A couple of years ago, I tried the Black Butler manga, but it didn’t move me. I’d forgotten all about it until a friend recommended the anime to me.

I was stuck at home on doctor’s orders the other day–a day I had planned to be spending in my glorious summertime garden. I was too grumpy to be in the mood for my usual cozy mysteries. Stuck inside on one of summer’s most perfect days? I wanted a little bite with my mindless entertainment. So I gave Black Butler another whirl.

At first, I was both frustrated and bored with what appeared to be a pretty traditional story. Young scion of wealthy aristocratic family has a tragic past. His whole family, mom and dad and even the family dog, died in a great big house fire several years ago. This leaves young Ciel Phantomgrave to be the Phantomgrave at a terribly young age–they don’t say exactly how old, but young enough to wear short-shorts and garters and lace and carry a whip. You know, as you do.

He even has a bad eye covered by an eyepatch. Can you get more stock anime? I felt like I was watching a remake of Godchild/Count Cain, except with bizarre plucky comic relief provided by the other servants in the house (a lecherous maid, a cook, another male servant who often looks like a doll). Ciel, the frilly lace and shorts-wearing scion, had a bit of Count Cain’s caustic wit, so I sighed and continued to watch.

During the first episode, we discover that Ciel makes some kind of terrible bargain while suspended in air and surrounded by feathers, wearing nothing but a sheet. You know, as you do.

The bargain appears to involve his Butler, Sebastian.

That’s also quite similar to the Count Cain/Godchild plot (where Cain is paired with his butler Riff). But, unlike Riff, Sebastian is actually shown butling. Which was strange and kind of funny, if you don’t mind broad humor involving knives, forks, and broken dishes. The regular household staff is both earnest and incompetent. When Ciel has a guest for dinner, the staff manages to screw up the cleaning, cooking, and gardening to such an extent that Sebastian has to step in.

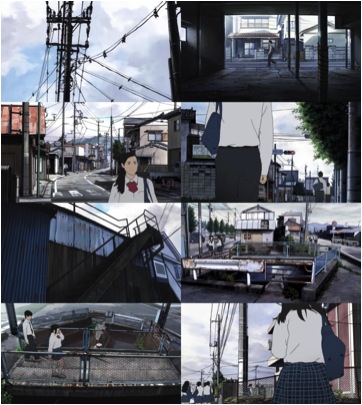

Thus the plucky comic relief when Sebastian serves their foreign guest donuri bowl (actually rare meat Sebastian rescued from the charred mess the cool make) and shows off a traditional rock garden (really gravel raked over the mess the help made of the front lawn). I was starting to think that perhaps Black Butler was a lighter, sillier version of the Count Cain genre.

I kept thinking that right up to the point where they break the guest’s leg and baked him in the kitchen oven.

Yeah, really. They bake the guy in the oven. (The guest is a business associate who has been embezzling funds from the young Ciel, but jeez.) You do see the guest crawling away, smoking and charred and still with the busted leg, so I guess there’s a shred of plausible deniability of the fatalness of baking someone in an oven, but I don’t care. They baked the guy in a damn oven!

Naturally, I clicked the ‘Play next episode’ on Netflix.

I wasn’t too surprised when the story focused on a well-meaning but clumsy butler who worked for Ciel’s aunt. The story had some slap-stick comic relief that was similar to the burnt dinner gag.

What I didn’t expect is that the plucky comic relief clumsy butler turns out to be a villain in a later episode. So does the damn aunt!

Not just any villain, either. Ciel, Earl Phantomhive, is called the Queen’s Guard Dog, and the role of the Phantomhives through history is to take care of pesky problems for the Queen. Often employing morally dubious means to do so.

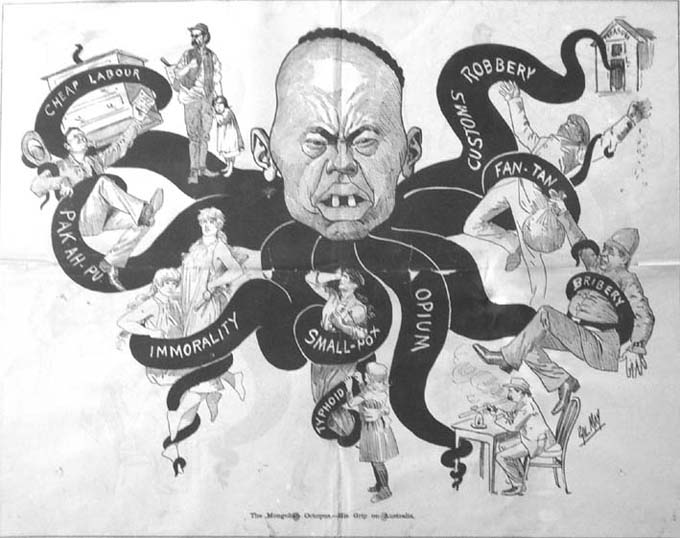

Since this is a goth Victoriana historical, the Queen’s Guard Dog is summoned to London to deal with a man who is slaughtering prostitutes in Whitechapel. I sort of expected Jack the Ripper to show up as a villain.

