It’s very likely that Chris Ware’s Building Stories will be the most publicized alternative comic release of 2012. Like Habibi last year, it will be one of the few comics that the larger public will hear about, and will be encouraged to read. NPR’s Glen Weldon thoughtfully reviews it, concluding that it “is beautiful.” The Telegraph announces, “his new book, if one can call it that without being reductionist, is a work of such startling genius that it is difficult to know where to begin,” and that “Ware’s latest offering has elevated the graphic novel form to new heights.” EW’s Melissa Maerz gives the book an A+. Sam Leith, an author, journalist and occasional critic for the Guardian, relates, “There’s nobody else doing anything in this medium that remotely approaches Ware for originality, plangency, complexity and exactitude. Astonishment is an entirely appropriate response.” The New Yorker, in which Ware regularly contributes and in which an excerpt of Building Stories has been published, declared its release a “momentous event in the world of comics,” contextualizing the event in a way that’s hard to put a finger on. So is a ‘momentous event in the world of comics’ news or not? Required reading?

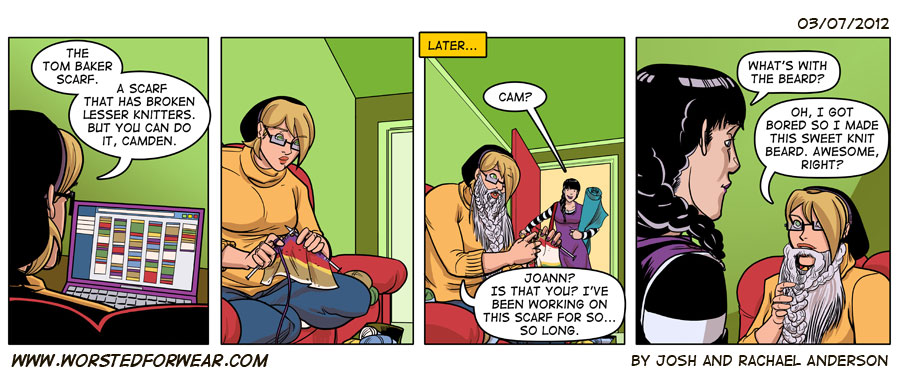

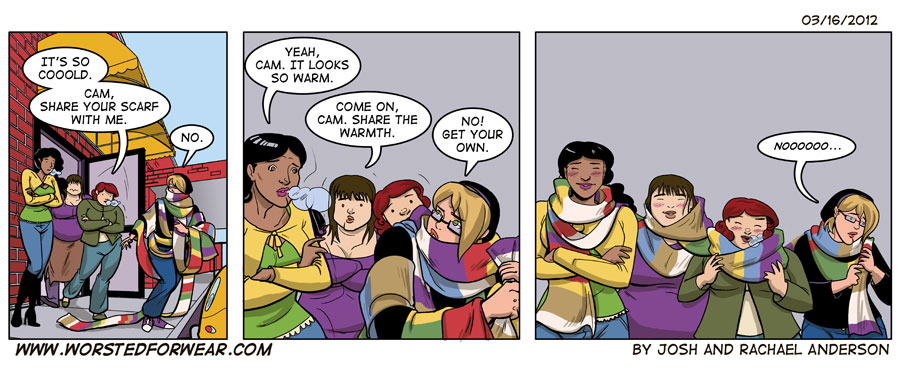

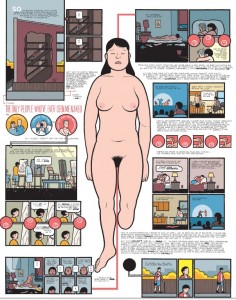

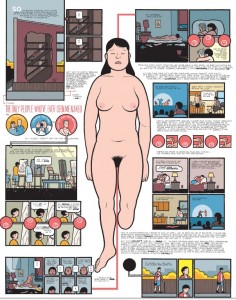

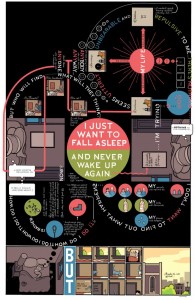

Building Stories will probably top bestseller charts for comics until Christmas, but it’ll still be a hard sell, even with reduced prejudice toward comics. Reading comics takes a lot of effort for those unaccustomed to it, and is a little ironic, considering comics’ association with instructional and children’s literature. And when a typical page looks like this:

On the other hand, the intense stylization and design of Ware’s work could make it easier to grasp what is “impressive” or “extraordinary” about it– no critical vocabulary or understanding of the comics medium is needed to “get it.” Still, picking up a Graphic Novel is an intellectual adventure for most people, and while they can be quicker reads, for an infrequent comics reader, Building Stories seems to require an intimidating amount of time and energy to absorb and reflect on.

