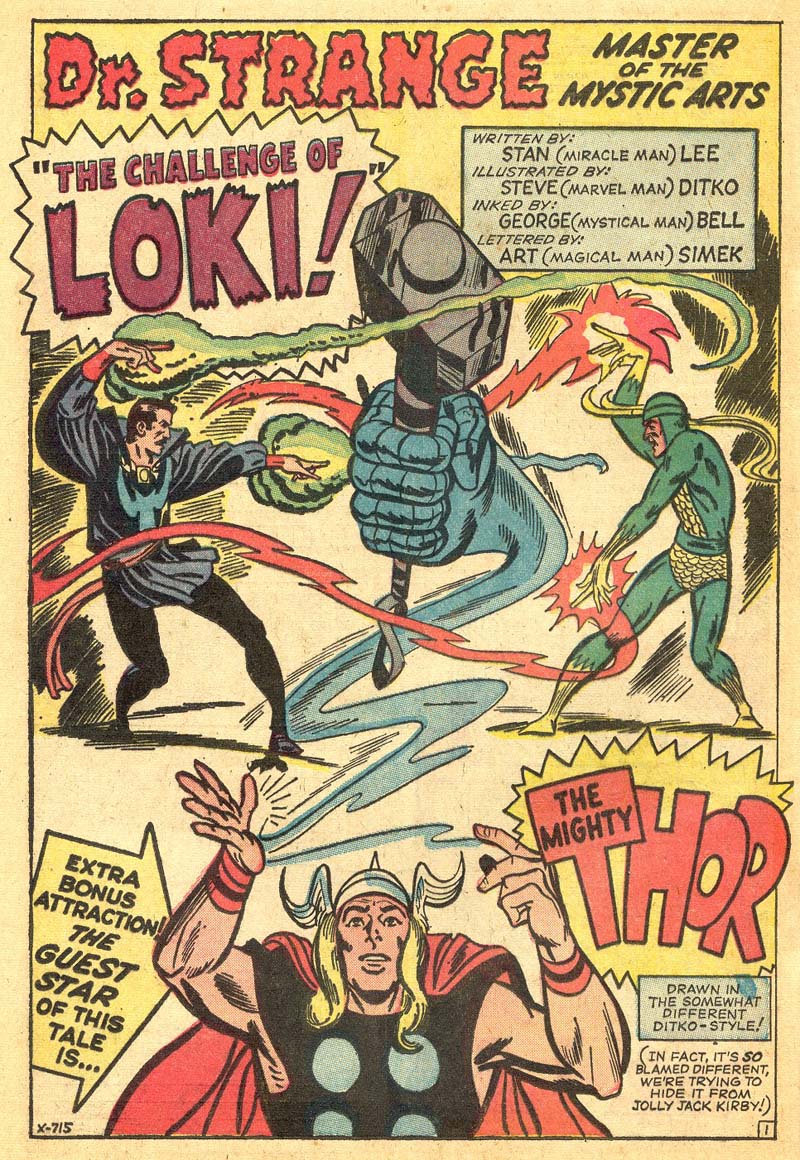

I think I first read Stan Lee and Steve Ditko’s story “The Challenge of Loki” in a black and white reprint edition when I was around 8 or so. It’s originally from Strange Tales #123, August 1964.

It’s not exactly right to say that it hasn’t held up — I wasn’t necessarily all that into it even as a kid, though it does have its virtues. Chief among them is a kind of self-contained inevitability; plotting that opens and closes with a satisfying “click.” In the story, Loki decides to use Dr. Strange to destroy his old enemy, Thor. He convinces Strange to cast a spell to rob Thor of his hammer while Thor is in flight. Without the hammer, Thor starts to fall to his death. Dr. Strange realizes he’s been tricked, and he and Loki battle. Strange is losing, but manages to reverse his spell, winding time backwards and returning the hammer to Thor. His life and hammer restored, Thor sets out in search of Loki, arriving at Dr. Strange’s sanctum just in time to scare Loki off and save Strange. The end.

I guess it sounds convoluted in the telling, but, again, the thing I sort of liked about it, and still sort of like about it, is the neatness of it — the way the story so swiftly and so unapologetically sets itself in motion, and then resets, or erases itself. Loki has an evil plot; it is discovered; everything goes back to normal. It’s transparently unmotivated, and then gratuitously rubbed out — pulp piffle which revels in its own greasepaint-daubed inconsequence. The gaudiness of the lack of pretense is refreshing — though also, admittedly, a little unsettling.

That hint of wrongness, might, perhaps, be tied to some of the characteristic tensions in Ditko’s work. Specifically, Craig Fischer argues in this lovely essay, in which he connects Ditko’s obsession with eloquently gesturing hands to the anxiety and unease which pervades the artist’s oeuvre — and then (obliquely) connects both the hands and the anxieties to repressed themes of abuse.

Certainly, hands are very important in “The Challenge of Loki.” Dr. Strange steals Thor’s hammer from him by generating a giant, blue/black hand.

