In his 1996 study Manhood in America: A Cultural History, Michael Kimmel describes the invention of the cowboy, a “mythic creation” with origins in the novels of James Fenimore Cooper; this creature of the nineteenth century imagination, as Kimmel points out, “doesn’t really exist, except in the pages of the western, the literary genre heralded by the publication of Owen Wister’s novel The Virginian in 1902” (Kimmel 149—150). Kimmel describes the hero of the western as a character who is “fierce and brave,” a man “willing to venture into unknown territory” in order to

tame it for women, children, and emasculated civilized men. As soon as the environment has been subdued, he must move on, unconstrained by the demands of civilized life, unhampered by clinging women and whining children and uncaring bosses and managers. (149)

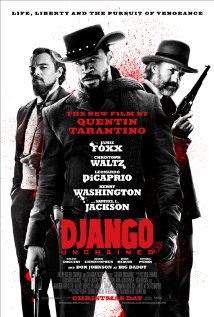

In The Virginian, and in the other novels, magazine serials, films, comic books, and television shows it inspired, this hero, of course, as Kimmel points out—a being who is “free in a free country, embodying republican virtue and autonomy”—“is white” (Kimmel 151). Quentin Tarantino’s new film Django Unchained, however, asks us to imagine a different sort of Western hero, one whose history returns us to the origins of African-American cinema.

Image from IMDB

Like Inglourious Basterds (2009), Tarantino’s new film is a vision of an alternate history. Jamie Foxx’s title character joins forces with Christoph Waltz’s German bounty hunter Dr. King Schultz on a series of adventures which culminate in the attempted rescue of Django’s wife Hildy (Kerry Washington). Unlike the characters Kimmel describes, Django is not running to the territory to escape the clutches of civilization. His journey is an inversion of the hero’s trajectory in the traditional western. At every step of the narrative, Django embraces civilization and demands the dignity which has been denied to him and his wife.

The fantasy of an escape into the wilderness, as Kimmel describes, was the invention of a writer from “an aristocratic Philadelphia family”; Owen Wister created a genre which “represented the apotheosis of masculinist fantasy, a revolt not against women but against feminization. The vast prairie is the domain of male liberation from workplace humiliation, cultural feminization, and domestic emasculation” (Kimmel 150). In Tarantino’s film, however, Django’s journey returns him to civilization, the violent, decadent world of Calvin Candie’s Mississippi plantation. It is not a feminized space which seeks to emasculate Django, but one of Candie’s henchmen, Billy Crash (Walton Goggins), in a hellish scene which alludes to the infamous torture sequence from Tarantino’s first film Reservoir Dogs (1992). This time the torture scene, stripped of the bloody glamour and outrageousness of Michael Madsen’s performance and the Dylanesque humor of “Stuck in the Middle with You,” is brutal and ferocious, a reminder to the audience of the horrific consequences of the plantation system for both the slavers and those who have been enslaved.

What animates the blood and the violence of this world? Greed drives Leonardo DiCaprio’s Calvin Candie and his loyal servant Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson). In a sly reference to Greed, Eric Von Stroheim’s 1924 silent adaptation of Frank Norris’s 1899 naturalist novel McTeague, Tarantino’s Dr. King Schultz masquerades as a dentist, his wagon crowned with an enormous molar dancing on the end of a spring. In the logic of the film, greed is not a simple desire for wealth and property but is a form of anxiety caused by a perceived loss of control: Calvin fears he is not as wise as his father; Stephen is afraid of the new world Django represents. Both Calvin and Stephen are terrified of the freedom which Jim Croce celebrates in “I Got a Name” (written by Norman Gimbel and Charles Fox), the 1973 hit which provides the soundtrack as Schultz and Django ride out the winter and collect the bounties which will enable them to return to Mississippi to rescue Hildy: “And I’m gonna go there free/Like the fool I am and I’ll always be/I’ve got a dream/I’ve got a dream/They can change their minds but they can’t change me.”

Django is not searching for freedom from the feminized spaces Kimmel describes. Instead, Django’s journey is one of return, of reclamation. He is a western hero who abandons the John Ford-like expanses of the territory, which, as figured by Tarantino, are a series of illusions: over the course of the film, sometimes within the same sequence, Django journeys from what appears to be the deserts of the southwest; to the Rocky Mountains; to the live oak trees and bayous of Louisiana; to the mud-clotted streets of a Jack London-like frontier town (with Tom Wopat, Luke Duke from The Dukes of Hazzard, as the Marshall); to the hills of Topanga Canyon, the backdrop of most of the westerns filmed for American television in the 1950s and 1960s.

In Tarantino’s imagined southern landscape, Mississippi is just miles away from the golden hills just outside Los Angeles, and those hills are filled with extras from the Australian outback. As Candie and Stephen employ every means of violence and torture at their disposal to protect Candyland, Django comes to understand that the stability of place is an illusion; what is real is the world which has been denied to him, the vision of his wife Hildy which repeatedly haunts him until he finds her again in Mississippi.

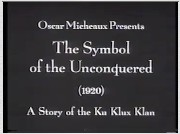

There is a long history of African-American westerns, dating back to the late teens and early 1920s. Like Django Unchained, these early films reverse the trajectory of Wister’s original myth, but movies like Oscar Micheaux’s 1920 The Symbol of the Unconquered should not be called revisionist westerns. Instead, both films, like their heroes, make demands on the genre itself: if the western is a form which celebrates freedom, Tarantino and Micheaux suggest, what better hero than an African-American fighting the evil embodied by the Ku Klux Klan? Pioneer African-American filmmaker Micheaux’s silent masterpiece, which was restored in the 1990s, can now be seen on YouTube with Max Roach’s masterful score (for more on the restoration of the film, see Jane M. Gaines’ Fire and Desire: Mixed-Race Movies in the Silent Era, page 331, and Pearl Bowser and Louise Spence’s Writing Himself into History: Oscar Micheaux, His Silent Films, and His Audiences).

Image from The Museum of African American Cinema

While Hugh Van Allen (Walker Thompson) is the hero of The Symbol of the Unconquered, Eve Mason, the heroine portrayed by the luminous Iris Hall, is the focus of most of Micheaux’s attention. Having inherited a plot of land from her grandfather, “an old negro prospector,” she “leaves Selma, Alabama, for the Northwest” in order to “locate the land.” When she arrives, she falls in love with Van Allen, a black homesteader whose property borders her grandfather’s land. The subtitle of the restored version of the film, “A Story of the Ku Klux Klan,” indicates the dangers Eve will face as The Knights of the Black Cross threaten Van Allen. When the film’s villain, Jefferson Driscoll (Lawrence Chenault), discovers that Van Allen’s property possesses tremendous oil reserves, he enlists Old Bill Stanton to drive the black homesteader away.

