“Tell me one last thing,” said Harry. “Is this real? Or has this been happening inside my head?”

“…Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?”

–Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows

Writing on the Game of Thrones season three premiere, a reviewer at the New York Times who confessed to being a fan of the science fiction and fantasy genre casually mentioned that upcoming discussions on slavery and women’s liberation were “heavy handed…particularly for a show set in the medieval period.” Twitter reacted swiftly, with Alyssa Rosenberg from Think Progress satirically tweeting, “may the Lord of the Light save me from people who are made uncomfortable by thinking about issues in their entertainment.”

Shunted away, at a private kiddie table and apart from allegedly serious literature, fantasy fans have been jostling for recognition and fending off accusations that their beloved genre is immature, escapist, and unrealistic. High/Epic Fantasy, in particular, has been accused of being regressive, conservative, and reactionary, intent on preserving an ideology of traditional gender scripts and maintaining a cast of lily-white characters. In western culture(s), epic fantasy is thought to describe the British medieval period, albeit with dragons and magic, but a more accurate description would be that post-1960s epic fantasy is influenced heavily by J.R.R Tolkien, whose irritation with industrialization and what he called “the robotic age” are palpable in his idealized version of rural life as represented in the Shire. In an interview with the International Socialism Journal, China Mieville states that:

You…have to remember that many works within that tradition question or undermine its more conservative aspects. However, it is true that the hold of that conservatism is strong in the genre, and it’s also true that that particular post-Tolkien stream is what most people these days mean when they talk about ‘fantasy’.

It would be unfair to point exclusively at Tolkien for his long-lasting influence on epic fantasy when the genre’s heritage has also been influenced by commercial considerations. Between 1969 and 1974, Ballantine re-issued around seventy classic fantasies in their Adult Fantasy series and published a number of significant new authors like Ursula K. Le Guin and Marion Zimmer Bradley. However, none came close to matching the commercial success of The Lord of the Rings.

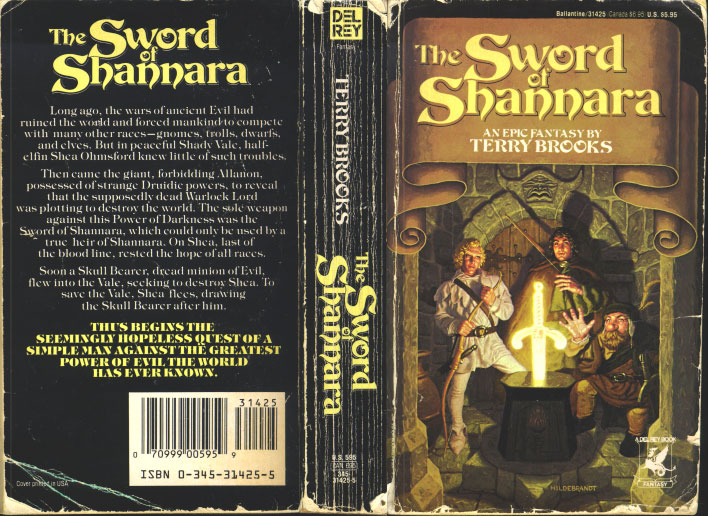

In 1977, new Ballantine editors, Judy-Lynn Del Rey and Lester Del Rey, believed that fantasy fiction could become a real mainstream success if promoted properly. As an experiment, they took two new authors out of their slush pile, Terry Brooks (Sword of Shannara) and Stephen Donaldson (The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, the Unbeliever) and marketed them explicitly as books for people who liked Lord of the Rings. Both novels were immediate best sellers and set the stage for the fantasy genre’s commercial viability. The long tradition of conservatism in fantasy has partially been the result of commercial constraints—editors know what’ll sell.

Mieville goes on to list a number of traits he associates with conservative ideology, what he also calls “feudalism lite.”

…[I]f there’s a problem with the ruler of the kingdom it’s because he’s a bad king, as opposed to a king. If the peasants are visible, they’re likely to be good simple folk rather than downtrodden wretches (except if it’s a bad kingdom…). Strong men protect curvaceous women. Superheroic protagonists stamp their will on history like characters in Nietzschean wet dreams, but at the same time things are determined by fate rather than social agency. Social threats are pathological, invading from outside rather than being born from within. Morality is absolute, with characters–and often whole races–lining up to fall into pigeonholes with ‘good’ and ‘evil’ written on them.

These labels pose a challenge to engaged writers and readers of the genre who love the epic fantasy tradition but do not necessarily believe in its innate marriage to escapism, and maybe don’t even believe in conservative ideology’s innate attachment to escape either. Mieville, for his part, has all together eschewed the rural setting so prevalent in epic fantasy and has chosen to feature heavily urbanized settings in his writing.

The conservative tradition Mieville describes is, of course, not the same as American-style conservatism and refers to British high toryism (similar to Canadian red toryism), an ideology which accepts the presence of class inequalities and traditional social stratification as long as society elites provide, through charity or government legislation, assistance to the marginalized. Key words: nobless oblige. Critics of High/Red Toryism describe the ideology* as paternalistic, as its justifications for social stratification have historically relied on a mandate from God. If ever you wondered about the rampant use of prophecies in epic fantasy, then consider its link to high toryism: birth is destiny.

Questions of free will aside, these prophecies often form the basis of what Joseph Campbell calls “the hero’s journey.” Hero leaves home, finds magical helper, overcomes trials, receives rewards. (I call this description the “plot coupons” formula, where the reader can cash in these coupons for a feel-good adventure. Hero finds magic cat; Hero finds magic sex; Hero defeats magic villain etc.) Royalty often provide structure to these quests, functioning as characters that recognize the hero’s achievements, set the hero on his or her quest, or punish the villain.

In her doctoral thesis, Kings. What a Good Idea, Pamela Freeman writes that in stories in which a king is the protagonist, we’re likely to see the oft-used “Rightful Heir” or “Missing Heir” trope. See: King Arthur, Aragorn, Harry Potter, Rand from The Wheel of Time, Eragon, and most novels that involve a young boy that leaves his home to embark on an adventure. On one hand lie patriarchal inheritance laws that govern the transmission of inheritance between male blood lines, an issue of justice and fairness that is familiar to most people, despite or because of its problematic gendered connotations. On a more emotional level, there’s hunger to belong and to complete a family, that the truth about one’s blood line and birth status is worth knowing and that without the truth the person will live a suspended life fraught with emotional anxieties. Conservative or not, this plot-line directly confronts our emotional anxieties.

