All text from The Korean War: A History (2010) by Bruce Cumings

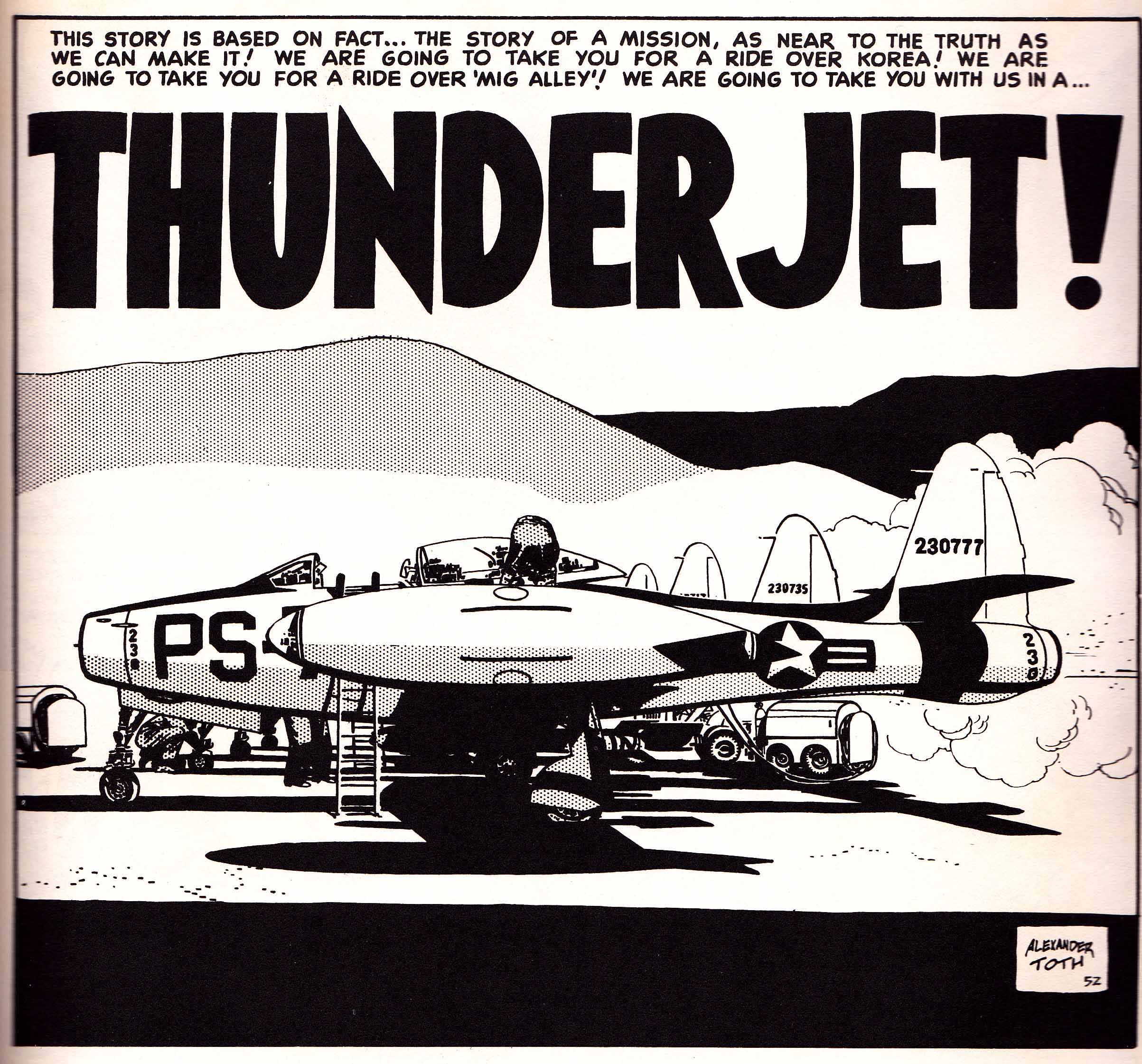

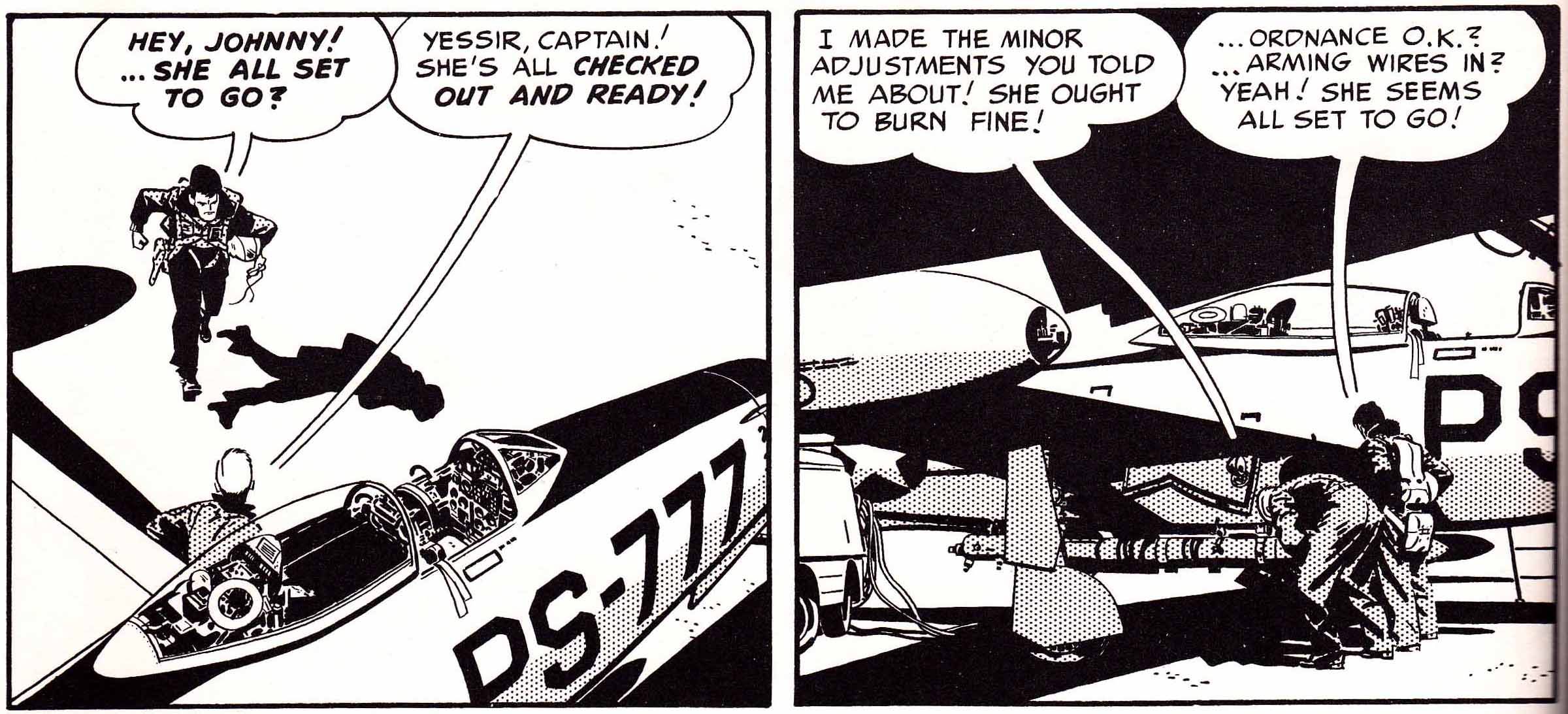

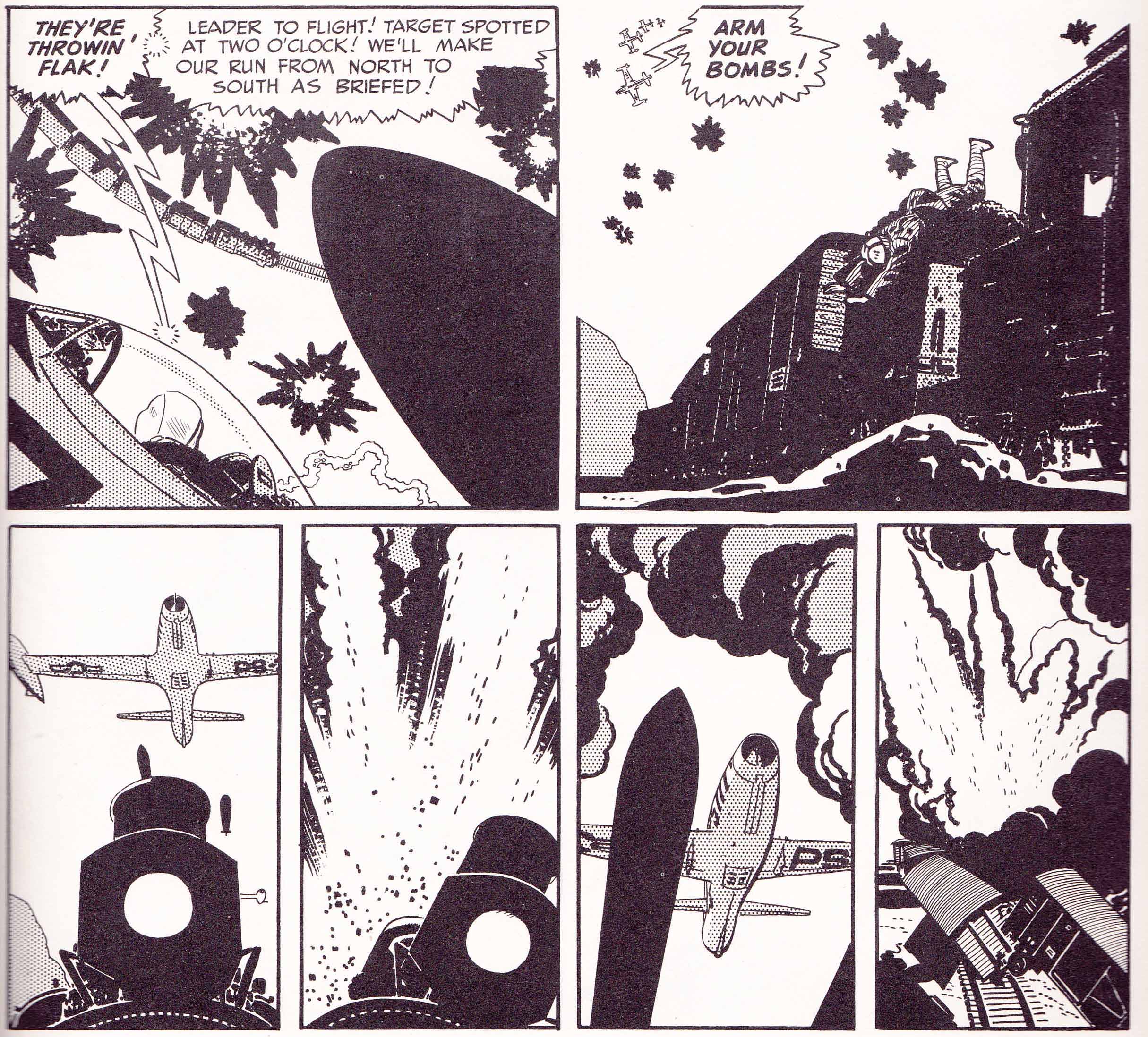

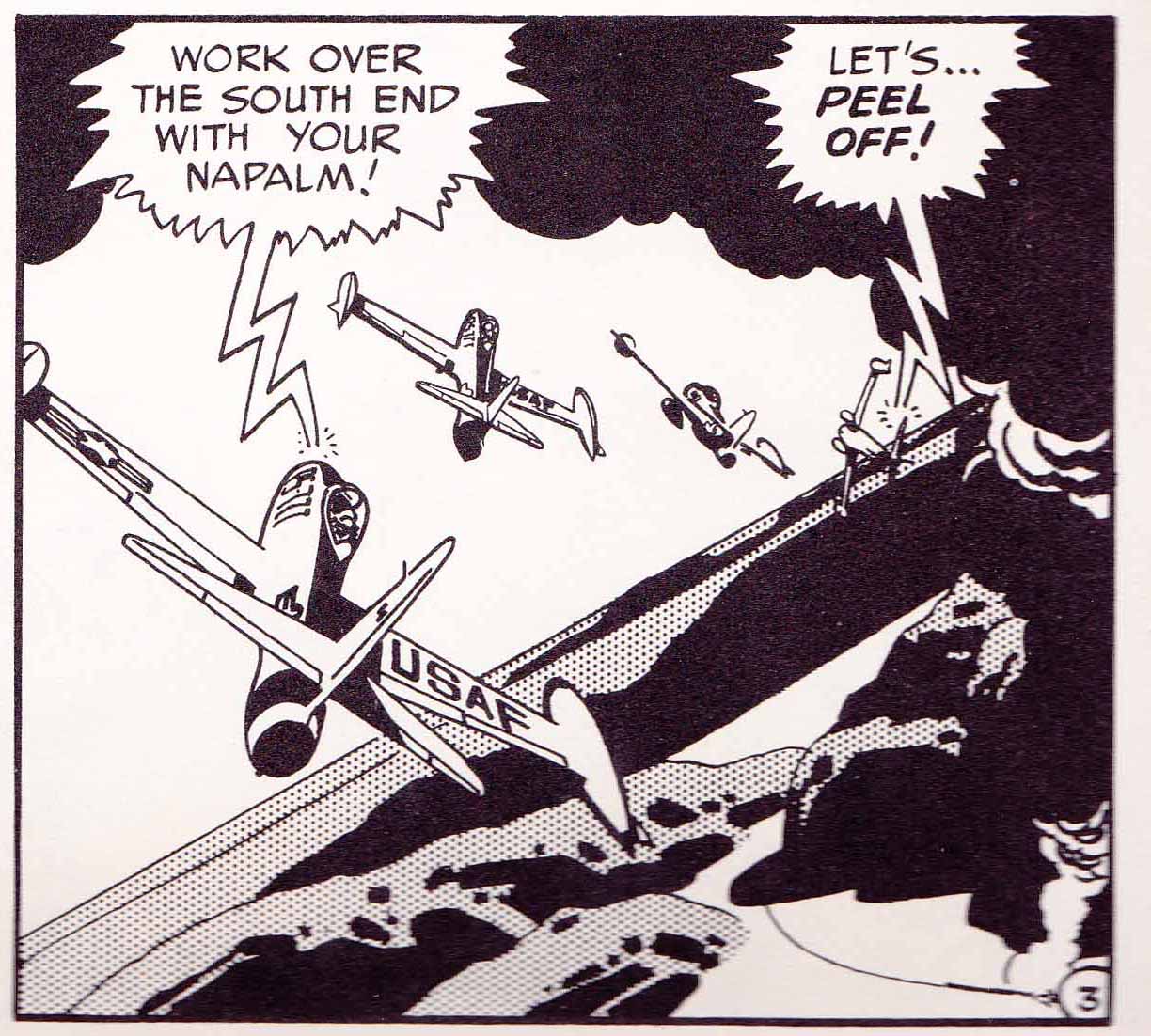

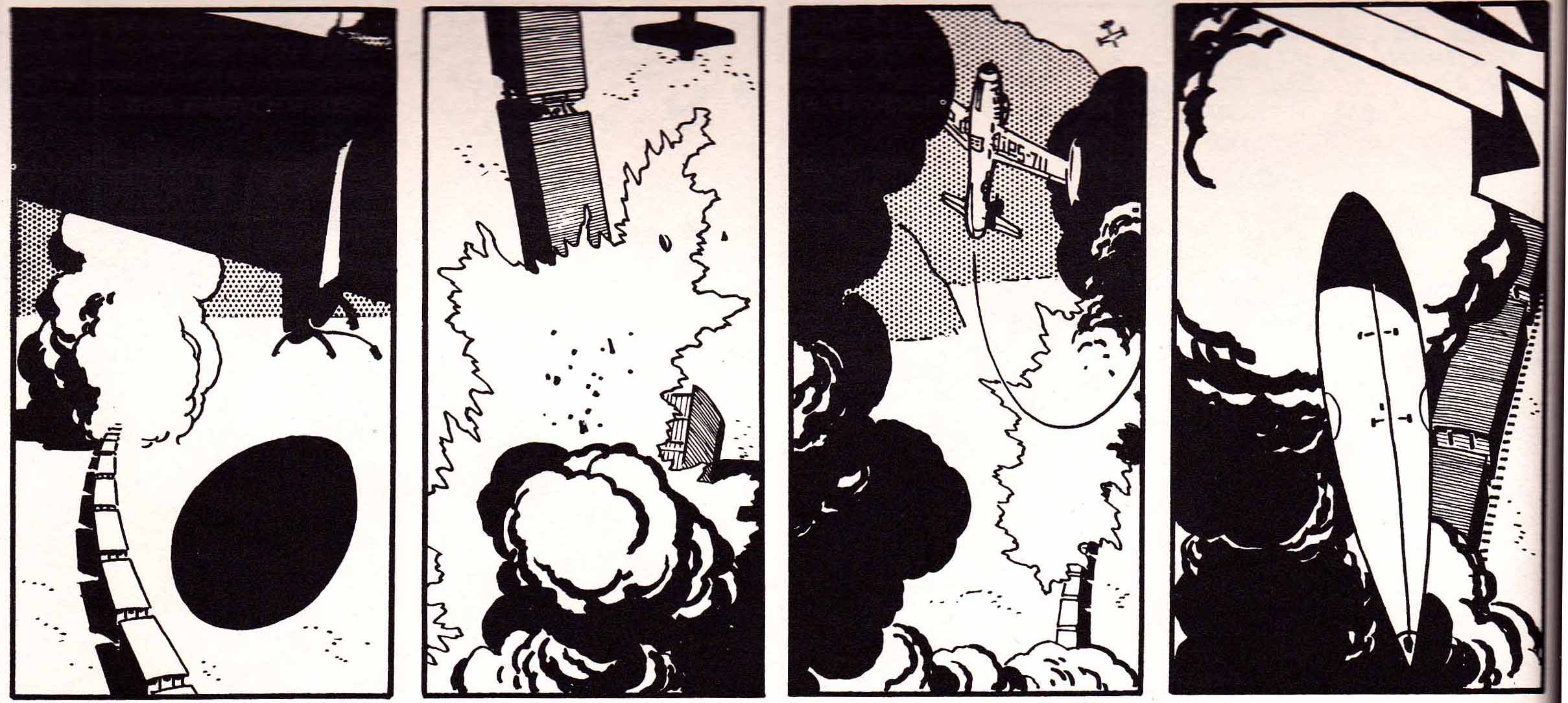

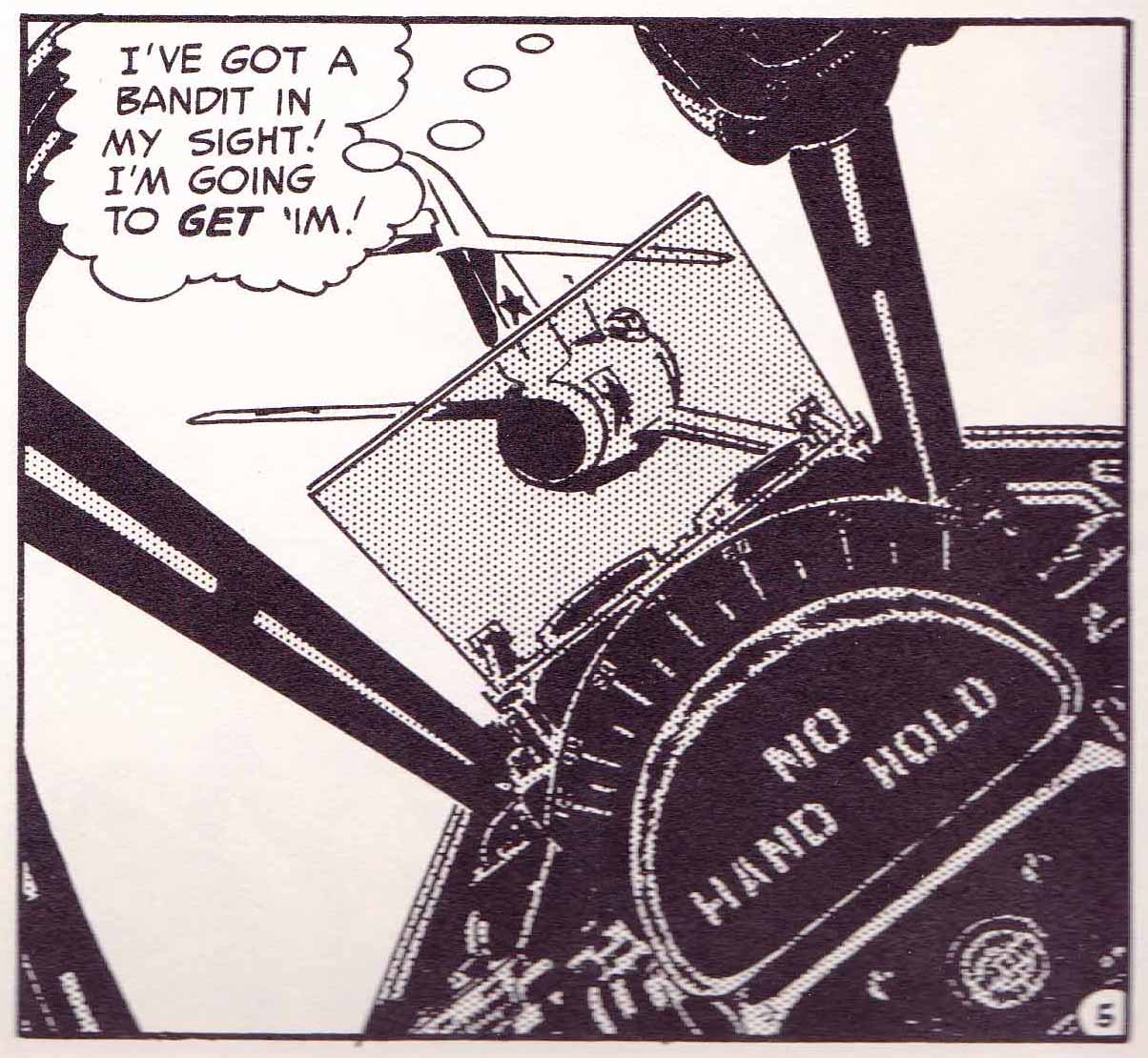

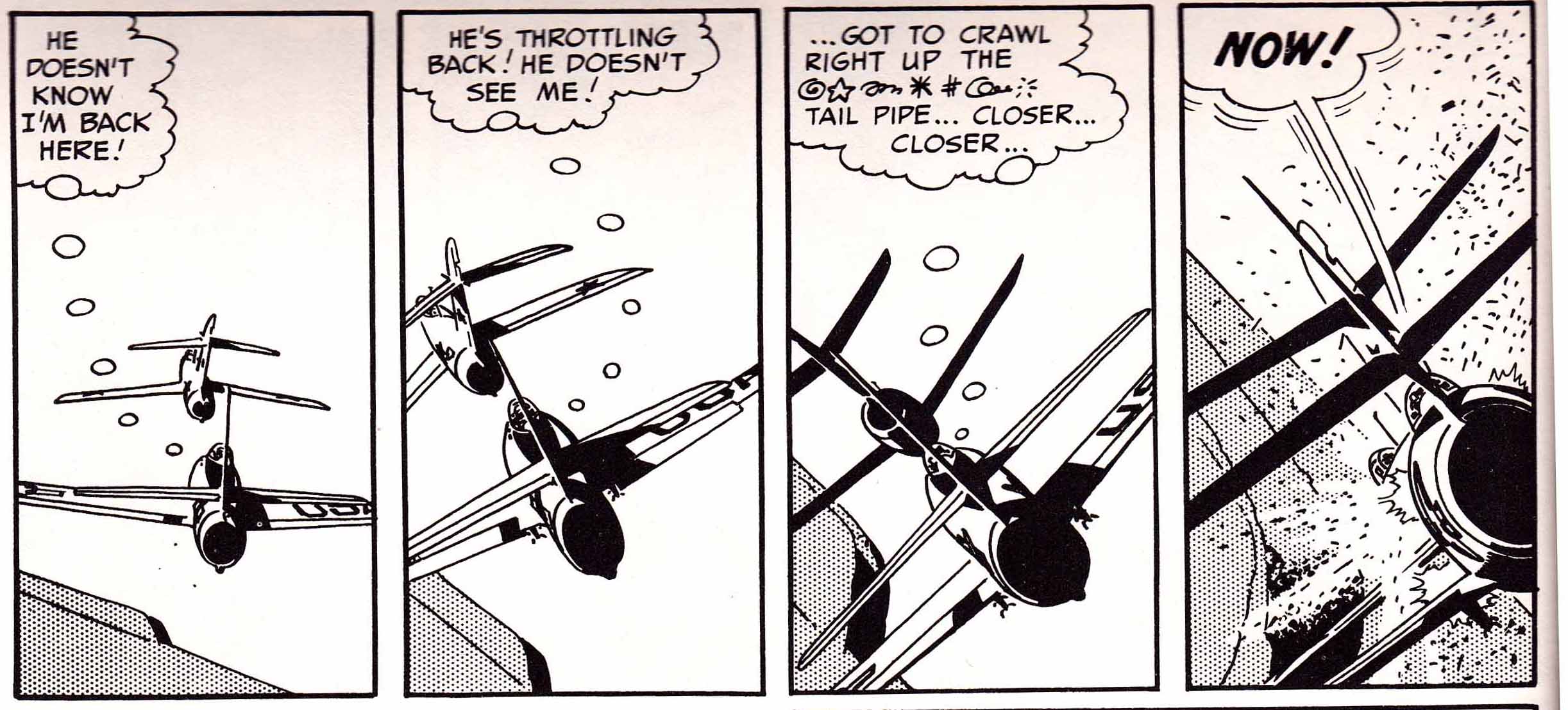

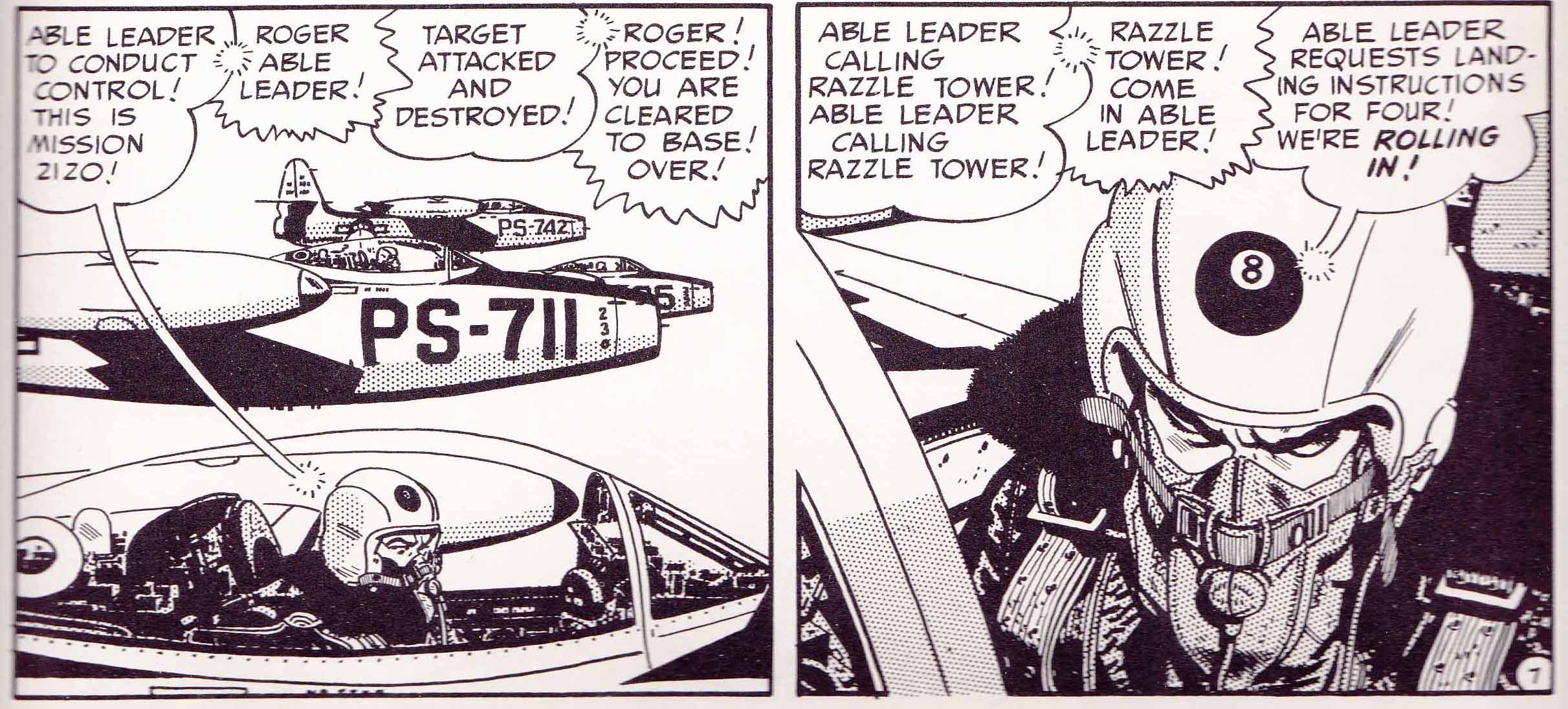

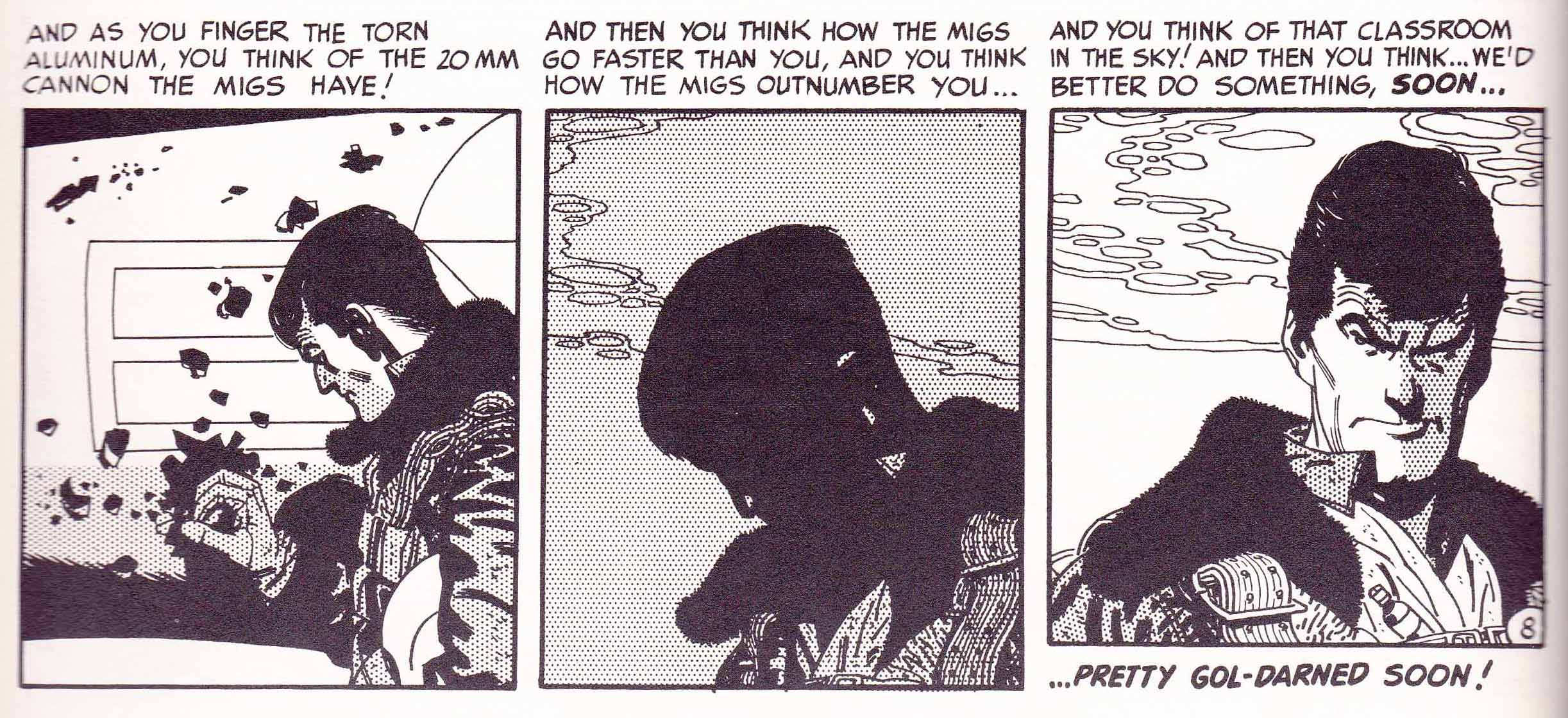

Scans taken from Frontline Combat #8 by Harvey Kurtzman and Alex Toth. A story based on fact….

______________

Curtis Le May …said that he had wanted to burn down North Korea’s big cities at the inception of the war, but the Pentagon refused—“it’s too horrible.” So over a period of three years, he went on, “We burned down every [sic] town in North Korea and South Korea too, …Now, over a period of three years this is palatable, but to kill a few people to stop this from happening—a lot of people can’t stomach it.”

General Ridgeway, who at times deplored the free-fire zones he saw, nonetheless wanted bigger and better napalm bombs…in early 1951, thus to “wipe out all life in tactical locality and save the lives of our soldiers.”