Warned of the impending danger, Eve promises, “I’ll ride to Oristown and bring back help.” A title card then asks us to imagine “The infernal ride” as Eve returns in what appears to be a rodeo costume. In her fringed buckskin jacket and white hat, she mounts a horse and rides in daylight, as Micheaux cuts to images of the hooded knights, riding in darkness, their torches blazing, their faces eerie and obscure. In the fragments of the film which are left to us, it is impossible to tell if they are pursuing her, or if they are gathering to torch Van Allen’s tent; the climax of the film in which, as the title card tells us, these midnight riders are “annihilated” is also missing, but the resolution of the story remains intact. Eve and Van Allen, now an oil baron, fall in love and, in the movie’s final scene, embrace.

The most powerful image of Micheaux’s film is not this final embrace but the shot of Eve Mason on her horse, riding furiously to Oristown to raise the alarm. Like Django’s journey, hers is a return, and her presence is a demand, not for control but for justice. While the white cowboy’s privilege lies in his ability to choose between a quiet life in civilization or an escape to the territory, Django and Eve exist in a world in which this choice has been denied to them. They must reclaim the ability to make this choice, and when they do so, both choose in favor of the domestic spaces which inspired them to take this “infernal ride” in the first place. Perhaps, then, we can read both Django Unchained and The Symbol of the Unconquered not as westerns but as comedies in the Shakespearean sense, in which the forces of evil are contained, and a world of chaos is redeemed as our heroes—and heroines—marry their beloveds and, like dime-novel cowboys, ride off into the sunset.

References

Django Unchained. Dir. Quentin Tarantino. Perf. Jamie Foxx, Christoph Waltz, Leonardo DiCaprio, Kerry Washington. The Weinstein Company, 2012. Film.

Gaines, Jane M. Fire and Desire: Mixed-Race Movies in the Silent Era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001. Print.

Kimmel, Michael. Manhood in America: A Cultural History. New York: The Free Press, 1996. Print.

The Symbol of the Unconquered. Dir. Oscar Micheaux. Perf. Iris Hall, Walker Thompson, Lawrence Chenault, Mattie Wilkes, E.G. Tatum. 1920. Film.

Nice review, Brian. Micheaux is always worth revisiting and rediscovering.

But if I may, let me put in a good word for Ford, Wister, and the the standard Hollywod western. I know that Kimmel’s vision of the genre holds a lot of sway in general, but his particular version of the the cultural history of the cowboy seems painfully thin. (Of course, this is a problem, I find, with pretty much all his pop-soc work on masculinity.)

I’ve no time for a full re-reading, but it may be worth nothing that even the Virginian returns “back home” — first out east and then back to Wyoming, where he finds his way into a happy family life and a secure position in the economy. Indeed, one of the last “riding into the sunset” moments we see is with the Virginian and his wife.

And, turning to Ford, one could say the same thing about the ending of a film like “Stagecoach.” At the end of that film, Ringo does “escape” from civilization, the law, and its corruptions. But he does so with his wife-to-be. (One of the greatest scenes in that film shows the two of them walking silently and solemnly down the street of Lordsburg, in a virtual wedding ceremony — which may also become a funeral.)

None of this has anything to do with your stylish reading of Django and the Unconquered. But those movies’ own peers and forebears are more varied and complex than one would first suspect. They all have a deep sense of home and how one gets there.

(This differs from J.F. Cooper, where the only thing Hawkeye and Chingachgook can do, as the novels ends, is die — much as Ethan Edwards is closed out of the house in the final shot of “The Searchers.”)

As a side note, take a look at Tarantino’s interview with H.L. Gates at “The Root,” where the director really takes Ford to task for his racism and “kept alive this idea of Anglo-Saxon humanity compared to everybody else’s humanity.”

Wow, great review.

As Candie and Stephen employ every means of violence and torture at their disposal to protect Candyland, Django comes to understand that the stability of place is an illusion; what is real is the world which has been denied to him, the vision of his wife Hildy which repeatedly haunts him until he finds her again in Mississippi.

I think you are right that Django understands the stability of Candyland to be an illusion, but not because his bond with Hilde is more real, but because of what Candi says at the dinner table: “Growing up surrounded by niggers, I always wondered – why don’t they kill us?”

Candi then goes into this whole thing about phrenology and black people being naturally more servile than white people, etc – he argues that the domination of white people over black people is natural – but the film contradicts that by showing the huge amounts of violence required to maintain it. It’s clear in Django that the reason black people accept the system – when they do accept it – is that it’s enforced by tremendous violence.

For the race slavery system to exist, there have to be laws about black people riding horses and entering saloons; black free men bounty hunters have to be punished for their presumption to shoot white people by morons in hoods; every attempt to speak with authority and dignity has to be met with physical violence except if you’re an unhinged loon like Candi and then you might tolerate or enjoy it selectively; runaways have to be severely beaten and then separated from their partners and then branded and then thrown in “hot boxes” and then turned into comfort women; and so on.

So yeah, the system is definitely fragile: if it wasn’t, the extreme violence with which every white American character responds to the idea that Django or another black character doesn’t except white superiority wouldn’t be necessary.

Which you said, in your review, haha. I guess the violence just seems like more an obvious point to me than the domestic. It’s the perfect subject for Tarratino: a place where no amount of violence can be more extreme than what actually happened, and every iota of violence by the hero can be justified.

What Ford is about is not the expansion of the territory. Ford is about the clash between myth and truth (Fort Apache, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance – his masterpiece in my humble opinion) among other things like the nostalgia provoked by loss (Young Mister Lincoln, The Searchers – an essay about racism). I should revisit Ford’s oeuvre though. I haven’t done so in a while.

Thanks for the thoughtful and thought-provoking responses, Peter, subdee, and Domingos (and happy new year!). I’m suddenly reminded of the references to Wister in Micheaux’s first autobiographical novel _The Conquest_. Here is a link:

http://books.google.com/books?id=A9CJ_dPnd18C&q=virginian#v=snippet&q=virginian&f=false

This passage is from an early sequence in the book in which the hero is working as a Pullman porter and describes what he sees as he ventures West; I’ve always thought Micheaux is at his best when he is describing these vistas:

“Nearing the Continental divide the car pulls into Rawlins, which is about the highest, driest and most uninviting place on the line. From here the stage lines radiate for a hundred miles to the north and south. Near here is Medicine Bow, where Owen Wister lays the beginning scenes of the ‘Virginian’; and beyond lies Rock Springs, the home of the famous coal that bears its name and which commands the highest price of any bituminous coal.” (43–44)

Micheaux’s relationship to the West was a complex one. His editorials for newspapers like the Chicago Defender urged other African Americans to join him as he tried to build a life near the Rosebud Reservation in southern South Dakota, but his reminiscences of his time near Gregory, Dallas, and Bonesteel are always fraught with regret and sadness. I suspect he also admired Wister as much as he did the other popular writers he alludes to in his early books, most of whom (like Maude Radford Warren) are long forgotten.

I also need to take a look at that interview with Gates!

subdee, your comments on Tarantino’s use of violence also have me thinking about how Micheaux employs violence in his sound films of the 1930s, the detective/gangster films like _Ten Minutes to Live_ and _Murder in Harlem, his take on the Leo Frank case. Given Micheaux’s pulp detective novels of the 1940s, it might be interesting to juxtapose Samuel Jackson’s character in _Pulp Fiction_ with some of Micheaux’s pulp heroes.

