when he, and every fanboy I knew, said I should read Watchmen, I fully expected to love it.

But I didn’t. Not even a little. I figured it was me, that there was some context or history or secret code I just wasn’t getting that prevented me from liking the book. But each time I’ve tried — when students ask about it in class, when the film came out, to write this piece — I have the same reactions.

I find Watchmen dull, flat, and, above all, pretentious. And I say this as a person who regularly tries to get students to see how funny Melville’s “Bartelby, the Scrivener” can be.

First, it is ugly. So ugly. I get that aesthetic and artistic quality are in the eye of the beholder. I love Jeffrey Brown’s and James Kolchaka’s styles, and wouldn’t call them pretty at all. My students and I regularly have arguments about whether or not Charles Schulz could draw well. So, yeah, I get that we can enjoy comics drawn in a bunch of different styles. But, c’mon, people. You can’t really enjoy looking at this book. It’s visually crowded, the people are unattractive, the colors are weird. And yes, the visual style is working actively to help tell the story of the ugliness of the world. I get it. But it doesn’t make this book any more pleasant to look at it.

I could let the ugliness slide, though, if the characters were in any way interesting. I feel no connection to these characters. I don’t care enough about Dan Dreiberg/Nite Owl to trudge through his ornithological articles. Laurie Juspeczyk and Dr. Manhattan’s relationship fails to induce any sympathy. Rorschach and Ozymandias are just dicks. I don’t have to like characters to enjoy a story, but I do need to care something about the narrative arc they travel. And in Watchmen, there’s no single character whose life I care enough about to carry me through to the end.

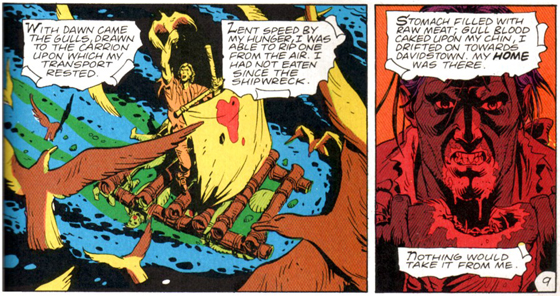

And don’t get me started on that fucking pirate comic. Good god, people!

Most of all, though, I find the books seeming raison d’être, a critique of the superhero concept, to be just plain annoying. I just don’t buy that superhero stories are necessarily fascistic, that enjoying a superhero story makes you necessarily suspect, that we should always be suspicious of do-gooders. The cynicism of the story, and, frankly, the cynicism of many of its fans, is just plain tiresome — not artful, not clever, not profound, just tiresome. Like the hipsters slouching in the corner, smoking American Spirits, harshing on the squares, I find Watchmen guilty of trying way too hard.

So, let’s make a deal: I promise to nod politely whenever you to start to gush about this book, as long as you don’t expect me to join in.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.

Art worse than Jeffrey Brown. That’ll leave a mark.

I’m curious Conseula; are you resistant to any ideological critique of genre? That is, would you also feel that it was wrong to suggest that there might be downsides to romance novels, or horror film, or (for that matter) literary mid-life-crisis fiction? I can see what you’re saying about the value of admiring do-gooders, and that superheroics isn’t necessarily all downside…but surely it’s worth thinking about the consequences of glorifying vigilanties and attempting to solve the problem of evil by hitting it?

I also think that, while Moore and Gibbons do connect superheroes and right-wing politics to some extent, they also connect them to liberal politics. The ultimate criticism is not that superheroes are fascist, I don’t think, but that superpowers link up with (international) superpowers. Watchmen seems more like a directed critique of (especially US) imperialism than of fascism, per se…which seems historically correct (given the superhero rise during WW II) and reasonably insightful about how nationalist ideology works (especially in that Moore/Gibbons are attuned to the way that nationalism has given way to internationalism in some sense…and to why that may not be all that great either.)

“the people are unattractive”

haha

“Like the hipsters slouching in the corner, smoking American Spirits, harshing on the squares, I find Watchmen guilty of trying way too hard.”

Admittedly I did not know where this sentence was going when I saw the word “hipsters”, but was pleasantly surprised that it travelled to the 1950’s, where the h-word originated.