The Pujon river dam was designed to hold 670 million cubic meters of water, and had a pressure gradient of 999 meters…According to the official U.S.Air Force history, when fifty-nine F-84 Thunderjets breached the high containing wall of Toksan on May 13 1953, the onrushing flood destroyed six miles of railway, five bridges, two miles of highway, and five square miles of rice paddies…After the war, it took 200,000 man-days of labor to reconstruct the reservoir.

One day Pfc. James Ransome, Jr.’s unit suffered a “friendly” hit of this wonder weapon: his men rolled in the snow in agony and begged him to shoot them, as their skin burned to a crisp and peeled back “like fried potato chips.”

…Operation Hudson Harbor…part of a large project involving “overt exploitation in Korea by the Department of Defense and covert exploitation by the Central Intelligence Agency of the possible use of novel weapons.” This project sought to establish the capability to use atomic weapons on the battlefield…lone B-29 bombers were lifted from Okinawa…and sent over North Korea on simulated atomic bombing runs, dropping “dummy” A-bombs or heavy TNT bombs.

After his release from North Korean custody Gen. William F. Dean wrote that “the town of Huichon amazed me. The city I’d seen before-two storied buildings, a prominent main street-wasn’t there any more.” He encountered the “unoccupied shells” of town after town, and villages where rubble or or “snowy open space” were all that remained.