And, as you mentioned, Domingos, I should go back and watch _The Searchers_ or even _Cheyenne Autumn_, as I also haven’t seen them in years. I wonder what affinities those films would have with Django? (Though I have to admit that, in the middle of Django, I kept thinking of Clint Eastwood’s 1985 film _Pale Rider_, but perhaps that was some form of nostalgia of seeing it on WPIX on Saturday afternoons when I was a kid).

No problem! I was really impressed by Tarantino as well as by this post. Micheaux is new to me and very, very interesting.

Happy new year Brian!

There’s also Sergeant Rutledge, of course…

Unfortunately I can’t also forget the coon played by Step’n Fetchit in Steamboat ‘Round the Bend.

By the way, I haven’t seen Django Unchained yet, but I dislike Tarantino so much that I almost certainly will agree with Spike Lee when he says: “American Slavery Was Not A Sergio Leone Spaghetti Western. It Was A Holocaust. My Ancestors Are Slaves. Stolen From Africa. I Will Honor Them [by not watching Tarantino’s film].”

Django Unchained only pretends to be a Western, at its heart it’s an anti-slavery movie… the one way the movie could backfire is if the audience looks at the fantasy elements, and then concludes that the very real violence against black slaves and freemen is also a fantasy or exaggerated. If you know that it’s for real, the movie is very affecting and effective.

But then I skipped Inglorious Basterds for the same reason Spike Lee gives for skipping Django Unchained, so I have no room to talk.

Subdee, I think that’s a mistake. As a Jew, I adored Inglorious Basterds. The fantasy of Jews as sexy, authentic perpetrators of violence, rather than as pitiful victims to be saved by the white good guy, was pretty thoroughly satisfying/hysterical. More than that, though, it’s pretty clearly about Hollywood depictions of the Holocaust, and of the ridiculous/tragic/despicable difference between that and the actual Holocaust. I don’t know…like I said, I thought it was brilliant and mean and funny and joyful — not least because movies about the Holocaust aren’t supposed to be any of those things.

I’ve got to see Django Unchained, damn it….

Spike Lee’s a director I like a lot too…but I think he sometimes thinks with his mouth rather than his brain. Not that he should see the movie if he doesn’t want to, but I think his vendetta against Tarantino is seriously misguided. Not that Tarantino is perfect on racial issues or beyond criticism or anything — but compared to most Hollywood films? Please.

Yeah, after watching Django Unchained I’m feeling a lot more kindly disposed towards Inglorious Basterds. If it’s on TV or something I’ll probably watch it.

In Django, it’s not just violence per se that’s the subject, but depictions of violence, or filmic violence. Filmic violence can be funnier than real violence, but because it’s funny, it can also be more affecting – you remember the unpleasant things along with the funny things instead of throwing the whole movie out of your brain the second it’s over (because, no matter how much you want to be a Good and Serious person, it’s too upsetting to keep thinking about).

Plus I kind of like that the Nazi guy from Inglorious Basterds shows up in Django Unchained as the complex but basically good German bounty hunter.

You know, subdee, if you want to write about Django Unchained for us, feel free. I’d be into having a few takes on it, if folks were up for it.

I don’t think I have any more insight into this movie than a thousand other film geeks! What you want is for someone who’s a fan of the violent-revenge-film genre to write an article about Django exploring that side of the movie. I can ask my friend Sabina if she’d be interested.

Re black cowboys on the Old West, this 1993 story writes:

———————

…black cattlemen and gunslingers were a significant presence in the West. About 8,000 black cowboys rode the trails after the Civil War, says the historian William Loren Katz, author of “The Black West”; Oklahoma once was virtually an all-black territory.

Although Hollywood clings to an archetype of the cowboy as a blue-eyed defender of white civilization, at least six Western films over the next two years will challenge that image…

In “The Negro Cowboys,” one of the rare books documenting blacks in the West, Philip Durham and Everett Jones speculate that the absence of blacks in Western fiction and films had much to do with the “unique status of the cowboy as an American folk hero,” one with which white Protestant Americans must be able to identify. In other words, try to imagine a black John Wayne.

But black cowboys have appeared in films, and not always in marginal roles. Westerns were among the “race films” of the 1920s and 1930s that imitated the genres of white Hollywood for segregated audiences…

———————–

Emphasis added; more (including details about those “black Westerns”) at http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1993-06-17/features/9306170366_1_black-cowboys-black-directors-and-writers-black-western-history

———————–

Despite the risks, half a million black men, women and children moved to Texas and Oklahoma. They came to the Lone Star State because they enjoyed far more freedom than in other parts of the country. And black cowboys suffered from less discrimination than other occupations, said Kenneth W. Porter, author and buffalo soldier re-enactor. Five thousand black men helped drive cattle up the Chisholm Trail after the Civil War. Some had come West as slaves and were roping and branding cattle before they became free men. Others came after emancipation, looking for a free life where skill counted more than skin color. The usual trail crew of eight often included two black cowboys. On the cattle drive, these cowboys had to work harder and longer than anyone else to gain respect from the rest of the cowhands. Blacks were usually called upon to do bronco busting or wrangling, The horse wrangler had to prepare fresh horses for all the cowboys and find new grazing spots every evening.

Unlike most jobs for blacks outside Texas, cowboys were not discriminated against in wages. Likewise, black and white cowboys slept in the same shack or under the same blankets as other cowboys. Fights between black and white cowboys were rare. However, black cowboys suffered racism once they arrived in town. Bartenders made them sit at one end of the bar, they were not allowed to solicit white prostitutes, and whites called them derogatory names…

—————————

http://www.claycountyjailmuseum.org/Blackcowboys.html

This article also tells how American-Indian and Hispanic cowboys were a substantial presence in the Old West, deleted from most “Westerns”:

—————————

A significant number of African-American freedmen also were drawn to cowboy life, in part because there was not quite as much discrimination in the west as in other areas of American society at the time. A significant number of Mexicans and American Indians already living in the region also worked as cowboys. Later, particularly after 1890, when American policy promoted “assimilation” of Indian people, some Indian boarding schools also taught ranching skills. Today, some Native Americans in the western United States own cattle and small ranches, and many are still employed as cowboys, especially on ranches located near Indian Reservations. The “Indian Cowboy” also became a commonplace sight on the rodeo circuit.

Because cowboys ranked low in the social structure of the period, there are no firm figures on the actual proportion of various races. One writer states that cowboys were “… of two classes—those recruited from Texas and other States on the eastern slope; and Mexicans, from the south-western region…” Census records suggest that about 15% of all cowboys were of African-American ancestry—ranging from about 25% on the trail drives out of Texas, to very few in the northwest. Similarly, cowboys of Mexican descent also averaged about 15% of the total, but were more common in Texas and the southwest. Other estimates suggest that in the late 19th century, one out of every three cowboys was a Mexican vaquero, and 20% may have been African-American.

