I’ve been reading John Rieder’s excellent book Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction. There’s lots of fun discussion about nightmare invasion scenarios, lost worlds, time travel, constructed humans, and how imperialists love being imperialists, satirize being imperialists, and more or less constantly freak out about the possibility of being imperialized.

So maybe I’ll talk about all that at some point. In the meantime, though, Rieder also has some really interesting thoughts on genre. Specifically, he argues that a genre is best understood not through a strict formal definition, but rather as a group of texts that bear a “family resemblance.” The term is from Wittgenstein, and Rieder quotes a further explication by scholar Paul Kinkaid:

science fiction is not one thing. Rather, it is any number of things — a future setting, a marvelous device, an ideal society, an alien creature, a twist in time, an interstellar journey, a satirical perspective, a particular approach to the matter of story, whatever we are looking for when we look for science fiction, her more overt, here more subtle — which are braided together in an endless variety of combinations.”

Science-fiction is then a “web of resemblances.”

If sci-fi is a web of resemblances though, that has some surprising implications. Specifically, if the genre is the web, it can’t exist before the web. There can’t be a point of origin, because a point isn’t a web. For there to be family resemblances there has to be a family. Or as Rieder puts it:

The idea that a genre consists of a web of resemblances established by repetition across a large number of texts, and therefore that the emergence of science fiction involves a series of incremental effects that shake up and gradually, cumulatively, reconfigure the system of genres operating in the literary field of production, precludes the notion of science fiction’s ‘miraculous birth’ in a master text like Frankenstein or The Time Machine. A masterpiece might encapsulate an essence, if science fiction had one, and it certainly can epitomize motifs and strategies; but only intertextual repetition can accumulate into a family of resemblances.

This has some obvious implications for the much-bruted question, What Is a Comic? Like science fiction, definitions of comics (most notably Scott McCloud’s) generally focus on formal elements — a sequence of images, in McCloud’s case. As a result, McCloud includes in his definition things like hieroglyphs, while excluding single panel cartoons.

However, if comics are seen as a web of resemblances, then the effort to look for origins or predecessors or even formal tropes starts to look misguided. Instead, it’s more useful to focus on the center — on what things are accepted as comics, as I put it in a post some time back. Comics are not a formal template; they’re a genre that has taken shape since around the early twentieth century, and which can have, like science-fiction, any number of hallmarks — including (for example) sequences of images, superheroes, cartoony art, funny animals, autobiographical storylines, humor, adventure, serialized formats, word bubbles, panel borders….etc.

No doubt some comics folks flinched up there when I called comics a “genre”. And that does bring up a possible objection. Isn’t it wrong to think of comics as a genre, like science fiction? Shouldn’t they instead be compared to a medium, like prose or art or music? And if so, how useful is Rieder’s discussion of genre? Yes, genres may be webs of relations. But aren’t mediums defined formally? Art is always art; writing is always writing — shouldn’t, then, comics always be comics, whether created by the ancient Egyptians or on the internets?

I think the answer to those question is no, still pretty useful, not really and not really. Rieder does couch his formulation in terms of genre. But it works so well for comics that I think it forces you to either decide comics are a genre, or else to decide that the difference between medium and genre isn’t as great as it tends to seem. Egyptian hieroglyphs, after all, can either be writing, art, or comics, depending on which web of relationship you want to emphasize — and once you start thinking about webs of relationships, it’s in fact pretty clear that they aren’t that closely related to any current medium. Similarly, is a novel a genre? Is it a medium? It depends on how you look at it, surely — meaning, specifically, how you look at the web of relations of which it’s a part, and how those relationships are embedded in time and culture.

Comics straddles the line between genre and medium for various reasons — mostly having to do with the fact that (for reasons of commerce and credibility) it still hasn’t consolidated its cultural position the way science fiction has (as genre) or the way film has (as medium.) It’s betwixt and between, which makes the task of definition somewhat fraught and conflicted. But surely Rieder’s discussion leads to the conclusion that drawing these lines is always fraught and conflicted. A generic designation isn’t about dispassionately fitting a model, but about the more emotional task of finding and claiming one’s relations. The downside is that comics, as an origin and a form, doesn’t really exist; the upside, though, is that that leaves so many possibilities open for what comics can be.

Hi Noah,

I’m not sure I see the cash value of the distinctions you’re making here (and this has nothing to do with the fact that I can’t right now think of anyone who spends much time searching for the “first comic”).

Why would seeing genre or even form as a series of “family resemblances” — which is about as common a theoretical trope these days as one can find — make it misguided to look for origins, starting points, patterns of development, or predecessors?

After all, the set of currently accepted resemblances, themselves, have a history, have stages and patterns of development. It seems to make perfect sense to ask, “When did people start accepting Trait X as central to comics? Where did that trait come from? From what and from whom did it develop, and how did it gain formal/cultural dominance?”

Film theorists have been doing this with styles of cinema forever, and Tom Gunning and others have done the same thing with film’s formal qualities, thinking about how ideas of motion and space and projection were developing in such events as the phantasmagoria.

(Indeed, it is a Platonic narrative of absolute categories that has no need for origin stories, while historicized narratives demand and invite them. Darwin had to do away with the idea of fixed, immutable species in order to start thinking about species having an origin at all.)

But perhaps my larger question is this: why would we think that adopting a Wittgensteinian (or a sociological) approach would necessarily make our discussions about comics any more free and full of possibilities?