Meray had arrived in August 1951 and witnessed “a complete devastation between the Yalu River and the capital,” Pyongyang. There were simply “no more cities in North Korea.”…A British reporter found communities where nothing was left but “a low, wide mound of violet ashes.”

…at least 50 percent of eighteen out of the North’s twenty-two major cities were obliterated.

…the pilots came back to their ships stinking of vomit twisted from their vitals by the shock of what they had to do.

For real

I’m not especially knowledgeable on the Korean War, so while I assumed it was horrible (like all wars) I didn’t necessarily know the details.

North Korea’s economic woes are often linked to its pathological government, which I’m sure is true to some extent. The fact that (as this suggests) the entire country was devastated by the U.S. can’t have helped matters either, though.

There’s the pathological and incompetent government, and there are also the huge economic sanctions in play (which was probably a factor in triggering the recent nuclear stand-off).

It’s certainly a forgotten war though this is one instance where people who read comics (the EC ones in particular) could become familiar with names like Imjin, Changjin, and Yalu etc.

The Cumings book is short, informative, and very easy to read. I think he’s sometimes accused of being too liberal but that’s hardly a damning criticism in my book. The strongest parts of the book are those in which he explains why this (civil) war started and hasn’t really ended. Most see it as a war of ideologies but it was also a war between Japanese resistance fighters (one could see them as “patriots”) and Japanese collaborators (the South).

Not to mention the fact that it has had ramifications for American foreign policy ever since – the real beginning of the military industrial complex, and the tussle between containment and “rollback” (hence the humanitarian disasters in Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya etc).

Wait, war is bad, and comics didn’t get it right? STOP THE PRESSES!

It’s not that all comics didn’t get it right. It’s that this one didn’t…and that looking at the way it failed to get it right makes it look banal and ugly and kind of evil.

This kind of makes Toth look like Leni Riefenstahl – an outstanding artist, dedicating his skills to the worst kind of propaganda. I find it hard not to swoon over these flawless drawings … and some people would argue it’s simply an indication of bad taste, but I’m not sure it’s that easy. Anyway, it’s always good to be reminded how we’re constantly being manipulated, even in western democracies.

