Stop me if you’ve heard this one before:

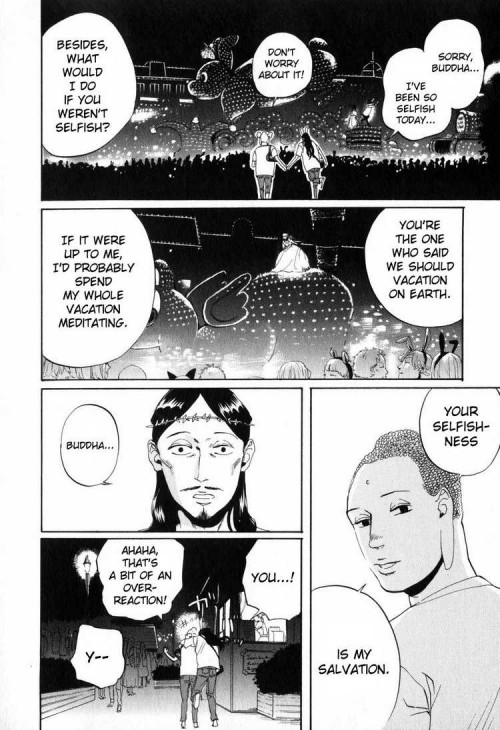

Jesus and Buddha are best friends vacationing on earth incognito, in a cheap apartment in Japan.

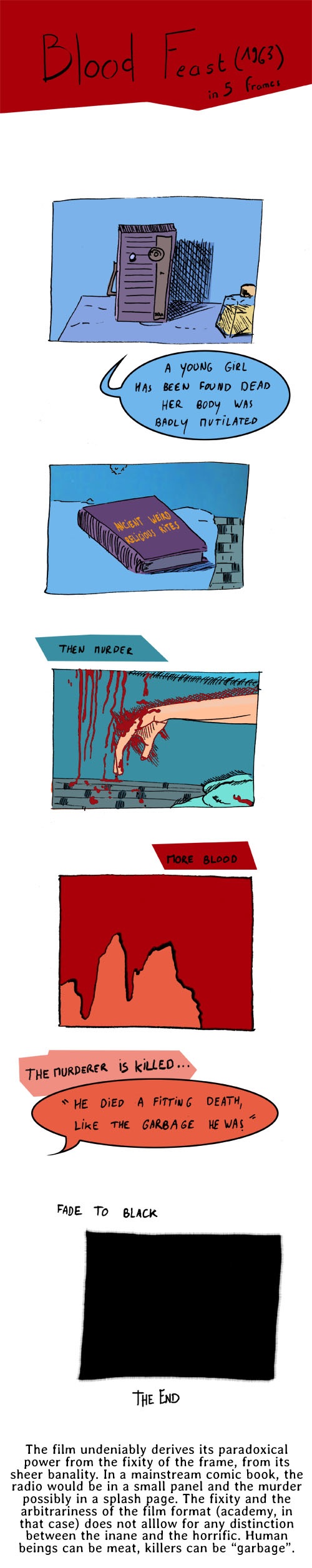

Thanks to the scanlation team for all translations and images

That’s the basic premise and entire joke behind Saint Young Men, a Japanese comic written and drawn by Hikaru Nakamura, serialized by Kodansha and recently adapted into an anime (although not licensed in the US). While kicking back on Earth, the two “young” men live ordinary lives as unemployed twenty-somethings in the Tokyo neighborhood equivalent of Brooklyn Bed-Stuy. They worry about making rent, try to hide their employment status from their landlady and their celestial status from everyone else, attend local festivals and – very rarely – take trips outside their neighborhood. They might have esoteric worries (when Buddha is too agitated, he glows with an otherworldly light; when Jesus is too agitated, his crown of thorns starts to bleed), but for the most part they have the same worries as the rest of us.

They have the same worries, but with the ultimate out: to quote Jarvis Cocker, “When you’re laid in bed at night watching roaches climb the wall/If you call your Dad he could stop it all”.

