The lovely and talented Patrick Carland is joining us as a regular blogger. Welcome aboard Patrick!

On HU

I talk about the smaller-than-life soul of Womack and Womack.

Voices from the Archive: Marc Singer on morality in All-Star Superman.

Jones, One of the Jones Boys explains why all the superpowers have to be dull.

Chris Gavaler on Man of Steel, eugenics, and why do DC films have to be so dour anyway?

I did an extended analysis of the father’s day card my son made me. Because it’s my blog, damn it.

Subdee on Saint Young Men and divinities as boho slackers.

Patrick Carland on the Hunger Games, Battle Royale, and neoliberalism putting children to the scythe.

Utilitarians Everywhere

I wrote about:

The Dan Clowes show at the Chicago MCA for the Chicago Reader.

Being a man trapped by the male gaze for the Good Men Project.

A doc about a gay couple and their 8 weddings for the Atlantic.

And for Splice Today:

The Scorpions’ first album was fucking awesome.

Why reading doesn’t make you more human.

Edward Snowden, Russia, and thuggish bullies.

Other Links

Tom Spurgeon with a magnificent, endless, amazing obituary for Kim Thompson.

Janet Potter on the Ladydrawers show in Chicago.

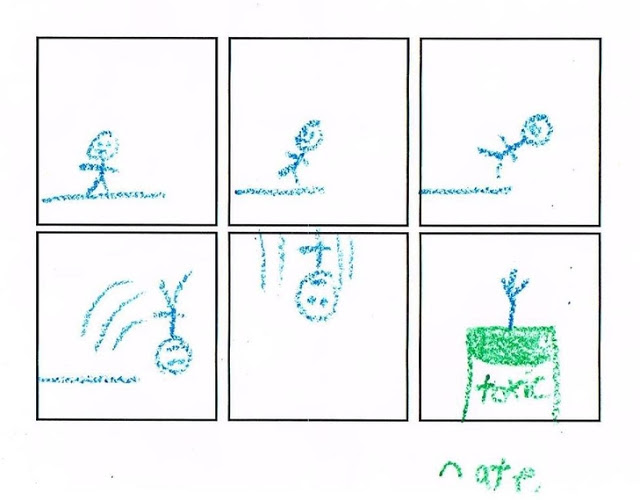

Jeffry O. Gustafson analyzes a kid’s comic about some stick figure falling into a vat of toxic waste.

Ben Schwartz with a sweet tribute to Kim Thompson.

Jonathan Bernstein on Wendy Davis and why talking fillibusters are still a bad idea in the Senate.

a propos reading: at the (generally horrible) NYTimes philosophy blog, Greg Currie recently expressed scepticism about similar ideas, but from a different direction, viz. that there’s actual no evidence for the reader’s self-flattering claim that reading literature makes us better. Post here.

There’s a whole fanservice genre of literature about how totally awesome you are for reading, so much better than those stupid clods who don’t read — Farenheit 451, those Jasper Fforde books…those kinds of books drive me up the wall.

Actually, he seems to say that there’s very little evidence either way. Indeed, it is Currie’s willingness to acknowledge the empirical limitations on both sides of the argument — while digging into what that evidence might look like, and why we might expect to find or not find it — that makes this essay so refreshing to read.

(I particularly like his handy dismissal of the dismal “If X is supposed to contribute to Y, then why can I come with this counterexample Z” rebuttal.)

But I do share your hatred to the ubiquitous joys-of-reading-powers-of-the-imagination chorus (particularly in children’s and YA books).

Fahrenheit 451 is noxious.

I’m kind of skeptical of his claims about empirical evidence in this sort of area, I have to say. If we don’t trust literature (which I don’t think we should) it’s not clear to me why we should trust psychology, the claims of which to scientific status arguably make it less reliable, not more.

For example, he says this:

“Suppose a schools inspector reported on the efficacy of our education system by listing ways that teachers might be helping students to learn; the inspector would be out of a job pretty soon.”