In defense of Toth and Kurtzman, it’s possible that they had no *easy* way of knowing since most American papers and magazines were “censored” within the first few months of the war (I think; the comic was released in 1952). They would have had to do a bit of research to get to the truth. So they were duped along with the rest of America. I doubt if most Americans nowadays know that Korea was carpet bombed during the war. I suppose comics historians would give Toth and Kurtzman some credit for thinking about the Korean war at all.

So the comparison to Riefenstahl is a bit too extreme in my view.

Speaking of manipulation: “…at least 50 percent of eighteen out of the North’s twenty-two major cities were obliterated.”

What, 9 out of 22 or 41% doesn’t sound sufficiently awful?

But this is a great idea. Contrasting old innocent/ignorant narratives with a much darker reality is regularly done in documentaries — Michael Moore for one — but not that I can remember with comics.

Whoops; sorry. I didn’t read closely enough. I’m ignorant, not malevolent!

41% does sound awful enough, though. You’re right.

Also…it’s interesting that you seem to be implicitly saying that what Suat has done here is a comic itself, rather than (or in addition to being) criticism. I hadn’t thought of it that way, but I think it works; he’s juxtaposing images and text to create a new/competing narrative.

True, Nazi comparisons are too extreme most of the time and probably a bad idea in general, for obvious reasons. I only brought Riefenstahl up because there’s no denying the artistic merit of her propaganda films and how her aesthetics still influence today’s advertising and film making.

I didn’t read your ignorant malevolence, so no problem.

I suppose the closest examples to what Suat’s done are the sites recontextualizing old Batman and Superman comics, but they depend on the reader to supply the sexualized reading. I’d buy that he’s made a new comic through sampling.

Actually what Cumings meant was that in 18 out of 22 of North Korea’s cities, over 50% of the infrastructure/buildings/etc. was destroyed. I just discovered that the entire chapter is online and he has a partial table on the individual cities and figures. Apparently more bomb tonnage dropped by the US in Korea than the “entire Pacific theater in World War II.”

Pyongyang, 75%

Chongjin, 65%

Hamhung, 80%

Hungnam, 85%

Sariwon, 95%

Sinanju, 100%

Wonsan, 80%

Oh. That’s much more awful.

“Apparently more bomb tonnage dropped by the US in Korea than the “entire Pacific theater in World War II.”

Holy crap.

I presume that “less than 50%” doesn’t mean zero…so is it right that a significant percentage of every single North Korean city was destroyed?

And 100% of the infrastructure and buildings of Sinanju were destroyed. Is that worse than Hiroshima?

And yet people wonder why the North Koreans still hate us….

Also, something horribly ironic (not from Cumings book): the city mentioned above which was totally obliterated (Sinanju) literally means New Safe Province according to the Chinese characters which make up its name.

You see that [sic] in the first quote in the article. That’s Cumings correcting Le May. Because Le May didn’t actually destroy *every* Korean city even though he said he did.

I don’t have the book on me at the moment so I can’t check the reference Cumings provides on the city damage.

The North Koreans also haven’t completely forgotten the massacres as well, meaning acts of mass murder. 30,000 killed by N. Korea and about 100,000 by the South. Lots of blame/evil to go around.

Kurtzman at least began his tenure on his war magazines with an antiwar tone. But, as noted by John Benson, as Kurtzman researched his books and became more chummy with his sources, his stories moved more to a militaristic viewpoint, like that of today’s embedded press. You’d be hard pressed to come up with someone who admires Toth’s artistry more, but I must ignore his beliefs because politically, the man was far to the right. After his non-combatant tour of duty as a graphic artist on his post newspaper in Japan, he asserted that he “enjoyed” his service. One of his specialties was his glamorized renditions of aerial combat. A rabid anti-communist, it is alleged that he and John Severin “joked” in a bullpen setting about bashing Chinese babies against a wall after their birth. Another war story drawn around the time of his E.C. work was done for Standard and featured a gleeful depiction of Army engineers burying Korean soldiers alive using steamshovels.

Ah, listen to all of the bleating from liberals who’ve spent their lives listening to selective arguments about what “really” happened in Korea.

As always, when liberals discuss most historical versions or depictions U.S. involvement, words like propaganda, manipulation, U.S. war crimes, and other such condemnations are tossed around like confetti.

Are they true? Yes and no.

Was there propaganda and manipulation in popular culture regarding U.S. actions during that war? Sure! But that’s not exactly a news flash — especially when there are strong feelings about the ultimate reasons we were involved in Korea in the first place. Truman and others certainly believed we were doing the right thing by being there.

So what about the charges of war crimes? Well, in any war, it can be argued that either side was guilty of them. The fact is, it is absolutely impossible to prevent war crimes in any war. There are too many individual personalities in armies on either side to prevent them. But if the general policy of one side is to try and prevent civilian casualties and prevent war crimes whenever possible, and the other side simply does not care, then I would say one side has the greater moral high ground than the other. The only way war crimes can be totally prevented is to not have a war in the first place. Unfortunately, since I do not see war going away any time soon, we’ll have to just continue to judge the belligerents by their general efforts to prevent civilian casualties whenever possible.

I think it’s safe to say that during the Korea War, the U.S. had greater concern towards the ultimate loss of life than their opponents, and the U.S. also had an eye on the clock — always hoping to end the conflict in the quickest way possible to avoid prolonged losses and civilian bloodshed.

The North Koreans and Chinese did not care how long the Korean War went on. There is ample evidence they planned on fighting as long as it took to either win, or get conditional terms of surrender that were advantageous to them their regimes.

My problem with the liberal narrative for the Korean War is that it almost NEVER discusses what the “bad guys” did or what they were planning to do.

I’m very familiar with the Korean War, and I was stationed in the Republic of Korea (South Korea) for a year in 1998.

Like almost every liberal who seeks to re-write history, Ng totally ignored in his essay what the North Koreans or Chinese did during the Korean War.

First of all, in a surprise attack, North Korea invaded South Korea. This attack brutally swept through the entire peninsula in a month, and pinned the badly outnumbered U.S., South Korean and other coalition forces on southernmost tip of South Korea behind the city of Pusan and the Naktong River. Along with the hasty reinforcements flown and shipped into Pusan, the only other thing that prevented the fall of South Korea was the air superiority campaign Ng criticizes.

In short, South Korea as we know it today was within an eyelash of being part of the North Korea we know today.

The North Koreans destroyed everything in their path, and the U.S. responded in kind. Unlike the coalition forces, however, the North Koreans executed anyone associated with the South Korean government in any way, plus anyone else they felt like killing, be it educators, business owners, intellectuals, etcetera.

The U.S. and coalition forces began to counterattack about two months into the war, and started to take back South Korea inch by inch. McArthur’s brilliant amphibious landing at Inchon cut off the North Korean army in the south, and the North’s campaign began to crumble. Less than three months after the invasion began, U.S. and coalition forces re-take the South Korean capital of Seoul, and press into North Korea. Less than a month later, the North Korean capital of Pyongyang was in coalition hands.

Then, contrary to the U.S. intelligence consensus that the Chinese would not cross the North Korean border and intervene, the Chinese crossed the North Korean border and intervened (is the CIA ever right?). Chinese forces, using brutal total war tactics, then began pushing back coalition forces from the North. Successful, they push past the 38th Parallel and re-take Seoul.

The U.S. and coalition forces then dig in and counterattack. They re-re-take Seoul in the spring of 1951. Battles rage back and forth while peace negotiations commence. Eventually, there’s a stalemate as coalition forces cease attacks and dig in. The North Korean commanders then begin their characteristic phony negotiations, to which the South begins an air campaign against the North. Eventually, the North gets tired of getting bombed, so they agree to a cease-fire.

That was 60 years ago.

We are technically still in a state of war with the North, and while most Americans are oblivious to it, there have been many, many instances in the interim where the North has attempted to re-start a war with the South. For example, one alone could easily write a book about the North’s relentless campaign digging invasion tunnels into the South.

I can attest from my tour in South Korea 15 years ago that U.S. and ROK forces are still on hair trigger alert all these years later.

Not that any of this would be apparent by Ng’s essay. His propaganda, in my mind, is no different than the propaganda he criticizes. As the age-old saying goes: “Two wrongs don’t make a right.”

Hey Russ. Just fyi, Suat’s given name is Suat (though maybe you were using the family name intentionally?)

“I think it’s safe to say that during the Korea War, the U.S. had greater concern towards the ultimate loss of life than their opponents, ”

It’s just really difficult to know what this means, or why it means anything that matters, when you’re looking at flattening the bulk of 18 cities, and probably a significant percentage of the rest, or when you’re talking about using napalm. Those are pretty awful things to do by any moral standard that makes any sense. The fact that someone else over there may be doing something worse (or I guess might do something worse if they had the wherewithal) is neither here nor there.

What I think you’re maybe missing is that Suat’s piece isn’t pro-North Korean. It’s contrasting a view of the war as heroic and honorable and exciting and manly with fairly strong evidence that the war was a horrible, inhuman slaughter.

You can certainly argue that the horrible, inhuman slaughter was justified because the other options were worse. But that’s not what the comic is doing. It’s presenting the war as noble and heroic and cool. Wholesale slaughter of civilians is not noble and heroic and cool, no matter what the North Koreans did, or no matter how horrible they were.

I think your correct, incidentally,that war crimes are part of war. That’s a reason not to go to war just about ever, though, not an excuse for war crimes.