The question then becomes why people living in democratic countries would be interested in reading books about social stratification and monarchy. Pro-monarchists (the real-world kind) usually defend royalty on the basis that monarchs represent all of their citizens and thus provide continuity and identity to a nation, whereas elected officials can only represent their constituents. (For those who say, “but…presidents?” most pro-monarchists live in constitutional monarchies that use a parliamentary system. Prime Ministers aren’t directly elected by the people.)

Freeman states that “tyranny has been replaced with an image of pastoral care, ensuring that today will be like tomorrow, protecting us from political machinations and…extremes of any kind.” She links a distrust of elected officials and desire for continuity with epic fantasy’s focus on “rightful kings.” Writers use kings precisely because they’re traditional, and therefore meaningful. Of course, the common image of a rightful king preserving the collective peace amongst his people is a historical judo-flip unsupported by an even cursory empirical observation but, nevertheless, rightful kings prance around and disseminate compassionate justice in epic fantasies with more regularity than they ever did in history and this has led critics to deride the genre as escapist because it’s not “real.”

But labelling the epic fantasy genre as unserious also stems from the 19th century rise of the modernist tradition that undervalues story and prioritizes style. Traditionally, epic fantasy is told conservatively and is rarely experimental, omitting surprising shifts in time or point of view. This ordered narrative prioritizes story-telling by giving readers access to familiar non-experimental style, which consequently allows them to suspend skepticism (or to even believe, as Tolkien states in his lecture On Fairy Stories) without awkward mental breaks that would shatter the belief of the secondary world. In a much quoted passage, E.M Forster articulates the modernist position on storytelling, calling its relationship to the novel as “the backbone—or may I say tapeworm, for its beginnings and end are arbitrary. It is immensely old—goes back to Neolithic times, perhaps to Paleolithic. Neanderthal man listened to stories, if one may judge the shape of his skull.”

The fantastic’s historical link to oral folk ballads and storytelling is fairly obvious, but this modernist disdain for its oral roots reveals Forster’s elitism: if it’s not difficult to read, then it’s not worth the reader’s time. This position, while also being classicist, neglects oral storytelling’s influence on knowledge. (I wonder about Forster’s position on university lectures.) This elitism hasn’t disappeared from modern publishing. In his famous 2001 essay titled The Reader’s Manifesto, B.R. Meyers writes that fast-paced stories written in un-affected prose may be deemed “an excellent read” or a “page-turner,” but “never literature with a capital L.”

The modernist backlash comes on the heels of the Victorian period’s Arthurian resurgence, a shift created by popular writers like Walter Scott, Alfred Tennyson, and William Morris. Tolkien was especially keen on Morris’ romances, stating that “other stories have only scenery; his have geography.” We have Morris to thank (and not sarcastically!) for the creation of Tolkien’s maps, revolutionary at the time of their publication and now staples in nearly every epic fantasy novel. It bears noting that even during their lifetimes, authors like Walter Scott were accused of prettifying history and creating a market for nostalgia. Mark Twain wrote A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court as a reaction to Scott’s writing. Twain writes:

Then comes Sir Walter Scott with his enchantments, and by his single might checks this wave of progress, and even turns it back; sets the world in love with dreams and phantoms; with decayed and swinish forms of religion; with decayed and degraded systems of government; with the sillinesses and emptinesses, sham grandeurs, sham gauds, and sham chivalries of a brainless and worthless long-vanished society. He did measureless harm; more real and lasting harm, perhaps, than any other individual that ever wrote.

I hear protests in the background. “But what about Ursula K Le Guin? What about the Hugo Awards, whose organizers have been keen to diversify the fantasy genre?” That’s exactly it—there’s nothing innate about epic fantasy that requires its marriage to conservative philosophy. (And even Mieville doesn’t believe Tolkien’s influence has been totally negative.) In fact, fantasy is uniquely positioned to play with radical ideas.

Radical, of course, is not the same thing as realistic. In reaction, or perhaps in retaliation, to critics who accuse fantasy of being unrealistic, a sub-genre of fantasy called “grimdark” has emerged featuring grittier and darker storylines. Joe Abercombie, arguably the posterboy of grimdark fantasy, writes “[p]ortraying your fantasy world in a way that’s like our world? That’s only honesty.” Even fantasy that is not officially “grimdark” bears traces of the shift from shiny and clean to gritty and dirty. However, writing recently on the movie Lincoln, Aaron Bady ushers in a glorious takedown of those who equate grittiness with reality.

First and foremost, it uses a realist aesthetic to make it seem like compromising cynicism is realistic. Form becomes content: it shows us the world as it “really” is by adding in the grit and grain and grime that demonstrate that the image has not been airbrushed, cleaned up, or glossed over, and this artificial lack of artifice signifies as reality…They don’t mean “accuracy,” because that’s not something most people could judge; they mean un-glamorized, un-romanticized, dark…

But, of course, we’re not. We’re just seeing a movie whose claim to objective accuracy is no less artificial than the filters by which an instagram takes on the nostalgic glow of a past that was never as overexposed and warm as it has become in retrospect. And when we take “gritty” for “realism,” another kind of “realism” gets quietly implied and imposed: the capitalist realism by which ideals become impossible and the only way things can get done is through compromise and strategic surrender. Anti-romanticism is all the more ideological because it pretends to have no ideology, to be the “plain truth” that demonstrates the falsity of romantic visions.

Whether a story is romantic or gritty is hardly a measure of reality or progress—Game of Thrones is very conservative despite its grittiness, after all. In either case, I’m not sure when novelists started conflating “realistic” with “relevant” or “truthful.” Employing a realistic aesthetic is not something fantasy should necessarily aspire to be, nor does a realistic aesthetic make a novel meaningful. Regardless of literary tradition, most writers are dedicated to sincerely lying. Particularly useful to this discussion is Le Guin’s introduction to The Left Hand of Darkness where she argues that writers “go about it [telling the truth] in a peculiar and devious way…and telling about these fictions in detail and at length…and then when they are done writing down this pack of lies, they say, There! That’s the truth!” Generic literary novels also play with the truth, and arguments that literary novels are “realistic,” as though they are not bound by ideological constraints and a particular worldview, are fairly humorous. Epic fantasy is a massive meaningful lie/truth.

In Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion, Rosemary Jackson describes fantasy as a “literature of desire” which works to undermine cultural constraints, as a subversive manifestation of the forbidden and taboo, and as an act of imagination that undermines the world. Jackson, of course, also believes that, of all things, The Lord of the Rings is a failed fantasy because it’s sentimental and nostalgic and would rather define the book as a faery romance. However, putting aside the obsession with trying to define epic fantasy (for some academics will insist that there are differences between “high” and “epic” fantasy, while others will tell you that there’s no difference between fantasy and science fiction—drowning in a quagmire is not on my bucket list), Jackson rightfully points out the awesome potential of fantasy to play with the unacceptable.

Tolkien, for his part, argued that fantasy recognizes reality, but didn’t need to be confined by it. “For creative fantasy is founded upon the hard recognition that things are so in the world as it appears under the sun; on a recognition of fact, but not a slavery to it.” Even in conservative-minded fantasies, the opportunity to subvert expectations exists. That’s why, to return to our intrepid NYT reviewer, homogenizing the medieval period as entirely regressive and unconcerned with moral questions is unhelpful and inaccurate.

Chronology is not an indicator of progress. The term medieval is pejorative, often used as a synonym for unenlightened (for what came afterwards?) and anti-intellectual, even though the period’s philosophical contributions still affect us today. If we want to talk about “realistic” warfare, then how can we ignore Thomas Aquinas and St. Augustine’s contributions to Just War Theory? Today, we see so-called history used as a slight of hand to give books a carte blanche against criticism. “That’s just how it was back then,” a period defined as anything pre-1950s if judged by fan conversations on the interwebz. Unfortunately, these excuses homogenize history and ignore its radical and not-so-radical thinkers who would protest at, say, the harshness of contemporary life. Who could forget Thomas More’s Utopia, the Renaissance book that birthed the utopian and dystopian novel, subgenres dedicated to undermining the status-quo but, according to the it’s-only-entertainment brigade, born in a period with allegedly unquestionable moral absolutes that cannot be addressed in entertainment. More’s Utopia bends, challenges, and re-imagines the realities of his day more honestly than many fictions claiming objectivity. While most wouldn’t classify Utopia as an epic fantasy work, the point still applies: many imitations of historical time periods aren’t realistic even when they claim to be, but even if they were, what does that have to do with meaning? Literature must do more than imitate.

These subversions also occur in the Arthurian canon, the prototypical conservative epic fantasy. When BBC’s Merlin hired Angel Coulby, a mixed-race actor, to play Guinevere, the fan reaction was divided by those who argued that a black Guinevere couldn’t exist in the medieval period, that her presence was anachronistic, and those who believed that the mere act of casting Coulby was revolutionary. It’s saddening that a medieval text is potentially more progressive than some modern fans who shout down calls for diverse representation. Two Moorish knights were members of the Round Table and, lest we forget, the Green Knight was actually green skinned in early versions of the tale. But here again, we have an erroneous view of the medieval period as disconnected from the rest of the world. Here again we see people use the term “reality” to claim that an idea is objective when it’s actually ideological.

Despite its conservative nature and the fact that it happened “back in the day,” the Arthurian cannon isn’t silent on gender roles either. In 1911, Silence was discovered in England, a 13th century epic poem that forms part of the Arthurian canon and was originally written in French. The main protagonist is Silence, a girl who is raised as a boy due to King Eben’s declaration that women cannot inherit property. Nature and Nurture are personified in the poem, and take turns debating whether gender is either innate or socialized. Can Silence successfully become a man? Though Silence contains a number of problematic elements, the fact that epic fantasy was discussing gender in the 13th century should be enough evidence to dispel the myth that epic fantasy is escapist and unconcerned with the human condition simply because it does not follow our world’s physical laws.

Furthermore, despite commercial tendencies to sideline characters of colour and systemic authorial failures to incorporate people of colour in their work, Gregory Rutledge, writing specifically on African-American literature but also on themes that can be extended to other minority groups, states that the fantastic tradition is perfectly situated to discussing themes of otherness. “Otherness and the otherworld phenomenon of both fantasy and futurist fiction is something with which many persons of African descent may identify. Relegated early to the position of the exotic Other, Africans and their descendants have been marked as primitive for centuries.”

He goes on to relay that while Samuel Delaney could be considered the first self-described African-American speculative fiction author (Delaney eschews the term “fantasy”—but we’re not going there), elements of fantasy nevertheless manifest themselves in African-American literature before Delaney’s debut and even make an appearance in Frederick Douglass’ autobiography. After Douglass was whipped for the first time, he received a root from a fellow slave to evoke spirits to ward off further whippings. Though Douglass unequivocally states that this act was superstitious nonsense, he also admits that no one whipped him ever again. Here we have an example of the fantastic being evoked in discussions of physical freedom, maybe ambivalently by Douglass but with certainty by the fellow slave who offered him the root. Escapist? To paraphrase Terry Prachett, jailers hate escapism.

Even the most formulaic epic fantasy novel plays with the author’s desire, and it is therefore chained by human emotion to the so-called real world–and so it becomes an acceptable target of social criticism or praise. Criticisms targeting epic fantasy’s relevance to the human condition are uncharitable and as the genre gains more traction on television networks, new and old fans are deflecting criticisms of their most entertaining shows by borrowing the old elitist line that fantasy is irrelevant and thus immune from rigorous analysis. We’ve been rather unfair to a genre that can shape reality to its will. Creators do not escape from reality, but bend it to suit a particular idea or agenda and that, for me anyway, has always been the lure of epic fantasy.

*I do not use “ideology” as an insult. Everyone operates through ideology, on both left and right.

About the Author: Sarah is still waiting for her six-figure advance. In the meantime, she acts as a guest lecturer at Chernivtsi National University (that’s in Ukraine) in Canadian Politics. She’ll soon return to Canada –where winter is ALWAYS coming— to begin her PhD at McMaster University. You can follow her on twitter @sarahshoker.

“To paraphrase Terry Prachett, jailers hate escapism.”