As far as I can tell, we really have limited ability to measure the efficacy of our education system, and trying is mostly used as an excuse to harass teachers and institute miserable testing regimes. If education research is our gold standard for investigating the moral claims of literature, we might as well give up.

I agree, Noah, but since he was talking about the empirical claims (and presuppositions) of the proponents of reading great literature, I think it’s more than fair. That said, it does not close the matter, just continues the argument.

Yeah, that’s reasonable. It’s certainly worth pointing out that the claims for literature as morally improving are built on nothing.

Just after reading your comments, I came across this awful 4-paragraph botching of aesthetic and scientific claims — within a list of the “Greatest Ideas in Science,” no less!

I’m reminded of a history book on the origin of human rights, individualism and all those other enlightenment ills (I kid) reviewed in class.

Anyway, I don’t remember the name of the book or the author but she seemed to attribute this in part to the newly popular novel. The assumption being that it allowed the educated upper classes to empathize with people of a different stature, this peek into their inner life confirming that they too might be human. I don’t know if this theory was based on something other than contemporaneity but it’s certainly the most forceful argument for the importance of literature I’ve heard of, even though I remain skeptical.

I would say that your skepticism seems very much warranted.

Ormur,

I think you’re recalling Stephen Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature — a strong and well-documented book, by even its critics’ reckoning as far as I recall. There is a relatively small section that addresses the novel, amid a series of possible explanatory causal scenarios for declining violence rates over the centuries (“The Humanitarian Revolution”).

Here is a relevant extract.

Oops. “Steven.”

Hmmm…that sounds right. It also fits with my sense that Pinker’s book could be nickled and dimed to death; he often doesn’t quite seem to know what he’s talking about on specifics.

I wrote about it here.

In the hands of a *good* teacher, practically anything from playing with playdough to reading books to playing on jungle gyms can make people better (for various definitions of better). And the same is true of self directed study. People can find spirituality and compassion, or problem solving skills, or whatever, in staring at ponds or going to bars or surfing or making ugly crafts. Or reading books. The same people doing those activities without the right attitude can come away without that stuff. Or with different takeaways. That’s humans for you.

Education research is somewhat complicated. It’s one of the fields where some (American!) journals are peer reviewed and others are not. (I come from a background where, well, why the hell would you have a journal and NOT peer review it? That’s stupid.)

But even so, there is plenty of good research on teaching. It even makes most (good) teachers plenty happy, and it has nothing to do with testing. The research all basically says the same thing. To get good results, you need: small classes (not 30 kids, by the way, but 10, 15, even 5), you need well-paid and high-status and well-trained and well-taught teachers (like the rest of the advanced world does, ahem–ever wonder why many Asian schools have such good math results? the teacher generally know about ten ways to teach each math topic, and customize the explanation to the student, whereas in America, many math teachers know only way and force all students to use that because they have limited options or forced curricula), you need reasonably good facilities and materials (like a book per kid, etc), and the children need sensible levels of social/familial/physical support. For instance, kids do better if they have a safe home environment, caring parents, regular meals, etc.

This is perfectly straightforward, well-researched, well-supported. It’s just fucking expensive. America really hates paying anything to do with kids, so.

even by HU standards, this:

“If we don’t trust literature […] it’s not clear to me why we should trust psychology”

is a very silly syllogism. Compare: if I don’t believe astrology can predict the future, I shouldn’t believe that the Pythagorean theorem can predict the length of hypotenuses.

So…you’re saying that psychology is comparable to geometry? Because that seems to be how people often want to treat it, and it also seems significantly sillier than my original comparison.

Literature and psychology both are said to provide insight into the human psyche, and the human moral experience. I really don’t see much evidence that psychology is better at that than literature. Which is to say, they can both be somewhat good at it, depending, but not in an especially rationalized or scientific way. As far as I can tell.

Psychology was pretty good at proving the problems with the whole language method.