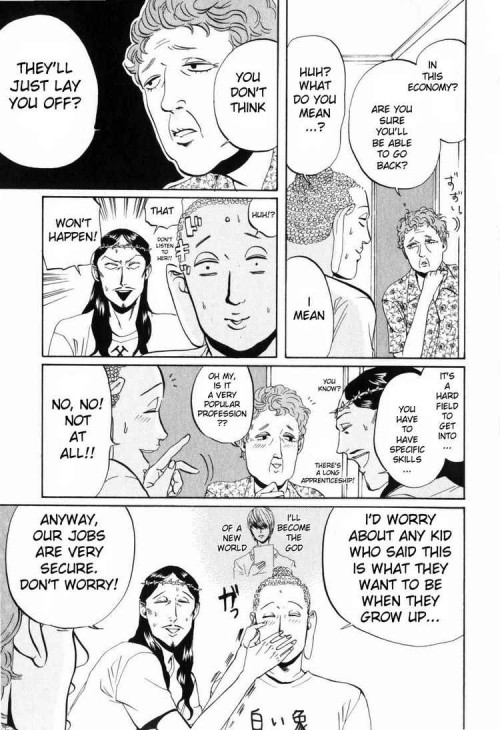

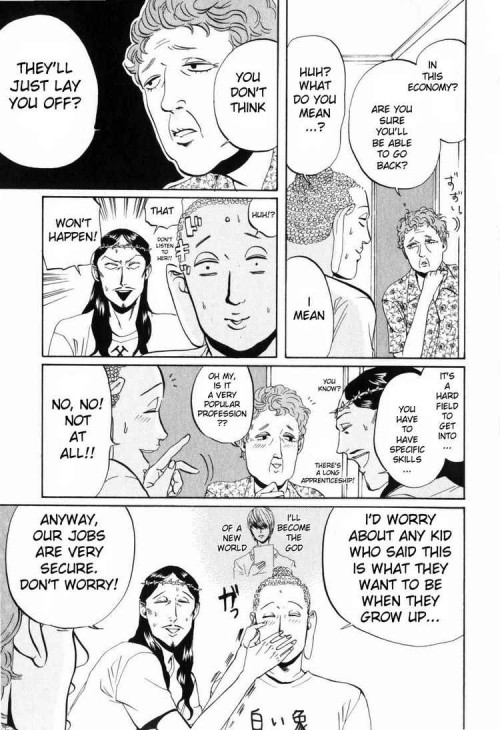

Why the Gods don’t worry about employment security

In fact, even the Saints’ worries about rent money are of the privileged sort: Jesus has a tendency to impulse-buy expensive frivolities online; Buddha, normally the pragmatic and rational half of their odd couple, can be similarly swayed out of fondness for Jesus or by fancy cooking equipment. The comic doesn’t tell us where the Saints are getting their money from, or what they do to resolve these situations – Wire to Heaven for extra cash? Take part-time jobs? – but in general this is a gentle, humorous comic, free of desperate situations and/or depressing current events. The Gods have seen the Earth – at least one neighborhood of it in Tokyo – and declared it is Good.

Indeed, when money gets tight, Buddha can meditate and Jesus can transmute stones into bread, eliminating the need for a food budget:

The monetary benefits of an aesthetic lifestyle

The premise of this series — that if these particular holy men lived on Earth in the present day, they’d be hipsters/herbivore men — is charming and makes a lot of sense. Think on Jesus’ stance against moneylenders, or Buddha’s transcendence of material desire, and the conclusions draw themselves. Even beyond moral(?) arguments, though, it’s easy to see that the two live comfortable lives as slackers on Earth. That’s because they have chosen a life of frugality and under-employment, not been forced into it by a lack of other options. As celestial beings, they avoid the tribulations of the precariat.

A taxonomy of Japanese freeter – portmanteau of “freelance” and “labourer” which also has connotations of “freedom from the onerous demands of full-time employment” – includes a distinction between those who choose to work and spend less, and those who have no choice. Jesus and Buddha fall squarely into the first category, choosing not to take on full-time jobs even though they are available, thus leaving more time for hobbies and relaxation.

Indeed, they are perfect candidates for the happily-underachieving stereotype: as God’s only son, Jesus is the ultimate trustifarian; as an aesthetic who has strong connections with nature, Buddha is perfectly adapted to the slow living, under-consuming lifestyle.

