I’ve avoided reading We3 for years, in part because I find depictions of violence against animals upsetting, and I was afraid I’d find it painful to read.

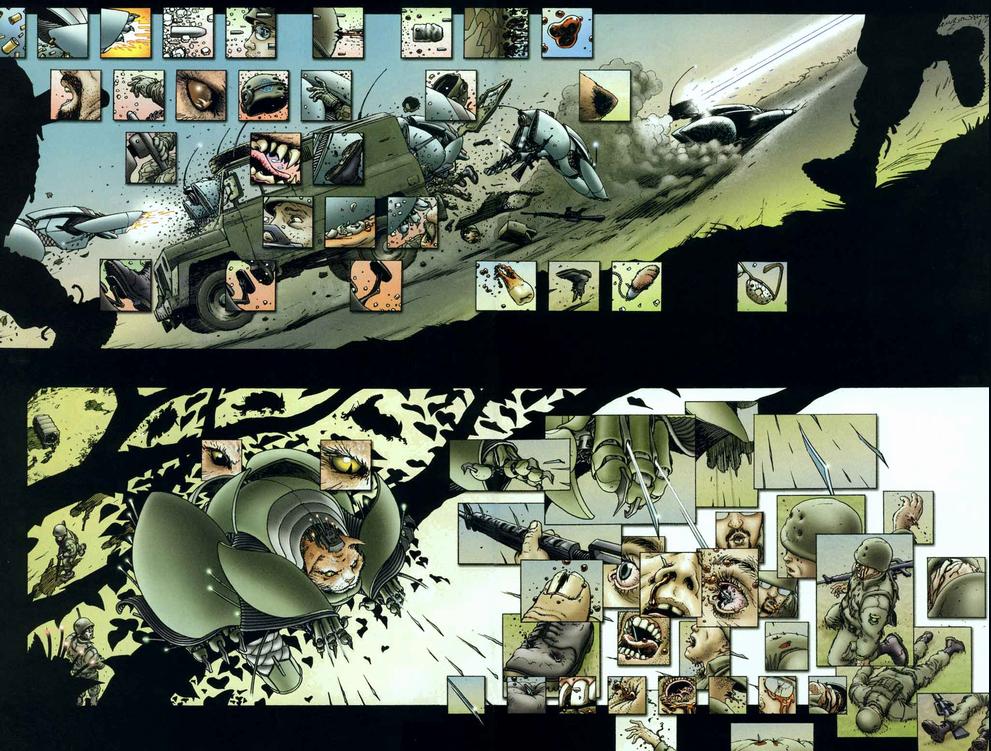

As it turns out, though, I needn’t have worried. We3 does have some heart-tugging moments for animal-lovers — but they’re safely buried and distanced by the towering pile of bone-headed standard-issue action movie tropes. There’s the hard-assed military assholes, the scientist-with-a-conscience, the bum with a heart of gold and an anti-fascist streak…and of course the cannon-fodder. Lots and lots of cannon fodder. We3 clearly wants to be about the cruelty of animal testing and, relatedly, about the evils of violence — themes which Morrison covered, with some subtlety and grace, back in his classic run on Animal Man. In We3, though, he and Frank Quitely gets distracted by the pro-forma need to check the body-count boxes.

The plot is just the standard rogue supersoldiers fight their evil handlers. The only innovation is that the supersoldiers are dogs and cats and bunnies. That does change the dynamic marginally; you get more sentiment and less testosterone. But the basic conventions are still in place, which means that the comic is still mostly about an escalating series of violent confrontations more or less for their own sake. It’s hard to really take much of a coherent stand against violence and cruelty when so much of your genre commitments and emotional energy are going into showing how cool your deadly bio-engineered cyborg killer cat is. To underline the idiocy of the whole thing, Morrison has us walked through the entire comic by various military observers acting as a greek chorus/audience stand-in to tell us how horrifying/awesome it is to be watching all of this violence/pathos. You can see him and Frank Quitely sitting down together and saying, “Wait! what if the plot isn’t quite thoroughly predictable enough?! What if the Superguy fans experience a seizure when they can’t hear the grinding of the narrative gears?! Better through in some boring dudes explicating; that always works.”