——————————

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cowboy

BTW, when casting “Django Unchained,” Tarantino was favorably impressed that Jamie Foxx — who’s from Texas — knew how to ride and had his own horse. (In fact, that’s the horse he rides in “Django.”)

——————————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

By the way, I haven’t seen Django Unchained yet, but I dislike Tarantino so much that…

——————————–

But, did you like “Jackie Brown”? (This excellent film, written about by Noah at http://www.theatlantic.com/sexes/archive/2012/12/the-one-time-quentin-tarantino-got-blaxploitation-masculinity-right/266469/ , has been described as “the film people who usually hate Quentin Tarantino…like.”)

To be honest I can’t remember a thing I saw in Jackie Brown.

Noah: “Spike Lee’s a director I like a lot too…but I think he sometimes thinks with his mouth rather than his brain. Not that he should see the movie if he doesn’t want to, but I think his vendetta against Tarantino is seriously misguided. Not that Tarantino is perfect on racial issues or beyond criticism or anything — but compared to most Hollywood films? Please.”

Are you saying that people who dislike pulp don’t think with their brains? And why should Spike Lee compare Tarantino with those who are worst than he is instead of comparing him with those who are better?

Maybe ’cause he was such a good actor, or a nod to Karl May?

————————

Karl Friedrich May…was a popular German writer, noted mainly for adventure novels set in the American Old West (best known for…the characters of Winnetou, the wise chief of the Apache Tribe, and Old Shatterhand, the author’s alter ego and Winnetou’s white blood brother.

May’s heroes are often described as being of German ancestry. In addition, following the Romantic ideal of the “noble savage” and inspired by the writings of writers like James Fenimore Cooper or George Catlin, his Native Americans are usually portrayed as innocent victims of white law-breakers, and many are presented as heroic characters.

————————

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_May

————————-

Karl May (1842 – 1912) is the bestselling German writer of all time, chiefly noted for his western books set in America’s Old West and similar books set in the Middle East. …Since their publication, more than 200 million copies of Karl May’s 70 books have been sold worldwide, and his works have been translated into over 40 languages.

—————————

http://www.karlmayusa.com/Books%20&%20Related.htm

Christoph Waltz is a great actor.

What I can’t understand is why the notion of fun violence (which is Hollywood pulp violence, of course) being offensive to the real victims is such a difficult idea to grasp.

Domingos, I don’t think the issue with Lee is dislike of pulp. His own films are hardly free of pulp (they often seem to end with the guns coming out, for example) Anyway, if he disliked pulp, like I said, he’d have lots and lots of things to complain about. He singles out Tarantino specifically on the grounds that his treatment of race is uniquely bad in popular cinema. I don’t see it. I mean, Lee isn’t saying, “this is crap compared to Tarkovsky.” He’s saying, “this is racist popular culture, which must be denounced.”

Spike Lee’s public comments just tend to be a lot less thoughtful than his films. Or so it seems to me, anyway.

The problem is that sententious seriousness is not necessarily an improvement.

Any representation is not going to be real. Tarantino is always pretty much interested in showing the distance between representation and reality (certainly in Basterds, where it’s deliberately and flagrantly not historically accurate.) Again, as someone whose ethnicity is the one being discussed, I find Basterds a lot less offensive than Schindler’s List…or than Maus, for that matter.

Not so say all Jews would feel that way, or that all people should feel that way or anything…I’m just saying there are other possible ways to look at this issue.

I mean, I haven’t seen Lincoln, but I really find it hard to believe that a Spielberg film is devoid of Hollywood schmaltz and pulp genre markers. But Lee’s not out in public talking about how evil that is, I don’t think. I just feel like in his case the denunciation of pulp is not especially consistent.

Well, let me quote Spike Lee again: “American slavery was not a Sergio Leone spaghetti Western.” How can such a clear statement be misread?

Because of this thread I watched Stagecoach again. Re. black cowboys, I was surprised to see that Woody Strode has a small appearance. Why is he talking bad Spanish is a mystery though…

By the way, the problem with Spielberg’s films is not his approach. The problem is Spielberg himself… I find it funny that you can accuse him of “sententious seriousness” and of being full of “Hollywood schmaltz and pulp genre markers” at the same time. Everything is fair to defend Saint Tarantino, I guess…

You guys should watch the movie, the violence against the slaves isn’t “fun” pulpy adventure, it’s dull and gruesome and horrible.

For instance, the white plantation owner, Candi, has his slaves fight each other for sport. They are rolling around on the floor, trying to bash each other’s heads in. This goes on for a while and the only score (iirc) is the sound of flesh hitting flesh. The contrast between Candi’s joviality, the suppressed hatred and disgust of his other (house) slaves who are present, and the badly-suppressed nausea of the German bounty hunter – who had previously blown away a father in front of his son – drives home the system’s inhumanity and cruelty.

And it’s not only Candi who supports this inhuman violence and cruelty, although he is one with the most power to indulge in pure sadism. Every white American character is implicated. They all react violently to any challenge to the system of white superiority – or if they don’t act, you can tell they would like to.

I can understand being against any film dedicated to the onscreen portrayal of frank and brutal violence against black Americans. There will always be some sickos in the audience who enjoy it. I can also understand being uneasy, as a black American, with a film by a white filmmaker that delights in and celebrates a single black man’s violent retaliation against this violent system. Are the white people in the audience going to reflexively identify with the white Southerners on screen and look at me funny as we exit the theater, wondering if I am going to murder them in their own homes?

Furthermore, is Taratino calling out the slaves who didn’t rebel, or who rebelled in more subtle ways? I think he sidesteps this issue pretty neatly by positing Django as a larger-than-life folk hero, showing how all-encompassing the system is, having lots of closeups on contemptuous faces when Django is pretending to be a black slaver, talking repeatedly about runaways, etc. Comparing this to Holocaust films, it’s closer to Transport from Paradise – showing the heroic resistance of the Jews, condemning collaborators – than something like We Have to Help Each Other where the focus is on the reluctant heroism of the sheltering Gentile family.

Anyway, here is an interview with Taratino where he discusses his own uneasiness about the movie. It’s not free of problems, but it’s not a simple spaghetti Western either.

Oh please; I happen to like Tarantino a lot. That doesn’t mean he’s beyond criticism. I thought the Kill Bill films were pretty mediocre, fwiw.

Sententious seriousness is in no ways opposed to schmaltz or pulp genre markers. I mean, you saw Schindler’s List, right?

And I didn’t misread Spike Lee. I just feel that he’s applying his dislike of pulp selectively.

Also…I’m pretty sure Tarantino is very aware that slavery is not a spaghetti western. Is it a serious aesthetic endeavor instead? Or, you know, is it possible that acknowledging the distance of one’s representation from reality might be worthwhile?

I haven’t seen the film, and it’s possible that Tarantino handles this poorly. But Lee hasn’t seen the film either. The idea that pulp genre markers can never be used in intelligent ways is something I don’t even think you agree with. Certainly, given his films, Lee doesn’t think that.

