I

The standard line on The New Yorker’s cartoons is that they are the first thing most readers turn to when they get their hands on a new issue. Well, I don’t. I actively try to avoid looking at them, difficult as it is. Peppered through articles of serious journalism, strong criticism, and pieces of often very good fiction, they are meant, I suppose, to induce some kind of alchemical understanding of what it is to be a New Yorker, or — failing that — a New Yorker reader. To me, and I suspect quite a few others, they remain obnoxious non-sequiturs, like tired notch-notch, wink-wink routines insistently dropped into an otherwise lively family conversation by your borderline senile uncle.

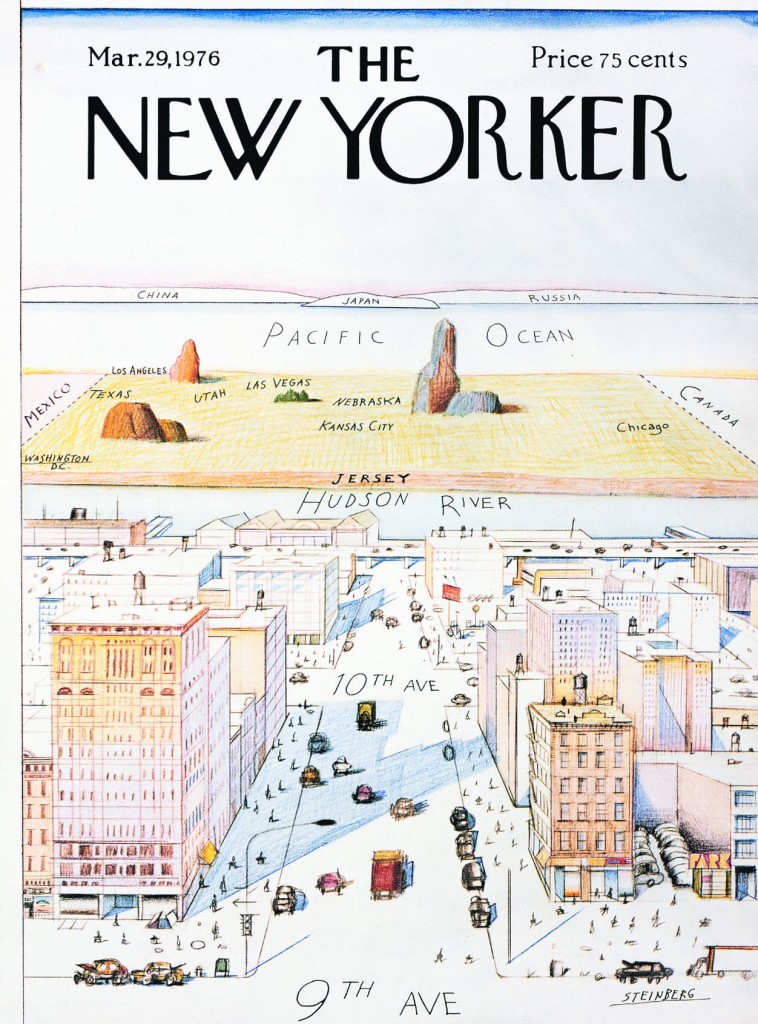

The other oft-repeated line about the New Yorker cartoons is that a lot of people ‘just don’t get them,’ with the frequent corollary that this is part of their point, and once you realize it, you feel ‘in’ with those in an authentic New York state of mind, I suppose — you know, those whose worldview Saul Steinberg summed up so incisively in what remains arguably the most famous New Yorker cover of all time.

Thing is, if you actually review a substantial selection of cartoons from the magazine’s octogenarian history, the vast majority of them are totally straightforward. You understand the joke. No Mystery. Only in the last decade-and-a-half or so has editorial showed a preference for a certain brand of light absurdity that at times borders on the impenetrable. Nothing wrong with absurd humor, but the problem in this case is that one of the main strengths of cartooning, clarity, is sacrificed in a vain bid for ingenuity.

This more or less corresponds to the period in which hack cartoonist Robert Mankoff has served as cartoon editor. He has been a hugely successful manager of his part of the New Yorker brand, merchandizing the cartoons through the online Condé Nast Cartoon Bank to the tune of millions of dollars a year, as well as editing the monumental Complete Cartoons of The New Yorker (2004), which bundled all 68,647 cartoons thitherto published in the magazine on two CDs. Bonus info: he has had over 800 cartoons published in the magazine.

Mankoff furthermore is the instigator of the popular New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest. And far be it from me to suggest we deny people their fun, but the concept is revealing of his editorial philosophy, where the visuals become so generic that they accommodate just about any joke. Absurd or not, the naughts have been the nadir of New Yorker cartoons in every respect, from idea to execution. More than ever, one suspects that the notion that they harbor some elusive brilliance available only to the in-crowd really just euphemistically expresses a general puzzlement about how unfunny they are. As in, ‘can they really be that bad?’

We are, after all, talking about the Holy Grail of American cartooning. The one publication countless cartoonists would hack off their non-drawing arm to be published in. The New Yorker, somehow, has managed to convince a wide, generally discerning and highly cultivated readership that their cartoons represent the acme.

Try as I may, I have been unable to assimilate this View from Ninth Avenue. Reading through several thousand of the cartoons assembled by Mankoff in his 2004 book, I cram to understand it. From the very beginning in 1925, the New Yorker cartoons as a rule have been unambitious, unimpressive, and unfunny. Not to mention frequently sexist. As a platform for cartooning, the magazine has (with a few exceptions, to be addressed presently) been a deadening force at the heart of the art form, smothering the field in bourgeois mediocrity.

II

In a 1937 article in the Partisan Review, The New Yorker’s bête noire of the time Dwight McDonald — later a significant contributor to the magazine — criticized the cartoons for their “Jovian aloofness from the common struggle”, identifying “…something inhuman in [their] deliberate cultivation of the trivial.” This critique was part and parcel of McDonald’s, and the Partisan Review’s, ongoing criticism of the The New Yorker more generally. McDonald concomitantly described the typical writer for the magazine as having “given up the struggle to make sense out of a world which daily grows more complicated. His stock of data is strictly limited to the inconsequential.”

This is not the place to enter into the long and complex history of The New Yorker and its critics. Suffice it to say that any institution, cultural or otherwise, that achieves this kind of success and influence will be met with criticism — and indeed McDonald’s words are echoed in those of many a critic of the magazine since. But whatever the problems of ‘New Yorker fiction’ as a phenomenon, of the blind spots exhibited by the magazine’s critics, or of its at times timid or problematic treatment of important political issues — most recently perhaps the 2003 invasion of Iraq — it is undeniably one of the publications of record in all three areas.

In other words, McDonald’s critique, however accurate it might be in diagnosing a fundamental aspect of founder Harold Ross’ vision, does not render justice to the ambition and quality of the magazine, then or now. Where it does ring true, however, is in its characterization of the cartoons, then and now.

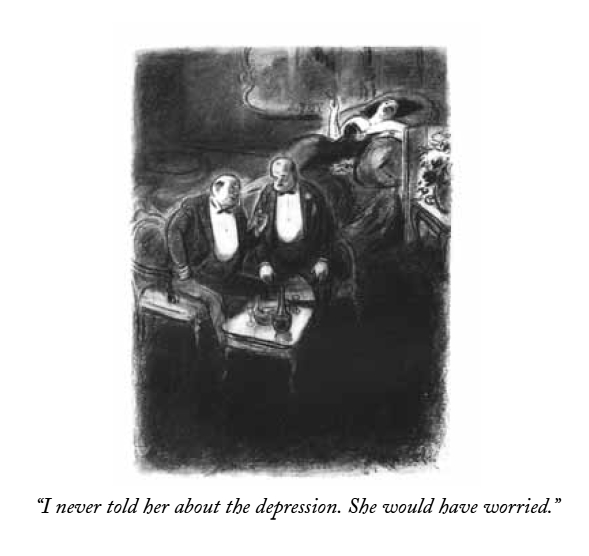

Reading the introductions to each decade of The New Yorker’s publication history in Mankoff’s Complete Cartoons, each written by a different author connected with the magazine — from Roger Angell and John Updike to Lillian Ross and Calvin Trillin — one is struck by their apologetic tone. They are forced to acknowledge the obvious: that The New Yorker’s cartoonists almost never managed to comment intelligently — or indeed at all — on the important events of their time, be it the Great Depression or the Second World War, the civil rights movement or Vietnam.

This was all in keeping with Ross’ sensible if not unproblematic vision that The New Yorker would “not be iconoclastic”, marketing it as he did to “intelligent and discriminating men and women who appreciate fine things and can afford them.” While it would be a fair question to ask why the magazine has shied away from political or otherwise editorializing cartoons, especially when their other content is much less hands-off on such matters, this in itself is not the problem. The point is that choosing gags as your calling does not let you off the hook. Major national and world events belong as much to the social sphere (the domain of gag cartoons), as it does the political or economical. The New Yorker, however, was content with serving up endless iterations of two guys in a bar, desert islands, and bosses and their secretaries — a dull superfluity of safe inanity.

III

The gag cartoon is a difficult discipline. The trick, of course, is to make the reader laugh. The joke’s the thing. And there is no accounting for humor, which makes accessing your own in its purest form the noblest avenue of expression for the cartoonist. Not to mention the funniest. It is not so much that there are not a fair amount of fairly funny jokes in The New Yorker, but rather that they are almost invariably of the generic variety, with cartoonists content to act as warm bodies on the mic stand, interchangeable and disposable. Too few of them present a truly original, unexpected, idiosyncratic, intelligent, or imaginative point of view, and judging from just how consistent the magazine has been in this regard, it seems editorial has rewarded them for thinking inside the box.

