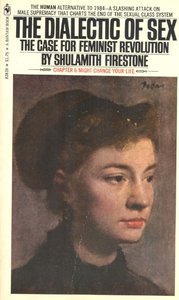

“Just as the end goal of socialist revolution was not only the elimination of the economic class privilege but of the economic class distinction itself,” wrote radical feminist Shulamith Firestone, “so the end goal of feminist revolution must be … not just the elimination of male privilege but of the sex distinction itself: genital differences between human beings would no longer matter culturally.” This same understanding exists, if in a less cogent form, in Paul’s letter to the Galatians. Galatians 3:28 makes the oft-quoted assertion, “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Following as it does several denunciations of a virtue that appeals to law rather than spirit, this statement of universality is not lightly thrown out, but rests on Paul’s core conception of salvation (“conception” being a key word).

“Just as the end goal of socialist revolution was not only the elimination of the economic class privilege but of the economic class distinction itself,” wrote radical feminist Shulamith Firestone, “so the end goal of feminist revolution must be … not just the elimination of male privilege but of the sex distinction itself: genital differences between human beings would no longer matter culturally.” This same understanding exists, if in a less cogent form, in Paul’s letter to the Galatians. Galatians 3:28 makes the oft-quoted assertion, “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Following as it does several denunciations of a virtue that appeals to law rather than spirit, this statement of universality is not lightly thrown out, but rests on Paul’s core conception of salvation (“conception” being a key word).

The erasure of distinction between Jews and Gentiles is what Paul discusses back in chapter 2; it is a letter to a church, after all. But the other two distinctions, the ones involving the inferior classes of slaves and women, not to mention children, are addressed simultaneously in the fourth chapter. And, as feminists did almost two millennia afterward, he rooted this hierarchy in the system of inheritance that forms the core of patriarchy. A child of a wealthy man is like a slave until coming of age, Paul reminds the Galatians, and the life and crucifixion of Christ means that, in the eyes of God, nobody is truly a child nor a slave any longer. He then moves on to expressing his concern for them, and compares himself to a mother in labor.

Paul continues very deliberately to pursue the childbirth metaphor. He offers two mates of Abraham as models– one slave, one free. Each bears a son– the first, Hagar, “of the flesh,” the second, Sarah, from “a divine promise.” Sarah is the mother of Isaac, a patriarch of Israel, but Hagar, the mother who is a slave, is described by Paul as the mother of the earthly Jerusalem, which lives in slavery (under the Law and under the Roman heel).

An interesting parallel to this (and to other Biblical pairs of sons) exists in Mark Twain’s Pudd’n’head Wilson, in which two children, one slave and one free, are switched by the mother of the slave child at birth. The free child who becomes a slave is hardworking and noble, while the slave child who becomes free is vicious, irresponsible, and, eventually, a murderer. The use of fingerprints in solving the murder might argue for a racial theory of behavior, but this conclusion is derailed by the introduction of a pair of black European twins into the story, who are falsely accused of the crime committed by the almost-entirely Caucasian son of the slave woman. The system of power and paternity (i.e. patriarchy) on which the entire system depends becomes almost a character at the end of the novel, when the murderous son has his slave status reinstated and is sold into the living hell known as “down the river.”

But, lest it be deemed a fit and just law, it is also this patriarchy that leaves the slave mother sorrowful in repentance, and the freed son lonely in his enfranchisement, without a secure sense of himself. That such an oppressive law would be seen by Paul as identical with the system of inheritance is made explicit in chapter 27 of Galatians, in the verse from Isaiah he quotes to decree all the faithful to be the free children of Abraham’s infertile wife Sarah.

Be glad, barren woman,

you who never bore a child;

shout for joy and cry aloud,

you who were never in labor;

because more are the children of the desolate woman

than of her who has a husband.

Firestone’s major work, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution, focused a great deal on the central necessity of relieving women of asymmetrical duties in regard to childbirth and child-rearing. “A mother who undergoes a nine-month pregnancy is likely to feel that the product of all that pain and discomfort ‘belongs’ to her,” she wrote; also, “If women are differentiated only by superficial physical attributes, men appear more individual and irreplaceable than they really are.” Freedom, both for Paul and for Firestone, rests not on the acts of privileged individuals, but of erasing the very structure of privilege. That one comes through faith and one comes through revolution is not a minor consideration, but in both cases, as with Twain, the contradictions on which the structure rests must be brought to light in order to begin the creation of a new reality.

I really like this. I think I’ve mentioned this to you before, Bert, but it reminded me again of Stanley Hauerwas’ argument in his memoir that Christians aren’t necessarily meant to have children, inasmuch as children are always an excuse, incitement to violence justified on the basis of protecting them.

The queer psychoanalysis book I’m reading by Adam Phillips and Leo Bersani, with the regrettable title Intimacies, talks about the paradox of the ego– how love bridges boundaries and expands the ego, but ultimately annihilates it. Kids are a good way to shore up your ego-boundaries while still having plenty of property to defend.

Yes…though it’s also true I think that for man people kids are a motivator for peace rather than for violence.

Sure, maybe, if you say so. The great heterosexual child-future (the current version of the pure bloodline myth) is ever so frequently one that actual children’s blod is shed in the name of, though, that children, in and of themselves, can hardly be seen as anything ensuring peace.

I don’t think they ensure peace. And lots of horrible things, most notably killing children, is done in the name of protecting children.

But people who work against war often do so in the name of children as well. Pacifist churches pass their traditions down in part through their children. The Civil Rights movement was not trivially about people wanting a better life for their children.