I didn’t expect the storyline to include the gruesome (but true) detail about Jack removing the victims’ internal organs. In Black Butler’s world, this is explicitly the women’s uteruses.

Not quite what I expected from a tween horror anime, I gotta admit.

Because cognitive dissonance is what Black Butler is all about, we get a very sweet series of scenes where Ciel crossdresses as a young fashionable lady to lure out the killer. Sebastian, the eponymous Black Butler, is disguised as Ciel’s tutor. While at a society party, the two must dance together in order to avoid Ciel’s fiance from figuring out what is going on. It’s comedic and a little silly, there’s lots of ruffles and lace, and general foolishness.

And then of course, it’s revealed that the earl they’ve suspected of being Jack is actually running some kind of underground slave / body part auction. As an old Weiss Kreuz fan, I totally saw that coming. That wasn’t too dissonant, since Sebastian uses his mad butling skillz to rescue his damsel in distress. As it were.

No, my mind went ‘wait, say again’ when the next night arrives and we discover the real identity of Jack to be Ciel’s aunt and her clumsy butler, who is armed with a magic chainsaw.

Why is Ciel’s aunt killing prostitutes in Whitechapel and stealing their uteruses? Because she lost her unborn baby and her husband in a tragic carriage accident. To save her, the doctors had to remove her uterus. She also appears to have been in love with her sister’s husband. And possibly her sister. But anyway. So the aunt is a Victorian-era gynecologist, and it turns out that performing abortions on prostitutes drives her the rest of the way around the bend. She must punish the women who got the abortions (and killed the babies she so desperately wanted) by taking their uteruses.

By why, you may be asking, is she doing this with a clumsy butler wielding a MAGIC CHAINSAW. The clumsy butler is some kind of grim Reaper, and if he saws your heart out he gets to see your life as if it was a movie. With little film-strips and everything. (Gave me flashbacks to elementary school–remember having to turn film-strips? Man, those were the days.)

Things get pretty handwavy at this point, and it’s possible my brain was going ‘whirr-click Victorian magic chainsaw whirr-click mad abortionist whirr-click whirr-click’, so I’m not all that clear on the details, but near as I could tell, the reaper-butler dude just likes killing people and watching snuff films. He’s supposedly a divine being from heaven (although why heaven is into snuff-films remains unclear.) Apparently, Sebastian, Ciel’s butler, is a butler from, yes, you guessed it, Hell. This makes them natural enemies.

(Although I was sort of confused about this, because wouldn’t a Hell demon be pro-mad abortionist and snuff film? Wouldn’t a heaven dude be anti? But I decided pondering this too much would be interrogating the text from the wrong perspective, so I settled in to enjoy the nice long butler-on-butler fight. With additional magic chainsaws. )

Sebastian kicks butt in the end, but all the butling fun and games ends when some party-pooper from Heaven shows up with some kind of weird telescoping graphite-and-steel scythe and puts an end to the festivities. Heaven-dude hauls off the reaper-butler before Sebastian can force him to reveal the killer of Ciel’s parents, servants, and the family dog.

By the time this episode is over, the viewer knows that Ciel and Sebastian have an infernal bargain. Sebastian is magically bound to Ciel–Sebastian must protect him, serve him, obey him, and, stay with him until the Very End. In exchange, Sebastian gets to eat Ciel’s soul. Ciel seems to kind of be looking forward to having his soul eaten, by the way, as if it were sort of the ultimate engagement ring in a magical marriage. I guess the original bargain was shown in that first scene where Ciel’s lying around in a sheet and surrounded by floating white chicken feathers. There’s also mystical light, a hand tattoo, an eye patch, and a Significant Trickle of Blood on a hand that has a black-nail manicure.

The whole show is a deuced odd mix of extremely over-the-top melodramaz (nothing says classy like black nail polish manicures, I always say), sort of funny slapstick, and genuinely creepy horror (baking people in ovens, mad abortionists). I really cannot recommend it on the merits of art, originality, or coherence, but I have to admit that it has a surprising amount of charm and the kind of relentless character development old soaps used to have. You keep watching because you really can’t believe they just did that.

By the way, the manga is still going strong, and my research indicates that a live-action version is currently underway.