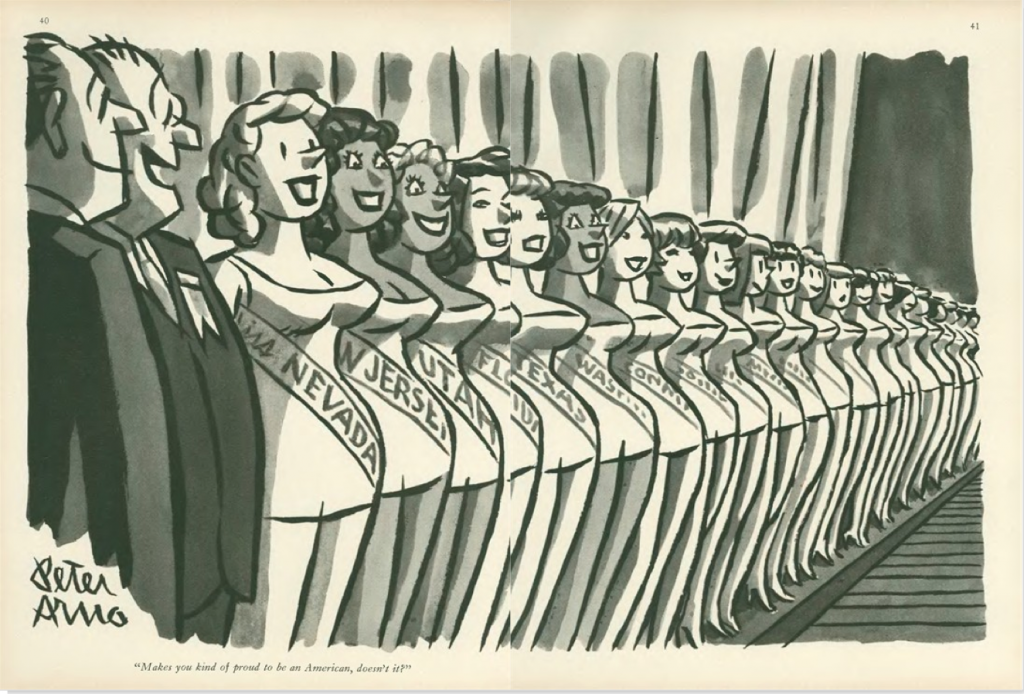

Let us forego the banal swill that bulks up the bibliography and focus on some of the canonized artists; the best the magazine has had to offer, according to public opinion. First there is Peter Arno, the quintessential dandy cartoonist, a kind of real-life Eustace Tilley, cuffs stained with india ink.

No doubt, Arno is one of the great visual stylists of American cartooning, and arguably the most effortless major graphic contributor to the magazine. His cartoons are master classes in composition and narrative, at times carrying an almost abstract beauty in their distribution of forms, light, and shade. Yet, his visual characterization, while extremely precise and frequently funny, is invariably trite, serving up conservative stereotypes spritzing the safe clichés of the masculine bourgeoisie — from Martini jokes to silver fox slickers ogling chorus girls. Very little of Baudelaire’s flâneur remains in his and his various gag writers’ myopic, self-sufficient perspective.

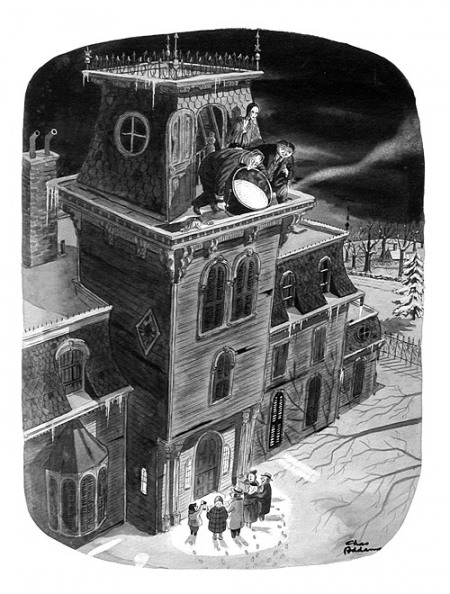

Another icon is Charles Addams, possessed of a genuine yen for the absurd yet ultimately toiling it in service of warm reassurance. His earlier cartoons boast some inspired ideas and occasionally reach toward the surreally unsettling, but by the time he had established the Addams Family, those lovable munsters in their plush Halloween mansion, he started descending irrevocably into comfy family camp. Worst is the utter lack of visual ambition — one plump Addams character pretty much substitutes for another, any signs of individuality listlessly muddied up in drab wash.

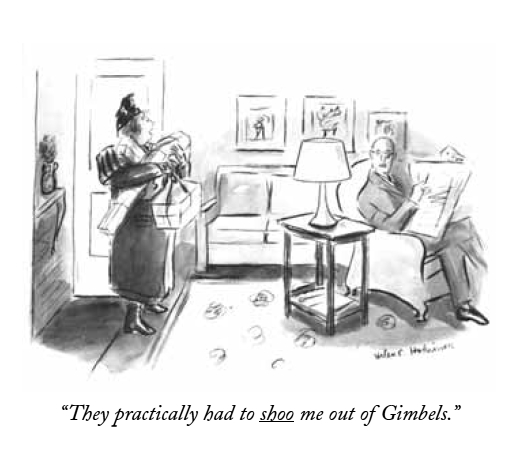

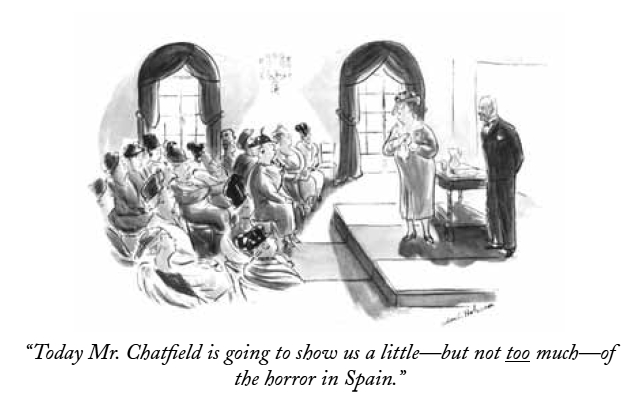

Helen Hokinson suffers from similar problems of visual realization. Drawing her characters small and indistinct, it is frequently hard to glean anything significant, relating to the gag or otherwise, from their facial expression or body language. A pity, because her wit (or that of her gag writers) is sharp, if limited in scope — lots of rotund society ladies, lots of hat, dress and jewelry jokes. Her irony cuts a little deeper than that of most of her peers, but dissipates with a dispiriting ‘aw shucks’ fizzle.

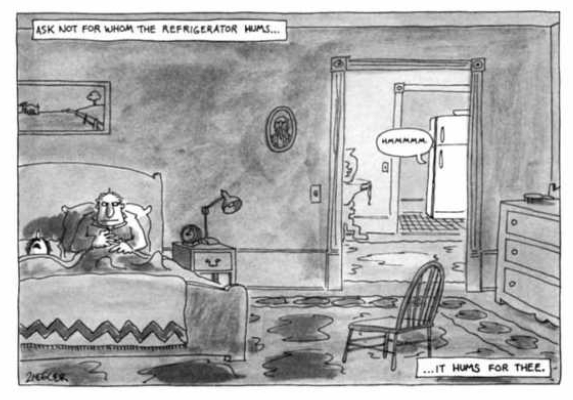

Of later comers, Jack Ziegler is one of the most prominent, I suppose both for his versatility and consistency in terms of joke content, but also, surely, because he is somehow quintessential. Beyond the shoddiness of his rendering—more complex of course, but essentially no different from the arid cartooning of a Scott Adams — he lacks a core: emotional, personal, what have you. To him a joke is just a joke, and he can be relied upon to makes us laugh and forget, issue after issue.

Then there’s Roz Chast, The New Yorker’s current cartoon fig leaf for artistic respectability. She is to be commended for introducing into the magazine a kind of poetic whimsy previously unknown, and for deprioritizing the punchline in favor of more ineffable humors. Unlike most of her colleagues, she actually has a personal voice, but it is never particularly revealing: a step beyond the imaginative dazzle, it is cute and cosy, keeping anything difficult at arm’s length.

This complacent tone is apparent more than anywhere else in the lazy drawing, which remains unimproved after more than thirty years. The telephone doodle charm only goes so far, because the small, overcrowded, inarticulately composed, and sluggishly washed drawings rarely contribute more than a very general — if persistent — sense of caffeinated giddiness, ending up placeholders for ideas worthy of a more articulate cartoonist. It’s like watching Ted Rall impersonating Lynda Barry.

Next to Chast, Bruce Eric Kaplan is the seeming exception that proves the rule that current New Yorker cartoonists all lack personality. His graphic style is his big draw: everything is drawn as if by etch-a-sketch, centering on a supposedly existential emptiness. It is indeed spectacular in the dull context of the magazine, an easy standout, but it’s a shtick: the cartoons are interchangeable, their links to individual jokes tenuous at best, and the general sense of alienation is unmodulated to fit the content. The same idea executed ad nauseam.

III

I could go on, but the point should be clear. These are highly overrated cartoonists, elevated by their august platform. And keep in mind that they are the wheat to the vastly more abundant chaff. One might argue that gag cartooning is simply not suited to the kind of artistic expression lacking in the pages of The New Yorker, that I’m setting the bar too high here, but besides questioning the wisdom of focusing so one-sidedly on gags at the expense of other forms of cartooning, you could point to Mad Magazine — a publication whose cultural impact, however different, is commensurate — as a much more reliable source of quality humor cartooning, despite its own faults. The critically overlooked Don Martin easily trumps any of the above-mentioned for originality and plain laughs. As do a number of cartoonists working in similar formats never — or rarely — published in The New Yorker, from H. M. Bateman and Virgil Partch to Basil Wolverton and Gary Larson.

In a way, however, the most damning factor is that The New Yorker harbored a few cartoonists whose example — if it had been internalized instead of merely idolized by editorial — would surely have helped shape a truly innovative cartoon platform. One is William Steig, a cartoonist of fertile imagination, a well-honed instinct for portraying the human animal, and — as he matured — a nervous line crackling with personality. One might argue, however, that he did his best work elsewhere, primarily in children’s books.