Hey Noah–I’m not at all opposed to critiques of genre. I do find, though, that these critiques are often dismissive of the very idea of genre, as if there’s nothing artistically redeemable about telling a story within already set generic conventions. I find this especially true with critiques of romance fiction (the genre I’m writing about right now). Arguments against the genre often amount to little more than “love stories are simple stories for simple people.” I have little patience for that.

What do you think of Tania Modleski’s book, Loving With a Vengeance? I really like it a lot — and it definitely doesn’t argue that love stories are simple or for simple people, though it treats them with some skepticism….

for me, the Pirate Comic is interesting because it’s based on the idea that in a world with “real” superheroes, stories about them wouldn’t be the most popular form of comic book. i’m not saying it’s genius or anything, i just find that cool. i could defend the Pirate Comic by saying it’s meant to be written like an old EC comic, but i don’t think that will make much difference in the long run.

Like kinukitty and Maus, seems like you wouldn’t hate this if you hadn’t tried so many times to like it. That’s why no one should be forced to read comics they don’t like…

@Noah–I have a vexed relationship with that book because I very much like the idea of a feminist engagement with the genre, but find that Modleski doesn’t deliver much that is critically useful (for me anyway). I find that she is too quick to dismiss the genre and its readers as willfully disconnecting from reality (because fantasy is bad, right?), and that she treats romance as if it were synonymous with Harlequin category books. The difficulty with doing academic work on genre fiction is that there is so much of it, and so much variation, even within generic conventions. You have to read a lot of genre fiction to *get* genre fiction. Modleski strikes me as someone who doesn’t quite get the appeal of romance and I think that’s a not the best place to from which to start genre criticism.

I say all this not having read the book a long while. I owe it a re-read.

@subdee–my expectations for it were high, true, and because of work, I regularly feel compelled to to try it again. Maybe if it were just a random book in a bookstore that I picked up, thumbed through, and put back on the shelf, I would have no opinion on it all.

“I just don’t buy that superhero stories are necessarily fascistic, that enjoying a superhero story makes you necessarily suspect, ”

It’s interesting that you think the story is accusing you of being suspect for liking superhero stories.

I would think, if anything, stereotypical superhero fans found validation in the literary qualities of the book. “Stories about people in tights can be high art! My hobby is not pathetic!”

I don’t know about the fascist thing- the most powerful hero in the book, Dr. Manhatten, is completely mentally out to lunch, not interesting in humanity at all, let alone interested in controlling them.

For many, I think the pretentiousness is a feature, not a bug, its one of the reason I like Moore’s stuff in general. He gives you something clever to play with while also delivering the pulp fun and the pulp violence.

@pallas–I don’t know that I’d go as far as to say the book itself accuses me of me being suspect for liking superheroes. It’s more the cult that has grown up around the book. Then again, I’ve never finished the book. I could be wrong about that.

I don’t find the book clever at all. There’s nothing for me to play with, as a fan or a scholar, or as fan-scholar.

yeah, Moore and Gibbons are no Jeffrey Brown, that’s for sure

further to Milton’s point, I’ll add that I always took the pirate comic to be also making the point that the superhero’s dominance of (one segment of) the North American market is an accident of history, that we could easily have ended up with a different ridiculous genre…magazine articles with titles like “Yarr! Me Hearties! Comics are’t just for kids any more”…Grant Morrison would write a book about how all of human history has inexorably led to the emergence of the idea of pirates…the 80s would see the rise of comics deconstructing pirate comics, making them grim and gritty…

Conseula: “Despite the entrance fee to the comics scholars club being a complete disdain for all things superhero”

Au contraire, after the canon wars genre is the darling of Academia.

Subdee: “no one should be forced to read comics they don’t like…”

This, right here, is reason enough to ban the teaching of literature forever.

@domingos: Not in my corner of academia.

And English departments thrive on making students read things they don’t want to read. I’m prepping Henry James right now, to teach a group of students who will do nothing but complain that they don’t like him. Let’s not write off the teaching of literature just yet.

Okay, i’ll change my comment to “no one should be expected to like a comic just because they read it”.

I don’t think Watchmen is a case of a story that dismisses a whole genre. In fact, seeing Moore’s career before and after Watchmen, it’s hard not to believe that he loves the whole superhero genre. In fact he’s very critical of the whole wave of cynicism and gratuitous violence that Watchmen spawned in the nineties (no pun intended), and he tried to move against that tendency in his ABC books. I think he allowed many fanboys like me to see their favourite genre from a whole different point of view, and I find that valuable in itself.