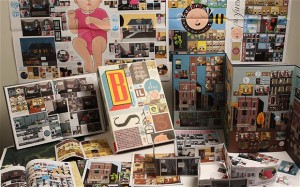

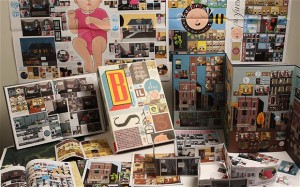

On top of that, Building Stories isn’t really a book as much as a box containing 14 intertwining narratives of varying length and form.

Photo courtesy of Julien Andrews and The Telegraph

It resists straightforward reading or easy transport. This could make the work even more daunting if it were to be consumed as a commute or a relaxing read. Except that it won’t be– Ware’s Building Stories rewards the casual reader’s belief that reading good comics is an experience worth having every now and then, but not a habit that can be integrated into one’s regular routine. Rather than challenge his audience’s preconceptions of the value of comics as something to build into one’s day-to-day, Building Stories reinforces the idea that worthwhile comics are blue moon events, and reading them is a temporary interruption in normal behavior.

In Building Stories’s defense, Ware champions the survival of print, and active reading habits. Building Stories is untranslatable to an ereader, and asserts the value of a book as an art object to be physically experienced and actively engaged. Building Stories also blurs the boundary between ‘comic books’ and the field of ‘artist’s books’ and ‘book arts’– this could be a post in itself, but still worth noting here. However, its worth wondering whether comics are already seen more as objects than vehicles for content, and whether their objecthood (and collectability) is supported by the American marketplace and culture.

Additionally, the publicity of Building Stories helps comics as a field more than it hinders it. If more exceptional works are publicized, its harder to assume that they are only exceptions in an undistinguished industry. Still, for most, reading a comic is an eccentricity, a curiosity, a ‘novelty,’ and the format of Building Stories plays into the sense of gimmickry that infrequent readers bring to reading comics. If the merit of reading comics lies in the strangeness of doing it, why not make the experience increasingly elaborate and fanciful? As the form eclipses the content, mediocre storytelling runs the risk of being excused due to unfamiliarity or low expectations of comics in the first place. Fittingly, novelty is central to Ware’s work: ragtime aesthetics, and turn of the century advertising and consumerism abound throughout Building Stories and his career. Perhaps some of his success lies in his work’s resonance with occasional reader’s nostalgic, fanciful approaches to comics, evidenced in most press coverage of releases. It’s worth noting that lifting the cover of Building Stories isn’t unlike opening a game box, or a trunk of childhood artifacts.

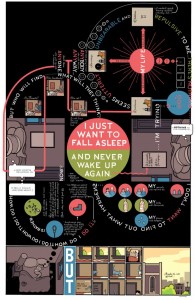

Beyond that, Ware presents a cabinet of curiosities, a wunderkammer. Its fragmented form compliments the fact that it follows several character’s perspectives, but is it overkill? Derik Badman wrote a few illuminating meditations here, including, “The narrative itself is already quite non-linear, most of the ‘chapters’ include movements through the time of memory/recall, and I think something of the protagonist’s story (and the emotional impact of it) is lost if you end up reading the later parts before the earlier parts (chronologically speaking).” On the other hand, the contributor’s to The Comic’s Journal ongoing, laudatory roundtable find the effect “sublime,” ” a kaleidoscopic vision of simultaneous human frailty and possibility”, “aspires to a graphic novel on the scale of James Joyce’s Ulysses,” and maybe most observantly, “showcases the comic medium itself by including representative examples of all its sundry forms: comic books, mini-comics, newspaper comics, chapbooks and picture books.” Building Stories evades critical readings on its overall pacing and structure: these decisions are left up to the reader, who likely chooses what to read by chance. Without skimming the pages in advance for certain visual clues, (including Ware’s recent adoption of a Clowesian and somewhat creepy drawing style,) it’s hard to predict what each booklet will hold, and many events are revisited and re-evaluated as the main character ages. There are moments of poetry, and some great easter-egg moments as one stitches sequences from different volumes together (if that’s a motivator.) Finally, a linear reading may not be the best– the later chapters of Building Stories are wearingly over-narrated, and would be a tedious way to finish the story. Building Stories as a whole is a very uneven work, and the question remains as to whether the box of stories approach enhances the material, hinders it, or if it simply cloaks the fact that, after a decade of waiting, this may not be Ware’s best work.