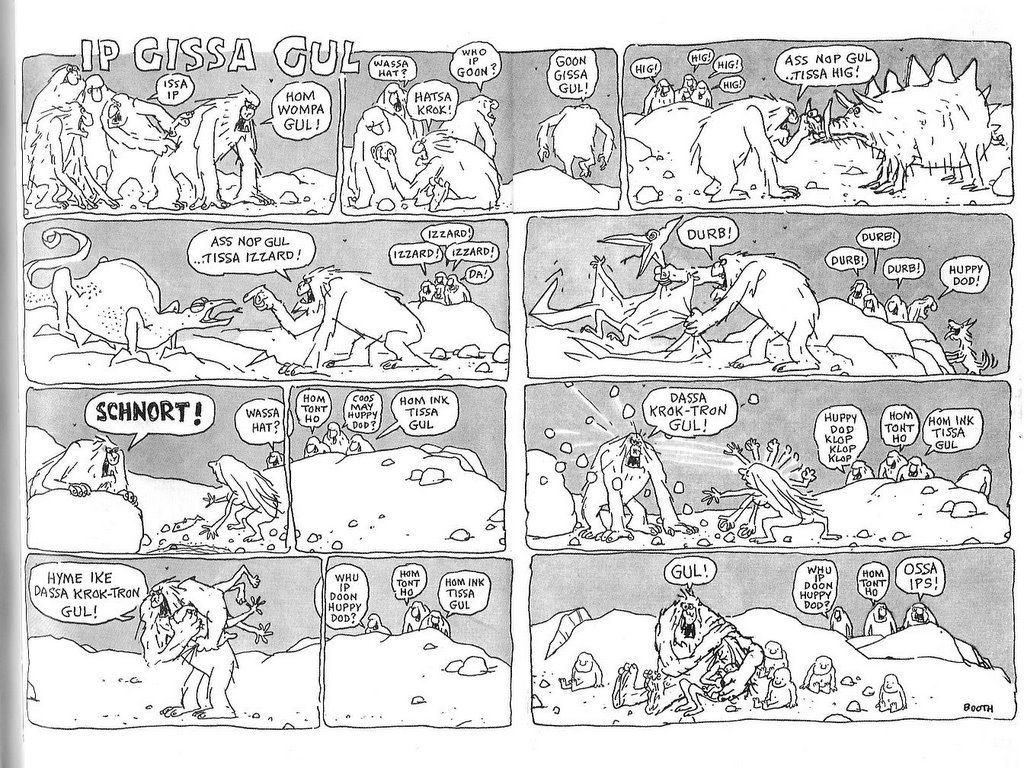

A bright spot in the dim latter half of the William Shawn years was George Booth. Although not the most gifted gag writer, his anarchic humor as manifested in his ratty line, and trademark rat-like dogs, is an unexpected delight in the murk that is any given issue’s cartoon selection. At times, he comes off not a little unhinged, not unlike the aforementioned Don Martin. More of his kind would have been a help, but not enough in itself.

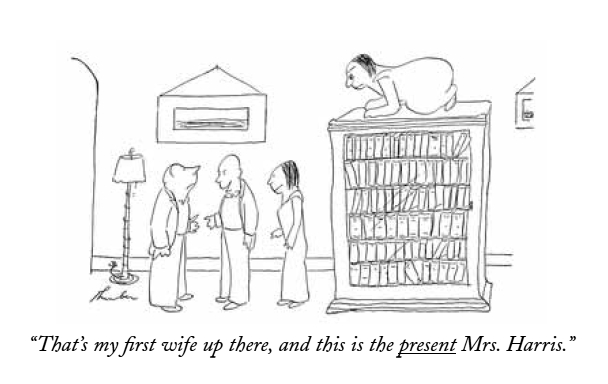

The true paragons — of course, I suppose — are James Thurber and Saul Steinberg, however. The half-blind Thurber was a natural cartoonist, possessed of a genuinely original vision that included as acute an eye for human behavior as any of his fully-sighted peers, condensed on the paper in sprightly notation. His treatment of his main theme, gender, may initially seem a little banal until one notices the disturbing irrational undertones pushing at the edges — the ex-wife lurking on top of the bookcase, the seal behind the bed, the sudden fencer’s head-lop. Thurber’s is a cold world, and the gleam in his live eye is humor.

The strange thing is how little his approach came to shape The New Yorker’s cartoons. Of course, few cartoonists can be expected to be as original, but he remains an example of what can happen if one admits and nurtures the personal sensibilities of a gifted cartoonist. Although this was initially Thurber’s good friend E. B. White’s doing, Ross clearly grew to appreciate Thurber, who became one of the magazine’s graphic constituents (and literally part of the architecture by way of his graffiti, a piece of which has been transposed into an oblique corner of the current offices in the Condé Nast building). It is hard not to see it as an editorial failure that his example wasn’t followed.

Except with Steinberg, one of the century’s great cartoonists. Although just as unique, he became much more central to the magazine’s graphic identity than Thurber, and his influence on it remains much more pervasive, if in all the wrong ways. A cartoonist of brilliant facility and mind, he unassertively situated himself in the continuum of modernist art, but with a distinctively post-modern sensibility, Steinberg was the quintessential meta-cartoonist. He elevated the discussion of what cartooning is and, by consequence, the significance of The New Yorker to the art form.

Now, I must confess to some reservation vis-à-vis Steinberg. It’s easy to appreciate his cleverness and I do love his line, but I largely agree with Tom Lubbock’s critique that there is something too controlled, too detached, too safe about his cartooning, which is obviously witty and intelligent, but neither really funny nor really troubling. This takes us back to the central problem with The New Yorker’s cartoon tradition and how Steinberg validates its ethos, despite his outsize talent: New Yorker cartoons are often witty, if rarely intelligent; they are occasionally funny, but never troubling. They perpetuate an escapist bourgeois utopia, detached, controlled and safe.

What’s frustrating is that it could have been different. The New Yorker could have exerted the same level of ambitions on the part of their cartoons as they developed with regard to journalism, criticism, and fiction. Ross’ project to endow the magazine with a strong graphic identity was smart and it worked, not the least because of the often excellent illustrations and the famous covers. But the cartoons remain a monument to mediocrity, a would-be canonical example of wasted opportunity, were it not so bafflingly extolled as a high watermark. As it stands, I don’t doubt that The New Yorker would have been better off without them, and in my darker moods I feel as if the art form as a whole would have too.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.

The comparison with Mad seems particularly telling. Not just Don Martin, but Sergio Aragones, Al Jaffee, even Dave Berg — whether or not you think they’re great cartoonists, they all had distinctive styles and were given room to explore them. I wonder if the difference is that for Mad the cartooning was more central, whereas it’s always been more of a decorative side-note for the New Yorker?

The difference between Mad and the New Yorker is that the former has always been crassy commercial, while the latter has always been a refined and genteel part of the New York intelligentsia. A wry, restrained grin at the sad absurdities of life is the worst that is allowed in those circumstances, while great cartoons need emotion.

Now this is a worthy target.

Sorry but I strongly disagree with some of your assessments of the aforementioned cartoonists. Your expectations are personal to your own needs. Cartoons are like music, they don’t have to be anything nor answer any questions. If they do, great. If they raise questions better. But to make them accountable to documenting 20th century history or fulfilling your criteria of the cartoon curve seems “inside the box.” Do you only listen to protest music? To compare work from 80, 90 years ago is like lumping in classical music with the Beatles. Our society’s sense of humor is not completely different by now? To me, that is lazy and unfair to late cartoonists of past. Finally, let me state in full disclosure that I do do cartoons for the New Yorker as well as other places worldwide. So I do have a dog in this race. And I’ll agree with you not every cartoon is hilarious but thank goodness we all don’t agree on which ones.

Hey Bob. Of course Matthias’ opinions are his opinions…but I don’t think your defense is very effective. Matthias criticizes them for aesthetic timidity, and for failing as cartoons focusing on society, not politics. If we’re able to say today that Shakespeare was great, I don’t really see why it’s wrong to say that the New Yorker cartoons (which are much closer to our time, obviously) aren’t so good.

If you want to defend some of the particular cartoons Matthias dislikes, that’d be great. But a general claim that we can’t criticize old things, or that the cartoons don’t need to be political — when Matthias didn’t say they did — seems unconvincing.

Finding good cartoons in “The New Yorker” is like panning for gold in gold country. It may take a lot of work, but sooner or later you’l find some nuggets.

I purchased “Complete Cartoons of The New Yorker” and nearly went blind looking through the collection. But I can’t remember if I looked through them all. That may be an indication of the blandness and interchangeability of the majority of the cartoons, or it may just be that the cartoon overload numbed my brain.

I’ve never supported myself by cartooning, but I’ve been a cartoonist for about 45 years, and have sent ot a few gag cartoonist during that stretch of time.

I sent “The New Yorker” one about five years ago because it was funny in a wry way, and was set in a Times-Squarish backdrop. It was rejected, but I STILL think it’s funny.

Here’s the reject: http://home.comcast.net/~russ.maheras/Asteroid-72dpi_copy.jpg

Hey Bob, thanks for replying, and for doing it so civilly, after my admittedly harsh piece. I think Noah’s more or less answered for me, so I just wanted to say that I agree with you that cartoons can be like music and don’t have to answer for themselves according to one specific set of criteria, but I had hoped that that was actually what was conveyed in my essay. The point about their engagement with social issues of their time is just one criticism, but if you check back I hope you’ll see that it’s not a demand. What I would have liked to have seen, and to see, in The New Yorker are cartoons that express more of a personal vision, a good to high level of craft, and which are funny. Pretty much. I don’t see much of that in the back catalogue, and I certainly don’t see it today — as I wrote I think the cartoons are, on average, worse than ever, plus they feel almost totally anachronistic in a way I guess they didn’t use to as much.

As for the comparison with Mad, Noah and Martin, I think you’re both right, although I disagree that The New Yorker’s chosen position and target audience precludes challenging, original cartooning.

Russ, thanks for sharing!

YES.

Well, this is certainly a discussion hard to capsulize in a comment box and I don’t claim to be a scholar in humor or this publication but I don’t want to be rude and give the impression I left the room in a huff.

Yes, Shakespeare stand the test of time. But surely he ws funnier back then. Secondly, my conclusions were based on your adjectives; just one example; calling Mankoff a hack. His book and the work contained in it alone, The Naked Cartoonist, demonstrates the force he is in this field and that’s hard to debate. Specifically,your request to see cartoons “that express more of a personal vision, a good to high level of craft, and which are funny.”…I ask you to search in that catalog or easier the Cartoonbank.com, just off the top of my head, Bob Weber or Charles Saxon. Present day? Granted, in the current issue there be may a spectacular range of funniness, the highs ARE bright (and be my guest to critique mine, it’s the second cartoon on pg 38. It’s not even my favorite in the issue but I promise I used some personal vision and a good to high level of craft.).