Also, it’s true there is an element of cynicism in the story, but that’s not the only “colour” in it. There are a few small moments of feeling, throughout the story that reveal that there is a heart behind it.

Like for instance Rorschach. He’s been embraced to pop lore by his badass attituted, but the moments I like best in the whole book are when he quietly acknowledges that he’s someone hard to befriend, and yet Daniel has been a good friend to him, or the moment in the story when he’s inclined to take revenge on the landlady who’s slandered his name, but he refrains because he sees himself in the little kid clinging to the woman’s bathrobe. I think that works very well in a character that until then has been characterized as sociopathic.

And there are many other examples like that that make the story work for me, even leaving aside all the artsy-fartsy elements of page design, literary quotes, visual puns, etc that make it seem so ‘cool’ on first reading.

Of course I can see how it may not be “your thing”, as for many people, but I think kinda unfair that you gut it without finishing reading it. Still, it’s always fun to talk about Watchmen.

You might try reading Modleski again. I really like her…though part of what I like is actually that she’s willing to go ahead and argue that genre really has some unpleasant ideological content, which I think is true (not less true of high art content, which is its own genre — but still, true.) She’s also good about arguing that the women who read it aren’t just dupes though…that there is something there that speaks to their concerns and experiences in a way that doesn’t get discussed in other venues.

I found it very helpful for the Wonder Woman book I’m working on…though obviously that doesn’t mean it’s going to work for everyone….

@Angel–Do you really think I “gut” this book? Really? Somehow I think Watchmen’s (and Moore’s and Gibbon’s) delicate feelings will survive the fact that one random chick doesn’t like their book.

This writing task was a really good opportunity to for me to think about *why* I’ve never finished it, despite numerous attempts. I mean, for a living I regularly read things I’m not overly fond of, so what is it about this book that leaves me cold? It was good thought exercise, if nothing else. I’ve also absolved myself of any guilt I had about not reading it.

I hope that everybody around here caught my tongue-in-checkness. I say this because with the www you never know…

The relationship between academia and genre is weird. It’s true that there is a lot of interest in genre, and a certain level of cache in genre and cultural studies. At the same time, a friend of mine who is an academic felt she had to write under a pseudonym when she wrote an article about loving regency romance, because if it came up on a google search it might well hurt her tenure chances.

I think it’s still a live issue, and one that cuts different ways depending on the department, the exact discipline or sub-discipline,and probably other factors as well.

“I found it very helpful for the Wonder Woman book I’m working on…”

Yes!

“When Noah announced this hate-fest, I knew immediately that I’d write about Watchmen.”

When Noah announced this hate-fest, I knew immediately that someone was going to write about Watchmen. Personally, I was hoping Domingos would. At least he would have read the whole thing. (I’m sort of getting tired of reading critiques where the person hasn’t read the whole book and I have to read a bit into the critique just to find out that they haven’t read the book.)

Well in fairness to me, you don’t have to read far into my piece to find out I haven’t read it, and the piece is in fact about why I can’t bring myself to read it. The fact that I can’t bear to finish it is actually the point. But by all means, mount a campaign for Domingos to write a hate-post about Watchmen. We all want to read that.

The vast majority of pieces in the roundtable are by folks who have read the entire thing.

And, as I’ve said before in these matters, I find it interesting to read discussions by people who are alienated from a work. Alienation from art is a really pretty universal experience in our current pop culture milieu; surely just about everybody who interacts with art has been told to consume something that they find indigestible, for one reason or another. The knee jerk assumption that these (often very strong) reactions are unimportant, or have no critical value, strikes me as really wrong-headed. I certainly enjoy a detailed takedown, as with Isaac’s read on V for Vendetta…but on the other hand, Conseula’s frustration seems useful too, and points to some discussions (the fact that liking do-gooders isn’t necessarily evil) that can be obscured by their very obviousness.

“Alienation from art is a really pretty universal experience in our current pop culture milieu; surely just about everybody who interacts with art has been told to consume something that they find indigestible, for one reason or another.”

The alienation seems to be from preconceived expectations. The answer, possibly, is to ignore or toss away the preconceived expectations. Or ignore the work.