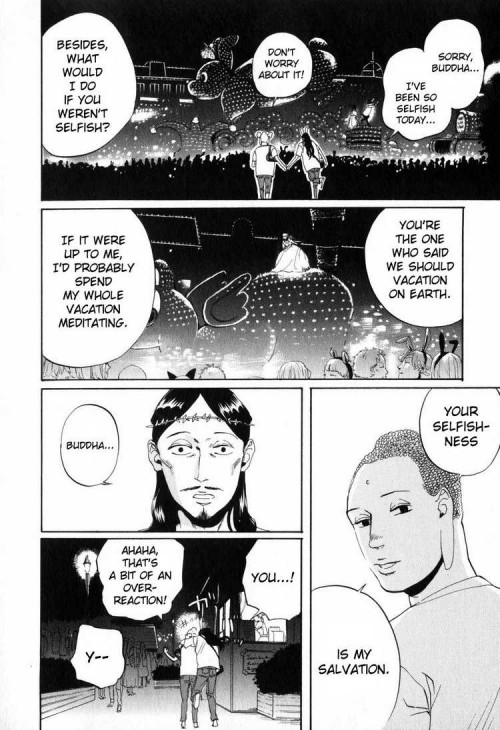

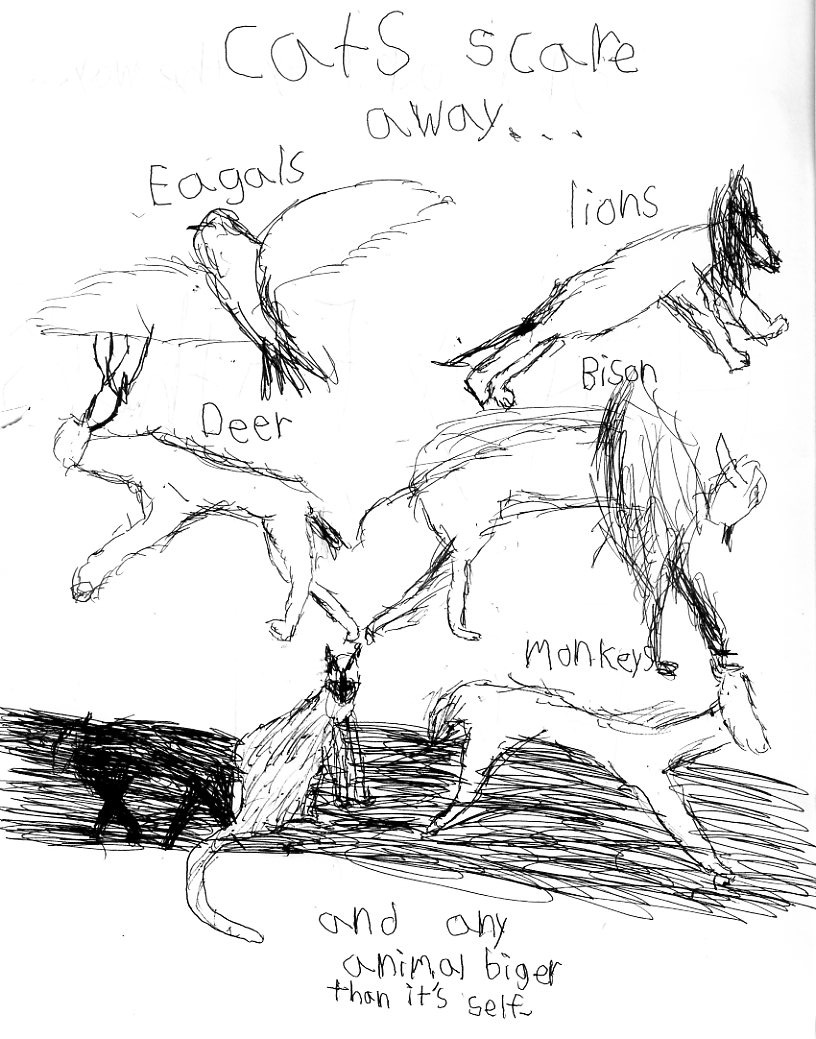

In fact, if Buddha were in charge of this manga they’d never consume anything at all. Also: awwwww.

Does it really make sense to lump those who choose to have leisure from those who are denied full-time work? Over at Neojaponisme, evolving discussion of freeter will ring true to anyone who has been following parallel developments in talk about Williamsburg Hipsters(TM):

Freeter are only freeter if their parents were white collar employees. Kids from poor families who become convenience store clerks are just “poor.” So, this “fun” of being in the lower classes — the holidays! the beef bowls! — is praising a false kind of poverty where kids know their parents can bail them out if the hairstylist gig can’t pay for the insurance bills. Rest assured, freeter will be authentically poor in about ten to twenty years, but right now, they aren’t so much “lower class and lovin’ it” as enjoying the ride down the socioeconomic fun slide.

-From Japan discovers poor people, and they are awesome, December 2005

According to a 2003 survey, 70% of freeters would happily take a full-time white collar job if offered one. So, they’re not exactly ideological rebels — just simply “unemployable.” This other 30%, however, may be the proto-bohemians that everyone from “Slow Life”-advocates to David Brooks-followers are searching for. But if you’ve ever seen the lifestyle of workers in Japan’s hipster cultural industry, you’ll notice that even without the dark suits and cherei morning exercises, these “cool kids” have just replicated the work-style and values of the salaryman life within the magazine/music making process: long hours and expectations of total-dedication to the job.