Also, I don’t know about literature in particular (I’m skeptical that it’s of no more value than watching daytime TV), but writing has helped develop thought and our understanding of the world around us immensely. It’d be pretty dumb to deny that. Maybe there’s been a few illiterate scientists, but I can’t think of one. And it’s certainly a very small percentage.

You mean the whole language method of reading? The way I taught my son to read before he went to school? Without any problem at all?

I don’t know that anyone would deny that writing is a useful technology. The combustion engine is also a useful technology. Not clear that either of them makes us better people, though.

So, in your opinion, what *does* make us “better” people? Good parenting and childhood environment? After which you’re set for life?

In my opinion? I really don’t know. I mean — that’s kind of one of those key-to-the-universe questions, right? If I knew that I should probably be attempting to organize a social movement rather than editing a blog.

I find Stanley Hauerwas convincing when he argues that for individuals to be good, you need good communities. But how you make good communities doesn’t really seem any easier than how you make good individuals, so…

I wouldn’t even really say that I know how to be a good person myself, much less lay down general rules for how everybody else can be good.

Peter, I’m pretty sure it wasn’t Pinker, he might have gotten that argument from this book though, it was by a historian I probably should know but not anyone with a high profile outside of the field.

But literature, doesn’t it at least offer the chance to empathize with people different from yourself or those you mingle with? I can see how that could make someone a better person, no guarantees of course.

The argument about empathy is pretty common. I don’t think there’s necessarily a link between empathizing with someone in a book and empathizing with someone in real life, though.

“You mean the whole language method of reading? The way I taught my son to read before he went to school? Without any problem at all? ”

This is silly… Sure, whole language will work with some kids (how about kids with intelligent parents and a culture of reading?)…but it has proven to be a disaster for many/most without those benefits. It took about 10 minutes to teach my elder daughter to read, but it’s pretty foolish to think that it’s similarly easy for all kids. Phonics is a very helpful tool…and been proven over and over that phonics and whole language combined is the most effective means of teaching kids to read for most people.

The Pinker argument (as labeled above anyway) is humorously opposed by Terry Eagleton who notes that “empathy” is not always something that is good for people. Most “canonical” literature (he suggests) encourages you to empathize with the ruling classes, and thus you’ll be less likely to revolt against them or oppose their ideology. I’m not sure this is true, but it’s a good corrective to mushy Romantic idolizing of the powers of literature to make us empathize (perhaps most forcefully expressed by Percy Shelley in his “Defence of Poetry”

close parentheses

“Phonics is a very helpful tool…and been proven over and over that phonics and whole language combined is the most effective means of teaching kids to read for most people.”

That seems rather different from Charles’ suggestion above that whole language doesn’t work, yes? Instead, it suggests that whole language is part of an effective teaching strategy.

Though…again, it obviously varies quite a bit from individual to individual. Which is why psychology is a fairly dicey excuse for a science. These aren’t reproducible experiments here.

Depends on what you mean by whole language — as it was originally opposed and implemented for years, it was at the expense to phoneme-to-grapheme training. That was a miserable failure, and proven so by psychological research. If you mean phonics with a concern for context, reading enjoyment, individual learning styles (none of which was ever in actual opposition to phonemic training), then that’s not really the whole language approach. Anyway, the better Berlatsky is correct.

But I didn’t use phonics with my son…so it seems pretty clear that using phonics is not always necessary (I tried to get him to sound words out occasionally, actually, but he just ignored me.)

There’s quite a bit of statistical regularity among human traits and activities. I don’t much feel like arguing with you again on this quite obviously true statement, but I figured I’d go ahead and state it once more for HU’s posterity.

Okay, I don’t know how well your son spells (you admitted to being a poor speller once, I believe) or reads. Just fine, I guess, but no one said “necessary,” so statistically …

My son reads avidly and quite far above grade level, thanks, and he spells fine for a ninth grader as far as I can tell.

And sure, statistics can tell you things. Using statistics to make arguments about classroom methods seems fine, as long as you’ve got a teacher there who can adjust for individuals when inevitably some of them don’t fit the statistical pattern. Using statistics to make sweeping generalizations about human nature seems like a problem, though, since people who don’t fit are then assumed to have something wrong with them (which is sort of where you went when you kind of sort of suggested my son couldn’t spell, right?)