“The truth is, I should adore Watchmen.”

The critic has an idea that she should “adore Watchmen,” which might (can’t speak for her) be the reason she hates Watchmen. Is there really nothing redeeming in Watchmen?

Aja, it seems to me like your preconceived expectation is that the alienation from the work must come from preconceived expectations. Instead of insisting that the work must have something redeeming about it, or that people who don’t see anything redeeming in it must either change their minds or else shut up, why not listen to what Conseula is saying? She feels she should adore Watchmen in part because she’s a superhero fan…and in part because she’s a superhero fan whose tastes are often in sync with her husbands, except in this instance.

Moreover, she’s saying that the things she likes about superheroes are precisely those things that alienate her from Watchmen. That seems like a pretty unusual view, and one which actually takes at least part of Watchmen’s goals — which I think *are* to criticize the superhero genre — seriously. Again, I don’t see why that insight is worthless or out of bounds.

Oh, and like I said, the person who initially talked about doing Watchmen but bailed was Derik. I still hope he’ll get to it at some point; I’m interested to read his take.

“Aja, it seems to me like your preconceived expectation is that the alienation from the work must come from preconceived expectations.” Perhaps.

My problem with this sort of critique is that it tells more about the critic than the book. I don’t read critiques to learn about the critic, but to learn more about the book.

Perhaps I didn’t make myself clear. I am perplexed by my distaste for this book precisely because, on paper, it has so many of the things I like in all books (not just comic books). I am not opposed to metatextual comments on genre(Jennifer Crusie’s romance novels); I often enjoy creators taking clever aesthetic risks with form and content (I’m enjoying Zadie Smith’s new book); I often like things that I initially find difficult to read (Emerson’s essays, for instance). On top of that, all the people whose comic book tastes I came to respect and replicate loved this book. So I was, and still am to some extent, surprised by how much I don’t like this book. Part of it is certainly my weariness of hearing people talk about Moore’s genius (an opinion I don’t share); part of it is also the story the book seems to want to tell. I’m just not all that interested in a cynical superhero story. Or, maybe, I’m just not interested in this one and Moore/Gibbons, I find, don’t do anything in the book to convince me otherwise.

You say put expectations aside, but that’s easier said than done. Frankly, until this was posted, I’ve never met anyone who said they didn’t like Watchmen, and I talk to a lot of different people in a lot of different settings about comic books. Liking this book seems like a universal truth in comics fandom and in comics scholarship. It’s kind of hard for expectations to not build up.

Of course, far be it from me to tell you what you should or shouldn’t get out of criticism (or art for that matter). But, for me, I don’t really see how you can separate work and audience in the way you seem to imply. A work of art is a form of communication; how it is received is a big part of what it means and what it is. A critic is a reader…or, in this case, a partial reader. Knowing why that reader is only partial, or how the reader is alienated from the work, seems to me to tell you important things about the work itself…things that are often ignored.

Again, that doesn’t mean that you have to read it or be interested in it. But it’s why I’m interested in it…and why, on occasion, I print (and am happy to print) reviews like this one.

Since the assignment was to write about something I personally don’t like (as opposed, say, to write about what I’m currently researching or a review of the latest Alison Bechdel book), it seems to reasonable to expect at least a little of me in the piece.

“…it seems to reasonable to expect at least a little of me in the piece.”

Sure, but it’s strange to switch from writing about why you don’t like the book to writing something like this: “You can’t really enjoy looking at this book” or “The cynicism of the story, and, frankly, the cynicism of many of its fans, is just plain tiresome — not artful, not clever, not profound, just tiresome.” (Are the fans cynics?)

Or writing something you think is true, then softening the blow by going against what you say (maybe that only makes sense in my head). “First, it is ugly. So ugly. I get that aesthetic and artistic quality are in the eye of the beholder.” It’s strange to see something like that.

Noah, I see where you’re coming from. I see how alienation from books would be interesting.

By the way, Conseula, how much of Watchmen did you read?

I’ve read 10 of the 12 issues.

Aja…wait…you’re agreeing that you can see my point?

Where do you think you are, anyway? This is the internet, damn it….

Hahahaha. (How many ha’s do I put to not make it a sarcastic laugh?)