-From A No-Tenko Japanese Youth, May 2005

The happiness factor is the interesting twist to this rise in class consciousness. Middle-class kids are indeed dropping out of the rigid employment system, living a comfortable, inexpensive lifestyle, and identifying themselves as “lower class,” but they are far from angry about their diminished position… But here’s where my perverse sense of conspiratorial over-analysis kicks in: The future structure of global capitalism needs fewer and fewer people to actually man the posts at the white-collar firms, and this will result in an overwhelmingly large amount of people kicked out of the economic system. In the United States, the lower classes are angrier and angrier about their loss of stature and respectable employment, and while they may not be channeling their anger into the right places (Down with Gay Cowboys!), no one is actually happy to work at McDonalds to support their punk band. In Japan, they have found the perfect solution to the natural bifurcation of labor in 21st century capitalism. The trade offs for money are so high that you have a large section of population voluntarily dropping out and feeling relieved to be out of the rat race. Perhaps this “happiness” of the lower classes is only a myth to protect the hegemony, but at the worm’s eye view, the story seems to check out. Everyone wins: The system no longer has to pay the masses decent wages, and the masses feel lucky to have so much free time.

-From The Rise of Social Class in Japan, Part 1.5, January 2006

Kids these days are not even “up to no good” — just up to very, very little. I never thought I would ever see grown-ups pulling their hair over the fact that kids aren’t smoking and drinking enough. They don’t have a new and mysterious pharmacopeia of illicit drugs. (How naïve and unaware is this article on the current “rise” of amphetamines in Japan, as if speed was not the single government-condoned way to get high for the last 50 years.) Japanese youth aren’t having crazy orgies, and you hear less about strings of “sex friends.” Their preferred style of music is the highly-formulaic seishun punk and ska (or judging from declining music sales, silence). Youth are obsessed with “feel good” banter with friends, the act of communicating on phones without much emphasis on the content and building fragile communities of electronically-mediated acquaintances. They are not even destructive — just retracting into their shells and failing to report for the single pre-determined path into the social hierarchy.

-From The Kids Are All Wrong, January 2008

I have bolded a section in the second quote, above, about employment at “cool” companies because I feel it also matches expectations for how the Saint Young Men ought to act when they are on the job: being celestial might be the ultimate alternate career path, but when these guys are working, they work all the time. After all, what could be more full-time than 24/7 across all time and space?

Even when they’re not working, they’re still working

I’ve bolded a section in the third quote, above, about the American working-class poor for reasons I will discuss at the end of the article. In the meantime, speaking of cross-national comparisons: the term NEET (Not in Education, Employment or Training) originated in the UK, but has spread to Japan, South Korea, and China, reflecting realities of globalized labor in which more people compete for less work. The result – obviously in Japan, and less obviously in other places – is a split of the job market into a core of stable, well compensated jobs with stringent entry requirements; and a larger set of precarious, dangerous, dead-end, boring, unpleasant, and/or badly compensated work.

NEET, famously, has negative connotations – these are people who have removed themselves from a competitive environment. As they don’t compete, they can never succeed. Jesus and Buddha don’t belong in this category – they have already succeeded at founding major world religions! – so when the series opens they are only taking what is, explicitly in the comic, a well-earned break from their jobs (says Jesus to Buddha: “We’ve been working too much – we ended up being busy with the end of the Millennium, and all”). They don’t quite fit the analysis, in other words. That’s understandable: all of the economic and cultural critique I’m quoting is a bit heavy for a low-stakes slice of life comedy.

Nevertheless, if I can be allowed to extrapolate: the fact that these two holy beings are essentially bumming around surely lends moral weight to the position that there’s nothing wrong with bumming around. Or, as Neojaponisme has it: “Saint Young Men follows the adventures of divine slackers Jesus and Buddha, taking a well deserved break from the holy. Scenes of school girls mistaking Jesus for Johnny Depp set the tone, and the series continues as a silly and laid back paean to everyday routine. As decline narratives proliferate inside and outside Japan, [this series offers] a charming look at the rich patchwork of plebian culture that Japan can still count on.”