Sigh, can we not discuss your private experience? I wasn’t suggesting anything about your family whatsoever other than no one but you has any way of knowing.

Statistically speaking, your experience doesn’t fit a good deal many cases. But who cares? Using statistics to find generalizable truths is bad, but using your own private experience (a sample size of 1) is just fine. Some real solid reasoning there.

Also, how do you know what grade level reading ability is without statistics?

The original discussion was about whether reading makes you more human, or tells you universal human truths. I said it did not, and that I didn’t think psychology did either.

You responded by saying that psychology tells us about the best method of reading. I said that it doesn’t appear to be the best method for everyone, and that generalizing from “statistically better” to “universal human truth” (the original terms of the argument) is a bad idea.

Okay? I’m not rejecting statistics. I’m just saying that using psychology to make statements about human nature needs to include the same kind of caveats you would use if you were claiming that literature tells you about universal human nature.

I understand the analogy that you are making and that I probably agree with you, but let me present a Reecesque case for why Psychology could be thought of in a way such that your analogy was inappropriate.

1. If we can make sense of the phrase “universal truths about human (psychological) nature” it will be saying something about the frequency of discernible psychological traits in the group of individuals we would conceptually consider humans.

2. Insofar as those traits exist (in all humans), they are conceptually evaluable. That is, we can identify them as having a proper application.

3. Psychology, understood as a scientific discipline, purports to identify statistical trends in these conceptually evaluable psychological traits of human beings. If there were such a thing as a universal human psychological trait, Psychology could, in principle, capture it (by saying it has 100% occurrence rate in the population of individuals that we have already called humans).

4. (Much of) Literature makes no such (explicit) claim to a scientifically unanimous criterion (we are only concerned with these disciplines insofar as they have a stated aim so that we can identify whether or not they fulfill the criterion they have set out for themselves, insofar as that criterion can be conceptually evaluated, and the aims of literature are various.) Therefore, they are disanalogous.

In short, Psychology is predicated on the idea that we have agreed ahead of time on the proper conceptual application for a given trait. A caveat is built into its structure. Literature, on the other hand, has no such limitation.

Hey Owen. That seems reasonable. It’s not always clear whether psychologies pretensions to science make it better or worse as a conceptual system than literature, though.

By what criteria of better or worse? Do you mean morally?

Hmmm. Well, I’d say both potentially morally and perhaps in terms of accuracy, in some sense. There have been some fairly crappy things done in the name of psychology. Literature tends not to quite have the same biopower leverage since it isn’t tied into discourses of medicine and science. You can write a homophobic poem, but it doesn’t have the same practical impact as writing homophobia into your psychological definitions. At least not these days (things were probably somewhat different in the past.)

That is a difficult set of assertions to wrap my brain around. I think that Psychology, encompassing Psychopathology and Psychopharmacology, can and has been used for some very good things despite its troubled history.

Similarly, Literature has had a past that is difficult to morally evaluate in any simple way.

In terms of accuracy, it depends entirely upon the case which we are considering.

I’m not saying it hasn’t. I just think there’s a tendency to rationalize the less savory bits as errors on the way to greater progress, or as somebody else’s accidents.

Statistics? Fooey — psychology has the certainty of geometry

I want to see you reproduce the human mind with a compass and a protractor, damn it….

Ha, I’ll accept that, Owen.

I think Noah has in mind psychoanalysis and the like when he says, “psychology.” I instead think of models and experimental research concerning memory, perception, attention, etc., cognitive and neuro- science, even behaviorism. I’m alright with it not being called a hard science, but it requires more than literature to be considered valid. Literature isn’t going to dismissed just because what it says is fiction. That’s why psychoanalysis isn’t anything more than literature and why it’s not practiced in psychology departments. I’m glad that Noah puts no more trust in the objectivity of stuff like the male gaze than he would a Star Wars novel (I await “Being a Man Trapped by the Patriarchal Force”).