Sincere props for reading 10 issues and then not reading the other 2. Personally, I just couldn’t do that; if I get halfway through a book, I have to finish it, even if it turns my stomach.

Interesting how this hasn’t generated as many comments as the Kirby one. I wonder if it’s because dog-piling on Moore has become so common in geekdom yet Kirby has the benefit of being dead and thus not around to potentially say things about the comics and the comics sub-culture that we may not like.

I like Watchmen. I also like this critique. It’s pretty fair.

I do agree with many of the above who say that Moore in fact loves superheroes and their goofiness despite his protestations to the contrary. So do many of the critics who bash superheroes. Our guilty pleasures are pleasures still.

If Watchmen is pretentious, rather than just literary, I might miss that, because I’ve been accused of pretention.

You should go see the V for Vendetta thread.

I’ve typed up and deleted comments on that thread multiple times. But I’ll add them now…

Truth is, Consuela’s criticism is hard to refute, as it’s either true or a question of taste. It’s not obviously wrong or stunt hating as some of the other hate entries have been.

Personally I think focusing on the “multi-genre, intertextual, metafictional” aspects of it is the wrong way to go about liking Watchmen, as really, it’s not so big or clever as it’s been hyped up to be. It’s tricks, clever use of technique, a lot of breadcrumbing for obsessive compulsives (in other words, yer average superhero fan) to find and enjoy.

It’s a book that both revels in and reviles superheroes and I’m not sure how much anybody not that into superheroes will get out of it. It’s also a book set in the paranoia of the eighties Cold War and now dated by this.

What remains are the incidental characters caught up in the superheroics, the kid reading his pirate comic, the newsstand owner, and so on.

Consuela is So thoroughly disengaged from the material that I don’t feel there’s much to talk about. I don’t think It has much to do with the stature of living verse dead creators.

“It’s a book that both revels in and reviles superheroes and I’m not sure how much anybody not that into superheroes will get out of it. It’s also a book set in the paranoia of the eighties Cold War and now dated by this.”

I agree about the dated nature of the book–at least part of disinterest in this book is surely my relationship to Cold War-era paranoia. I experience it as an historic relic more than anything else and I think much of the emotional punch of the book depends on “feeling,” in some fashion, that paranoia. That’s not an artistic failing necessarily, just a inevitable consequence of the passage of time.

I am, though, a big superhero fan (even if being 39, black, and female makes me an atypical one [though that’s a conversation for another day]) and I find the superhero story here less than engaging. I don’t see Moore/Gibbons reveling in superheroes here. There is clearly a lot of engagement with superhero mythology, but both incarnations of the hero team are so morally suspect and corrupt and, in some cases, self-serving, it’s hard to see how this book does anything but revile superheroes. So yes, what you’re left with are the minor characters (the kid and his pirate comic, the newsstand owner, the psychiatrist), but there’s not enough of them to hold me.

@pallas–maybe I missed something about living vs. dead creators? I’ll grant that I’m thoroughly disengagement from this book, but the fact of that disengagement is perplexing and interesting to me.

@John and Aja–I was surprised when I looked back and I saw that I’ve read 10 issues. I’ve read much more of this book than I thought, though I’ve probably read the first 3 or 4 chapters four or five times.

I don’t think it’s true that Watchmen is dated and therefore it’s political insights have nothing to tell us. 1984 is really, really dated (even by its title) but folks still get something about it because totalitarianism and authoritarianism are (at least fairly) permanent parts of the political landscape and modernity. Similarly, the allure of superpower and apocalyptic solutions to difficult problems remains very much with us, as does the tension between the good and the powerful. In some way (like, maybe, the destruction of New York) Watchmen is more relevant now than it was in its own time.

Conseula, I do think you’re missing out on Moore’s love of the superhero tropes. His relationship to them is ambiguous, in that he sees many problems with them — problems I’d argue are very much real, if you think that violence is a real problem — but he’s also a fan. Rorschach is a psychopath, no doubt, but he’s also bad ass…and very sympathetic. Dan and all his toys and his desire to do good is sweet and funny (or at least, it’s meant to be sweet and funny — mileage’ll vary obviously.) Laurie’s great. It’s not an accident that the series has been embraced by superhero fans; it’s a superhero story. In some ways it’s also a superhero parody or critique — but many of the best superhero stories (Captain Marvel, Plastic Man, Superduperman — not to mention Wonder Woman in a lot of ways) have been parodies or critiques. Meta is and always has been part of the genre. If it’s not a part you enjoy, that’s cool…but that’s you rejecting a big part of the genre, not Moore and Gibbons.