The point here isn’t that convention is always and everywhere bad. Rather, the point is that conventions have their own logic and inertia, and if you want to say something different with them, you need to think about it fairly carefully.

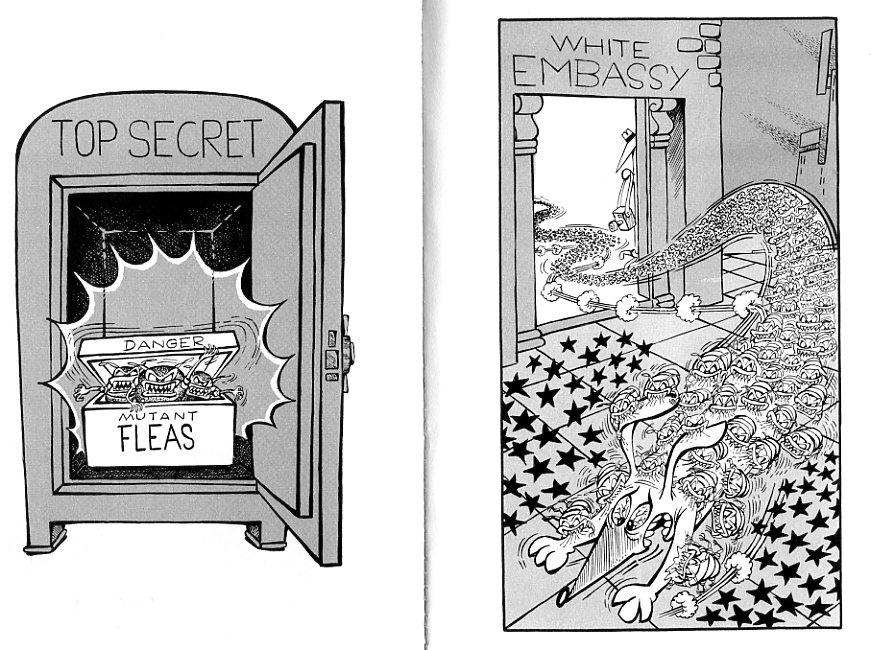

Antonio Prohias’ Spy vs. Spy comics, for example, are every bit as conventional as We3, both in the sense that they use established tropes (the zany animated slapstick violence of Warner Bros. and Tom and Jerry), and in the sense that they’re almost ritualized — to the point where in the collection Missions of Madness, Prohias is careful to alternate between black spy victory and white spy victory in an iron and ludicrous display of even-handedness. Moreover, Spy vs. Spy, like We3, is, at least to some extent, trying to say something about violence with these tropes — in this case, specifically about the Cold War.

Obviously, a lot of the fun of Spy vs. Spy is watching the hyperbolic and inventive methods of sneakiness and destruction…the black spy’s extended (and ultimately tragic) training as a dog to infiltrate white headquarters, or the white spy’s extended efforts to dig into black HQ…only to end up (through improbable mechanisms of earth removal) back in his own vault. But the very elaborateness and silliness of the conventions, and their predictable repetition, functions as a (light-hearted) parody. Prohias’ spies are not cool and sexy and competent and victorious, like James Bond. Rather, they’re ludicrous, each committing huge amounts of ingenuity, cleverness, malice, and resources to a never-ending orgy of spite. Spy vs. Spy is certainly committed to its genre pleasures and slapstick, but those genre pleasures don’t contradict its (lightly held, but visible) thematic content. Reading We3, you feel like someone tried to stuff a nature documentary into Robocop and didn’t bother to work out how to make the joints fit. Spy vs. Spy, on the other hand, is never anything less than immaculately constructed.

We3 doesn’t seem to realize its themes and conventions don’t fit; Spy vs. Spy gets the two to sync. That leaves one other option when dealing with genre and violence, which is to try to deliberately push against your tropes. Which is, I think, what happens in Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs.

Martyr’s is an extremely controversial film. Charles Reece expresses something of a critical consensus when he refers to it as “really depressing shit.”