Kids affect people’s lives in complicated and fairly thoroughgoing ways. I wouldn’t want to idealize it, but I think the alternate tendency to demonize it, or see it as intrinsically negative, is probably not the way to go either. I think Hauerwas would agree with that probably. Certainly, I think from his memoir he feels like his own child has been a huge benefit to his life and his faith.

Well, I’m not too worried about anyone demonizing reproduction. It’s sort of like the anti-PC fear– it’s not that the cultural tendency labeled “PC” is a thoroughly endearing one, it’s more that the enemy it identifies is not entirely a phantasm.

Which wasn’t the point of my piece, by the way, nor of the Dialectic of Sex– not even of Paul, although he sure liked celibacy.

“Well, I’m not too worried about anyone demonizing reproduction.”

Not even Roman Polanski?

Mentioning Roman Polanski in a discussion of children really kind of is a fart in church. I do love Rosemary’s Baby though.

I expected nonsense from her when hearing Firestone described as a “radical feminist,” but her arguments — at least the ones quoted here — are certainly sensible and admirable.

I doubt we’ll ever get to a stage where “genital differences between human beings would no longer matter culturally,” but certainly we can make further strides in that worthy direction, and should.

And a hearty “hear! hear!” to the “central necessity of relieving women of asymmetrical duties in regard to childbirth and child-rearing.” Not only does this place an uneven burden upon the woman, significantly damage any career path, but allowing men to opt out of equal participation in child-rearing furthers this unfair condition, atrophies their nurturing capacities.

And makes them feel less important and valued as parents; that aside from being breadwinners, their contribution to parenting is negligible. (One unintended side-effect of unduly praising “single mothers” in attempts to overcome the stigma once placed on their condition; the male thinks if he’s so utterly unimportant to raising kids, what does it matter if he leaves? The kids won’t be any the worse off…)

Can’t see this catching on either, but “food for thought”:

———————–

Huichol Indians are descendants of the Aztecs, and live in the mountains of North Central Mexico. During traditional childbirth, the father sits above his labouring wife on the roof of their hut. Ropes are tied around his testicles and his wife holds onto the other ends. Each time she feels a painful contraction, she tugs on the ropes so that her husband will share some of the pain of their child’s entrance into the world.

————————

More details (and a hilarious Huichol “yarn painting” — almost a cartoon; the expression on the husband’s face is priceless — depicting the scene at http://www.museumofhoaxes.com/hoax/weblog/comments/4181/ .

(No, the practice is not a hoax, despite the site’s name.)

Hmm, this reminded me of 2 things:

1. I just happened to be reading Badiou’s Philosophy for Militants. He’s always a bizarre read, since it’s never readily apparent that anything is sinking in, only later, when I run across something like the above essay. Anyway, he suggests that equality is not about liberty, but about justice. He ties this into philosophy being a communist/democratic act, but one that shouldn’t relativize all opinions as equally true. Thus, everyone has the possibility of being philosophical, but not the freedom of taking anything as true. That brings me to:

2. Christian missionaries during colonial times were often the ones seeing colonized people as equally human, worthy of God’s love. Thus, the colonized were justly given some measure of equality, provided (and this is the key) they adopted the religious beliefs of the colonizers.

I don’t have a big bang conclusion to this, but Badiou is certainly an admirer of Paul, while the latter issue seems make this “equality” under the eyes of God (or philosophy) problematic.

Good essay, Bert.

Thanks Charles! And not a minor point, about the colonizers.

The issue of proselytizing is one I don’t have an answer for. The message of freedom as well of that of equality offered by Christianity is pretty much all predicated on accepting Jesus as Savior.

So my response is that no authority gets to speak for Jesus (God), but the idea that we are all free from suffering (without believing that we are) is also pretty specious. All earthly power is drenched in the blood others, rather than the blood of itself.

That doesn’t solve the problem, but it summarizes my thoughts.

“the bloof OF others,” that is. My blood bad.

Oh screw it.

Hopefully it was obvious that I was saying “oh screw it” about my endless typos.

Wanted to also mention, in regard to colonialism, that the history of secular classical ideologies, like those of the Roman Empire (in which Jesus and Paul were in marked opposition) are not immune from critique. All Western colonialism stems first and foremost from the serenely rational classical idealism of the Roman state, with Christianity cynically added on to give it some hypnotic bloodthirsty fanaticism. Christianity has not admirably unstuck itself from imperial ambitions, but the tradition (as could presumably be said of classicism, and its positivist offspring) holds plenty of ground for resistance.

Well, there’s also the Roman invention of imperialist hypocrisy: we’re bringing civilisation and the reign of peace to those lucky barbarians we’re massacring and looting. Christianity added another fillip to this rationalisation.

Yes, my point exactly. It would be worth articulating a Christian critique of colonialism, which would be neither Marxist nor liberal-multiculturalist. But basically maybe “stop coveting other people’s stuff, plus also don’t kill them,”

I think Yoder/Hauerwas do a pretty good job of articulating a non-imperial Christianity. An insistence that pacifism is the essence of Christianity makes it logically impossible to justify conquest in the name of Christ, I think.

It also makes it extremely hard to justify any collaboration or instrumentalization of the state for Christian goals.”Christian nation” becomes an oxymoron.

I approve of all of those ideas. Conscientious objectors in “just wars” (WW2 Allies, American Civil War Union)really mess up people’s ideas about Christianity, if they’re taken seriously.