Pretty sure that’s attributed to C.S. Lewist or Tolkien, not Prachett, and Michael Moorcock’s rebuttal is great:

“Jailers love escapism. What they hate is escape.”

The internet says Terry Prachett, but it’s possible that it’s not attributed to the right person. That being said, I’ve seen no indication that it’s by C.S Lewis, and it would be ideologically bizarre for Tolkien to say something like that since he was anti-analogy.

I’m aware of Michael Moorcock’s rebuttal (also copied by China Mieville) but I don’t read this quote in the same was as he does. My response to Moorcock/Mieville would be that his reading of this quote is uncharitable. The quote gets it zing by using a pun, and Moorcock/Mieville decide to read the quote literally, which contradicts its fun and witty spirit. The jailer, in this context, is not a real jailer, but a reference to the dominant (literary) ideology or elite who absolutely hate escapism.

Apparently its a paraphrase of something C.S. Lewis and Tolkien said, going by a google search, though Pratchett may also have said it:

““Why should a man be scorned, if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it. In using Escape in this way the critics have chosen the wrong word, and, what is more, they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter. just so a Party-spokesman might have labeled departure from the misery of the Fuhrer’s or any other Reich and even criticism of it as treachery …. Not only do they confound the escape of the prisoner with the flight of the deserter; but they would seem to prefer the acquiescence of the “quisling” to the resistance of the patriot.”

? J.R.R. Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories”

http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/22755-why-should-a-man-be-scorned-if-finding-himself-in

Arthur C. Clarke attributes it to C.S. Lewis:

http://goo.gl/7A5A4

And China Mieville attributes it to Terry Pratchett. It’s possible that Pratchett was inspired by Lewis or Tolkien, or that it has been sourced incorrectly.

Personally, I’m just surprised that it hasn’t yet been attributed to Betty White or Morgan Freeman.

Yeah one would imagine Pratchett was inspired by Lewis or Tolkien.

I think Moorcock is correct but so is C.S. Lewis. Jailers would frequently have no problem with conservative escapist stories that do not threaten the dominant ideology.

Patting yourself on the back because you read “escapist” fantasy stories is a really dubious thing to do.

On the other hand, stories which question the dominant cultural assumptions may be hated by jailers , though frankly that’s done far more often in the science fiction genre.

I haven’t seen Game of Thrones, so I can’t really comment, but you’re being at least a little unfair to the New York Times critic, the actual quote was:

“Game of Thrones” bears a startlingly close resemblance to shows like “Boardwalk Empire” and “Band of Brothers.”

The early episodes of Season 3 contain another sign of premium-cable conformity: plots or situations that address themes of slavery, women’s empowerment and sexual orientation in obvious, heavy-handed ways, particularly for a show set in a medieval fantasy world.”

He’s arguing in part that the that the show is following the Cable TV formula. What’s interesting is the claim by Alyssa Rosenberg that a show (allegedly) just like every other show on Cable TV will make viewers think.

I’ll just say really quick that I’m not totally sure that A Song of Ice and Fire’s politics can be labeled “conservative” that easily. While the identity politics of the books are complicated and problematic (you’ll get no argument from me there, there isn’t a single adult woman in those books who isn’t some mix of stupid, manipulatively sexual, venal, and/or wrong about everything, and in Book 5 as Danarys gets closer to being an adult, she gets closer to being all of these things), I would hardly call it a conservative position that war is an inglorious, often futile pursuit in which the lower classes pay a very high price for the vanity and mendacity of the rich in which there is literally no possibility of ennobling oneself. Nor would I call the book’s portrait of organized religion as essentially corrupt and power hungry particularly conservative.

“Patting yourself on the back because you read “escapist” fantasy stories is a really dubious thing to do.”

I’m not sure anyone’s patting themselves on the back when fantasy fans are often on the defensive. They really shouldn’t be.

Re: Sci-Fi being more interested in subversive issues etc. In the same Ursula K. Le Guin essay that I quote in this article, she mentions that many people don’t like sci-fi for the very reason that they label it as escapist, too.

Re: NYT critic…that’s why I said he “casually mentioned” that it was heavy-handed for a medieval fantasy world. I acknolwedge that it was an off-hand comment, but he’s saying that it shouldn’t imitate other cable shows because it’s just “too much” for a show set in a quasi-medieval period. That’s what I’m addressing.

Hi Isaac,

I should have probably been more clear, but the link I highlighted when I talk about GoT conservatism is actually referencing the HBO adaptation. Though, I’m not necessarily sure that holding a “war sucks” position automatically nullifies a book’s conservatism. Edmund Burke didn’t think that all wars were just, after all. Nevertheless, even Tolkien is hailed by some progressive environmentalists. It’s rare to find a book that’s 100% partisan. I will stick with the claim, however, that there are very very deep conservative strains in Martin’s work.

For what it’s worth, the “jailers” quote is from Lewis’s 1955 essay “On Science Fiction,” collected in Of Other World (1966) and elsewhere:

“That perhaps is why people are so ready with the charge ‘escape.’ I never fully understood it till my friend Professor Tolkien asked me this simple question, ’What class of men would you expect to be most preoccupied with and most hostile to, the idea of escape?’ and gave the obvious answer: jailers. The charge of Fascism is, to be sure, mere mud-flinging. Fascists, as well as Communists, are jailers; both would asure us that the proper study of prisoners is prison.”

Thanks, Peter! Pratchett talks about the same theme, but it seems like the original stems from Lewis.

http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/526477-fantasy-is-escapism-but-wait-why-is-this-wrong-what

Mervyn Peake took on class while writing some of the 20th century’s richest fantasy fiction.

“Re: Sci-Fi being more interested in subversive issues etc. In the same Ursula K. Le Guin essay that I quote in this article, she mentions that many people don’t like sci-fi for the very reason that they label it as escapist, too”

The highest grossing films of all time list is dominated by scifi and fantasy. Marvel’s making a killing this week on a ridiculous scifi movie called Iron-man 3, 73% positive reviews on Rotten Tomatoes. I feel like framing the critical issue this way is very dated.

There are plenty of sci-fi and fantasy fans, but they’ve been jostling for recognition as a serious genre. This isn’t an argument trying to dispute fantasy’s popularity, but its relevance as something on par with the quality of capita-L Literature.