And yes the North Korean regime is horrible. Why that should excuse bombing infants, I don’t really know.

Ah, listen to the predictable barking from the conservative fluff writer for the military, blah blah, etc.

Russ: There are quite a few factual mistakes in your comment but anybody looking for alternative views can easily find them online. So I won’t bother. I will say that these two parts do standout in the way they conform to the propaganda of the day.

(1) I think it’s safe to say that during the Korea War, the U.S. had greater concern towards the ultimate loss of life than their opponents

(2) Unlike the coalition forces, however, the North Koreans executed anyone associated with the South Korean government in any way, plus anyone else they felt like killing, be it educators, business owners, intellectuals, etcetera.

The latter is so grossly mistaken as to the balance of evil (as I’ve said above, lots to go round) you have to shake your head. Even the South Korean Truth and Reconciliation commission (yes, Wiki it) recognizes as much. The evil of the present day North Korean regime doesn’t alter these facts. Worse, it denigrates the sterling work of the South Koreans in facing up to the crimes their leaders did in their name.

Many self-proclaimed liberals hold to these views in America’s current wars it has to be said. So it’s not a conservative thing.

Here’s just one paragraph from that truth and reconciliation article.

“The commission concluded on March 11, 2008 that indiscriminate bombing by the US on[9][10] Wolmido Island, Incheon, Korea on Sept. 10, 1950 caused severe casualties of civilians residing in the area. At the time, the United Nations attempted a sudden landing maneuver in Incheon to reverse the course of the war, and Wolmido Island was a strategically significant location that needed to be secured. [11] It is assumed the US decided to clear any potential threats therein to minimize casualties among its own troops, and thus conducted indiscriminate bombing of the region, resulting in massive civilian casualties among the local villagers. Surviving villagers were forced to evacuate their homes and have not been returned, since it became designated as a strategically important military base even after the Korean War. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has recommended that the Korean government negotiate with the US government to seek compensation for those victimized by the incident. [12][13]”

James, if you’re still around, where did you get that anecdote about Toth and Severin joking about bashing Chinese babies. Is the Standard comic online – I’ve never read it. What is it called?

Gil Kane reported that Toth made the same remark to him.

Yes, Alex, I got that disgusting anecdote from a Gil Kane interview. Suat, the Standard comic is in the recent, excellent Fantagraphics Standard collection. The E.C. stories are better by far, but Toth’s two aerial stories came from Kurtzman’s imbedded phase.

In any wartime situation, good intel is usually the first casualty. That’s why Pearl Harbor happened. That’s why the Battle of the Bulge happened. The list is endless.

Just prior to the Korean War, we were pulling out our troops en mass while the North was prepping for war. Why? We were clueless there was a threat of invasion. Truman was assured the Chinese would not cross the border into North Korea and intervene. They did, and a bloody war dragged on for another two years.

Yet, you expect the US and ROK generals preparing for a surprise attack at Inchon to know who was occupying a strategic island along the invasion route? And what were they supposed to do in a fast-moving campaign to take back South Korea? Keep in mind that just a few weeks earlier, those same generals had their backs to the sea at the southernmost tip of the Korean peninsula.

So, yes, the civilian casualties were terrible, but who started the war in the first place? And who started the scorched earth campaign that nearly wiped out a sovereign country?

Why are they demanding reparations and/or accountability? Because they’re dealing with the US and South Korean governments. You can bet if the North Koreans had won the war, you wouldn’t hear a peep from anyone, because, after all, we are talking about one of the most repressive and brutal regimes in modern history.

Maybe you would have preferred Truman to do nothing? That’s the only way things like the Inchon-related shelling, et al could have been avoided.

Ditto for World War II. Should we have simply appeased the Japanese and given them access to the strategic materials their war machine was seeking? Or should we have told Churchill “tough shit” when he came to a then-neutral US begging Roosevelt for war materials?

If we had, think of all the lives we’d have saved on BOTH sides, right?

It’s easy being a critic, and an armchair general. So instead of empathizing solely with the helpless victims, try and also empathize with the people who are stuck making all of the shitty decisions.

If you were MacArthur, Ridgeway, LeMay, Truman or whoever, what would YOU have done? And would your decisions have prevented a war shortened the war, prolonged it, lost it, won it, or have it end up a 60-year stalemate? At what cost?

Russ, your argument boils down to, “North Korea is evil, evil, evil,” and “We’re better than North Korea.” The second argument is incompatible with the first. If the enemy is absolutely evil, stating that you’re better than them is a bare minimum for moral action, you’d think, not an actual effective argument that the US is good, or even anything other than evil, evil, rather than evil, evil, evil.

Decisions about war and peace are hard. Again, it seems like you can’t claim that they are hard and simultaneously sideline the most important issues. If atrocities are just one of those things, and you can’t really expect to think about them, then why bother worrying about whether a war is just or not?

Dresden and Hiroshima show pretty clearly that acts of unspeakable atrocity can be committed in even the best cause. From your perspective, that seems like a reason to sneer at anyone who criticizes the atrocity. I don’t find that a compelling or serious argument.

Fighting the Korean War was either worth it or it wasn’t.

Lawyers and anti-war activists stoke reparations, tugging at heartstrings of survivors, politicians and others — pretending that events like this can always be avoided by good leadership.

But anyone familiar with war knows that the only “always” is there will always be civilian casualties — even under the best of circumstances, and even by the very best and most competent generals.

The lawyers involved in any type of reparations are usually ambulance chasers looking for money, and the non-lawyer reparation catalysts are usually anti-military activists who spend their lives “exposing” wartime sins.

Inchon was critical to saving a democratic South Korea. If Inchon had failed, or not taken place at all, the entire peninsula may have fallen.

So the question isn’t should the folks on Wolmido Island be getting compensation, the question should be, “Was the Korean War worth fighting in the first place?”

If the answer is “yes,” then the shelling was justified and simply one of countless other tragedies that took place while the US, ROK and coalition partners fought, and died, tried to repel South Korean invaders.

If the answer is “no,” then I don’t know what to tell you. All I know is I sure as hell wouldn’t want to be living in North Korea.

The end of the second-to-last paragraph should read: “…tried to repel South Korea’s invaders.”

But you probably already knew that.

“Fighting the Korean War was either worth it or it wasn’t. ”

Hey Russ. We’re talking about butchered civilians, murdered infants, cities leveled, and people with their skin burnt off. Reducing that to “worth it or not” is, frankly, evil and stupid.

It’s a nice illustration of how a simplistic utilitarian moralizing can be used to justify anything and everything, up to genocide, without having to think about it too hard, though. So thanks for that.

Oh…and the US didn’t save a democratic South Korea. South Korea wasn’t a democracy after the war. It was an authoritarian state. They moved to democracy later, but to say we were fighting for democracy is a serious misrepresentation.

“All I know is I sure as hell wouldn’t want to be living in North Korea.”

Oh, and I wouldn’t have wanted to be living in North Korea while we were leveling the place, even more than I wouldn’t want to live there now. The continued economic and political mess there now might also have something to do with our having inflicted a holocaust on them within recent memory. It can take a long time to recover from something like that.

Don’t get me wrong; the North Korean regime is horrible. But the fact that someone else somewhere is horrible is not license to do anything we want anywhere in the world and feel good about it. Suggesting that it is isn’t hard nosed realism. It’s blind self-regard and willful ignorance.

“It’s a nice illustration of how a simplistic utilitarian moralizing can be used to justify anything and everything, up to genocide, without having to think about it too hard, though. So thanks for that.”

Russ is more of a deontologist, I think. What matters to him isn’t so much the number of lives, but being on the right side of the affair.

Well, he said “is it worth it.” That seems to be cataloguing lives or pain or happiness or something in a utilitarian manner.

“Russ is more of a deontologist, I think.”

I agree. Deontology is what makes Russ’s invocation of evil as the ultimate trump card make sense. Fighting evil is always “worth it,” no matter the cost. Any utilitarian concerns and calculations about the pains and sufferings inflicted on the people involved miss the point — or, rather, are beside the point.

Hmm. Maybe I need to revise, given the fact that Russ never actually uses the word evil: that comes from Noah’s version of Russ’s argument. But he does seem to insist that you have to make more moral calculus first — what kind of enemy is this, and must this enemy be stopped? — and then follow through with whatever tactics will allow you to meet that goal. It is more than proportionality; it is total commitment to the defeat of the enemy, once you decide that they need defeating.

That seems right to me, Peter. From the SEP’s entry on deontological ethics, there’s this criticism of consequentialism: “And there also seems to be no space for the consequentialist in which to show partiality to one’s own projects or to one’s family, friends, and countrymen, leading some critics of consequentialism to deem it a profoundly alienating and perhaps self-effacing moral theory (Williams 1973).” Russ seems pretty opposed to any view that wouldn’t account for patriotic allegiance.

Doesn’t the insistence on patriotic allegiance rather undercut the insistence on fighting evil, though? That is, there seems like there’s a fair amount of blurring between “we are good, therefore patriotism,” and “patriotism, therefore we are good.” I don’t see a whole lot of space to condemn America ever for anything. If we’re good, then military power is always justified…and conversely, the righteous use of military power ensures our goodness.

Back to the original post, I like Suat’s repurposing of “Thunderjet!” It seems to function like a smaller version of what Jochen Gerner is pursuing with Panorama du feu, or — stretching it a bit — the found footage assemblages like Bruce Conner’s “Report” or Arthur Lipsett “21-87.” It re-releases the violence trapped in the drawings, beneath the controlled linework.