Star Wars novels can tell us things. And…I’ve written extensively about how I don’t necessarily agree with Mulvey’s male gaze. Like, thousands and thousands of words about it. And a piece linked in this review, for that matter.

And, no, I’m not just talking about psychoanalysis. Lots of psych seems like bullshit, not least because of its pretensions to science (which psychoanalysis suffered from too.) Evolutionary psychology is the fairy tale of our time.

Do you have a problem with Evolutionary Psychology in principle or in popular discourse? I can imagine scenarios, based on the statistical vision of Psychology sketched above, where the statistics would suggest that our best tentative hypothetical explanation for a given phenomenon would involve an evolutionary story.

Mostly popular discourse…though a lot of that popular discourse is based on research and assumptions that seem fairly ridiculous to me.

I’m not a fan of the “just so” theories of evolutionary psychology, either. (There are plenty of interesting theories and good research that connects human behavior and thinking to biology, though.) But note that you’re actually dismissing something with “evolutionary psychology is the fairy tale of our time,” but not so much with “literature is the fairy tale of our time.” Literature doesn’t have to be any more objectively valid than a fairy tale, whereas evolutionary psychology does.

I mean, literature just isn’t constrained by the caveats of verifiability, falsifiability, reliability and validity in the way psychology is.

That’s absolutely correct. But what I’m saying is, literature doesn’t make any pretense to that sort of verifiability. That’s more honest, or more truthful, I think, than evpsych’s just so stories, which claim to be telling us scientifically what really happened.

But it’s not a pretense of verifiability if one can reject a psychological theory on the grounds that it doesn’t pass it as a criterion.

But can one? How do you verify evpsych stuff? It’s all tautological, and you can’t rerun evolution and check. The experiments and conclusions are all built on chains of really dicey leaps and assumptions. Slotting it under “science” often seems more about giving rhetorical force to dicey claims than about actually presenting something that can be debunked in any sort of straightforward, or even circuitous, way.

How can you verify any evolutionary claim? Generally, you have to make predictions consistent with your theory or model and test to see if they hold.

It’s tricky. But it’s a lot easier to verify biological claims through experiment and looking at the fossil record than to make claims about human psychology. It’s not entirely clear that you can actually verify the latter kind of claim, given the massive amounts we don’t know about the human brain, and the even more massive limitations on our knowledge re nature/nurture. Therefore, attempting to claim some sort of verifiability for evpsych seems really tendentious…and more about claiming science’s juju than about actually doing something that looks much like science.

But scientists don’t need to make expansive claims in some Evo Psych cases. Imagine a scenario where an evo psychologist observes statistical trends, makes an evolutionary hypothesis and accompanying predictions, and the predictions are confirmed (statistically). It seems like they don’t need the sort of momentous knowledge of our existential status in order to do that sort of work. They simply need to make a falsifiable hypothesis that is either confirmed or disconfirmed by the available data. It seems as though we should reasonably consider this a plausible hypothesis with the sort of pragmatic and scientific skepticism that should accompany critical assessment of good scientific theories.

Sure, that seems fine. I just haven’t seen many such narrow-claims-with-caveats reported in that way.

I don’t know; if you’ve got an example of good evpsych work, feel free to mention it. The stuff I see always seems to be along the lines of “men are from mars, women are from venus, because our ancestors had ape genitals.”

Hey Noah, are you equally skeptical about sociology’s, social psychology’s, and social determinism’s “just so” stories?

That said, there certainly is a problem with the way that Ev Psych (and science in general) is reported. But that isn’t always the fault of the science.

If you are interested in a good overview of the field, I’d suggest Jaime Conifer (et al.)’s “Evolutionary Psychology: Controversies, Questions, Prospects, and Limitations,” downloadable here.

Peter, pretty much on all those counts.

I’d say that separating out the fault of the science vs. the journalism is often trickier than people like to think? There just seem to be a lot of evpsych folks who are obsessed with men from mars etc. narratives.