It’s probably unfair to say that Ware is invested in non-habituated comics reading any more so than Pantheon, crafting fetishistic, beautifully awkward and expensive book formats. But, isn’t every comics publisher following suit? Building Stories is a collector’s item by nature, and its multiple readings will probably benefit multiple re-readings– a perfect and decorative addition to a home library collection, alongside Habibi and deluxe reprints of Prince Valiant and Pogo.

On the flip-side, the format of 2012’s other heralded release, Allison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother?, is hardly experimental, but perhaps more revolutionary considering comics industry’s focus on ‘the object.’ Interestingly, Are You My Mother? embraces a lot of qualities that made comics popular in the first place. As a pretty standard book, Are You My Mother? is expected to speak for itself, and it can easily be read at one’s convenience, and in public, (which matters more to some than others.) Historically, as collection eclipsed disposability in the American market, comics’ status as an ‘object’ was magnified.

It’s possible that, despite comics’ greater acceptance as ‘literature’ than as ‘art,’ the industry is at a crossroads as to whether to pursue an ‘art object’ or ‘literature’ route. Building Stories exemplifies the former path, while Are You My Mother? follows the latter. Each route bears repurcussions for comics consumption, several of them class-based. In the United States, students are expected to graduate with some familiarity with a handful of great works, and their history, and to learn basic critical frameworks to apply to other books. Art, when not nixed from the curriculum altogether, is taught more often as a practice rather than as a history and theory. Those who learn about art are often those who can afford to, or do so at the expense of lifetimes of loans. Literature is transportable, and can fit itself into a variety of lifestyles (long bus and subway rides, for instance.) Art, focused as it is on physical, singular presences, (not duplicates,) must be approached in certain institutions, during certain hours. As a consumer, only the wealthy and initiated can participate in the collection of ‘the masters,’ while a paperback of Dostoevsky will not be less authentic than the leatherbound edition. The leather-bound is preferred when the discussion veers from literature to a subset of art collection– rare book collection. The repurcussions of Building Stories extends farther than just gimmickry, but also those of privilege. Purchased at a bookstore, Building Stories is a fifty dollar book. Will libraries, which have done so much to make comics available to the public, easily be able to loan it? And why resist digital reading? With the advent of e-readers, color comics can be as cheap to publish and as easy to find as a text book– one less hurdle in their production and accessibility. It’s worth crossing one’s fingers that, in its resentment of art-world prestige, comics will avoid enviously replicating the worst aspects of fine art. Bart Beatty’s Comics Versus Art delves much more fully into this idea– and is very much worth the read.

Perhaps making an experimental box of comics is truly an elevation of the form. Perhaps other visions of comics readership, where a handful of comics, both brilliant and bad, are sprinkled around the e-reader screens of a commuter car, is wishful, or unnecessary, (or found only in Japan.) (Apologies for the USA centrism of this piece– unfortunately, it will continue to the very end.) Comics may have a nice niche here in the States– the rare, quirky read for some of most people, and objects of obsession for few. But is there something urgent, something missing, that comics can bring to wider culture? Something that books and film and music or any other medium can’t or won’t contribute, that comics uniquely can? Something that is needed, and should be as accessible as possible? Would it matter if comics became more prevalent than they are– that comics became more accessible than inaccessible? Those outside the industry may not care one way or another– they are probably waiting for comics to answer for that.