And yet, why is Martyr’s so depressing…or, for that matter, why is it shit? Many fewer people die in Martyr’s than in We3; there are fewer acts of violence than in Spy vs. Spy. Even the film’s horrific finale — in which the main character is flayed alive — is hardly new (I first saw it in an Alan Moore Swamp Thing comic, myself.) So why have so many reviewers reacted as if this is something especially shocking or especially depressing?

I think the reason is that Laugier is very smart about how he deploys violence, and about how he deploys genre tropes. Violence, even in horror, generally functions in very specific ways. Often, for example, violence in horror exists in the context of revenge; it builds and builds and then there is a cathartic reversal by the hero or final girl.

Laugier goes out of his way to frustrate those expectations. The film is in some sense a rape/revenge; it starts with a young girl, Lucie, who is tortured; she escapes and some years later seeks vengeance on her abusers.

But Laughier does not allow us to feel the usual satisfying meaty thump of violence perpetrated and repaid. We don’t see any of the torture to Lucie; the film starts after she escapes. As a result, we don’t know who did what to her…and when she tracks down the people who she says are the perpetrators, we don’t know whether to believe her. As a result, we don’t get the rush of revenge. Instead, we see our putative protagonist perform a cold-blooded, motiveless murder of a normal middle-class family, including their high-school age kids.

We do find out later that the mother and father (though not their children) were the abusers…but by that time the emotional moment is lost. We don’t get to feel the revenge. On the contrary, no sooner have we realized that they deserved it, than we swing back over to the rape. Lucie has already killed herself, but Anna, her friend, is captured and thrown into a dungeon, taking her former companion’s place. There she is tortured by an ordinary looking couple who look much like the couple Lucie killed. Thus, instead of rape/revenge, we get the revenge with no rape, and the rape with no revenge. Violence is not regulated by justice or narrative convention; it just exists as trauma with no resolution.

I wouldn’t say that Martyrs is a perfect film, or a work of genius, or anything like that. Anna’s torture is done in the name of making a martyr of her; the torturers believe suffering will give her secret knowledge. And, as Charles point out, they end up being right — Anna does attain some sort of transcendence, a resolution which seems to justify the cruelty. And then there’s the inevitable final, stupid plot twist, when the only person who hears Anna explain her secret knowledge goes off into the bathroom and shoots herself. So no one will ever know what Anna saw, get it? Presumably this is supposed to be clever, but really it mostly feels like the filmmakers steered themselves into a narrative dead end and didn’t know how to get out.

Still, I think Charles is a bit harsh when he says that the film is meaninglessly monotonous, that it is not transgressive, and that the only thing it has to offer is to make the viewer wonder “can I endure this? can I justify my willingness to endure this?” Or, to put it another way, I think making people ask those questions is interesting and perhaps worthwhile in itself. It’s not easy to make violence onscreen feel unpleasant; it’s not easy to make people react to it like there’s something wrong with it. Even Charles’ demand that the film’s violence provide transgression — doesn’t that structurally put him on the side of the torturers (and arguably ultimately the filmmakers), who want trauma to create meaning?

Charles especially dislikes the handling of the high-school kids who are killed by Lucie. He argues that they are presented as innocent, because their lifestyle is never linked to their parents’ actions. Anna’s torture is mundane enough and monotonous enough to recall real atrocities, and conjure up real political torture — basically, a guy just walks up to her and starts hitting her. But the evocation of third-world regimes, or even of America’s torture regimen, no matter how skillfully referenced, falls flat since it is is not brought home to the bourgeois naifs who live atop the abattoir.

Again, though, I think the disconnection, which seems deliberate, is in some ways a strength of the film, rather than a weakness. Violence isn’t rationalized or conventionally justified in Martyrs — except by the bad guys, who are pretty clearly insane. In a more standard slasher like Hostel, everyone is guilty,and everyone is punished. In Martyrs, though, you don’t get the satisfaction of seeing everyone get theirs, because scrambling the genre tropes makes the brutality unintelligible. The conventions that are supposed to allow us to make sense of the trauma don’t function in Martyrs — which makes it clear how much we want violence to speak in a voice we can understand.

“A voice we can uderstand” indeed– language is the thing that keeps violence (physical, but also the violence in other areas, like language) at a distance. Violence is an inchoate form of self-propagating reactive pleasure, and the only morally aware way to deal with it, I think, involves some short-circuiting of the pleasure that language allows violence to impart.