Let’s be clear–I don’t reject meta, or cynicism, or critiques of superheroes, or even folks who don’t like superheroes. It’s *this* book I don’t like. Mileage varies and maybe that’s what it boils down to here, but I just don’t think this book is very good.

This is weak.

“There is clearly a lot of engagement with superhero mythology, but both incarnations of the hero team are so morally suspect and corrupt and, in some cases, self-serving, it’s hard to see how this book does anything but revile superheroes.”

Rorschach is at his heart a young child, Laurie just wants to love and be loved, Night Owl II is a Clark Kentish innocent sort of character, Ozymandias just wants to save the world, Night Owl I seems to be a completely good guy.

I don’t see the DC and Marvel heroes as moral or ethical, so I don’t buy the idea that the Watchmen characters are distinct from them.

Ozymandias is in fact, in many ways more heroic than Superman. Lex Luther speaks truth when he says

“Gods are selfish beings who fly around in little red capes and don’t share their power with mankind”.

Superman doesn’t want to help people, he just wants to sell action figures while blandly defending the status quo.

This webcomic is a brilliant take down on the notion that Superman is some sort of moral leader:

http://www.smbc-comics.com/index.php?db=comics&id=2012#comic

Watchmen was published while I was stationed on the island of Okinawa, and thus I never had the chance to read it until the 1990s in anthology form.

For the record, I didn’t like it either.

Consuela’s post seem to echo David E. Ford and Brandon Soderberg’s comments from a few years back on their blog: http://comicsforserious.blogspot.com/search/label/Watchmen

“The problem with Watchmen is that it is difficult for the sake of being difficult–its abstruseness is arbitrary and a serious obstacle to the appreciation of the book.”

“Moore’s assumption is that for someone to actually go through the trouble of putting on a costume and executing vigilante justice, they would of need be pretty ridiculous and pathetic. Not only is this not necessarily true–or even really plausible at all–but it also makes for characters that are fairly one dimensional and devoid of any emotional appeal.”

Huh. It seems fairly plausible to me. Forget putting on a costume; vigilante justice is by definition antisocial. Going out to punch criminals is a pretty odd choice for do-gooding, and I think it’s reasonable to assume that those who engage in it are not moral paragons. (Though Dan and Laurie and Hollis seem like good folks overall.)

“Moore’s assumption is that for someone to actually go through the trouble of putting on a costume and executing vigilante justice, they would of need be pretty ridiculous and pathetic. Not only is this not necessarily true–or even really plausible at all–but it also makes for characters that are fairly one dimensional and devoid of any emotional appeal.”

Right.. cause, like, Batman and Superman are TOTALLY plausible and not ridiculous at all. And totally aren’t ONE DIMENSIONAL CHARACTERS.

I find these attempts to distance Watchmen from other superhero comics (You know, the PLAUSIBLE ones about manly men who fight never ending battles against criminals who break out of jail each week) pretty ridiculous.

The only critique that makes any sense to me is the critique of the art. Gibbons’ characters do kind of look waxy and plodding, and I was never that taken by the actual drawing…though I think the design and layout of the book is brilliant.

I mean…the pirate comic? It’s supposed to be ludicrous and overheated, though it tells us some crucial things about the main plot.

I always feel like people who don’t like Watchmen don’t “get it,” and I don’t mean that they’re not steeped in superheroes…

Of course, I’m sure when I hate something, others feel the same about me/it.

Difference is…they’re wrong!

“Difficult?” I got it when I was sixteen.

———————–

Conseula Francis says:

I find Watchmen dull, flat, and, above all, pretentious. And I say this as a person who regularly tries to get students to see how funny Melville’s “Bartelby, the Scrivener” can be.

———————–

Ah, a teacher. That explains it all, actually.

people, people: she read 10 of the 12 issues. you don’t need to read that far in to know you don’t like something. sheesh!

“I just don’t buy that superhero stories are necessarily fascistic, that enjoying a superhero story makes you necessarily suspect.”