As Domingos has indicated elsewhere, sociological and historically contingent definitions can be just as restrictive and restricting and any formal checklist. In fact, from his vantage, it is only by getting away from the accepted “center” — and formal discussions are one way of doing this — that one can think about comics having an “expanded field” of critical and aesthetic consideration.

If folks are trying to follow what Peter’s talking about, Domingos’ discussion of definitions is here.

Peter, I’m pretty sure there isn’t any particular cash value to these discussions — but be that as it may, my experience has been that comics folks are pretty obsessed with defining comics, often formally. That’s certainly true in popular discussions like McCloud, but it’s also the case in something like Charles Hatfield’s Alternative Comics, which describes comics as an “art of tensions”, I believe (a definition I really don’t like, though that’s another discussion.) While it may be true that everybody in the academy knows about family resemblances, I don’t think that that’s a trope that has necessarily become a commonplace in more popular discussions of thinking about comics. I’d never heard of it anyway — which you can either take as a sign that I am ignorant and my views can be lightly passed over; or as a sign that it hasn’t maybe become quite the commonplace you’re suggesting. (I mean, I’m familiar with Judith Butler and the issues around repetition and origin in deconstruction — I talk about that some here from a different perspective.)

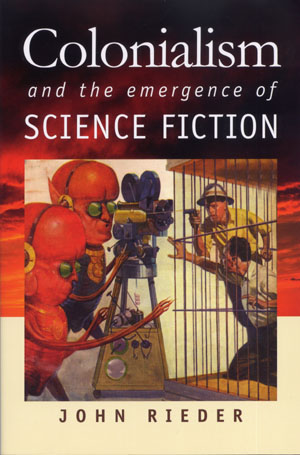

I actually quite like Domingos’ discussion, and I don’t see it as opposed to this one…and, indeed, I don’t really see it as opposed to most of what you’re talking about. For instance, I don’t see why my discussion would prevent you from asking questions like, ““When did people start accepting Trait X as central to comics?” Rather, the point is just that asking that question isn’t going to get you to any essence of comics, nor will it tell you what the “first” comic was, since by definition the first comic that has trait x central to comics is not going to be one in which that trait is central to comicness, but will instead be an innovation within a different tradition. To me, the point is that instead of trying to pin down an essence and drawing a line around what is or is not and can or can not be a comic, you look at relations and at how something might resemble comics. For instance, that image from Rieder’s book…I think it makes sense to think of that as a comic, or could make sense to look at that as a comic. The fantastic genre elements, the cartoonishness, the narrative and weird sense of temporal dislocation (is he shooting at the aliens now?), even the way the cage divides the image into two “panels.” There are resemblances, anyway…which seems like a more interesting thing to talk about than whether it is formally a comic in some essential way.

I don’t see Rieder’s points as necessarily precluding formalist rubrics either, incidentally — like I said, comics is defined in part by speech bubbles, panel borders, and serialization as well as by content such as superheroes and memoir.

Not sure I responded fully, but you’re welcome to press me further if not. In turn…I’m wondering what’s at stake for you exactly? Why would it be important to have an “original” comic? Do you find McCloud’s or Charles Hatfield’s discussion of these issues especially revelatory?

What about genres within comics, then? Superhero comics vs. sports comics vs. adventure comics vs. funny pages comics vs. Wacky Roommates Playing Videogames And Being Snarky comics vs. romance comics vs indie comics etc? If comics, as a whole, is a genre, then are all of those sub-genres? They’re more closely related to each other than to “comics” though, right?

Well, like I said, I think comics are sort of on the line between genre and medium. The way you can tell this is that people argue over whether they’re a genre or a medium — those terms are again, webs of relationships rather than formal absolutes, so if there’s a social confusion about which comics is, that’s something that I think it’s more useful to listen to rather than just “correcting” people for being confused.

Anyway — I don’t think there’s any contradiction in saying that you can have a genre with subgenres, or even a genre with genres within it. Along those same lines, I don’t think it’s necessarily wrong to think of “manga” as a genre within the American context (and perhaps to realize that manga is more solidly a medium within the Japanese context than comics are in the American one.)

And…I’m not sure that superhero comics (for example) are more related to superhero film than they are to other comics. It would depend…for example, Chronicle, a (quite good) found footage superhero film is arguably more like other found footage films than it is like mainstream comics.

Again, there aren’t really absolutes here. It’s more about what kind of argument you want to make or what discussion you want to have.

Leaving aside a lot of your other claims, I think it’s exactly right that “comics” is a family resemblance concept, not one constituted by necessary and sufficient definition. This is because, more or less, nothing is constituted by a necessary and sufficient definition. Death to the Classical Theory of Concepts! Death to the search for definitions!

So does that mean that some comics belong mainly to the “comics” web, while others belong more to the “roomates having misadventures” web? For instance? It’s my understanding that the postmodern objection to this would be that it privileges some “sub-genres” over others by putting them closer to the center of the comics web. Not that this doesn’t already happen, but at least a definition based on formal qualities evens the playing field a little bit.

Oh ya, I remember the manga-is-a-medium-not-a-genre argument from back when Tokyopop announced it’s “Original English Manga (OEM)” line of comics. There was a lot of debate about the appropriateness of that label, when Korean manga is “manwha” and there is not one single “manga” style because manga is a medium in Japan and not a genre, but at the same time there are some more common elements and a web of influence that stretches to NA… Stephanie Folse (magatsu.net, telophase@livejournal, the provider of my webspace, and a columnist here) probably remembers the arguments better than I do, since she had a column with Tokyopop at the time and has self-published a couple OEM titles since.