At the same time, my first reaction was that Suat’s “exposure” of Kurtzman and Toth’s complicity seemed sort of cheap, like the kind of thing that could be created by juxtaposing any WWII comic with, say, passages from Paul Fussell’s Wartime. I no long feel that way; I do admire what this post accomplishes. Perhaps all war comics and films need similar treatment.

But I still wonder if it keeps one from trying to get a handle on what Kurtzman himself was trying to do — or thought he was trying to do. It lines up these heroic and, indeed, glorious looking images with horrific text, presenting Kurtzman as engaged in sheer jingoism. But even this most “embedded” (James’s term) of Kurtzman’s war stories seems marginally uninterested in gilding its actions in glory (it’s a job, with little celebration), and surprisingly uninterested in demonizing the enemy pilots (“Those jets are being flown by kids…no formation, no nothing! They come up, every day, like a class room”).

Of course, it remains a propaganda piece: our guys (outgunned, outnumbered) need bigger and better planes! But Kurtzman didn’t think of it as necessarily noble or patriotic, and indeed blamed Toth for (somehow) inserting the “patriotism” into the story. “I wish,” he once said, “this guy wasn’t made to look so goddamned noble in the last panel”.

How can Kurtzman not see what his own story is engaged in? How does this work sort of gag on the patriotism and that is central to its entire tale — and that, as a mouthpiece for the Air Force, it must swallow whole? There are interesting things one might ask about the story. But Suat’s approach, in pursuing other objectives, cannot ask or recognize them.

” But Suat’s approach, in pursuing other objectives, cannot ask or recognize them.”

Can’t do everything all at once! If you wanted to write a piece with a different focus, though, I’d publish it in a second.

“Can’t do everything all at once!”

I absolutely agree with this. But I wanted to note that to take approach “A,” you need to flatten out the story, ignoring the very things that would allow you to raise question “B.”

Noah wrote: “Hey Russ. We’re talking about butchered civilians, murdered infants, cities leveled, and people with their skin burnt off. Reducing that to “worth it or not” is, frankly, evil and stupid.”

No, it isn’t.

Every single war needs to be distilled down to one simple question: “Is it worth it?”

It’s governments (and sometimes the people) that decide the scope of “worth it,” and any country that opts to go to war better be damn sure they understand the consequences.

I certainly do, but you apparently don’t. You appear to think that war can be “more sterile” and/or “less horrible” — and that reparations will somehow make it so.

News flash: It can’t.

Ever.

Regardless of how careful and how sensitive a commander is, innocents will die. There will also be friendly fire casualties. It will happen.

The only saving grace is that in the past 20 years, conventional warfare has become more precise, reducing the incidents of collateral damage compared to WW II, Korea and Vietnam. Unfortunately, knowing our anti-war crowd the way they do, many of today’s combatants don’t wear uniforms, and they shield themselves with family members wherever they go.

But this tactic isn’t new. During World War II, the Japanese decentralized much of their war manufacturing throughout residential areas, hoping it would prevent its destruction. But today, blending in with the local populace — hiding in plain sight — is becoming more and more commonplace.

So war will always be bloody. Men will die, women will die, children will die, and babies will die. There simply are no exceptions. Which means if a country commits to a war, they’d better be damn sure the inevitable price is worth it.

So, I repeat. Was it worth stopping North Korea and the Chinese during the Korean War? Was it worth stopping the Nazis and Imperial Japan during World War II? If the answer is yes, regardless of how much you hem and haw and qualify your answer, then you ought not be playing armchair general 60 or 70 years after the fact.

Hey Russ. Nope, it’s still evil and stupid. When you make your morality dependent on a single question like that, you bracket basically everything that matters. Your discussion there isn’t a way to make clear decisions; it’s a way to give yourself carte blanche to do enormously evil things as long as you’ve decided your enemy is evil enough.

It’s kind of taking Niebuhr’s pragmatism to absurdity. Anything is sanctioned as long as you can claim to have done some sort of pragmatic calculus. Again, it’s a fine distillation of how our national ethical structure actually seem to function in these situations — that is, not at all.

Ugh, that someone with so much contempt for “liberals” who dismisses the “anti-war crowd”, someone whose vaunted military experience hasn’t been in combat, is in essence not only an armchair general himself but worse: as a active publicist and “entertainment liason” for the military, the worst sort of glamorizer of war

Oh…and Russ, I agree that war is always horrible, and that you need to know the price. But mocking people who point out the price isn’t evaluating the price carefully. It’s refusing to think about the price.

Reparations are a way to think about the fact that you got the price wrong. It’s a way to fess up to the truth that people do things in war that are wrong, and often that didn’t need to be done, because you’re scared, or stupid, or just because when you’ve got a gun and an enemy you stop thinking of the latter as human.

Reparations are a way to say that we’re not defined by, nor eager to embrace, the worst things we’ve done in the name of defensive self-justification and hubris. War crimes will always happen as long as there’s war. But that doesn’t mean you have to embrace them, or boast about them as a sign that you really understand war while others don’t. We’ll have the poor with us always too, but the corollary to that is not that you should kick poor people when you see them in the street.

Of course, just because Russ was contemptuous of us so-called liberal anti-war crowders doesn’t mean I should be so much of a prick and so, I apologise for my rudeness in criticizing HIS general credentials.

Since this thread began by juxtaposing Bruce Cumings’ words with an EC comic book story, I’d like to quote what Cumings wrote in _Origins of the Korean War_ about the effects of the images of enemy cruelty that appeared in Korean War comic books on his own thinking:

“Growing up on comic books depicting North Korean and Chinese soldiers as rabid, bloody-fanged beasts, for years I could not purge from my mind the notion that fighting such people must have made the Korean War a horror. Yet all testimony points to the very same ‘Red Chinese’ as the most disciplined and correct army in the war. That could be verified a thousand times, however, before it would erode the residual Orientalism infecting the Western mind, from the simplicity of comics to the august judgments of contemporary advocates of ‘the West.’”

Cumings quickly adds that “The numbers game [of comparing atrocities] is nauseating,” and that all sides in the Korean War “were guilty of unforgiveable atrocities (although none held a candle to the Germans or Japanese in the just-concluded world war.)”

R. Maheras, if you have time and interest to continue this discussion off-list, I’d be glad to hear from you at rifas@earthlink.net. (Much, but not all, of what I would like to discuss would be off-topic for a comics site.)

Leonard: I think you can safely assume that almost nothing is off-top for this site or this thread. So discuss away.

Thanks for the invitation! I am trying to complete a book about Korean War comic books, so I found this conversation and the piece that sparked it very interesting. Several have commented that it’s hardly news that comic books do not show how bad war is, but I find that looking at particular examples of war comics in detail helps demonstrate the possibilities and the limits of comics in a new way and also can raise understanding of forgotten Cold War history.

In reply to some of your own comments, I would say (1)Kurtzman did an _extraordinary_ amount of research, and did not simply rely on censored material that appeared in newspapers and magazines (2) You wrote that Cumings said “sic” about Lemay’s comment about destroying every Korean city to correct him. Lemay had said every Korean “town.” Until now, I had thought Cumings’ “sic” was for emphasis (3) You wrote that Toth and Kurtzman deserve credit for “thinking about the Korean War at all.” By my count, Frank Motler’s checklist of the Korean War comic books that were published from 1950 to 1955 includes 919 issues of 113 comic book series from 32 publishers. Kurtzman deserves credit as one of the first comic book editors to respond to that war, and as the first to try to present a _realistic_ view of what was happening there in comic book format. This ambition to be “realistic,” and not only the great skill of the writing and art in _Two-Fisted Tales_ and _Frontline Combat_, make the project of comparing his comics with the events that inspired them illuminating.

Suat – I was not “grossly mistaken” about the balance of evil, as it is estimated that the North Koreans executed 500,000 intellectuals and government members (and their families) during their initial invasion of the south, AND during their retreat. Nor did I make “numerous” factual errors about what happened about the Korean War.

While we’re on the subject of gross mistakes, you, on the other hand, wrote an essay about Korean War crimes and mention only the United States, totally ignoring war crimes by everyone else.

You also make no mention of the enormous evacuation efforts the UN coalition made to get civilians out of the rapidly-changing war zones in BOTH North and South Korea to the relative safety of Pusan, where the South Korean government re-located to when it initially fled Seoul. Hundreds of thousands were evacuated by Navy ships, and the rest went via land routes.

Far worse than that, however, you portray North Korea as a victim in a war THEY started, and one THEY could have ended a year later, if they had only agreed to the U.N.’s cease-fire negotiations. Instead, they suspended talks, and the war went on for another two years. Why the refusal? Aside from being belligerent pricks, they thought that, despite their setbacks, they had the strategic upper hand. Most of the bombing you condemn occurred AFTER the North Korean’s initial cease-fire refusal, so it’s their own fault they got the shit bombed out of their country.

Noah wrote: “Hey Russ. Nope, it’s still evil and stupid. When you make your morality dependent on a single question like that, you bracket basically everything that matters. Your discussion there isn’t a way to make clear decisions; it’s a way to give yourself carte blanche to do enormously evil things as long as you’ve decided your enemy is evil enough.”

Wrong. Any leader contemplating going to war has to answer that number one question first: Will it be worth it. Will it be worth the blood of your military, the blood of the innocents caught up in the fighting, the dollar capital spent (much of which will be diverted from other priorities), and the political capital spent.