I was out all day but at lunch I engaged in this conversation at a diner and handed out four recent issues of the NYer to the foursome. All are college educated and two are writers for the NY Times. I asked everyone to pick their favorites and the one they thought were the turkeys. Some people’s worst were other people’s favorites. That’s how cartoons get in. They’re picked by humans. Thanks for listening to my two cents.

“But surely he ws funnier back then.”

It’s hard to say. Shakespeare’s comedies are really kind of amazingly funny today. Some of the jokes can get lost a bit in translation, but a lot of it is slapstick and dick jokes, and those are things that never grow old….

“Absurd or not, the naughts have been the nadir of New Yorker cartoons in every respect, from idea to execution.”

I don’t agree that the magazine has historically been a failure cartooning-wise. But I do agree whole-heartedly that overall in recent years the gags lack the bite that they used to have.

Matthias, do you think Francoise Mouly deserve any of the blame for this?

If I may, Miss Mouly deals solely in the NYer cover selections.

Shakespeare is a genius and SO many great expressions you would never think of are still used today. I love Shakespeare (and regret I picked that as a point to challenge). But it’s not possible to compare his humor and I don’t find him hysterical like a good Danny Shanahan cartoon or Alex Gregory cartoon. http://www.condenaststore.com/-sp/You-re-right-things-are-funnier-in-threes-New-Yorker-Cartoon-Prints_i8540123_.htm

If you pick up 68,647 of anything most of it will be crude.

Well, yes, but my argument is that there has been an overall editorial problem. Also, this is the reason I chose to critique, however briefly, a selection of the best-regarded (and, frankly, best) cartoonists the magazine has published, instead of a bunch of lesser hands.

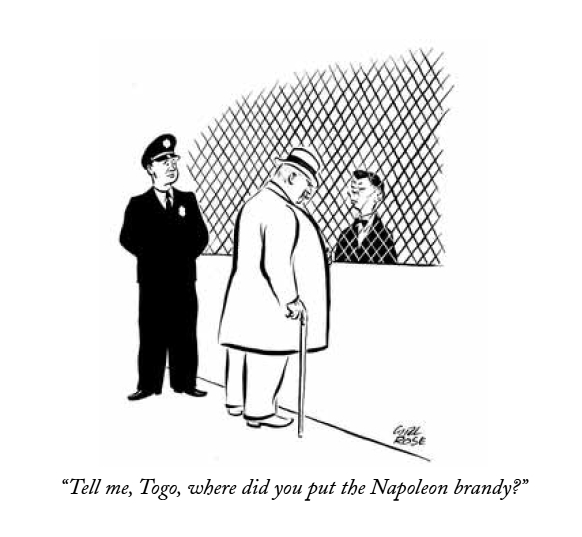

Also, absurd as it is with this microscopic a selection of the whole, I’ve tried to be representative, mostly showing fairly high quality work from the cartoonists I talk about, and also — for example — tempering the Gilbert and Sullivan racist jab at the Japanese with Carl Rose’s really quite excellent cartoon from the same issue, published when tempers were understandably high.

Regarding Mankoff, he clearly is “a force in his field”, but to me that’s more due to his work with the cartoon bank and his activism, and — inevitably — his editorship at the New Yorker (even if I think he’s terrible at it). But none of that makes him a good cartoonist. I mean, just look at the one I posted. For those unfamiliar, I assure you that it’s quite representative.

No critique of Mouly is implied. I not necessarily wild about all the choices she’s made, but overall she’s been a great cover editor. In any case, my article is not about the covers.

Well done, Matthias; overall, I tend to agree with some reservations. For example, we should bear Sturgeon’s Law in mind: 90% of everything is crap.

I once had a volume of cartoons celebrating 30 years of the New yorker, and they’d obviously cherry-picked the best of 3 decades.It was magnificent! And funny!

Personally, I think they made a big mistake, under Shawn’s editorship, in banning writers other than the cartoonists themselves from contributing gags; under Ross, often the idea came from such comedy masters as E.B.White, Robert Benchley, S.J.Perelman or James Thurber.

Disagree about Addams, agree strenuously about Roz Chast.

The comparison to Mad seems to be a bit apples and oranges; perhaps it’s more instructive to look at other magazines such as Esquire, True, or Playboy…even at Punch, which really revitalised itself over the ’60s.

It’s ridiculous that great gag cartoonists such as Virgil Partch or Ronald Searle weren’t part of the NY stable!

Agree that the present period is particularly dire…

Bob Eckstein, thank you for commenting so graciously.

I think covers like this one are an embarrassment. I don’t think an image like that would’ve ever passed muster in the old days. Even in the Tina Brown years. I’d say overall the post-RAW cartoonists have not held up the same standards of the magazine of old.

“you could point to Mad Magazine — a publication whose cultural impact, however different, is commensurate — as a much more reliable source of quality humor cartooning”

That’s highly dubious. MAD could have its virtues. But for decades I think it was editorially stagnant and wedded to formula, the talents of the cartoonists notwithstanding. It wasn’t until the mid-to-late nineties (or so it seems to me) that it finally got back some of that spark.

And are “laughs” really the most important goal for a cartoon?

Another problem is what else can you compare it to? Alex mentions the sixties, but in the decades after that what else was there? Playboy always had cartoons of course, but the editorial strictures squeezed the life out of most of the cartoons.

Actually, Steven, I think that cover’s pretty neat! Different strokes…

In the 70’s National Lampoon was a terrific source for gag cartoons, notably those of Rodrigues…Penthouse, Omni and (yes) Hustler featured superb stuff. In the ’80s and early ’90s, Spy magazine was pretty great.

This isn’t even to mention overseas gems like Britain’s Private Eye or France’s Charlie Hebdo…

Actually I guess the New Yorker looks pretty sickly.

True, Playboy

(oops, web hiccup)

True, Playboy really compromised itself with kitschy, fake-sexy leering illos, but it still publishes good stuff by Gahan Wilson and R.O. Blechman, among others…

I kind of hate that cover. The intellectual cutesiness is just like sandpaper on my eyeballs.

It seems very New Yorker, though; don’t know that Clowes is letting the side down so much as keeping on keeping on.

Well, I think you may hate it because you’re more familiar with the Sci-Fi tropes involved than the average NY reader is.

It’s true that apt comparisons are hard to come by. The reason I chose Mad is because it’s a cultural institution of comparable significance, and that fundamentally is what my critique is about. Whatever one thinks of individual New Yorker cartoonists, whatever one finds funny, and whatever level of credence one puts in Sturgeon’s law, my problem with the magazine is basically that it has never nurtured the same level of ambition for its cartoons than it has had for its other content. Ross’ vision has been an increasingly deadening factor that no-one’s really cared to challenge, it seems to me.

I definitely agree with this assessment of the New Yorker’s cartoons, but I have to quibble with one little aside here about the magazine itself. In contrast to, say, the New York Times, the New Yorker acquitted itself admirably during the lead-up to and invasion of Iraq, probably most notably by publishing Seymour Hersh’s exposes about the abuses of prisoners at Abu Ghraib (and a good deal of other excellent reporting by Hersh about the rush to war).

That’s not my memory of it. I remember reading it, and the New York Times, in the run-up to the war and feeling frustrated that neither wanted to come out and state what was obvious: that Colin Powell lied at the UN and that the rationale for war was almost entirely bogus. Or at least suggest it. The editorial position was instead timidly supportive. As for Hersh, I can’t remember his articles that well, I may not have read them (except the Abu Ghraib one, and that came later, obviously), but I’m sure you’re right. In any case his contribution was more than outweighed by Jeffrey Goldberg’s biased and manipulative reporting, of which there was a lot.

The lack of genuine political/social content during the classic era of New Yorker cartoons is indeed problematic, though there were a few exceptions. Dana Fradon (ex-husband of Ramona!) did a few rather pointed cartoons such as one showing a group of “natives” worshiping a figure of Uncle Sam while an “explorer” type who is observing this notes that the CIA has been especially active in this area. Given that the “native” and “explorer” were standard tropes of magazine cartooning of the era, this can be seen as at least mildly subversive. That cartoon doesn’t seem to be available through the cartoon bank, but some of Fradon’s other stuff is: http://www.condenaststore.com/-sp/Corporate-Leaders-Gather-In-A-Field-Outside-Darien-Connecticut-Where-One-New-Yorker-Cartoon-Prints_i8476957_.htm

“The difference between Mad and the New Yorker is that the former has always been crassy commercial, while the latter has always been a refined and genteel part of the New York intelligentsia.”

I think I get what you mean here, (that Mad is pitched to a wider audience), but it’s worth mentioning that Mad didn’t accept advertising until really recently, where the New Yorker has been sick w/perfume and scotch ads for as long as I can remember.

Good point Nate. I looked through some New Yorkers from the sixties/early seventies recently at a used book store and I was amazed to see how many ads there were, including pages where the “content” was just one narrow column in the middle of the page. I don’t think they do that too often any more.

Matthias,

This is a great piece, though I disagree with nearly everything in it!

I tend to think of the cartoons in The New Yorker as an intentional counterpoint to the magazine’s serious writing, and even its spot illustrations, which are more openly ambitious than the cartoons are — they may be my favorite part. The cartoons are fairly light: a lot of jokes about stuffy alienated urban intellectual types and technology. Not my real preference, but most are fine and many are really good and some are great. If I had my own magazine, I would hire Kaz, Lisa Hanawalt, Matt Furie, Johnny Ryan, Tom Gauld, Jen Sorensen, and Abner Dean.

Most of my disagreement comes down to issues of taste and expectations; mine are the opposite of yours, in this case. I see what you are saying about a lack of aesthetic adventurousness and political content, but that’s not what the NY goes for in its cartoons; I don’t read it expecting that, though if you do or if that’s what you want in cartooning, it makes sense you would be disappointed. It’s a reasonable response, I just don’t share it.

I think the magazine shows a real stylistic diversity in the cartoonists it uses, which I like, even if none of them are all that innovative or challenging. I even think the caption contest is great; I’m repeatedly surprised by how clever the submissions are. And I don’t think the contest has much to say about the magazine’s shtick, though. Its presence is justified by its funny-ness.