Well…I don’t know that the web needs to have a center. More like nodes, perhaps, which shift over time, and/or depending on where you’re looking at them from?

Incidentally, the following three claims are entirely compatible with one another:

1) The concepts of “comics” are characterised by a loose set of similarity relations between features (i.e. family resemblance)

2) comics are a medium (the features in question might be formal ones)

3) the set of similarity relations that characterise modern concepts of “comics” are fortuitous, the product of various accidents of history and sociology

I can tell that those claims are mutually compatible, because I believe all three, and, of course, I never believe contradictions…

Family resemblance concepts — or, in Roschian terms, prototype concepts — can have “centres” in the sense that some examples are judged as more typical instances of the comic. Fantastic Four or Garfield are, for better or worse, more central in many modern concepts of comics than, say, the works of Lynd Ward or Enrico Caruso. (Domingos, I hope you’re grateful that I’m feeding you a straight-line like that)

Yeah, but if it’s about connections to other works, doesn’t that still mean that a work is more “comics-like” if it has more connections to other works that are also more “comics-like” ie also have more connections?

On preview, what Jones said!

Jones, there’s always the theory theory of concepts, which kind of saves essentialism.

The idea that the distinction between genre and medium is content vs. form is a neat one…but does it always hold true? I’m not so sure… I think in some ways distinctions between form and content may be somewhat arbitrary too. As with manga, which looks like a formal designation in Japan, and more like a genre one over here….

Subdee, I don’t think the goal is (or has to be) to figure out what is more “comics-like.” A comic could certainly be more central to a particular discussion — but that isn’t the only discussion. Tezuka is absolutely dead center for any discussion of comicness in Japan — but occupies a somewhat different place if you’re talking about American newspaper comics. Or reverse those with Garfield.

One of the things I like about Rieder’s definition is that it’s really not about hierarchies of essences, I don’t think. Thinking in terms of connections is a way to think in terms of different connections and relationships, not a way to say, “well this has more connections, so it’s more of a comic.”

rhizomes? but that’s not much like the prototype theory, which this sounds more like.

Eric, could you be a bit less gnomic?

This…” Well…I don’t know that the web needs to have a center. More like nodes, perhaps, which shift over time, and/or depending on where you’re looking at them from?” sounds like the Deleuze/Guattari rhizome concept.

But I think this/your notion sounds more like prototypes, as described above…

“Family resemblance concepts — or, in Roschian terms, prototype concepts — can have “centres” in the sense that some examples are judged as more typical instances of the comic. Fantastic Four or Garfield are, for better or worse, more central in many modern concepts of comics than, say, the works of Lynd Ward or Enrico Caruso. ”

“Nodes” is more decentered…but I think it makes more sense to think in terms of “prototypes” for family resemblances….which means there is a “center” of sorts, but all kinds of stuff are “close enough” to the center to make it into the family.

It just seems like what the center is, or how it’s defined, can vary depending on your perspective or what exactly it is you want to talk about. I mean, there are surely ways of thinking about comics where Tezuka would be the center, and others where Garfield could be the center, and others where Superman would be the center. Those are all pretty different visions of comics — though not mutually exclusive ones, of course.

————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

If sci-fi is a web of resemblances though, that has some surprising implications. Specifically, if the genre is the web, it can’t exist before the web.

————————–

A genre can’t exist without there being several works along that vein; however, a First Science Fiction Work Ever could exist all by its lonesome; ’til others come along to join it.

As you’d noted in a recent HU thread:

———————–

Noah Berlatsky had said:

Midsummer Night’s Dream really is not fantasy — in part because people don’t think of it as fantasy, and it hasn’t been an important touchstone for people creating fantasy works…

————————

To which I responded:

————————-

That a work can be “an important touchstone for people creating fantasy works” is an interesting point; certainly “The Lord of the Rings” created a template that was most assiduously followed and imitated. (The aforementioned, massively successful “Sword of Shannara” series clearly in that mold.)

Then there’s Edgar Allan Poe’s creation of the first detective story; its C. Auguste Dupin — well-off, eccentric, brilliant, using logic to solve the mystery, considering the police unimaginative plodders — providing the template for many who followed, its success inspiring other authors: http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/first-detective-story-is-published .

…And that’s how “genre conventions” are born.

————————-

Back to the present:

————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

There can’t be a point of origin, because a point isn’t a web.

————————-

(???) One might as well say, “A line can’t have a point of origin, because a point isn’t a line.”

Would not a work which truly was the “important touchstone” be the point of origin of a genre? “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” the “cosmic egg” from which sprang the detective genre (as in the Big Bang theory the universe burst from an unimaginably compressed elementary particle):

————————–

Genesis: 1841

Edgar Allan Poe was the undisputed “Father” of the Detective Story. He created so much that is of importance in the field — literally creating the template for all of detective fiction to follow. (Years later, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was to say that Poe “was a model for all time.”)