In part, the hand can be seen as pointing directly to Ditko himself; the elaborate motion lines an excuse to show the squiggle of the pen line — the diegetic hand as artist’s hand drawing the diegetic hand. The comic is showing you its own grinding mechanisms; it’s showing you the man (and the hand) behind the curtain.

What the man behind the curtain is doing, of course, is wreaking havoc. Thor is sadistically thrown to his death by the mystic hand — or, if you’d prefer, by the hand of the artist. There’s no motivation, other than Loki’s almost pure malevolence — which both is a plot device, and can be seen as characterizing pulp plot itself. The narrative almost figures artist as supervillain.

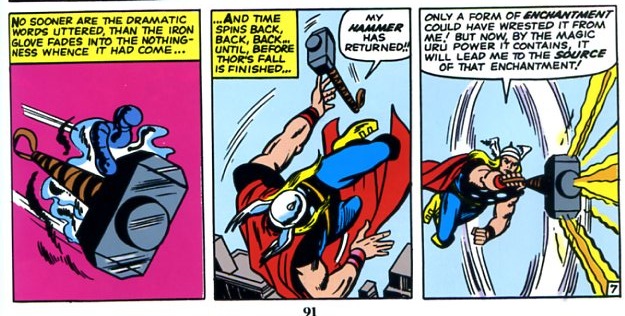

But then, of course, the artist relents.

It’s interesting that the hand does not return the hammer, but instead fades away. Time is wound backwards (though, again curiously, this is not really visualized). Thor’s hammer is returned to him; the supervillain artist erases his own work. Not only is recompense made, but, apparently, the evil was never done. It effervesces, like a dream — or an instantly forgettable chunk of pulp detritus. There’s almost a wistfulness there — a fantasy that those hands (my hands? whose hands?) had never been or done; that they could just vanish with a wave of (the same?) hand.

I’m sure some folks will say that it’s a stretch to read into this story trauma or guilt or a confused identification/repudiation of an abuser. And I’d actually agree with that. “The Challenge of Loki” isn’t about abuse. It’s not about anything. It’s a stupid little story about Dr. Strange fighting Loki, with Thor thrown in for cross-promotional purposes. It’s well-constructed, and mildly entertaining, and that’s all that can be said for it, really. It’s inconsequential genre product. If there was ever anything more there, it has been scoured out by some violent or gentle hand.

These pages make me wonder if Ditko had been assigned THOR and Kirby AMAZING SPIDER-MAN what the difference would have been in sales/popularity.

Stan Lee has a little quip on the cover about how different Ditko and Kirby’s styles were….

It’s funny; I got the Dr. Strange collection I have out to write this, and happened to show it to my 9-year-old, and he is really into it. He says he likes the way all the characters talk to themselves (he thinks it’s funny), and also the little captions in the credits (“this issue necromantically drawn by Steve Ditko!” or whatever.)

Those colors are awful!

Yeah; I was actually thinking you would hate them when I was looking at them.

Oh, and I agree with you. I don’t know why they have to be so gaudy and ugly. I guess someone prefers them that way? I dunno….

An editorially mandated crossover, inked by someone else, in the fallow issues of Strange Tales in which the magician hero saves the day with an out-of-nowhere power to reverse time…

And, Ditko’s gesturing hands as repressed memories of molestation; this outdated junk psychology is introduced but then dismissed as if to suggest the work is poorer for not having anything to do with it.

Couldn’t you have found a better Ditko to talk about?

If I ever see a better Ditko story, I guess I could. I’ve never read anything by him that rises above pulp dreck, though. And yes, that includes the classic spider-man stories. He’s just a really pedestrian creator content-wise, though he’s got a stylish visual sense, obviously.

I think Ditko would have been a much, much, much more interesting writer if he had actually managed to write more straightforwardly about the anxieties that seem to shadow his work. But that’s me.

I think you’re on to something larger with the trauma/abuse undercurrent in those seemingly meaningless old stories, Noah. Actually, I wonder if their very meaninglessness is what makes them so fascinating in the first place.

Pulp narratives are equipped to address trauma in ways self-consciously literary narratives sometimes fail to do. I’m thinking, for example, of so much of Cornell Woolrich’s work, or Norvell Page’s brutal Spider novels. Maybe these stories have this blunt power because they read like letters from the subconscious–or “automatic writing for the common man,” as Walter Ong once described Walt Kelly’s Pogo? The suppression of the pain and shame associated with trauma might be expressed evocatively in a text which is itself actively seeking to sublimate emotion and meaning–the Dr. Strange story almost becomes an example of expressive form. It’s then up to the reader or the critic to create a narrative of what is happening in this seemingly blank space, and that interaction between the reader and the text is also fascinating.

This essay made me think again about Fritz Leiber’s _Our Lady of Darkness_, where he plays with all those pulp genre conventions in a story about alcoholism, grief, and loss. But that novel, or short stories like “Smoke Ghost,” could just as easily be read merely as really eerie ghost stories, too.