“Another icon is Charles Addams, possessed of a genuine yen for the absurd yet ultimately toiling it in service of warm reassurance.”

If there’s one thing I don’t see in Addams, it’s “warm reassurance” . . . I can see how that term might apply to many of the magazine’s current cartoonists, but not him.

“Worst is the utter lack of visual ambition — one plump Addams character pretty much substitutes for another, any signs of individuality listlessly muddied up in drab wash.”

They don’t look alike to me, and if he lacks visual ambition, that’s ok with me too, as I love his style, as un-ambitious as it may be . . .

Anyways, a very smart essay!

I agree with Ken P. about Addams, I simply don’t see “warm reassurance” in most of his best stuff.

Another of my favorite New Yorker cartoonists not mentioned here is Geo. Price. Not only was he a spectacular draftsmen, but his portrayals of families (often depicted as quite poor) were anything but sentimental or lovable.

Thanks for commenting Ken and Daniel!

I sort of agree with your argument about the cartoons providing counterpoint, Ken, and actually considered mentioning it my essay, but ultimately what use is counterpoint when it contrast serious journalism with lame mother-in-law jokes? To me it remains the most obnoxious conceit of the magazine.

I also get your defense of Addams — he does have a delightful, dark sense of the absurd, but it rarely if ever gets *really dangerous or disturbing. To me, there’s just something annoyingly cuddly about his plump characters and I think having Hollywood horror tropes take over most of his work with the Addams family ultimately limited the relevance of his cartoons. The Addams family and their ilk presents us with a comforting, well-known and frame of reference almost totally removed from reality. I mean, Hollywood monsters — they were clichés from the outset.

It’s true that the Addams Family members are clearly distinguishable from each other — they’re classic stereotypes, after all — but Addams’ everyman characters are cookie cutter types: round heads, pointy noses, non-plussed expressions. Take his famous cartoon of Uncle Fester at the movies, everyone else is pretty much a variation on the same vapid character.

Oh, and I hasten to repeat: I’m not looking for political content in the strips, merely *some reflection of awareness that there’s a real world happening beyond the pages of the magazine. Something I forgot to mention is that the current crop of cartoonists at the New Yorker are actually often inserting more overt political content than ever before and seem to be encouraged to do so — the problem with that is that they’re generally irredeemably lame compared to most real editorial cartoonists.

Daniel, I considered including Price in my run-through of major cartoonists at the magazine, but decided not to for reasons of attempted, but clearly failed, brevity. To me, Price was a virtuoso who gradually slackened his line, which in some ways helped his cartooning even if it made his drawings less attractive-looking.

I find him too slick and impersonal — you can tell he was trained in advertising. It is true that his character types are a cut above most of the rest, but he is hampered by the generally mediocre writing of his gag providers.

Anyway, thanks for the responses. I would love to hear more about why I’m wrong!

It’s interesting that this post has generated only a moderate number of comments — nothing like the V for Vendetta of Maus posts, for example. I guess the point is fairly obvious, but…people just don’t care about New Yorker cartoons that much. They’re fairly highly critically ranked when people rank such things, but there’s obviously not the visceral level of enthusiasm that there is for (say) the old EC comics.

I think you’re right to an extent — there’s not so much to get passionate about there, I suppose.

But, and I’m less sure of this, the readers of HU seem to skew more toward a comics-reading audience for whom panel cartoons (historically as well as currently) are not really on the radar, and less toward the kind of (probably older) media consumer for whom such cartoons either were or continue to be a factor. I know that for me, a semi-regular reader of The New Yorker, the extent to which they factor into my interest in the magazine at all it is as an annoyance.

Definitely true that HU focuses more comics than cartoons. It’s possible that that’s just idiosyncratic to the site…but my sense is that it’s true more broadly as well? Maybe that’s wrong though.

Okay, before I get to the heart of the matter, my personal statement of eternal love for New Yorker cartoons, let me give you my New Yorker cartoon-reading history: I’m 46 years old and I grew up reading New Yorker cartoons in the collections, which were a big part of my childhood. As with my longstanding love of Walt Kelly’s POGO, this love of New Yorker cartoons is actually very much a family thing, since both of my parents and my paternal grandparents were fans of New Yorker cartoons as well. As with so many others, I read New Yorker cartoons (in the collections, but also in doctors and dentists offices) long before I actually started reading the magazine regularly, though I eventually became (and remain) a fan of the magazine and began reading it regularly about 22 years ago. I can even remember the article that pushed me into thinking that it was a magazine worth reading regularly: a long profile of Merle Haggard that ran in the spring of 1990.

It’s worth mentioning that I became a resident of New York city itself about 2 years ago. This is important but I’ll explain why later.

I’ll also reiterate the point made by several others that as always, Sturgeon’s Law applies, particularly with regard to the 2004 Complete Cartoons of The New Yorker collection. In addition to the “trying to take a sip from a firehose” quality of a comprehensive collection, that particular book has always bugged me since it seemed like a rush job, with a number of classic cartoons being badly printed or scanned from inferior sources and featuring generally unattractive layouts and design. My preferred overview of what I think of as the classic years is The New Yorker Album of Drawings 1925-1975 which is easier to handle and represents a curated collection rather than a complete reprinting.

As I’ve been reading this thread and mulling over what it is I particularly love about New Yorker cartoons, the thing that I keep going back to is that these cartoons had a very active role in defining my mental image of New York itself. Like most people who didn’t grow up there (and perhaps those who did as well), my mental impression of the city has been formed by the media: King Kong, Barney Miller, John Dos Passos, Spider-Man and countless other movies, books, comics and television shows have contributed to the New York of my mind, but I think that in many ways, New Yorker cartoons probably formed the strongest impression. In New Yorker cartoons I saw Grand Central Station (which I now see regularly) or the now-vanished old Penn Station (which I never saw in real life), its museums, apartment buildings, skyscrapers, subway stops and even its suburbs long before I experienced them in reality. A few examples:

Richard Decker: http://imgc.allpostersimages.com/images/P-473-488-90/61/6147/LY2G100Z/posters/richard-decker-i-can-t-help-that-these-invoices-have-to-be-in-the-mail-tonight-new-yorker-cartoon.jpg

Not only is this a genuinely funny cartoon and an excellent drawing but it also has a certain sadness about it. Many of my favorite New Yorker cartoons seem to feature individuals dwarfed by the sheer scale of the city.

Another favorite example (which I can’t seem to find a decent scan of) is by Alan Dunn from the sixties, showing a tiny car arriving at a giant high rise apartment with the caption “It’s good to get home again.” Shades of J.G. Ballard!

Another one, by Bernard Tobey depicting an all-too common feeling among city residents: http://imgc.allpostersimages.com/images/P-473-488-90/61/6150/XRCG100Z/posters/barney-tobey-this-neighborhood-sure-has-changed-since-i-was-a-kid-new-yorker-cartoon.jpg

There are many other examples of this type of cartoon and while I realize that this only represents one type of New Yorker cartoon, these are often the ones that made the biggest impression on me when I first read them and they’re still the ones I love best. And since I’ve moved to the city, I often see elements of those strips in my own experience of it: feeling dwarfed by the immensity of it all, but still finding small moments of beauty and humor in it.

Of course there are other types of New Yorker cartoons and cartoonists and I love them as well for the reasons I’ve already outlined. (Another overlooked favorite from the earlier days would be Mary Petty who, like Helen Hokinson, generally depicted the foolishness of the upper classes)

And just to get to some specific comments you made, I would argue that the things you don’t like about Chas Addams can be as much strengths as weaknesses. The humor of the “Uncle Fester at the movies” cartoon that you mentioned actually benefits (IMO) from the fact that the figures are generic with Uncle Fester’s happy grin contrasted with the look of horror on the faces of the other audience members. It wouldn’t be as funny with Morticia or Gomez, despite the fact that the running gag of the entire Addams Family series is essentially a variation on the “Bizarro World” concept: what we think of as awful, they love. (As an aside, it’s a pity that the Addams Family, which constitutes a fairly small part of Addams’ body of work, has overshadowed the rest of it in the mind of the public.)

My only real issue with the overall history of New Yorker cartooning is that they perhaps overemphasized their regulars over their more occasional contributors. I’d put John Glashan right up there with Geo. Price or Chas Addams as a gag cartoonist and as an artist, but they never ran all that many of his cartoons. In his case it might be regional prejudice, though his depictions of London often seemed to have that same quality of tiny individuals dwarfed by architecture that I see in New Yorker cartoons.

In conclusion Matthias, I am never going to change your mind. But I hope I can at least give you some insight into why someone else might find much to cherish in these cartoons.

Perhaps in another post I can talk about more recent developments. Surely we can all agree that the appearance of Emily Flake’s cartoons in recent years indicates that the worlds of New Yorker cartooning and “indie” cartooning are not so distant?

Sorry, this out of topic, but what happened to Penn Station?

I was referring to this, which all happened before I was born:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pennsylvania_Station_(New_York_City)#Demolition_of_station_building.3B_construction_of_Madison_Square_Garden

The old station appears in older New Yorker cartoons and its demolition is noted in later cartoons, including this one by Roz Chast: http://imgc.allpostersimages.com/images/P-473-488-90/60/6005/AXFB100Z/posters/roz-chast-how-the-old-penn-station-got-demolished-new-yorker-cartoon.jpg

And just to bring things back to my comments, here’s one by Alan Dunn: http://imgc.allpostersimages.com/images/P-473-488-90/61/6149/QBCG100Z/posters/alan-dunn-where-do-you-want-penn-station-new-yorker-cartoon.jpg

Another New Yorker cartoonist who really captures the idea of the individual dwarfed by the city is Jean-Jacques Sempé, though usually on the cover rather than the interior. Do a Google image search on his name to see many examples (including a few of Paris. Oops! Does this strengthen or weaken my case?)

Ok, thanks! Dunn was a great cartoonist who used the medium to criticize architecture.

And Sempé can only strenghten any case.

Compare and contrast.