In just three stories, Poe created the amateur detective and his narrator friend, the locked-room mystery, the talented but eccentric amateur sleuth outwitting the official police force, what Haycraft calls the “catalogue of minutia,” interviews with witnesses, the first fictional case of an animal committing a perceived murder, the first armchair detective, the first fictional case which claimed to solve a real murder mystery previously unsolved by police, the concept of hiding something in plain sight so that it is overlooked by everyone who is searching for it (except for the detective, of course), scattering of false clues by the criminal, accusing someone unjustly, the concept of “ratiocination” (later called “observation and deduction” by Sherlock Holmes and others!), solution and explanation by the detective, and more. Other stories by Poe introduced cryptic ciphers, surveillance, the least-likely person theme (in one case, the narrator of the story is the murderer!), and other ingredients that have spiced up many a recipe for a crime story.

————————–

http://www.worlds-best-detective-crime-and-murder-mystery-books.com/1841.html

From “Mr. Google,” how a spider builds a web: http://ednieuw.home.xs4all.nl/Spiders/Info/Construction_of_a_web.html .

A line isn’t a web, but a web starts out as a line…

SF, though — appropriately — evolved into being. From fantasy, to moderately science-based…

————————–

Cyrano de Bergerac’s works L’Autre Monde: ou les États et Empires de la Lune (The Other World: or the States and Empires of the Moon) (published posthumously, 1657) and Les États et Empires du Soleil (The States and Empires of the Sun) (1662) are classics of early modern science fiction. In the former, Cyrano travels to the moon using rockets powered by firecrackers and meets the inhabitants. The moon-men have four legs, musical voices, and firearms that shoot game and cook it.

His mixture of science and romance in the last two works furnished a model for many subsequent writers, among them Jonathan Swift, Edgar Allan Poe and probably Voltaire…

————————-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyrano_de_Bergerac

…getting less far-fetched, frequently more scientifically plausible, as science progressed.

Poe’s detective stories aren’t detective stories though, because the detective story genre didn’t exist. They’re literary short stories partaking of the current romanticism. They’re not genre works any more than Frankenstein is a genre work, because genre requires a web of resemblances, and there wasn’t a web at the time — or there was, but it wasn’t the web we have now.

Rather than looking to a single genius as the origin, it can be more useful to think about how different tropes took hold…which might, for instance, help you think about ways in which Poe is different than other detective stories rather than a precursor…or to see elements of the detective story in other works before Poe, perhaps.

To be honest, Charles, I’ve never really understood how the theory-theory was supposed to do the work that a theory of concepts is supposed to do and nothing I ever read about it — and I read a lot, back in the day — illuminated me…but if you’re thinking about that Medin/Keil stuff on biological essentialism, it seems highly unlikely that people have that kind of essentialism about something like “comics”

————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Poe’s detective stories aren’t detective stories though, because the detective story genre didn’t exist. They’re literary short stories partaking of the current romanticism. They’re not genre works any more than Frankenstein is a genre work, because genre requires a web of resemblances, and there wasn’t a web at the time…

—————————

Alas, “idealism” in action!

People comes across a striking, compellingly-phrased idea. Whether it’s accurate or not makes little difference. Indeed, “real world” accuracy, with the detail and complexity that entails, is actually a drawback. People never listen to guys like the one in the middle here, as depicted in Tim Kreider’s “My Slogan”: http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/MySlogan.jpg .

Those peddling their grand idea want to convince others, and thus minimize, glide over, explain away or ignore the “sticking points” or flaws (as psychology explains, even blinding themselves to those flaws in their brainchild), and evangelize their simplistic message.

Which the masses, far more swayed by a simple message than a complicated one (as shown by the way fundamentalist religion and churches thrive and grow, while liberal ones dwindle away), then adopt.

The result: http://freechristimages.org/images_Christ_life/BlindLeadingTheBlind_Bruegel.jpg .

I have no trouble with

—————————–

…Rieder…argues that a genre is best understood not through a strict formal definition, but rather as a group of texts that bear a “family resemblance.” The term is from Wittgenstein, and Rieder quotes a further explication by scholar Paul Kinkaid:

science fiction is not one thing. Rather, it is any number of things — a future setting, a marvelous device, an ideal society, an alien creature, a twist in time, an interstellar journey, a satirical perspective, a particular approach to the matter of story, whatever we are looking for when we look for science fiction, her more overt, here more subtle — which are braided together in an endless variety of combinations.

——————————

Or even with

——————————-

Science-fiction is then a “web of resemblances.”

——————————-

But then, the bottom falls out!

——————————-

If sci-fi is a web of resemblances though, that has some surprising implications. Specifically, if the genre is the web, it can’t exist before the web. There can’t be a point of origin, because a point isn’t a web. For there to be family resemblances there has to be a family.

———————————

I’ve already dealt with the earlier statements. Let’s consider “For there to be family resemblances there has to be a family.” This is embodied in the most famous example in history, the “Habsburg lip.”

———————————

Pathologic mandibular prognathism is a potentially disfiguring, genetic disorder where the lower jaw outgrows the upper, resulting in an extended chin.

The condition is colloquially known as Habsburg jaw, Habsburg lip or Austrian Lip (see House of Habsburg) due to its prevalence in that bloodline. The trait is easily traceable in portraits of Habsburg family members. This has provided tools for people interested in studying genetics and pedigree analysis. Most instances are considered polygenetic.