I think there are definitely pulp works which are able to deal with or think about trauma in interesting ways. The Marston/Peter WW does it in some places…and of course so does LOTR. And, actually, Alan Moore does; arguably in Watchmen with Rorscach he’s fleshing out some of the issues that Ditko deliberately avoids.

All of those are more direct than Ditko by a lot, of course. Ditko’s somebody who I feel like could have been an artist I really liked, but it’s just not quite there. (Unlike Kirby, who doesn’t really offer me much of anything, withheld or otherwise.)

“and happened to show it to my 9-year-old, and he is really into it.”

That’s interesting. He might be at that age just before the “cool sense” kicks in. Within a few years he might not be able get into stories like that. How do you think he would react to Jack Kirby’s New Gods with all its purple dialogue?

“I think Ditko would have been a much, much, much more interesting writer if he had actually managed to write more straightforwardly about the anxieties that seem to shadow his work”

That’s the problem with writing too much pulp. You forget (or never learn) about how to write about yourself. Instead, we get Ditko in the seventies hectoring other writers about how they should stop focusing on the “negative” and write about more “heroic” subject matter.

I don’t know…some pulp writers engage personal material in various ways. And I don’t even know that it has to be personal, per se. I mean, I don’t know what his biography is or isn’t. I just always feel with him like there are things going on in his work or issues he’s interested in that don’t manage to get expressed or dealt with in a way that’s effective.

It could really be the ideology rather than the pulp, is the truth. His philosophy is just so dumb that I can see it interfering with his ability to say anything worthwhile in all sorts of ways.

I’d say its both. As long as you’re writing stories that rely on fistfights for climaxes then right there you’re walking into a trap. Don’t remember seeing too many punches in Marston’s work.

Heh. He’s not above a fisticuff or two. Just so long as it all ends in someone being tied up….

Do you read Watchmen as pulp, Noah? That’s interesting. I always think of it as a more self-consciously literary work–or at least a commentary on pulp and genre conventions.

(And I’ve never read LOTR so I don’t know how that narrative works. I need to read them someday.)

I guess I think of pulp as works like this Ditko story, or Walter Gibson’s Shadow novels, for example, where the personal voice/viewpoint of the writer (or artists) must be concealed–or erased!–to serve the demands of the publisher, which needs a product to sell, and the audience, which has certain expectations of the character or the genre.

But then again I also love the tension between the two–the demands of the publisher/audience and the viewpoint of the artist. Things get interesting when two start to conflict with each other and we get images like the trembling, anxious hands on Ditko’s characters.

You haven’t read LOTR!!! It’s so good; I’m just rereading it to my son now.

I may be using pulp too loosely; maybe genre is the word I want. I do think of Watchmen as both commenting on and participating in pulp traditions, I guess.

Do I start with The Hobbit or did he write the trilogy first?

I don’t know why I never read them. My dad loves the books, and he’s almost strictly a nonfiction reader. I remember we had the paperback editions with the Piper at the Gates of Dawn-like psych images on the covers. Somehow I got sidetracked by Moorcock’s Elric novels and never made my way back to Tolkien. Have to add those to my reading list.

Speaking of pulps and their audiences, Erin Smith’s book Hard-Boiled: Working Class Readers and Pulp Magazines is a great book on genre conventions and reader expectations:

http://www.temple.edu/tempress/titles/1405_reg_print.html

He wrote the Hobbit first, and it comes first; starting with it is the way to go (it is also great. Much, much better than Elric, IMO.)

“I think Ditko would have been a much, much, much more interesting writer if he had actually managed to write more straightforwardly about the anxieties that seem to shadow his work. But that’s me.”

Irrational fool! A=A!

A=A, motherfucker.

…seriously, though, Ditko seems like one of those cartoonists who’s interesting to read for very different reasons from the ones he would suggest you should read him for. (See also: Dave Sim)

——————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

If I ever see a better Ditko story, I guess I could. I’ve never read anything by him that rises above pulp dreck, though. And yes, that includes the classic spider-man stories. He’s just a really pedestrian creator content-wise, though he’s got a stylish visual sense, obviously.

I think Ditko would have been a much, much, much more interesting writer if he had actually managed to write more straightforwardly about the anxieties that seem to shadow his work. But that’s me.

———————-

It would’ve been interesting to see Ditko adapt Kafka, or Poe; literary talents closest to what he’s most inspired by. Certainly he’d be the wrong creator to do a Henry James tale…!

For the whole arc of Ditko’s career, clearly it’s the lurid, exotic, hyper-emotional that inspires his art.

Just like Frazetta would’ve been a dud at doing high-society portraiture, and Clive Barker (a talented artist in his own right) said he couldn’t get into what he called “barn door painting” [cf. Andrew Wyeth]), “pulpy” stuff — lurid, melodramatic, violent, bizarre — floats Ditko’s boat.

Anything more emotionally/intellectually subtle wouldn’t interest him; how natural that he’d get into Objectivism, A = A philosophical simplemindedness.