Jean-Jacques Sempé: http://www.artvalue.com/image.aspx?PHOTO_ID=2315174

John Glashan: http://boogalaxy.blogspot.com/2008/02/anode-enzyme-iq-12790.html

Okay, now I’m the one getting off topic here. But one point I want to add is that New Yorker cartoons really should be discussed in the context of “gag cartooning” in general in the US and the rest of the world. The New Yorker is simply the last output of a once-vibrant scene.

One more. This is in the “upper class twit” mode of New Yorker cartoons rather than the “individuals dwarfed by the city”-type thing that I was talking about above, but it’s a wonderful cartoon, filled with lots of little details that you can get lost in: http://www.fulltable.com/vts/n/y/rose/SH328.jpg

Seriously, what’s not to love here?

———————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

It’s interesting that this post has generated only a moderate number of comments — nothing like the V for Vendetta of Maus posts, for example. I guess the point is fairly obvious, but…people just don’t care about New Yorker cartoons that much. They’re fairly highly critically ranked when people rank such things, but there’s obviously not the visceral level of enthusiasm that there is for (say) the old EC comics.

———————-

(Cocks gun; looks down at the fishies swimming about their cylindrical wooden enclosure; aims…)

First, “V for Vendetta” and “Maus” are individual works, easier to appreciate, assess — or attack — than a widely-varied body of work over a span of decades, by dozens (hundreds?) of individual creators.

Next, the overall accusation against the “New Yorker” cartoonists was simply “mediocrity,” rather than the far more inflammatory case made against V for V: “brazenly misogynist, horrifically violent” earning it (I believe) the greatest number of responses…

…or the utterly idiotic (but response-stimulating) “I hate Maus. Let me count the reasons why. I’m not allowed to hate it, for one thing; I always find that annoying…”

Further, the “New Yorker” is (brace yourselves!!) aimed at an entirely different audience than that which hangs out at HU, or the TCJ message board, where a similar anti-New Yorker-cartoon attitude prevailed.

Does this dearth of response = “people just don’t care about New Yorker cartoons that much”? Why, I’d bet a “New York Philharmonic — A Legacy of Mediocrity” piece would’ve elicited a similarly ho-hum reaction here.

There are actual, “reality-based” reasons why one could find current “New Yorker” cartoons a come-down from the Good Ol’ Days. The size of reproduction has, on average, drastically diminished; visual panache and rendering skill are no longer to be expected (that Mankoff’s drawings are abysmal likely leading him to the “it’s the idea that’s more important” mind-set); the humor is far more insular, catering to a narrower audience (a cartoon a few months back took for granted the reader would know who Calatrava was, while in the Olden Days, we’d get stuff the man in the street would laugh at, featuring prizefighters, chorus girls, clueless society dowagers.

Instead, we get griping about how they’re “sexist.” Helen Hokison’s 1937 cartoon featured below this charge; featuring…a woman who likes to go shopping! The outrage! (I guess we can be glad that “misogyny” wasn’t tossed in…)

…and their “aloofness from the common struggle”; that “The New Yorker’s cartoonists almost never managed to comment intelligently — or indeed at all — on the important events of their time, be it the Great Depression or the Second World War, the civil rights movement or Vietnam.” Oh, so they should have featured political cartoons? Yet, in another HU thread it was argued that those were likewise inherently doomed to mediocrity.

Addams is put down for his “utter lack of visual ambition.” Never mind that for the illustrative function of cartoon rendering, experiments into, say, Cubism or Impressionism would get in the way of the gag; be too visually intrusive.

To the overall tone of the magazine (to which I remain a devoted, and delighted, subscriber), an angry, “edgy” subject-matter and approach (á la George Grosz) would’ve likewise been disruptive.

Still, though, this is by far the most intelligent of the “Hate Fest” offerings I’ve read (which regrettably ain’t saying much), Wivel particularly astute when parceling out praise…

Mike:

‘Addams is put down for his “utter lack of visual ambition.” Never mind that for the illustrative function of cartoon rendering, experiments into, say, Cubism or Impressionism would get in the way of the gag; be too visually intrusive.’

What about Saul Steinberg?

If you haven’t seen the “Nicholas” books Sempé did with René Goscinny (of Asterix fame), you should…They’re pretty hilarious…and Sempé’s illustrations are great.

Steinberg’s an interesting case, but I think he may have been a one-of-a-kind.

William Steig is worth mentioning again as a New Yorker cartoonist willing to experiment. Matthias points out that Steig’s style evolved, but as I understand it, his change was actually quite abrupt and that he essentially changed his whole approach to cartooning mid-stream and stopped doing pencil roughs which were then inked in favor of working directly in ink, for a more spontaneous feel.

“Surely we can all agree that the appearance of Emily Flake’s cartoons in recent years indicates that the worlds of New Yorker cartooning and “indie” cartooning are not so distant?”

Yes, unfortunately. The introduction of indie cartoonists over the years has coincided with a dropoff in rigor. Rather than a finely honed idea being the goal the current status quo is a complacent “it’s all good” illustration-first vibe.

Wow, lots of great comments, and lots for me to address I guess. Thanks Daniel, for that fine defense of the cartoons — I agree that the Decker cartoon is good, really atmospheric, and I also agree than Dunn had his moments (The Penn station cartoon is wonderfully pithy). And Sempé is of course great, but as you say he kind of falls outside the scope here, since he didn’t do any gag cartoons for the magazine.

Carl Rose is also often good — his cartooning is a bit dull, but often works well in service of very strong ideas. The one you reproduce is a fine satire of the 1%, and one might imagine an effective contemporary update of it.

That being said, I’m not overly impressed by mockery of the upper classes by such cartoonists as Hokinson or Petty — yes, they are often quite witty, but there’s something snobbish about them, made as they are in appeal to an upwardly mobile middle class. It’s insular.

Again, since it doesn’t seem to have been made sufficiently clear, I want to repeat that I’m not looking for political cartooning. I know that was never the point, but as I wrote even social criticism can show intelligent engagement in relevant issues of their day, just as the Rose cartoon I reproduced does. This is what I’m talking about, though it’s not something I would demand of *every cartoon.

As for the cartoons as a visual-verbal record of New York life, I suppose that comes down to what one’s experience of the city is like. To me, the magazine has mostly offered either romanticized (e.g. the Reuben sandwich being hoist up to a high rise construction worker) or snobbish (see above) renditions, none of which ring true to my experience of living there, but I’m just one, one-time New Yorker out of millions…

Re: Addams, I made the point about genericness using that famous cartoon, but I think it applies much more generally. Also, although Addams did much non-“Family” work, but much of it works within the same comfortable fantasy framework, eliciting humor from SF/horror/etc. tropes with very little relation to life as lived.

Oh, and I agree that The Complete Cartoons is a deeply flawed publication, with lots of inferior reproduction and a generally uninspired selection of cartoons on the printed pages of the book itself.

——————

AB says:

Mike:

‘Addams is put down for his “utter lack of visual ambition.” Never mind that for the illustrative function of cartoon rendering, experiments into, say, Cubism or Impressionism would get in the way of the gag; be too visually intrusive.’

What about Saul Steinberg?

——————–

Touché!

Though Steinberg is an exceedingly special case; a unique genius…

Ah! reading on (as usual, I started answering without reading what came after) I see someone anticipated that remark:

——————–

Daniel C. Parmenter says:

Steinberg’s an interesting case, but I think he may have been a one-of-a-kind.

———————

———————

Matthias Wivel says:

…I want to repeat that I’m not looking for political cartooning. I know that was never the point, but as I wrote even social criticism can show intelligent engagement in relevant issues of their day,

———————–

Fair enough! Certainly there’s much that’s cartooning “comfort food” therein.

It should also be mentioned that (bizarrely for a magazine that regularly features “conspicuous consumption” advertising) “The New Yorker” has printed some of the most powerful, well-substantiated attacks on the American Right of any mainstream U.S. publication; only “Rolling Stone” comes close. So, there’s more than mere “catering to the comfortable” in this truly great magazine.

Though, there is one “New Yorker” cartoonist — I canna remember his name — who’s made “class war” cartoons his field; featuring predatory-looking CEOs and execs…

(…Can we at least agree that the poetry that litters its pages is horrendous?)

————————

…although Addams did much non-”Family” work, but much of it works within the same comfortable fantasy framework, eliciting humor from SF/horror/etc. tropes with very little relation to life as lived.

————————

What, he should have done “ashcan realist” cartoons? And, certain creators have an affinity for certain types of material. Do you think Richard Sala would be as inspired with Adrian Tomine’s fave subject of dyspeptic 20-something whiners, and vice versa?

————————–

Re: Addams, I made the point about genericness using that famous cartoon, but I think it applies much more generally.

————————–

Maybe as a long-time commercial artist I “get” the realities of workaday cartooning and such a bit better; to me, it’s ridiculously obvious that the very “genericness,” the subdued visual approach of Addams, the mundaneness of settings, serves to highlight by contrast the outré events therein:

http://www.trappedbymonsters.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/charlesaddamscreeps-2.jpg

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_bBDFciBWIFU/Sdg2tf8yF6I/AAAAAAAACYc/ErSSaO-oIBU/s400/medium_Telephone.jpg

http://theinvisibleagent.files.wordpress.com/2010/02/charles_addams_cartoon_dscn6917-451×620.jpg?w=460

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-OsfMpiBGvkE/T9S-XPxt2TI/AAAAAAAABKE/XgyJAHkTcVk/s1600/Charles+Addams+%281940s%3F%29.jpg

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-z0FCRssLLCc/TwkKXNFFwmI/AAAAAAAACIs/Gs6WlO5Gc-4/s1600/charlesaddams1.jpeg

…In this he demonstrates a similar approach to one of the greatest Surrealists, Magritte. Some of whose work is almost “gag”-like. Consider:

http://blogs.artinfo.com/lacmonfire/files/2012/06/rene-magritte-castle-in-the-pyrenees.jpg

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/__c9qWlUD8Qs/TNMeyCVG8jI/AAAAAAAAM1U/3ufXKe49dvg/s1600/magritte48.JPG

http://files.myopera.com/xanna-lilly/albums/8296512/N%20-%20Rene%20Magritte,%20Call%20of%20the%20Peakseaks.jpg

http://blogs.artinfo.com/secrethistoryofart/files/2011/01/magritte_the_key_to_the_fields_1936-.jpg

http://ep.yimg.com/ca/I/artbook_2075_347149906

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-HkK70rQ9mIo/T8GvgmMdlCI/AAAAAAAAAWE/hBrhOBkuqHQ/s1600/magritte49.jpg