It is alleged to have been derived through a female from the princely Polish family of Piasts, its Masovian branch. The deformation of lips is clearly visible on tomb sculptures of Mazovian Piasts in the St. John’s Cathedral in Warsaw. However this may be, there exists evidence that the trait is longstanding. It is perhaps first observed in Maximilian I…

——————————–

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prognathism

So, before there was a family with a characteristic malformation to provide the “family resemblance,” there was an individual; Maximilian I, or “a female from the princely Polish family of Piasts,” or some unknown other, who possessed and passed on that highly distinctive trait.

To circle back again:

————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Poe’s detective stories aren’t detective stories though, because the detective story genre didn’t exist. They’re literary short stories partaking of the current romanticism. They’re not genre works any more than Frankenstein is a genre work, because genre requires a web of resemblances, and there wasn’t a web at the time…

—————————

I’ve got the whole series of delightful “Uppity Women” books (one entry: http://www.amazon.com/Uppity-Women-Ancient-Times-Vicki/dp/1573240109 ).

—————————-

Our age doesn’t have a lock on outspoken women, as Vicki Leon proves in this impudent, flippant history of the Middle Ages. In the 1600s, Lady Castlehaven charged her husband with rape and had his connubial rights–and head–removed. Prioress Eglentyne, who appears in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, fell afoul of clerical colleagues by ignoring rules about “dress, dogs, dances” and worse yet, “wandering in the world.” And let’s not forget Isabel, Queen of Castile, patron of Columbus, and wife to Ferdinand. Her marriage motto was “They rule with equal rights and both excel, Isabel as much as Ferdinand, Ferdinand as much as Isabel.”

—————————-

http://www.amazon.com/Uppity-Women-Medieval-Times-Vicki/dp/1573240397/ref=pd_sim_b_1

Now, if a woman in olden times argues that women should have equal rights and freedoms, are capable of being the intellectual equals of men and wielding power, etc., would you say “she’s not a feminist, because feminism hadn’t been invented yet”?

————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

it can be more useful to think about…ways in which Poe is different than other detective stories rather than a precursor…or to see elements of the detective story in other works before Poe, perhaps.

——————————

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Detective_fiction explains how the antecedents of detective fiction differed from what Poe created; and that “true detective fiction is more often considered in the English-speaking world to have begun in 1841 with the publication of “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” itself, featuring “the first fictional detective, the eccentric and brilliant C. Auguste Dupin”. Poe devised a “plot formula that’s been successful ever since, give or take a few shifting variables.”

Also, this “Genre Characteristics Chart” might be of interest: http://tinyurl.com/cjwfjjp . (No SF, alas…)

Nothing is smack in the center, but all kinds of stuff cuddle up together ’round it (like Tezuka, Superman, and Garfield—nobody would argue any of this stuff isn’t comics)…

Poe’s stories are detective stories NOW…they just weren’t then. It’s the whole Kafka and His Precursors thing

Actually, people do occasionally argue that manga isn’t comics. And McCloud says Dennis the Menace isn’t comics, which most people would see as pretty centrally comics, I’d imagine. Sooooo….

I feel that a ‘family resemblance model’ that somewhat conflates genre conventions and formal conventions is really useful, partly because it suggests how certain traits were developed, codified, and ritualized over time. Or how certain traits were lost. I suspect that the American comic book was born as a field, rather than a cute trick, in that people wanted to read and draw more superhero, crime and funny animal stories, and that the formal conventions sort of came along for the ride. But maybe not… there seems to be an incredible amount of diversity in the content of early comic broadsheets, and a lot of the creators seem to use their recurring characters and plots as a thread to run through formal experiments. I think formal definitions of comics (like Cloud’s) ignore the social and psychological context of how they came to be, and can miss the boat on being insightful about what comics are.

I’ve always been uneasy with McCloud’s theory, because it priveleges the form.

I don’t see many arguing manga isn’t comics…but in a family resemblance model, it wouldn’t be “in or out”–it would be “here’s the things everyone agrees are comics” and then concentric circles around it. So…if someone wants to argue manga isn’t sitting in the center of circle, I think it would be hard to argue manga doesn’t “resemble” comics…so it makes it into the circles. Same with Dennis the Menace. If you have a strict “this is the definition”–then stuff can fall outside of it. If you have a “prototype” model, then single-panel comics like Dennis (I think he actually uses Family Circus–but whatever) are not smack dab in the middle of the model, but they still fit in the circles…

The example I remember reading about is of birds…Most people think of birds as flying, so flying birds are closer to the center of the prototype…but then ostriches, emus, penguins, etc. are just “further away from the center–or prototype”–but they’re still birds. Airplanes, maybe, are further from the bird-prototype, but there’s still some family resemblance (and some folks colloquially refer to them as “birds”). A duck-billed platypus is on the outskirts of these circles too, maybe (on the strength of the duck-bill and the egg-laying)…but my left shoe probably wouldn’t make it into the circles at all…no family resemblances.

Oops! I didn’t see that fragment left over at the end…

It sounds like a family-resemblance approach coincides with Arthur C Danto’s institutional or “artworld” theory in some places. Bart Beaty forwards this idea in his book Comics Versus Art. From his book:

“George Dickie, arguably the most prominent of the advocates of institutionalism, argues in his 1975 book Art and Aesthetic that a work of art is an artefact presented to the art world public, and that the art world public is a set of individuals who are prepared in some degree to understand an object that is presented to them as art.”