We Have to Help Each Other is called Divided We Fall in English. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0234288/

Transport from Paradise is a famous movie. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0056609/

Spike Lee is a humorless asshole who makes mostly simplistic, didactic movies. Do the Right Thing is okay, but that was a long time ago. The idea that one might use films to encourage multiple interpretations, rather than spoonfeeding the audience, is a foreign aesthetic to him. DU is a far more interesting and honest examination of black history than Malcolm X for whatever that’s worth (not much, I’d say). Tarantino’s color is Lee’s main problem.

The violence against (SPOILERS):

a) slavers – by another white man;

a) white criminals (stagecoach robbers) in the Wild West – by a white man and a black man working together;

b) white criminals who have escaped to Tennessee where they work as overseers on a plantation – by a black man;

c) white criminals who have retired from being criminals – by a white man;

d) the sadistic owner of a large plantation – by a white man;

e) all the men who support the plantation owner with their rifles kept ever at the ready – by a black man;

f) the plantation owner’s sister – by a black man;

g) more slavers – by a black man;

h) all the men who support the plantation in secondary roles – by a black man;

i) the collaborating black slaves – by a black man

Is pretty pulpy though. Tarantino invites us to enjoy this violence. As you can see, there’s a not-so-subtle escalation of targets which is designed to keep the audience on Django’s side until the very end, when we should cheer as he and Hilde ride off into the sunset.

Noah: “And I didn’t misread Spike Lee. I just feel that he’s applying his dislike of pulp selectively.”

Of course he is. He’s disliking it this time when slavery is in the middle of the whole mess. If he’s contradicting himself (namely when he uses pulp violence himself to entertain the audience) it doesn’t mean that he’s not right, or does it?

Thanks subdee: the above doesn’t look good at all…

Nah, Spike Lee’s better than that. Bamboozled is a mess, but an interesting mess, which certainly leaves open the possibility of multiple interpretations.

I think Lee’s just a better filmmaker than a critic. I think he dislikes Tarantino’s films because Tarantino actually cares about these issues. Most mainstream filmmakers are just casually stupid about race, and so they get ignored for the most part. Tarantino actually engages with the issue — which makes folks uncomfortable.

Domingos; I’m not saying he’s hypocritical necessarily, or even that he’s not right (the film could suck, for all I know.) But I think his framing, and his rationale, are pretty simplistic. Moreso than his films, I’d argue.

Which above, the above where the audience is invited to enjoy the revenge arc of a black ex-slave who has had everything taken away from him and could have it all taken away again at any time, or the above about how Tarantino does not apply his pulp smarts to the terrible violence against black slaves, but saves it for violence against white Americans implicated in the system of slavery in a bid to keep the audience on the side of the black hero?

Personally, my view is that Quentin Tarantino has finally found a subject so evil that every second of lovingly rendered filmic violence is justified.

I would say, all of the above.

And I say that as someone who avoids most movies that center around lovingly rendered filmic violence. It’s not really my bag.

Tarantino’s almost always really smart about violence; he very much treats it as a trope to be investigated, rather than (or sometimes in addition to) as a pleasure in itself.

The violence in Jackie Brown, for example, is almost always deflating and stupid, undermining the blaxploitation cool that it’s in theory supposed to be propping up. I talk about that here, in case anyone’s interested….

Well, fair enough, unlike in Spielberg’s Lincoln the morality of Taratino’s Django is very clear. Slavery = evil. Heroes = complex and not entirely wholesome people we support because they are the right people for the job at hand. To make these points, Taratino uses at a lot of filmmaker’s tricks, but he also makes it very clear and obvious that this is what he’s doing.

Temperamentally I’m more drawn to stories where good and evil aren’t so clear-cut and the solution isn’t wholesale murder, but desperate times etc, plus it’s good to see a movie like this that has progressive politics, for once.

Just don’t use my comments as an excuse to not see the movie, that’s all I’m asking.

I mean, I do think it’s fine to just say, I don’t ever like pulp violence, it’s always bad, no matter what’s done with it. I don’t agree with that, but I get where it’s coming from. But I think Tarantino often gets singled out as being particularly violent or outrageous or worthy of condemnation, and I don’t buy that. In general, I think his movies make people uncomfortable with violence not because they’re more violent than anything else out there (which they really aren’t) but because he actually presents violence as uncomfortable.

Oh, I’m definitely going to suffer through it.

It’s interesting how the second degree reading excuses everything. You sound like Jeet defending Crumb, Noah…

The payoff moment is far from uncomfortable.

Crumb’s an interesting counter-example. Racists aren’t rallying around Tarantino’s film, from what I can tell. On the contrary, it has seriously freaked the right out.

And I mean…you really think Jackie Brown uses invidious racist stereotypes the way Crumb does? You don’t see any space between Pam Grier’s portrayal and Angelfood McSpade? The attitude and approach are really, really different, I think. Crumb relies on exaggeration to distance himself from the racism, which I think is really ineffective. Tarantino relies on undermining tropes (most often by understatement rather than by overstatement) and on what seems to me to be quite thoughtful naturalistic characterization.

Again, if your point is, “they are both pulpy” — I can’t argue with that. But if you’re willing to get even slightly more nuanced than that, they don’t look very much alike. At least not to me.

Oh…and if you see it and want to write about it here, Domingos, that’d be great. I’m hoping for an impromptu round-table…already got at least one more essay lined up….

No, you’re right, it’s just that I don’t think Tarantino undermines anything either. As i said to Mike I don’t remember anything at all from Jackie Brown. In Django Unchained he seems to have used what I may call the Wonder Woman approach or, as I called it, the anti-matter approach: you turn white to black, but all the mediocre tropes (Manicheism, simplistic views, etc…) remain in their rightful places.

The Wonder Woman approach? The Wonder Woman approach?!

Sacrilege!

He he, yup… Marston did it first.

Tarantino or Lee have yet to direct a film I’ve liked, so Lee’s comments about “Django Unchained” have zero impact on me.

Saaaaaay… ol’ Spike should be a columnist here, since he panned a movie he not only hasn’t seen, but said he’ll never see!

Good point, but Tarantino is so predictable that you don’t need to be a Nostradamus exactly to guess what he’s up to every time.

I just want to point out that I made Domingos giggle. I think that means I win the thread.

———————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

To be honest I can’t remember a thing I saw in Jackie Brown.

———————

For that matter, I don’t remember much of it either, just impressions: Robert Forster was a honorable character, Pam Greer’s character was intelligent, resourceful. In view of the source, an Elmore Leonard novel, it’s no surprise I also recall it favorably (if not memorably) as a well-done crime caper story.

———————

While adapting [Elmore’s] Rum Punch into a screenplay, Tarantino changed the race of the main character from white to black, as well as renaming her from Burke to Brown, titling the screenplay Jackie Brown…Tarantino hesitated to discuss the changes with Leonard, finally speaking with Leonard as the film was about to start shooting.