Great, thoughtful essay!

I’ve never been able to figure out why, over the years, I’ve gravitated towards writers like Robert E. Howard, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Andre Norton, John Norman (Lange), Philip K. Dick, and E.E. “Doc” Smith, but could never finish a book by the likes of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, or J.K. Rowling? Just with the authors I MENTIONED, We’re talking a ratio of ABOUT 60-70 books to zero.

There’s something about elves, fairies, trolls, wizards, warlocks, witches, talking animals, etc. that just never struck the right fantasy chord in me. It’s probably why, when folks around me went nuts about “Dungeons and Dragons” back in the 1980s I was like, really? I don’t get it. Ditto for comics such as “Elfquest.”

Even today, while I’m an avid gamer, the pure role-playing stuff like “The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion” leaves me cold. I played it a couple of hours a year or so ago and that was it.

The movie versions of the books by those authors are a slightly different story, as I’ve sat through almost all of them. But while I apparently can handle a two-hour Narnia film, I just can’t get through one of C.S. Lewis’ books.

I’m not sure why.

PKD has really extremely little in common with Howard or Burroughs. fwiw.

Thank you, R. Meheras. I’m glad you liked it. I’m a pretty big fan of PKD, too, moreso than Tolkien, though probably on par with C.S Lewis’ fantasy novels(I really can’t handle his sci-fi.)

I do find that the presence of other races can be off-putting for some readers, but I’m not sure why that’s the case. Is it that the ability to empathize is reduced? Or does it just seem silly and juvenile? That might be something to investigate further, m’thinks.

I recently listened to a lecture series by one Professor Drout called “The Modern Scholar: Rings, Swords, and Monsters: Exploring Fantasy Literature.” I’ve also listened to a free fantasy and SF lecture series from University of Minnesota that they seem to have taken off their website; fantasy writer Pat Hodgell was cohost. Both dismissed Robert Howard as a purveyor of meatheaded power fantasies, and seemed to take particular umbrage at Conan’s wizard-killing, seeming to interpret this as a desire to kill pointy-headed cultural elites. On the basis of my (admittedly minimal) reading of Howard’s work, this dismissal is dopey, but it crops up in at least 2 audio lecture series I’ve found.

Oh yeah, both of them refuse to mention Mervyn Peake, because hey, why would you?

” Creators do not escape from reality”– this statement alone bears repeating.

An excellent article of which I really can’t find anything to argue with. Although, I would interested in the author’s take on the latest Iron Man movie.

That’s a good piece. Mervyn Peake is pretty excellent, but his vision of the palace as a pretty utterly corrupt place, which is fabulously Gothic and sort of an American version of conservative as well– kings are stupid, aristocrats are stupid, but the revolutionary destructiveness of enterprising educated types is the only hope.

I do realize he is British. Much like Anthony Burgess, who is a Peake fan and wrote an incredibly weird homophobic dystopia I’m sort of reading.

This article is super thoughtful, and provides a nice gloss on why the fantasy genre has been labeled conservative (this is something I hear from time to time, but never looked into).

It’s times like these when I wished I’d cottoned to the genre so that I could engage more meaningfully.

John Lanchester recently wrote a piece in the London Review of Books about Game of Thrones. The first few paras are particularly a propos to some of the issues discussed here, e.g.:

“[…] For reasons I’ve never seen explained or even thoroughly engaged with, there seems to be an unbridgeable crevasse between the SF/fantasy audience and the wider literate public. People who don’t usually read, say, thrillers or military history or popular science will read, say, Gone Girl or Berlin or Bad Pharma. But people who don’t read fantasy just simply, permanently, 100 per cent don’t read fantasy.”

PS: hooray for Peake!

Re: China Miéville, while the urban setting in Perdido Street Station is a welcome change of pace from the pseudo-rural settings of Tolkien et al, I was actually disappointed that Miéville’s socialist politics didn’t come into play more. There’s certainly a lot of class awareness and there are even some scenes involving labor unrest in New Crobuzon, but these are by no means the main focus. This is also true in The Scar, which takes place in the same world, though not in New Crobuzon itself. I haven’t read The Iron Council yet, but apparently it’s the most overtly “political” of the three Bas Lag novels.

Re: Mervyn Peake, yeah Gormenghast castle is quite corrupt with its aristocratic class trapped in meaningless roles and rituals for the benefit of no one. Peake spent time as a missionary in China and he modelled Gormenghast Castle and its rulers on Beijing’s Forbidden City and various Chinese emperors/dynasties, though of course he presumably had European models in mind as well.

Re: Elfquest Since Russ mentioned it (as something he never really liked), I’ll just say that when I first encountered it, one of the things that appealed to me about it was that its setting and overall aesthetic owed very little to Tolkien or the pseudo-medieval Europe that one generally associates with post-Tolkien fantasy; instead, the Pini elves seemed conceptually (and sartorially) to draw more on a Native American look and feel. In fact, at the same time I was first got into EQ (1979-80), I was also learning about the Iroquois in school and I could easily recognize certain aspects of the wolfriders in Iroquois mythology and this very much contributed to my enjoyment of the series.

Le Guin was somebody who very consciously went a different way from Tolkien. Earthsea is sort of Pacific Islandish…much more about anthropology than medievalism. It actually sort of ends up somewhat conservative in some ways though…the newfangled means of cheating death are shown to be corrupt and evil.

Which sort of brings up an interesting point that Bert touches on…which is that in a capitalist society, conservatism isn’t necessarily unprogressive. Or at least, conservatism isn’t pro-capitalism, or pro the dominant ideology. There’s this weird thing in the US where libertarians are called conservative, even though they basically have no respect for tradition at all and want to tear down every possible institution in order to institute radical abstract solutions in pursuit of utopia.

Wow, that John Lanchester review of Game of Thrones is so gushingly fannish and defensive, it was like reading a Bash! Bam! Pow! article about comics only with much better style of course.That’s what you get when you read about fantasy in the LRB I suppose.

That’s probably what creates strange bedfellows like Tolkien and 60’s counterculture.

Which reminds me of the existence of the libertarian Sword of Truth series but I don’t have the stomach for what’s supposedly an objectivist screed.