A bit tautological, but more importantly, an organic feedback loop. Comic’s borders lie where comic’s audience draws them, which is done socially. Some communities, following McCloud, might now reject Dennis the Menace but include the Bayeux Tapestry, but most would accept the Dennis the Menace reprints by Fantagraphics as within the orbit. As well, the niche-ier the ‘world,’ the more they can extend their own borders without recourse to wider culture, (think of how much ‘art’ is not considered ‘art.’) This honors the creative flexibility you see in comics, where the motivation to make or read the form of ‘comics’ is rolled up with desire for its genres, and the centrality of toys and collectibles,(character-based commercial franchises having always been a big part of it too.) And, I think, the inclusion of fan-fiction that is not comics, but based on comics, into the chain of consumption. Sorry this is really scatter-brained… but I think that while an institutional “Comicsworld” sheds some light on creator and consumer behavior, it’s fleshed out by a family resemblance or ‘prototype’ model that can track how certain formal and genre traits in commics and non-comics media historically have faired.

The birds analogy seems pretty bad, since birds actually can be classified using rigorous formal scientific definitions. I mean, yes, there’s wiggle room in science too, but you’re talking about a much, much more comprehensive and (again) rigorously defined model than with art. Ostriches and emus are classified as “birds” on the basis of things like DNA evidence and specific morphological traits, not on the basis of a more generalized “family resemblance.” (The extreme case here is math; prime numbers are defined (almost?) purely on a formal basis.)

I mean, I agree manga are comics…but if you poke around blogs and comments enough, you’ll see folks arguing that they’re not the same, or shouldn’t be considered the same. And unlike with birds (where you can point to authoritative scientific formal definitions to explain why an ostrich is a bird but an airplane is not) there isn’t any rigorous argument you can use to disprove them — except, “this looks like that.”

Kailyn, that all sounds right to me…but could you expand on this?

“can track how certain formal and genre traits in comics and non-comics media historically have faired.”

I’m not sure I’m following you; is there an example you could give?

I’m not sure where the birds example comes from, but the concept I remember Wittgenstein discussing as “family resemblances” is games, which might be a little closer to genres.

I think Wittgenstein used sports as his example (or at least that’s what Riener says.)

Okay, maybe I’m misremembering Wittgenstein. Or maybe Riener read something else, but in Philosophical Investigations at least, I’m pretty sure the discussion focuses on games (which can include sports but aren’t equivalent unless you’re a Shonen Jump manga artist, in which case all human activity reduces to sports tournaments).

Science is just a discourse that establishes “what counts as a bird”—A discourse that decides on what is defined as “fact.” I don’t see the “birds have science to define them” as particularly convincing.

How are “morphological” features any different from “formal features.” They’re both arbitrary. You choose x amount of features to define y thing. Science does the same thing with birds…And, yes, you can think of birds as “they’re in or they’re out”, but you can think of comics that way too. I would say either one makes more sense with a family resemblance model. The idea than an ostrich is the same thing as a pigeon is no more accurate/descriptive than Superman is the same thing as Signal to Noise. Just because defs. of genres, media, and aesthetics are relative doesn’t mean scientific defs are concrete/objective. There’s just more agreement out of the interpretive community. Consensus doesn’t equal objectivity.

It’s not objectivity, but it’s much more rigorous. The consensus is much more formally grounded, and much more clearly defined. Since all we’re talking about anyway is interpretive communities, the fact that science uses much (much, much) more rigorous formal definitions in its interpretive community ends up effectively being a qualitative difference, not just a quantitative one.

I mean, I like Feyerabend. Science’s categories can definitely be disputed in various ways. But I don’t think it’s useful to think of comics as birds when birds can be rigorously defined through formal qualities, and comics really can’t. You don’t need family resemblances to classify a bird as a bird; you’ve got something that looks a lot more like actual family trees, which are similar in some ways, but I aren’t the same thing, I’d argue.

I just in general think it’s a problem to compare aesthetics and science without a lot of qualifiers. They’re both interpretive frames, but they’re interpretive frames that work pretty differently.

Thanks Noah– I think they are compatible lines of thought.

In art history and theory, Danto and company have switched their focus from a definition of art, to a examination of how artefacts are percieved as art. Institutionalism comes down to ‘art’s whatever you make it,’or really, what the institution decides to term art, and the public is willing to understand as art (failures can happen at every step, such as the failure to integrate comics into an art context, or be percieved by the ‘art world’ as art.) Yet I’m not sure how much mileage exists in this perspective shift alone, (I really should read more.) After conceding that art is whatever you want it to be (or comics are whatever you want them to be,) does institutionalism give you any tools to figure out when and where it fails?

That’s where I’m excited by the idea family resemblances and prototype theory. By conflating formal traits and genre/content traits into equal-footed memes,(I really, really don’t know Semiology that well, but I might be stepping into code territory as well,) I think you can trace the history of which certain ‘memes’ were adopted, became focal points, became ritualized, or were dropped. Along Noah’s point, there was no BAM! First Comic! but a few central memes that were institutionalized together, and determined what their creative offspring would look like, and how they would rebel. And I think these memes were both formal (juxtaposed images yada yada) and content based. An early definition of comics as ‘following a central character that become’s the reader’s dear friend’ (I’m paraphrasing) might be not completely off…

I’m working on making these thoughts clearer for a post in the Comics and Art vein…

You don’t need family resemblances for birds, but it’s a viable alternative. You don’t need it for comics either. It’s just an exercise in trying to affix signifiers to signifieds. No cash value in it, as Peter says. Anyway, this will settle this question once and for all… In the Mike Hunter tradition..