For example, in the case of Iraq, I have never felt the Bush administration, in their zeal, never properly weighed the ultimate costs of that war. Their planning was spotty, at best, and what they did plan for was wildly optimistic. What bothered me most of all, however, is that no one seemed to incorporate any of the historical lessons we learned during previous wars — particularly post-conflict reconstruction/nation building.

Asking “was it worth it” in no was trivializes anything or gives anyone carte blanche, and to be frank, your assumption that it does is cynical nonsense.

Noah — Regarding reparations, again you try to make a simple issue complex.

If the Korean War was worth fighting in the first place, and the Inchon landing was the turning point of the war, and none of the generals planning that landing did anything outside of reasonable contemporary military necessity during the course of that landing, then there should be no reparations. Because the fact is, during ANY battle of ANY war, one could argue ANY act done that killed innocent people should require reparations. Which is absurd.

There were acts committed during the Korean War that could be classified as war crimes, but I don’t think the Inchon invasion was one of them. If you look at every amphibious landing from WW II and Korea, they were virtually always preceded by a naval bombardment and air attacks to soften up enemy defenses. So Inchon was wholly unremarkable in that regards. US and coalition commanders did not know how many North Koreans were dug in around the Inchon invasion route, so they preceded the landing with the standard precautionary measures.

Just in passing: I am a great admirer of Mr Leonard Rifas; over his entire career he has striven to make comics that made a difference in our lives.

Here’s to the return of ‘Corporate Crime Comics’ and of ‘Itchy Planet’, Mr Rifas — we can use them both!

And for the record, I’ll be attending the 60th anniversary commemoration of the signing of the Korean War cease-fire on July 27, 1953. At this event, centered around the Korean War Memorial in Washington, DC, representatives of the US and a grateful Republic of Korea will be honoring the living and dead Korean War veterans who made a free South Korea possible.

” none of the generals planning that landing did anything outside of reasonable contemporary military necessity during the course of that landing, then there should be no reparations.”

You’ve changed the ground there. Is it the case that any atrocities are fine as long as the goal is just? If so, then bombing a bunch of civilians looks a lot like an atrocity. If it was an accident and we’re sorry, then we should be sorry by paying reparations. If it wasn’t an accident, then obviously all the more reason.

It just seems to me that when you’re at the point where bombing large numbers of civilians is not considered an atrocity, then virtually nothing is an atrocity. It’s like saying, oh, well, waterboarding isn’t really torture. It’s an excuse, not a good faith argument.

I’ve always been uncertain what to think about the Korean War. But if you’re looking at the entire country leveled and massive civilian casualties…yeah, I think “was it worth it” seems like the answer really tilts towards “no”.

Again, we didn’t create a free South Korea; we won on behalf of an authoritarian state that later became democratic. There’s certainly reason to believe that the North Koreans would not be as batshit insane as they are now if not for the horrific results of the war. A unified Korea would probably be significantly worse than the south and a good bit better than the north — and there would have quite possibly been much less loss of life. I don’t really know how you look at that and say, yes, absolutely it was worth it…unless the lives of buckets and buckets of civilians don’t actually matter to you. Which is why the “is it worth it” calculus is often problematic. Worth it to whom?

Wait, Russ, are you actually saying that civilian casualties are a universal constant of conflict?

A brief wikipedia search reveals highly differential ratios of combatants to civilians killed across United States historical conflicts (with, incidentally, the Korean Campaign as a high mark.) So, we can safely say that innocents have died. But the sort of generalization that you’re doing, saying “They’re going to die, deal with it.” is bizarrely fatalist. What is the point of saying something like that? What is the goal? Is it to inure us to the losses? To densensitize us to them? To make us shrug our shoulders and grit our teeth and look past the casualty numbers? I don’t think that any of those things are particularly commendable.

Your enemy’s morality is always beside the point. How we conduct ourselves in combat, as a nation and as individuals, and the morality that we bring to the situation that we (collectively or individually) find ourselves in, is worthy of discussion and critique. Pointing fingers at them and saying “But look at how horrible they are/were!” is childish and despicable. I don’t care if we were fighting an army of death-and-chaos-worshipers. The things that they’ve done has nothing to do with how we conduct ourselves in regards to them, especially if those things are predictable. It’s not a fucking child’s argument; saying “he started it!” and “look what Timmy did!” has no place when we’re talking about something with the gravity of war. We aspire to be good, not “comparatively better” than monsters. The only place that talking about North Korean war crimes has is in despairing for and learning from their actions and helping along our own self-improvement (e.g. trying to see what we can do to avoid the sort of things we find disgusting); patting ourselves on the back for being better than the other guy is fucking pathetic.

Saying “Well what would you have done?” isn’t constructive; it’s simply a way to deflect self-criticism. The complexity of the situations and the contexts of the people making decisions in them are too wound up in history to make any sort of counter-factual hypothetical anything other than an empty story.

Yeah…to talk about something that I know more about…it seems like Russ’ argument here would basically excuse Hiroshima, or take it off the table as a topic of discussion. The Japanese certainly did horribly evil things; if there’s a just war, WW II would be it. Once you’ve answered the “was it worth it” question — which it seems like WW II was — you’re then into the “well, civilian casualties happen” argument, which essentially eliminates the distinction between civilian deaths and combatant deaths which is fairly basic to most efforts to think about morality in war.

Once you’ve gotten there, it’s a short jump to saying, well, lots of Americans would have died in an invasion of Japan, so killing children who aren’t fighting you just becomes one of those inevitable things.

In practice…it’s really deeply unclear that dropping the bombs was necessary or in any way vital to the war effort. They seem to have been dropped basically because the people in charge didn’t really care about dead Japanese people, regardless of whether or not Americans would have died (and there’s plenty of reason to think Japan would have surrendered without an invasion of the home islands.) I think that’s where Russ’ logic takes you; if the cause is moral, the deaths of the enemy, civilian or armed, have no moral weight.

I think that’s a pretty terrible place to end up myself. I think it is actually generally the logic of war…which is why war is almost never “worth it.” I doubt the Korean war was.

Leonard: That’s certainly interesting information re: Kurtzman’s enormous amount of research from uncensored sources. Because Toth’s art in itself isn’t particularly problematic – there’s so much about the technology of war which can look “beautiful.” It’s clearly the script and choice of subject matter which creates the modern day dissonance. “Thunderjet!” isn’t quite as grotesque as an early story like “Contact” but it is clearly not cut from the same cloth as “Corpse on the Imjin” (which is also quite “pleasing” to look at).

Anyway, based on your research, are the non-EC Korean war comics considerably worse than the Kurtzman ones (“worse” not in an aesthetic sense but as propaganda tools)? That’s what their reputation would have us believe.

Sorry I didn’t respond sooner — I was out of town.

Noah — Your arguments about South Korea’s eventual democratization are wrong, since, when it was originally formed, it WAS a democracy. That went away later, but the ROK has since returned to its democratic roots. So from Truman’s POV, he was saving a fledgling democracy.

I find it alarming that you also are apologizing for North Korea, making the specious argument that the reason they are “batshit crazy” is likely due to the fact that the country is divided.

That is wrong on so many levels. It’s also an argument that can be made about any despot or fascist state. Using your logic, one could argue that things would have been swell if we’d just have played ball with Imperial Japan, or Nazi Germany.

And that’s where we have to circle around and ask if a war — any war — is worth it? If World War II had never happened, the loss of military and civilian lives would invariably much, much less, but we’d have had two powerful, fascist superpowers to contend with.

Ditto for the American Civil War. Was it worth the death and destruction to end slavery in the US?

You tell me. You’ve avoided this very basic question like the plague — no doubt because it makes you uncomfortable pondering that the price of war, in human terms, is never clear-cut and philosophically easy. For anyone who decides to enter their country into a war, they are issuing a death sentence on a portion of their military and civilian population — all in the hopes the end result is what they were hoping for.

No one wins a war at no cost — regardless of how admirable the rationale

Owen wrote: “But the sort of generalization that you’re doing, saying “They’re going to die, deal with it.” is bizarrely fatalist.”

No, it is brutally honest. We invaded Iraq with incredibly naïve expectations at the highest levels of government. If I’d have been sitting at the pre-war planning table with President Bush, I’d have spelled it out just as bluntly. It is imperative each and every time that everyone understands going in exactly what is at stake. And after laying out the realistic costs in blood, money, priorities and political capital, I would have closed with the same question I asked Noah: “Is it worth it?”

You also wrote: “Your enemy’s morality is always beside the point. How we conduct ourselves in combat, as a nation and as individuals, and the morality that we bring to the situation that we (collectively or individually) find ourselves in, is worthy of discussion and critique. Pointing fingers at them and saying “But look at how horrible they are/were!” is childish and despicable.”

Bullshit.

The enemy’s behavior is a crucial part of the cost equation and must be addressed when contemplating any potential conflict.

I agree that during a conflict, civilian leadership should expect their commanders and troops to adhere to accepted contemporary norms for combat. However, Korea was a very difficult war — especially during the first year. The US and coalition forces were nearly wiped out during the North’s initial Blitzkrieg, making for desperate times. When the Chinese entered the war in late 1950, using human wave tactics US forces hadn’t seen since the Pacific island-hopping campaign in the latter part of WW II, the desperation reached exponential levels. That desperation prompted the massive bombing campaign the US and its allies employed.