Regarding Game of Thrones I realized that they way women were depicted was not up to snuff but the grim depiction of feudalism and war, the hypocrisy of chivalry and the fascinating characters keep me reading and watching. I do think it shows how women can try to get by in and exercise power in a very patriarchal society. Olenna and Cersei as an example, although I kind of hated how GRRM treated her after she got POV chapters in the fourth book. Brienne of Tarth also, maybe.

I tend to ascribe some of the blatant orientalism and conservatism to the POV storytelling but of course that’s not really an excuse since they’re still the author’s.

Suat: Hack! Slash! Crom! Fantasy isn’t just for nerds anymore!

Noah: the alliance of “conservatives” and “libertarians” isn’t weird at all, and not unique to the US. Libertarians — or at least some political and public figures who claim to be libertarians — are opposed to regulation and redistributive policy (through tax or other means) because SOCIALISM, which makes them natural bedfellows for social conservatives and the economic right. See e.g. Ron/Rand Paul’s remarks on your Civil Rights Act, or, really a whole bunch of Ron P’s views

“Re: China Miéville, while the urban setting in Perdido Street Station is a welcome change of pace from the pseudo-rural settings of Tolkien et al, I was actually disappointed that Miéville’s socialist politics didn’t come into play more.”

Mieville’s actually on the record saying that he’s not trying to write a socialist tract because he doesn’t believe in using fantasy to write analogies for the real world. I suppose you could sum up his perspective as “monsters for monsters’ sake.” I believe that Iron Council is supposed to be more political than Perdido Street Station, however. I haven’t read Iron Council, though, so I’m just repeating hearsay. He says that there are more “efficient modes of propaganda” (paraphrasing) and that he’d write non-fiction if he wanted to write a socialist manifesto. Good interview to watch on the subject: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CNTzgAbtPxQ

“Although, I would interested in the author’s take on the latest Iron Man movie.”

Ha! Well, I haven’t seen it yet, so you might have to wait.

Aaron: Thanks for citing that podcast. I’m going to have to search for it.

Noah: “Which sort of brings up an interesting point that Bert touches on…which is that in a capitalist society, conservatism isn’t necessarily unprogressive.”

Yeah, that’s the funny thing about high/red Toryism. In Canada, it’s not unusual for red tories (a dying breed now) to support federal funding for abortion, poverty-reduction programs etc. They’re a lot more likely to use the public purse in their belief that elites need to provide for the disadvantaged.

I’m actually quite a fan of Tolkien’s belief in duty (Frodo must take the ring to Mordor, even though it’s unlikely he’ll come back), though possibly patronizing, I do think we have obligations to one another and LOTR appeals to me on that level– and I’m no where near close to conservative.

Jones (quoting John Lanchester): “people who don’t read fantasy just simply, permanently, 100 per cent don’t read fantasy.”

Talking for myself only, my explanation is quite simple: life’s too short.

Jones…I get why the alliance exists. It’s just odd to call people conservative who are in fact utopian radicals.

I’m not necessarily looking for a tract, but I thought that given the richness of the setting of New Crobuzon that he’d explore its political dimensions a bit more than he did. I will definitely have to read The Iron Council one of these days.

BTW, so far my favorite China Miéville novel is The City & the City , which is fantasy only insofar as it describes a fictional nation/city. It contains no monsters, magic, cactus people or tentacles to speak of, instead, it’s a Borges-like thought experiment in the form of a “police procedural” novel. Highly recommended, even for those who declare that “life’s too short” for fantasy novels.

Sarah — Not sure my blasé attitude about certain fantasy tropes has anything to do with “other races,” as that’s a common element of the authors I enjoy, such a Burroughs. There could be an unconscious “juvenile” aversion aspect, but there are other juvenile fantasy elements that I love, like the pre-superhero Marvel Monsters, circa 1958-1962.

I’ve just never been an elf/pixie/wizard/unicorn/talking dragon kind of guy.

“Jones…I get why the alliance exists. It’s just odd to call people conservative who are in fact utopian radicals.”

We also live in a country where liberal and socialist have somehow become synonymous, with the latter word being sufficiently empty to become synonymous with Nazism (for a small, but loud group of people).

The only way the liberal/conservative distinction as it is made in the US scans is if you look at it as a way to prevent meaningful conversation about a third term like late capitalism or neoliberalism.

Sorry folks, but it’s the end of the semester and I haven’t the wherewithal to stifle my inner pedant.

R. Maheras–I think that’s a totally valid position to hold. I’m usually a little hesitant with talking animals myself. Why? Wish I knew.

Daniel–I really want to read “The City and the City.” I find the premise absolutely fascinating. I’m also interested in checking out some of his YA work. “Un Lun Dun” is supposed to play with the prophecy trope that’s so common in fantasy.

I read Railsea a while back, and I thought it was pretty good. A neat world and some interesting uses of language for a YA novel. I do need to check out some of his adult work at some point though.

+1 on the recommendation for The City and the City, and Un Lun Dun is very good YA.

Some of the best SF and fantasy has been specifically written for the YA market. Asimov, Heinlein, Le Guin, etc.

The problem with The City & The City is that even though it has an interesting/promising central SF idea, the overlying detective story is pretty mediocre. Not to mention the fact that Mieville doesn’t have the writing style to carry it. It’s a very cinematic book esp. during the action scenes and reads very much like a screen treatment in parts. I can definitely see Tom Cruise in this one. Even “second tier” Graham Greene like The Ministry of Fear seems more poignant, relevant, and beautifully written. To compare the novel to the writing of Borges would be to deny Borges any sense of mystery. It’s like Philip K. Dick without the personal spirituality and ambiguity.

I was mildly shocked that the book won so many awards but that’s before I remembered all the other award winning SF/Fantasy books in recent years.

I certainly thought that the basic concept behind The City & The City had the feel of Borges, but it’s also true that the detective story part of it felt a bit tacked on. When it came out I saw Miéville give a reading and he mentioned that the detective story aspect was intended as a tribute to his mother, who apparently loved the genre. Perhaps it would have been stronger as a short story.