Some evpsych scientist recently was quoted as saying that fat people shouldn’t be allowed into grad school because they clearly didn’t have the self-control necessary to succeed. That’s just one asshole, obviously, but still.

Oh, dear, hadn’t heard of that one. Looks like it was a Tweet, which he tried to take down: “Dear obese PhD applicants: if you didn’t have the willpower to stop eating carbs, you won’t have the willpower to do a dissertation #truth.” The controversy even has it’s own section on his Wiki page!

Good grief; I didn’t even consider that the whole thing might be archived and easily searchable. The web is an amazing thing….

“Debating” Noah on “science” is like “debating” Richard Dawkins on “religion”, in more ways than one.

Still: is the evidence for psychological hypotheses indirect? Do various research programs in psychology rely on assumptions which might turn out to be false? Is the “knowledge” thereby accrued defeasible? Are there sociological and institutional biases that skew the research? Are there serious flaws with some of the research? Is the research often presented in the public arena in a simple-minded and misleading way? Do the scientists themselves sometimes misrepresent the research? Is the history of psychology, in part, a history of false starts, dead ends, hype, and overall dunder-headedness? In short, is it hard to do psychology properly?

Answers, respectively: yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes and yes. Welcome to science. (Or, if you prefer, “science”).

Also, for the record: yes, they do shit in the woods, he is a Catholic, and it’s Grant that’s buried there. And, with that, I’ll go back to biting my tongue.

Science has done a lot of beneficial things. It’s a beautiful and amazing thing in a lot of ways. Does Dawkins ever say that sort of thing about religion? Maybe he does and I just haven’t seen it….

Anyway… you believe that psychology or, say, economics, is every bit as solid a science as math or physics?

I really don’t think that pointing out that evpsych is kind of a boondoggle is necessarily the same thing as calling all of science into question. It’s not even teh same thing as calling evolution into question. I mean, I like Feyerabend, and I’m not above questioning physics, but as a system for making truth claims, it’s just a lot more solid than psychology or economics, both of which are social sciences with pretensions, for the most part.

Also…has your opinion of me nose-dived recently, Jones? Shoes too tight? You just seem a good bit crankier than usual these last couple weeks….

ha ha, maybe. maybe it’s because i’ve been getting up at 5 (in the middle of winter, no less) to go jogging.

anyway, i do agree with your third paragraph. there is good evolutionary psychology, but it’s often not the stuff that percolates into non-specialist domains. and there is good psychological research (apart from general evolutionary considerations) that’s pretty solid

http://photos1.blogger.com/blogger/5088/629/1600/calvin_oatmeal.jpg

to be fair, middle of winter in Sydney is way less awful than in most of the US

I guess it’s true that “whole language” technically means “not using phonics”–or chunks of words, or sounding out, etc. But…nobody is telling us to “sound out” every word we encounter. Standard training is to have a “big bank” of words we basically learn/memorize (“word walls” in most elementary schools), but that it’s useful to know why/how these words are pronounced in this way, so that, when encountering new words, we can figure out how to pronounce them…and even (by seeing them as made up of smaller sounds/words), having a decent shot at figuring out what they mean (also with context, of course). The latter part is “phonics”–which “whole language” basically advocates rejecting altogether. The total rejection of phonics was once a popular educational movement. It was pretty much a disaster.

Studies indicate that you need to have a big bank of words you “know”–but phonics is also helpful/important since we’re constantly encountering words we’ve never seen before. Of course, effectiveness in teaching phonics (or whole language reading for that matter) varies from classroom to classroom (and student to student). This seems pretty much “common sense”–but, of course, common sense is rarely observed/followed without much wrangling and expensive research.

The single biggest indicators of whether kids learn to read effectively has nothing to do with school at all (no surprise). Do their parents have books in the home? Do parents read to the child? If the answers to these questions are “yes,” kids learn to read easily and quickly. If not…it’s a struggle…but phonics do usually help matters.