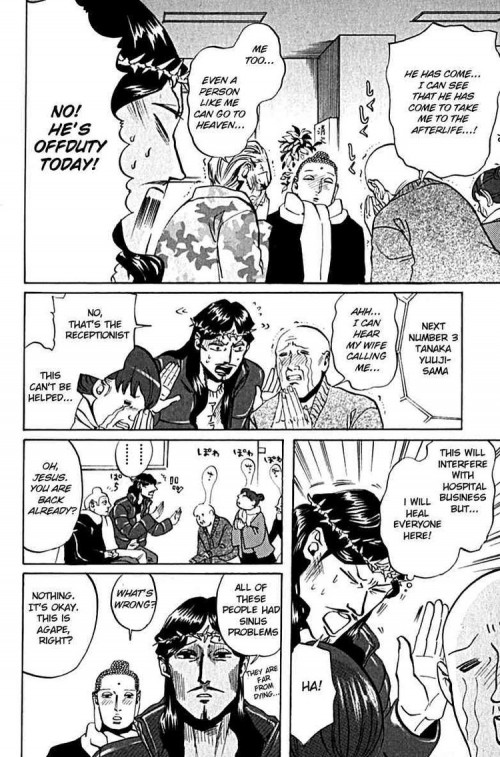

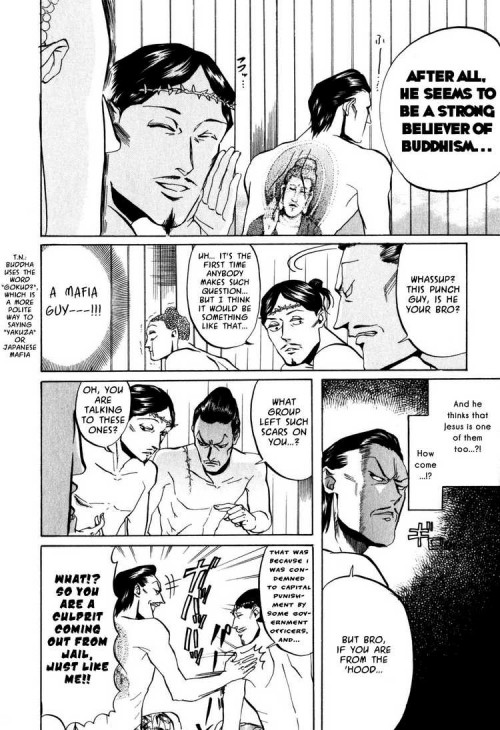

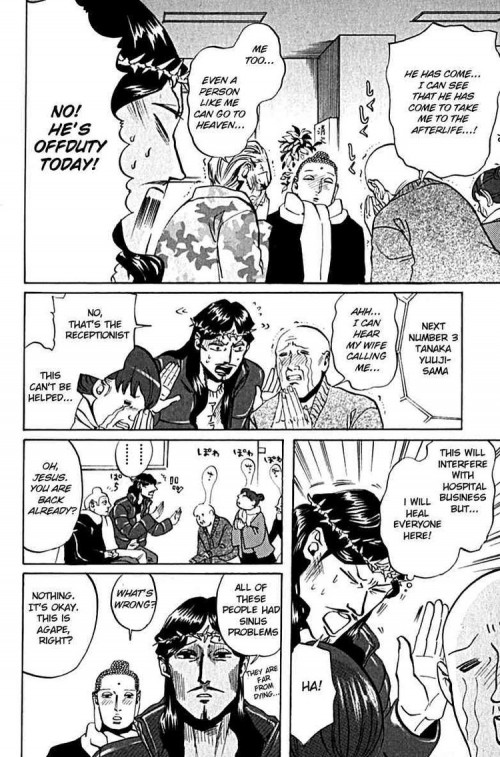

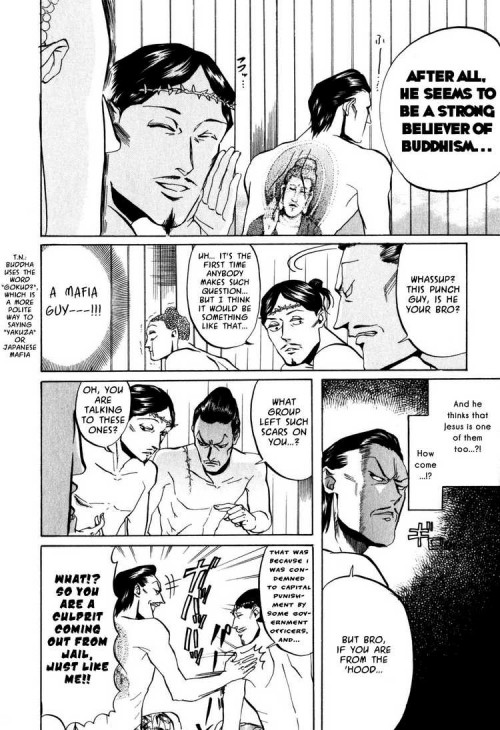

Kicking it with local mafia at a local public bath: a humorous take on Japanese plebian culture

Now that we’ve established that this is a gentle, humorous comic that touches on modern economic conditions without making a big deal out of them – centered around the general premise What if God was one of us?/Just a slob like one of us?/Forced to squeeze onto an overly crowded subway car like one of us? – it’s time to evaluate Saint Young Men on what can really be the only determinant of success or failure on the comic’s own terms.

Is it funny?