That does seem me like one of the recurring themes in much of Moore’s work. That heroes are bad for us, I mean. That nobody in real life could live up to such a role and that hero worship makes us all apathetic and weak. The whole point of Watchmen, it seems to me, is that heroes are bullshit, utterly impossible not just scientifically but also sociologically and psychologically, and people ought to be ashamed about yearning for them. Because look what results when someone tries to become such a hero in reality. Mass destruction and murderous alienation a la Oyzmandias and Rorshach and the collapse of society via V in V for Vendetta, all while regular people sit on their asses, waiting for a savior instead of affecting change for themselves. Heroes are bad medicine, says Moore.

Which is okay by me. I agree with Consuela so far as that I don’t much enjoy schools of criticism that shame us for enjoying fantasy and boringly parse genre works for ‘problematic’ elements as though they actually believe the chief purpose of art social engineering and propaganda, that wrong-think must be excised out until we’re left with something morally uplifting and true. Basically, I hate when critics come at art from the perspective of scolds. I don’t mind as much when creators do it, as long as they have sufficient talent and craft to make their finger-wagging entertaining.

That’s because I see art solely as a reflection of the author. And since this is apparently what Moore believes…or believed at the time he wrote it, that’s fine. Just like it’s fine when Dave Sims or Frank Miller or Milo Manara tell us what’s going on in their heads through their art. To me it’s not about agreeing with the creator or having my own beliefs buttressed through them. It’s about sharing their vision, however perverse, for awhile.

Anyways, Moore seems like a smart socially conscious kind of guy…and he also seems incredibly pretentious and something of a bitter pill who enjoys finding flaws in even the most frivolous of things (IE, super hero comics). But that’s just his art of course. He may be something else entirely in real life. I don’t know as I’d like him as a person or share his worldview but I like reading him, and only the latter matters to me. A shame the OP didn’t enjoy Watchmen but that’s no crime. Art is like ice cream and not everyone enjoys every flavor, but I hope we can all agree that both exist to bring us pleasure and little else. Nothing in art should ever upset you. It’s just some guy/gal making up crap with whatever’s available in his/her head. All we can ask is that it be entertaining and well-crafted IMO. It doesn’t have to be true, enlightening, or improve us as people. Art, like the heroes in a Moore story, isn’t strong enough to shoulder that burden. That’s up to us.

“but I hope we can all agree that both exist to bring us pleasure and little else. Nothing in art should ever upset you.”

Nope, we can’t agree. Art frequently has a major, serious impact on the world — whether for good (Uncle Tom’s Cabin) or for ill (blackface caricature.) Art’s communication; as such it has the possibility to change people’s minds and hearts. That’s why people argue for it and are interested in it — that’s why you took the time to write a post insisting that art doesn’t matter and shouldn’t be treated morally, and then concluded by explaining how we should all treat art and why your viewpoint is the moral one. You may dislike scolds, but in insisting that art must be for pleasure and little else, or that folks are foolish for treating art as if it makes a difference, you’re being a scold yourself (which is fine! I don’t have any problem with scolds — who I don’t think are scolds, but simply people engaging with the moral, political, and yes, aesthetic issues that art raises.)

Creators don’t exist in a vacuum. As such, no art can be simply a reflection of the creator, because the creator isn’t simply a reflection of him or herself. People are tied in innumerable ways to their societies and cultures; it’s really hard to say where the individual ends and the people who they’re talking to begin. And, in any case, if we were all such hermetically sealed icons of romantic individualism, it’s unclear how we could even talk to each other; what would there be to say? If art matters, it matters; if it doesn’t, it doesn’t. But I don’t see how art can be (potentially) an entertainment if it can’t be something more. Entertainment is communicated in the same way, and along the same channels, as education, politics, morality, love, and hate. You’re either talking to each other or you’re silent. If the first, you can talk about anything; if the second, you can’t talk at all.

I didn’t like/was disappointed by Watchmen as well. I went in wanting to like it a great deal because of the cult status. And I did love it for about the first quarter. Intrigue! Mystery! Darkness! Compelling characters! Lots of historical back story!

But the pervasive puritanical sense of guilt that pervades much of US comic culture got to be all too familiar (yes, even though Watchmen was written by a Brit), the pitfalls of superhero-dom became unappealing (Manhattan — sorry if I’m getting the name wrong — seemed much too unbalanced an aspect in the face of the gritty/real take on “super”heroes.)