Leonard loved the screenplay, considering it not only the best of the twenty-six screen adaptations of his novels and short stories, but also stating that it was possibly the best screenplay he had ever read.

Tarantino’s screenplay otherwise closely followed Leonard’s novel…

———————-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jackie_Brown_%28film%29

Hmmm! About time for a second viewing. Should see if the library has the video…

Oh, and I just scrolled down farther and noticed the Wiki entry above goes on to mention:

———————-

The film helped revive the careers of Grier and Forster, who received critical acclaim for their performances, as did Samuel L. Jackson.

Spike Lee criticized the film for its use of the word “nigger”, which is used 38 times in the film, stating “I’m not against the word, and I use it, but not excessively. And some people speak that way. But Quentin is infatuated with that word. What does he want to be made–an honorary Black man?” Jackson responded to Lee’s criticisms by saying that the word’s use was not offensive in the context of the film, and noting that Lee has used the word in many of his films. Tarantino also felt the word’s use was appropriate within the context of the film, and noted that it was used in Rum Punch, the novel the film was based upon. Jackson stated, “This film is a wonderful homage to Black exploitation films. This is a good film. And Spike hasn’t made one of those in a few years.”

———————-

Ouch!

———————-

subdee says:

Which above, the above where the audience is invited to enjoy the revenge arc of a black ex-slave who has had everything taken away from him and could have it all taken away again at any time, or the above about how Tarantino does not apply his pulp smarts to the terrible violence against black slaves, but saves it for violence against white Americans implicated in the system of slavery in a bid to keep the audience on the side of the black hero?

Personally, my view is that Quentin Tarantino has finally found a subject so evil that every second of lovingly rendered filmic violence is justified.

————————

Indeed so! I’m old enough to remember when the miniseries of “Roots” was first broadcast in ’77. The nationwide reaction among the Caucasian masses was, “Oooh, we had no idea slavery was so bad!”

It’s very telling how, as described here, Tarantino shows the violence against black slaves in an ugly, “uncool” fashion, thus explicitly making it repellent, to be condemned.

————————-

…unlike in Spielberg’s Lincoln the morality of Taratino’s Django is very clear. Slavery = evil. Heroes = complex and not entirely wholesome people we support because they are the right people for the job at hand.

————————–

One need not tear down “Lincoln” in order to praise “Django”; Spielberg and Tony Kushner’s film shows that president as very much a politician. When asked some tough questions by some black Federal soldiers at the start of the film, he is evasive or nonresponsive. In order to get through the slavery-abolishing Thirteenth Amendment, he is willing to connive, bribe en masse. He pushes through actions which he concedes might well be illegal, and waits for the voters to kick him out of office to see if they’re not.

In other words, Lincoln is shown as one of those “complex and not entirely wholesome people we support because they are the right people for the job at hand.”

Domingos, I suppose we’d have to really argue about the simplicity of views in Tarantino’s films, but Manicheism is most certainly not one of them. The plot of Inglourious Basterds, for example, is resolved by relying on help from the main Nazi villain in the film. The main villain in DU is a black slave.

Noah,

Bamboozled beats you in the face with it’s messages. It’s supposed to be funny, I think, but Lee doesn’t have it in him. True, you can still find conflicting readings from it, but that’s not really due to Lee. He’s a pretty terrible filmmaker who covers some subjects that deserved to be covered by others.

It’s been a long time since I saw Bamboozled, and I kind of hated the ending…but a lot of it is really extremely funny, I thought, and it really does have a complicated take on blackface iconography — both condemning it and acknowledging the role of blacks in blackface performance.

Lee is often quite funny — Do The Right Thing certainly was. He’s a very consciously political filmmaker, and I think his enjoyment of drama and loudness and pulp can sometimes make people miss the fact that there really are subtleties in his work. Not unlike Tarantino.

“Do the Right Thing” was probably Lee’s best film.

But that was 20-freakin’ years ago! Talk about resting on one’s laurels…

Since then, Lee is probably best known for giving opponents of the New York Knicks a hard time from his front row seat at the Garden… and panning Tarantino films!

If Lee were a musical group, I’d name him “The Coasters.”

Charles: “Domingos, I suppose we’d have to really argue about the simplicity of views in Tarantino’s films, but Manicheism is most certainly not one of them. The plot of Inglourious Basterds, for example, is resolved by relying on help from the main Nazi villain in the film. The main villain in DU is a black slave.”

The simple fact that you used the word “villain” implies Manicheism; skin color or political views notwithstanding.

I just watched Judge Priest by John Ford. Will Rogers surely builds a great character, but I almost threw up watching the damn thing!… The lyrics sang by Hattie McDaniel (who plays a mammie) and the Brown sisters are unbelievably racist. Add to that the already mentioned coon played by Stepin Fetchit.

There aren’t any villains in Reservoir Dogs, or Pulp Fiction, or Jackie Brown though. There are antagonists, but you tend to sympathize with everyone. (You do root for Jackie Brown in Jackie Brown, but Samuel Jackson’s character is very sympathetic to, as is DeNiro’s — and Brown’s ethics are questionable enough that you never actually see her as on the side of good. She’s mostly out for herself.)

Some of his other films have more definite heroes and villains…but it’s always pretty grey. I don’t know that we’re supposed to think Uma Thurman is a hero exactly, even if we’re rooting for her.

I would say the hillbillies in Pulp Fiction qualified as villains, and they’re the only reason the viewer wouldn’t see the Ving Rhames character that way. He’s the villain in the Willis story until they show up.

The Samuel L. Jackson character in Jackie Brown is pretty monstrous. Jackson’s a compelling actor, but that’s not the same thing as the character being sympathetic. I can’t imagine anyone feeling sad about the way he ends up. Relieved is probably more like it.

For you people looking for comics related material in the media a Yellow Kid page is shown at the beginning of Judge Priest. This is interesting because Ford wanted to plant the film in the 1890s so, he guessed that the viewers would associate the Yellow Kid with that era. But that’s me guessing too…

Hmmm…I’d forgotten the hillbillies (probably deliberately.) Still, there are certainly lots of characters who aren’t really heroes or villains (Travolta and Jackson aren’t either, really.)

Jackson in Jackie Brown is a monster — but he’s also funny and vulnerable and more than a little ridiculous. I think he’s sympathetic…which doesn’t mean you’re rooting for him. But it doesn’t exactly mean he’s the villain either. It’s not a good guy/bad guy film really.

With most crime fiction, the difference between the good guys and bad guys is usually a question of degree, not kind. They’re all corrupt. The good guys just have some redeeming qualities. It’s a genre convention, not a tendency peculiar to Tarantino.

What vulnerability did you see with the Jackson character in JB?

Well, we could argue that one way or another, but the point remains that we’re not really talking about Machiavellian in that case; there aren’t good guys and bad guys, there are just people you identify with more or less.