A lot of novels I’ve ready recently (and liked) have that “screen treatment” feel including Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policemen’s Union and The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, Gaiman’s American Gods and The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi, all of which cleaned up on awards. Even when reading the non-fantasy Out Stealing Horses by Per Petterson I found myself able to visualize the trailer for a film version perfectly! Perhaps that’s what wins awards these days? By contrast, Gene Wolfe’s novels never have that feel and while often nominated, usually don’t win as many awards, even though at his best, he’s a far better writer than any of the above.

I can agree with that and maybe we could add a dash of Calvino into the mix as well. But it also reminded me of Les Cites obscures by Schuiten and Peeters which deals very specifically with various forms of philosophy/ideology in the form of cities.

I did read about the tribute to his mother thing and it’s definitely the most heart warming aspect of the novel. As for the characters, they’re emotionless cyphers and I have no idea why the main character would want to say goodbye to Dhatt at the end of the book. But it would be perfectly acceptable in a film because that part would be played by some famous actor (or rewritten as a famous actress/love interest).

Yep, Gene Wolfe at his best is a really beautiful writer. And I can’t imagine any of his longer books as good films. Maybe The Fifth Head of Cerberus but it would be a box office disaster.

The Fifth Head of Cerberus is magnificent. I honestly can’t imagine why it’s not better known outside of SF circles. Actually, even among SF readers I sometimes get a blank stare when I mention him to folks who are otherwise quite well-read.

Thanks for the reminder of that Schuiten and Peeters book. I glanced at it in a comics shop a few years ago and made a mental note to read it at a later time, but I had sort of forgotten about it.

Wolfe: Definitely a sad comment on SF writers and the Nebulas that they only gave him the Grandmaster award in 2012. He had to be recognized by the Chicago literary establishment first.

In my mind, The Fifth Head of Cerberus is like The Iceman Cometh of SF writing. O’Neill’s play lost out to Miller’s All My Sons for the Pulitzer and who actually considers the latter the better play nowadays? Fifth Head was nominated in the “No Award” (Novella category) year for the Nebulas – when the SFWA thought it wasn’t good enough to win a prize. What an embarrassment.

Daniel: ” Even when reading the non-fantasy Out Stealing Horses by Per Petterson I found myself able to visualize the trailer for a film version perfectly! Perhaps that’s what wins awards these days? ”

Not to mention big bucks, eventually…

Les cités obscures is not a book, it’s a series of 11 French-Belgian 44CC (44 pages paperback – cartoné – color) albums.

I may be wrong re. the lenght of the albums: Brusel, at least, is longer, if I remember correctly, and Urbicande is b&w. La Tour turns to color at the end only.

I think you’re right, Brusel is longer than La Tour which is longer than Urbicande. La fronteiere invisible is in color, L’enfant penchee is in B/W as is La Theorie du grain de sable. Les murailles de Samaris is in color. I’ve never even seen/heard of L’ombre d’un homme but your Wiki link lists it.

Thanks Domingos. I guess I’d only seen a single volume of Les cités obscures before. I am definitely going to check these out quite soon. The idea of parallel worlds accessible by common architectural features is something I’ve encountered elsewhere (e.g. the disputed C.S. Lewis fragment The Dark Tower) and I’ve always liked that concept.

Re: The Fifth Head of Cerberus, I suppose that one possible factor in its lack of recognition at the time of its publication is that the original novella was quickly expanded into novel length by the addition of two additional stories and perhaps this caused confusion?

Has anyone brought up Wolfe’s fantasy-future Book of the New Sun, wherein the main character (Severin– very Masoch) is an apprentice torurer who shows mercy, and is exiled to eventually return as king? This brand of conservatism is also known, as it is for Tolkien, as Christianity. Not that there’s one monolithic strain– I memorably read a progressive theology blog that dismissed Chestertonian neo-Distributist orthodoxy as something like “anarcho-syndicalism of the Shire”– but there is a tension between cosmic hierarchy and earthly hierarchy (to the extent that one is seen as an inversion of the other) that could certainly upset the distinctions between “conservative” and “progressive,” with good fantasy writing as a possible avenue of imaginary social engineering.

Book of the New Sun was my introduction to Wolfe and I’ve read it several times as well as the follow-up Long Sun/Short Sun series. The narrator is actually called Severian, but perhaps that’s close enough to still make your point.

Re “Jailers Hate Escapism: Epic Fantasy as Subversive Literature”: a richly realized and nuanced essay; splendid!

————————

Sarah Shoker says:

It’s saddening that a medieval text is potentially more progressive than some modern fans who shout down calls for diverse representation. Two Moorish knights were members of the Round Table and, lest we forget, the Green Knight was actually green skinned in early versions of the tale. But here again, we have an erroneous view of the medieval period as disconnected from the rest of the world.

————————

I’m currently reading David Denby’s “Great Books”…

————————

David Denby, New York city movie critic and journalist, entered Columbia University in 1991 to take the university’s famous course in “Great Books.” This is the course that, in preserving the notion of the western canon without apology to multiculturalists and feminists, has been an unlikely focus of America’s culture war in recent years. Where other universities have caved in and revised or enlarged the canon, Columbia’s course has remained intact…

————————

http://www.amazon.com/GREAT-BOOKS-David-Denby/dp/0684835339

While pointing out that many feminist/left-wing criticisms of that “western canon” are valid, nonetheless he details how many miss the point, or distort the texts. Fail to see how rather than coming across as triumphalist propaganda, hegemonic patriarchal antecedents of Western Colonialism, the ancient Greeks in Homer come across as a savages, a barbaric Other; how conflicted rather than cocksure they are, how bittersweet their victories; how Sophocles’ Oedipus shows that “Not only are we not in control of our lives, our very drive for control can undermine us.”

————————

pallas says:

“To paraphrase Terry Prachett, jailers hate escapism.”

…Michael Moorcock’s rebuttal is great:

“Jailers love escapism. What they hate is escape.”

…Patting yourself on the back because you read “escapist” fantasy stories is a really dubious thing to do.

—————————

Well, aren’t the different kinds of “escapism”? Consider some definitions of the term, gathered at http://www.thefreedictionary.com/escapism:

—————————

The tendency to escape from daily reality or routine by indulging in daydreaming, fantasy, or entertainment.

—————————–

the avoidance of reality by absorption of the mind in entertainment or in an imaginative situation or activity.

—————————–

And…

——————————

the art or technique of escaping from chains, locked trunks, etc., as a form of entertainment. — escapist, n., adj.