Some quite Addams-ish:

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_0HBA442vft0/SVpCjSPKOdI/AAAAAAAAFoc/QHGTio6w_jE/s400/Ren%C3%A9+Magritte.+The+Month+of+the+Grape+Harvest.+1959.jpg

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/7/7c/The_Portrait.jpg

http://www.mattesonart.com/Data/Sites/1/magritte/reproduction%20prohibited%201937.jpg

There are also correlations:

Magritte: http://blistar.net/images/photos/medium/4027ed7a359e9373e0bba47f586a4fdd.jpg

Addams: http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_UKr9URsCkeE/S5KZuY8IZzI/AAAAAAAAHQ4/LLPxCQqU4ng/s400/12051.jpg

Magritte: http://www.oilpaintingsreplica.com/upimages/Rene%20Magritte%20Paintings/Horse-Riding.JPG

Addams: http://static.neatorama.com/images/uploads/2007/07/charles-addams-skier-of-insanity.jpg

Magritte: http://nursemyra.files.wordpress.com/2009/02/magritte_recamier.jpg

(A take-off on this, by David: http://www.studiolum.com/wang/indrikov/david-madame-recamier.jpg )

Addams: http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_zBbk7VOCdHI/RZLk-5klvrI/AAAAAAAAAC0/mo7Ru0lFNzo/s1600-h/addams.butcher.shop.jpg

(Of course, inspired by http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-vlQ2w4AiCPw/TZbqjQBXDMI/AAAAAAAAC4c/UpPtfEY0s3Y/s1600/mythology30.jpg )

And: http://bronxbanter.arneson.name/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/ChasAddams1.jpg

(Why, yes, I madly love both Addams and Magritte. And no, I’m not holding Addams up to Magritte’s level, though first encountering his work was like a bolt of delight flashing through my soul. )

Neil Gaiman on Addams: http://journal.neilgaiman.com/2005/10/addams-thing.html

(Now Noah, compare Alan Moore on superheroes and me, debating on HU threads; who is the true “obsessive”?)

Far be it from me to suggest that you are anything but obsessive, Mike….

and sorry your comment got caught in the filter for a second there. I think it must be all those links….

Thanks for your thoughts Matthias, and everyone else as well. I’m really enjoying this thread a lot.

Re: Sempé, I’m pretty sure he did at least a handful of interior cartoons. Also I would argue that at least some of the covers, particularly during the classic era, were often essentially large captionless “New Yorker cartoons” and should be considered at least partly relevant to this discussion.

Re: Hokinson and Petty, it’s true that there’s a snob factor about Petty (and occasional overt racism, unfortunately), though I love her drawing style. But Hokinson’s whole shtick, once she started working with staffers such as James Reid Parker, seemed to be to be about deflating the pretensions (social, intellectual, artistic) of upper-class women of a certain age and shape. Certainly they’re intended as lovable, but one is laughing at them, not with them I think. (As an aside, one of the first things I noticed about the BBC television series “Keeping Up Appearances” was that its social-climber protagonist Hyacinth (portrayed masterfully by Patricia Routledge) was essentially a Helen Hokinson type. Her matronly bearing, her “candlelight suppers” and the recurring bit about answering the phone with “The Bucket residence, the lady of the house speaking” seemed right out of Helen Hokinson’s world to me.)

Re: The absence of social criticism, I can certainly see your point and the fact that the classic era was indeed squarely aimed at the upwardly mobile class is particularly problematic when it comes to someone like Charles Saxon. I genuinely love his drawings, but there’s a particular series by him depicting vapid small talk at a garden party where all of the captions could easily be replaced by “You do realize that we’ll all be first against the wall when the revolution comes, don’t you?”

Re: Chas Addams, I think we’re just going to have to agree to disagree. I love his stuff unreservedly. He was one of the first New Yorker cartoonists that I really glommed onto in fact and for me, those aspects that you identify as weaknesses in his work are things that I see as strengths. I love his miniature people, his gorilla who “might be making a citizen’s arrest”, his department store Santa Claus who takes off his fat suit and dons street clothes before climbing into his flying sleigh etc. It’s true that Addams’s work seems utterly disengaged from life as it’s really lived, but I guess I’m not looking for that in his stuff and so I’m not disappointed by its absence. One of his collections is even rather aptly titled “Creature Comforts”.

Thanks Mike, especially for the Magritte comparison! Not a connection I’d have made, though I can see your point about some of them having a certain Addams-ish quality to them.

My pleasure!

———————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

Far be it from me to suggest that you are anything but obsessive, Mike….

————————

Yes: http://laughingsquid.com/someone-is-wrong-on-the-internet/

————————

and sorry your comment got caught in the filter for a second there. I think it must be all those links….

————————-

No problem, I’ve seen it happen before!

—————————-

Daniel C. Parmenter says:

…Hokinson’s whole shtick…seemed to be to be about deflating the pretensions (social, intellectual, artistic) of upper-class women of a certain age and shape. Certainly they’re intended as lovable, but one is laughing at them, not with them I think.

—————————–

Hm! Which reminds of a certain one-panel cartoon series (called something like “The Girls” or “The Ladies,” but neither of those) which, I dimly recall, ran in a magazine (“Saturday Evening Post”?) and specialized on that group of clueless dowagers.

In one, a batch of these grande dames are laying about, catching the sun in a Western-themed spa, attendants ferrying drinks to them. One says to another, “You have to live like this to appreciate the courage of the pioneers who first settled the Old West!”

Sounds like Helen Hokison fare, but it’s not mentioned here. Hokison’s life and dramatic death at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helen_E._Hokinson .

That “New Yorker” cartoonist with the “class war” specialty is Charles Barsotti:

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_GRSId-tHKhk/TQaCR13dpJI/AAAAAAAAAEw/CwPZopD_nJ8/s1600/barsotti.PNG

http://imgc.allpostersimages.com/images/P-473-488-90/60/6006/FWGB100Z/posters/charles-barsotti-move-to-sweden-new-yorker-cartoon.jpg

http://hecatedemeter.files.wordpress.com/2011/12/charles-barsotti-no-i-didn-t-i-never-said-there-should-be-no-government-regulation-new-yorker-cartoon.jpg?w=473

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_6zFiwogUkPk/TJbSQPnMD-I/AAAAAAAACao/2JEcRZMWpB4/s1600/New+Yorker+Cartoon+-+we+can%27t+all+work+at+GS+%28by+Charles+Barsotti,+10-26-2009%29.png

(Can’t…stop…linking ! I’m “obsessing” again…)

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-3B8_ZhyyRh8/TxZWuhi2jSI/AAAAAAAACOg/VusSxf1ws48/s1600/charles-barsotti-i-got-it-this-far-don-t-stop-me-now–new-yorker-cartoon.jpg

http://ronbyrnes.files.wordpress.com/2012/05/charles-barsotti-hey-everybody-quigley-is-practicing-his-perp-walk-new-yorker-cartoon.jpeg?w=584

————————–

Daniel C. Parmenter says:

…It’s true that Addams’s work seems utterly disengaged from life as it’s really lived, but I guess I’m not looking for that in his stuff and so I’m not disappointed by its absence. One of his collections is even rather aptly titled “Creature Comforts”.

————————

On the theme of “creature discomforts,” Addams put together “Dear Dead Days,” which — though featuring his lovably ghoulish cartoon family on the dustjacket — is a collection of creepy real-life, old-time stuff; along the theme of that “The Good Old Days – They Were Terrible!” book. I distinctly recall one photo of a corpse frozen in a block of ice; a system for “electroplating a baby”: http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2918889-dear-dead-days

See, also:

http://www.addamsfamily.com/addams/ddtitle.jpg

http://addamses.blogspot.com/2009/04/dear-dead-days.html

Hmmm, some photos from that book here:

http://bencatmull.blogspot.com/2009/04/dear-dead-days.html

Interesting stuff, though the book seems to be a bit of a bait-and-switch. Addams Family on the cover, pre-Internet compendium of weirdness on the inside. Presumably this was due to the fact that there weren’t really all that many actual Addams Family cartoons.

A good opportunity to mention again that the “A-Fam” cartoons are (IMO) not necessarily Addams’ best stuff. I suppose they’ve been good for the estate, what with the TV show (which I never liked), movies, etc. but I still prefer his miniature humans, apes, etc.

Just got my latest “New Yorker” in the mail: http://media.photobucket.com/image/new%20yorker%20october%206/Greg94501/October/Cover-6.jpg

Heh, that butchershop Laocoon is kind of funny, I’ll give you that Mike. Look, it’s not that I find Addams totally without merit or anything, but to me he is very much surrealism lite and cutesified. For example, what does that gag with the kid and the monster on the stairs tell us about anything? It’s just wrings humor from a cliché, and the gag in the one with the aliens — which is among the more visually adventurous in Addams’ catalogue — is just so *lame.*

Magritte himself is pretty uneven, but does admittedly have some fantastic, unsettling ideas. I don’t see that much of a connection though.

I like the Hyacinth-Hokinson connection, Daniel!

As for Sempé, I can’t find him anywhere on the Complete Cartoons discs.

Thanks Matthias! The Hyacinth/Hokinson thing seems like a good fit, though I doubt very much that the show’s creators had Hokinson in mind. I suspect it was just a case of parallel evolution, based on the comedic possibilities of a particular “type”. KUA digs a lot deeper into class implications, particularly in regard to how Hyacinth interacts with her family. One gets the sense that Hyacinth is striving to be what Hokinson women are born into.

Re: Sempé, I could have sworn I saw a gag cartoon by him last time I was going through that 1925-1975 collection, but right now I’m on a Lucky Star bus on my way from NY to Boston so I can’t check! But I suppose the Complete Cartoons disc is the final word on the matter.

————————-

Matthias Wivel says:

…it’s not that I find Addams totally without merit or anything, but to me he is very much surrealism lite and cutesified.

————————-

Yes; and your point is…?

Must I dig out and post yet again that true story about the guy who loudly griped the “Oklahoma!” wasn’t “Macbeth,” and vice versa?