A pun on “Hottoke” (= leave me alone) and “Hotoke” (= Buddha) which I’m sure you’ll all agree is hysterical…

The comic takes a while to find itself. It seems that for the first couple chapters, the premise is the thing: the mere fact of Jesus and Buddha on Earth, being Japanese freeter together, is thought to be hilarious enough in its own right. No religious knowledge is required to understand the simple jokes in these chapters, which is surely a goal of the author; on the flipside, the jokes aren’t very funny, even on a “dumb slapstick” level. The beginning of the comic focuses on simple humor based around the Saints’ appearance (Buddha looks like a Buddha statue! Jesus has long hair!) and puns on their names. Even if you happen to like puns, it’s clear that more than one panel dedicated to setting up these jokes is more than one panel too many; pun-humor is later — and more appropriately — relegated to “ironic” homemade silk-screened t-shirts (and how hipster is that?).

In these early chapters, Saint Young Men feels less like a comic about Jesus and the Buddha and more like a comic about two characters who happen to resemble the most common physical representations of Jesus and the Buddha and to share their names, in other words.

Although, admittedly, the series premise does take you pretty far.

Fortunately, the comic improves: in keeping with the series premise of Jesus and the Buddha as voluntary freeter, their formerly cardboard characters are brought to life when the author takes the time to develop their personalities, preferences, and probably most importantly…hobbies.

So without further ado:

MEET THE SAINT YOUNG MEN: JESUS

Jesus is a sweet-natured, compassionate, impulsive and irresponsible character. He has a personality like a puppy’s, always caught up in the enthusiasm of the moment. Confronted with obvious suffering, he always wants to help; confronted with a Shinsengumi cosplay or fancy new laptop, he always wants to buy it. Jesus does no cooking or cleaning, but contributes in his own way to the comic, usually suggesting all of their outings and livening up the atmosphere.