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red-legged_Seriema

Anyway, my linking of birds to prototype theory comes from the book More Than Cool Reason, which is an effort to define/discuss metaphors…which I read some 14 years ago. At least I think it does…didn’t double check

http://www.amazon.com/More-than-Cool-Reason-Metaphor/dp/0226468127

“birds” are the classic example used to illustrate prototype theory; they feature prominently in some of the early experimental work by Rosch.

And, at least based on the literature I was familiar with five or six years ago, scientists don’t “define” birds on the basis of DNA or anything else. The standard modern account in biology (again, based at least on how things stood half a dozen years ago) is that species and other higher order taxa don’t have an essence and can’t be given an informative definition; they’re just “defined” as animals in such-and-such a a chunk of the evolutionary tree, descended from a particular common ancestor. We use morphological traits (has feathers, a beak, etc.) to classify things as birds, but categorization and definition are two different things.

The rhizomatic metaphor doesn’t seem all that different from the prototype/family resemblance one: it’s something like a connectionist way of modeling the latter. The stronger the connection (the higher the weight) between feature nodes, the more two concepts within a family “resemble” each other.

Anyway, Jones, a major problem with prototype theories is coherence, right? It’s a problem with radical empiricist views since the beginning. At best, the theories proponents have similarity, but that’s not the basis for all of our categories (I’m flailing for some examples right now, but there’s that fictional example from Borges that Foucault used to quote). Furthermore, Nelson Goodman, for one, went to great lengths to demonstrate that similarity is not an end in itself, but rests on other notions which make things similar. A dolphin isn’t exactly similar to a man, but they both belong to some of the same categories, once we have some theory in place. Okay, that’s the biological example that you mentioned, but surely some of the expanded field examples of “comics” is not driven by perceptual atoms knocking about in the brain, but by a heavily theoretical and historically informed perception (e.g., Domingos).

“theories proponents” should be “theory’s proponents”

Hmm…okay…but I think surely you start to get into trouble if you’re trying to say that the family resemblance allows you to categorize airplanes as birds? It just seems like there’s a pretty big difference in terms of the discourses you’re dealing with between saying, maybe manga might not be classified as comics, and saying airplanes are birds. You’ve got much more powerful ways of saying that the second is just wrong, it seems like — which isn’t everything, but is surely something.

Maybe it gets at why it makes more sense to think of comics as rhizomatic? I mean…biological categories and aesthetic genres may themselves have distant family resemblances, but it seems like it’s more on the order of birds/airplanes than comics/manga. You’re really looking at different institutions, different discourse communities, different procedures for establishing truth, different perspectives, different questions… I just feel like trying to fit a definition of comics to a scientific model is potentially even more flattening than using McCloud’s definition.

That all sounds right to me, Noah, because it points to needing something over family resemblances to figure out why we classify things like we do. Why don’t we classify birds as being closer to humans than airplanes? Well, because it’s more than resemblance.

jesus christ: reverse ‘humans’ and ‘airplanes’ in that rhetorical question.

Also, it’s funny that categorization is so fascinating to me, but I don’t much care about what classifies as an X (film, comic, etc.). Just define your terms as needed at the beginning and get on with the important stuff. Comics nerds probably agree on 99% of what objects they’re calling a comic, so why does this debate go on? Blah.

I mean, to me the thing that we tend to add in comics is a sense of history, right? And a reference to social factors (i.e., what other people call comics.)

I don’t necessarily care about what is classified as what when…but the not caring has ideological and practical consequences. As in, this is a comics blog that has posts about a lot of things that aren’t comics — and that “not comics” doesn’t map onto “geek culture” the way that it typically does for sites that focus on comics but not-comics.

Similarity of basic perceptual features is not the only type of similarity used in prototype theories. In principle, any kind of feature can support judgements of similarity; in any case, features like “breathes”, “eats”, “dies”, “reproduces”,”has blood”, “grows”, “has eyes”, “has legs”, “moves by itself”, “shows intentional action” etc. all argue for classifying “birds” as closer to “humans” than to “airplanes”, and if you don’t see a problem in making similarity-judgements over the feature “flies”, you shouldn’t see a problem in making similarity-judgements over those ones. IIRC, prototype theory also allows for certain features to be weighted more heavily than others in categorization (so you could rate those features more heavily in the concept “animal”).

…shit, I don’t mean to come off like I have a particular brief for prototype theory. It almost certainly can’t provide a complete account of concepts, or even of categorization; IMO there’s way too much empirical evidence in support of all three contemporary models of concepts [prototype, theory, and exemplar] for any one of them to be the whole story. (this was the upshot of Gregory Murphy’s Big Book of Concepts, if memory serves). For instance, what determines how features get weighted in similarity-judgements would often have to be something theory-based, as per the theory-theory. And, as the neo-classicists argued in the 80s, there’s got to be a distinction between categorization procedures and membership criteria — even if you don’t think there are criteria as such, there’s just got to be some distinction in that vicinity.

Not sure I understood all that…but to the extent I did, I’m not entirely convinced that Rieder is arguing for a prototype theory, or for a pure prototype theory anyway. I mean, his account of genre — focusing on things like, there can be no origin, doesn’t even seem like something that would come up if you’re talking about bird classification. And he also talks about historicizing, and the fact that genre relationships would change over time — again, the historicizing doesn’t seem like it would be something that would matter much with birds.