——————————

…!

Suppose one is living in a dictatorship or jailed, perhaps trapped in an abusive relationship or soul-killing job; your power to physically leave is either nonexistent or severely curtailed. Various forms of escapism are available:

– One can retain a degree of sanity by escaping into mental realms of the imagination.

– One can indulge in fantasies which go along with and reinforce the existing order. (Say, a poor, oppressed laborer wishing to be rich and to then oppress others; a youth from the ghetto dreaming of bling, women, and being a badass.) In short, the utter opposite of what was a crime in olden England, “Imagining the King’s death.”

– One can imagine a different life for oneself; the steps to take to achieve this, how good it would feel to be free, in a loving relationship, etc. Or, how a more just society could be built. On a more down-to-earth plane, how one’s jailers might be tricked, a crucial key procured.

——————————-

I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which “Escape” is now so often used: a tone for which the uses of the word outside literary criticism give no warrant at all. In what the misusers are fond of calling Real Life, Escape is evidently as a rule very practical, and may even be heroic. … Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls.

– JRR Tolkien, from “On Fairy-Stories”

——————————-

http://www.thetolkienforum.com/showthread.php?14749-Escapism

Or, even is one is not so trapped, what about indulging in “escapist” entertainment for “decompressing” from a day’s utterly worthy work? Is that “dubious” too?

And isn’t this idea that not facing Reality (as if it’s not a multifaceted phenomenon) squarely on, constantly, the better for your nose not to leave contact with the grindstone, awfully limiting? This looking down upon “escapism” in general all too reminiscent of Mencken’s comments:

———————————

The Anglo-Saxon mind… is essentially moral in cut; it is believing, certain, indignant…

The American…casts up all ponderable values, including even the values of beauty, in terms of right and wrong. He is beyond all things else, a judge and a policeman…

———————————-

From that Tolkien site above:

“Keep the company of those who are seeking truth, but run from those who have found it.”

– Vaclav Havel

There’s a great little piece on the Still Eating Oranges blog which, deploying quotes from On Fairy Stories, argues for a valuation of fantasy fiction as a method of perceptual resuscitation.

‘ According to Tolkien, we feel in everyday life a jaded ownership of those things familiar to us. The world becomes mundane: without surprise and beneath our experiential notice. However, as he writes, “Spring is, of course, not really less beautiful because we have seen or heard of other like events”. Events that are to us uninteresting are to others “the first ever seen and recognized”. Spring’s explosive beauty never leaves; but our egos suppress its “fluency”, in Cage’s words. ‘

…

‘ But what type of depiction allows spring to be spring again? Tolkien argues that it is fantasy. By this, one should not understand him to mean the use of orcs and elves. Tolkien writes that fantasy at its most basic is the depiction of something “not actually present”—something not enclosed by “the domination of observed fact”. For just this reason, it reminds us that “observed fact” cannot encircle the alien Otherness of our world. ‘

…

‘ By depicting the “not actually present”, we subvert the illusion that we have seen it all—that we are the all-knowing possessors of the world around us. We are reminded that “all [we] had (or knew) was dangerous and potent, not really effectively chained, free and wild”. The “arresting strangeness” of fantasy breaches the walls of ironic detachment that we have built around ourselves, which have given us the comfort of experiential death. And it is for this reason that the fantastical and exaggerated have been put away in modern times. As Tolkien says, “Many people dislike being ‘arrested’.” Experiential works have been relegated to children and teenagers; and adults, when they pay attention at all, approach only as disinterested analyzers of subtext. ‘

http://stilleatingoranges.tumblr.com/post/47827086914/toward-an-experiential-art

Thanks; those are fascinating and telling perceptions!

And there certainly are agendas for pushing the putting away of the “fantastical and exaggerated”…

This is a very interesting and pertinent article for me. Though I’m very liberal politically I find such “liberal” critique of fantasy as a “conservative” genre that Mieville and Moorcock offer to be extremely myopic and irritating, precisely because it clumsily politicizes something that by its very nature shouldn’t be clumsily politicized.

If I had to state the problem more elegantly I would say that fantasy is Dionysian/Romantic by nature and corrupt Romanticism (Romanticism unmoderated by Humanism and fueled by suppressed hysteria) inevitably becomes Fascism (because Romanticism hinges in way on a desire to experience pain and conflict, to quote Lermontov: “what is a poet’s soul without turmoil and what is ocean without storms?”). This is as much as it has to do with politics. But that doesn’t invalidate Romanticism, because to deny it would be to deny any emotional catharsis based on pain and that would just lead to a horrible, sterile, oppressive sanctimoniousness (which is what so repulses me about the “liberal” critique of fantasy).

I think that as long as we keep and develop a strong sense of individual conscience and moral responsibility (the Appollonian to balance the Dionysian) we can happily be Romantic without falling into Fascism. As funny as it may sound, everyone has a right to his own suffering and his own heroism, in fact, when that right is taken away is precisely the time when Fascism and Militarism rear their ugly heads, because they come to fill an emotional void that is usually not being recognized and understood well enough. The societies that became Fascist are precisely the societies that lived comfortably enough to desire conflict for spiritual catharsis (to balance out the comfort) and not self aware enough to recognize that need and deal with it through art and sports (that’s the reason why we have fantasy like WarHammer and why some fascists see it as emblematic and attractive, but the point for the existence of wargames (and sports too) is precisely so we won’t have to act our militaristic tendencies on a political arena).

Tolkien’s wide and enduring success by the way is precisely because he married the two sides, the Humanistic and the Romantic (the Christian and the Pagan) in one story, and not because of some political agenda (liberal or conservative).

In short, as long as we stay responsible and aware of such problems as “conflict of duties”, as long as we stay moral AND allow for moral complexity (which in the end is more interesting and challenging than any militaristic conflict, and satisfies the human need for challenge and ov

*continued from the comment above*

In short, as long as we stay responsible and aware of such problems as “conflict of duties”, as long as we stay moral AND allow for moral complexity (which in the end is more interesting and challenging than any militaristic conflict, and satisfies the human need for challenge and overcoming much more fully, so guys like Nietzsche would be happy too), we should be alright, we needn’t worry about the “conservativeness” of Fantasy, it’s there to provide flavour and excitement to life, not to serve a political agenda.