I haven’t seen “Martyr,” but your description of how frustrates the rape-revenge fantasy narrative puts me in mind of the movie “Irreversible.” It’s a deeply problematic movie, (it features a graphic, 15 minute depiction of a rape that I skipped… thank god for DVD), but it’s really relentless in its effort to undermine the Charles Bronson “Death Wish” genre.

The movie goes backwards in time, beginning with the revenge scene, which because it lacks context looks pretty much like a straightforward murder… It then moves back in 10 or 15 minute increments in the style of “Momento,” and it becomes clear that the murder is indeed a revenge killing for the protracted rape scene, which happens roughly half-way through the story. The movie then continues to move back, and ends earlier that day, when the rape victim is reading in the park, just having a normal day. There’s no catharsis, just a really unsettled feeling and the sense that you participated in something you shouldn’t have.

Anyway, while its overall success is arguable, it isn’t for lack of trying. The director works hard to play with the form as a way to undermine its logic (or lack thereof).

Huh…that sounds fascinating Nate. Thanks for mentioning it; I will keep my eye out for that film.

And yes, it does sound a lot like Martyrs.

Hmm, I haven’t seen Irreversible in ages but wasn’t the person killed in the opening scene an innocent – a case of mistaken identity. So it’s more like an anti-rape/revenge movie (the futility of justice both temporal and divine etc).

There’s a (political) point to Martyrs as that essay Charles linked to suggests.

I think I prefer the elliptical narrative of Martyrs to something like Incendies (which got top marks by critics). That one also puts the heroine through some psychological horrors but is a bit more obvious in its intent (to me anyway).

I think Charles’ argument that the obvious political point doesn’t quite work is more or less on target. As a screed against the complacent bourgeoisie it’s got problems. It’s smarter about refusing to follow through on the conventions of violence, I think.

I recall it being the actual person, but I checked the Wiki and it turns out Suat is correct. My memory of the movie is a little off kilter since I went into not knowing what to expect, and finished it not knowing quite what to think.

Regarding “Irreversible,” I even believe that the real rapist is shown in the crowd, watching (and smiling?) as the mistaken man is pulped.

[I think that this is an incredible movie — but one that I have never recommended to anyone.]

The ending to Martyrs is truly baffling and bordering on, to borrow Noah’s favorite negative description, evil. It does undermine just about any political and genre points that are made throughout the film. But it’s too late at that point to become a standard horror film that really has a supernatural diegesis. I don’t see how it can’t be seen as justification of, to use its most obvious parallel, the Church’s role in martyring Joan. Religious persecution has an ultimate meaning. Laugier should’ve stayed with materialism. All the relentless brutality in the film (and I’ve not encountered anything to this level in any other film) ultimately doesn’t transgress shit … except for good taste, but I ruined by taste buds a long time ago. I would’ve had the same nausea watching the 15 minute torture scene even if it hadn’t been ultimately justified, but my moral reaction would’ve been different.

The rape in Irreversible is the worst rape scene (meaning the most emotionally effective) I’ve seen. And the reason it’s so horrifying is the reason the torture in Martyrs is so horrifying: the lack of any escape valve, either for the character or the viewer’s emotional reaction (provided one doesn’t fast forward). There’s far more gore and slaughter in films like Dead Alive, but it’s played for laughs. Just like most slashers aren’t taken for anything but entertainment. Laugier reversion to the conventions of horror (or maybe Catholicism — not much of a difference, I suppose) offers the viewer a safe place, but at the expense of everything the film otherwise seems to be saying. Noe, however, does it right: the dialectic of rape and vengeance doesn’t make either any more meaningful. Laugier fills rape (both actual and figuratively) with positive potential, makes it religious. This, to me, is deeply offensive.

It’s not that film is meaninglessly monotonous, but maybe too meaningful. Despite the film’s transgressive intent, it winds up supporting status quo expectations regarding watching a horror film and about what many people are forced to “witness” in the real world. This movie made me feel almost as depressed as Capturing the Friedmans, but the ending turned that depression into exploitation. Salo wouldn’t be the same with an avenging angel or Bronson showing up at the end, you know?