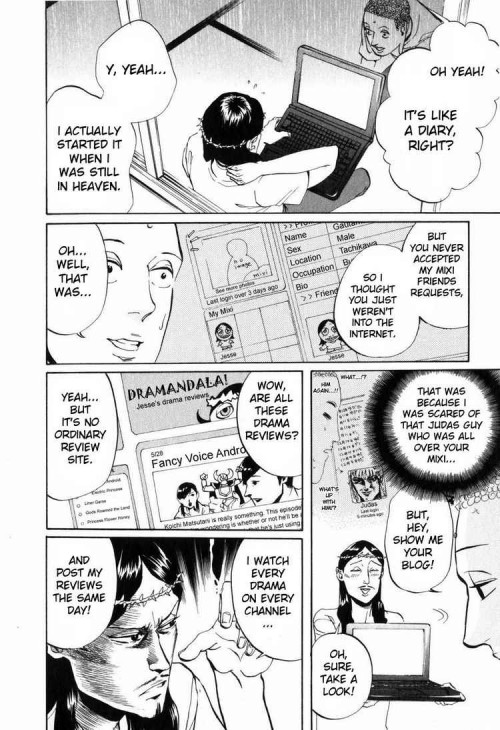

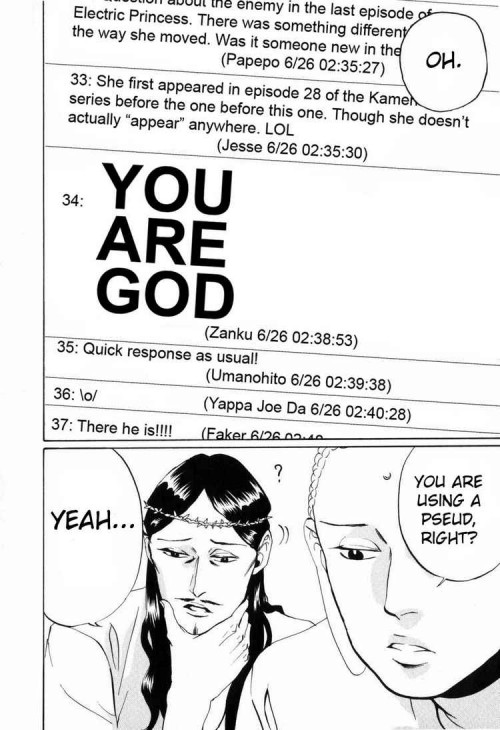

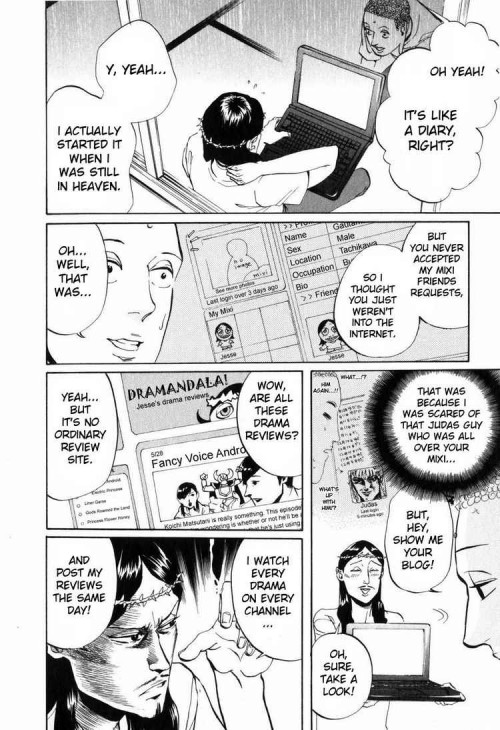

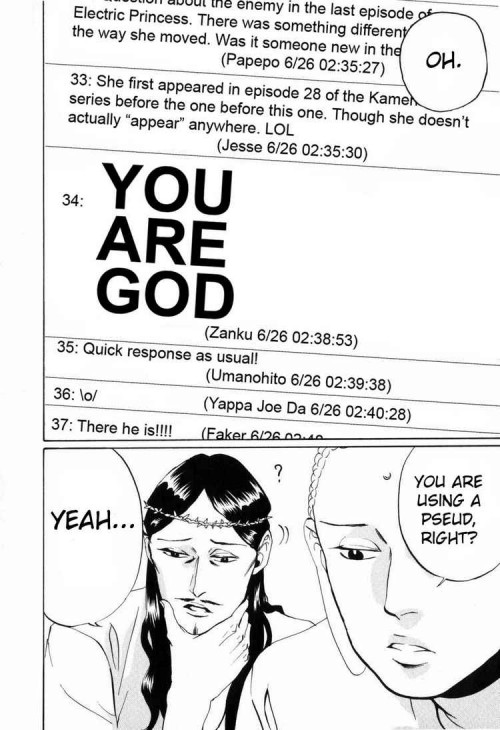

Also, he’s a dedicated blogger who immediately turns to the internet following each of the pair’s adventures, mining all of their experiences for material for his online diary. In fact, it was Jesus’s friends online who first convinced him that it would be fun to live on earth for a while.

Jesus, the blogging and Japanese drama addict

MEET THE SAINT YOUNG MEN: THE BUDDHA

The Buddha is the more outwardly serious character here. He enjoys meditation, gardening, cooking, and cleaning. He is responsible, generally, for the household budget and for vetoing Jesus’s impulse spending. In one of the funnier mini-arcs of the manga, Jesus and Buddha make a pilgrimage to the holy land – I mean Akibhara, the electronics capital of Japan, of course – where Jesus excitedly anticipates a new laptop or smart phone, only to learn that Buddha has something far more domestic in mind: a new, state-of-the-art rice cooker.

The dynamic works well, but if the Hotoke Buddha were only the straight man to Jesus’s gag man, the series would be unfair to Buddhists. So Buddha has quirks, too: for one, he’s unexpectedly sensitive about his appearance. Much like you would feel if you were constantly confronted with unflattering pictures of yourself after you’d gained weight following a bad breakup, the Buddha would prefer a world where sculptors liked his chubby phase less. He also wishes he could, just once, be treated badly by an animal – as a change from all the times his life has resembled a scene from the Disney version of Snow White.