So you want Addams to be truly, not tamely, creepy and unsettling, deeply psychologically disturbing?

Like Munch, Ensor, or the splendid Alfred Kubin?

http://themorbidimagination.com/art/alfred-kubin/

http://beautiful-grotesque.posterous.com/the-art-of-alfred-kubin

Uh, did it ever occur to you that for a gag cartoonist, this might be a trifle…self-defeating?

A work should be assessed not only for its own merits, but for what it’s trying to do, and how successfully it meets the desired goals.

The work may not have particularly elevated goals, but it’s absurd and unjust to attack a nicely-cooked hamburger for not being adventurous, taste-challengingly innovative cuisine; to bash Ian Fleming for not being John LeCarré, Agatha Christie for not being P.D. James.

Which, in reverse, is my latest literary consumption: gone from rereading James’ “The Skull Beneath the Skin” to rereading Christie’s “The Body in the Library.” Certainly, Christie’s people are cardboard — even if brightly-colored cardboard — compared to James’, the settings barely sketched out; there is no real sense of dread or horror.

Yet Christie (though this is hardly one of her finer efforts) has her own compensating qualities. For instance, Hercule Poirot is so splendidly wrought a character, in his charm, eccentricities, peculiarities and vanity, that he quite outshines James’ complex, three-dimensional characters, with all their shades of Grey.

Moreover, if the writerly virtues P.D. James — or John LeCarré — have were to be injected into Christie’s or Fleming’s books, the works of the latter authors would not gain, but suffer; be thrown out of whack by all the complexity and seriousness.

————————–

For example, what does that gag with the kid and the monster on the stairs tell us about anything?

————————–

How…insubstantial can you get? Why, it utterly fails to deal with The Meaning of Life, or Man’s Place in the Universe!

(Can one fling rotten tomatoes at critics?)

————————-

Magritte himself is pretty uneven, but does admittedly have some fantastic, unsettling ideas. I don’t see that much of a connection though.

————————-

Well, they’re there, and couldn’t be more blatant. That “reclining coffin” canvas, for instance, is pure Addams. (The very fact that it’s so beautifully painted, in color, and detailed, oddly detracts from its being effective as a cartoon.)

Elsewhere, Magritte is brilliant, subtle, thought-provoking, poetic. Why, this is not only eerily surreal, but moving, melancholy: http://www.artwallpapers.org/paintings/ReneMagrittePaintings/images/Rene%20Magritte%20Painting%20023.jpg .

But, as a gag cartoonist; sorry, Magritte! Just not funny enough…

(Am reminded of a “National Lampoon” bit about Marc Chagall’s [invented] career as a police sketch artist: “He was unwittingly responsible for instigating several pogroms…everyone he drew looked Jewish!” See, also: http://www.cartoonstock.com/directory/p/Police_sketch_artist_gifts.asp )

Magritte has some truly discombobulating ideas, Addams just some quirky ones. They’re not in the same league. Forget about gags or not.

I’m all for judging things for what they are, and going by that I find Addams’ general strategy of wringing humor from Hollywood tropes and other clichés too insular. He doesn’t come close to his disciple Gary Larson, for instance, who generally presents a really original and surprising view on things.

I’m not talking about cartoons exposing the Meaning of Life, merely cartoons that feel relateable to life. Larson’s are, they make you see things differently, they observe little things that are very real, plus they a carried by an admirable ethos.

I like Gary Larson a lot more than I like Magritte.

And it totally makes sense to think of Magritte as a (mediocre) gag cartoonist. He’s all about the one-liner.

He is also a very bad painter. His works look much better in reproduction than in the flesh.

It shows, even in repros.

Daniel: your memory didn’t fool you. There are indeed some drawings by Sempé in the 1925-1995 book (pp. 134, 135). According to Lee Lorenz these were published as spreads published under the title “Par Avion.”

It pleases me that even Domingos and Matthias can agree on the crappiness of Magritte. He really is an iconic nadir of glib postmodernism….

Thanks for looking it up. The whole subject of non-gag illustrations, covers, “spot” illoes, random filller, title headings, etc. in the New Yorker over the years is a whole other fascinating topic. Some of the spot drawings recently have been great. The science fiction-themed issue for example featured a series of these that made up a narrative sequence about a murderous robot. A couple of weeks ago several featured a recurring tiny Superman-like figure. I think Loustal even did a series with a mini-narrative.

—————————–

Matthias Wivel says:

Magritte has some truly discombobulating ideas, Addams just some quirky ones. They’re not in the same league. Forget about gags or not.

—————————–

Indeed, “Magritte has some truly discombobulating ideas.”

But, in order to dismiss a gag cartoonist as inferior to Magritte, you say, “forget about gags”? That’s an…interesting tactic.

And as I said earlier, if a cartoonist goes too far into strangeness, it becomes a self-defeating approach. (See the Larson “Cow tools” story farther down.)

——————————

I’m all for judging things for what they are, and going by that I find Addams’ general strategy of wringing humor from Hollywood tropes and other clichés too insular.

——————————

Sorry; there are a great many Addams cartoons that fail to fall within those narrow parameters.

——————————

He doesn’t come close to his disciple Gary Larson, for instance, who generally presents a really original and surprising view on things.

——————————

Yes, Larson’s work is — if not as visually tasty — indeed more imaginative and inventive.

(Not quite as much as Kliban; though in bizarrerie such as “Cow tools” Larson could come close: http://ericdurso.com/2010/02/16/cow-tools-why-is-gary-larson-so-funny/ .)

——————————-

I’m not talking about cartoons exposing the Meaning of Life, merely cartoons that feel relateable to life.

——————————-

I agree with Hitchcock; rather than art which is a “slice of life” — or bears too much resemblance to that noxious, fortunately finite condition — I prefer that which is a “slice of cake.”

And the idea that Larson’s “feel more relatable to life” than Addams’ is utterly absurd. Why, weren’t you arguing in the previous line (how soon they forget!) that “Larson…generally presents a really original and surprising view on things”?

Alas, in life the humdrum and predictable are the rule rather than the exception. As a commercial artist, I can testify that the “original and surprising”are routinely despised, trampled into the ground, and “mediocrified.”(Which is why I’ll have another slice of cake, please!)

——————————

Larson’s are, they make you see things differently, they observe little things that are very real, plus they a carried by an admirable ethos.

——————————-

Yup, there’s a gas station! Very real! Why, Addams never observed things that are “very real” or “relateable to life” like someone packing lunch in a kitchen; or, say, people going to the movies…

…Oops!

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_zBbk7VOCdHI/Shr_cCg40DI/AAAAAAAAClY/p8pRITGn49M/s1600-h/Addams_lunchBoxBomb.jpg

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-vIzEuf4F3rk/UEt2VgvAHiI/AAAAAAAAB4M/8rieKOGJoKQ/s1600/4+Charles+Addams.jpg

And what’s this “carried by an admirable ethos” bit, now? What’s next, shall we critique by who’s the sharpest dresser?

——————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

…it totally makes sense to think of Magritte as a (mediocre) gag cartoonist. He’s all about the one-liner.

——————————-

I was deliberately picking his “gag cartoonist”-like paintings. There is much of his work — I have books and books’ worth — which is not.

Like…

http://www.artwallpapers.org/paintings/ReneMagrittePaintings/images/Rene%20Magritte%20Painting%20023.jpg

http://www.dailyartfixx.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/The-Voice-of-The-Winds-Rene-Magritte-1928.jpg

http://www.wallcoo.net/paint/magritte/images/Magritte_Artwork_ml0002.jpg

http://www.mattesonart.com/Data/Sites/1/magritte/Memory%201942.jpg

http://www.mattesonart.com/Data/Sites/1/magritte/La%20Page%20Blanche%20%20%20%28The%20Blank%20Page%29%201967.jpg

———————————

Matthias Wivel says:

He is also a very bad painter. His works look much better in reproduction than in the flesh.

———————————

Oooh, a “very bad painter”! Forget about Magritte’s concepts, playing with perception, the emotions his workd evoke, their visual poetry.

…Because the all-important factor in painting quality is the finish, lissome textures, rich impastos and dancing brushstrokes!

(John Simon had once said, “In discussions, I often find myself out of my depth.” [Surely not!] “This time…I’m out of my shallowness.”)

As I’d written earlier, “…to me, it’s ridiculously obvious that the very ‘genericness,’ the subdued visual approach of Addams, the mundaneness of settings, serves to highlight by contrast the outré events therein…In this he demonstrates a similar approach to one of the greatest Surrealists, Magritte.” (Emphasis added)

——————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

It pleases me that even Domingos and Matthias can agree on the crappiness of Magritte. He really is an iconic nadir of glib postmodernism….

——————————–

Why am I not surprised?

Noah: I didn’t say that I don’t like Magritte. I interpreted Matthias’ “[h]e is also a very bad painter” as “he is also a very bad technician.” Which he was. Maybe not “very bad” exactly, but bad enough. Still, I largely prefer Magritte to Frank Frazetta (a hugely talented technician).

I prefer Frazetta. I really don’t like Magritte at all.

I like Magritte just fine myself, though “surrealism lite” seems about right for a lot of his stuff.

Interesting points re: Gary Larson though. Larson is pretty clearly a child of Addams and yet I agree w/Matthias that Larson seems a bit more engaged with the world at large. Hard to imagine Addams coming up with the idea of a children’s book about a family of worms called “There’s a Hair in My Dirt” and using it to touch on scientific and environmental themes.

BTW, apropos of nothing, here’s another favorite Alan Dunn cartoon, complete with beautifully-drawn architecture and a drug reference, in 1957 no less! This small version doesn’t do it justice, but here it is:

http://imgc.allpostersimages.com/images/P-473-488-90/61/6147/DX2G100Z/posters/alan-dunn-what-was-the-name-of-that-tranquilizer-we-took-new-yorker-cartoon.jpg

Mike, I think we just gotta agree to disagree here, but your post is marked by a number of misreadings and -perceptions that I can’t leave as is.

First of all “relatable to life” doesn’t mean kitchen sink realism. I’m puzzled why you think it would, and why an original or surprising take on life somehow does not constitute relating to it in your book. I mean, the word I used, “observation”, directly implies something real being observed. No?