You could click through to the Atlantic article or a fuller version; but basically I see the Jackson character as a critique and/or mockery of hyperbolic blaxploitation masculinity. He’s just incredibly ineffective and ridiculous all the way through. The only people he kills are his employees, and only by being just pitifully dishonorable; every time he goes up against JB she emasculates him, literally or figuratively.

And then there’s that hysterical scene with Max where he says he doesn’t have the money to bail out Jackie, and starts trying to appeal to white guilt, and Max calls him on it, and Jackson has to pull out the money which he had on him all along. And there’s the scene with DeNiro where he kills him, “What happened to you, man? You used to be beautiful.” That’s a sad line for Jackson as well as for DeNiro, surely. And there are several sweet scenes where he’s joshing with DeNiro..and on and on. He’s just not Darth Vader, or even Marlo Stanfield. He’s a blundering bag of hapless bluster — which makes him charming and appealing, even though he’s still a murderous thug.

Oh, Domingos, hero/villain, protagonist/antagonist. Structural roles. If the hero is seen as complicit with the villain, then it’s not black and white. And, what, there’s no bad guys in your world, no one who performs immoral acts you object to? What a utopian you are. It seems kind of screwy not to see Nazism as bad, and the guys who practiced it as bad guys, but if you want to relativize their actions to where it was good within their culture, I guess that’s an approach … a bad approach, but an approach.

To quote Octave in The Rules of the Game: “What’s more terrifying in this world is that everyone has their reasons.” What I ask a writer is to be fair to her/his characters, nothing else. Those who don’t do that draw caricatures, nothing else.

That’s reasonable enough. To make sure I understand correctly, you wish that creators would show that even villainou… oops, “oppositional” characters have their particular set of motivations, reasons for what to others appear as monstrous actions?

It’s certainly lazy and simplistic when many (in reality as well as crafting fiction) take the shortcut of seeing others as simply “evil,” their actions without motive beyond doing evil for its own sake.

However, there are other factors that may be involved:

If a character is an officer in the Nazi military, does the creator need to have the character expound on Germany’s humiliations and economic travails after losing the Great War, or how he’s personally not crazy about the Nazis, but is driven by love of the Fatherland to fight for the Third Reich?

Should that guy who held up Bruce Wayne’s parents need to explain before shooting them he grew up in a series of abusive foster homes, with no positive role-models, is trying to get some cash to help his pregnant girlfriend?

For that matter, do we need to hear the “reasons” and stories of all those chaps in the Death Star, from Grand Moff Tarkin to the guys running the snack bar?

Because a creator doesn’t clearly show every character’s motivations, delve into the background that drove them to act thus, does not automatically mean they then go to the opposite extreme of rendering them as “caricatures, nothing else.” With all the condemnations flung about of “manicheanism,” this certainly is a simplistic all-or-nothing duality.

Moreover, this utterly fails to take into account the “structural roles” Charles mentioned, and that certain types of narrative require a momentum, endeavor to create an emotional effect, that delving into the backstory of every character would kill.

To charges of “manicheanism,” one could respond with “ivory tower-ism”; an attitude which refuses to consider creators’ working realities, that certain types of tales would be hamstrung by going into the “particular set of motivations, reasons for what to others appear as monstrous actions” of every character.

Domingos, Tarantino does that, though. All his characters have reasons in Jackie Brown, certainly…and in most of his other films too, with a couple of exceptions (the hillbillies in Pulp Fiction are unfortunate, I’ll admit.)

Mr. Blonde could be seen as the villain of Reservoir Dogs. Sure, he’s kind of charming, but between his offscreen massacre of innocent bystanders, his antagonism of the “good” characters (“You gonna bark all day, little doggie, or are you gonna bite?”), and his torture of the prisoner, he’s ultimately pretty horrifying, a force of “evil” even in the morally compromised world of the film.

On the other hand, there’s Kill Bill, which might be the most pulpy of all Tarantino’s films, and most all the “villains” in that movie (maybe Darryl Hannah’s character is an exception?) end up being sympathetic, likeable, or fleshed out enough that they become rounded an interesting in their roles as antagonists. Lucy Liu is an orphan brought up in a violent world and struggling to gain acceptance as a leader as a woman in a male-dominated criminal underground. Vivica Fox is a mother, having achieved the dream Uma Thurman was hoping for by leaving the life of crime behind for a comfortable domestic existence. Michael Madsen is a broken-down schlub who regrets his misdeeds and has to hock his Hattori Hanzo sword to hold on to his pitiful trailer. And Bill, the ultimate villain, turns out to be the utterly charming David Carradine, a loving, caring father who seems like he would be happy to reunite with the Bride and live happily ever after.

And Uma, on the other hand, who is the nominal hero of the piece, ends up murdering all of these people pretty horribly. She achieves her revenge, and even recovers the daughter she thought she had lost, but how much slaughter did she have to go through to do so? She ruined one young girl’s life, and upended her own daughter’s, and she dismembered another woman just for being one of Bill’s accomplices. As much as one wants to justify her actions, since that’s what the genre requires, the film does make you question the value of her revenge. It’s a fun ride, stylish as all hell, but Tarantino isn’t interested in just the surface; he builds a lot of genre inquiry and deconstruction into his films, and gives you a lot to think about if you want to. That’s why I dig him so much.

Oh, and I loved Django Unchained too; I’ll see if I can throw together something for HU, if you’re doing a roundtable.

Yes, Jean Renoir, the man who made WW1 look like a good time.

I think one thing Tarantino does exceptionally well is suggest a story behind most of his characters. He’s much more like classic Hollywood in that regard, where bit parts are often the most interesting in his movies. DU is something of a failure in this regard with a lot of bit parts being pretty lifeless.

Also, I agree about the hillbilly scene. It’s one of the weakest in Tarantino’s oeuvre. Not as bad as the proto-klan rally in the new one, though. That plays like a bad SNL skit.

“He’s a pretty terrible filmmaker who covers some subjects that deserved to be covered by others”

He can be a very good filmmaker when he feels up to it. His New Orleans doc “When the Levees Broke” is fine. But yeah, a lot of time he’s so slipshod in his writing that he comes off as a hack. “She Hate Me” and “Jungle Fever” are good examples of that. Unfortunately, he just doesn’t rise to the occasion that often.

Charles: “Yes, Jean Renoir, the man who made WW1 look like a good time.”

If you mean The Great Illusion that’s only true if you think that the decadence of a whole class is a good time to the members of said class. By the way, one of the most sympathetic characters in the film was a Jew. Which wasn’t a small thing in 1937.

Matt, I’d love you to do a piece. That’d be great.

I think that hillbilly scene is probably my least favorite thing in all of Tarantino. That Bruce Willis section of Pulp Fiction is in general pretty mediocre, is the truth.

Charles…is the Klan rally as bad as the Klan rally in O Brother Where Art Thou? Because that was pretty bad….