Nevertheless, I do think Laugier has the potential to be one of the more important horror directors. There’s a real sadness to his followup Hollywood film, The Tall Man, with Jessica Biel. It, too, features female martyrdom while defying generic expectations. And much to his credit, his outlook isn’t as amenable to commercial theaters as some of the other current French horror directors. He’s willing to go places others aren’t. I hope the film industry doesn’t stomp that out of him.

Noah:

Trauma in art isn’t the same as trauma in life. Believing art always says something with its use of trauma doesn’t entail a belief that realworld trauma is always filled with purpose and meaning. The former is a commentary on the latter. So, to the degree that Martyrs says something about realworld trauma, the ending suggests a positive virtue to it. This is a pretty common religious belief. It’s how the religion offers hope to the miserable. All your suffering is not for nothing. Contrary to your take on the violence, the film does justify it by making it conventionally meaningful (or, at least, a good portion of the violence — the film isn’t exactly coherent).

I guess my point is that you can also read Martyrs as saying that the desire to use trauma for purpose and meaning is problematic, even as it also seems to want to embrace that. I think it’s a pretty interesting issue to think about. So I appreciate the way the movie tries to do that, and the way it uses/undermines conventions to do that, though I don’t know that it’s entirely successful.

I don’t know that it really makes the case that real world trauma is virtuous either though. It may well be trying to say that, but the end is pretty glib and clumsy. I don’t think it’s too hard to read it against itself, though I’d agree that it’s not necessarily clear that that’s what the filmmakers intend you to do.

Have you changed your mind about the film a little? You sound more positive in the comment than in your review.

Charles: “The ending to Martyrs is truly baffling and bordering on, to borrow Noah’s favorite negative description, evil.”

It’s only evil if you think the victim actually managed to communicate truth to the chief torturer. Since the whole thing is partly meant to be an extended political metaphor, there’s little doubt that the ending is hopelessly optimistic. The idea that one of the oppressors would shoot herself after being apprised of the “truth” of her actions (of life, whatever) is clearly both an open question and taunt to the (guilty, white) audience (basically, go kill yourself).

More likely, you’d end up like Robert McNamara, admitting you did evil but getting a book deal out of it.

Right…the “truth” could be “you are evil and are going to hell,” or some such.

I don’t think it’s all that well done though. Possibly the point is meant to be something like, suffering is or can be redemptive, but the people who inflict the suffering are nonetheless damned. But that’s a subtle and complicated argument, and the twist shock ending isn’t really adequate.

There’s even reason to believe that the “mystery” the victim whispers to the torturer is the film you’re watching (i.e. Martyrs). Basically Pascal Laugier is torturing his audience to get them to understand the “truth.”

I’m not saying this is effective though.

I don’t think what she says to the Mademoiselle is all that important to my description, Suat. I figure the intention is something like “if you had to live through what I’ve seen, Ms. Imperialist, you’d kill yourself.” That, at least, seems like the most parsimonious interpretation. My problem is with the notion that pain and suffering foisted on someone can lead to enlightenment, the discovery of an ultimate truth (not with what the powers-that-be might do with such knowledge once acquired). The movie shows the viewer a whole mindscape trip that does suggest some sort of metaphysical discovery. If Laugier had intended the possibility of no discovery, why include that sequence? As an illusion being witnessed by the girl? If the latter, then the Mademoiselle killing herself seems really off. Mainly because she’s not discovered anything by this process before and didn’t become depressed enough for suicide.

Here’s Laugier’s take:

But I definitely agree that the suicide is a sign of optimism. The supernatural aspect is, to me, a sign of optimism.

Noah, that sounds right enough. Maybe it’s the fact that the film no longer exists as afterimages on my retinae, so I’ve changed my mind a bit. It’s also because I didn’t bother to express my admiration for Laugier’s attempt, but was originally trying to grapple with why this film was so much more troubling to me in how it went wrong than all those exploitation and transgressive films that don’t cause me much of a problem. I just found a copy of the film, so I’m curious to watch it again.

I’ll never be tempted to watch Capturing the Friedmans again, though. That depressed me for days and days. Just felt absolutely miserable. Amazing doc, though.