I mean, is Wittgenstein seen as the originator of protoype theory? I sort of feel like if that was exactly what Rieder was talking about, he might have said so….

——————

Noah Berlatsky says:

…And McCloud says Dennis the Menace isn’t comics, which most people would see as pretty centrally comics…

——————

Eddie Campbell superbly argued for (though not using that not-yet-coined term), the “family resemblance model.” First done back in that Comics Journal Message Board, a forum despised by its creators for its lapses into messy argumentativeness, and finally — for all the valuable portrait of a time it contained — flushed down the cyber-toilet.

(Must…Google!) Some Campbell thoughts on the subject, from http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Comics:

——————

– comics… are simply a tradition.

– I don’t think that we should seek to define comics on a formal basis. I think that some of the best comics do not involve “sequential images” which is the basis of every formal definition of comics.

– …the concept of what comics is gets narrower as we go along. Each writer on the subject who defines comics wants to exclude something. McCloud excludes the single panel so Family Circus and Far Side are out. Blackbeard says there must be word balloons so Prince Valiant is out. Harvey says there has to be a visual-verbal balance. Somebody else says there must be no redundancy of information with words and pictures repeating each other. This is crap. Pictures have illustrated words and words have explained pictures since the beginning of time. Somebody reads a dull comic and extrapolates rules from it. Who do they think they are? There are all these people trying to be the rule-makers and the end result is bad for the art of Comics.

-The syllogism that says “Comics are sequential art, Trajan’s column is sequential art, therefore Trajan’s column is comics” is such a glaring fallacy that I’m surprised it’s gotten this far.

——————

——————

Kailyn says:

I feel that a ‘family resemblance model’ that somewhat conflates genre conventions and formal conventions is really useful, partly because it suggests how certain traits were developed, codified, and ritualized over time.

——————–

I quite agree; it’s that ” ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ is not a detective story, because the detective story genre did not yet exist” argument which sticks in my throat like a crossways chicken-bone.

———————

eric b says:

Poe’s stories are detective stories NOW…they just weren’t then.

———————-

Um. Do they not have all the qualities of detective stories?

Maybe it’s that I just finished reading a “New Yorker” article on Anne Applebaum’s “Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe” before getting online, but this argument sure reminds of “the individual is nothing, the movement is everything” thinking. Leading to nonsense such as, “Mary Wollstonecraft was not a feminist, because she wasn’t part of the feminist movement.”

Which sure has the benefit of giving those within the movement the power to cast into the Outer Darkness those who do not conform (“Trotsky is not a real Communist, because he disagrees with Stalin”). And also creates a “clubhouse” feeling, with established SF writers resentful of interlopers from the Literary world (seen as slumming, or condescending) daring to venture into their domain.

———————–

eric b says:

The idea than an ostrich is the same thing as a pigeon is no more accurate/descriptive than Superman is the same thing as Signal to Noise. Just because defs. of genres, media, and aesthetics are relative doesn’t mean scientific defs are concrete/objective. There’s just more agreement out of the interpretive community. Consensus doesn’t equal objectivity.

———————–

———————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

It’s not objectivity, but it’s much more rigorous. The consensus is much more formally grounded, and much more clearly defined. Since all we’re talking about anyway is interpretive communities, the fact that science uses much (much, much) more rigorous formal definitions in its interpretive community ends up effectively being a qualitative difference, not just a quantitative one.

————————

The mind reels…Noah is defending science??

Not exactly defending it…it’s a system with particular rules which are different than those of other systems. It’s not objective truth…but that doesn’t mean there can’t be different kinds of truth and different kinds of systems.

My attitude to either comics or science fiction is that of the Supreme Court justice to obscenity: “I know it when I see it.”

Sometimes it’s easier than others, though:

http://i.telegraph.co.uk/multimedia/archive/01474/island_1474483i.jpg

http://www.cyberpunkreview.com/images/gattaca13.jpg

Re Noah’s “there [can] be different kinds of truth and different kinds of systems,” there can also be different kinds of intelligence. From Tim Kreider: http://www.thepaincomics.com/weekly010411.htm

And science may not be “objective truth” in the sense of being utterly omniscient and all-encompassing, but the countless facts it’s built upon, such as “the heart pumps blood around the body”; “the Earth revolves around the Sun”; “the boiling point of water at sea level is 100 degrees Centigrade”; or…

———————–

The full song [of the Red-legged Seriema or Crested Cariama] consists of three sections:

1. Repeated single notes at constant pitch (1,200 to 1,300 Hz) and duration but increasing tempo

2. Repeated two- or three-note subphrases of slightly higher pitch with increasing tempo

3. Subphrases of up to 10 notes, shorter ones rising in pitch and longer ones falling, two-subphrase combinations increasing in number of notes and tempo and then decreasing in tempo.

———————

Tip of the hat to eric b; from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red-legged_Seriema

…sure are as “objective” as can be.

Where science falls from objective truth is when making sweeping assertions from bits of information that fail to take into account greater complexities and individual biases. I.e., saying that, “since African-Americans routinely score lower in IQ tests than whites, therefore their race is inherently inferior, and improved education and nutrition during childhood would be a waste and make no difference whatsoever.”

Pingback: ‘Holy Crap’: The Flawed Notion That Novels Can Transcend Genres