About that great film:

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/13/movies/renoirs-vision-for-a-united-europe-in-grand-illusion.html?_r=0

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Grande_Illusion

And, from the sublime to…

in the downloadable PDF of “Spike Lee’s Phantasmagoric Fantasy and the Black Female,” we read:

————————–

…a close friend of mine, who is an African American male filmmaker and a fan of Lee’s canon of work, insisted I rent She Hate Me. He did so with the promise that it was Lee’s best work to date, and that it would put to rest our many debates concerning Lee’s filmic misogyny.

Therefore, I watched the entire 138 minutes of this so-called feminist corrective. Not to my surprise, She Hate Me is similar to Lee’s previous films, insofar as a main component of the film is to reveal the plight of a Black male protagonist and to present Black women as co-conspirators in Black male subjugation. In this film, he does not use “Black female humiliation as plot resolution,” as cultural and feminist critic Michele Wallace writes about many of his previous films. Instead, Lee has given us a new bag of misogynistic and phallocentric tricks: Black women in this film humiliate Black men sexually by using one particular Black man as a breeder for hordes of baby-obsessed Black lesbians, thereby ruining the infrastructure of the nuclear, Black family.

————————–

Domingos,

If I were to rank the horrors in popular portrayals of war, Grand Illusion would be a lot closer to Hogan’s Heroes than Inglourious Basterds would. I just can’t see a guy who loves Renoir and Ford really having a moral problem with Tarantino. (Ford certainly made a better looking Western.)

Noah,

Hmm, I think that scene is really beautiful, so I prefer it. If you mean morally problematic, then you’d probably find more to object to in the Coens’ film, which I can understand. Tarantino paints the proto-klan as a bunch of silly dumbasses (one of them being Tarantino himself and another being Jonah Hill — can’t convey silly dumbasses better than that, I suppose). He was obviously influenced by Mel Brooks here.

Thanks for the New York Times link, Mike. A. O. Scott wrote: “The measure of Renoir’s generous spirit is that Rauffenstein and Boeldieu are also spared caricature. Renoir would hardly have forced von Stroheim, a director he revered, to play a cartoonish Prussian villain, and the script, by Renoir and Charles Spaak, takes pains to emphasize the tragic aspect of Rauffenstein’s situation.”

My point exactly.

I remember liking the last segment of Inglorious Basterds, but not much else. I don’t remember much of what I saw in the Tarantino’s films that I watched, as I said already. He’s not a director that interests me, at all…

Grand Illusion is a lot more than a war film. I’m not implying that a war film can’t be a great film; I’m just saying that a war film can be a lot more than a film about the horrors of war.

————————-

Charles Reece says:

…If I were to rank the horrors in popular portrayals of war, Grand Illusion would be a lot closer to Hogan’s Heroes than Inglourious Basterds would.

————————-

Sure; as mentioned at the earlier linked-to article (for those unacquainted with the film), it’s a comedy, featuring prisoners of war and their keeper.

————————-

…Jean Renoir’s great and piercing antiwar comedy.

…In the midst of a catastrophic war, far from the nightmare of the trenches, the gas and what seemed like the collective suicide of a civilization, they live in a peaceful microcosm of Europe.

————————–

Emphasis added; from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/13/movies/renoirs-vision-for-a-united-europe-in-grand-illusion.html?_r=0

If that makes any sense, that is…

I meant me, not Mike!…

If the following is what you were wondering “makes sense,” of course it does…

—————————

Domingos Isabelinho says:

Grand Illusion is a lot more than a war film. I’m not implying that a war film can’t be a great film; I’m just saying that a war film can be a lot more than a film about the horrors of war.

—————————-

Very much so.

Is not “Dr. Strangelove” something of a war film, which ends with the nuclear annihilation of the human race? Yet its subject is human folly, stupidity, self-delusion.

Kon Ichikawa’s “The Burmese Harp”: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Burmese_Harp_%281956_film%29 .

“The Men” dealt with “the travails of wartime paraplegics”; the physical and psychological trauma that was the aftereffect of war: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0042727/reviews , http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Men_%28film%29

Considering that “The Bridge on the River Kwai” was based on a novel by Pierre Boulle, author of “Planet of the Apes” and the blackly satiric “Face of a Hero” (AKA “Saving Face”; https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/pierre-boulle-2/face-of-a-hero-2/#review ), where bitter role-reversals abound, it’s no surprise that the warped thinking that humans are capable of is highlighted here. The setting is a P.O.W. camp, but human folly rather than the horrors of war is the subject:

—————————

Against the protests of some of his officers, [Lt. Colonel Nicholson] orders Captain Reeves…and Major Hughes…to design and build a proper bridge, despite its military value to the Japanese, for the sake of his men’s morale. The Japanese engineers had chosen a poor site, so the original construction is abandoned and a new bridge is begun 400 yards downstream…

—————————–

Emphasis added; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Bridge_on_the_River_Kwai

Charles, I should maybe see O Brother again. It’s hard for me to get past using Ralph Stanley as a Klan member; that really sticks in my craw. That is an amazing song though.

Mike’s reference to The Bridge On the River Kwai reminded me of one of my favorite books about the war: To the Kwai – and Back by Ronald Searle.

Here’s what Ronald Searle had to say about the film: “As for “The Bridge on the River Kwai”, it crossed the river only in the imagination of its author; his idea of British behaviour under the Japanese was equally bizarre.”

I recall reading an interview with the late Ralph Stanley in which he was asked how he felt about that Klan scene in O Brother. His reply was something along the lines of, “It’s just a movie. It ain’t real.”

Noah: “Spike Lee’s public comments just tend to be a lot less thoughtful than his films. Or so it seems to me, anyway.”

He has that in common with Tarantino! Anyone else hear that unbearable Fresh Air interview?

Just because Ralph Stanley is an extremely gracious individual is no reason not to kick the Coen brothers.

Everybody sounds unbearable on Fresh Air, don’t they?

Noah,

I was thinking of this scene, which didn’t feature any Stanley song. It’s been awhile since I’ve seen the film, too. I’m not sure what combination of the Klan and Stanley you’re talking about. Anyway, I can understand someone having a problem with making a Klan rally a beautiful spectacle. (Don’t agree that it’s a problem for the film, but I get it.)

I really love Fresh Air. I’m not afraid to admit it. The Waltz interview was great.

I’ve got that! Indeed, a splendid work. To those who know Searle only from his humorous illustrations, it shows what a superb and sensitive draftsman he could be: http://www.japansociety.org.uk/2525/to-the-kwai-and-back-war-drawings-1939-1945/ .

And…

A variety of Searle’s output, including “serious” story and advertising illustrations, at http://ecc-cartoonbooksclub.blogspot.com/2012/01/ronald-searle-great-part-1.html …

An interesting and substantial criticism of the premises behind “Django” at http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/culture/2013/01/how-accurate-is-quentin-tarantinos-portrayal-of-slavery-in-django-unchained.html …

I wrote a clerihew about Fresh Air once.

A crocodile swallowed Ms. Terri Gross

Then became lachrymose.

This left one last unanswered question:

Is it inner life or indigestion?

Anyway…having seen the Django, I actually quite enjoyed the Klan scene. It’s an Airplane moment for sure…but I love Airplane.