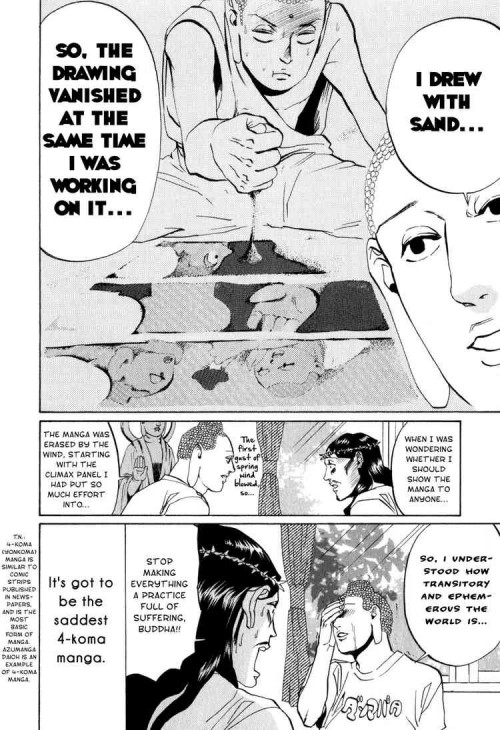

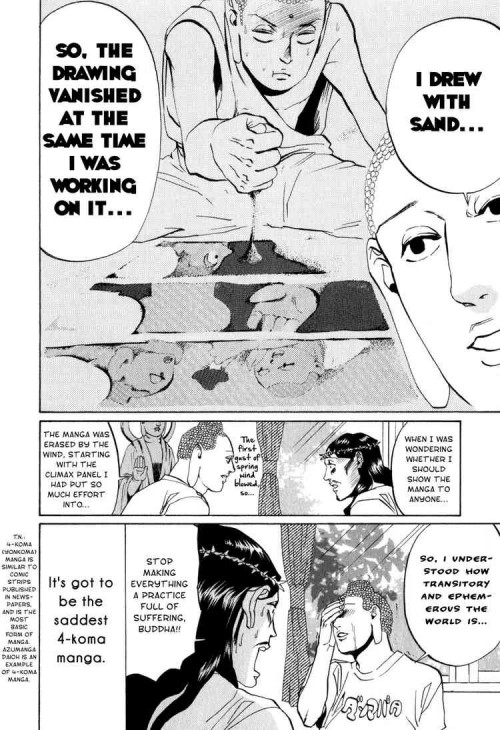

Oh, and inspired by the classic Tezuma manga “Buddha”, he draws manga.

I mean really draws, not just draws with sand; although a sand mandala comic is pretty funny. See also “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bonseki

Probably appropriately for a nominally Buddhist country, the Buddha is the more serious character here; but it’s hard to argue with the author’s comic-yet-sympathetic take on Jesus and his Guardian Angels. (Or at least that’s how I personally feel, speaking as an atheist Jew.) Jesus is a silly character, but not a malicious one; overall the comic is non-controversial.

Actually, Saint Young Men’s approach — avoid controversy by focusing on well-known stories and inventing new personalities — reminds me of Hetalia: Axis Powers more than anything else — a more compassionate and less slapstick version.

Finally, the comic has local color. Saint Young Men could be set anywhere, but it is definitely set in a Tokyo neighborhood. Going all the way back to that section I bolded, above, about the American working poor, one notable thing about Japan as compared to America is that it has a well-established low-income culture. There are lots of things you can do in public in Japan that are free or don’t cost very much money. Local festivals. Shopping for bargains at traditional markets — or just looking. Free public parks and trails that are reachable by foot. Local public baths and shrines, and manga-and-video rental cafes that don’t have time limits on how long you can stay.

The grass is always greener, and there are plenty of advantages to being poor in the US, like cheaper mass-media (movies, music, video games) and food, including fresh fruit and sit-down fast food. But generally Japan, like the UK and parts of Europe, is a place where you can meaningfully belong even if you aren’t able to buy your way into the dominant consumer culture.

Or maybe that’s not true at all, and is part of the reason people turn to the Internet for social meaning. Also, LOL.

Saying that, I’ll end this essay with my version of Saint Young Men set in New York (Brooklyn Bed-Stuy):

-Jesus and Buddha have a rent-subsidized apartment in the East Village; when their lease runs out, they are unable to find another apartment in their budget and wind up moving to Brooklyn, where Jesus has online friends thanks to his TV-show review blog.

-In Brooklyn, Buddha joins a coop network of local rooftop gardeners who all exchange recipes and fresh ingredients

-Jesus branches out from TV reviews to food writing, highlighting Buddha’s recipes in months when the budget is too tight for them to eat out

-Jesus indulges in his love of cosplay by attending many themed costume parties. His most popular costume is of course Johnny Depp from Pirates of the Carribbean.

-When Buddha is concerned about his appearance, Jesus suggests that they both lose weight by signing up to work as bike messengers. This works until Jesus is hit by a car; Buddha narrowly manages to convince the entire cohort of Angels not to descend on earth blowing trumpets heralding the apocalypse. The pair realize they don’t have health insurance. Fortunately the accident isn’t serious and Jesus recovers on this own.

-Jesus enjoys attending weekly bar showings of popular television dramas.

-Jesus and Buddha enjoy local parades such as the Irish Parade, the Italian Parade, and the Pueto Rican parade; and picnicking in local parks. However, they avoid big parks like Central Park and Prospect park because the animals there congregate around Buddha.

-Buddha does not become a manga-ka but appreciates art “events” like subway graffiti or the sand paintings in Washington Square Park. He mostly sticks to the “art” of cooking.

-Everyone assumes that Jesus is in a band and he eventually buys a second-hand guitar and half-heartedly tries to learn. He gives up pretty quickly but Buddha takes an interest and masters ukulele.

-Jesus gets a part-time job with Midtown Comics, but is too laid-back about it and is eventually let go. All the customers miss him, though, so he’s rehired (but decides he’d rather have time to watch TV shows).

And so on; really this stuff writes itself.