Having to read all the pirate side story was a chore. Truth be told, it didn’t occur to me while reading the book why that side story was in there, and it was so mundanely unpleasant that I didn’t care to find out.

Finally, most importantly, THE *big* plan Ozymandias was hatching? The whole impetus for all the mystery and subterfuge?… Faking an alien attack to artificially rally the people of Earth together? Really? *That’s* the stunning revelation? To me: so, so. Wait… SO lame.

I never saw the movie because of how disappointed I was by the book. As much as I can indeed see the genius in it, I see as much of the puerile.

Thank you.

Hai. I just read the first line, was too busy to read the whole story, just wanted to add that I like the concept of the movie/comicbook Watchmen, I like superheroes, but the violence and rape/blood/etc. is way too shocking. I was sexually assaulted as a kid and my bf showed me his favorite movie, watchmen. I started crying when the raping scene started, since then, I hate hate hate it. Especially because the woman feels bad for ‘Poor Eddie.’

I am a very open-minded person, and when I opened this article I was hoping to see some well-argued opinion and some bad points of one of my favorite novels.

I have to admit, though. This is one of the most masturbatory, outright ridiculous articles I’ve ever had the misfortune of reading. I hate you because you induced me to read this, and it pissed off so much that now I have to write it off and waste more time.

First off: Watchmen isn’t supposed to be visually impressive. It wants you to tell a story, and it wants to stay true to real life. If you read comics to fulfill your superhero fantasy and dive away from the real life, I understand why you hate it since it is down-to-earth. No flashy colors and black-white morality. The ending is ambiguous, not happy. Not only that, also one can argue that art style is actually unique and satisfying: The panels are metricized (9 panels per page, pretty much the whole story), symbolism and hidden details can be found everywhere, and the expressions are beautifully portrayed. A cringe-worthy moment: “People are unattractive”. What the hell, are you 12?

Secondly, you seem to have missed the point by a long shot. Laurie and Jon’s relationship isn’t supposed to induce any sympathy. She’s seen as a fucking whore by pretty much everyone, this is in fact lampshaded in the story. Jon, to paraphrase Sally, is a H-bomb that needs to get laid. Rorschach went insane and become a psychopathic killer. Ozymandias is narcissistic and self-important. The Comedian thought he figured out what human nature was all about and decided to become a parody of it, only to break down and ultimately die after he learns Ozymandias plans. When you see Nite Owl II for the first time, you certainly think he’s the most human and normal of them all, but after that you learn that even he has his own insecurities: he’s fat and impotent. If you fail to see how this is supposed to be a depiction of the human condition, you are a very superfluous person and you might as well hate on Shakespeare. Oh, that wouldn’t make you cool, would it? Come on, call me off for comparing Watchmen to Shakespeare. Make your professors proud.

And third: My bad, there isn’t a third. Apparently two “arguments” (for the sake of argument, let’s call them arguments) is all you can come up with to justify your hate on one of the most significant and well-written pieces of literature from the eighties. Someone HAD to hate it, didn’t they? It’s like you said in the beginning: You hate it, but you didn’t know why exactly you did. Now you have your answer. :-)

You finish by blatantly giving away that you have no idea what the comic was about, and what Moore was trying to expose. I don’t like the guy but he’s not nowhere near as cynical as you make him be. There are indeed do-gooders in real life, but I can see them doing anything except putting up a costume and doing justice with their own hands. Moore was only portraying how superheros would be in real life. You don’t have to hate superheros and superhero stories to see his point. He’s written Batman and Superman stories, I’m sure he enjoys mainstream superheros and isn’t suspicious of do-gooders. I myself am a very optimistic person and I don’t know any Watchmen fans that are extremist cynics.

Oh, and by the way, you don’t have to be polite and play it cool, you know? In fact I’d love if more people would express their edgy opinions on critically acclaimed works as eloquently as you have done here, so I know I can completely disregard their say on anything from then on. Have a good one.

@ Zero–that’s an awful lot of words for something you’re not going to engage. Thanks for the close read. It’s entirely possible I am 12.

The real reason to hate Watchmen is that everybody goes on about it fuckin’ endlessly.

BTW: Your husband has terrible taste.